Avalon Hollywood

The building in 2007 | |

| |

| Former names | The Hollywood Playhouse, The WPA Federal Theater, El Capitan Theatre, The Jerry Lewis Theatre, The Hollywood Palace, The Palace |

|---|---|

| Address | 1735 N. Vine Street |

| Location | Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°06′10″N 118°19′37″W / 34.1027°N 118.3270°W |

| Owner | Hollywood Entertainment Partners |

| Type | Concert hall, nightclub, afterhours, lounge, restaurant, bar |

| Genre(s) | Big band, rock and roll, pop, electronic dance |

| Seating type | Standing room only, dance floor |

| Capacity | 1,250 |

| Construction | |

| Opened | January 24, 1927 |

| Renovated | 2007–2008 |

| Website | |

| avalonhollywood | |

| Designated | April 4, 1985[1] |

| Part of | Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment National Historic District |

| Reference no. | 85000704 |

Avalon (or Avalon Hollywood) is a historic nightclub in Hollywood, California, located near the intersection of Hollywood and Vine, at 1735 N. Vine Street. It has previously been known as The Hollywood Playhouse, The WPA Federal Theatre, El Capitan Theatre, The Jerry Lewis Theatre, The Hollywood Palace and The Palace. It has a capacity of 1,500, and is located across the street from the Capitol Records Building.

History

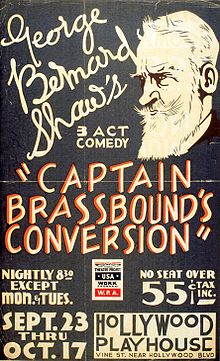

[edit]The Hollywood Playhouse

[edit]Originally known as The Hollywood Playhouse, the theater at 1735 N. Vine opened for the first time on January 24, 1927.[2] It was designed in the Spanish Baroque style by the architectural team of Henry L. Gogerty (1894–1990) and Carl Jules Weyl (1890–1948) in 1926–1927.[3] There was an unrelated, later theater Hollywood Playhouse at 1445 North Las Palmas Avenue.[4][5]

Federal Theatre Project

[edit]

During the Great Depression, the Hollywood Theatre operated under the Federal Theatre Project of the Works Progress Administration, and was a venue for government-sponsored theatrical events.[2]

The El Capitan Theatre

[edit]In the 1940s, the theatre was renamed The El Capitan Theatre and was used for a long-running live burlesque variety show called Ken Murray's Blackouts.[6]

In the 1940s, Bob Hope's NBC radio show originated from the El Capitan.

In the 1950s, the theatre was converted by NBC into a television studio. It was from a set on this stage that Richard Nixon delivered his famous "Checkers speech" on September 23, 1952.[7] This event is often mistakenly said to have taken place at the El Capitan Theatre on nearby Hollywood Boulevard, though that theater was never a television studio and in 1952 was operating as a movie house called Paramount Theatre.[8] Also in 1952, the first nationally televised telethon, in support of the United States Olympic Team and featuring Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Frank Sinatra, was held here.[9]

The theatre was home to the NBC shows The Colgate Comedy Hour, Truth or Consequences and This Is Your Life.[6] Upon completion of the NBC "Color City" studios in Burbank, NBC vacated the theater and ABC moved in, with The Lawrence Welk Show,originating from the El Capitan.

The Jerry Lewis Theatre

[edit]In 1963 American Broadcasting Company (ABC) television renovated the building, spending $400,000. Jerry Lewis used the theater/radio studio for his weekly Saturday night television program (lasting 13 weeks from September to December 1963)[1], and appropriately renamed the theater The Jerry Lewis Theatre. The stage had an existing rope counterweight fly system. The backstage second floor fly weights are located stage right. Located stage left are the double-load in doors that the stage alley connected and leads to and from Vine Street. All stage scenery was moved in and out of the stage load-in entrance.

Opposite this stage load-in door was the "star dressing room" which was completely rebuilt for Jerry Lewis. The first floor dressing room had a small front bar with a mirrored back bar, an upright piano, and a sofa lounge area. A circular spiral metal stairway led to the second floor, a make-up mirrored counter desk, with a Hollywood bed/couch. The adjacent toilet suite was equipped with a wall mounted telephone for Lewis to conduct business while using the facilities and his make-up area. The front stage apron in front of the proscenium was extended by filling (pouring concrete into) the original orchestra pit. A stage-centered 4' wide concrete camera ramp connected the stage apron with a 6' deep camera aisle against the auditorium back wall. The "level" concrete ramp and stage apron supported the Chapman Crane required for video taping talent and performers.

The TV control booth was situated on the left rear auditorium side facing the stage (which would be camera left). Behind the control booth was the video tape room where Ampex video tape machines were located. A Vine Street access door provided entry and load-in for equipment. In the auditoriums' right side (camera right) the concrete level floor, connecting the apron, was filled in to the back auditorium wall. This became the orchestra/band area. William "Bill" Morris III was the show's art director. He positioned a host platform on the left side stage, which had hydraulic lifts, during the course of Lewis conducting interviews with guests, the "home base" desk seating area could be raised 8 feet above the stage floor.

The balcony audience could view the host and talent and the Chapman Crane Camera could be at eye level with talent. Stage center was reserved as a performance area. New audience seating was located either side of the center camera aisle. The electricians control area was balcony located. ABC completely rewired for all electrical and video and sound equipment and soundproof booths. Offices on the Vine Street front second floor were renovated for the production/Producer's office complex. A staircase entrance located on the front left outdoor lobby led to the second floor offices.

The box office, on the right of the outdoor lobby, open daily for the ABC page staff to distribute audience tickets for The Jerry Lewis Show and all of ABC's Talmadge Lot TV shows, including the Lawrence Welk show and game shows, The entire building's exterior and interior were freshly finished and painted, new carpets in the main lobby, center staircase up to the cleaned up balcony floor, refurbished balcony seating.

The Hollywood Palace

[edit]Following the cancelation of the Lewis show, ABC renamed the building The Hollywood Palace. Launched in January 1964, The Hollywood Palace was a one-hour weekly variety series with a rotating roster of headliner guest hosts. Bing Crosby served as m.c. in the debut show, the series finale and more than thirty episodes in between. Other hosts included Liberace, Jimmy Durante, Ginger Rogers, Victor Borge, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Cyd Charisse and Tony Martin, Van Johnson, Betty Hutton, Diana Ross & The Supremes, Judy Garland, Alice Faye & Phil Harris, Groucho Marx and Louis Armstrong [2]. The program was a huge success and continued for more than seven years (194 episodes), concluding on February 4, 1970.

ABC continued to use the studio-building, taping replacement programming-series, and other TV broadcast programs. (ABC relocated the Lawrence Welk Syndicated Show from their ABC-lot stage E back to the Palace in the mid 1970s, until the Welk Group moved the show to CBS Television City for two of its latter seasons.) The Hollywood Palace television series was an ABC-TV West Coast production inaugurated by the network to compete with the Sunday-night CBS-TV Ed Sullivan show. ABC approached Nick Vanoff and Bill Harbach, open for their suggesting a prestige variety hour format. In response to the network, Vanoff and Harbach asked Bing Crosby to be primary host for a variety-vaudeville format program, and to break up his hosting assignments with notable Hollywood movie celebrities alternating host assignments. With Vanoff/Harbach's New York based production affiliation with the Perry Como TV series, the network bought the variety concept as a high-end mid-season replacement.

Since ABC had cancelled The Jerry Lewis Show, the studio facility had been completely renovated. The Network needed something to fulfill their long-term lease for the stage-studio space. ABC-TV never wanted to be burdened with property, preferring to rent a facility. Zodiac Productions established by Vanoff and Harbach brought together their same staff that they had put together four months previously taping a Bing Crosby Color Special (Aug 1963) for CBS-TV at NBC-Burbank. Jim Trittipo, as art director, Hub Braden, as his assistant art director, Rita Scott, as associate producer, Jerry McPhie as production manager, Les Brown and his musicians as musical direction team, including a writing team and talent management team. Trittipo established the opening format for the show by designing an opening "look" setting, which, after the Host introduction and musical segment opened the program, the original set would transform—on camera—into a new stage setting for the next performer and act!

By not going into a commercial break, sometimes the second act and setting would transform into a third act altered stage set transformation. This became the novelty for the variety hour. And made the audience stick with the tube by not switching channels during the normal network scheduled commercial break. Because the producers had Las Vegas and Reno showroom acts available to import for the variety acts, the producers were able to fly these performers into LA-Burbank for the show. The adjacent parking lot became an extra bonus for the show to book in high-flying wire walking and aerialist & trapeze performers, as well as animal acts which required large set-up space.

These types of acts were not possible on Ed Sullivan's CBS show. Frank Sinatra's lone visit as host paired him with jazz legend Count Basie. Sammy Davis Jr. was a frequent guest performer and Dean Martin's two hosting assignments in 1964 led to his own NBC-TV variety series. Vanoff and Harbach allowed Martin to come to the studio on tape day with very little, if any, rehearsal. Never rehearsing musical segments, he sang numbers cold while the band played keep-up! Rowan and Martin, ditto! The Palace was a springboard for many personalities getting a series shot. Fred Astaire hosted four shows which opened negotiations with NBC-TV for their own Fred Astaire Emmy-winning special. The program revived many show business careers.

ABC converted the Hollywood Palace from a black-and-white TV studio to the network's first West-Coast color broadcast facility during the 1965 summer hiatus. On September 18, 1965, The Hollywood Palace began to be broadcast in full color. The Lawrence Welk Show moved from the ABC-Talmadge lot alternating their taping schedule with the Hollywood Palace. ABC installed four RCA TK-41 color cameras and renovated the Welk stage to color during this period. The Welk show moved back to the ABC lot after their 1966–67 season of shows. Vanoff and Harbach produced the King Sisters Variety Show as a pilot in August 1967. This pilot sold and was slotted into the studio taping each week in front of the Palace's end week schedule. The studio facility was in full use.

The Merv Griffin Show was recorded at the Hollywood Palace on 27 March 1975, to be broadcast on 14 April 1975. The guests were: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Transcendental Meditation), Ellen Corby (The Waltons), Harold H. Bloomfield and California State Senator Arlen F. Gregorio.

The Palace

[edit]In 1978, ABC sold the theatre to private businessman Dennis Lidtke, who restored it and reopened it four years later with an abridged name, The Palace. The theater's audience seating area was removed. The audience raked floor was leveled to flush (same level) out from the lobby entrance area to the stage apron. Bands were located on the stage area. A double staircase was installed against the auditoriums back wall with an open arch which connected to the lobby staircase first landing, for balcony access, where tables and seating were arranged for balcony viewing of the band and dance floor below. One early production using the revamped facility was the 1983 Sheena Easton HBO concert special, Sheena Easton Live at the Palace, Hollywood. It was the venue for the performance portion of Bruce Willis' ACE nominated HBO special "The Return of Bruno", which was directed by Jim Yukich. It was written and produced by Bruce Willis, Paul Flattery and Jim Yukich, and co-written by Bruce DiMattia.

Avalon (as The Palace) is featured prominently in the film Against All Odds.

The punk band Ramones played their 2263rd and final show here on August 6, 1996. It was recorded for billboard live for the album We're Outta Here!. The building has hosted the American Music Awards.[10]

Avalon

[edit]1735 Vine was purchased by Hollywood Entertainment Partners in September 2002, and renamed Avalon. Since 2004, the venue has been open to the public for "Avaland".[11][12] "Control" is focused around dubstep, Trap and Electro, with a scene described as "indie dance".[13] Seeing that clubgoers were more into electronic bands and live or semi-live acts, co-owner Steve Adelman explained that he aimed for "a whole production and visual experience that's not just focused on watching a guy on two turntables."[14] "Avaland", by contrast, brings in the bigger-name DJs, mainly playing house music, trance and techno music. Avalon also included a VIP restaurant section called the Spider Club.[15] Adelman said his aim for the Hollywood Spider Club was to offer "the intimate experience of nightlife people enjoyed in the golden age of Hollywood."[16] Spider Club was transformed into Bardot in 2008 and remains the preeminent venue in Los Angeles to see up and coming acts as well as established ones wanting to play an intimate venue.

In the mid-2000s Avalon Hollywood also hosted many one-time events, including a political fundraiser where the Black Eyed Peas performed, an anniversary party for Us Weekly, and a birthday party for Bruce Willis.[17]

Many top EDM artists and deejays have played at Avalon's "Avaland" nights since it opened, including Tiesto,[18] Marcus Schulz,[19] Sasha,[20] Digweed[21] and Paul Oakenfold.[22]

The owner, John Lyons used to own and operate the original Avalon located in Boston, Massachusetts at 15 Lansdowne Street in a historic building of its own, right behind Fenway Park. The original Avalon and its sister club Axis were closed and demolished in 2007 to make way for The House of Blues.[23] Avalon Hollywood's success led Adelman to expand in the area by opening Club 86 in October 2007 in the old Hillview Apartment building at Hudson Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard, where Rudolph Valentino is said to have once had a speakeasy.[24] And, expanding into Asia, 2011 Adelman opened Avalon at the Marina Bay Sands Casino in Singapore.[25][26] It was Singapore's largest club at the time.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District". United States Department of the Interior – National Park Service. April 4, 1985.

- ^ a b "Avalon Hollywood: History". Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ Pacific Coast Architecture Database: Palace Theater

- ^ "Hollywood Playhouse, 1445 N. Las Palmas Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90028". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles Free Press : Film". ad sausage. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

Los Angeles Free Press

- ^ a b "Hollywood Entertainment District". Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ Alan Michelson (2011). Hollywood Playhouse Theatre, Hollywood, Los Angeles, CA. University of Washington Pacific Coast Architecture Database.

- ^ Bobby Ellerbee (July 9, 2014). "The ODD History Of The TWO El Capitan Theaters in Hollywood…". eyesofageneration.com.

- ^ Jaak Treiman (2011). A Diplomatic Guide to Los Angeles: Discovering Its Sites and Character. Velak Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-9835158-0-7.

- ^ "RA: Resident Advisor - Avalon Hollywood - California Nightclub". Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ "Avalon". Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ "Avalon". Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Scott T. Sterling (June 5, 2009). "Stepping into indie dance era". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Dennis Romero (April 1, 2009). "THE LAST DANCE: IS THE SUPERSTAR-DJ ERA OVER?". LA Weekly. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Kuh, Patric (July 2004). "Spider Bite". Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ Katie Ann Echeverria Rosen. "Spiderman may be the movie to see this summer but Spider Club is the place to be seen". Splash Magazines. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ "Inside Hollywood's Party Scene". Discover Hollywood, Summer 2005. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ "Review: Tiesto: In Search of Sunrise". Resident Advisor. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "AVALON presents NYE2020 | Markus Schulz [Open to Close] | AVALON Hollywood". avalonhollywood.com. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Mixes, Global Sets Dj. "Sasha – Live at Avalon, Hollywood – 26-APR-2014". Global-Sets.com. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "John Digweed". Resident Advisor. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Avalon presents Paul Oakenfold | Avalon Hollywood". avalonhollywood.com. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "A Look at Boston's Music Venues Through the Years". mmmmaven.com. August 29, 2016. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Margaret Wappler (September 20, 2007). "Legends from L.A. night life". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- ^ Olivia Vanni (August 12, 2011). "We Hear: John Lyons, Traci Bingham, James Montgomery and more". Boston Herald. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ David Pierson (July 23, 2011). "Uptight Singapore now global mecca for gamblers". The Seattle Times. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ^ "Avalon". SG Magazine. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help)

External links

[edit]- Culture of Los Angeles

- Culture of Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Landmarks in Los Angeles

- Theatres in Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Works Progress Administration in California

- Event venues established in 1927

- Buildings and structures in Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Buildings and structures in Los Angeles

- 1920s architecture in the United States

- Historic district contributing properties in California

- Theatres on the National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles