Parker Solar Probe

Parker Solar Probe artist rendering | |||||||||||||||

| Names | Solar Probe (before 2002) Solar Probe Plus (2010–17) Parker Solar Probe (since 2017) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Heliophysics | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | NASA · Applied Physics Laboratory | ||||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2018-065A | ||||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 43592 | ||||||||||||||

| Website | solarprobe | ||||||||||||||

| Mission duration | Planned: 6 years, 321 days | ||||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | Applied Physics Laboratory | ||||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 685 kg (1,510 lb)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Dry mass | 555 kg (1,224 lb) | ||||||||||||||

| Payload mass | 50 kg (110 lb) | ||||||||||||||

| Dimensions | 1.0 m × 3.0 m × 2.3 m (3.3 ft × 9.8 ft × 7.5 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Power | 343 W (at closest approach) | ||||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||||

| Launch date | Planned August 12 07:31 UTC, 2018[2][3] | ||||||||||||||

| Rocket | Delta IV Heavy / Star-48BV[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-37 | ||||||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||||||

| Reference system | Heliocentric | ||||||||||||||

| Perihelion altitude | 0.040 AU (6.0 million km; 3.7 million mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Aphelion altitude | 0.730 AU (109.3 million km; 67.9 million mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Inclination | 3.4° | ||||||||||||||

| Period | 88 days | ||||||||||||||

| Transponders | |||||||||||||||

| Band | Ka band X band | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Official insignia for the Parker Solar Probe mission | |||||||||||||||

Parker Solar Probe (previously Solar Probe, Solar Probe Plus, or Solar Probe+, abbreviated PSP[6]) is a planned NASA robotic spacecraft to probe the outer corona of the Sun.[3][7][8] It will approach to within 8.86 solar radii (6.2 million kilometers or 3.85 million miles) from the "surface" (photosphere) of the Sun[9] and will travel, at closest approach, as much as 700,000 km/h (430,000 mph).[10]

The project was announced in the fiscal 2009 budget year. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory designed and built the spacecraft, which was originally scheduled to launch in 2015.[11] The launch date was then rescheduled to the summer of 2018.[2] This was the first time a NASA spacecraft was named after a living person, honoring physicist Eugene Parker.[12]

A memory card containing the names of over 1.1 million people was mounted on a plaque and installed below spacecraft’s high-gain antenna on May 18, 2018.[13] The card also contained photos of Parker, professor emeritus at the University of Chicago, and a copy of his 1958 scientific paper.

History

The Parker Solar Probe concept originates from a predecessor Solar Orbiter project conceived in the 1990s. Similar in design and objectives, the Solar Probe mission served as one of the centerpieces of the eponymous Outer Planet/Solar Probe (OPSP) program formulated by NASA. The first three missions of the program were planned to be the Solar Orbiter, the Pluto and Kuiper belt reconnaissance mission Pluto Kuiper Express, and the Europa Orbiter astrobiology mission focused on Europa.[14][15] Following the appointment of Sean O'Keefe as Administrator of NASA, the entirety of the OPSP program was cancelled as part of President George W. Bush's request for the 2003 United States federal budget.[16] Administrator O'Keefe cited a need for a restructuring of NASA and its projects, falling in line with the Bush Administration's wish for NASA to refocus on "research and development, and addressing management shortcomings."[16]

The cancellation of the program also resulted in the initial cancellation of New Horizons, the mission that eventually won the competition to replace Pluto Kuiper Express in the former OPSP program.[17] That mission, which would eventually be launched as the first mission of the New Frontiers program, a conceptual successor to the OPSP program, would undergo a lengthy political battle to secure funding for its launch, which occurred in 2006.[18] Plans for the Solar Probe mission would later manifest as the Solar Probe Plus in the early 2010s.[19]

In May 2017, the spacecraft was renamed Parker Solar Probe in honor of astrophysicist Eugene Parker.[20]

Overview

The Parker Solar Probe will be the first spacecraft to fly into the low solar corona. It will determine the structure and dynamics of the Sun's coronal magnetic field, understand how the solar corona and wind are heated and accelerated, and determine what processes accelerate energetic particles. The Parker Solar Probe mission design uses repeated gravity assists at Venus to incrementally decrease its orbital perihelion to achieve multiple passes of the Sun at approximately 8.5 solar radii, or about 6 million km (3.7 million mi; 0.040 AU).[21]

The spacecraft's systems are designed to endure the extreme radiation and heat near the Sun, where the incident solar intensity is approximately 520 times the intensity at Earth orbit, by the use of a solar shadow-shield. The solar shield is 11.4 cm (4.5 in) thick and is made of reinforced carbon–carbon composite, which is designed to withstand temperatures outside the spacecraft of about 1,377 °C (2,511 °F).[22] The shield is hexagonal and is mounted at the Sun-facing side of the spacecraft. The spacecraft systems and scientific instruments are located in the central portion of the shield's shadow, where direct radiation from the Sun is fully blocked. If the shield is not between the spacecraft and the sun, the probe will become damaged and inoperative within tens of seconds. As radio communication with Earth will take about eight minutes, the Parker Solar Probe will have to act autonomously and rapidly to protect itself. According to project scientist Nicky Fox, the team describe it as "the most autonomous spacecraft that has ever flown".[6]

The primary power for the mission is a dual system of solar panels (photovoltaic array). A primary photovoltaic array, used for the portion of the mission outside 0.25 AU, is retracted behind the shadow shield during the close approach to the Sun, and a much smaller secondary array powers the spacecraft through closest approach. This secondary array uses pumped-fluid cooling to maintain operating temperature.[23]

Trajectory

Parker Solar Probe · Sun · Mercury · Venus · Earth

The spacecraft trajectory will include seven Venus flybys over nearly seven years to gradually shrink its elliptical orbit around the Sun, for a total of 24 orbits.[1] The science phase will take place during those 7 years, focusing on the periods when the spacecraft is closest to the Sun. The near Sun radiation environment is predicted to cause spacecraft charging effects, radiation damage in materials and electronics, and communication interruptions, so the orbit will be highly elliptical with short times spent near the Sun.[25]

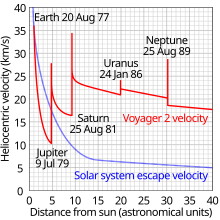

The trajectory requires high launch energy, so the probe will be launched on a Delta IV Heavy class launch vehicle and an upper stage based on the STAR 48BV solid rocket motor.[25] Interplanetary gravity assists will provide further deceleration relative to its heliocentric orbit, which may result in a heliocentric speed record at perihelion.[4][26] As the probe passes around the Sun, it will achieve a velocity of up to 200 km/s (120 mi/s), which will temporarily make it the fastest manmade object, almost three times as fast as the current record holder, Helios-B.[27][28][29] Like every object in an orbit, due to gravity the spacecraft will accelerate as it nears perihelion, then slow down again afterwards until it reaches its aphelion.

Scientific goals

The goals of the mission are: [25]

- Trace the flow of energy that heats the corona and accelerates the solar wind.

- Determine the structure and dynamics of the magnetic fields at the sources of solar wind.

- Determine what mechanisms accelerate and transport energetic particles.

Investigations

In order to achieve these goals, the mission will perform five major experiments or investigations: [25]

- Electromagnetic Fields Investigation (FIELDS) — This investigation will make direct measurements of electric and magnetic fields, radio waves, Poynting flux, absolute plasma density, and electron temperature. Its main instrument is a flux-gate magnetometer. The Principal investigator is Stuart Bale, at the University of California, Berkeley.

- Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun (ISIS)— This investigation will measure energetic electrons, protons and heavy ions. The instrument suite is composed of two independent instruments, EPI-Hi and EPI-Lo. The Principal investigator is David McComas, at the Princeton University.

- Wide-field Imager for Solar PRobe (WISPR)— These optical telescopes will acquire images of the corona and inner heliosphere. The Principal Investigator is Russell Howard, at the Naval Research Laboratory.

- Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP)— This investigation will count the electrons, protons and helium ions, and measure their properties such as velocity, density, and temperature. Its main instruments are two electrostatic analyzers and a Faraday cup. The Principal Investigator is Justin Kasper at the University of Michigan and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

- Heliospheric origins with Solar Probe Plus (HeliOSPP) is a theory and modeling investigation to maximize the scientific return from the mission. The Principal Investigator is Marco Velli at UCLA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

Planned timeline

Perihelion means the point in the PSP's orbit closest to the Sun

| Year | Events | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |||

| 2018 | NET Aug 12 Postponed launch[30] |

Nov 1 Perihelion #1 |

||||||||||||

| Sep 28 First flyby of Venus (period 150 days) |

||||||||||||||

| 2019 | Mar 31 Perihelion #2 |

Aug 28 Perihelion #3 |

Dec 21 Second flyby of Venus (period 130 days) | |||||||||||

| 2020 | Jan 24 Perihelion #4 |

Jun 2 Perihelion #5 |

Sep 22 Perihelion #6 |

|||||||||||

| Jul 6 Third flyby of Venus (period 112.5 days) |

||||||||||||||

| 2021 | Jan 13 Perihelion #7 |

Apr 24 Perihelion #8 |

Aug 5 Perihelion #9 |

Nov 16 Perihelion #10 |

||||||||||

| Feb 16 Fourth flyby of Venus (period 102 days) |

Oct 11 Fifth flyby of Venus (period 96 days) |

|||||||||||||

| 2022 | Feb 21 Perihelion #11 |

May 28 Perihelion #12 |

Sep 1 Perihelion #13 |

Dec 6 Perihelion #14 |

||||||||||

| 2023 | Mar 13 Perihelion #15 |

Jun 17 Perihelion #16 |

Sep 23 Perihelion #17 |

Dec 24 Perihelion #18 |

||||||||||

| Aug 16 Sixth flyby of Venus (period 92 days) |

||||||||||||||

| 2024 | Mar 25 Perihelion #19 |

Jun 25 Perihelion #20 |

Sep 25 Perihelion #21 |

Dec 19 Perihelion #22 First close approach to the Sun | ||||||||||

| Nov 2 Seventh flyby of Venus (period 88 days) |

||||||||||||||

| 2025 | Mar 18 Perihelion #23 |

Jun 14 Perihelion #24 |

Sep 10 Perihelion #25 |

Dec 7 Perihelion #26 |

||||||||||

After the first Venus fly-by, the probe will be in an elliptical orbit with a period of 150 days (two-thirds the period of Venus), making three orbits while Venus makes two. On the second fly-by, the period shortens to 130 days. After less than two orbits (only 198 days later) it encounters Venus a third time at a point earlier in the orbit of Venus. This encounter shortens its period to half of that of Venus, or about 112.5 days. After two orbits it meets Venus a fourth time at about the same place, shortening its period to about 102 days. After 237 days it meets Venus for the fifth time and its period is shortened to about 96 days, three-sevenths that of Venus. It then makes seven orbits while Venus makes three. The sixth encounter, almost two years after the fifth, brings its period down to 92 days, two-fifths that of Venus. After five more orbits (two orbits of Venus) it meets Venus for the seventh and last time, decreasing its period to 88 or 89 days and allowing it to approach close to the Sun.[31]

Mission timeline

The original planned launch on 11 August, 2018 was missed after two delays resulted in the daily launch window expiring. The full window includes one opportunity per day from 11 August to 23 August 2018. The launch is currently planned for 12 August 2018.[32]

See also

- Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), launched 1997

- List of vehicle speed records

- MESSENGER, Mercury orbiter (2011-2015)

- Sun observation spacecraft

- Helios, a pair of spacecraft launched in the 1970s to approach the Sun inside the orbit of Mercury, 63 R☉

- Solar Orbiter, 45 R☉

- STEREO, launched 2006

- WIND, launched 1994

- Ulysses, solar polar orbiter (1990-2009)

- Spacecraft design

References

- ^ a b Parker Solar Probe - Extreme Engineering. NASA.

- ^ a b "Parker Solar Probe Ready for Launch on Mission to the Sun". NASA. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (August 11, 2018). "NASA Delays Parker Solar Probe Launch". The New York Times. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (March 18, 2015). "Delta 4-Heavy selected for launch of solar probe". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "Parker Solar Probe Science Gateway | Parker Solar Probe Science Gateway". sppgway.jhuapl.edu. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Clark, Stuart (July 22, 2018). "Parker Solar Probe: set the controls for the edge of the sun..." The Guardian.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (May 31, 2017). "Newly Named NASA Spacecraft Will Aim Straight for the Sun". New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Applied Physics Laboratory (November 19, 2008). "Feasible Mission Designs for Solar Probe Plus to Launch in 2015, 2016, 2017, or 2018" (PDF). Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original (.PDF) on April 18, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tony Phillips (June 10, 2010). "NASA Plans to Visit the Sun". NASA. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Garner, Rob (August 9, 2018). "Parker Solar Probe: Humanity's First Visit to a Star". NASA. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ M. Buckley (May 1, 2008). "NASA Calls on APL to Send a Probe to the Sun". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ "NASA Renames Solar Probe Mission to Honor Pioneering Physicist Eugene Parker". NASA. May 31, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ "NASA's Solar Parker Probe To Carry Over 1.1 Million Names To The Sun". Headlines Today. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ "Mcnamee Chosen to Head NASA's Outer Planets/Solar Probe Projects". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). April 15, 1998. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Maddock, R.W.; Clark, K.B.; Henry, C.A.; Hoffman, P.J. (March 7, 1999). "The Outer Planets/Solar Probe Project: "Between an ocean, a rock, and a hot place"". IEEE Xplore. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers · Institution of Engineering and Technology. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Berger, Brian (February 4, 2002). "NASA Kills Europa Orbiter; Revamps Planetary Exploration". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on February 10, 2002. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Savage, Donald (November 29, 2001). "NASA Selects Pluto-Kuiper Belt Mission Phase B Study". National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hand, Eric (June 25, 2015). "Feature: How Alan Stern's tenacity, drive, and command got a NASA spacecraft to Pluto". Science (journal). American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Fazekas, Andrew (September 10, 2010). "New NASA Probe to Dive-bomb the Sun". National Geographic. 21st Century Fox / National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Burgess, Matt. "Nasa's mission to Sun renamed after astrophysicist behind solar wind theory". Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ "Solar Probe Plus: A NASA Mission to Touch the Sun:". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. September 4, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Parker Solar Probe - Extreme Environments. NASA.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A.; et al. (2008). Solar Power System Design for the Solar Probe+ Mission (PDF). 6th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference. July 28-30, 2008. Cleveland, Ohio. AIAA 2008-5712.

- ^ Dave Doody (September 15, 2004). "Basics of Space Flight Section I. The Environment of Space". .jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d The Solar Probe Plus Mission: Humanity’s First Visit to Our Star. (PDF). N. J. Fox, M. C. Velli, S. D. Bale, R. Decker, A. Driesman, R. A. Howard, J. C. Kasper, J. Kinnison, M. Kusterer, D. Lario, M. K. Lockwood, D. J. McComas, N. E. Raouafi, A. Szabo. Space Science Reviews. December 2016, Volume 204, Issue 1–4, pp 7–48. doi:10.1007/s11214-015-0211-6

- ^ Scharf, Caleb A. "The Fastest Spacecraft Ever?". Scientific American Blog Network.

- ^ "Aircraft Speed Records". Aerospaceweb.org. November 13, 2014.

- ^ "Fastest spacecraft speed". guinnessworldrecords.com. July 26, 2015. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Parker Solar Probe - Check123, Video Encyclopedia, retrieved June 1, 2017

- ^ "Launch Schedule – Spaceflight Now". spaceflightnow.com. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ See data and figure at "Solar Probe Plus: The Mission". Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. 2017.

- ^ "Parker Solar Probe New Launch Date is Aug. 12". NASA. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

External links

- Parker Probe Plus at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

- Solar Probe Plus Mission Engineering Study Report

- NASA – Heliophysics Research

- Explorers and Heliophysics Projects Division (EHPD)

- NASA, Parker Solar Probe data & news