Ethosuximide

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Zarontin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682327 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (capsules, solution) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 93%[3] |

| Metabolism | liver (CYP3A4, CYP2E1) |

| Elimination half-life | 53 hours |

| Excretion | kidney (20%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.954 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H11NO2 |

| Molar mass | 141.170 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Melting point | 64 to 65 °C (147 to 149 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ethosuximide, sold under the brand name Zarontin among others, is a medication used to treat absence seizures.[4] It may be used by itself or with other antiseizure medications such as valproic acid.[4] Ethosuximide is taken by mouth.[4]

Ethosuximide is usually well tolerated.[5] Common side effects include loss of appetite, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and feeling tired.[4] Serious side effects include suicidal thoughts, low blood cell levels, and lupus erythematosus.[4][5] It is unclear if it has adverse effects on the fetus during pregnancy.[4] Ethosuximide is in the succinimide family of medications. Its mechanism of action is thought to be due to antagonism of the postsynaptic T-type voltage-gated calcium channel.[6]

Ethosuximide was approved for medical use in the United States in 1960.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] Ethosuximide is available as a generic medication.[4] As of 2019[update], its availability was limited in many countries, with concerns about price fixing in the United States.[9][10][11]

Medical uses

[edit]Ethosuximide is approved for absence seizures,[12] and is considered the first choice medication for treating them, in part because it lacks the idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity of the alternative anti-absence drug, valproic acid.[13]

Adverse effects

[edit]As with other anticonvulsants, ethosuximide carries a warning about use during pregnancy. Although a causal relationship with birth defects has not be established, the potential for harm to the baby is weighed against the known harm caused by a mother having even minor seizures.[4]

Central nervous system

[edit]Common

[edit]Rare

[edit]- paranoid psychosis

- increased libido

- exacerbation of depression

Gastrointestinal

[edit]- dyspepsia

- vomiting

- nausea

- cramps

- constipation

- diarrhea

- stomach pain

- loss of appetite

- weight loss

- gum enlargement

- swelling of tongue

- abnormal liver function

Genitourinary

[edit]- microscopic hematuria

- vaginal bleeding

Blood

[edit]The following can occur with or without bone marrow loss:

Skin

[edit]- urticaria

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome

- hirsutism

- pruritic erythematous rashes

Eyes

[edit]Drug interactions

[edit]Valproates can either decrease or increase the levels of ethosuximide; however, combinations of valproates and ethosuximide had a greater protective index than either drug alone.[14]

It may elevate serum phenytoin levels.

Mechanism of action

[edit]The mechanism by which ethosuximide affects neuronal excitability includes block of T-type calcium channels, and may include effects of the drug on other classes of ion channel. The primary finding that ethosuximide is a T-type calcium channel blocker gained widespread support, but initial attempts to replicate the finding were inconsistent. Subsequent experiments on recombinant T-type channels in cell lines demonstrated conclusively that ethosuximide blocks all T-type calcium channel isoforms.[citation needed] Significant T-type calcium channel density occurs in dendrites of neurons, and recordings from reduced preparations that strip away this dendritic source of T-type calcium channels may have contributed to reports of ethosuximide ineffectiveness.

In March 1989, Coulter, Huguenard and Prince showed that ethosuximide and dimethadione, both effective anti-absence agents, reduced low-threshold Ca2+ currents in T-type calcium channels in freshly removed thalamic neurons.[15] In June of that same year, they also found the mechanism of this reduction to be voltage-dependent, using acutely dissociated neurons of rats and guinea pigs; it was also noted that valproic acid, which is also used in absence seizures, did not do that.[16] The next year, they showed that anticonvulsant succinimides did this and that the pro-convulsant ones did not.[17] The first part was supported by Kostyuk et al. in 1992, who reported a substantial reduction in current in dorsal root ganglia at concentrations ranging from 7 μmol/L to 1 mmol/L.[18]

That same year, however, Herrington and Lingle found no such effect at concentrations of up to 2.5 mmol/L.[19] The year after, a study conducted on human neocortical cells removed during surgery for intractable epilepsy, the first to use human tissue, found that ethosuximide had no effect on Ca2+ currents at the concentrations typically needed for a therapeutic effect.[20]

In 1998, Slobodan M. Todorovic and Christopher J. Lingle of Washington University reported a 100% block of T-type current in dorsal root ganglia at 23.7 ± 0.5 mmol/L, far higher than Kostyuk reported.[21] That same year, Leresche et al. reported that ethosuximide had no effect on T-type currents, but did decrease noninactivating Na+ current by 60% and the Ca2+-activated K+ currents by 39.1 ± 6.4% in rat and cat thalamocortical cells. It was concluded that the decrease in Na+ current is responsible for the anti-absence properties.[22]

In the introduction of a paper published in 2001, Dr. Juan Carlos Gomora and colleagues at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville pointed out that past studies were often done in isolated neurons that had lost most of their T-type channels.[23] Using cloned α1G, α1H, and α1I T-type calcium channels, Gomora's team found that ethosuximide blocked the channels with an IC50 of 12 ± 2 mmol/L and that of N-desmethylmethsuximide (the active metabolite of mesuximide) is 1.95 ± 0.19 mmol/L for α1G, 1.82 ± 0.16 mmol/L for α1I, and 3.0 ± 0.3 mmol/L for α1H. It was suggested that the blockade of open channels is facilitated by ethosuximide's physically plugging the channels when current flows inward.

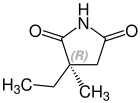

Stereochemistry

[edit]Ethosuximide is a chiral drug with a stereocenter. Therapeutically, the racemate, the 1: 1 mixture of ( S ) and ( R ) - isomers used.[24]

| Enantiomers of ethosuximide | |

|---|---|

CAS-Nummer: 39122-20-8 |

CAS-Nummer: 39122-19-5 |

Society and culture

[edit]Cost

[edit]As of 2019 there were concerns in the United States that the price of ethosuximide was inflated by manufacturers.[11][25]

Availability

[edit]Availability of ethosuximide is limited in many countries.[9] It was marketed under the trade names Emeside and Zarontin. However, both capsule preparations were discontinued from production, leaving only generic preparations available. Emeside capsules were discontinued by their manufacturer, Laboratories for Applied Biology, in 2005.[26] Similarly, Zarontin capsules were discontinued by Pfizer in 2007.[27] Syrup preparations of both brands remained available.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- ^ "List of nationally authorised medicinal products" (PDF). European Medicines Agency.

- ^ Patsalos PN (November 2005). "Properties of antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of idiopathic generalized epilepsies". Epilepsia. 46 Suppl 9 (s9): 140–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00326.x. PMID 16302888. S2CID 19462889.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Ethosuximide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 69, 74–75. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Huguenard, John R. (March 2002). "Block of T -Type Ca2+ Channels Is an Important Action of Succinimide Antiabsence Drugs". Epilepsy Currents. 2 (2): 49–52. doi:10.1046/j.1535-7597.2002.00019.x. PMC 320968. PMID 15309165.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b Hempel, Georg (2019). Methods of Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Including Pharmacogenetics. Elsevier. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-444-64067-3.

- ^ "Attorney General Tong leads 44-state coalition in antitrust lawsuit against Teva Pharmaceuticals, 19 other generic drug manufacturers, 15 individuals in conspiracy to fix prices and allocate markets for more than 100 different generic drugs" (Press release). Office of the Attorney General of the State of Connecticut. 12 May 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b "States sue generic drug makers, claiming a conspiracy to fix prices". consumeraffairs.com. 14 May 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Pharmaceutical Associates, Incorporated (2000). "Ethosuximide Approval Label" (PDF). Label and Approval History. Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Retrieved 2006-02-05.

- ^ Katzung, B., ed. (2003). "Drugs used in generalized seizures". Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (9th ed.). Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0071410929.

- ^ Bourgeois BF (December 1988). "Combination of valproate and ethosuximide: antiepileptic and neurotoxic interaction". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 247 (3): 1128–32. PMID 3144596.

- ^ Coulter DA, Huguenard JR, Prince DA (March 1989). "Specific petit mal anticonvulsants reduce calcium currents in thalamic neurons". Neuroscience Letters. 98 (1): 74–8. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(89)90376-5. PMID 2710401. S2CID 13413993.

- ^ Coulter DA, Huguenard JR, Prince DA (June 1989). "Characterization of ethosuximide reduction of low-threshold calcium current in thalamic neurons". Annals of Neurology. 25 (6): 582–93. doi:10.1002/ana.410250610. PMID 2545161. S2CID 20670160.

- ^ Coulter DA, Huguenard JR, Prince DA (August 1990). "Differential effects of petit mal anticonvulsants and convulsants on thalamic neurones: calcium current reduction". British Journal of Pharmacology. 100 (4): 800–6. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14095.x. PMC 1917607. PMID 2169941.

- ^ Kostyuk PG, Molokanova EA, Pronchuk NF, Savchenko AN, Verkhratsky AN (December 1992). "Different action of ethosuximide on low- and high-threshold calcium currents in rat sensory neurons". Neuroscience. 51 (4): 755–8. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(92)90515-4. PMID 1336826. S2CID 41451332.

- ^ Herrington J, Lingle CJ (July 1992). "Kinetic and pharmacological properties of low voltage-activated Ca2+ current in rat clonal (GH3) pituitary cells". Journal of Neurophysiology. 68 (1): 213–32. doi:10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.213. PMID 1325546.

- ^ Sayer RJ, Brown AM, Schwindt PC, Crill WE (May 1993). "Calcium currents in acutely isolated human neocortical neurons". Journal of Neurophysiology. 69 (5): 1596–606. doi:10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1596. PMID 8389832.

- ^ Todorovic SM, Lingle CJ (January 1998). "Pharmacological properties of T-type Ca2+ current in adult rat sensory neurons: effects of anticonvulsant and anesthetic agents". Journal of Neurophysiology. 79 (1): 240–52. doi:10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.240. PMID 9425195.

- ^ Leresche N, Parri HR, Erdemli G, Guyon A, Turner JP, Williams SR, et al. (July 1998). "On the action of the anti-absence drug ethosuximide in the rat and cat thalamus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 18 (13): 4842–53. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04842.1998. PMC 6792570. PMID 9634550.

- ^ Gomora JC, Daud AN, Weiergräber M, Perez-Reyes E (November 2001). "Block of cloned human T-type calcium channels by succinimide antiepileptic drugs". Molecular Pharmacology. 60 (5): 1121–32. doi:10.1124/mol.60.5.1121. PMID 11641441. S2CID 7098669.

- ^ Rote Liste Service GmbH (Hrsg.): Rote Liste 2017 – Arzneimittelverzeichnis für Deutschland (einschließlich EU-Zulassungen und bestimmter Medizinprodukte). Rote Liste Service GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, 2017, Aufl. 57, ISBN 978-3-946057-10-9, S. 182.

- ^ Staff, WMBF News. "South Carolina joins lawsuit against manufacturers in alleged conspiracy to fix prescription drug prices". wmbfnews.com. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Concern over ethosuximide capsule discontinuation". Pharm J. 275: 539. Oct 29, 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2008-08-31. (paywalled archive)

- ^ "Zarontin capsules discontinued". Archived from the original on 2012-06-26. Retrieved 2012-10-24.