RMS Laconia (1921)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2009) |

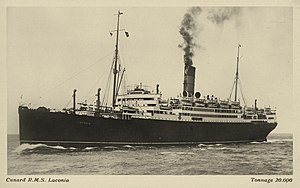

RMS Laconia

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Laconia |

| Owner | 1921–34: Cunard Line 1934–41: Cunard White Star Line |

| Operator | 1921–34: Cunard Line 1934–41: Cunard White Star Line |

| Port of registry | Liverpool |

| Route | Liverpool – Boston – New York |

| Builder | Swan Hunter, Wallsend, England |

| Launched | 9 April 1921 |

| Completed | January 1922 |

| Maiden voyage | 25 May 1922 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sunk by torpedo 12 September 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 601 ft 3 in (183.26 m) |

| Beam | 73 ft 7 in (22.43 m) |

| Draught | 32 ft 8 in (9.96 m) |

| Depth | 40 ft 6 in (12.34 m) |

| Installed power | 6 steam turbines, double reduction geared |

| Propulsion | Twin propellers |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h) |

| Capacity |

|

| Notes | 10,920,060 cubic feet (309,222 m3) refrigerated cargo space. |

The second RMS Laconia was a Cunard ocean liner, built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson as a successor of the 1911-1917 Laconia. The new ship was launched on 9 April 1921, and made her maiden voyage on 25 May 1922 from Southampton to New York City. At the outbreak of World War II she was converted into an Armed Merchant Cruiser, and subsequently a troopship. Like her predecessor, sunk during the First World War, this Laconia was also destroyed by a German submarine. Some estimates of the death toll have suggested that over 1,649 people were killed when the Laconia sank. The U-boat commander Werner Hartenstein then staged a dramatic effort to rescue the passengers and the crew of Laconia, which involved additional German U-boats and became known as the Laconia incident.

Description

Laconia was 601 feet 3 inches (183.26 m) long, with a beam of 73 feet 7 inches (22.43 m). She had a depth of 40 feet 6 inches (12.34 m) and a draught of 32 feet 8 inches (9.96 m). She was powered by six steam turbines of 2,561 nhp, which drove twin screw propellors via double reduction gearing. The turbines were made by the Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Company, Newcastle upon Tyne.[1] In addition to her passenger accommodation, Laconia had 54,089 cubic feet (1,531.6 m3) of refrigerated cargo space.[2]

Early career

Laconia was built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd, Wallsend, Northumberland.[1] Launched on 9 April 1921, she was completed in January 1922.[3] Her port of registry was Liverpool. The code letters KLWT and United Kingdom Official Number 145925 were allocated.[1] As a Royal Mail Ship, Laconia was entitled to display the Royal Mail "crown" logo as a part of its crest. In January 1923 Laconia began the first around-the-world cruise, which lasted 130 days and called at 22 ports.

On 8 September 1925, Laconia collided with the British schooner Lucia P. Dow in the Atlantic Ocean 60 nautical miles (110 km) east of Nantucket, Massachusetts, United States. Laconia towed the schooner for 120 nautical miles (220 km) before handing the tow over to the American tug Resolute.[4] In 1934, her code letters were changed to GJCD.[5] On 24 September 1934 Laconia was involved in a collision off the US coast, while travelling from Boston to New York in dense fog. It rammed into the port side of Pan Royal, a US freighter.[6] Both ships suffered serious damage but were able to proceed under their own steam. Laconia returned to New York for repairs, and resumed cruising in 1935.

Drafted into war service

On 4 September 1939, Laconia was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted into an armed merchant cruiser. By January 1940 she had been fitted with eight six-inch guns and two three-inch high-angle guns. After trials off the Isle of Wight, she embarked gold bullion and sailed for Portland, Maine and Halifax, Nova Scotia on 23 January. She spent the next few months escorting convoys to Bermuda and to points in the mid-Atlantic, where they would join up with other convoys.

On 9 June, she ran aground in the Bedford Basin at Halifax, suffering considerable damage, and repairs were not completed till the end of July. In October her passenger accommodation was dismantled and some areas filled with oil drums to provide extra buoyancy so that she would stay afloat longer if torpedoed.

During the period June–August 1941 Laconia returned to St John, New Brunswick and was refitted, then returned to Liverpool to be used as a troop transport for the rest of the war. On 12 September 1941, she arrived at Bidston Dock, Birkenhead and was taken over by Cammell Laird and Company to be converted. By early 1942 the work was complete, and for the next six months she made trooping voyages to the Middle East. On one such voyage the ship was used to carry prisoners of war, mainly Italian. She travelled to Cape Town and then set a course for Freetown, following a zigzag course and undertaking evasive steering during the night.

Final moments

On 12 September 1942, at 8:10 pm, 130 miles (210 km) north-northeast of Ascension Island, Laconia was hit on the starboard side by a torpedo fired by U-boat U-156. There was an explosion in the hold and many of the Italian prisoners aboard were killed instantly. The vessel immediately took a list to starboard and settled heavily by the stern. Captain Rudolph Sharp, who had also commanded another famous Cunard liner, RMS Lancastria when she was sunk by enemy action, was gaining control over the situation when a second torpedo hit Number Two hold. At the time of the attack, the Laconia was carrying 268 British soldiers, 160 Polish soldiers (who were on guard), 80 civilians, and 1,800 Italian prisoners of war.[7]

Captain Sharp ordered the ship abandoned and the women, children and injured taken into the lifeboats first. By this time, the ship's stern deck was awash. Some of the 32 lifeboats had been destroyed by the explosions and some surviving Italian prisoners tried to rush the lowering of the ones that remained. The efforts of the Polish guards were instrumental in controlling the chaotic situation on board and saved many lives.[citation needed] According to Italian survivors, many of the POWs were left locked in the holds, and those who escaped and tried to board lifeboats and liferafts were shot or bayoneted by British and Polish soldiers.[8]

At 9:11 pm Laconia sank, stern first, her bow rising to be vertical, with Sharp himself and many of the Italian prisoners still on board. The prospects for those who escaped the ship were only slightly better; sharks were common in the area and the lifeboats were adrift in the mid-Atlantic with little hope of rescue.

However, before Laconia went down, U-156 surfaced. The U-boat's efforts to rescue survivors of its own attack began what came to be known as the Laconia incident.

When Kapitänleutnant Werner Hartenstein, commanding officer of U-156, realized civilians and prisoners of war were on board, he surfaced to rescue survivors,[9] and asked BdU (the U-Boat Command in Germany) for help. Several U-Boats were dispatched; all flew Red Cross flags, and signalled by radio that a rescue operation was underway.

The next morning, a U.S. B-24 Liberator plane sighted the rescue efforts.[10] Hartenstein signaled the pilot for assistance, who then notified the American base on Ascension Island of the situation. The senior officer on duty there, Robert C. Richardson III, unaware [11] of the Germans' radio message, ordered that the U-boats be attacked. Despite the Red Cross flags, the survivors crowded on the submarines' decks and the towed lifeboats, the B-24 then started making attack runs on U-156. The Germans ordered their submarines to dive, abandoning many survivors. After the incident, Admiral Karl Dönitz issued the Laconia Order, henceforth ordering his commanders not to rescue survivors after attacks. Vichy French ships rescued 1,083 persons from the lifeboats and took aboard those picked up by the four submarines, and in all around 1,500 survived the sinking. Other sources state that only 1,104 survived and an estimated 1,649 persons died.

Amongst the French ships involved in the rescue were Annamite, Dumont-d'Urville and Gloire.[12]

Media

On 6 and 7 January 2011, BBC2 in the United Kingdom broadcast The Sinking of the Laconia, a two-part dramatisation of the sinking of Laconia.[13]

See also

- List by death toll of ships sunk by submarines

- Maritime disasters

- The Sinking of the Laconia

- List of ship launches in 1921

- List of shipwrecks in 1942

References

- ^ a b c "LLOYD'S REGISTER, STEAMERS AND MOTORSHIPS" (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ "LLOYD'S REGISTER, LIST DES NAVIRES POURVUS DE MACHINES FRIGORIFIQUES" (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Kludas, Arnold. "Great Passenger Ships of the World" Vol. II:1913–1923, p. 138. Cambridge, UK. Patrick Stephens, Ltd. 1976

- ^ "Casualty reports". The Times. No. 44062. London. 9 September 1925. col E, p. 20. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ "LLOYD'S REGISTER, NAVIRES A VAPEUR ET A MOTEURS" (PDF). Plimsoll Ship Data. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ "Steamers crash in fog off Cape". The New York Times. 25 September 1934. p. 45.

- ^ The Laconia Incident by Gudmundur Helgason

- ^ http://cronologia.leonardo.it/battaglie/batta108.htm

- ^ Alan Bleasdale drama sets the record straight on heroic U-boat captain The Observer, London Accessed 2 January 2011

- ^ Documentary about Atlantic War, @5:00

- ^ Bridgland, Tony. Waves of Hate: Naval Atrocities of the 2nd World War. p. 80 :"Nobody told us anything about Hartenstein’s message. We knew nothing of this until after the war (1963)"

- ^ [The Sinking of the Laconia: Survivors' Stories "he Loss of the Cunard Ship Laconia - Albert Goode MN"]. BBC. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "The sinking of the SS Laconia in World War II". BBC. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

Further reading

- Duffy, James P. The Sinking of the Laconia and the U-boat War: Disaster in the Mid-Atlantic (University of Nebraska Press, 2013) 129 pp.

External links

- 1921 ships

- Merchant ships of the United Kingdom

- RMS Laconia (1921)

- Ships built by Swan Hunter

- Ships of the Cunard Line

- Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II

- Tyne-built ships

- World War II merchant ships of the United Kingdom

- World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean

- Maritime incidents in September 1942