Rudaali

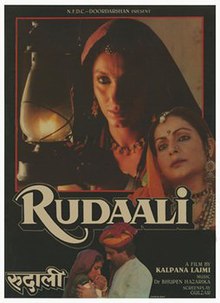

| Rudaali | |

|---|---|

Poster | |

| Directed by | Kalpana Lajmi |

| Written by | Gulzar |

| Based on | Rudaali by Mahasweta Devi |

| Produced by | Ravi Gupta Ravi Malik NFDC Doordarshan |

| Starring | Dimple Kapadia Raj Babbar Raakhee Amjad Khan |

| Cinematography | Santosh Sivan Dharam Gulati |

| Music by | Bhupen Hazarika |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Language | Hindi |

Rudaali (pronounced "roo-dah-lee"; transl. Female weeper)[a] is a 1993 Indian Hindi-language drama film directed by Kalpana Lajmi, written by Lajmi and Gulzar and based on a 1979 short story of the same name by Bengali author Mahasweta Devi. Set in a small village in Rajasthan, the film stars Dimple Kapadia as Shanichari, a lonely and hardened woman who, despite a lifetime of misfortune and abandonment, is unable to express grief through crying and is challenged with a new job as a professional mourner. Raakhee, Raj Babbar, and Amjad Khan appear in supporting roles. Produced by the National Film Development Corporation of India and Doordarshan, the film was labelled part of India's neo-realist parallel cinema, but it employed several of the common elements of mainstream Hindi cinema, including songs composed by Bhupen Hazarika.

Rudaali was a critical and unexpected commercial success. Particular critical praise was directed at Kapadia's performance, with further appreciation of the film's script, music, technical achievements, and Lajmi's direction. The film won three National Film Awards, including Best Actress for Kapadia, and was nominated for three Filmfare Awards, earning Kapadia a Critics Award for Best Performance. Kapadia won Best Actress honours at the 8th Damascus International Film Festival and the 38th Asia-Pacific Film Festival, where Hazarika was awarded for his music. The film was selected as the Indian entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 66th Academy Awards, but was not nominated.

Plot

[edit]Thakur Ramavtar Singh, the zamindar (transl. landlord) of Barna (a village in the desert), on his death bed, bemoans that none of his relatives would shed tears for him. He calls for a famous rudaali named Bhikni to mourn him after his death. Bhikni stays with the widow Shanichari, who lives in the Thakur's village. As their friendship grows, Shanichari tells Bhikni her life's story, which is revealed in flashbacks.

Shanichari was born on a Shanichar (Saturday), named after the planet Shani (Saturn), considered inauspicious in Hindu astrology. Shanichari is blamed by the villagers for everything bad that happens around her – from her father's death, to her mother Peewli's running off to join a theatre troupe. While still young, Shanichari is married off to Ganju, a drunkard. Her son, Budhua, whom she loves very much, likes to roam around aimlessly, just like Peewli did.

Meanwhile, the Thakur's son Lakshman Singh tells her he likes her and hires her as a maid to his wife. In his haveli, Lakshman tries to get Shanichari to assert herself against social customs and encourages her to "look up" into his eyes when speaking to him. One night, after Shanichari sings at the haveli, he gifts her a house of her own, along with two acres of land.

Ganju dies from cholera at a village fair. After curses and threats from the village pundit for not observing the prescribed customs, she takes a loan of 50 rupees to perform the rituals from Ramavatar Singh and becomes a bonded labourer under him.

Some years later, a grown up Budhua brings home Mungri, a prostitute, as his wife. Shanichari attempts to throw her out but relents on learning that she is pregnant with his child. But the snide remarks of the village pundit and shop-owners fuels conflict between the two women and in a fit of rage after a fight, Mungri aborts the child. Budhua leaves home. Shanichari tells Bhikni that none of these bereavements brought her to tears.

One night, Bhikni is called to the neighbouring village by a person named Bhishamdata. Ramavatar Singh dies a few hours later. Shanichari goes to bid farewell to Lakshman Singh, who has plans to leave the village. A messenger brings the news of Bhikni's death from the plague and tells Shanichari that Bhikni was her mother, Peewli. Shanichari then begins to weep profusely, and takes over as the new rudaali, crying at the Thakur's funeral.[2][5]

Cast

[edit]- Dimple Kapadia as Shanichari

- Rakhee as Bhikni / Peewli

- Raj Babbar as Laxman Singh

- Amjad Khan as Thakur Ramavtar Singh

- Raghubir Yadav as Budhua

- Sushmita Mukherjee as Mungri (Budhua's Wife)

Production

[edit]The film was produced by media mogul Mr. R.V.Pandit, who was also at the time the owner of famous publication house Business Press and also owner of famous magazines like Gladrags. The film is based on Mahashweta Devi's 1979 short story from the book Nairetey Megh.[6] According to author Priya Kapoor, Lajmi's casting of Kapadia, a popular film star, was a strategic choice to cater for an audience not normally drawn to feminist, experimental films like Rudaali.[7] Raakhee was cast in the role of Bhikni.[8] Amjad Khan was cast in the film in one of his final roles, and the film, which released after his death, was dedicated to him in the opening credits.[9] The film was produced by the National Film Development Corporation of India in a process that made Lajmi proclaim she would never again make a film with them.[10] Lajmi said that Kapadia felt exhausted after filming ended.[11]

In an attempt to enhance the film's visual appeal, Lajmi chose to change the setting of the story from Bengal to Rajasthan, where she planned to make use of the desertscape and the grand havelis (mansions).[12] The film was mostly shot on location in the village of Barna, located 40 km from the region of Jaisalmer in western Rajasthan,[13][14] as well as Jaisalmer Fort, Khuri desert, and Kuldhara Ruins.[6] The film's text was spoken in a West Indian dialect, though it was mildly polished for reasons of accessibility to the wider, urban viewers.[6]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film has music by folk musician Bhupen Hazarika.[9] The soundtrack album released on 18 June 1993 to great success. Business India wrote, "Rudaali is the first genuine crossover album to have negotiated the leap from art to mart, via the listeners' heart.[15]

The song "Dil Hoom Hoom Kare" is based on a previous composition by Hazarika which was used a few decades before in the Assmese film Maniram Dewan (1964) in a song called "Buku Ham Ham Kore". Gulzar, who authored the lyrics for Rudaali, was fond of the Assamese phrase "Ham Ham", used to denote beating of the heart in excitement, and insisted on using it in the Hindi song instead of the regular Hindi alternative "Dhak Dhak".[9]

All lyrics are written by Gulzar; all music is composed by Bhupen Hazarika

| No. | Title | Artist(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Dil Hoom Hoom Kare (Part-1)" (Raga: Bhoopali) | Lata Mangeshkar | |

| 2. | "Dil Hoom Hoom Kare (Part-2)" (Raga: Bhoopali) | Bhupen Hazarika | |

| 3. | "Jhuti Mooti Mitwa" (Raga: Vrindavani sarang) | Lata Mangeshkar | |

| 4. | "Samay O Dhire Chalo (Part-1)" (Raga: Bhimpalasi) | Asha Bhosle | |

| 5. | "Samay O Dhire Chalo (Part-2)" (Raga: Bhimpalasi) | Bhupen Hazarika | |

| 6. | "Moula O Moula" | Bhupen Hazarika | |

| 7. | "Samay O Dhire Chalo (Part-3)" (Raga: Bhimpalasi) | Lata Mangeshkar |

Themes

[edit]The film explores themes of caste, class stratification, gender inequality, and poverty, all portrayed through the feudal system and socio-economic marginalisation of poor villagers.[16][6] Film critic Namrata Joshi says the film "placed the issue of gender and patriarchy in the broader context of class and caste divides".[17] Sumita S. Chakravarty described it as "a film that wishes to evoke subaltern ethos".[18] Radha Subramanyam wrote that the film "explores the many levels of oppression to which the lower-caste, impoverished female is subject". She notes the film's combinatory style as it "draws on the two strains of filmmaking extant in India; it combines the social concerns of the 'art' cinema with elements of the mass appeal of Bombay films".[19] In the book India Transitions: Culture and Society during Contemporary Viral Times, Priya Kapoor calls it "a feminist treatise on solidarity against caste ostracization and the plight of the subaltern woman at the hands of landowning classes".[20] She further argued that the film came at a time when "caste and class politics have seen a disturbing resurgence in Indian politics and civilian life".[21] In another book, Intercultural Communication and Creative Practice: Music, Dance, and Women's Cultural Identity, Kapoor wrote that "Rudaali offers a chance to examine a rural community, colonial and feudal, bound by its caste location".[22]

The film's script had several diversions from the original story by Devi, including its setting and the focus of the story on the individual story, as well as the romantic tension between Shanichari and the landlord, an original addition to the film.[16] Shoma Chatterji argues that the film is so distant from its original source that those who have read it might be disappointed by the film. She added that those unfamiliar with Devi or the original story might watch Rudaali independently of its literary source. According to Chatterji, the film romanticises the tragic story of Sachichari.[23] Scholar Tutun Mukherjee wrote of the attraction that develops between Shanichari and the local landlord played by Raj Babbar and posited that given the cultural and social setting of the film, it could only take one form: "It is obvious to both that despite the romance, no relationship other than the exploitative one of the rich over poor and of man over woman can ever be allowed to develop between them."[24]

The character of Shanichari has been discussed by several writers. Author Chandra Bhushan wrote, "Shanichari is dry like a desert but even she has a flavour, affection and audacity and courage to reject the enticement of Zamindar (the landlord)."[25] According to the book Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change, Shanichari is described as "highly vulnerable to all sorts of oppressions. She resists many of them, but succumbs to the dominant discourses".[26] Reetamoni Das and Debarshi Prasad Nath, film scholars, describe Shanichari as one woman who manages to survive through her harsh realities despite the absence of a man through most of her life.[16] They further describe her as a woman who "writes her own history" as she "neither conforms to the societal constructions of the gender nor the hierarchical communal life".[16] In the view of Shreerekha Subramanian, the character of Shanichari is an embodiment of the Hindu goddess Sita or her mother Bhumi who suffer at the hands of men.[27]

The portrayal of the women of the higher caste has been discussed by Das and Nath, who claim that in Devi's story they are very much similar to their privileged male counterparts in terms of "their vanity, sham and upholding their class status", while in the film, their luxurious lifestyle and high socio-economic status notwithstanding, they are still lesser than the men in their environment and in this sense these women are not more privileged than women like Shanichari.[16] Moreover, the authors note the film's atypical portrayal of women through Shanichari's inability to cry, positioning the film as an "antithesis to the popular belief that a woman is a storehouse for tears".[16] Pillai Tripthi took note of the film's adoption into the Bollywood format "by turning the public mourning rituals into mellifluous musical performances". Tripthi made comparisons between Rudaali and Hamlet, drawing an analogy between Ophelia and Gertrude with Shanichari and Bhikni.[3]

Release and reception

[edit]Rudaali was popular with critics and the moviegoing public.[24] The film's unexpected success at the box office was attributed by author Sumita S. Chakravarty to its "ambivalent self-positioning" between mainstream and art cinema. According to Chakravarty, the lack of commercial success attained by India's alternative cinema had been due to its "shunning of the melodramatic elements of songs and emotionality, its gritty social realism", which Rudaali embraced altogether.[28]

Chidananda Dasgupta from Cinemaya noted Kapadia's performance in this film relies on both her prior experience of mainstream cinema conventions as well as her acting prowess which allows her to create a real person, believing these two elements help her make Shanichari "both larger than life and believable". Dasgupta took note of the story and Lajmi's direction as having contributed to this and added, "Together, director and actress succeed in making a mix of melodrama and realism that works". He wrote of Lajmi that "Here in the deserts of Rajasthan with the muted colours of nature and the brilliance of the costumes, she is in her element." He concluded, "To repeat Rudali's razor's edge walk between realism and melodrama may not be easy."[29] Film scholar Tutun Mukherjee described Rudaali as "cinematically appealing and spectacular woman-oriented Hindi film" and praised its quality and production values to be "superior to the usual run-of-mill Hindi formula films".[24]

Foreign reviewers were similarly appreciative of Rudaali. J. R. Jones of Chicago Reader wrote that Kapadia "acquits herself well as the determined widow".[30] Ernest Dempsey reviewed the film for the book "Recovering the Self: A Journal of Hope and Healing": "Rudaali is a must see for its realism, gripping performances (especially by Dimple Kapadia), and brilliant treatment of an unusual subject with deep psychological implications."[31] The Indologist Philip Lutgendorf described the film as "uncommon and arresting", noted its "authentic regional costumes and props, somewhat less authentic (but quite haunting) music, and two famous female stars". He appreciated both Raakhee and Kapadia for their performances but praised Kapadia in particular for her "dignity and conviction, as well as her effective body language and gestures, lift her character far beyond bathos."[32]

In a retrospective review, written for the book The Concept of Motherhood in India: Myths, Theories and Realities (2020), Shoma Chatterji expressed mixed feelings for the film. She said that despite its artistic aspiration, the film ends up being "a brazen, commercial film spilling over with the commercial ingredients of big stars, wonderful music, hummable songs, excellent production values, and picturesque landscapes." She noted that Lajmi invested the film with glamour and lavishness that was needed by the original story, and noted that while as an adaptation of Devi's story it is less successful, saying, "Lajmi loses out to the lavish mounting and the musical gimmicks of commercial cinema. She ends up denying the film the identity it deserves." In spite of this, Chatterji noted that if watched without the original story in mind, Rudaali is "entertaining and educative" in and of itself as it informs "the Indian audience about the oppression of a people it hardly knows about".[4]

Legacy

[edit]The film is one of several films based on Devi's works.[33][34] In his book The Essential Guide to Bollywood, Subhash K. Jha picked the film as one of the 200 best Hindi films ever made and wrote: "Rudaali takes us into the life of a professional mourner, played to memorable heights of sad and dry-eyed poignancy by Dimple Kapadia, who is Sanicheri, the mourner who can't weep for herself".[35] M. L. Dhawan included the film in his list of best films of that year, describing it as a "captivating melodrama", commending Kapadia's "mesmerising performance" and cocluding, "Folk tunes and songs of Rajasthan blended with Bhupen Hazarika's music against the backdrop of Rajasthani landscapes to add to grandeur to the film."[36] Film Companion wrote, "Remembered as much as for its mellifluous music, as for Dimple Kapadia's National Award-winning performance and its stark realism, Rudaali again broke new ground in terms of its subject – the lives of professional mourners."[37]

Film critic Namrata Joshi believes that for Lajmi, Rudaali is the film "that put the spotlight on her," arguing it is "perhaps the most persuasive feature film" of her career.[17] In 1994, Sudhir Bose wrote an article for Cinemaya about contemporary women directors and noted Lajmi's work in the film where Kapadia delivered a "bravura performance", which, along with Hazarika's music as well as Amjad Khan's "riveting cameo" secured the film's success.[38] The Hindustan Times wrote in 2018 in a piece about Lajmi that Rudaali is particularly noteworthy in her career "as it featured a stellar performance by Dimple Kapadia and is still remembered for its songs and music".[39] Lajmi's directorial work has been touted as one of her famous works. Raja Sen included the film in his list of 10 Best Hindi Films by Women Directors.[40] Deepa Gahlot wrote the film remains Lajmi's best-known film.[12]

Kapadia's performance is considered one of the finest of her career. Filmfare included her work in the film in its list of "80 Iconic Performances": "Dimple's phenomenal talent comes shining forth when you see years of suppressed hurt, anger and a sense of life's injustice simply flow from Shanichari's eyes."[41] Deepa Gahlot wrote for the Financial Chronicle saying the film starred Kapadia in her finest performance,[12] and included the character of Shanichari in her book of "25 Daring Women of Bollywood".[42] The Times of India said Kapadia was her best ever in the role, and similar thoughts were shared by critic Raja Sen.[43][40] In later years, Kapadia has maintained to have been discontent with parts of her performance and considered the transition her character goes through by the end of the film to be less convincing.[44]

The film's music was highly acclaimed, and Priya Singh wrote that "Rudaali's compositions are now part of the canon of world music".[21] According to The Hindu, it is this film's soundtrack which gave Hazarika "a pan-India reach".[45]

In 1999, the film was among those screened at the "Women in Indian Cinema" section at the National Museum of Women in the Arts and the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.[46][47]

According to Deccan Herald, the village of Barna where the film was shot, has become a popular tourist destination since the film's release, with visitors frequenting the place due to its association with the film for years after.[13]

Awards and honours

[edit]Rudaali was India's official entry to the 66th Academy Awards for the Indian entry for Best Foreign Language Film category.[48][49][50] It was screened at the International Film Festival of India, 1993, and the San Diego Film Festival, 1994. At the 40th National Film Awards, the film won three awards, including Best Actress for Kapadia's performance, cited as a "compelling interpretation of the tribulations of a lonely woman ravaged by a cruel society". Samir Chanda's production design won him the Best Art Direction award for his "realistic recreation of the desert scape, with its requisite architectural structures, both opulent and humble", while Simple Kapadia and Mala Dey were named the Best Costume Designers for the "authentic designs they created to blend with the desert backdrop of Rajasthan. Kapadia won a Filmfare Critics Award for Best Actress and was awarded Best Actress several honours at film festivals including the 38th Asia-Pacific Film Festival and the 8th Damascus International Film Festival. At the 39th Filmfare Awards, Rudaali was nominated for three awards. Among other awards, the film earned Lajmi accolades for direction at the V. Shantaram Awards and the All-India Critics Association (AICA) Awards. In the latter function, Rudaali was named the Best Hindi Film of the year.

| Year | Award | Category | Recipient(s) and nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 40th National Film Awards | Best Actress | Dimple Kapadia | Won | [51] |

| Best Art Direction | Samir Chanda | Won | |||

| Best Costume Design | Mala Dey and Simple Kapadia | Won | |||

| 1993 | 38th Filmfare Awards | Best Actress (Critics) | Dimple Kapadia | Won | [52] |

| 1994 | 39th Filmfare Awards | Best Actress | Dimple Kapadia | Nominated | [53] |

| Best Music Director | Bhupen Hazarika | Nominated | |||

| Best Lyricist | Gulzar for "Dil Hoom Hoom" | Nominated | |||

| 1994 | 8th Damascus International Film Festival | Best Actress | Dimple Kapadia | Won | [54] |

| 1994 | 38th Asia-Pacific Film Festival | Best Actress | Dimple Kapadia | Won | [55] |

| Best Music Director | Bhupen Hazarika | Won | |||

| 1994 | V. Shantaram Awards | Excellence in Direction | Kalpana Lajmi | Won | [56] |

| 1994 | All-India Critics Association (AICA) Awards | Best Hindi Film | Rudaali | Won | [57] |

| Best Director | Kalpana Lajmi | Won | |||

| Best Music Director | Bhupen Hazarika | Won |

See also

[edit]- List of submissions to the 66th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Indian submissions for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Rudaali", literally translated as "female weeper" or "weeping woman", refers to women of lower caste hired as professional mourners in certain areas of Rajasthan. Their job is to publicly express grief upon the death of upper-caste males on behalf of family members who are not permitted to display emotion due to social status.[2][3] The term was popularised in literature by Mahashweta Devi's 1979 short story of the same name, upon which this film is based.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Rudaali". British Board of Film Classification. 22 June 1993. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Rudaali". University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ a b Pillai, Tripthi (1 August 2020). "Mourner-confessors: The masala intercommunity of women in Rudaali and Hamlet". Postmedieval. 11 (2): 243–252. doi:10.1057/s41280-020-00178-5. ISSN 2040-5979. S2CID 225504336. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b Chatterji 2020, pp. 36–37.

- ^ "Rudaali Production Details". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d Gupta, Pragya (1 January 2008). "'Rudali': from Mahasweta Devi to Kalpana Lajmi". Creative Forum. 21 (1–2): 15–26.

- ^ Kapoor 2005, p. 103.

- ^ "Raakhee plays professional mourner in Kalpana Lajmi's Rudali". India Today. 15 April 1992. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Arunachalam 2019, p. 410.

- ^ Parasara, Noyon Jyoti (26 April 2011). "My film is stuck with NFDC: Aijaz Ahmed". The Times of India – Mumbai Mirror. The Times Group. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Gupta, Pratim D. (23 January 2006). "It is no use being eulogised after death?". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Gahlot, Deepa (28 September 2018). "The Woman Who Would Not Weep". Financial Chronicle. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ a b Mishra, Nivedita (27 May 2017). "Village capitalises on film shooting". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Perur 2018.

- ^ "For generations to come, millions will hum the golden melodies of Hazarika's Rudaali". The Indian Express. Express Group. 13 November 1993. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Das, Reetamoni; Nath, Debarshi Prasad (13 October 2014). "Rudaali in Film Narrative: Looking Through the Feminist Lens". CINEJ Cinema Journal. 3 (2): 120–139. doi:10.5195/cinej.2014.99. ISSN 2158-8724. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ a b Joshi, Namrata (23 September 2018). "Obituary | Kalpana Lajmi, one of the earliest feminist voices". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Chakravarty 1999, p. 285.

- ^ Subramanyam, Radha (1996). "Class, Caste, and Performance in "Subaltern" Feminist Film Theory and Praxis: An Analysis of "Rudaali"". Cinema Journal. 35 (3): 34–51. doi:10.2307/1225764. ISSN 0009-7101. JSTOR 1225764. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Kapoor 2020, p. 79.

- ^ a b Kapoor 2020, p. 80.

- ^ Kapoor 2005, p. 99.

- ^ Chatterji, Shoma A. (30 June 2018). "Rudali 25 Years: Manufacturing Grief by Proxy". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Mukherjee, Tutun (2010). "Of 'Text' and 'Texualities': Performing Mahasweta" (PDF). Dialog: A Bi-annual Interdisciplinary Journal. 19 (Autumn). Department of English and Cultural Studies, Panjab University: 1–20. ISSN 0975-4881. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2021.

- ^ Bhushan 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Gokulsing & Dissanayake 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Subramanian 2011, p. 83.

- ^ Chakravarty 1999, p. 299.

- ^ Dasgupta, Chidananda (1993). "Rudali (The Mourner)". Cinemaya. pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jones, J. R. (20 December 2002). "The Mourner". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Siegel et al. 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip. "Rudaali". uiowa.edu. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 5 August 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Maanvi (28 July 2016). "Mourning and Revolution: Mahasweta Devi's Legacy on the Screen". The Quint. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Ghosh, Devarsi (28 July 2016). "Mahasweta Devi, RIP: Rudaali to Sunghursh, 5 films that immortalise the author's works". India Today. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jha & Bachchan 2005, p. 78.

- ^ Dhawan, M. L. (23 March 2003). "Year of sensitive, well-made films". The Sunday Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 April 2003. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Shantanu Ray (24 September 2018). "Kalpana Lajmi, The Lady Who Dared". Film Companion.

- ^ Bose 2011.

- ^ Mishra, Nivedita (23 September 2018). "Kalpana Lajmi: 10 lesser known facts about the Rudaali director". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b Sen, Raja (14 July 2011). "Best Ever Hindi Films by Women Directors". Rediff. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "80 Iconic Performances". Filmfare. 6 June 2010.

- ^ Gahlot 2015, pp. 69–73.

- ^ "A countdown ode to Dimple". The Times of India. The Times Group. 31 August 2005. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Din, Suleman (25 May 2001). "rediff.com US edition: 'I got more than my share in life'". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Throwback Thursday: The undying music of Bhupen Hazarika". The Hindu. 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (28 February 1999). "Here & Now". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Michael (26 February 1999). "SWEET 'POP' AT HIRSHHORN". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (30 November 1993). "Acad inks Cates, unveils foreign-language entries". Variety. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2008.

- ^ "Before Gully Boy, these Indian films were sent to the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film Category". News18. 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "India's Oscar failures". India Today. 16 February 2009. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "40th National Film Awards" (PDF). dff.nic.in. Directorate of Film Festivals. 1993. pp. 40–41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ "Filmfare Awards Winners 1993: Complete list of winners of Filmfare Awards 1993". The Times of India. The Times Group. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "The Nominations – 1993". Filmfare. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Mourning Becomes Her". The Telegraph. ABP Group. 27 November 1993. p. 78. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ Kumar 2002, p. 172: "Bhupen Hazarika adjudged the best music director and Dimple Kapadia the best actress for 'Rudali' (Hindi) at Asia-Pacific International Film Festival Fukoaka, Japan"

- ^ Menon 2002, p. 243.

- ^ "'Rudali', 'Padma..' bag film critics assn. award". The Indian Express. Express Group. 9 October 1994. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Arunachalam, Param (17 August 2019). BollySwar: 1991–2000. Mavrix Infotech Private Limited. ISBN 978-81-938482-1-0. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Bhushan, Chandra (2005). Assam: Its Heritage and Culture. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7835-352-4.

- Bose, Sudhir (2 February 2011). "Contemporary Women Directors". In Doraiswamy, Rashmi; Padgaonkar, Latika (eds.). Asian Film Journeys: Selections from Cinemaya. SCB Distributors. ISBN 978-81-8328-208-6. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Chakravarty, Sumita S. (1 January 1999). "'Can the Subaltern Weep?' Mourning as Metaphor in Rudaali". In Robin, Diana Maury; Jaffe, Ira (eds.). Redirecting the Gaze: Gender, Theory, and Cinema in the Third World. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3993-7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Chatterji, Shoma A. (9 February 2020). "Myth, Motherhood, and Mainstream Hindi Cinema". In Mitra, Zinia (ed.). The Concept of Motherhood in India: Myths, Theories and Realities. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-4680-6. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Gahlot, Deepa (2015). Sheroes: 25 Daring Women of Bollywood. Westland Limited. pp. 69–73. ISBN 978-93-85152-74-0. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021.

- Gokulsing, K. Moti; Dissanayake, Wimal (2004). Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change. Trentham. ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9.

- Gulzar; Nihalani, Govind; Chatterjee, Saibal (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. Encyclopaedia Britannica (India). ISBN 978-81-7991-066-5.

- Jha, Subhash K.; Bachchan, Amitabh (2005). The Essential Guide to Bollywood. Lustre Press. ISBN 978-81-7436-378-7.

- Kapoor, Priya (20 July 2020). "India Transitions: Culture and Society during Contemporary Viral Times". In Kim, Chanwahn; Kumar, Rajiv (eds.). Great Transition In India: Critical Explorations. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-12-2235-1. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Kapoor, Priya (2005). Lengel, Laura B. (ed.). Intercultural Communication and Creative Practice: Music, Dance, and Women's Cultural Identity. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98240-9.

- Kumar, Arvind (2002). Trends in Modern Journalism. Sarup & Sons. p. 172. ISBN 978-81-7625-277-5. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013.

- Menon, Ritu (2002). Women who Dared. National Book Trust, India. ISBN 978-81-237-3856-7. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- Perur, Srinath (15 February 2018). If It's Monday It Must Be Madurai: A Conducted Tour of India. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-570-3. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94325-7.

- Sabharwal, Gopa (2007). India Since 1947: The Independent Years. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-310274-8. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014.

- Siegel, Bernie; Wing, Diane; Kenley, Holli; Levy, Jay S. (2017). Recovering the Self: A Journal of Hope and Healing (Vol. VI, No. 1) – Grief & Loss. Loving Healing Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-61599-340-6. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020.

- Subramanian, Shreerekha (2011). ""Whom Did You Lose First, Yourself or Me?": The Feminine and the Mythic in Indian Cinema". In Bahun-Radunović, Sanja; Rajan, V. G. Julie (eds.). Myth and Violence in the Contemporary Female Text: New Cassandras. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-0001-1. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1993 films

- 1990s Hindi-language films

- 1993 drama films

- Death customs

- Films about poverty in India

- Films about women in India

- Films based on short fiction

- Films based on works by Mahasweta Devi

- Films directed by Kalpana Lajmi

- Films featuring a Best Actress National Award–winning performance

- Films set in Rajasthan

- Films that won the Best Costume Design National Film Award

- Films whose production designer won the Best Production Design National Film Award

- Films about landlords