Saturday Night Fever

| Saturday Night Fever | |

|---|---|

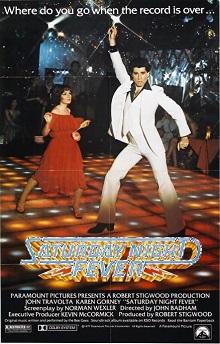

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Badham |

| Screenplay by | Norman Wexler |

| Based on | "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night" by Nik Cohn |

| Produced by | Robert Stigwood |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ralf D. Bode |

| Edited by | David Rawlins |

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date | |

Running time | 119 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million[4] |

| Box office | $237.1 million[5] |

Saturday Night Fever is a 1977 American dance drama film directed by John Badham and produced by Robert Stigwood. It stars John Travolta as Tony Manero, a young Italian-American man from the Brooklyn borough of New York. Manero spends his weekends dancing and drinking at a local discothèque while dealing with social tensions and disillusionment, feeling directionless and trapped in his working-class ethnic neighborhood. The story is based on "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night", a mostly fictional article by music writer Nik Cohn, first published in a June 1976 issue of New York magazine. The film features music by the Bee Gees and many other prominent artists of the disco era.

A major critical and commercial success, Saturday Night Fever had a tremendous impact on popular culture of the late 1970s. The film helped to popularize disco music around the world and initiated a series of collaborations between film studios and record labels. It also made Travolta, already well known from his role in the TV sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter, became a household name. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance, becoming the fifth-youngest nominee in the category. The film showcases aspects of the music, dancing, and subculture surrounding the disco era, including symphony-orchestrated melodies, haute couture styles of clothing, pre-AIDS sexual promiscuity, and graceful choreography. The Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, featuring disco songs by the Bee Gees, is one of the best-selling soundtracks in history.[6] John Travolta reprised his role of Tony Manero in Staying Alive in 1983, which was panned by critics despite being successful at the box office.

In 2010, Saturday Night Fever was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Plot

Tony Manero is a 19-year-old Italian-American from the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. He lives with his parents, grandmother, and younger sister, and works at a dead-end job in a small paint store. To escape his day-to-day life, Tony goes to 2001 Odyssey, a local discotheque, where he is king of the dance floor and receives the admiration and respect he craves. Tony has four close Italian-American friends from the neighborhood: Joey, Double J, Gus, and Bobby C. A fringe member of his group of friends is Annette, a neighborhood girl who is infatuated with Tony; however, he is not attracted to her.

Tony and his friends ritually stop on the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge to clown around. The bridge has special significance for Tony as a symbol of escape to a better life.

Tony agrees to be Annette's partner in an upcoming dance contest, but her happiness is short-lived when Tony is mesmerized by another woman at the club, Stephanie Mangano, whose dancing skills exceed Annette's. Although Stephanie rejects Tony's advances, she eventually agrees to be his partner in the dance competition, provided that their partnership remains professional.

Frank Jr., Tony's older brother and the pride of the family as a Roman Catholic priest, brings despair to their parents and grandmother when he tells them he has quit the priesthood. Tony shares a warm relationship with Frank Jr., but Tony feels pleased that he is no longer the black sheep of the family. Frank Jr. tells Tony that he never wanted to be a priest and only did it to make their parents happy. He also encourages Tony to do something with his dancing.

While on his way home from the grocery store, Gus is attacked by a gang and hospitalized. He tells Tony and his friends that his attackers were the Barracudas, a Puerto Rican gang. Meanwhile, Bobby C. has been trying to get out of his relationship with his devout Catholic girlfriend, Pauline, who is pregnant with his child. Facing pressure from his family and others to marry her, Bobby asks Frank Jr. if the Pope would grant him dispensation for an abortion. When Frank tells him such a thing would be highly unlikely, Bobby's feelings of desperation increase.

Eventually, the group gets their revenge on the Barracudas and crash Bobby C's car into their hangout. Tony, Double J, and Joey get out of the car to fight, but Bobby C. runs away when a gang member tries to attack him in the car. When the group visits Gus in the hospital, they are angry when he tells them that he may have identified the wrong gang. Later, Tony and Stephanie dance at the competition, sharing a kiss at the end of their performance, and end up winning first prize. However, Tony believes that a Puerto Rican couple performed better, and that the judges' decision was ethnically motivated. He gives the Puerto Rican couple his trophy and award money and leaves with Stephanie. Once inside Bobby's car, Stephanie mocks Tony and tells him she was using him. Tony tries to rape Stephanie, but she resists and runs from him.

Tony's friends come to the car along with an intoxicated Annette. Joey says she has agreed to have sex with everyone. Tony tries to lead her away but is subdued by Double J and Joey and sullenly leaves with the group in the car. Joey has sex with Annette in the back seat of the car. After Joey finishes with Annette, he switches places with Double J who then proceeds to rape Annette despite her loud protests, with Tony clearly uncomfortable with the situation in the front seat. Bobby C. pulls the car over on the Verrazzano–Narrows Bridge for their usual cable-climbing antics. Instead of abstaining as usual, Bobby performs stunts more recklessly than the rest of the gang. Realizing that he is acting recklessly, Tony tries to get him to come down. Bobby's strong sense of despair, the situation with Pauline, and Tony's broken promise to call him earlier that day all lead to a suicidal tirade about Tony's lack of caring, before Bobby slips and falls to his death in the water below.

Disgusted and disillusioned by his friends, his family, and his life, Tony angrily storms off, leaving Double J, Joey, and Annette behind. He spends the rest of the night riding the graffiti-riddled subway into Manhattan. Morning has dawned by the time he appears at Stephanie's apartment. He apologizes for his bad behavior, telling her that he plans to relocate from Brooklyn to Manhattan to try to start a new life. Stephanie forgives Tony, and tells him that she was wrong to say she was using him, and that she danced with him because he gave her respect and moral support. Tony and Stephanie salvage their relationship and agree to be friends.

Cast

- John Travolta as Anthony "Tony" Manero

- Karen Lynn Gorney as Stephanie Mangano

- Barry Miller as Bobby C.

- Joseph Cali as Joey

- Paul Pape as Double J.

- Donna Pescow as Annette

- Bruce Ornstein as Gus

- Val Bisoglio as Frank Manero, Sr.

- Julie Bovasso as Flo Manero

- Martin Shakar as Frank Manero, Jr.

- Lisa Peluso as Linda Manero

- Nina Hansen as Grandmother

- Sam Coppola as Dan Fusco

- Denny Dillon as Doreen

- Bert Michaels as Pete

- Fran Drescher as Connie

- Monti Rock III as the DJ

- Robert Weil as Becker

- Shelly Batt as Girl in Disco

- Donald Gantry as Jay Langhart

- Ellen March as Bartender

- William Andrews as Detective

- Robert Costanzo as paint store customer

- Helen Travolta (John's mother) as paint store customer

- Ann Travolta (John's sister) as pizza girl

Music

Soundtrack

- "Stayin' Alive" performed by the Bee Gees – 4:45

- "How Deep Is Your Love" performed by Bee Gees – 4:05

- "Night Fever" performed by Bee Gees – 3:33

- "More Than a Woman" performed by Bee Gees – 3:17

- "If I Can't Have You" performed by Yvonne Elliman – 3:00

- "A Fifth of Beethoven" performed by Walter Murphy – 3:03

- "More Than a Woman" performed by Tavares – 3:17

- "Manhattan Skyline" performed by David Shire – 4:44

- "Calypso Breakdown" performed by Ralph MacDonald – 7:50

- "Night on Disco Mountain" performed by David Shire – 5:12

- "Open Sesame" performed by Kool & the Gang – 4:01

- "Jive Talkin'" performed by Bee Gees – 3:43 (*)

- "You Should Be Dancing" performed by Bee Gees – 4:14

- "Boogie Shoes" performed by KC and the Sunshine Band – 2:17

- "Salsation" performed by David Shire – 3:50

- "K-Jee" performed by MFSB – 4:13

- "Disco Inferno" performed by The Trammps – 10:51

- With the exception of (*) track 12 "Jive Talkin", all of the songs are played in the film.

- The novelty songs "Dr. Disco" and "Disco Duck", both performed by Rick Dees, are played in the film but not included on the album.

According to the DVD commentary for Saturday Night Fever, the producers intended to use the song "Lowdown" by Boz Scaggs in the rehearsal scene between Tony and Annette in the dance studio, and choreographed their dance moves to the song. However, representatives for Scaggs' label Columbia Records refused to grant legal clearance for it, as they wanted to pursue another disco movie project, which never materialized. Composer David Shire, who scored the film, had to in turn write a song to match the dance steps demonstrated in the scene and eliminate the need for future legal hassles. However, this track does not appear on the movie's soundtrack.

The song "K-Jee" was used during the dance contest with the Puerto Rican couple that competed against Tony and Stephanie. Some VHS cassettes used a more traditional Latin-style song instead. The DVD restores the original recording.

The album, like its parent film, has been added to the Library of Congress via the National Recording Registry. [7]

Source material

Norman Wexler's screenplay was adapted from a 1976 New York magazine article by British writer Nik Cohn, "Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night". Although presented as an account of factual reporting, Cohn acknowledged in the mid-1990s that he fabricated most of the article.[8] A newcomer to the United States and a stranger to the disco lifestyle, Cohn was unable to make any sense of the subculture he had been assigned to write about; instead, the character who became Tony Manero was based on an English mod acquaintance of Cohn.[8]

Development

Shortly after Cohn's article was published, British music impresario Robert Stigwood purchased the film rights and hired Cohn to adapt his own article to screen.[9] After finishing a single screenplay draft, Cohn was replaced by Norman Wexler, who'd previously picked up Oscar nominations for Joe (1970) and Serpico (1973).

John G. Avildsen was originally hired as the film's director, but was replaced one month before principal photography by John Badham over "conceptual disagreements."[9] Badham was a lesser-known director who, like his star, had mostly worked in television. His sole prior film credit, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings, was released while Saturday Night Fever was already well into production.

The film went through several different titles, including Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night and Saturday Night. Badham chose the final title after the Bee Gees' track "Night Fever", which they submitted for the soundtrack.

Production

Casting

The film's relatively low budget ($3.5 million) meant that most of the actors were relative unknowns, many of whom were recruited from New York's theatre scene. For more than 40% of the actors it was their film debut. The only actor in the cast who was already an established name was John Travolta, thanks to his role on the sitcom Welcome Back, Kotter. His performance as Tony Manero brought him critical acclaim and helped launch him into international stardom. Travolta researched the part by visiting the real 2001 Odyssey discotheque, and claimed he adopted many of the character's swaggering mannerisms from the male patrons. He insisted on performing his character's own dance sequences after producers suggested he be substituted by a body double, rehearsing his choreography with Lester Wilson and Deney Terrio for three hours every day, losing 20 pounds in the process.

Karen Lynn Gorney was nine years older than Travolta when she was cast as his love interest Stephanie. Although Gorney had dance experience before she was cast, she found it difficult to keep up with her co-star due to injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident some years before. After the success of Saturday Night Fever, Gorney took a break from film acting to work as a dance instructor at a performing arts academy in Brooklyn. Jessica Lange, Kathleen Quinlan, Carrie Fisher, and Amy Irving were all considered for the part before Gorney was cast.

Donna Pescow was considered almost "too pretty" by Paramount heads Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg for the role of Annette. She corrected this matter by putting on weight. She also had to relearn her native Brooklyn accent, which she had overcome while studying drama at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.[10]

Filming

The film was shot entirely on-location in Brooklyn, New York. The 2001 Odyssey Disco was a real club located at 802 64th Street, which has since been demolished. The interior was modified for the film, including the addition of a $15,000 lighted floor, which was inspired by a Birmingham, Alabama establishment Badham had visited. A similar effect was achieved on the club's walls using tinfoil and Christmas lights. Since the Bee Gees were not involved in the production until after principal photography wrapped, the "Night Fever", "You Should Be Dancin'", and "More Than a Woman" sequences were shot with Stevie Wonder tracks that were later overdubbed in the sound mix. During filming, the production was harassed by local gangs over use of the location, and was even firebombed.

The dance studio was Phillips Dance Studio in Bensonhurst, the Manero home was a house in Bay Ridge,[11] the paint store was Pearson Paint & Hardware, also in Bay Ridge. Other locations included the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, John J. Carty Park, and the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

To try to throw off Travolta's fans who might disrupt filming, Badham and his team took to shooting exterior scenes as early in the morning as possible before people caught on – often at the crack of dawn. They would also generate fake call sheets. The tactics worked well enough that Badham was usually able to get the scenes done before significant crowds had time to gather.

Release

Theatrical

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Two theatrical versions of the film were released: the original R-rated version and an edited PG-rated version in 1979.[1]

The R-rated version released in 1977 represented the movie's first run, and totaled 119 minutes. After the success of the first run, the film's content was re-edited into a 112-minute, toned down, PG-rated version, not only to attract a wider audience, but also to capitalize on attracting the target audience of the teenagers who were not old enough to see the film by themselves, but who made the film's soundtrack album a monster hit. The R-rated version's profanity, nudity, fight sequence, and a multiple rape scene in a car, were all de-emphasized or removed from the PG version. Numerous profanity-filled scenes were replaced with alternate takes of the same scenes, substituting milder language initially intended for the network television cut.

Paramount planned to theatrically release the PG-rated version, which was already being shown by airlines, in 1978; however, MPAA rules at the time did not allow for two different rated versions of a film to be shown in U.S. theaters at the same time. This required the film to be withdrawn from exhibition for 90 days before a different rated version could be shown, delaying Paramount's release plans.[12] The PG-rated version was eventually released in 1979 and was later paired by Paramount in a double feature along with its other John Travolta blockbuster, Grease.[13] In the A&E documentary The Inside Story: Saturday Night Fever, producer Robert Stigwood critiqued of the PG-rated version:

It ruined the film. It doesn't have the power, or the impact, of the original, R-rated edition.

In 2017, the director's cut (running 122 minutes) premiered at the TCM Classic Film Festival at TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Fathom Events hosted special screenings of this version in 2017.

Home media

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Both theatrical versions were released on VHS. The PG-rated version never had a home video release on Laserdisc. The R-rated special-edition DVD release includes most of the deleted scenes present on the PG version, as well as a director's commentary and "Behind the Music" featurettes.

On May 5, 2009, Paramount released Saturday Night Fever on Blu-ray Disc in 1.78:1 aspect ratio. This release retains the R-rated version of the film, in addition to including many special features new to home media.[14]

The 4K director's cut (122 minutes) was released on Blu-ray on May 2, 2017. This disc includes both the director's cut and the original theatrical version, as well as the bulk of the bonus features from the prior release.

Television broadcast

When HBO acquired the pay television rights to Saturday Night Fever in 1980, both versions of the film were aired by the network: the PG version during the day, and the R version during the evening. (HBO, which had primarily operated on a late afternoon-to-early overnight schedule at the time, had maintained a programming policy restricting the showing of R-rated films to the nighttime hours, a rule that continued long after it switched to a 24-hour schedule full-time in December 1981.) The R-rated theatrical version premiered on the network at midnight Eastern Time on January 1, 1980.

For the film's network television premiere, airing on ABC on November 16, 1980, a new milder version was created to conform with network broadcast standards. The network television version—which is among the longest cuts of the film—was basically a slightly shortened cut of the PG-rated version, but to maintain runtime, a few additional scenes deleted from both theatrical releases were restored to make up for the lost/cut material (including Tony dancing with Doreen to "Disco Duck", Tony running his finger along the cables of the Verrazzano–Narrows Bridge, and Tony's father getting his job back). The last two deleted scenes were included in the 2017 director's cut.

Starting in the late 1990s, VH1, TBS and TNT began showing the original R-rated version with a TV-14 rating, although with nudity removed/censored, and the stronger profanity either being edited or (on recent airings) silenced. However, this version of the TV cut included some innuendo included in the original theatrical release that was edited or removed from the PG version. Turner Classic Movies has aired the film in both versions: the original R-rated version (rated TV-MA on the network) is the cut commonly broadcast, although the PG cut has been presented as part of TCM's family-oriented "Funday Night at the Movies" and "Essentials Jr." film showcases.

Reception

Box office

The film grossed $25.9 million in its first 24 days of release and grossed an average of $600,000 a day throughout January to March[15] going on to gross $94.2 million in the United States and Canada and $237.1 million worldwide.[5]

Critical response

Saturday Night Fever received positive reviews and is regarded by many critics as one of the best films of 1977.[16][17][18][19] On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 83% based on 53 reviews, with an average rating of 7.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Boasting a smart, poignant story, a classic soundtrack, and a starmaking performance from John Travolta, Saturday Night Fever ranks among the finest dramas of the 1970s."[20] At Metacritic the film has a score of 77 out of 100, based on 7 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[21] It was added to The New York Times "Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made", which was published in 2004.[22] In 2010, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Film critic Gene Siskel, who would later list this as his favorite movie, praised the film: "One minute into Saturday Night Fever you know this picture is onto something, that it knows what it's talking about." He also praised John Travolta's energetic performance: "Travolta on the dance floor is like a peacock on amphetamines. He struts like crazy."[23] Siskel even bought Travolta's famous white suit from the film at a charity auction.[24]

Film critic Pauline Kael wrote a gushing review of the film in The New Yorker: "The way Saturday Night Fever has been directed and shot, we feel the languorous pull of the discotheque, and the gaudiness is transformed. These are among the most hypnotically beautiful pop dance scenes ever filmed ... Travolta gets so far inside the role he seems incapable of a false note; even the Brooklyn accent sounds unerring ... At its best, though, Saturday Night Fever gets at something deeply romantic: the need to move, to dance, and the need to be who you'd like to be. Nirvana is the dance; when the music stops, you return to being ordinary."[25][26]

Historians of disco have criticized the film as a whitewashed representation of disco. Katherine Karlin wrote: "The film is wrongly credited with sparking the disco culture; it’s more accurate to say that it marks the moment when disco—up to that moment a megaphone for voices that were queer, black, or female—became accessible to straight white men, and thus the moment marking its decline."[27] Music historians Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton wrote in their book "Last Night a DJ Saved My Life": "The Bee Gees did for disco what Elvis Presley did for rhythm and blues, what Diana Ross did for soul, what Dave Brubeck did for jazz; they made it safe for white, straight, middle-class people, hauling it out of its subcultural ghetto and into the headlight glare of the mainstream. Here was something middle America could move its uptight ass to."[28]

Accolades

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Songs:

- Stayin' Alive – #9

- More Than a Woman – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Cheers – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated

In popular culture

The 1980 comedy Airplane! by directors David & Jerry Zucker and Jim Abrahams, included a flashback scene that directly parodied the dance competition scene at the disco in Saturday Night Fever.

In 2008, director Pablo Larraín made a film, Tony Manero, about a Chilean dancer obsessed by the main character in Saturday Night Fever who tries to win a Tony Manero look-alike contest.[41]

On April 17, 2012, Fox aired series Glee's episode 16, "Saturday Night Glee-ver", which pays tribute to the film and features various songs from its soundtrack (especially the songs performed by the Bee Gees), covered by the series' cast.[42][43]

The Red Hot Chili Peppers 2016 music video for their song "Go Robot" is heavily inspired by the film and recreates the opening scene and classic characters from the film who are portrayed by each band member.[44]

References

- ^ a b c d Saturday Night Fever at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ History.com

- ^ "Saturday Night Fever (1977)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ Loftis, Ryan (December 12, 2012), Saturday Night Fever Turns 35. Suite101. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Saturday Night Fever, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ^ Bee Gees' Maurice Gibb dies. USA Today (January 12, 2003).

- ^ Richards, Chris. "Library of Congress adds 'Saturday Night Fever,' Simon and Garfunkel, Pink Floyd to audio archive – San Jose Mercury News". Mercurynews.com. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Leduff, Charlie (June 9, 1996). "Saturday Night Fever: The Life". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Gelder, BY Lawrence Van (January 6, 1978). "New race: Donna Pescow (Published 1978)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "Bay Ridge Still Has Saturday Night Fever, 35 Years Later". brooklynbased.com. December 14, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Segers, Frank (May 31, 1978). "Par Asks, Then Drops, Request MPAA Give Two Ratings Of Pic, With No 90-Day Withdrawal". Variety. p. 3.

- ^ Gold, Aaron (March 27, 1979). "Tower Ticker". Chicago Tribune. pp. A7.

- ^ Terrence, Sir (May 8, 2009). "Saturday Night Fever Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Blu-ray.com. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "'Sat. Nite Fever' At $87,749,000". Variety. May 10, 1978. p. 4.

- ^ "Gene Siskel's Top Ten Lists 1969–1998". Alumnus.caltech.edu. February 20, 1999. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Greatest Films of 1977: "melodramatic, out-dated blockbuster"". Filmsite.org. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ MaryAnn Johanson (May 25, 2007). "The 10 Best Movies of 1977 – Movies". Film.com. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 1977 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Saturday Night Fever". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ EvanW. "Saturday Night Fever". Metacritic. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 16, 1977). "Energy, reality make 'Fever' dance". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 7, 1999). "Saturday Night Fever (1977)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "Critics' Corner – Saturday Night Fever". TCM.com. Tcm.com. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (December 26, 1977). "Nirvana". The New Yorker. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Karlin, Katherine (June 12, 2019). "What We Don't Remember About Saturday Night Fever". Bright Wall/Dark Room. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Brewster, Bill; Broughton, Frank (December 2007). Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey. New York: Grove Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-55584-611-4.

- ^ "The 50th Academy Awards (1978)". oscars.org. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1979". BAFTA. 1979. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "DVD PREMIERE AWARDS 2002 NOMINATIONS & WINNERS". DVD Exclusive Magazine. Archived from the original on February 17, 2006.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; January 14, 2005 suggested (help) - ^ "Saturday Night Fever – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1977 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ "1978 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame". Grammy.com. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ "1977 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1977 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". wga.org. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (July 2, 2009). "The Dictator and the Disco King". The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ Harnick, Chris (April 13, 2012). "WATCH: 'Glee' Goes Disco". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Entertainment News, Photos and Videos – HuffPost Entertainment

- ^ Ivie, Devon (September 9, 2016). "Anthony Kiedis Makes a White-Painted Saturday Night Fever Homage in the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 'Go Robot' Video". New York.

External links

- Saturday Night Fever at IMDb

- Saturday Night Fever at the TCM Movie Database

- Saturday Night Fever at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Saturday Night Fever Paramountmovies.com

- 1977 films

- 1970s coming-of-age drama films

- 1970s dance films

- 1970s American films

- 1977 drama films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American dance films

- Casual sex in films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films about dysfunctional families

- Films about friendship

- Films based on newspaper and magazine articles

- Films based on short fiction

- Films directed by John Badham

- Films produced by Robert Stigwood

- Films scored by David Shire

- Films set in Brooklyn

- Films shot in New York City

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by Norman Wexler

- United States National Film Registry films

- Disco films

- Films about Italian-American culture

- 1970s Italian-language films