Savannah, Georgia

Savannah, Georgia | |

|---|---|

| City of Savannah | |

|

Clockwise from top: downtown Savannah viewed from Bay Street, Forsyth Park, River Street, Talmadge Memorial Bridge with the Port of Savannah on the Savannah River, Savannah Victorian Historic District, Savannah College of Art and Design, Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, Congregation Mickve Israel, Savannah Historic District, | |

| Nickname: "The Hostess City of the South" | |

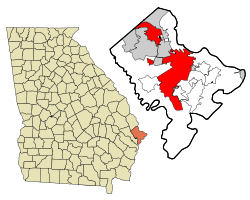

Location in Chatham County and the state of Georgia | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Chatham |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Eddie DeLoach |

| • City Manager | Stephanie Cutter (Acting) |

| Area | |

| • City | 108.7 sq mi (281.5 km2) |

| • Land | 103.1 sq mi (267.1 km2) |

| • Water | 5.6 sq mi (14.4 km2) |

| Elevation | 49 ft (15 m) |

| Population (est. 2014) | |

| • City | 144,352 |

| • Density | 1,321.2/sq mi (510.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 372,708 |

| • Demonym | Savannahian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 31401-31499 |

| Area code | 912 |

| FIPS code | 13-69000[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0322590[2] |

| Website | SavannahGA.gov |

Savannah (/səˈvænə/) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia.[3] A strategic port city in the American Revolution and during the American Civil War,[4] Savannah is today an industrial center and an important Atlantic seaport. It is Georgia's fifth-largest city and third-largest metropolitan area.

Each year Savannah attracts millions of visitors to its cobblestone streets, parks, and notable historic buildings: the birthplace of Juliette Gordon Low (founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA), the Georgia Historical Society (the oldest continually operating historical society in the South), the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences (one of the South's first public museums), the First African Baptist Church (one of the oldest African-American Baptist congregations in the United States), Temple Mickve Israel (the third oldest synagogue in America), and the Central of Georgia Railway roundhouse complex (the oldest standing antebellum rail facility in America).[3][5]

Savannah's downtown area, which includes the Savannah Historic District, the Savannah Victorian Historic District, and 22 parklike squares, is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the United States (designated by the U.S. government in 1966).[3][a] Downtown Savannah largely retains the original town plan prescribed by founder James Oglethorpe (a design now known as the Oglethorpe Plan). Savannah was the host city for the sailing competitions during the 1996 Summer Olympics held in Atlanta.

History

On February 12, 1733,[6] General James Oglethorpe and settlers from the ship Anne landed at Yamacraw Bluff and were greeted by Tomochichi, the Yamacraws, and Indian traders John and Mary Musgrove. Mary Musgrove often served as an interpreter. The city of Savannah was founded on that date, along with the colony of Georgia. In 1751, Savannah and the rest of Georgia became a Royal Colony and Savannah was made the colonial capital of Georgia.[7] By the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, Savannah had become the southernmost commercial port of the Thirteen Colonies. British troops took the city in 1778, and the following year a combined force of American and French soldiers failed to rout the British at the Siege of Savannah. The British did not leave the city until July 1782.[8] Savannah, a prosperous seaport throughout the nineteenth century, was the Confederacy's sixth most populous city and the prime objective of General William T. Sherman's March to the Sea. Early on December 21, 1864, local authorities negotiated a peaceful surrender to save Savannah from destruction, and Union troops marched into the city at dawn.[9]

Savannah was named for the Savannah River, which probably derives from variant names for the Shawnee, a Native American people who migrated to the river in the 1680s. The Shawnee destroyed another Native people, the Westo, and occupied their lands at the head of the Savannah River's navigation on the fall line, near present-day Augusta.[10] These Shawnee, whose Native name was Ša·wano·ki (literally, "southerners"),[11] were known by several local variants, including Shawano, Savano, Savana and Savannah.[12] Another theory is that the name Savannah refers to the extensive marshlands surrounding the river for miles inland, and is derived from the English term "savanna", a kind of tropical grassland, which was borrowed by the English from Spanish sabana and used in the Southern Colonies. (The Spanish word comes from the Taino word zabana.)[13] Still other theories suggest that the name Savannah originates from Algonquian terms meaning not only "southerners" but perhaps "salt".[14][15]

Geography

Savannah lies on the Savannah River, approximately 20 mi (32 km) upriver from the Atlantic Ocean.[16] According to the United States Census Bureau (2011), the city has a total area of 108.7 square miles (281.5 km2), of which 103.1 square miles (267.0 km2) is land and 5.6 square miles (15 km2) is water (5.15%). Savannah is the primary port on the Savannah River and the largest port in the state of Georgia. It is also located near the U.S. Intracoastal Waterway. Georgia's Ogeechee River flows toward the Atlantic Ocean some 16 miles (26 km) south of downtown Savannah.

Savannah is prone to flooding. Five canals and several pumping stations have been built to help reduce the effects: Fell Street Canal, Pipe Makers Canal, Kayton Canal, Springfield Canal and Casey Canal, the first four draining north into the Savannah River and the last, the Casey, draining south into the Vernon River.

Climate

Savannah's climate is classified as humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa). In the Deep South this climate is characterized by long and almost tropical summers, with temperatures reaching freezing on only 24 days in the winter (and with rare snowfall). Due to its proximity to the Atlantic coast, Savannah rarely experiences temperatures as extreme as those in Georgia's interior. Nevertheless, the extreme temperatures have officially ranged from 105 °F (41 °C), as recently as July 20, 1986, down to 3 °F (−16 °C), on January 21, 1985.[17]

Summers tend to be humid with many thunderstorms. Nearly half of Savannah's precipitation falls during the months of June through September, characteristic of monsoon-type climates. Dewpoint in summer ranges from 67.8 °F (20 °C) to 71.6 °F (22 °C).[18] As the city is south of the snow line, it rarely receives snow in winter. Occasional Arctic cold fronts in winter can push nighttime temperatures as low as 20 °F (−7 °C), but rarely further than that.[18][19] Savannah straddles two recognized plant-hardiness zones: 8b, which is no colder than 15 °F (−9 °C), and 9a, no colder than 20 °F (−7 °C).[5]

Savannah is at risk for hurricanes, particularly of the Cape Verde type. Because of its location in the Georgia Bight (the arc of the Atlantic coastline in Georgia and northern Florida) as well as the tendency for hurricanes to re-curve up the coast, Savannah has a lower risk of hurricanes than some other coastal cities such as Charleston, South Carolina. Savannah was seldom affected by hurricanes during the 20th century, with one exception being Hurricane David in 1979. However, the historical record shows that the city was frequently affected during the second half of the 19th century. The most prominent of these storms was the 1893 Sea Islands hurricane, which killed at least 2,000 people. (This estimate may be low, as deaths among the many impoverished rural African-Americans living on Georgia's barrier islands may not have been reported.)

Template:Savannah, Georgia weatherbox

The first meteorological observations in Savannah probably occurred at Oglethorpe Barracks circa 1827, continuing intermittently until 1850 and resuming in 1866. The Signal Service began observations in 1874, and the National Weather Service has kept records of most data continually since then; since 1948, Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport has served as Savannah's official meteorological station. Annual records (dating back to 1950) from the airport's weather station are available on the web.[20]

Urban

Neighborhoods

Savannah is a city of diverse neighborhoods. More than 100 distinct neighborhoods can be identified in six principal areas of the city: Downtown (Landmark Historic District and Victorian District), Midtown, Southside, Eastside, Westside, and Southwest/West Chatham (recently annexed suburban neighborhoods).

Historic districts

Besides the Savannah Historic District, one of the nation's largest, four other historic districts have been formally demarcated:[21]

- Victorian District

- Cuyler-Brownsville District

- Mid-City (Thomas Square) District

- Pin Point Historic District

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 5,146 | — | |

| 1810 | 5,215 | 1.3% | |

| 1820 | 7,523 | 44.3% | |

| 1830 | 7,303 | −2.9% | |

| 1840 | 11,214 | 53.6% | |

| 1850 | 15,312 | 36.5% | |

| 1860 | 22,292 | 45.6% | |

| 1870 | 28,235 | 26.7% | |

| 1880 | 30,709 | 8.8% | |

| 1890 | 43,189 | 40.6% | |

| 1900 | 54,244 | 25.6% | |

| 1910 | 65,064 | 19.9% | |

| 1920 | 83,252 | 28.0% | |

| 1930 | 85,024 | 2.1% | |

| 1940 | 95,996 | 12.9% | |

| 1950 | 119,638 | 24.6% | |

| 1960 | 149,245 | 24.7% | |

| 1970 | 118,349 | −20.7% | |

| 1980 | 141,654 | 19.7% | |

| 1990 | 137,560 | −2.9% | |

| 2000 | 131,510 | −4.4% | |

| 2010 | 136,286 | 3.6% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 144,352 | [22] | 5.9% |

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Savannah's 2014 estimated population was 144,352, up from the official 2010 count of 136,286 residents.[24] The Census Bureau estimated the 2014 population of the Savannah Metropolitan Statistical Area (defined by the Census Bureau as Bryan, Chatham, and Effingham counties) to be 372,708.[25] Between 2000 and 2010, Savannah's metro area had grown from 293,000 to 347,611, an increase of 18.6 percent.[26] Savannah is also the largest principal city of the Savannah-Hinesville-Statesboro Combined Statistical Area, a larger trading area that includes the Savannah and Hinesville-Fort Stewart metropolitan areas and (since 2012) the Statesboro Micropolitan Statistical Area. The 2014 estimated population of this area was 527,106, up from 495,745 at the 2010 Census.[27]

In the official 2010 census of Savannah, there were 136,286 people, 52,615 households, and 31,390 families residing in the city.[28] The population density was 1,759.5 people per square mile (679.4/km²). There were 57,437 housing units at an average density of 768.5 per square mile (296.7/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 55.04% Black, 38.03% White, 2.00% Asian, 0.03% Native American, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.93% from other races, and 2.01% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.07% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 32.6% of the population in 2010,[28] compared to 46.2% in 1990.[29]

There were 51,375 households out of which 28.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.2% were married couples living together, 21.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.9% were non-families. 31.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.13.

In the city the age distribution was as follows: 25.6% were under the age of 18, 13.2% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 19.5% from 45 to 64, and 13.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 89.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,038, and the median income for a family was $36,410. Males had a median income of $28,545 versus $22,309 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,921. About 17.7% of families and 21.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.4% of those under age 18 and 15.1% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Savannah adopted a council-manager form of government in 1954. The city council consists of the mayor and eight aldermen, six of whom are elected from one of six aldermanic districts, with each district electing one member. The other two members and the mayor are elected at-large.

The council levies taxes, enacts ordinances, adopts the annual budget, and appoints the City Manager.[30] The City Manager enacts the policies and programs established by council, recommends an annual budget and work programs, appoints bureau and department heads, and exercises general supervision and control over all employees of the city.[30]

Police, fire department, and Savannah-Chatham consolidation

In 2003 Savannah and Chatham County voted to merge their city and county police departments. The Savannah-Chatham Metropolitan Police Department was established on January 1, 2005, after the Savannah Police Department and Chatham County Police Department merged. The department has a number of specialty units, including: K-9, SWAT, Bomb Squad, Marine Patrol, Dive, Air Support and Mounted Patrol. The 9-1-1 Communications Dispatch Center handles all 9-1-1 calls for service within the county and city, including fire and EMS. The Savannah Fire Department only serves the City of Savannah and remains separate from the other municipal firefighting organizations in Chatham County.

While some[who?] see the police merger as a step toward city-county consolidation, Savannah is actually one of eight incorporated cities or towns in Chatham County. (The others are Bloomingdale, Garden City, Pooler, Port Wentworth, Thunderbolt, Tybee Island and Vernonburg). Although these seven smaller localities would remain independent from a consolidated government, they have long opposed any efforts to adopt a city-county merger. One fear is that consolidation would reduce county funding to areas outside of Savannah.[citation needed]

State representation

The Georgia Department of Corrections operates the Coastal State Prison in Savannah.[31][32]

Economy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

Agriculture was essential to Savannah's economy during its first two centuries. Silk and indigo production, both in demand in England, were early export commodities. By 1767, almost a ton of silk per year was exported to England.[33]

Georgia's mild climate offered perfect conditions for growing cotton, which became the dominant commodity after the American Revolution. Its production under the plantation system and shipment through the Port of Savannah helped the city's European immigrants to achieve wealth and prosperity.

In the nineteenth century, the Port of Savannah became one of the most active in the United States, and Savannahians had the opportunity to consume some of the world's finest goods, imported by foreign merchants. Savannah's port has always been a mainstay of the city's economy. In the early years of the United States, goods produced in the New World had to pass through Atlantic ports such as Savannah's before they could be shipped to England.

Between 1912 and 1968, the Savannah Machine & Foundry Company was a shipbuilder in Savannah.[34]

Today,[when?] the Port of Savannah, manufacturing, the military, and the tourism industry are Savannah's four major economic drivers. In 2006, the Savannah Area Convention & Visitors Bureau reported over 6.85 million visitors to the city during the year. By 2011, the Bureau reported that the number of visitors the city attracted increased to 12.1 million. Lodging, dining, entertainment, and visitor-related transportation account for over $2 billion in visitors' spending per year and employ over 17,000.

For years, Savannah was the home of Union Camp, which housed the world's largest paper mill. The plant is now owned by International Paper, and it remains one of Savannah's largest employers. Savannah is also home to the Gulfstream Aerospace company, maker of private jets, as well as various other large industrial interests. TitleMax is headquartered in Savannah. Morris Multimedia, a newspaper and television company, is also based in Savannah.

In 2000, JCB, the third largest producer of construction equipment in the world and the leading manufacturer of backhoes and telescopic handlers, built its North American headquarters in Chatham County near Savannah in Pooler on I-95 near Savannah-Hilton Head International Airport.

In 2009-2014, Savannah was North America's fourth largest port for shipping container traffic.[35]

Arts and culture

Beyond its architectural significance as being the nation's largest, historically restored urban area, the city of Savannah has a rich and growing performing arts scene, offering cultural events throughout the year.

Books and literature

- The Savannah Book Festival – an annual book fair held on Presidents' Day weekend in the vicinity of historic Telfair and Wright squares, includes free presentations by more than 35 contemporary authors. Special events with featured writers are offered at nominal cost throughout the year.[36]

- Flannery O'Connor Childhood Home[37] – a museum house dedicated to the work and life of the acclaimed fiction writer Flannery O'Connor, who was born in Savannah. In addition to its museum, the house offers literary programming, including the annual Ursrey Lecture honoring American fiction writers.[38]

Dance

Savannah Ballet Theatre – established in 1998 as a nonprofit organization, it has grown to become the city’s largest dance company.[39]

Music

- The Coastal Jazz Association – presents a variety of jazz performances throughout the year in addition to hosting the annual Savannah Jazz Festival.[40]

- Savannah Children's Choir – non-profit, auditioned choir for children in 2nd through 8th grades that performs throughout the community and in annual holiday and spring concerts.[41]

- Savannah Concert Association – presents a variety of guest artists for chamber music performances each season. Performances are generally held in the Lucas Theatre For The Arts.[42]

- Savannah Music Festival – an annual music festival of diverse artists which is Georgia's largest musical arts festival and is nationally recognized as one of the best music festivals in the world.

- The Savannah Orchestra – Savannah's professional orchestra, which presents an annual season of classical and popular concert performances.[43]

- The Savannah Philharmonic – professional orchestral and choral organization presenting year round concerts (classical, pops, education).[44]

- The Savannah Winds – amateur concert band hosted by the music department of Armstrong Atlantic State University.[45]

- The Armstrong Youth Orchestra – Savannah's professional orchestra for elementary, middle school, high school and some college students.[46]

Rock music

Several sludge metal groups have emerged from Savannah.[47] Included in these are Baroness, Kylesa, Black Tusk and Circle Takes the Square.[47]

Theater and performance

- Muse Arts Warehouse – founded in 2010, Muse Arts Warehouse is a nonprofit organization committed to community-building through the arts by providing a venue that is available, affordable, and accessible to Savannah's individual artists, arts organizations and the public.[48]

- Savannah Children's Theatre – a non-profit, year-round drama theater company geared toward offering elementary through high school students (and adults) opportunities for participation in dramatic and musical productions.[49]

- Savannah Community Theatre – a full theater season with a diverse programming schedule, featuring some of Savannah's finest actors in an intimate, three-quarter-round space.[50]

- Little Theatre of Savannah – founded in 1950, The Little Theatre of Savannah, Inc., is a nonprofit, volunteer-based community organization dedicated to the celebration of the theater arts. Recognizing the unique social value, expressive fulfillment and opportunity for personal growth that theater provides its participants, the Little Theatre of Savannah invites all members of the community to participate both on- and off-stage.[51]

- The Savannah Theatre – Savannah's only fully professional resident theater, producing music revues with live singers, dancers and the most rockin' band in town. Performances happen year-round, with several different titles and a holiday show.[52]

- Lucas Theatre for the Arts – founded in December 1921, the Lucas Theatre is one of several theaters owned by the Savannah College of Art and Design. It hosts the annual Savannah Film Festival.

- Trustees Theater – once known as the Weis Theater, which opened February 14, 1946, this theater reopened as the Trustees Theater on May 9, 1998, and hosts a variety of performances and concerts sponsored by the Savannah College of Art and Design. SCAD also owns the building.

Points of interest

Savannah's architecture, history, and reputation for Southern charm and hospitality are internationally known. The city's former promotional name was "Hostess City of the South," a phrase still used by the city government.[53][54] An earlier nickname was "the Forest City", in reference to the large population and species of oak trees that flourish in the Savannah area. These trees were especially valuable in shipbuilding during the 19th century.[55] In 2014, Savannah attracted 13.5 million visitors from across the country and around the world.[56] Savannah's downtown area is one of the largest National Historic Landmark Districts in the United States.[7]

The city's location offers visitors access to the coastal islands and the Savannah Riverfront, both popular tourist destinations. Tybee Island, formerly known as "Savannah Beach", is the site of the Tybee Island Light Station, the first lighthouse on the southern Atlantic coast. Other picturesque towns adjacent to Savannah include the shrimping village of Thunderbolt and three residential areas that began as summer resort communities for Savannahians: Beaulieu, Vernonburg, and the Isle of Hope.

The Savannah International Trade & Convention Center is located on Hutchinson Island, across from downtown Savannah and surrounded by the Savannah River. The Belles Ferry connects the island with the mainland, as does the Eugene Talmadge Memorial Bridge.

The Savannah Civic Center on Montgomery Street is host to more than nine hundred events each year.

Savannah has consistently been named one of "America's Favorite Cities" by Travel + Leisure. In 2012, the magazine rated Savannah highest in "Quality of Life and Visitor Experience."[57] Savannah was also ranked first for "Public Parks and Outdoor Access," visiting in the Fall, and as a romantic escape.[58] Savannah was also named as America's second-best city for "Cool Buildings and Architecture," behind only Chicago.[59]

Squares

Savannah's historic district has 22 squares (Ellis Square, demolished in 1954, was fully restored in early 2010).[60][61] The squares vary in size and character, from the formal fountain and monuments of the largest, Johnson, to the playgrounds of the smallest, Crawford. Elbert, Ellis, and Liberty Squares are classified as the three "lost squares," destroyed in the course of urban development during the 1950s. Elbert and Liberty Squares were paved over to make way for a realignment of U.S. highway 17, while Ellis Square was demolished to build the City Market parking garage. The city restored Ellis Square after razing the City Market parking garage. The garage has been rebuilt as an underground facility, the Whitaker Street Parking Garage, and it opened in January 2009. The newly restored Ellis Square opened in March 2010.[62] Separate efforts are now under way to revive Elbert and Liberty Squares.

Historic churches and synagogues

Savannah has numerous historic houses of worship.

Founded in 1733, with the establishment of the Georgia colony, Christ Church (Episcopal) is the longest continuous Christian congregation in Georgia.[citation needed] Early rectors include the Methodist evangelists John Wesley and George Whitefield. Located on the original site on Johnson Square, Christ Church continues as an active congregation.

The Independent Presbyterian Church (Savannah, Georgia), which was founded in 1755, is located near Chippewa Square. The church's current sanctuary (its third) dates from the early 1890s.

The First Bryan Baptist Church is an African-American church that was organized by Andrew Bryan in 1788. The site was purchased in 1793 by Bryan, a former slave who had also purchased his freedom. The first structure was erected there in 1794. By 1800, the congregation was large enough to split: those at Bryan Street took the name of First African Baptist Church, and Second and Third African Baptist churches were also established.[63] The current sanctuary of First Bryan Baptist Church was constructed in 1873.

In 1832, a controversy over doctrine caused the First African Baptist congregation at Bryan Street to split. Some members left, taking with them the name of First African Baptist Church. In 1859, the members of this new congregation (most of whom were slaves) built their current church building on Franklin Square.[63]

In 1874, the St. Benedict the Moor Church was founded in Savannah, the first African-American Catholic church in Georgia, and one of the oldest in the Southeast.[64]

The oldest standing house of worship is First Baptist Church, Savannah (1833), located on Chippewa Square. Other historic houses of worship in Savannah include: Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (Roman Catholic), Temple Mickve Israel (the third oldest synagogue in the U.S.),[3] and St. John's Church (Episcopal).

Historic homes

Among the historic homes that have been preserved are: the Pink House, the Sorrel-Weed House, Juliette Gordon Low's birthplace, the Davenport House Museum, the Green-Meldrim House, the Owens-Thomas House, the William Scarbrough House, and the Wormsloe plantation of Noble Jones. The Mercer-Williams House, the former home of Jim Williams, is the main location of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

Historic cemeteries

Colonial Park Cemetery (an early graveyard dating back to the English colony of Georgia), Laurel Grove Cemetery (with the graves of many Confederate soldiers and African American slaves) and Bonaventure Cemetery (a former plantation and the final resting place for some illustrious Savannahians).

Historic forts

Fort Jackson, not associated with Andrew Jackson, one mile east of Savannah's Historic District, was originally built between 1808 and 1812 to protect the city from attack by sea. During the Civil War, it became one of three Confederate forts defending Savannah from Union forces. Fort Pulaski National Monument, located 17 miles (27 km) east of Savannah, preserves the largest fort protecting Savannah during the Civil War. The Union Army attacked Fort Pulaski in 1862, with the aid of a new rifled cannon that effectively rendered brick fortifications obsolete.

Other registered historic sites

- Savannah Historic District and the Savannah Victorian Historic District

- Forsyth Park

- Juliette Gordon Low Historic District

- Central of Georgia Railroad: Savannah Shops and Terminal Facilities and Central of Georgia Depot and Trainshed – a 33.2-acre (134,000 m2) historic district that was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.[65][66]

- Riverfront Plaza and Factors' Walk – River Street's restored nineteenth-century cotton warehouses and passageways include shops, bars and restaurants

- City Market – Savannah's restored central market features antiques, souvenirs, small eateries, as well as two large outdoor plazas

- Savannah State University campus and Walter Bernard Hill Hall – The Georgia Historical Commission and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources have recognized both the Savannah State campus and Hill Hall as a part of the Georgia Historical Marker Program.[67] Hill Hall, which was built in 1901, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1981.[68]

- Telfair Museum of Art and Telfair Academy of Arts of Sciences – the South’s first public art museum.

- Wormsloe Plantation – the partially restored house and grounds of an 18th-century Georgia plantation.

Shopping

Various centers for shopping exist about the city including Abercorn Common, Savannah Historic District, Oglethorpe Mall, Savannah Mall and Abercorn Walk.

Other attractions

- Club One – home of The Lady Chablis and made famous in the book and movie Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.[69]

- Coastal Georgia Botanical Gardens - a developing botanical garden located at Bamboo Farm, a former USDA plant-introduction station south of Savannah that began operations in 1919.

- Oatland Island Wildlife Center – located east of Savannah, a facility owned and operated by the Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education and featuring wildlife from surrounding coastal Georgia and South Carolina.

- Ossabaw Island – an environmentally protected and commercially undeveloped barrier island south of Savannah.

- Pinkie Masters Bar - a popular Savannah watering hole and the site of presidential visits and political campaigns. Pinkie Masters was a local political figure and a friend of President Jimmy Carter, who made several visits to the bar and the city.

- Pirates' House – historic restaurant and tavern located in downtown Savannah.

- Saint Patrick's Day Celebrations – Savannah holds annual celebrations in honor of Saint Patrick's Day. The actual parade route changes from year to year but usually travels through the Savannah Historic District and along Bay Street. The Savannah Waterfront Association has an annual celebration on River Street that is reminiscent of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street in New Orleans.

- Skidaway Island – an affluent suburban community south of Savannah that hosts Skidaway Island State Park, the University of Georgia Aquarium and the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

- Tybee Island – popular Atlantic resort town 17 mi (27 km) east of Savannah, with public beaches, a lighthouse, and other attractions.

Sports and recreation

Professional sport teams

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Championships | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savannah Braves | Baseball | Southern League | Grayson Stadium | 0 | 1971–1983 |

| Savannah Cardinals | Baseball | South Atlantic League | Grayson Stadium | 2 (1993, 1994) | 1984–1995 |

| Savannah Sand Gnats | Baseball | South Atlantic League | Grayson Stadium | 2 (1996, 2013) | 1996–2015 |

| Savannah Spirits | Basketball | Continental Basketball Association | Savannah Civic Center | 0 | 1986–1988 |

| Savannah Wildcats | Basketball | Continental Basketball League | Armstrong State University | 1 (2010) | 2010–present |

| Savannah Storm | Basketball | East Coast Basketball League | Savannah High School | 2014–present | |

| Savannah Steam | American football | American Indoor Football | Tiger Arena | 2015–present |

College teams

| Club | Affiliation | Conference | Venues | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armstrong State Pirates | NCAA Division II | Peach Belt Conference | Alumni Arena | |

| Savannah College of Art and Design Bees | NAIA | Florida Sun Conference | SCAD Athletic Complex, Ronald C. Waranch Equestrian Center | |

| Savannah State Tigers | NCAA Division I (FCS) | MEAC | Tiger Arena, Ted Wright Stadium |

Sports facilities

|

Baseball |

Basketball Hockey |

Football

|

Education

Savannah has four colleges and universities offering bachelor's, master's, and professional or doctoral degree programs: Armstrong State University, Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), Savannah State University, and South University. In addition, Georgia Tech Savannah offers certificate programs, and Georgia Southern University has a satellite campus in the downtown area. Savannah Technical College, a two-year technical institution and the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, a marine science research institute of the University of Georgia located on the northern end of Skidaway Island, offer educational programs as well. Savannah is also the location of Ralston College, a liberal arts college founded in 2010.[70]

Mercer University began a four-year doctor of medicine program in August 2008 at Memorial University Medical Center. Mercer, with its main campus in Macon, received additional state funding in 2007 to expand its existing partnership with Memorial by establishing a four-year medical school in Savannah (the first in southern Georgia). Third- and fourth-year Mercer students have completed two-year clinical rotations at Memorial since 1996; approximately 100 residents are trained each year in a number of specialities. The expanded program opened in August 2008 with 30 first-year students.

In 2012, Savannah Law School opened in the historic Candler building on Forsyth Park. The school is fully ABA-accredited and offers full-time as well as part-time programs leading to the juris doctor degree.[71]

Savannah is also home to most of the schools in the Chatham County school district, the Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools.

Notable secondary schools in Savannah-Chatham County include the following. (Public schools are indicated with an asterisk.)

- Beach High School*

- Benedictine Military School

- Calvary Day School

- Groves High School*

- Islands High School*

- Jenkins High School*

- Johnson High School*

- New Hampstead High School*

- Saint Andrew's School

- St. Vincent's Academy

- Savannah Arts Academy*

- Savannah Christian Preparatory School

- Savannah Country Day School

- Savannah High School*

- Windsor Forest High School*

Oatland Island Wildlife Center of Savannah [b] is also a part of Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools. An environmental education center, it serves thousands of students from schools throughout the Southeastern United States. Located east of Savannah on a marsh island, it features a 2-mile (3.2 km) Native Animal Nature Trail that winds through maritime forest, salt marsh, and freshwater wetlands. Along the trail, visitors can observe native animals, such as Florida panthers, Eastern timber wolves, and alligators in their natural habitat.

Media

Savannah's major television stations are WSAV, channel 3 (NBC); WTOC-TV, channel 11 (CBS); WJCL, channel 22 (ABC); and WTGS, channel 28 (Fox). Two PBS member stations serve the city: WVAN (channel 9), part of Georgia Public Broadcasting; and WJWJ-TV (channel 16), part of SCETV.

Other stations include WGSA, channel 35 (The CW); and WXSX-CA, channel 46 (MTV2).

The Savannah Morning News is Savannah's only daily newspaper. The Savannah Tribune and the Savannah Herald are weekly newspapers with a focus on Savannah's African American community. Connect Savannah is an alternative free weekly newspaper focused on local news, culture and music.[72][73]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport is located off Interstate 95 west of Savannah. Airlines serving this airport are Delta, Delta Connection, JetBlue, United Express, US Airways, Vision Airlines and American Eagle. Until September 2008, DayJet provided on-demand air transportation service between Savannah and cities throughout the Southeast.

Amtrak operates a passenger terminal at Savannah for the Palmetto and Silver Service trains running between New York City and Miami, Florida with three southbound and three northbound trains stopping at the station daily.

Public transit throughout the region is provided by Chatham Area Transit.

The DOT (Downtown Transportation) system provides fare free transportation in the Historic District.[74] Services include express shuttle buses, the River Street Streetcar, and a ferry to Hutchinson Island and the Savannah International Trade and Convention Center.[74]

Interstates and major highways

Interstate 95 — Runs north-south just west of the city; provides access to Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport and intersects with Interstate 16, which leads into the city's center.

Interstate 95 — Runs north-south just west of the city; provides access to Savannah/Hilton Head International Airport and intersects with Interstate 16, which leads into the city's center. Interstate 16 — Terminates in downtown Savannah at Liberty and Montgomery streets, and intersects with Interstate 95 and Interstate 516.

Interstate 16 — Terminates in downtown Savannah at Liberty and Montgomery streets, and intersects with Interstate 95 and Interstate 516. Interstate 516 — An urban perimeter highway connecting southside Savannah, at DeRenne Avenue, with the industrialized port area of the city to the north; intersects with the Veterans Parkway and Interstate 16 as well. Also known as Lynes Parkway.

Interstate 516 — An urban perimeter highway connecting southside Savannah, at DeRenne Avenue, with the industrialized port area of the city to the north; intersects with the Veterans Parkway and Interstate 16 as well. Also known as Lynes Parkway. U.S. Route 80 (Victory Drive) — Runs east-west through midtown Savannah and connects the city with the town of Thunderbolt and the islands of Whitemarsh, Talahi, Wilmington and Tybee. Merges with the Islands Expressway and serves as the only means of reaching the Atlantic Ocean by automobile.

U.S. Route 80 (Victory Drive) — Runs east-west through midtown Savannah and connects the city with the town of Thunderbolt and the islands of Whitemarsh, Talahi, Wilmington and Tybee. Merges with the Islands Expressway and serves as the only means of reaching the Atlantic Ocean by automobile. U.S. Route 17 (Ocean Highway) — Runs north-south from Richmond Hill, through southside Savannah, into Garden City, back into west Savannah with a spur onto I-516, then I-16, and finally continuing over the Talmadge Memorial Bridge into South Carolina.

U.S. Route 17 (Ocean Highway) — Runs north-south from Richmond Hill, through southside Savannah, into Garden City, back into west Savannah with a spur onto I-516, then I-16, and finally continuing over the Talmadge Memorial Bridge into South Carolina. State Route 204 (Abercorn Expressway) — An extension of Abercorn Street that begins at 37th Street in midtown (which is its northern point) and terminates at Rio Road and the Forest River at its southern point, and serves as the primary traffic and commercial artery linking downtown, midtown and southside sections of the city.

State Route 204 (Abercorn Expressway) — An extension of Abercorn Street that begins at 37th Street in midtown (which is its northern point) and terminates at Rio Road and the Forest River at its southern point, and serves as the primary traffic and commercial artery linking downtown, midtown and southside sections of the city.- Harry S. Truman Parkway — Runs through eastside Savannah, connecting the east end of downtown with southside neighborhoods. Construction began in 1990 and opened in phases (the last phase, connecting with Abercorn Street, was completed in 2014).

- Veterans Parkway — Links Interstate 516 and southside/midtown Savannah with southside Savannah, and is intended to move traffic quicker from north-south by avoiding high-volume Abercorn Street. Also known as the Southwest Bypass.

- Islands Expressway — An extension of President Street to facilitate traffic moving between downtown Savannah, the barrier islands and the beaches of Tybee Island.

Crime

The total number of violent crimes in the Savannah-Chatham County reporting area ran just above 1,000 per year from 2003 through 2006. In 2007, however, the total number of violent crimes jumped to 1,163. Savannah-Chatham has recorded between 20 and 25 homicides each year since 2005.

In 2007, Savannah-Chatham recorded a sharp increase in home burglaries but a sharp decrease in larcenies from parked automobiles. During the same year, statistics show a 29 percent increase in arrests for Part 1 crimes. [75]

An additional increase in burglaries occurred in 2008 with 2,429 residential burglaries reported to Savannah-Chatham police that year. That reflects an increase of 668 incidents from 2007. In 2007, there were 1,761 burglaries, according to metro police data. [76]

Savannah-Chatham police report that crimes reported in 2009 came in down 6 percent from 2008.

In 2009, 11,782 crimes were reported to metro police — 753 fewer than in 2008. Within that 2009 number is a 12.2 percent decrease in violent crimes when compared with 2008. Property crimes saw a 5.3 percent decline, which included a 5.2 percent reduction in residential burglary. In 2008, residential burglary was up by almost 40 percent. While some violent crimes increased in 2009, crimes like street robbery went down significantly. In 2009, 30 homicides were reported, four more than the year before. Also, 46 rapes were reported, nine more than the year before. In the meantime, street robbery decreased by 23 percent. In 2008, metro police achieved a 90 percent clearance rate for homicide cases, which was described as exceptional by violent crimes unit supervisors. In 2009, the department had a clearance rate of 53 percent, which police attributed to outstanding warrants and grand jury presentations.[77]

The SCMPD provide the public with up to date crime report information through an online mapping service. This information can be found at[78]

So far, 2015 has seen a dramatic increase in the number of violent crimes, including at least fifty-four deaths due to gun violence, a number not seen since the early nineties.[79]

Sister cities

Savannah has five sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[80]

See also

- List of mayors of Savannah, Georgia

- List of people from Savannah, Georgia

- List of tallest buildings in Savannah

- Savannah, Georgia in popular culture

Notes

- ^ Savannah had 24 original squares. Today, 22 are still in existence. See Squares of Savannah, Georgia for additional information.

- ^ Oatland Island Wildlife Center of Savannah was named the Oatland Island Education Center until a name change in 2007.

References

- ^ [1] Archived 2015-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ a b c d "Savannah". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press. 2006-09-11. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ "Savannah", in The Concise Columbia Encyclopedia (Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 779.

- ^ "Savannah Information". Savannah Area Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ O.S. February 1, 1732, according to the Julian calendar used in the British colonies until September 2, 1752. With the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, eleven days in the date were omitted and the modern New Year (January 1) replaced the Julian contemporary New Year (March 25), previously observed in England and Wales.

- ^ a b Savannah from the New Georgia Encyclopedia Online

- ^ "Siege of Savannah During the American Revolutionary War". History Net: Where History Comes Alive - World & US History Online. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Jacqueline Jones, Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War (New York: Alfred Knopf, 2008), 206.

- ^ Cashin, Edward J. (1986). Colonial Augusta: "Key of the Indian Countrey". Mercer University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-86554-217-4.

- ^ "Shawnee", in Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., 1145

- ^ "Savannah River Basin" (PDF). Georgia River Network.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- ^ Names in South Carolina, Volume 22, Institute for Southern Studies. Archived 2014-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Names in South Carolina, Volume 16, Institute for Southern Studies. Archived 2014-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Part 1: Visit to Savannah". Georgiainfo.galileo.usg.edu. 1996-04-29. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ "Average Weather for Savannah, GA – Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

NOAAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map".

- ^ "Weather History for Savannah, GA [Georgia] for January". Weather-warehouse.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ Roger Beall. "Chatham County-Savannah Metropolitan Planning Commission". Thempc.org. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". census.gov.

- ^ "Metropolitan Area Population & Housing Patterns: 2000-2010".

- ^ [3]

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts: Savannah (city), Georgia".

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 22, 2012.

- ^ a b "City Government". City of Savannah. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "City of Savannah Neighborhoods 2008" (PDF). City of Savannah. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Coastal State Prison". Georgia Department of Corrections. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ "Agriculture in Georgia: Overview". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ^ Bloome, Kenneth J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Maritime Industry. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. p. 429. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "North American Container Traffic" (PDF). CMS Plus. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ "Savannah Book Festival". Savannahbookfestival.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "flannery-home". flannery-home.

- ^ "Flannery O'Connor Childhood Home". Flanneryoconnorhome.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Ballet Theatre". Savannahballettheatre.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "The Coastal Jazz Association". Coastal-jazz.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Children's Choir". Savannahchoir.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Concert Association". Savannahconcertassociation.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "The Savannah Orchestra". Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Savannah Philharmonic". Savannahphilharmonic.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "The Savannah Winds". Finearts.armstrong.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "The Armstrong Atlantic Youth Orchestra". Savaayo.org. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ a b Peisner, David (2009-11-09). "Metal in the Garden of Good and Evil". Spin.com. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ "Muse Arts Warehouse". Musesavannah.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Children's Theatre". Savannahchildrenstheatre.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Community Theatre". Savannahcommunitytheatre.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Little Theatre of Savannah". Littletheatreofsavannah.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Savannah Theatre". Savannahtheatre.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "City of Savannah Home Page". Archived from the original on August 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Savannah". City of Savannah. Archived from the original on March 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Savannah, the Forest City". N-georgia.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Visit Savannah". Savannah Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "America's Favorite Cities 2011 - Quality of Life and Visitor Experience | Travel + Leisure". Travelandleisure.com. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ "America's Favorite Cities 2011 - Savannah | Travel + Leisure". Travelandleisure.com. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ "America's Favorite Cities 2011 - Quality of Life and Visitor Experience - Architecture/Cool buildings | Travel + Leisure". Travelandleisure.com. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ "Tour Savannah's Squares". Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Squares of Savannah". Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ "City celebrates Whitaker Street garage; next phase at Ellis Square". Savannahnow.com. Savannah Morning News and Evening Press. 2009-01-23. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "First African Baptist Church of Savannah". PBS. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ [4] Archived 2014-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Eric N. DeLony (February 15, 1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Central of Georgia Railroad: Savannah Shops & Terminal Facilities" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-21. (includes 7 pages of drawings) and Template:PDFlink

- ^ "Georgia Historical Markers". University of Georgia Carl Vinson Institute of Government. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-04-10. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places". Archived from the original on April 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Club One". Clubone-online.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Ralston College". Ralston.ac. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Accreditation". Savannahlawschool.org. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Connect Savannah website". Connectsavannah.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ "Mondo Times entry on Connect Savannah". Mondotimes.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Your Savannah Resource for Downtown Transportation". Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ "City of Savannah Town Hall Report 02/08" (PDF). City of Savannah. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sarkissian, Arek (2009-02-04). "Burglaries soar in '08 for metro Savannah". Savannahnow.com. Savannah Morning News and Evening Press. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Sarkissian, Arek. "2010-01-22". Savannahnow.com. Savannah Morning News and Evening Press. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Savannah-Chatham Metropolitan Police Department". Scmpd.org. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ "SCMPD addresses violent crime concerns". www.wtoc.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ "Sister City US Listings – Directory Search Results". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Batumi - Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Batumi City Hall. Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

Further reading

- Coffey, Tom (1997). Savannah Lore and More. Savannah, Ga: Frederic C. Beil Pub. ISBN 0-913720-92-5. OCLC 37238907.

- Dick, Susan (2001). Savannah, Georgia. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 0-7385-0688-5. OCLC 47253807.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Elmore, Charles (2002). Savannah, Georgia. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 0-7385-1408-X. OCLC 54852532.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Russell, Preston, and Barbara Hines (1992). Savannah: A History of Her People Since 1733. Savannah, GA: Frederic C. Beil Pub. ISBN 0-913720-80-1. OCLC 613303710.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith, Derek (1997). Civil War Savannah. Savannah, GA: Frederic C. Beil Pub. ISBN 0-913720-93-3. OCLC 37221004.

External links

- www.savannahga.gov — Official City Web site

- www.visitsavannah.com — Official Site of the Savannah Convention & Visitors Bureau

- www.seda.org — Savannah Economic Development Authority

- Savannah Historic Newspapers Archive — Digital Library of Georgia

- Savannah Forum

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Savannah, Georgia

- Cities in Georgia (U.S. state)

- County seats in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Former state capitals in the United States

- Populated coastal places in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Populated places established in 1733

- Cities in Chatham County, Georgia

- Port cities and towns of the United States Atlantic coast

- Savannah metropolitan area