Spanish Colonial architecture

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

Spanish Colonial architecture represents Spanish colonial influence on New World and East Indies cities and towns, and it is still being seen in the architecture as well as in the city planning aspects of conserved present-day cities. These two visible aspects of the city are connected and complementary. The 16th century Laws of the Indies included provisions for the layout of new colonial settlements in the Americas and elsewhere.

To achieve the desired effect of inspiring awe among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas-Indians as well as creating a legible and militarily manageable landscape, the early colonizers used and placed the new architecture within planned townscapes and mission compounds.

The new churches and mission stations, for example, aimed for maximum effect in terms of their imposition and domination of the surrounding buildings or countryside. In order for that to be achievable, they had to be strategically located - at the center of a town square (plaza) or at a higher point in the landscape.

The Spanish Colonial style of architecture dominated in the early Spanish colonies of North and South America, and were also somewhat visible in its other colonies. It is sometimes marked by the contrast between the simple, solid construction demanded by the new environment and the Baroque ornamentation exported from Spain.

Mexico, as the center of New Spain - and the richest province of Spain's colonial empire - has some of the most renowned buildings built in this style. With twenty-nine sites, Mexico has more sites on the UNESCO World Heritage list than any other country in the Americas, many of them boasting some of the richest Spanish Colonial architecture. Some of the most famous cities in Mexico built in the Colonial style are Puebla, Zacatecas, Querétaro, Guanajuato, and Morelia.

The historic center of Mexico City is a mixture of architectural styles from the 16th century to the present. The Metropolitan Cathedral – built from 1563 to 1813 in a variety of styles including the Renaissance, Baroque, and Neo Classical. The rich interior is mostly Baroque. Other examples are the Palacio Nacional, the beautifully restored 18th-century Palacio de Iturbide, the 16th-century Casa de los Azulejos - clad with 18th-century blue-and-white talavera tiles, and many more churches, cathedrals, museums, and palaces of the elite.

During the late 17th century to 1750, one of Mexico's most popular architectural styles was Mexican Churrigueresque. These buildings were built in an ultra-Baroque, fantastically extravagant and visually frenetic style.

Antigua Guatemala in Guatemala is also known for its well preserved Spanish colonial style architecture. The city of Antigua is famous for its well-preserved Spanish Mudéjar-influenced Baroque architecture as well as a number of spectacular ruins of colonial churches dating from the 16th century. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Ciudad Colonial (colonial city) of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, founded in 1498, is the oldest city in the New World and a prime example of this architectural style. The port of Cartagena, Colombia, founded in 1533 and Santa Ana de Coro, Venezuela, founded in 1527, are two more UNESCO World Heritage Sites preserving some of the best Spanish colonial architecture in the Caribbean." San Juan was founded by the Spaniards in 1521, where Spanish colonial architecture can be found like the Historic Hotel El Convento.[1] Also, Old San Juan with its walled city and buildings (ranging from 1521 to the early 20th century) are very good examples, and in excellent condition.

According to UNESCO, Quito, Ecuador has the largest, best-preserved, and least-altered historic centre (320 hectares) in Latin America, despite several earthquakes. It was the first city that was inscribed onto the UNESCO World Heritage List, along with Kraków, Poland in 1978. The historic district of this city is the sole largest and best preserved area of Spanish Colonial architecture in the world.

History of the city grid in the New World

The idea of laying out a city in a grid pattern is not unique to the Spanish. In fact, it never started out with the Spanish colonizers. It has been traced back to some ancient civilizations especially the ancient cities of the Aztec and Maya, and also Ancient Greeks.[2] The idea was spread by the Roman conquest of European empires and its ideas were adopted by other civilizations. It was popularized at different paces and in different levels throughout the Renaissance - the French took to building grid-like villages (ville-neuves) and the English, under King Edward I did as well. Some argue, however, that Spain was not part of this movement to order towns as grids. Despite its clear military advantage, and despite the knowledge of city planning, the New World settlements of the Spanish actually grew amorphously for some three to four decades before they turned to grids and city plans as ways of organizing space. In contrast to the orders given much later on how the city should be laid out, Ferdinand II did not give specific instructions for how to build the new settlements in the Caribbeans. To Nicolas De Ovando, he said the following in 1501:

- As it is necessary in the island of Española to make settlements and from here it is not possible to give precise instructions, investigate the possible sites, and in conformity with the quality of the land and sites as well as with the present population outside present settlements establish settlements in the numbers and in the places that seem proper to you.[3]

City planning: a royal ordinance

In 1513 the monarchs wrote out a set of guidelines that ordained the conduct of Spaniards in the New World as well as that of the Indians that they found there. With regards to city planning, these ordinances had details on the preferred location of a new town and its location relative to the sea, mountains and rivers. It also detailed the shape and measurements of the central plaza taking into account the spacing for purposes of trade as well as the spacing for purposes of festivities or even military operations - occasions that involved horse-riding. In addition to specifying the location of the church, the orientation of roads that run into the main plaza as well as the width of the street with respect to climatic conditions, the guidelines also specified the order in which the city must be built.

- The building lots and the structures erected thereon are to be so situated that in the living rooms one can enjoy air from the south and from the north, which are the best. All town homes are to be so planned that they can serve as a defense or fortress against those who might attempt to create disturbances or occupy the town. Each house is to be so constructed that horses and household animals can be kept therein, the courtyards and stockyards being as large as possible to insure health and cleanliness.[4]

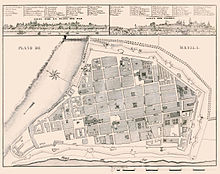

La Traza

The traza or layout was the pattern on which Spanish American cities were built beginning in the colonial era. At the heart of Spanish colonial cities was a central plaza, with the main church, town council (cabildo) building, residences of the main civil and religious officials, and the residences of the most important residents (vecinos) of the town built there. The principal businesses were also located around this central plan. Radiated from the main square were streets in at right angles, a grid that could extend as the settlement grew, impeded only by geography.[5] About three decades into colonization of the New World, the conquistadores started to build and plan cities according to laws prescribed by the monarchs in the Laws of the Indies. In addition to describing other aspects of the interactions between the Spanish conquerors and the natives they encountered, these laws ordained the specific ways new settlements should be laid out. In addition to specifying the layout, the laws also required a pattern in settlement based on social standing, in which the people of higher social status lived closer to the center of the town, the center of political, ecclesiastical, and economic power. The 1790 census for Mexico City indicates that in the traza that there was indeed a higher concentration of Spaniards (españoles), but that there was no absolute racial or class segregation in the city, particularly since elite households usually had non-white servants.[6]

The grid was not limited to Spanish settlements; however, "Reducciones" Indian Reductions and "Congregaciones" were created in a similar grid-like manner for Indians in order to organize these populations in more manageable units for purposes of taxation, military efficiency and in order to teach Indians the way of the Spanish.

Modern cities in Latin America have grown, and consequently erased or jumbled the previous standard spatial and social organization of the cityscape. Elites do not always live closer to the city center, and the point-space occupied by individuals is not necessarily determined by their social status. The central plaza, the wide streets and a grid pattern are still common elements in Mexico City and Puebla de Los Angeles. It is not uncommon in modern-founded towns, especially those in remote areas of Latin America, to have retained the “checkerboard layout” even to present day.

Mexico City is a good example of how these ordinances were followed in laying out a city. Previously the capital of the Aztec empire, Tenochtitlan was captured and placed under Spanish rule in 1521. After news of the conquest, the king sent instructions very similar to the aforementioned Ordinance of 1513. In some parts the instructions are almost verbatim to his previous ones. The instructions were meant to direct the conqueror —Hernán Cortés—on how to lay out the city and how to allocate land to the Spaniards. It is pointed out, however, that though the king might have sent many such orders and instructions to other conquistadores, Cortés was perhaps the first one to implement them. He insisted on carrying out the building of a new city where the Indian Empire had stood, and he incorporated features of the old plaza into the new grid. Much was accomplished since he was accompanied by men familiar with the grid system and the royal instructions. The point here is that Cortés accomplished the planning and was on his way to finish the building of Mexico City before the royal ordinances addressed specifically to him even arrived. Men like Cortés and Alonso García Bravo (who is also called “the good geometer”),[citation needed] played a crucial role in creating a city scape of New World cities as we know them.

Church and mission architecture

In places of dense indigenous settlement, such as in Central Mexico, the mendicant orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, and Augustinians) built churches on the sites of prehispanic temples. In the early period of the "spiritual conquest", there were so many indigenous neophytes who attended Mass that a large open-air atrium was built, walling off a space within the church complex to create an enlarged sacred space without great expense of building.[7] Indigenous labor was used in construction; since a communities sacred place was a symbol and embodiment of that community, laboring to create these structures was not necessarily an unwanted burden. Since Mexico experienced many sixteenth-century epidemics that drastically the size of the central Mexican indigenous population, there were often elaborate churches with few Indians still living to attend them, such as the Augustinian church at Acolman, Mexico. The different mendicant orders had distinct styles of building. Franciscans built large churches to accommodate the new neophytes, Dominican churches were highly ornamented, while the Augustinian churches were characterized by their critics as opulent and sumptuous.[8]

Mission churches were often of simple design. As mendicants were pushed out of central Mexico and as Jesuits also evangelized Indians in northern Mexico, they built mission churches as part of a larger complex, with living quarters and workshops for resident Indians. Unlike central Mexico, where churches were built in existing indigenous towns, on the frontier where indigenous did not live in such settlements, the mission complex was created.[9]

Gallery

-

The Cathedral of Santa María la Menor in Santo Domingo

-

The Cathedral in Mexico City

-

São Miguel das Missões, Brazil

-

The Cathedral of Havana

-

Street in Trinidad

-

Torre Tagle Palace, Lima

-

Church of San Francisco, Quito

-

Casa de la moneda, Potosí

-

Castillo de San Marcos, Florida

-

La Merced Church, Antigua Guatemala

-

Alamo Mission in Texas

-

Basilica of Saint Martin of Tours, Philippines

-

Palace of the Governors, Santa Fe, New Mexico

-

Concepción Mission, Bolivia

-

Compañía de Jesús, Panama

-

Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, Oaxaca

See also

- History of Mexico City

- Churrigueresque

- Spanish Baroque architecture - evolved in Spain and its colonies circa 17th century.

- The Baroque and colonialism

- Spanish architecture

- Spanish Colonial Revival Style architecture

- Mission Revival Style architecture

- Mediterranean Revival architecture

References

- ^ "Hotel El Convento: Making Over a Nunnery". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Stanislawski, Dan (Jan 1946). "The Origin and Spread of the Grid-Pattern Town". 36 (1). JSTOR 211076.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Stanislawki, Dan (Jan 1947). "Early Spanish Town Planning in the New World". Geographical Review. 37 (1). JSTOR 211364.

- ^ Nuttall, Zelia (May 1922). "Royal Ordinances Concerning the Laying Out of New Towns". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 5 (2): 249–254. doi:10.2307/2506027.

- ^ James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz, Early Latin America, New York: Cambridge University Press, 66-68.

- ^ Dennis Nodin Valdés, "The Decline of the Sociedad de Castas in Mexico City." PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan 1978.

- ^ John McAndrew, The Open Air Churches of Sixteenth-century Mexico: Atrios, posas, open chapels and other studies, Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1965.

- ^ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico. Pearson, 2003, p. 119.

- ^ Altman, et al., Early History of Greater Mexico, pp. 130-31.