Substitution reaction

Substitution reaction (also known as single displacement reaction or single replacement reaction) is a chemical reaction during which one functional group in a chemical compound is replaced by another functional group.[1][2] Substitution reactions are of prime importance in organic chemistry. Substitution reactions in organic chemistry are classified either as electrophilic or nucleophilic depending upon the reagent involved. There are other classifications as well that are mentioned below.

Organic substitution reactions are classified in several main organic reaction types depending on whether the reagent that brings about the substitution is considered an electrophile or a nucleophile, whether a reactive intermediate involved in the reaction is a carbocation, a carbanion or a free radical or whether the substrate is aliphatic or aromatic. Detailed understanding of a reaction type helps to predict the product outcome in a reaction. It also is helpful for optimizing a reaction with regard to variables such as temperature and choice of solvent.

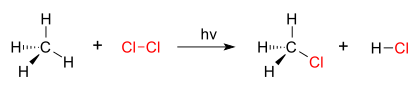

A good example of a substitution reaction is halogenation. When chlorine gas (Cl-Cl) is irradiated, some of the molecules are split into two chlorine radicals (Cl.) whose free electrons are strongly nucleophilic. One of them breaks a weak C-H covalent bond and grabs the liberated proton to form the electrically neutral H-Cl. The other radical reforms a covalent bond with the CH3. to form CH3Cl (methyl chloride).

| chlorination of methane by chlorine |

|---|

Nucleophilic substitution

In organic (and inorganic) chemistry, nucleophilic substitution is a fundamental class of reactions in which a nucleophile selectively bonds with or attacks the positive or partially positive charge on an atom or a group of atoms. As it does so, it replaces a weaker nucleophile which then becomes a leaving group; The remaining positive or partially positive atom becomes an electrophile. The whole molecular entity of which the electrophile and the leaving group are part is usually called the substrate.[1][2]

The most general form for the reaction may be given as where R-LG indicates the substrate.

- Nuc: + R-LG → R-Nuc + LG:

The electron pair (:) from the nucleophile (Nuc:) attacks the substrate (R-LG) forming a new covalent bond Nuc-R-LG. The prior state of charge is restored when the leaving group (LG) departs with an electron pair. The principal product in this case is R-Nuc. In such reactions, the nucleophile is usually electrically neutral or negatively charged, whereas the substrate is typically neutral or positively charged.

An example of nucleophilic substitution is the hydrolysis of an alkyl bromide, R-Br, under basic conditions, where the attacking nucleophile is the base OH− and the leaving group is Br−.

- R-Br + OH− → R-OH + Br−

Nucleophilic substitution reactions are commonplace in organic chemistry, and they can be broadly categorized as taking place at a carbon of a saturated aliphatic compound carbon or (less often) at an aromatic or other unsaturated carbon center.[3]

Mechanisms

These substitutions can be produced by two different mechanisms categorized at: unimolecular nucleophilic substitution (SN1) and bimolecular nucleophilic substitution (SN2).

The SN1 mechanism has two steps. In the first step, the leaving group departs, forming a carbocation C+. In the second step, the nucleophilic reagent (Nuc:) attaches to the carbocation and forms a covalent sigma bond. If the substrate has a chiral carbon, this mechanism can result in either inversion of the stereochemistry or retention of configuration. Usually both occur without preference. The result is racemization.

For an example with diagrams see the reaction of tert-butyl bromide with water shown at SN1 reaction.

The SN2 mechanism have just one step. The attack of the reagent and the expulsion of the leaving group happen simultaneously. This mechanism always results in inversion of configuration.

If the substrate that is under nucleophilic attack is chiral, the reaction will lead to an inversion of its stereochemistry called a Walden inversion.

For the example of SN2 reaction of chloroethane with bromide ion see SN2 reaction.

SN2 attack may occur if the backside route of attack is not sterically hindered by substituents on the substrate. Therefore, this mechanism usually occurs at an unhindered primary carbon center. If there is steric crowding on the substrate near the leaving group, such as at a tertiary carbon center, the substitution will involve an SN1 rather than an SN2 mechanism, (an SN1 would also be more likely in this case because a sufficiently stable carbocation intermediary could be formed).

When the substrate is an aromatic compound the reaction type is nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Carboxylic acid derivatives react with nucleophiles in nucleophilic acyl substitution. This kind of reaction can be useful in preparing compounds.

Electrophilic substitution

Electrophiles are involved in electrophilic substitution reactions, particularly in electrophilic aromatic substitutions.

In this example the benzene ring's electron resonance structure is attacked by an electrophile E+. The resonating bond is broken and a carbocation resonating structure results. Finally a proton is kicked out and a new aromatic compound is formed.

| Electrophilic aromatic substitution |

|---|

Electrophilic reactions to other unsaturated compounds than arenes generally lead to electrophilic addition rather than substitution.

Radical substitution

A radical substitution reaction involves radicals. An example is the Hunsdiecker reaction.

Organometallic substitution

Coupling reactions are a class of metal-catalyzed reactions involving an organometallic compound RM and an organic halide R'X that together react to form a compound of the type R-R' with formation of a new carbon-carbon bond. Examples include the Heck reaction, Ullmann reaction, and Wurtz–Fittig reaction. Many variations exist.[3]

Substituted compounds

Substituted compounds are chemical compounds where one or more hydrogen atoms of a core structure have been replaced with a functional group like alkyl, hydroxy, or halogen, or with larger substituent groups.

For example, benzene is a simple aromatic ring. Benzenes that have undergone substitution are a heterogeneous group of chemicals with a wide spectrum of uses and properties:

| Examples of substituted benzene compounds | ||

| compound | general formula | general structure |

| Benzene | C6H6 |  |

| Toluene | C6H5-CH3 | |

| o-Xylene | C6H4(-CH3)2 |  |

| Mesitylene | C6H3(-CH3)3 |  |

| Phenol | C6H5-OH |  |

References

- ^ March, Jerry (1985), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure, 3rd edition, New York: Wiley, ISBN 9780471854722, OCLC 642506595

- ^ Imyanitov, Naum S. (1993). "Is This Reaction a Substitution, Oxidation-Reduction, or Transfer?". J. Chem. Educ. 70 (1): 14–16. Bibcode:1993JChEd..70...14I. doi:10.1021/ed070p14.

- ^ Elschenbroich, C.; Salzer, A. (1992). Organometallics: A Concise Introduction (2nd ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-28165-7.