Tarim mummies

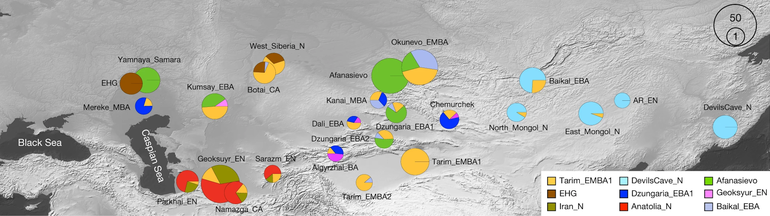

Location of the Tarim mummies ( ), with other contemporary cultures c. 2000 BCE

| |

| Geographical range | Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 2100 BCE – 1 BCE |

| Preceded by | Afanasievo culture |

| Followed by | Tocharians |

The Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, which date from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE,[1][2][3] with a new group of individuals recently dated to between c. 2100 and 1700 BCE.[4][5] The Tarim population to which the earliest mummies belonged was agropastoral, and they lived c. 2000 BCE in what was formerly a freshwater environment, which has now become desertified.[6]

A genomic study published in 2021 found that these early mummies (dating from 2,135 to 1,623 BCE) had high levels of Ancient North Eurasian ancestry (ANE, about 72%), with smaller admixture from Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA, about 28%), but no detectable Western Steppe-related ancestry.[7][8] They formed a genetically isolated local population that "adopted neighbouring pastoralist and agriculturalist practices, which allowed them to settle and thrive along the shifting riverine oases of the Taklamakan Desert."[9] These mummified individuals were long suspected to have been "Proto-Tocharian-speaking pastoralists", ancestors of the Tocharians, but this has now been largely discredited by their absence of a genetic connection with Indo-European-speaking migrants, particularly the Afanasievo or BMAC cultures.[10]

Later Tarim Mummies dated to the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), such as those of the Subeshi culture, have characteristics closely resembling those of the Saka (Scythian) Pazyryk culture of the Altai Mountains, in particular in the areas of weaponry, horse gear and garments.[11] They are candidates as the Iron Age predecessors of the Tocharians.[12] The rather recent easternmost mummies at Qumul (Yanbulaq culture, 1100–500 BCE), provide the earliest Asian mummies found in the Tarim Basin, and have a mix of "Europoid" and "Mongoloid" mummies.[13] [2]

Archaeological record

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, European explorers such as Sven Hedin, Albert von Le Coq and Sir Aurel Stein all recounted their discoveries of desiccated bodies in their search for antiquities in Central Asia.[14] Since then, numerous other mummies have been found and analyzed, many of them now displayed in the museums of Xinjiang. Most of these mummies were found on the eastern end of the Tarim Basin (around the area of Lopnur, Subeshi near Turpan, Loulan, Kumul), or along the southern edge of the Tarim Basin (Khotan, Niya, and Cherchen or Qiemo).

According to Mallory & Mair (2000), the earliest Tarim mummies, found at Qäwrighul (Gumugou) and dated to 2135–1939 BCE, were classified in a craniometric analysis as belonging to a "Proto-Europoid" type, whose closest affiliation is to the Bronze Age populations of southern Siberia, Kazakhstan, Central Asia, and the Lower Volga.[2] A revised craniometric analyses by Hemphill & Mallory (2004) on the early Tarim mummies (Qäwrighul) failed to demonstrate close phenetic affinities to "Europoid populations", but rather found that they formed their own cluster, distinct from the European-related Steppe pastoralists of the Andronovo and Afanasievo cultures, or the inhabitants of the Western Asian BMAC culture. Later Tarim mummies displayed varying affinities with Andronovo-like, BMAC-like or Han-like populations, suggesting different waves of migration into the Tarim basin.[15]

Notable mummies are the tall, red-haired "Chärchän man" or the "Ur-David" (1000 BCE); his son (1000 BCE), a 1-year-old baby with brown hair protruding from under a red and blue felt cap, with two stones positioned over its eyes; the "Hami Mummy" (c. 1400–800 BCE), a "red-headed beauty" found in Qizilchoqa; and the "Witches of Subeshi" (4th or 3rd century BCE), who wore 2-foot-long (0.61 m) black felt conical hats with a flat brim.[16] Also found at Subeshi was a man with traces of a surgical operation on his abdomen; the incision is sewn up with sutures made of horsehair.[17]

Many of the mummies have been found in very good condition, owing to the dryness of the desert and the desiccation it produced in the corpses. The mummies share many typical Caucasian body features, and many of them have their hair physically intact, ranging in color from blond to red to deep brown, and generally long, curly and braided. Their costumes, and especially textiles, may indicate a common origin with Indo-European neolithic clothing techniques or a common low-level textile technology. Chärchän man wore a red twill tunic and tartan leggings. Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber, who examined the tartan-style cloth, discusses similarities between it and fragments recovered from salt mines associated with the Hallstatt culture.[18] As a result of the arid conditions and exceptional preservation, tattoos have been identified on mummies from several sites around the Tarim Basin, including Qäwrighul, Yanghai, Shengjindian, Shanpula (Sampul), Zaghunluq, and Qizilchoqa.[19]

It has been asserted that the textiles found with the mummies are of an early European textile type based on close similarities to fragmentary textiles found in salt mines in Austria, dating from the second millennium BCE. Anthropologist Irene Good, a specialist in early Eurasian textiles, noted the woven diagonal twill pattern indicated the use of a rather sophisticated loom and said that the textile is "the easternmost known example of this kind of weaving technique".[17]

The cemetery at Yanbulaq contained 29 mummies which dated from 1100 to 500 BCE, 21 of which are Asian—the earliest Asian mummies found in the Tarim Basin—and eight of which are of the same Caucasian physical type as found at Qäwrighul.[2]

Genetic studies

[edit]

In 1995, Mair claimed that "the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucasoid, or Europoid" with east Asian migrants arriving in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin around 3,000 years ago while the Uyghur peoples arrived around the year 842. In trying to trace the origins of these populations, Victor Mair's team suggested that they may have arrived in the region by way of the Pamir Mountains about 5,000 years ago.

Mair has claimed that:

The new finds are also forcing a reexamination of old Chinese books that describe historical or legendary figures of great height, with deep-set blue or green eyes, long noses, full beards, and red or blond hair. Scholars have traditionally scoffed at these accounts, but it now seems that they may be accurate.[20]

In 2007, the Chinese government allowed a National Geographic Society team headed by Spencer Wells to examine the mummies' DNA. Wells was able to extract undegraded DNA from the internal tissues. The scientists extracted enough material to suggest the Tarim Basin was continually inhabited from 2000 BCE to 300 BCE and preliminary results indicate the people, rather than having a single origin, originated from Europe, Mesopotamia, Indus Valley and other regions yet to be determined.[21]

A 2008 study by Jilin University showed that the Yuansha population has relatively close relationships with the modern populations of South Central Asia and Indus Valley, as well as with the ancient population of Chawuhu.[22][23]

Between 2009 and 2015, the remains of 92 individuals found at the Xiaohe Tomb complex were analyzed for Y-DNA and mtDNA markers. Genetic analyses of the mummies showed that the maternal lineages of the Xiaohe people originated from both East Asia and West Eurasia, whereas the paternal lineages all originated from West Eurasia. The East Eurasian mtDNA carried by the Tarim mummies is mtDNA haplogroup C and the particular subclade found in the Tarim mummies originates from southeast Siberians like Udeghe and Evenks and not from East Asians, who carry mtDNA haplogroup C at a far lower rate and carry different subclades of mtDNA C.[21]

Mitochondrial DNA analysis showed that maternal lineages carried by the people at Xiaohe included mtDNA haplogroups H, K, U5, U7, U2e, T and R*, which are now most common in West Eurasia. Also found were haplogroups common in modern populations from East Asia: B5, D and G2a. Haplogroups now common in Central Asian or Siberian populations included: C4 and C5. Haplogroups later regarded as typically South Asian included M5 and M*.[23]

Li et al. (2010) found that nearly all – 11 out of 12 males, or around 92% – belonged to Y-DNA haplogroup R1a1a-M198,[24] which are now most common in Northern India and Eastern Europe; the remaining one belonged to the exceptionally rare paragroup K* (M9) from Asia.[25][26]

The geographic location of this admixing is unknown, although south Siberia is likely.[21]

Chinese historian Ji Xianlin says China "supported and admired" research by foreign experts into the mummies. "However, within China a small group of ethnic separatists have taken advantage of this opportunity to stir up trouble and are acting like buffoons. Some of them have even styled themselves the descendants of these ancient 'white people' with the aim of dividing the motherland. But these perverse acts will not succeed."[27] Barber addresses these claims by noting that "The Loulan Beauty is scarcely closer to 'Turkic' in her anthropological type than she is to Han Chinese. The body and facial forms associated with Turks and Mongols began to appear in the Tarim cemeteries only in the first millennium BCE, fifteen hundred years after this woman lived."[28] Due to the "fear of fuelling separatist currents", the Xinjiang museum, regardless of dating, displays all their mummies, both Tarim and Han, together.[27]

The School of Life Sciences, Jilin University, China, analyzed in 2021 13 individuals from the Tarim basin, dated to c. 2100–1700 BC, and assigned 2 to Y-haplogroup R1b1b-PH155/PH4796 (R1b1c in ISOGG2016), 1 – to Y-haplogroup R1-PF6136 (xR1a, xR1b1a).[4][29]

Derivation from Ancient North Eurasians

[edit]A 2021 genetic study on the Tarim mummies (13 mummies, including 11 from Xiaohe Cemetery, ranging from 2,135 to 1,623 BCE) found that they were most closely related to an earlier identified group called the Ancient North Eurasians, particularly the population represented by the Afontova Gora 3 specimen (AG3), genetically displaying "high affinity" with it.[30][31] The genetic profile of the Afontova Gora 3 individual represented about 72% of the ancestry of the Tarim mummies from Xiaohe, while the remaining 28% of their ancestry was derived from Ancient Northeast Asians (ANA, Early Bronze Age Baikal populations).[32] Tarim mummies from Beifang have a slightly higher amount of ANA ancestry and can be modelled as having 89% Xiaohe-like ancestry and about 11% ANA ancestry.[9] The Tarim mummies are thus one of the rare Holocene populations who derive most of their ancestry from the Ancient North Eurasians (ANE, specifically the Mal'ta and Afontova Gora populations), despite their distance in time (around 14,000 years).[33] More than any other ancient populations, the Tarim mummies can be considered as "the best representatives" of the Ancient North Eurasians.[33]

Tests on their genetic legacy also found that many groups in Central Asia and Xinjiang derive varying degrees of ancestry from a population related to the Tarim mummies. The Tajik people show the relative highest affinity with the Tarim mummies, although their main ancestry is linked to Bronze Age Steppe pastoralists (Western Steppe Herders).[34]

Posited origins

[edit]

Mallory and Mair (2000) propose the movement of at least two Caucasian physical types into the Tarim Basin. The authors associate these types with the Tocharian and Iranian (Saka) branches of the Indo-European language family, respectively.[37] However, archaeology and linguistics professor Elizabeth Wayland Barber cautions against assuming the mummies spoke Tocharian, noting a gap of about a thousand years between the mummies and the documented Tocharians: "people can change their language at will, without altering a single gene or freckle".[38]

On the other hand, linguistics professor Ronald Kim argues that the amount of divergence between the attested Tocharian languages necessitates that Proto-Tocharian must have preceded their attestation by a millennium or so. This would coincide with the timeframe during which the Tarim Basin culture was in the region.[39]

B.E. Hemphill's biodistance analysis of cranial metrics (as cited in Larsen 2002 and Schurr 2001) has questioned the identification of the Tarim Basin population as European, noting that the earlier population forms their own distinct cluster and having closer affinities to two specimens from the Harappan site of the Indus Valley civilisation, while the later Tarim population displays closer affinities with the Oxus River valley population. Because craniometry can produce results which make no sense at all (e.g. the close relationship between Neolithic populations in Ukraine and Portugal) [better source needed] and therefore lack any historical meaning, any putative genetic relationship must be consistent with geographical plausibility and have the support of other evidence.[40][41]

Han Kangxin, who examined the skulls of 302 mummies, found the closest relatives of the earlier Tarim Basin population in the populations of the Afanasevo culture situated immediately north of the Tarim Basin and the Andronovo culture that spanned Kazakhstan and reached southwards into West Central Asia and the Altai.[42]

It is the Afanasevo culture to which Mallory & Mair (2000:294–296, 314–318) trace the earliest Bronze Age settlers of the Tarim and Turpan basins. The Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BCE) displays cultural and genetic connections with the Indo-European-associated cultures of the Eurasian Steppe yet predates the specifically Indo-Iranian-associated Andronovo culture (c. 2000–900 BCE) enough to isolate the Tocharian languages from Indo-Iranian linguistic innovations like satemization.[43]

Mair concluded:

From the evidence available, we have found that during the first 1,000 years after the Loulan Beauty, the only settlers in the Tarim Basin were Caucasoid. East Asian peoples only began showing up in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin about 3,000 years ago, Mair said, while the Uighur peoples arrived after the collapse of the Orkon Uighur Kingdom, largely based in modern day Mongolia, around the year 842.[27]

Hemphill & Mallory (2004) note the existence of an additional physical type at Alwighul (700–1 BCE) and Krorän (200 CE) different from the earlier one found at Qäwrighul (1800 BCE) and Yanbulaq (1100–500 BCE), while finding no evidence of significant Steppe-related contributions to these remains:

The results fail to demonstrate close phenetic affinities between the early inhabitants of Qäwrighul and any of the proposed sources for immigrants to the Tarim Basin. The absence of close affinities to outside populations renders it unlikely that the human remains recovered from Qa¨wrighul represent the unadmixed remains of colonists from the Afanasievo or Andronovo cultures of the steppe lands, or inhabitants of the urban centers of the Oxus civilization of Bactria. ... This study confirms the assertion of Han [1998] that the occupants of Alwighul and Krorän are not derived from proto-European steppe populations, but share closest affinities with Eastern Mediterranean populations. Further, the results demonstrate that such Eastern Mediterraneans may also be found at the urban centers of the Oxus civilization located in the north Bactrian oasis to the west. Affinities are especially close between Krorän, the latest of the Xinjiang samples, and Sapalli, the earliest of the Bactrian samples, while Alwighul and later samples from Bactria exhibit more distant phenetic affinities. This pattern may reflect a possible major shift in interregional contacts in Central Asia in the early centuries of the second millennium BCE. ... Nevertheless, there is no support for the hypothesis that steppe populations contributed significantly to Bronze Age populations of the Tarim Basin. Despite numerous similarities between Afanasievo and Andronovo artifacts and Bronze Age artifacts from Xinjiang (Bunker, 1998; Chen and Hiebert, 1995; Kuzmina, 1998; Mei and Shell, 1998; Peng, 1998), all analyses of phenetic relationships consistently reveal a profound phenetic separation between steppe samples and the samples from the Tarim Basin (Qäwrighul, Alwighul, and Krorän).

Zhang et al. (2021) proposed that the 'Western' like features of the earlier Tarim mummies could be attributed to their Ancient North Eurasian ancestry.[44] Previous craniometric analyses on the early Tarim mummies found that they were forming a distinct cluster of their own, and neither clustered with European-related Steppe pastoralists from the Andronovo and Afanasievo culture, nor with inhabitants of the Western Asian BMAC culture, or East Asian populations further East.[45]

Historical records and associated texts

[edit]Chinese sources

[edit]

Western Regions (Hsi-yu; Chinese: 西域; pinyin: Xīyù; Wade–Giles: Hsi1-yü4) is the historical name in China, between the 3rd century BCE and 8th century CE for regions west of Yumen Pass, including the Tarim and Central Asia.[46]

Some of the peoples of the Western Regions were described in Chinese sources as having full beards, red or blond hair, deep-set blue or green eyes and high noses.[47] According to Chinese sources, the city states of the Tarim reached the height of their political power during the 3rd to 4th centuries CE,[48] although this may actually indicate an increase in Chinese involvement in the Tarim, following the collapse of the Kushan Empire.

The Rouzhi

[edit]Reference to the Rouzhi name was possibly made around 7th century BCE by the Chinese philosopher Guan Zhong, though his book is generally considered to be a later forgery.[49]: 115–127 Guan Zhong described a group called either the Yuzhi 禺氏 or Niuzhi 牛氏 as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains of Yuzhi 禺氏 at Gansu.

After the Rouzhi experienced a series of major defeats at the hands of the Xiongnu, during the 2nd century BCE, a group known as the Greater Rouzhi migrated to Bactria, where they established the Kushan Empire. By the 1st century CE, the Kushan Empire had expanded significantly and may have annexed part of the Tarim Basin.

Tocharian languages

[edit]

The degree of differentiation between the language known to modern scholars as Tocharian A (or by the endonym Ārśi-käntwa; "tongue of Ārśi") and Tocharian B (Kuśiññe; [adjective] "of Kucha, Kuchean"), as well as the less-well attested Tocharian C (which is associated with the city-state of Krorän, also known as Loulan), and the absence of evidence for these beyond the Tarim, tends to indicate that a common, proto-Tocharian language existed in the Tarim during the second half of the 1st millennium BCE. Tocharian is attested in documents between the 3rd and 9th centuries CE, although the first known epigraphic evidence dates to the 6th century CE.

Although the Tarim mummies preceded the Tocharian texts by around 2,000 years, their shared geographical location and links to Western Eurasia have led many scholars to suggest that the mummies were related to the Tocharian peoples.

Arguments for cultural transmission from West to East

[edit]The possible presence of speakers of Indo-European languages in the Tarim Basin by about 2000 BCE[37] could, if confirmed, be interpreted as evidence that cultural exchanges occurred among Indo-European and Chinese populations at a very early date. It has been suggested that such techniques as chariot warfare and bronze-making may have been transmitted to the east by these Indo-European nomads.[50] Mallory and Mair also note that: "Prior to c. 2000 BC, finds of metal artifacts in China are exceedingly few, simple and, puzzlingly, already made of alloyed copper (and hence questionable)."

While stressing that the argument as to whether bronze technology travelled from China to the West or that "the earliest bronze technology in China was stimulated by contacts with western steppe cultures", is far from settled in scholarly circles, they suggest that the evidence so far favours the latter scenario.[51] However, the culture and the technology in the northwest region of Tarim basin were less advanced than that in the East China of Yellow River-Erlitou (2070 BCE ~ 1600 BCE) or Majiayao culture (3100 BCE ~ 2600 BCE), the earliest bronze-using cultures in China, which implies that the northwest region did not use copper or any metal until bronze technology was introduced to the region by the Shang dynasty in about 1600 BC. The earliest bronze artifacts in China are found at the Majiayao site (between 3100 and 2700 BCE),[52][53] and it is from this location and time period that Chinese Bronze Age spread. Bronze metallurgy in China originated in what is referred to as the Erlitou (Wade–Giles: Erh-li-t'ou) period, which some historians argue places it within the range of dates controlled by the Shang dynasty.[54]

Others believe the Erlitou sites belong to the preceding Xia (Wade–Giles: Hsia) dynasty.[55] The US National Gallery of Art defines the Chinese Bronze Age as the "period between about 2000 BC and 771 BC," which begins with Erlitou culture and ends abruptly with the disintegration of Western Zhou rule.[56] Though that provides a concise frame of reference, it overlooks the continued importance of bronze in Chinese metallurgy and culture. Since that was significantly later than the discovery of bronze in Mesopotamia, bronze technology could have been imported, rather than being discovered independently in China. However, there is reason to believe that bronzework developed inside China, separately from outside influence.[57][58]

The Chinese official Zhang Qian, who visited Bactria and Sogdiana in 126 BCE, made the first known Chinese report on many regions west of China. He believed to have discerned Greek influences in some of the kingdoms. He named Parthia "Ānxī" (Chinese: 安息), a transcription of "Arshak" (Arsaces), the name of the founder of Parthian dynasty.[59] Zhang Qian clearly identified Parthia as an advanced urban civilization that farmed grain and grapes and manufactured silver coins and leather goods.[60] Zhang Qian equated Parthia's level of advancement to the cultures of Dayuan in Ferghana and Daxia in Bactria.

The supplying of Tarim Basin jade to China from ancient times is well established, according to Liu (2001): "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty by Zheng Zhenxiang, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BCE the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China."

Famous mummies

[edit]The Princess of Xiaohe

[edit]The Princess of Xiaohe (Chinese: 小河公主) was unearthed and also named by the archaeologists of Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology at Xiaohe Cemetery Tomb M11, 102 km west of Loulan, Nop Nur, Xinjiang in 2003.[61] She has red hair and long eyelashes and was wrapped in a white wool cloak with tassels and wore a felt hat, string skirt, and fur-lined leather boots. She was buried with wooden pins and three small pouches of ephedra and twigs and branches of ephedra were placed beside the body.[62] She is not permanently exhibited in any museum.

The Beauty of Loulan

[edit]The Beauty of Loulan (also referred to as the "Loulan Beauty" or the "Beauty of Krorän") is the most famous of the Tarim mummies, along with the Cherchen Man.[63] She was discovered in 1980 by Chinese archaeologists working on a film about the Silk Road. The mummy was discovered near Lop Nur. She was buried 3 feet beneath the ground. The mummy was extremely well preserved because of the dry climate and the preservative properties of salt.[64] She was wrapped in a woolen cloth; the cloth was made of two separate pieces and was not large enough to cover her entire body, thereby leaving her ankles exposed. The Beauty of Loulan was surrounded by funerary gifts.[65] The Beauty of Loulan has been dated back to approximately 1800 BCE.[66]

The Beauty of Loulan lived around 1800 BCE, until about the age of 45, when she died. Her cause of death is likely due to lung failure from ingesting a large amount of sand, charcoal, and dust.[64] According to Elizabeth Barber, she probably died in the winter because of her provisions against the cold.[65] The rough shape of her clothes and the lice in her hair suggest she lived a difficult life.[64]

The Beauty of Loulan's hair colour has been described as auburn.[65] Her hair was infested with lice.[64] The Beauty of Loulan is wearing clothing made of wool and fur. Her hood is made of felt and has a feather in it.[69] She is wearing rough ankle-high moccasins made of leather, with fur on the outside. Her skirt is made of leather, with fur on the inside for warmth. She is also wearing a woolen cap. According to Elizabeth Barber, these provisions against the cold suggest she died during the winter.[65] The Beauty of Loulan possesses a comb, with four teeth remaining. Barber suggests that this comb was a dual purpose tool to comb hair and to "pack the weft in tightly during weaving." She possesses a "neatly woven bag or soft basket". Grains of wheat were discovered inside the bag.[65]

A 23-poem sequence on the Beauty of Loulan appears in the Canadian poet Kim Trainor's Karyotype (2015).

Other mummies

[edit]-

Another "Loulan Beauty", excavated in 2004. Buried at the age of 25, she is 3800 years old

-

Mummy from Xiaohe cemetery

-

The "Cherchen Man", dated c. 1000 BCE

-

A wife of the "Cherchen Man", dated c. 1000 BCE

Yingpan man

[edit]

The Yingpan man is a much later mummy from the same area, dating to the 4th–5th century CE. Dressed in luxurious Hellenistic clothes, he may have been a Sogdian or an elite member of the Shanshan Kingdom.[70][71]

Controversies

[edit]According to Ed Wong's New York Times article from 2008, Mair was prohibited from leaving the country with 52 genetic samples. However, a Chinese scientist clandestinely sent him half a dozen, on which an Italian geneticist performed tests.[1]

Since then, China has prohibited foreign scientists from conducting research on the mummies. As Wong says, "Despite the political issues, excavations of the grave sites are continuing."[1]

See also

[edit]- Pazyryk culture

- Pontic–Caspian steppe

- Dzungarian Gate

- Gushi culture

- Tocharian clothing

- Kurgan hypothesis

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Wong, Edward (18 November 2008). "The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 237.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (15 March 2010). "A Host of Mummies, a Forest of Secrets". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ a b School of Life Sciences, Jilin University, China, (2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies", in ENA, European Nucleotide Archive.

- ^ Shuicheng, Li (2003). "Ancient Interactions in Eurasia and Northwest China: Revisiting J.G. Andersson's Legacy". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 75. Stockholm: Fälth & Hässler: 13. "Biological anthropological research indicates that the physical characteristics of those buried at Gumugou cemetery along the Kongque River near Lop Nur in Xinjiang are very similar to those of the Andronovo culture and Afanasievo culture people from Siberia in Southern Russia. This suggests that all of these individuals belong to the Caucasian physical type. Additionally, excavations in 2002 by Xinjiang archaeologists at the site of Xiaohe cemetery, first discovered by the Swedish archaeologist Folke Bergman, uncovered mummies and wooden human effigies that clearly have Europoid features. According to the preliminary excavation report, the cultural features and chronology of this site are said to be quite similar to those of Gumugou. Other sites in Xinjiang also contain both individuals with Caucasian features and ones with Mongolian features. For example, this pattern occurs at the Yanbulark cemetery in Xinjiang, but individuals with Mongoloid features are clearly dominant. The above evidence is enough to show that, starting around 2,000 BCE some so-called primitive Caucasians expanded eastward to the Xinjiang area as far as the area around Hami and Lop Nur. By the end of the second millennium, another group of people from Central Asia started to move over the Pamirs and gradually dispersed in southern Xinjiang. These western groups mixed with local Mongoloids resulting in an amalgamation of culture and race in middle Xinjiang east to the Tianshan."

- ^ Doumani Dupuy, Paula N. (November 2021). "The unexpected ancestry of Inner Asian mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 204–206. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..204D. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02872-1. PMID 34707262. S2CID 240072156.

The basin holds several intact Bronze Age cemeteries of a founding population known as the agropastoral Xiaohe culture, which formed around 2100 BCE in what were then freshwater environments (the Bronze Age spanned from about 3000 to 1000 BCE).

- ^ Zhang 2021, "Using qpAdm, we modelled the Tarim Basin individuals as a mixture of two ancient autochthonous Asian genetic groups: the ANE, represented by an Upper Palaeolithic individual from the Afontova Gora site in the upper Yenisei River region of Siberia (AG3) (about 72%), and ancient Northeast Asians, represented by Baikal_EBA (about 28%) (Supplementary Data 1E and Fig. 3a). Tarim_EMBA2 from Beifang can also be modelled as a mixture of Tarim_EMBA1 (about 89%) and Baikal_EBA (about 11%).".

- ^ Nägele, Kathrin; Rivollat, Maite; Yu, He; Wang, Ke (2022). "Ancient genomic research – From broad strokes to nuanced reconstructions of the past". Journal of Anthropological Sciences. 100 (100): 193–230. doi:10.4436/jass.10017. PMID 36576953.

Combining genomic and proteomic evidence, researchers revealed that these earliest residents in the Tarim Basin carried genetic ancestry inherited from local Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, carried no steppe-related ancestry, but consumed milk products, indicating communications of persistence practices independent from genetic exchange.

- ^ a b c Zhang 2021.

- ^ Zhang 2021, "Our results do not support previous hypotheses for the origin of the Tarim mummies, who were argued to be Proto-Tocharian-speaking pastoralists descended from the Afanasievo, or to have originated among the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex or Inner Asian Mountain Corridor cultures. Instead, although Tocharian may have been plausibly introduced to the Dzungarian Basin by Afanasievo migrants during the Early Bronze Age, we find that the earliest Tarim Basin cultures appear to have arisen from a genetically isolated local population that adopted neighbouring pastoralist and agriculturalist practices, which allowed them to settle and thrive along the shifting riverine oases of the Taklamakan Desert.".

- ^ Li, Xiao; Wagner, Mayke; Wu, Xiaohong; Tarasov, Pavel; Zhang, Yongbin; Schmidt, Arno; Goslar, Tomasz; Gresky, Julia (21 March 2013). "Archaeological and palaeopathological study on the third/second century BC grave from Turfan, China: Individual health history and regional implications". Quaternary International. 290–291: 335–343. Bibcode:2013QuInt.290..335L. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.05.010. ISSN 1040-6182.

The whole graveyard including tomb M2 belongs to the Subeixi culture, associated with the Cheshi (Chü-shih) state known from Chinese historical sources (Sinor, 1990). Archaeological and historical data attest it as society with a developed agro-pastoral economy, that existed in and north of the Turfan Basin (Fig. 1) during the first millennium BC. The Subeixi weaponry, horse gear and garments (Mallory and Mair, 2000; Lü, 2001) resemble those of the Pazyryk culture (Molodin and Polos'mak, 2007), suggesting contacts between Subeixi and the Scythians living in the Altai Mountains.

- ^ Mallory, J.P. (2015). "The Problem of Tocharian Origins: An Archaeological Perspective" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers: 24.

- ^ Benjamin, Craig (2018). Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE – 250 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-108-63540-0.

... the fact that in cemeteries such as Yanbulaq both Europoid and Mongoloid mummies have been found together, also indicates some degree of interaction between existing farming populations and newly arrived nomadic migrants from the West.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 10.

- ^ "A Craniometric Investigation of The Bronze Age Settlement of Xinjiang". Scribd. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

The results fail to demonstrate close phenetic affinities between the early inhabitants of Qa¨wrighul and any of the proposed sources for immigrants to the Tarim Basin. The absence of close affinities to outside populations renders it unlikely that the human remains recovered from Qa¨wrighul represent the unadmixed remains of colonists from the Afanasievo or Andronovo cultures of the steppe lands, or inhabitants of the urban centers of the Oxus civilization of Bactria.

- ^ Though modern Westerners tend to identify this type of hat as the headgear of a witch, there is evidence that these pointed hats were widely worn by both women and men in some Central Asian tribes. For instance, the Persian king Darius recorded a victory over the "Sakas of the pointed hats". The Subeshi headgear is likely an ethnic badge or a symbol of position in the society.

- ^ a b "The Mummies of Xinjiang". Discover. 1 April 1994.

- ^ Thornton, Christopher P.; Schurr, Theodore G. (2004). "Genes, language, and culture: an example from the Tarim Basin". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 23 (1): 83–106. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2004.00203.x.

- ^ Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Robitaille, Benoît; Krutak, Lars; Galliot, Sébastien (February 2016). "The World's Oldest Tattoos". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 5: 19–24. Bibcode:2016JArSR...5...19D. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007. S2CID 162580662.

- ^ Mair, Victor H. (1995). "Mummies of the Tarim Basin". Archaeology. 48 (2): 28–35 [30].

- ^ a b c Li, Chunxiang; Li, Hongjie; Cui, Yinqiu; Xie, Chengzhi; Cai, Dawei; Li, Wenying; Victor, Mair H.; Xu, Zhi; Zhang, Quanchao; Abuduresule, Idelisi; Jin, Li; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui (2010). "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age". BMC Biology. 8 (15): 15. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15. PMC 2838831. PMID 20163704.

- ^ Gao, Shizhu; Cui, Yinqiu; Yang, Yidai; Duan, Ranhui; Abuduresule, Idelisi; Mair, Victor H.; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of human remains from the Yuansha site in Xinjiang, China". Science in China Series C: Life Sciences. 51 (3): 205–213. doi:10.1007/s11427-008-0034-8. PMID 18246308. S2CID 1636381.

- ^ a b Li, Chunxiang; Ning, Chao; Hagelberg, Erika; Li, Hongjie; Zhao, Yongbin; Li, Wenying; Abuduresule, Idelisi; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui (2015). "Analysis of ancient human mitochondrial DNA from the Xiaohe cemetery: Insights into prehistoric population movements in the Tarim Basin, China". BMC Genetics. 16: 78. doi:10.1186/s12863-015-0237-5. PMC 4495690. PMID 26153446.

- ^ Li, 2010

- ^ 中国北方古代人群Y染色体遗传多样性研究 [Study on Genetic Diversity of Y-chromosome in Ancient Inhabitants of Northern China] (PhD) (in Chinese). Jilin University. 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ Hollard, Clémence; et al. (2018). "New genetic evidence of affinities and discontinuities between bronze age Siberian populations". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 167 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23607. PMID 29900529. S2CID 205337212.

- ^ a b c Coonan, Clifford (August 28, 2006). "A meeting of civilisations: The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Barber 1999, p. 72.

- ^ "Extended Data. Table 1. A summary of the Bronze Age Xinjiang individuals reported in this study". Nature.

- ^ Zhang 2021, "To understand this mixed genetic profile, we used qpAdm to explore admixture models of the Dzungarian groups with Tarim_EMBA1 or a terminal Pleistocene individual (AG3) from the Siberian site of Afontova Gora31, as a source (Supplementary Data 1D). AG3 is a distal representative of the ANE ancestry and shows a high affinity with Tarim_EMBA1.".

- ^ "Western China's mysterious mummies were local descendants of ice age ancestors". Science.org.

- ^ Zhang 2021, "Using qpAdm, we modelled the Tarim Basin individuals as a mixture of two ancient autochthonous Asian genetic groups: the ANE, represented by an Upper Palaeolithic individual from the Afontova Gora site in the upper Yenisei River region of Siberia (AG3) (about 72%), and ancient Northeast Asians, represented by Baikal_EBA (about 28%)".

- ^ Shan-Shan Dai, Xierzhatijiang Sulaiman, Jainagul Isakova, Wei-Fang Xu, Najmudinov Tojiddin Abdulloevich, Manilova Elena Afanasevna, Khudoidodov Behruz Ibrohimovich, Xi Chen, Wei-Kang Yang, Ming-Shan Wang, Quan-Kuan Shen, Xing-Yan Yang, Yong-Gang Yao, Almaz A Aldashev, Abdusattor Saidov, Wei Chen, Lu-Feng Cheng, Min-Sheng Peng, Ya-Ping Zhang (25 August 2022). "The Genetic Echo of the Tarim Mummies in Modern Central Asians". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang 2021, "We modelled the Tarim Basin individuals as a mixture of two ancient autochthonous Asian genetic groups: the ANE, represented by an Upper Palaeolithic individual from the Afontova Gora site in the upper Yenisei River region of Siberia (AG3) (about 72%), and ancient Northeast Asians, represented by Baikal_EBA (about 28%)".

- ^ Zhang 2021: "The Tarim mummies are among only a few known Holocene populations that derive the majority of their ancestry from Pleistocene ANE groups, who once made up the huntergatherer populations of southern Siberia, and which are represented by individual genomes from the archaeological sites of Mal'ta (MA-1)29 and Afontova Gora (AG3). (...) The Tarim mummies are currently the best representative of the pre-pastoralist ANE-related population that once inhabited Central Asia and southern Siberia (Extended Data Fig. 2A), even though Tarim_EMBA1 postdates these populations in time."

- ^ a b Mallory & Mair 2000, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Barber 1999, p. 119.

- ^ Kim, Ronald (2006). "Tocharian". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044299-0.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 236.

- ^ "A Craniometric Investigation of The Bronze Age Settlement of Xinjiang". Scribd. Retrieved 2024-04-08.

In fact, the early sample from westernChina, Qa¨wrighul (QAW), is identified as possessing closer affinities to the two samples from Harappa(HAR and CEMH)

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, p. 236–237.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, pp. 260, 294–296, 314–318.

- ^ Zhang 2021, "The Tarim mummies' so-called Western physical features are probably due to their connection to the Pleistocene ANE gene pool".

- ^ "A Craniometric Investigation of The Bronze Age Settlement of Xinjiang". Scribd. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

The results fail to demonstrate close phenetic affinities between the early inhabitants of Qa¨wrighul and any of the proposed sources for immigrants to the Tarim Basin. The absence of close affinities to outside populations renders it unlikely that the human remains recovered from Qa¨wrighul represent the unadmixed remains of colonists from the Afanasievo or Andronovo cultures of the steppe lands, or inhabitants of the urban centers of the Oxus civilization of Bactria.

- ^ Tikhvinskiĭ, Sergeĭ Leonidovich; Perelomov, Leonard Sergeevich (1981). China and her neighbours, from ancient times to the Middle Ages: a collection of essays. Progress Publishers. p. 124.

- ^ Mair, Victor H. (March–April 1995). "Mummies of the Tarim Basin". Archaeology. 48 (2): 28–35 [30].

- ^ Yu (2003), pp. 34–57, 77–88, 96–103.

- ^ Liu, Jianguo (2004), Distinguishing and Correcting the pre-Qin Forged Classics, Xi'an: Shaanxi People's Press, ISBN 7-224-05725-8

- ^ Baumer (2000), p. 28.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Martini, I. Peter (2010). Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases. Springer. p. 310. ISBN 978-90-481-9412-4.

- ^ Higham, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 0-8160-4640-9.

- ^ Chang, K.C.: Studies of Shang Archaeology, pp. 6–7, 1. Yale University Press, 1982.

- ^ Chang, K.C.: Studies of Shang Archaeology, p. 1. Yale University Press, 1982.

- ^ "Teaching Chinese Archaeology, Part Two". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ Li-Liu; The Chinese Neolithic, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- ^ Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China Heilbrunn Timeline Retrieved May 13, 2010

- ^ The Kingdom of Anxi

- ^ "Silk Road, North China", C. Michael Hogan, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham (2007)

- ^ "Expedition Magazine". www.Penn.Museum. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "The Eternal Mummy Princesses". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Ercilasun, Konuralp (2018). "Introduction: The Land, the People, and the Politics in a Historical Context". In Kurmangaliyeva Ercilasun, Güljanat; Ercilasun, Konuralp (eds.). The Uyghur Community. Politics and History in Central Asia. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-52297-9_1. ISBN 978-1-137-52297-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Demick, Barbara (21 November 2010). "A beauty that was government's beast". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Barber 1999, pp. 71–87

- ^ "Ancient Mummies of the Tarim Basin | Expedition Magazine". www.Penn.Museum. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Matthew (2012). "The 'Silk Roads'in Time and Space: Migrations, Motifs, and Materials" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers: 96–97.

- ^ "Beauty of Kroran (Book description)".

- ^ Mair, V.H. (2010). "The mummies of east central Asia". Expedition, 52(3), 23–32.

- ^ Cheang, Sarah; Greef, Erica de; Takagi, Yoko (2021). Rethinking Fashion Globalization. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-350-18130-4.

- ^ Wang, Tingting; Fuller, Benjamin T.; Jiang, Hongen; Li, Wenying; Wei, Dong; Hu, Yaowu (13 January 2022). "Revealing lost secrets about Yingpan Man and the Silk Road". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 669. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12..669W. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04383-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8758759. PMID 35027587.

References

[edit]- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1999). The Mummies of Ürümchi. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-36897-4.

- Baumer, Christoph (2000). Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. Bangkok: White Orchid Books. ISBN 974-8304-38-8.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine; Behan, Mona (2002). Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines (1stTrade ed.). New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67983-6.

- Hemphill, Brian E.; Mallory, J.P. (2004). "Horse-mounted invaders from the Russo-Kazakh steppe or agricultural colonists from Western Central Asia? A craniometric investigation of the Bronze Age settlement of Xinjiang". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 125 (3): 199–222. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10354. PMID 15197817.

- Larsen, Clark Spencer (2002). "Bioarchaeology: The Lives and Lifestyles of Past People". Journal of Archaeological Research. 10 (2) (published June 2002): 119–166. doi:10.1023/A:1015267705803. S2CID 145654453.

- Li, Shuicheng (1999). "A Discussion of Sino-Western Cultural Contact and Exchange in the Second Millennium BC Based on Recent Archeological Discoveries". Sino-Platonic Papers (97) (published December 1999).

- Light, Nathan (1999a). "Hidden Discourses of Race: Imagining Europeans in China". Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Light, Nathan (March–April 1999b), "Tabloid Archaeology: Is Television Trivializing Science?", Discovering Archaeology, pp. 98–101, archived from the original on 2006-09-20

- Liu, Xinru (2001), "Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan. Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies", Journal of World History, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 261–292, doi:10.1353/jwh.2001.0034, S2CID 162211306

- Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History

- Schurr, Theodore G. (2001). "Tracking Genes Across the Globe: A review of Genes, Peoples, and Languages, by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza". American Scientist. Vol. 89, no. 1 (published January–February 2001). Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- Chengzhi, Xie; Chunxiang, Li; Yinqiu, Cui; Dawei, Cai; Haijing, Wang; Hong, Zhu; Hui, Zhou (2007). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of ancient Sampula population in Xinjiang". Progress in Natural Science. 17 (8): 927–933. doi:10.1080/10002007088537493.

- Yu, Taishan (2003), A Comprehensive History of Western Regions (2nd ed.), Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Guji Press, ISBN 7-5348-1266-6

- Zhang, Fan (November 2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 256–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..256Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8580821. PMID 34707286.

External links

[edit]- Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? pdf

- High-quality images of Tarim-basin mummies

- Images of the Tocharian mummies Includes the face of the "Beauty of Loulan" as reconstructed by an artist.

- "The Takla Makan Mummies". PBS. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Genetic testing reveals awkward truth about Xinjiang's famous mummies (AFP) Khaleej Times Online, 19 April 2005

- The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To The New York Times, 18 November 2008

- 'A Host of Mummies, A Forest of Secrets', Nicholas Wade, The New York Times, 15 March 2010.