User:Hintha/sandbox2

မြန်မာလူမျိုး | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

c. 51 million (2014) | |

| 1,418,472 (2014)[1] | |

| 303,996 (2014)[1] | |

| 200,000 (2017)[2] | |

| 189,000 (2019)[3] | |

| 92,263 (2014)[1] | |

| 49,204 (2016)[4] | |

| 35,049 (2020)[5] | |

| 17,975 (2014)[1] | |

| 14,592 (2014)[1] | |

| 9,335 (2016)[6] | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of Myanmar, including Burmese, Shan, Karenic languages, Rakhine, Kachin, Mon, Kuki-Chin languages, and Burmese English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Theravada Buddhism Minority Islam · Christianity · Hinduism · Animism | |

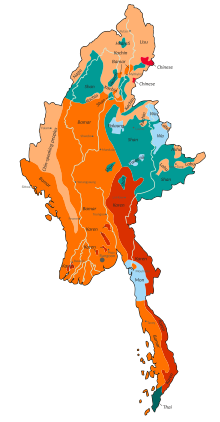

Burmese people or Myanma people (Burmese: မြန်မာလူမျိုး) are citizens or people from Myanmar (Burma), irrespective of their ethnic or religious background. Myanmar is a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-lingual country. The Burmese government officially recognises 135 ethnic groups, who are grouped into eight 'national races,' namely the Bamar (Burmans), Shan, Karen, Rakhine (Arakanese), Mon, Kachin, Chin, and Kayah (Karenni).[7] Many ethnic and ethnoreligious communities exist outside these defined groupings, such as the Burmese Chinese and Panthay, Burmese Indians, Anglo-Burmese, and Gurkhas.

The 2014 Myanmar Census enumerated 51,486,253 persons.[8] There is also a substantial Burmese diaspora, the majority of whom have settled in neighbouring Asian countries.[1] Refugees and asylum seekers from Myanmar make up one of the world's five largest refugee populations.[9][10]

Concept of taing-yin-tha

[edit]

Similar to the concepts of pribumi in Indonesia and bumiputera in Malaysia, Burmese society categorises indigenous peoples who had historically lived in what is now modern-day Myanmar as taing-yin-tha (တိုင်းရင်းသား)[11], which is typically translated as 'national race' or 'indigenous race.' Taing-yin-tha literally means 'those who form the basis of the state' or 'offspring of a region.'[12][13]

The Burmese government officially recognizes officially 135 taing-yin-tha ethnic groups (တိုင်းရင်းသားလူမျိုး) as “original inhabitants” who lived in Myanmar before the first British annexation of Lower Burma in 1824.[7] These 'ethnic' designations have been challenged and disputed for being exclusionary and arbitrary legacies of colonialism, which "reified and rigidified ethnic identities," inevitably sowing political and economic divisions along ethnic lines.[7][14] In the pre-colonial era, cultural identities were fluid and dynamic, defined on the basis of patron–client relationships, religions, and regions.[7][14]

Ethnic identity in Myanmar has been significantly shaped by colonialism de-colonisation. During the early colonial era, the term taing-yin-tha was not politically salient.[11] In the 1950s, the term was used to promote solidarity among indigenous peoples.[12] In the 1960s, the term had evolved in meaning, acquiring a more prescriptive definition, specifically referencing the country's eight 'national races', i.e., the Bamar (Burmans), Shan, Karen, Rakhine (Arakanese), Mon, Kachin, Chin, and Kayah (Karenni).[12] Following the 1962 Burmese coup d'état, this term began to acquire political saliency, central to the Burmese military's nation-building programme, which closely linked indigenous heritage with rights to Burmese citizenship.[15]

In the 1980s, the government formally categorised ethnolinguistic groups into 135 subcategories within the construct of the eight national races, an idea which was further propagated by the military junta following the 1988 coup and has remained the official framework for categorising the country's diverse communities.[13] Myanmar's seven states are named after each of the national races, with the exception of the Bamar, who have traditionally lived in the country's seven regions (formerly called divisions).[16]

Burmese diaspora

[edit]The Burmese diaspora refers to families and individuals who have migrated to other parts of the world from Myanmar. Myanmar has experienced significant waves of population displacement, due to decades of internal conflict, poverty, and political persecution,[17] often triggered by political events like the 1962 Burmese coup d'état, the 8888 Uprising and ensuing 1988 coup d'état, and most recently, the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état.[18][19] The diaspora is broadly categorised into 3 groups: religious minorities and ethnic groups who have fled conflict areas, elites seeking more politically stable environments, and others seeking improved educational and economic opportunities.[17] In 2021, 1.2 million refugees and asylum seekers were from Myanmar, making them the world's fifth largest refugee population, behind Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, and South Sudan.[9][10]

The diaspora in neighbouring Asian countries generally work in unskilled labour sectors (e.g., agriculture, fishing, manufacturing, etc.) while increasing numbers of white collar workers have resettled in the Western world.[17] The significant brain drain of entrepreneurs, professionals and intellectuals resulting from continued decline in Myanmar's sociopolitical environment have had significant ramifications on the country's economic development, particularly in terms of human capital.[20] The recent military coup in 2021 has resulted in the exodus of repatriates of Burmese nationality (e.g., professionals, executives and investors) as well as expatriates alike, impacting the country's emerging start-up scene.[21]

Thailand is the most popular destination for Burmese migrants; two million Burmese people live in Thailand.[17] According to the 2014 Census, 70% of overseas Burmese reside in neighboring Thailand, followed by Malaysia, China, and Singapore.[1] Overseas Burmese also live in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Japan, and South Korea. Following the 1962 Burmese coup d'état, between 1963 and 1970, 155,000 Burmese Indians were repatriated to India and resettled by the Indian government in ‘Burma Colonies’ in cities like Chennai, Tiruchirappalli and Madurai.[22] Outside of Asia, there is also a significant diaspora in the United States, Australia, United Kingdom, and New Zealand.

Genetics

[edit]Myanmar sits at the confluence of East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Genetic analyses of Myanmar's population has indicated that Myanmar's haplogroup distribution shows a typical Southeast Asian pattern, but also Northeast Asian and limited Indian influences.[23] One study found that the Bamar and Karen, although both speak related Tibeto-Burman languages, are genetically disparate, with the Bamar showing extraordinary degrees of genetic diversity and the Karen displaying greater degrees of genetic isolation.[23] Another study of basal lineages suggests that Myanmar was likely one of the differentiation centers of early modern humans.[24] There is also observed genetic divergence within genetic populations, with the Bamar, Rakhine, and Karen showing closer affinity with Tai-Kadai and Hmong-Mien populations in Southeast Asia, and the Naga and Chin showing closer genetic ties with Austro-Asiatic and Tibeto-Burman populations in northeast India.[24]

See also

[edit]- List of ethnic groups in Myanmar

- Migration period of ancient Burma

- Myanmar nationality law

- Burmese diaspora

- Demographics of Myanmar

- Languages of Myanmar

- Culture of Myanmar

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "The Union Report - Census Report Volume 2". The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census. Department of Population, Ministry of Immigration and Population. May 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Ma, Alex (2017-01-17). "Labor Migration from Myanmar: Remittances, Reforms, and Challenges". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ Budiman, Abby. "Burmese in the U.S. Fact Sheet". Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ "Myanmar (Burmese) Culture". Cultural Atlas. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ "Japan to let Myanmar students and interns stay after visas expire". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2017-02-08). "Census Profile, 2016 Census - Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ a b c d Thawnghmung, Ardeth Maung (2022-04-20). ""National Races" in Myanmar". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.656. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ "The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census: Highlights of the Main Results" (PDF). Ministry of Immigration and Population. May 2015.

- ^ a b "UNHCR - Refugee Statistics". UNHCR. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ a b "Myanmar situation". Global Focus. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ a b Cheesman, Nick (2017-05-27). "How in Myanmar "National Races" Came to Surpass Citizenship and Exclude Rohingya". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 47 (3): 461–483. doi:10.1080/00472336.2017.1297476. ISSN 0047-2336.

- ^ a b c Nishikawa, Yukiko (2022-03-07). International Norms and Local Politics in Myanmar. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-54588-3.

- ^ a b "Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar". International Crisis Group. 2020-08-28.

- ^ a b Clarke, Sarah L; Seng Aung Sein Myint; Zabra Yu Siwa (2019-05-31). "Re-examining Ethnic Identity in Myanmar" (PDF). Centre for Peace & Conflict Studies.

- ^ Solomon, Richard (2017-05-15). "Myanmar's 'national races' trump citizenship". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ Selth, Andrew (2020-12-10). Interpreting Myanmar: A Decade of Analysis. ANU Press. ISBN 978-1-76046-405-9.

- ^ a b c d "Diaspora Organizations and their Humanitarian Response in Myanmar - Myanmar". ReliefWeb. 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ "Myanmar; Brain Drain Again? - Issue 32". Myanmar Peace Monitor. December 2021. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "Young People Clamour to Leave Myanmar in Giant Brain Drain". The Irrawaddy. 2022-08-18. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ MAUNG, MYA (1992). "DAMAGE TO HUMAN CAPITAL AND THE ECONOMIC FUTURE OF BURMA". The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs. 16 (1): 81–97. ISSN 1046-1868.

- ^ Caillaud, Romain (2022). "Myanmar's Economy in 2021: The Unravelling of a Decade of Reforms". Southeast Asian Affairs.

- ^ Nainar, Nahla (2021-02-24). "How the Tamil link with Burma has endured down the years". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ a b Summerer, Monika; Horst, Jürgen; Erhart, Gertraud; Weißensteiner, Hansi; Schönherr, Sebastian; Pacher, Dominic; Forer, Lukas; Horst, David; Manhart, Angelika; Horst, Basil; Sanguansermsri, Torpong; Kloss-Brandstätter, Anita (2014-01-28). "Large-scale mitochondrial DNA analysis in Southeast Asia reveals evolutionary effects of cultural isolation in the multi-ethnic population of Myanmar". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-17. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3913319. PMID 24467713.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Li, Yu-Chun; Wang, Hua-Wei; Tian, Jiao-Yang; Liu, Li-Na; Yang, Li-Qin; Zhu, Chun-Ling; Wu, Shi-Fang; Kong, Qing-Peng; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2015-03-26). "Ancient inland human dispersals from Myanmar into interior East Asia since the Late Pleistocene". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 9473. doi:10.1038/srep09473. ISSN 2045-2322.