Walvis Bay 2-4-2T Hope

| Walvis Bay 2-4-2T Hope | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The engine Hope plinthed in Windhoek, c. 1950 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Walvis Bay 2-4-2T Hope of 1899 was a South African steam locomotive from the pre-Union era in the Cape of Good Hope.

In 1899, the Walvis Bay Tramway in the British territory of Walvis Bay, a Cape of Good Hope exclave in German South West Africa, placed a single 2-4-2T locomotive in service. It remained in service until 1915, when a Cape gauge railway was opened between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay.[1][2][3]

Walvis Bay Tramway

[edit]The British territory surrounding the port of Walvis Bay in Deutsch-Südwest-Afrika (DSWA), an exclave with an area of 434 square miles (1,124 square kilometres), was administered as part of the Cape of Good Hope. The Walvis Bay railway began as a 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauge horse-drawn tramway within the confines of the harbour town. The gauge was most probably selected to ensure a wide enough path for horses between the rails, as was probably also the case on the light mule-drawn Namaqualand Railway which was built to the same gauge between Port Nolloth and O'okiep in northwestern Cape of Good Hope.[1][4]

Manufacturer

[edit]In June 1899, a single 2-4-2T locomotive was shipped from Kerr, Stuart and Company of Stoke-on-Trent in England. It arrived in Walvis Bay on 22 August 1899 aboard the barque Primera, along with a distilling plant, railway trucks and 200 tons of coal. The engine was named Hope and was placed in service on the short Walfish Bay Tramway.[1][2][3][5][6]

The locomotive was a standard Sirdar class engine, similar to the two Class NG1 0-4-0T locomotives which were to enter service on the Bezuidenhout Light Railway a year later during the Second Boer War, but with leading and trailing pony wheels added and a tropical cab roof. Kerr, Stuart was a supplier of contractor's engines and often built locomotives to standard designs, but without frame stretchers and axles. These semi-completed locomotives were kept in stock until an order was placed. This allowed them to be delivered with a minimum of delay.[7]

Characteristics

[edit]The engine was built on 5⁄8 inch (16 millimetres) thick plate frames, arranged outside the coupled wheels. It had a boiler with an inside diameter of 2 feet 1 inch (635 millimetres), set at an operating pressure of 120 pounds per square inch (827 kilopascals). Its inclined cylinders were arranged outside the plate frames and had a bore of 6 inches (152 millimetres) and a 10 inches (254 millimetres) stroke. It used Murdoch's D type slide valves, actuated by Stephenson valve gear through rocker arms.[1]

It had coupled wheels of 24 inches (610 millimetres) diameter. The coal bunker had a capacity of 5 long hundredweight (0.3 tonnes) and the side-tanks had a water capacity of 100 imperial gallons (455 litres). The total weight of the engine in full working order was 12 long tons (12,190 kilograms) and it had a tractive effort of 1,020 pounds-force (4.5 kilonewtons) at 75% of boiler pressure.[1]

Walvis Bay Railway

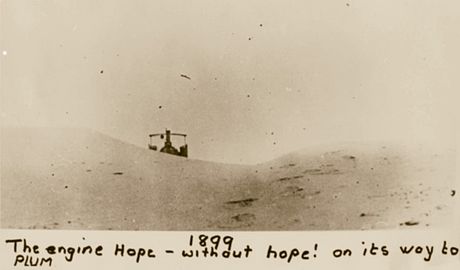

[edit]In 1899, the Cape government began to extend the tramway as a railway to a terminus named Plum, 11 miles (18 kilometres) due east of Walvis Bay near Rooibank, essentially in the middle of the Namib desert on the DSWA border. The decision to build the 12-mile long (19-kilometre) railway between the harbour and the international border with DSWA followed the start of construction of the Swakopmund-Windhuk Staatsbahn in DSWA in 1897 and was an attempt to not forfeit freight trade opportunities into the interior once that line was completed.[2][3]

The object with the railway was to bridge the region of shifting sand dunes between the harbour and the interior so that goods could be forwarded by rail to Plum and then by ox wagon from there into the interior. The extension was completed in 1903, but saw very limited use, mainly to obtain firewood and to render possible the occasional picnic in the desert.[1][3]

Service

[edit]The engine Hope operated on the railway for some five years, until it became apparent by 1904 that the short link had no economic benefit. In March 1905, the Acting Magistrate reported an income over two years of £39 against expenditure of £1,200. By then, sections of track of more than 1⁄2 mile (0.8 kilometres) had been buried during a sandstorm under 30 feet (9 metres) high dunes.[2][3]

The main reason for the abandonment of the railway was the opening of the copper mines at Tsumeb and the construction of the Otavi Railway, which commenced in November 1903 to connect Tsumeb with the port of Swakopmund, just north of the DSWA border. The locomotive continued to work the 3 miles (5 kilometres) of remaining track in and about the settlement, working cargo in the harbour and removing insanitary rubbish to a safe distance from the village.[2][3]

Preservation

[edit]After a Cape gauge railway was opened between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay in March 1915, the locomotive remained stored in a local siding in Walvis Bay for years, until it was repaired for preservation by the South African Railways administration and plinthed in Windhoek during the 1940s. It was returned to Walvis Bay in 1963, to be plinthed at Walvis Bay railway station. To protect it against Walvis Bay's notoriously corrosive sea air, the engine has since been enclosed in a glass cage.[2][3]

Illustration

[edit]-

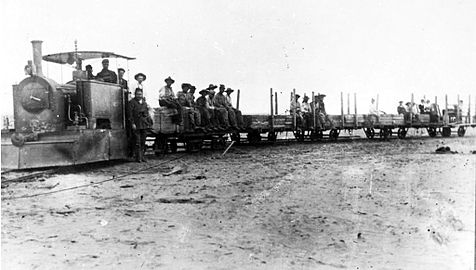

Hope on a work train, c. 1899

-

Hope on the way to Plum, c. 1899

-

Hope plinthed in a glass cage at Walvis Bay, 2016

-

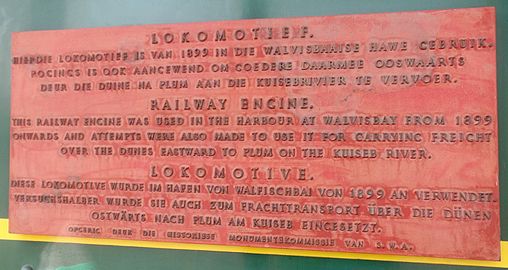

Plaque on Hope in Afrikaans, English and German, Walvis Bay, 2016

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1948). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, January 1948. p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f Dulez, Jean A. (2012). Railways of Southern Africa 150 Years (Commemorating One Hundred and Fifty Years of Railways on the Sub-Continent – Complete Motive Power Classifications and Famous Trains – 1860–2011) (1st ed.). Garden View, Johannesburg, South Africa: Vidrail Productions. p. 379. ISBN 9 780620 512282.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lee, Charles E. (1951). The Walfish Bay Railway. Article in The Railway Magazine with which is incorporated "Transport & Travel Monthly", September 1951. Tothill Press Limited, London. pp. 627-628, 631.

- ^ Walvis Bay: exclave no more, Ieuan Griffiths, Geography, Vol. 79, No. 4 (October 1994), page 354 (Accessed on 10 July 2016)

- ^ Jux, Frank (1991). Kerr Stuart & Co. Ltd. Locomotive Works List. Compiled and published by Frank Jux.

- ^ SAR-L Group. South African Railways Fans, Yahoo! Groups message no. 51279, 11 July 2016.[dead link] (Accessed on 12 July 2016)

- ^ Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0869772112.