Wicked City (1987 film)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

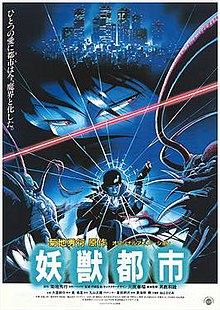

| Wicked City | |

|---|---|

Japanese film poster | |

| Kanji | 妖獣都市 |

| Literal meaning | 'Supernatural Beast City' |

| Revised Hepburn | Yōjū Toshi |

| Directed by | Yoshiaki Kawajiri |

| Screenplay by | Norio Osada |

| Based on | Wicked City: Black Guard by Hideyuki Kikuchi |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Kinichi Ishikawa |

| Edited by | Harutoshi Ogata |

| Music by | Osamu Shoji |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Joy Pack Film[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Wicked City (Japanese: 妖獣都市, Hepburn: Yōjū Toshi, lit. 'Supernatural Beast City') is a 1987 Japanese adult animated dark fantasy[2] action horror film[3] produced by Video Art and Madhouse for Japan Home Video. Based on Black Guard, the first novel of the Wicked City series by Hideyuki Kikuchi, the film is the solo directorial debut of Yoshiaki Kawajiri, who also served as the character designer, storyboard artist, animation director, and a key animator.

The story takes place towards the end of the 20th century and explores the idea that the human world secretly coexists with the demon world with a secret police force known as the Black Guard protecting the boundary.

With its confluence of gothic themes and graphic, erotic violence, Wicked City is today considered a prime example of science fiction anime from Japan's bubble economy period.[citation needed]

Plot

[edit]The existence of the "Black World"—an alternate dimension populated by supernatural demons—is known to few humans. For centuries, a peace treaty between the Black World and the world of humans has been maintained to ensure relative harmony. Both sides of the continuum are protected by an organization of secret agents called the Black Guard, specifically from a group of radicalized members of the Black World.

In Tokyo, Renzaburō Taki, a salaryman for an electronics company by day, and a Black Guard when needed, has sex with Kanako, a young woman who he has been meeting at a local bar for three months. Kanako reveals herself to be a spider-like doppelgänger from the Black World Radicals and escapes with a sample of Taki's semen after attempting to kill him. The next day, Taki is assigned to protect Giuseppe Mayart, a comical and perverted 200-year-old mystic who is a signatory for a ratified treaty between the Human World and the Black World, and a target for the Radicals. Taki is also informed that he will be working with a partner: a Black Guard from the Black World.

While awaiting Mayart's arrival at Narita, Taki is attacked by two Radicals at the runway, but is saved by his partner—a beautiful fashion model named Makie. Taki and Makie eventually meet Mayart; the trio take shelter in a Hibiya hotel with spiritual barriers to protect it from Radicals. While playing chess to pass time, the hotelier explains to Taki, who is unsure of his responsibilities within the Black Guard, that he will only value his position once he knows what he is protecting. During an assault on the hotel by a Radical named Jin (an invention of Kawajiri's), Mayart sneaks out.

Makie and Taki find him in a soapland in the grip of a Radical who has sapped his health, prompting a frantic trip to a spiritual hospital under Black Guard protection. Halfway there, Makie is taken prisoner by a tentacle demon, and Taki is forced to leave her behind. Upon their arrival at the clinic, Mayart begins his recovery, while Mr. Shadow—the leader of the Radicals—uses a psychic projection to taunt Taki into rescuing Makie. Ignoring Mayart's threats that he will be fired, he pursues Shadow to a dilapidated building far from the hospital, where he finds Makie being gang raped by Radicals. A female Radical attempts to seduce Taki, asking him if he ever copulated with Makie, but he kills her and the Radicals violating Makie, and wounds Shadow.

While tending to each other, Makie reveals to Taki that she was once romantically involved with a member of the Radicals, and that she joined the Black Guard because of her belief in the need for peace between the two worlds. Upon returning to the clinic, the pair are fired by Taki's superior, who deems Taki's desires a liability to his duties. While driving through a tunnel with a stowaway Mayart, they are ensnared by Kanako, who—having determined that Taki and Makie were partnered for genetic reasons—attempts to kill them again. Bolts of supernatural lightning kill Kanako, while Taki and Makie are wounded. They later awaken inside a church, and passionately make love.

A final attack by Shadow comes against Taki and Makie, which is deflected by more lightning generated by a surprisingly healthy Mayart, who reveals that he was actually hired to protect his "bodyguards". Mayart and Taki almost succeed in defeating Shadow, but the final blow comes from Makie, whose powers have increased due to her being impregnated by Taki. Mayart explains that the two are essential to the new peace treaty; Taki and Makie were selected to be the first couple from both worlds that can produce half-human, half-demon children, and their bond will be instrumental in ensuring everlasting peace between the two worlds. Although angry with Mayart because they were not informed of the Black Guard's plans, Taki implicitly admits that he loves Makie and, per the hotelier's advice, wants to protect her and their child. The trio leave to attend the peace ceremony. Taki remains in the Black Guard to ensure the protection of both worlds and his loved ones.

Cast

[edit]| Character | Japanese | English (Streamline, 1993)[4] |

English (Manga UK, 1993)[5] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renzaburō Taki | Yūsaku Yara | Gregory Snegoff | Stuart Milligan |

| Makie | Toshiko Fujita | Gaye Kruger | Tamsin Hollo |

| Giuseppe Mayart | Ichirō Nagai | Mike Reynolds | George Little |

| Mr. Shadow | Takeshi Aono | Jeff Winkless | Ray Lonnen |

| Kanako/Spider Woman | Mari Yokoo | Edie Mirman | Liza Ross |

| Black Guard President | Yasuo Muramatsu | Robert V. Barron | Graydon Gould |

| Hotelier | Tamio Ōki | David Povall | William Roberts |

| Jin | Kōji Totani | Kerrigan Mahan (uncredited) | Brian Note (uncredited) |

| Soap Girl | Arisa Andou | Joyce Kurtz (uncredited) | Pamela Merrick (uncredited) |

| Clinic Director | Kazuhiko Kishino | Edward Mannix (uncredited) | Douglas Blackwell (uncredited) |

| Bartender | Ikuya Sawaki | Jason Klassi | Adam Henderson (uncredited) |

| Demon Temptress | Asami Mukaidono | Eleni Kelakos | Liza Ross |

| Doctor | Masato Hirano | John Dantona (uncredited) | Adam Henderson (uncredited) |

| Demons | Ginzō Matsuo (uncredited)[6] Bin Shimada (uncredited)[6] |

Michael McConnohie (uncredited) Carl Macek (uncredited) |

William Roberts |

| Taki's Coworkers | Seiko Nakano (uncredited)[7] Kenichi Ogata (uncredited)[7] |

Melora Harte Steve Kramer |

Pamela Merrick (uncredited) Bob Sessions (uncredited) |

| Secretary | Naoko Watanabe (uncredited)[7] | Alexandra Kenworthy | Tamsin Hollo |

| Narrator | Yūsaku Yara | Gregory Snegoff | Bob Sessions (uncredited) |

Production

[edit]Yoshiaki Kawajiri had just completed his work directing The Running Man, a segment from the portmanteau film Neo-Tokyo (1987), and was asked to direct a 35-minute OVA short film based on Hideyuki Kikuchi's novel. Writing under the pseudonym "Kisei Chō",[8] Norio Osada's original draft of the screenplay began with Makie's saving of Taki from two demons at Narita, and ended with Taki's first battle with Mr. Shadow and rescue of Makie. After Japan Home Video were shown the first 15 minutes of completed animation, they were impressed enough with Kawajiri's work that the runtime was extended to 80 minutes. Kawajiri saw this as an opportunity to explore more characterization and created more animation for the start, the middle and the end. The project was completed in under a year.[9][10]

Hayao Miyazaki was reportedly so impressed by Kazuo Oga's art direction that he hired Oga for My Neighbor Totoro (1988).[9]

Release

[edit]Although classified as OVA by JHV, it was released theatrically in Japan by Joy Pack Film on 19 April 1987 and received a western release dubbed by Streamline Pictures under the name Wicked City on 20 August 1993. After Streamline Pictures lost the distribution rights, it was licensed and distributed by Urban Vision. A censored version of the film was distributed by Manga Entertainment in the UK with a different dub. Both the Streamline and Manga UK dubs were released in Australia, with the Manga UK dub being released on VHS in 1994. In 1995, Manga Video released in Australia a bundle VHS consisting of Wicked City and Monster City, this version containing the Streamline dub. In 1997 when Madman Entertainment was named distributor for Manga in Australia, the Streamline dub was released on a single tape, and the Manga UK version was phased out. On 26 July 2015, Discotek Media announced at their Otakon panel that they have acquired the movie and re-released the movie on DVD in 2016 with a new video transfer and with both Streamline and Manga UK English dubs.[11] On 28 September 2018, Toei announced a Region 2 Blu-ray release of the OVA to be released on 9 January 2019.[12]

Critical reception

[edit]Charles Solomon of the Los Angeles Times stated that the film epitomizes the "sadistic, misogynistic erotica" popular in Japan. He noted that Yoshiaki Kawajiri composes scenes like a live-action filmmaker, and complimented his deft cutting and camera angles, but felt that the "Saturday-morning style animation" and juvenile story did not warrant the effort. Solomon also opined that Kisei Choo's screenplay was inscrutable. Solomon concluded his review by touching upon the belief that there is a connection between screen violence and real-life violence by pointing out that Japan is one of the least violent societies in the industrialized world.[13]

Desson Howe of The Washington Post, who observed the level of violence toward women in the film, characterized it as a "post-Chandler, quasi-cyberpunky violence fest". Howe found the film compelling for its "gymnastic" camera angles, its kinetic pace and imaginative (if slightly twisted) images." He also found the English dubbing laughable, though he saw ominous subtext in various bits of dialogue and other moments in the film.[14]

Richard Harrigton, also of The Washington Post, saw the film as an attempt to create the Blade Runner of Japanese animation, citing its distinctively languid pace, linear storytelling and gradual exposition. Harrington also detected a Brave New World subtext, and calling it "stylish and erotic, exciting in its limited confrontations and provocative in its ambition."[15]

Marc Savlov of The Austin Chronicle gave the film two and a half out of five stars, calling it a "better-than-average" treatment of the "demons from an alternate universe" subject matter. Savlov stated that the film was easier to follow than Urotsukidōji: Legend of the Overfiend, due to Wicked City's more linear and rapid storyline, and the lack of flashbacks and cyberpunk jargon that Savlov disliked in the genre. Savlov also appreciated the clarified animation. Savlov commented, "This may not be the second coming of Akira, but it's a step in the right direction."[16]

Bob Strauss from Animation Magazine described it as "one of the strongest features to come out of Japan’s anime", presenting a seemingly incoherent scenario that "makes more sense as it climaxes, revealing a few solid, thematic reasons for what initially seemed to be inexplicable behavior, gratuitous sex and reckless sci-fi gimmickry." He added that there was also a "neat moral and spiritual subtext to the whole bizarre enterprise."[17]

Chuck Arrington of DVD Talk, reviewing the DVD of the film, recommended that consumers "skip it", citing the transfer errors and scratches on the print, the at-times washed-out colors, and the uninteresting lengthy interview among the DVD's extras. Arrington thought that the visuals and the fight scenes were generally done well, and that the dubbing into English was acceptable, though exhibited some "wooden elements" endemic to all anime titles. Regarding the sexual violence in the film, Arrington found it excluded recommendation for most viewers, commenting, "Though not nearly as gruesome as Legend of the Overfiend, Wicked City is definitely not for children and not really for adults either."[18]

Theron Martin of Anime News Network said that "in all, Wicked City isn't great fare, but if explicit, sexually-charged supernatural action stories appeal to you then it should fit the bill quite nicely."[19]

Literary critic Susan J. Napier describes the film in her book, Anime From Akira to Princess Mononoke, as having similar depictions of the female body as its contemporaries: objects to be "viewed, violated, tortured" while also being "awesomely powerful, almost unstoppable". She credits the film's more nuanced and artistic approach within this context, but cites the metamorphoses of the female Black World agents as the film's ideas about female sexuality being limited to "an essentially conservative fantasy", with the powerful women's bodies being ultimately destroyed in "lengthy scenes of graphic violence".[20]

In John Hackett and Sean Harrington's Beasts of the Deep: Sea Creatures and Popular culture, the authors place The Wicked City alongside Hokusai’s octopus prints as re-establishing a link between the maritime and the erotic.[21]

Some of the film's fight scenes were featured in Manga Production's Mean & Mercenary VHS compilations.[22]

Live-action remake

[edit]Wicked City, a Hong Kong live-action adaptation of the film was made in 1992 produced by Film Workshop Ltd. The film was directed by Tai Kit Mak, produced and written by Tsui Hark, and starred Jacky Cheung, Leon Lai, Michelle Reis, Yuen Woo-ping, Roy Cheung, and Tatsuya Nakadai. (Michelle Reis said that Tsui Hark actually directed many scenes himself.[23][full citation needed])

The story takes place in Hong Kong during a conflict between worlds of Humans and "Rapters". Special police in the city are investigating a mysterious drug named "happiness". Taki, one of the police, meets his old lover Windy, who is a rapter and now mistress of a powerful old rapter named Daishu. Taki and other special police track down and fight Daishu, but later find that he hopes to coexist with human. The son of Daishu, Shudo, is the mastermind. In the end, Shudo is defeated, but Daishu and Taki's friends die too. Windy leaves alone.

References

[edit]- ^ "Wicked City". Japan Movie Database. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Murillo, Aimee (8 March 2019). "Sweet Streams: Dodging Dark Demons in 'Wicked City'". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Osmond, Andrew (29 September 2020). "Manga Entertainment Will Release Double Pack of Wicked City and Demon City Shinjuku". Anime News Network. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Wicked City (movie)". CrystalAcids. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Wicked City (UK Ending Credits) (DVD). Altamonte Springs, Florida: Discotek Media. 1987.

- ^ a b Lepe, Santiago Reveco (15 February 2020). "I think Ginzo Matsuo and Bin Shimada voiced the demons". @SantiagoReveco. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Lepe, Santiago Reveco (15 February 2020). "I think it's Seiko Nakano and Kenichi Ogata for Taki's co-workers and Naoko Watanabe for the secretary". @SantiagoReveco. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ "協同組合日本シナリオ作家協会".

- ^ a b Wicked City (Audio Commentary with Mike Toole) (DVD). Altamonte Springs, Florida: Discotek Media. 1987.

- ^ Wicked City (Interview with Yoshiaki Kawajiri) (DVD). Altamonte Springs, Florida: Discotek Media. 1987.

- ^ "Discotek Adds 1976 Gaiking, Wicked City Anime". Anime News Network. 26 July 2015.

- ^ "「妖獣都市」&「魔界都市」特集 | 東映ビデオオフィシャルサイト". 28 September 2018.

- ^ Solomon, Charles (25 February 1994). "Movie Review: Animated Bondian Bondage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Howe, Desson (28 January 1994). "‘Wicked City’ (NR)". the Washington Post.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (28 January 1994). "Wicked City (NR)". The Washington Post.

- ^ Savlov, Marc (4 February 1994). "Wicked City". The Austin Chronicle.

- ^ Patten, Fred. "Streamline Pictures – Part 16: "Wicked City"". Cartoon Research. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Arrington, Chuck (3 December 2000). "Wicked City". DVD Talk. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Martin, Theron (13 March 2016). "Wicked City DVD – Remastered Special Edition". Anime News Network. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Napier, Susan J. (2001), Napier, Susan J. (ed.), "Controlling Bodies: The Body in Pornographic Anime", Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 63–83, doi:10.1057/9780312299408_4, ISBN 978-0-312-29940-8, retrieved 19 September 2023

- ^ Hackett, Jon; Harrington, Seán, eds. (2018). Beasts of the deep: sea creatures and popular culture. East Barnet, Herts, United Kingdom: John Libbey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86196-939-5.

- ^ "Mean & Mercenary" (Animation, Action). Manga Entertainment. 1 October 1999. Retrieved 12 October 2023 – via IMDb.

- ^ Michelle, Reis (interviewee) (2006) [1992]. The Wicked City (1992 film). Pathé.

External links

[edit]- Wicked City at IMDb

- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Wicked City at AllMovie

- Wicked City at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- 1987 films

- 1987 anime films

- 1987 directorial debut films

- 1987 fantasy films

- 1987 horror films

- 1987 thriller films

- 1980s exploitation films

- Animated films about parallel universes

- Animated films based on Japanese novels

- Animated films set in Tokyo

- Animated thriller films

- Dark fantasy anime and manga

- Demons in film

- Erotic horror films

- Films about rape

- Films directed by Yoshiaki Kawajiri

- Japanese action horror films

- Japanese adult animated films

- Japanese animated fantasy films

- Japanese animated horror films

- Japanese dark fantasy films

- Japanese horror thriller films

- Japanese neo-noir films

- Madhouse (company)

- Manga Entertainment

- Sentai Filmworks

- Thriller anime and manga