William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst | |

|---|---|

Hearst in 1906, photograph by James E. Purdy | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 11th district | |

| In office March 4, 1903 – March 4, 1907 | |

| Preceded by | William Sulzer |

| Succeeded by | Charles V. Fornes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 29, 1863 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 14, 1951 (aged 88) Beverly Hills, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic Party (1896–1935) Independence Party (1905–1910) Municipal Ownership League (1904–05) |

| Spouse | Millicent Willson Hearst (1903–1951) |

| Relations | Patty Hearst, granddaughter Anne Hearst, granddaughter Lydia Hearst-Shaw, great-granddaughter Amanda Hearst, great-granddaughter Marion Davies, mistress |

| Children | George Randolph Hearst (1904–1972) William Randolph Hearst, Jr. (1908–1993) John Randolph Hearst (1910–1958) Randolph Apperson Hearst (1915–2000) David Whitmire Hearst (1915–1986) |

| Parent(s) | Phoebe Apperson Hearst, mother George Hearst, father |

| Residence(s) | Hearst Castle San Simeon, California |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Occupation | Businessman & publisher |

| Signature | |

William Randolph Hearst (/hɜːst/;[1] April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher who built the nation's largest newspaper chain and whose methods profoundly influenced American journalism.[2] Hearst entered the publishing business in 1887 after taking control of The San Francisco Examiner from his father. Moving to New York City, he acquired The New York Journal and engaged in a bitter circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer's New York World that led to the creation of yellow journalism—sensationalized stories of dubious veracity. Acquiring more newspapers, Hearst created a chain that numbered nearly 30 papers in major American cities at its peak. He later expanded to magazines, creating the largest newspaper and magazine business in the world.

He was twice elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives, and ran unsuccessfully for Mayor of New York City in 1905 and 1909, for Governor of New York in 1906, and for Lieutenant Governor of New York in 1910. Nonetheless, through his newspapers and magazines, he exercised enormous political influence, and was famously blamed for pushing public opinion with his yellow journalism type of reporting leading the United States into a war with Spain in 1898.

His life story was the main inspiration for the development of the lead character in Orson Welles's film Citizen Kane.[3] His mansion, Hearst Castle, on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean near San Simeon, California, halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, was donated by the Hearst Corporation to the state of California in 1957, and is now a State Historical Monument and a National Historic Landmark, open for public tours. Hearst formally named the estate La Cuesta Encantada ("The Enchanted Slope"), but he usually just called it "the ranch."

Ancestry and early life

William R. Hearst was born in San Francisco to millionaire mining engineer, goldmine owner and U.S. senator (1886–91) George Hearst and his wife Phoebe Apperson Hearst.

His paternal great-grandfather was John Hearst, of Scots-Irish origin, who emigrated to America with his wife and six children in 1766 and settled in South Carolina. Their immigration to South Carolina was spurred in part by the colonial government's policy that encouraged the immigration of Irish Protestants.[4] The names "John Hearse" and "John Hearse Jr." appear on the council records of October 26, 1766, being credited with meriting 400 and 100 acres (1.62 and 0.40 km2) of land on the Long Canes (in what became Abbeville District), based upon 100 acres (0.40 km2) to heads of household and 50 acres (200,000 m2) for each dependent of a Protestant immigrant. The "Hearse" spelling of the family name never was used afterward by the family members themselves, or any family of any size. A separate theory purports that one branch of a "Hurst" family of Virginia (originally from Plymouth Colony) moved to South Carolina at about the same time and changed the spelling of its surname of over a century to that of the emigrant Hearsts.[5] Hearst's mother, née Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson, was of Irish ancestry; her family came from Galway.[6] She was the first woman regent of University of California, Berkeley, funded many anthropological expeditions and founded the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology.

Following preparation at St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire, Hearst enrolled in the Harvard College class of 1885. While there he was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon, the A.D. Club (a Harvard Final club), the Hasty Pudding Theatricals, and of the Harvard Lampoon before being expelled for antics ranging from sponsoring massive beer parties in Harvard Square to sending pudding pots used as chamber pots to his professors (their images were depicted within the bowls).[7]

Publishing business

Searching for an occupation, in 1887 Hearst took over management of a newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, which his father received in 1880 as repayment for a gambling debt.[8] Giving his paper a grand motto, "Monarch of the Dailies," he acquired the best equipment and the most talented writers of the time, including Ambrose Bierce, Mark Twain, Jack London, and political cartoonist Homer Davenport. A self-proclaimed populist, Hearst went on to publish stories of municipal and financial corruption, often attacking companies in which his own family held an interest. Within a few years, his paper dominated the San Francisco market.

New York Morning Journal

Early in his career at the San Francisco Examiner, Hearst envisioned running a large newspaper chain, and "always knew that his dream of a nation-spanning, multi-paper news operation was impossible without a triumph in New York."[9] In 1895, with the financial support of his mother, he bought the failing New York Morning Journal, hiring writers like Stephen Crane and Julian Hawthorne and entering into a head-to-head circulation war with Joseph Pulitzer, owner and publisher of the New York World, from whom he "stole" Richard F. Outcault, the inventor of color comics, and all of Pulitzer's Sunday staff as well.[10] Another prominent hire was James J. Montague, who came from the Portland Oregonian and started his well-known "More Truth Than Poetry" column at the Hearst-owned New York Evening Journal.[11]

When Hearst purchased the "penny paper," so called because its copies sold for only a penny apiece, the Journal was competing with New York's 16 other major dailies, with a strong focus on Democratic Party politics.[12] Hearst imported his best managers from the San Francisco Examiner and "quickly established himself as the most attractive employer" among New York newspapers. He was generous, paid more than his competitors, gave credit to his writers with page-one bylines, and was unfailingly polite, unassuming, "impeccably calm," and indulgent of "prima donnas, eccentrics, bohemians, drunks, or reprobates so long as they had useful talents."[13]

Hearst's activist approach to journalism can be summarized by the motto, "While others Talk, the Journal Acts."

Yellow Journalism and rivalry with the New York World

The New York Journal and its chief rival, the New York World, mastered a style of popular journalism that came to be derided as "Yellow Journalism," after Outcault's Yellow Kid comic. Pulitzer's World had pushed the boundaries of mass appeal for newspapers through bold headlines, aggressive news gathering, generous use of cartoons and illustrations, populist politics, progressive crusades, an exuberant public spirit, and dramatic crime and human-interest stories. Hearst's Journal used the same recipe for success, forcing Pulitzer to drop the price of the World from 2 cents to a penny. Soon the two papers were locked in a fierce, often spiteful competition for readers in which both papers would spend large sums of money and see huge gains in circulation.

Within a few months of purchasing the Journal, Hearst would hire away Pulitzer's three top editors: Sunday editor Morrill Goddard, who greatly expanded the scope and appeal of the American Sunday newspaper, Solomon Carvalho, and a young Arthur Brisbane, who would become managing editor of the Hearst newspaper empire, and a legendary columnist. Contrary to popular assumption, they were not lured away by higher pay—rather, each man had grown tired of both the temperamental, domineering Pulitzer and the paranoid, back-biting office politics which he encouraged.[14]

While Hearst's many critics attribute the Journal's incredible success to cheap sensationalism, as Kenneth Whyte noted in The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise Of William Randolph Hearst, "The Journal was a demanding, sophisticated paper by contemporary standards. Rather than racing to the bottom, he [Hearst] drove the Journal and the penny press upmarket."[15] Though yellow journalism would be much maligned, "All good yellow journalists...sought the human in every story and edited without fear of emotion or drama. They wore their feelings on their pages, believing it was an honest and wholesome way to communicate with readers." But, as Whyte pointed out, "This appeal to feelings is not an end in itself...[they believed] our emotions tend to ignite our intellects: a story catering to a reader's feelings is more likely than a dry treatise to stimulate thought."[16]

The two papers would finally declare a truce in late 1898, after both papers lost vast amounts of money covering the Spanish-American War. Indeed, Hearst probably lost several million dollars in his first three years as publisher of the Journal. (Actual figures are impossible to verify.) But the paper began turning a profit after it settled its rivalry with the World.[17]

Politics

Under Hearst, the Journal remained loyal to the populist wing of the Democratic Party, and was the only major publication in the East to support William Jennings Bryan and Bimetallism in 1896. Their coverage of that historic election was probably the most important of any newspaper in the country, exposing both the unprecedented role of money in the Republican campaign and the dominating role played by William McKinley's political and financial manager, Mark Hanna, the first national party 'boss' in American history.[18] Only a year after taking over the paper, Hearst could boast that sales of the Journal's post-election issue (including the Evening and German-language editions) topped 1.5 million, a record "unparalleled in the history of the world."[19]

The Journal's political coverage, however, was not entirely one-sided. While most editors of the time "believed their papers should speak with one voice on political matters," Hearst "helped to usher in the multi-perspective approach we identify with the modern op-ed page."[20]

Hearst used the power of his newspaper chain to editorialize for the passage of the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act after the American Bar Association had approved of it in 1932. Dr. William C. Woodward, legislative counsel of the American Medical Association, suggested the support of the Hearst papers would ensure the passage of the act.[21] Dr. Woodward testified before the House Ways and Means Committee that although "(t)here is no evidence to show whether or not (cannabis usage) has been (increasing)" in his opinion "(n)ewspaper exploitation of the habit has done more to increase it than anything else."[22] In 1937 Hearst used his papers to push for the passage of the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. Hearst was commended by a conference of judges, lawyers and politicians for "pioneering the national fight against dope" for the anti-marijuana editorials and articles in his papers.[21] In later years, however, Hearst's "pioneering" has been widely viewed as mere pandering to the corporate interests of DuPont, as well as protecting his own substantial forest products interests against the industrial use of hemp.[23][24] Hearst's editorial efforts with respect to the ban on hemp coincide with the court-ordered reorganization of the Hearst corporation's non-publishing assets, mainly mining and forest products, in 1937.[25]

The Spanish-American War

The Morning Journal's daily circulation would routinely climb above the 1 million mark after the sinking of the Maine and U.S. entry into the Spanish-American War, a war that some dubbed, "The Journal's War" due to the paper's immense influence in provoking American outrage against Spain.[26] Much of the coverage leading up to the war, beginning with the outbreak of the Cuban Revolution in 1895, was tainted by rumor, propaganda, and sensationalism, with the "yellow" papers regarded as the worst offenders. Indeed, the Journal and other New York newspapers were so one-sided and full of errors in their reporting that coverage of the Cuban crisis and the ensuing Spanish-American War is often cited as one of the most significant milestones in the rise of yellow journalism's hold over the mainstream media.[27] Huge headlines in the Journal assigned blame for the Maine's destruction on sabotage – based on no actual evidence – and stoked public outrage and indignation against Spain.

Nevertheless, the Journal's crusade against Spanish rule in Cuba was not due to mere jingoism, although "the democratic ideals and humanitarianism that inspired their coverage are largely lost to history," as are their "heroic efforts to find the truth on the island under unusually difficult circumstances."[28] The Journal's journalistic activism in support of the Cuban rebels, rather, was centered around Hearst's political and business ambitions.[27] An apocryphal story centers around illustrator Frederic Remington, sent by Hearst to Cuba to cover the Cuban War of Independence.[27] In this telling, Remington telegrammed Hearst to tell him all was quiet in Cuba and "There will be no war," and Hearst responded, "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." Some historians now believe that no such telegrams ever were sent.[29][30]

Hearst was personally dedicated to the cause of the Cuban rebels, and the Journal did some of the most important and courageous reporting on the conflict – as well as some of the most sensationalized. In fact, their stories on the Cuban rebellion and Spain's atrocities on the island – many of which turned out to be untrue[27] – were motivated primarily by outrage at Spain's brutal policies on the island, which led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent Cubans. The most well-known story involved the imprisonment and release of Cuban prisoner Evangeline Cisneros.[27][31]

While Hearst and the yellow press did not directly cause America's war with Spain, they did inflame public opinion to a fever pitch, which was a major influence in Pres. McKinley's decision to use force against Spain. Furthermore, congressmen and other public officials of the time received most of their information from newspapers, and the Journal, the World, and the more respectable New York Herald had by far the most informative, extensive, and influential coverage.

Hearst sailed to Cuba with a small army of Journal reporters to cover the Spanish-American War in person, bringing along portable printing equipment, which was used to print a single edition newspaper in Cuba after the fighting had ended. Two of the Journal's correspondents, James Creelman and Edward Marshall, were wounded in the fighting. A leader of the Cuban rebels, Gen. Calixto García, gave Hearst a Cuban flag that had been riddled with bullets as a gift, in appreciation of Hearst's major role in Cuba's liberation.[32]

Meeting with William Thomas Stead

A year before the Spanish-American War,[33] William Thomas Stead wrote of his crossing the Atlantic to meet with Mr. Hearst. Stead taught Hearst about Government By Journalism, and praised him for his role in creating the Spanish-American War by saying "He had found his soul".[34][35]

Expansion

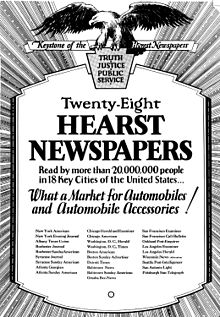

In part to aid in his political ambitions, Hearst opened newspapers in some other cities, among them Chicago, Los Angeles and Boston. The creation of his Chicago paper was requested by the Democratic National Committee, and Hearst used this as an excuse for Phoebe Hearst to transfer him the necessary start-up funds. By the mid-1920s he had a nation-wide string of 28 newspapers, among them the Los Angeles Examiner, the Boston American, the Atlanta Georgian, the Chicago Examiner, the Detroit Times, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Washington Times, the Washington Herald, and his flagship the San Francisco Examiner.

Hearst also diversified his publishing interests into book publishing and magazines; several of the latter are still in circulation, including such periodicals as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Town and Country, and Harper's Bazaar.

In 1924 he opened the New York Daily Mirror, a racy tabloid frankly imitating the New York Daily News, Among his other holdings were two news services, Universal News and International News Service, or INS, the latter of which he founded in 1909.[36] He also owned INS companion radio station WINS in New York); King Features Syndicate, which still owns the copyrights of a number of popular comics characters; a film company, Cosmopolitan Productions; extensive New York City real estate; and thousands of acres of land in California and Mexico, along with timber and mining interests.

Hearst's father, US Senator George Hearst, had acquired land in the Mexican state of Chihuahua after receiving advance notice that Geronimo – who had terrorized settlers in the region – had surrendered. George Hearst was able to buy 670,000 acres (270,000 ha),[37] the Babicora Ranch, at 20–40 cents each because only he knew that they had become much more secure.[38] George Hearst was on friendly terms with Porfirio Díaz, the Mexican dictator, who helped him settle boundary disputes profitably. The ranch was expanded to nearly 1,000,000 acres (400,000 ha) by George Hearst, then by Phoebe Hearst after his death.[38][39] The younger Hearst was at Babicora as early as 1886, when, as he wrote to his mother, "I really don't see what is to prevent us from owning all Mexico and running it to suit ourselves."[37][40] During the Mexican Revolution, his mother's ranch was looted by irregulars under Pancho Villa. Babicora was then occupied by Carranza's forces. Phoebe Hearst willed the ranch to her son in 1919.[41] Babicora was sold to the Mexican government for $2.5 million in 1953, just two years after Hearst's death.[42]

Hearst promoted writers and cartoonists despite the lack of any apparent demand for them by his readers. The press critic A. J. Liebling reminds us how many of Hearst's stars would not have been deemed employable elsewhere. One Hearst favorite, George Herriman, was the inventor of the dizzy comic strip Krazy Kat; not especially popular with either readers or editors at the time of its initial publication, it is now considered by many to be a classic, a belief once held only by Hearst himself.

Two months before the Wall Street Crash of 1929, he became one of the sponsors of the first round-the-world voyage in an airship, the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin from Germany. His sponsorship was conditional on the trip starting at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, NJ, so the ship's captain, Dr. Hugo Eckener, first flew the Graf Zeppelin across the Atlantic from Germany to pick up Hearst's photographer and at least three Hearst correspondents. One of them, Grace Marguerite Hay Drummond-Hay, by that flight became the first woman to travel around the world by air.[43]

The Hearst news empire reached a circulation and revenue peak about 1928, but the economic collapse of the Great Depression and the vast over-extension of his empire cost him control of his holdings. It is unlikely that the newspapers ever paid their own way; mining, ranching and forestry provided whatever dividends the Hearst Corporation paid out. When the collapse came, all Hearst properties were hit hard, but none more so than the papers; Furthermore, his now-conservative politics, increasingly at odds with those of his readers, only worsened matters for the once great Hearst media chain. Having been refused the right to sell another round of bonds to unsuspecting investors, the shaky empire tottered. Unable to service its existing debts, Hearst Corporation faced a court-mandated reorganization in 1937. From that point, Hearst was reduced to being merely another employee, subject to the directives of an outside manager.[25] Newspapers and other properties were liquidated, the film company shut down; there was even a well-publicized sale of art and antiquities. While World War II restored circulation and advertising revenues, his great days were over. Hearst died of a heart attack in 1951, aged eighty-eight, in Beverly Hills, California, and is buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California.

The Hearst Corporation continues to this day as a large, privately held media conglomerate based in New York City.

Involvement in politics

A Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives, in which he served two terms, covering the period from 1903 to 1907, he narrowly failed in attempts to become mayor of New York City in both 1905 and 1909 and governor of New York in 1906, nominally remaining a Democrat while also creating the Independence Party. He was defeated for the governorship by Charles Evans Hughes. Hearst's unsuccessful campaigns for office after his tenure in the House Of Representatives earned him the unflattering but short-lived nickname of "William 'Also-Randolph' Hearst."[citation needed]

His defeat in the New York City mayoral election (in which he ran under a short-lived third party of his own creation, the Municipal Ownership League), is widely attributed to the efforts of Tammany Hall to derail Hearst's campaign. Tammany, the then dominant Democratic organization in New York City, was infamous at the time for its widespread corruption, and was said to have used every dirty trick in the book to defame Hearst. He also sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1904, but found that his support for William Jennings Bryan in previous years was not reciprocated, and Bryan did not endorse him. The conservative wing of the party was ascendant and nominated Judge Alton B. Parker instead. An opponent of the British Empire, Hearst opposed American involvement in the First World War and attacked the formation of the League of Nations. Hearst's last bid for office came in 1922 when he was backed by Tammany Hall leaders for the U.S. Senate nomination in New York. Al Smith vetoed this, earning the lasting enmity of Hearst. Although Hearst shared Smith's opposition to Prohibition, he swung his papers behind Herbert Hoover in the 1928 presidential election. Hearst's support for Franklin D. Roosevelt at the 1932 Democratic National Convention, via his allies William Gibbs McAdoo and John Nance Garner, can also be seen as part of his vendetta against Smith, who was an opponent of Roosevelt's at that convention.

Hearst's reputation triumphed in the 1930s as his political views changed. In 1932, he was a major supporter of Roosevelt. His newspapers energetically supported the New Deal throughout 1933 and 1934. Hearst broke with FDR in spring 1935 when the President vetoed the Patman Bonus Bill. Hearst papers carried the old publisher's rambling, vitriolic, all-capital-letters editorials, but he no longer employed the energetic reporters, editors, and columnists who might have made a serious attack. His newspaper audience was the same working class that Roosevelt had swept by three-to-one margins in the 1936 election. In 1934 after checking with Jewish leaders to ensure a visit would be to their benefit, Hearst visited Berlin to interview Adolf Hitler. When Hitler asked why he was so misunderstood by the American press, Hearst retorted, "Because Americans believe in democracy, and are averse to dictatorship."[44] Hearst's Sunday papers ran columns without rebuttal by Hermann Göring and Dr. Alfred Rosenberg.[45]

Personal life

In 1903, Hearst married Millicent Veronica Willson (1882–1974), a 21-year-old chorus girl, in New York City. Evidence in Louis Pizzitola's book Hearst Over Hollywood indicates that Millicent's mother Hannah Willson ran a Tammany-connected and -protected brothel quite near the headquarters of political power in New York City at the turn of the 20th century. Millicent bore him five sons: George Randolph Hearst, born on April 23, 1904; William Randolph Hearst, Jr., born on January 27, 1908; John Randolph Hearst, born in 1910; and twins Randolph Apperson Hearst and David Whitmire (né Elbert Willson) Hearst, born on December 2, 1915. Hearst was the grandfather of Patricia "Patty" Hearst, widely known for being kidnapped by and then joining the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974 (her father was Randolph Apperson Hearst, Hearst's fourth son).

Marion Davies

Conceding an end to his political hopes, Hearst became involved in an affair with popular film actress and comedienne Marion Davies (1897–1961), former mistress of his friend Paul Block,[46] and from about 1919, he lived openly with her in California. The affair dominated Davies's life. Millicent separated from Hearst in the mid-1920s after tiring of his longtime affair with Davies, but the couple remained legally married until Hearst's death. Millicent built an independent life for herself in New York City as a leading philanthropist, was active in society, and created the Free Milk Fund for the poor in 1921. After the death of Patricia Lake, Davies's supposed niece, it was speculated that Lake was in fact Hearst's daughter by Davies.[citation needed]

California properties

Beginning in 1919, Hearst began to build Hearst Castle, which he was destined never to complete, on a 240,000 acres (97,000 hectares) ranch at San Simeon, California, which he furnished with art, antiques and entire rooms brought from the great houses of Europe. He also used the ranch for an Arabian horse breeding operation. San Simeon was also used in the 1960 film Spartacus as the estate of Marcus Licinius Crassus (played by Laurence Olivier).

He also had a property on the McCloud River in Siskiyou County, in far northern California, called Wyntoon.[47] Wyntoon was designed by famed architect Julia Morgan, who also designed Hearst Castle and worked in collaboration with William J. Dodd on a number of other projects.

In 1947, Hearst paid $120,000 for an H-shaped Beverly Hills mansion on 3.7 acres three blocks from Sunset Boulevard. This home, known as Beverly House, was once perhaps the "most expensive" private home in the U.S., valued at $165 million (£81.4 million). It has 29 bedrooms, three swimming pools, tennis courts, its own cinema and a nightclub. Lawyer and investor Leonard Ross has owned it since 1976. The estate went on the market for $95 million at the end of 2010.[48] The property had not sold by 2012 but was then listed at a significantly increased asking price of $135 million.[citation needed] The Beverly House, as it has come to be known, has some cinematic connections. It was the setting for the gruesome scene in the film The Godfather depicting a horse's severed head in the bed of film-producer, Jack Woltz. The character was head of a film company called International, the name of Hearst's early film company.[49] According to Hearst Over Hollywood. John and Jacqueline Kennedy stayed at the house for part of their honeymoon. They watched their first film together as a married couple in the mansion's cinema. It was a Hearst-produced film from the 1920s.

In the early 1890s, Hearst began building a mansion on the hills overlooking Pleasanton, California on land purchased by his father a decade earlier. Hearst's mother took over the project, hired Julia Morgan to finish it as her home, and named it Hacienda del Pozo de Verona. [50] After her death, it served as the clubhouse for Castlewood Country Club from 1925 to 1969, when it was destroyed in a massive fire.

Art collection

Hearst was renowned for his extensive collection of art from around the globe and through the centuries. Most notable in his collection were his Greek vases, Spanish and Italian furniture, Oriental carpets, Renaissance vestments, an extensive library with many books signed by their authors, and paintings and statues from all over. In addition to collecting pieces of fine art, he also gathered manuscripts, rare books, and autographs.[51]

His house was often visited by varied celebrities and politicians as guests who stayed in rooms furnished with pieces of antique furniture and decorated with artwork by several famous artists.[51]

Beginning in 1937, Hearst began selling some of his art collection to help relieve the burden he had suffered from the depression. The first year he sold 11 million dollars worth. In 1941 he put about 20,000 items up for sale that were a good indication of his wide and varied tastes. Included in the items he put up for sale were paintings by van Dyke, crosiers, chalices, Charles Dickens's sideboard, pulpits, stained glass, arms and armor, George Washington's waistcoat, and Thomas Jefferson's Bible. Despite the magnitude of these sales, when Hearst Castle was finally given to the State of California there were still enough items for the whole house to be considered as a museum.[51]

St. Donat's Castle

After seeing photographs of St. Donat's Castle in Country Life Magazine, Hearst bought the Welsh Vale of Glamorgan property and revitalized it in 1925 as a love gift to Davies.[52] The Castle was restored by Hearst, who spent a fortune buying entire rooms from castles and palaces in Europe. The Great Hall was bought from the Bradenstoke Priory in Wiltshire and reconstructed brick by brick in its current site at St. Donat's Castle. The road haulage work was carried out by freight brokers Holme & Simpson, later North British Transport Ltd. From the Bradenstoke Priory he also bought and removed the guest house, Prior's lodging, and great tithe barn; of these, some of the materials became the St. Donat's banqueting hall, complete with a sixteenth-century French chimney-piece and windows; also used were a fireplace dated to c. 1514 and a fourteenth-century roof, which became part of the Bradenstoke Hall, despite this use being questioned in Parliament. Hearst built 34 green and white marble bathrooms for the many guest suites in the castle, and completed a series of terraced gardens which survive intact today. Hearst and Davies spent much of their time entertaining and held a number of lavish parties, the guests at which included Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Winston Churchill, and a young John F. Kennedy. Upon visiting St. Donat's, George Bernard Shaw was quoted as saying: "This is what God would have built if he had had the money." When Hearst died, the castle was bought and is still owned and used by Atlantic College, an international boarding school.[citation needed]

The Family Club

Once a decorated member of the Bohemian Club, Hearst branched off to form his own private club, The Family. The Family keeps a clubhouse in San Francisco and a rural retreat in Woodside, California.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

In 1947, Hearst left his San Simeon estate to seek medical care, which was unavailable in the remote location. He died in Beverly Hills on August 14, 1951, at the age of 88. He was interred in the Hearst family mausoleum at the Cypress Lawn Cemetery in Colma, California. Like their father, none of Hearst's five sons succeeded in graduating from college,[53] but they all followed their father into the media business, and Hearst's namesake, William Randolph, Jr., became a Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper reporter.

Criticism

As Martin Lee and Norman Solomon noted in their 1990 book Unreliable Sources, Hearst "routinely invented sensational stories, faked interviews, ran phony pictures and distorted real events." This approach came to be known as "yellow journalism," so named after The Yellow Kid, a character in the New York World's color comic strip Hogan's Alley.

Hearst's use of yellow journalism techniques in his New York Journal to whip up popular support for U.S. military adventurism in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines in 1898 was also criticized in Upton Sinclair's 1919 book, The Brass Check: A Study of American Journalism. According to Sinclair, Hearst's newspaper employees were "willing by deliberate and shameful lies, made out of whole cloth, to stir nations to enmity and drive them to murderous war." Sinclair also asserted that in the early 20th century Hearst's newspapers lied "remorselessly about radicals," excluded "the word Socialist from their columns" and obeyed "a standing order in all Hearst offices that American Socialism shall never be mentioned favorably." In addition, Sinclair charged that Hearst's "Universal News Bureau" re-wrote the news of the London morning papers in the Hearst office in New York and then fraudulently sent it out to American afternoon newspapers under the by-lines of imaginary names of non-existent "Hearst correspondents" in London, Paris, Venice, Rome, Berlin, etc. Another critic, Ferdinand Lundberg, extended the criticism in Imperial Hearst (1936), charging that Hearst papers accepted payments from abroad to slant the news. After the war, a further critic, George Seldes, repeated the charges in Facts and Fascism (1947). Also, biographer A. Scott Berg notes that in the late 1920s Charles Lindbergh refused Hearst's very generous offer to sponsor him in a motion-picture career, in part because the famous aviator had little respect for the content and tone of Hearst's publications.[54]

Although he frequently lambasted magnates such as J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts in public, in private Hearst entered into partnership with them in lucrative ventures such as the Cerro de Pasco mines in Peru.[45]

In fiction

Citizen Kane

Citizen Kane is one of the most influential films of all time and is loosely based on Hearst's life. Welles and co-writer Herman J. Mankiewicz created Kane as a composite character of multiple men, among them Harold McCormick, Samuel Insull and Howard Hughes. Hearst, enraged at the idea of Citizen Kane being a thinly disguised and very unflattering portrait of him, used his massive influence and resources in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent the film from being released - all without his ever even having seen it. Welles and the studio RKO Pictures resisted the pressure, but Hearst and his Hollywood friends ultimately succeeded in pressuring theater chains to limit showings of Citizen Kane,[55] resulting in mediocre box-office numbers and seriously harming Welles's career.

Nearly sixty years later, HBO offered a fictionalized version of Hearst's efforts in its picture RKO 281. Hearst is portrayed in the film by James Cromwell.

Citizen Kane has twice been ranked No. 1 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (1998 and 2007).

Other works

- The character of Gail Wynand in Ayn Rand's 1943 novel The Fountainhead is based on Hearst.[citation needed]

- Hearst is a major character in Gore Vidal's Narratives of Empire historic novel series.

- The Cat's Meow is a 2001 drama film inspired by the mysterious death of film mogul Thomas H. Ince. The film takes place aboard publisher William Randolph Hearst's yacht on a weekend cruise celebrating Ince's 42nd birthday in November 1924.

- The novel Goliath (2011) by Scott Westerfeld depicts Hearst in World War I.

- Hearst is portrayed during the time of the Roscoe Arbuckle trial in the 2009 novel Devil's Garden by Ace Atkins

- The character Kristjan Benediksson the main protangonist in Olaf Olafsson's 2003 novel Walking into the Night, is a fictional butler to William Randolph Hearst.

See also

- Josephine Terranova

- Hearst Ranch

- History of American newspapers

- Santa Maria de Ovila

- St. Bernard de Clairvaux Church

- The Hacienda (Milpitas Ranchhouse)

- Warwick New York Hotel

References

- ^ "Hearst". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Obituary Variety, August 15, 1951.

- ^ The Battle Over Citizen Kane, PBS.

- ^ Kyle J. Betit. "Scots-Irish in Colonial America". The Irish Times. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Carlson 2007, pp. 3–4

- ^ Robinson 1991, p. 33

- ^ The American Pageant: A History of the Republic, Thirteenth edition, Advanced Placement Edition, copyright 2006

- ^ "Hearst Castle National Park Service". Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 463

- ^ "The Press: The King Is Dead". Time. August 20, 1951.

- ^ "James Montague, Versifier, Is Dead," New York Times, December 17, 1941.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 48

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 116–17

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 100–106, 110–111, 346–348

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 92

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 314

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 455, 463

- ^ Whyte 2009, pp. 164–65, 178

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 193

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 163

- ^ a b Charles H. Whitebread and Richard J. Bonnie (1972). The Marihuana Consensus: A History of American Marihuana Prohibition. University of Virginia Law School. pp. 100–101.

- ^ Richard J Bonnie (1971). "CHAPTER VIII Nonchalance on Capitol Hill". The Marihuana Conviction. Retrieved July 15, 2014.Transcript of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 hearing, 27 April 1937.

- ^ French, Laurence; Manzanárez, Magdaleno (2004). NAFTA & neocolonialism: comparative criminal, human & social justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7

- ^ Peet, Preston. (2004). Under The Influence: The Disinformation Guide To Drugs. Consortium Book Sales & Dist. p.55. ISBN 1-932857-00-1, 9781932857009.

- ^ a b "The Press: American's End". Time. July 5, 1937.

- ^ Whyte 2009

- ^ a b c d e PBS. "Crucible of Empire:The Spanish American War". Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 260

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (2003). Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies. p. 72.

- ^ Campbell, W. Joseph (December 2001). "You Furnish the Legend, I'll Furnish the Quote". American Journalism Review.

- ^ William Thomas Stead. "A Romance of the Pearl of the Antilles". Review of Reviews.

- ^ Whyte 2009, p. 427

- ^ Mooney, Bel (December 1908). "A Character Sketch of William Randolph Hearst, by William Thomas Stead". London: Review of Reviews. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "W. Randolf Hearst". Attackingthedevil.co.uk. December 30, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

He began the battle against the Trusts; he made the Spanish-American war. For weal or for woe Mr. Hearst had found his soul; for weal or for woe he had discovered his chart and engaged his pilot, and from that day to this he has steered a straight course, with no more tackings than were necessary to avoid the fury of the storm. Some years afterwards I met Mr. Hearst in Paris. He recalled our first conversation, and said, "I never had a talk with anyone which made so deep a dint in life.

- ^ Eckley, Grace (2007). Maiden Tribute. Xlibris Corporation. pp. Chapter 11. ISBN 978-1425727086.

- ^ Time staff reporter (June 2, 1958). "The Press: New York, May 24 (UPI)". TIME. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Nasaw, David (2001). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-618-15446-9.

- ^ a b Brechin, Gray A. (2006). Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin. California Studies in Critical Human Geography. Vol. 3. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-520-25008-7.

- ^ Robinson 1991, p. 89

- ^ Gonzales, Michael J. (2002). The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1940 (1st ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 8.

- ^ Procter, Ben H. (2007). William Randolph Hearst: final edition, 1911–1951. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-19-532534-6.

- ^ "Mexico: End of An Empire". Time. September 7, 1953.

- ^ "Los Angeles to Lakehurst". Time. September 9, 1929.

- ^ Conradi, Peter (June 22, 2004). Hitler's Piano Player. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7867-1283-0.

- ^ a b Brechin, "Imperial San Francisco," 1999, University of California Press.

- ^ Toledo Blade: "Paul Block: Story of success" BY JACK LESSENBERRY January 9, 2013

- ^ Wyntoon is located at approximately 41°11′21″N 122°03′58″W / 41.18917°N 122.06611°W

- ^ Brenoff, Ann (September 20, 2010). "Hearst Estate in Beverly Hills Marked Down: Is It a Bargain at $95M?|AOL Real Estate". Housingwatch.com. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ ""Most expensive" U.S. home on sale". BBC News. July 11, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ http://www.castlewoodcc.org/default.aspx?p=DynamicModule&pageid=254060&ssid=113155&vnf=1

- ^ a b c Seely, Jana. "The Hearst Castle, San Simeon: The Diverse Collection of William Randolph Hearst". Southeastern Antiquing and Collecting Magazine.

- ^ Bevan, Nathan (August 3, 2008). "Lydia Hearst is queen of the castle". Wales On Sunday. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ Nasaw, David (2000). The Chief The Life of William Randolph Hearst. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 357–358. ISBN 0-395-82759-0.

- ^ Berg, A. Scott (1998). Lindbergh. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0-399-14449-8.

- ^ Howard, James. The complette films of Orson Welles. New York, Citadell Press, 1991, p. 47.

Further reading

- Carlson, Oliver (2007). Hearst – Lord of San Simeon. Read Books. ISBN 1-4067-6684-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Marion (1975). The Times We Had: Life with William Randolph Hearst. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-672-52112-1.

- Duffus, Robert L. (September 1922). "The Tragedy Of Hearst". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV: 623–631. Retrieved August 4, 2009.

- Frazier, Nancy (2001). William Randolph Hearst: Modern Media Tycoon. Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press. ISBN 1-56711-512-8.

- Hearst, William Randolph, Jr. (1991). The Hearsts: Father and Son. Niwot, CO: Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 1-879373-04-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Levkoff, Mary L. (2008). Hearst: The Collector. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc. ISBN 0-8109-7283-2.

- Liebling, A.J. (1964). The Press. New York: Pantheon.

- Lundberg, Ferdinand (1936). Imperial Hearst: A Social Biography. New York: Equinox Corporative Press.

- Nasaw, David (2000). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-82759-0.

- Pizzitola, Louis (2002). Hearst Over Hollywood: Power, Passion, and Propaganda in the Movies. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11646-2.

- Procter, Ben H. (1998). William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511277-6.

- Procter, Ben H. (2007). William Randolph Hearst: The Later Years, 1911–1951. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-532534-6.

- Reardon, David (2003). "William Hearst". American History: Post-Civil War to the Present. Worldview Software.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)( worldviewsoftware.com Must pay to view. ) - Robinson, Judith (1991). The Hearsts: An American dynasty. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-383-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - St. Johns, Adela Rogers (1969). The Honeycomb. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Seldes, George (1947). Facts and Fascism. New York: In Fact.

- Swanberg, W.A. (1961). Citizen Hearst. New York: Scribner.

- Whyte, Kenneth (2009). The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Berkeley: Counterpoint.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilkerson, Marcus M. (1932). Public Opinion and the Spanish-American War: A Study in War Propaganda. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Winkler, John K. (1955). William Randolph Hearst: A New Appraisal. New York: Hastings House.

- "Hearst, William Randolph". Compton's encyclopedia. Compton's Learning Company. 1994. p. 96.

External links

- Hearst the Collector at LACMA

- United States Congress. "William Randolph Hearst (id: H000429)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- William Randolph Hearst biography, via zpub.com

- The William Randolph Hearst Art Archive at Long Island University

- Guide to the William Randolph Hearst Papers at The Bancroft Library

- San Simeon, the Hearst Castle

- William Randolph Hearst at IMDb

- Original Bureau of Investigation Document Online: William Randolph Hearst

- FBI file on William Randolph Hearst, Sr.

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 1863 births

- 1951 deaths

- American media company founders

- American mass media owners

- American newspaper publishers (people)

- American socialites

- California Democrats

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Harvard Lampoon people

- Harvard University alumni

- Hearst family

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York

- New York Democrats

- News agency founders

- Businesspeople from New York

- Businesspeople from San Francisco, California

- People of the Spanish–American War

- Progressive Era in the United States

- St. Paul's School (Concord, New Hampshire) alumni

- The San Francisco Examiner people

- United States Independence Party politicians

- United States presidential candidates, 1904

- Politicians from San Francisco, California

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- Old Right (United States)