Wind power: Difference between revisions

m BOT - Reverted edits by Link0232 {possible vandalism} to last version by Geologyguy. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:Windenergy.jpg|thumb|300px|An example of a [[wind turbine]]. This 3 bladed turbine is the most common design of modern wind turbines because it minimizes forces related to fatigue.]] |

[[Image:Windenergy.jpg|thumb|300px|An example of a [[wind turbine]]. This 3 bladed turbine is the most common design of modern wind turbines because it minimizes forces related to fatigue.]] |

||

{{renewable energy sources}} |

{{renewable energy sources}} Megan jones I would like to to apoligize for staring at your tits sorry |

||

'''Wind power''' is the conversion of wind energy into useful form, such as electricity, using [[wind turbine]]s. In [[windmill]]s, wind energy is directly used to crush grain or to pump water. At the end of 2006, worldwide capacity of wind-powered generators was 73.9 [[gigawatt]]s.<ref name="wwindea"> [http://www.wwindea.org/home/images/stories/pdfs/pr_statistics2006_290107.pdf World Wind Energy Association Statistics] (PDF).</ref> Although wind currently produces just over 1% of world-wide electricity use, it accounts for approximately 19% of electricity production in [[Wind power in Denmark|Denmark]], 9% in [[Wind power in Spain|Spain]] and [[Wind power in Portugal|Portugal]], and 6% in [[Wind power in Germany|Germany]] and the [[Wind power in Ireland|Republic of Ireland]] (2007 data). Globally, wind power generation more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2006.<ref> [http://www.wwindea.org/ WWEA]</ref> |

'''Wind power''' is the conversion of wind energy into useful form, such as electricity, using [[wind turbine]]s. In [[windmill]]s, wind energy is directly used to crush grain or to pump water. At the end of 2006, worldwide capacity of wind-powered generators was 73.9 [[gigawatt]]s.<ref name="wwindea"> [http://www.wwindea.org/home/images/stories/pdfs/pr_statistics2006_290107.pdf World Wind Energy Association Statistics] (PDF).</ref> Although wind currently produces just over 1% of world-wide electricity use, it accounts for approximately 19% of electricity production in [[Wind power in Denmark|Denmark]], 9% in [[Wind power in Spain|Spain]] and [[Wind power in Portugal|Portugal]], and 6% in [[Wind power in Germany|Germany]] and the [[Wind power in Ireland|Republic of Ireland]] (2007 data). Globally, wind power generation more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2006.<ref> [http://www.wwindea.org/ WWEA]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:46, 4 February 2008

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Megan jones I would like to to apoligize for staring at your tits sorry

Wind power is the conversion of wind energy into useful form, such as electricity, using wind turbines. In windmills, wind energy is directly used to crush grain or to pump water. At the end of 2006, worldwide capacity of wind-powered generators was 73.9 gigawatts.[1] Although wind currently produces just over 1% of world-wide electricity use, it accounts for approximately 19% of electricity production in Denmark, 9% in Spain and Portugal, and 6% in Germany and the Republic of Ireland (2007 data). Globally, wind power generation more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2006.[2]

Wind power is produced in large scale wind farms connected to electrical grids, as well as in individual turbines for providing electricity to isolated locations.

Wind energy is plentiful, renewable, widely distributed, clean, and reduces greenhouse gas emissions when it displaces fossil-fuel-derived electricity. The intermittency of wind seldom creates insurmountable problems when using wind power to supply up to roughly 10% of total electrical demand (low to moderate penetration), but it presents challenges that are not yet fully solved when wind is to be used for a larger fraction of demand.[3]

History

The earliest windmill was used to power an organ in the 1st century AD.[4] Windmills were used extensively in Northwestern Europe to grind flour beginning in the 1180s, and many Dutch windmills still exist.[5]

In the United States, the development of the "water-pumping windmill" was the major factor in allowing the farming and ranching of vast areas of North America, which were otherwise devoid of readily accessible water. They contributed to the expansion of rail transport systems throughout the world, by pumping water from wells to supply the needs of the steam locomotives of those early times.[6]

The multi-bladed wind turbine atop a lattice tower made of wood or steel was, for many years, a fixture of the landscape throughout rural America.

The modern wind turbine was developed beginning in the 1980s, although designs are still under development.

Wind energy

The origin of wind is complex. The Earth is unevenly heated by the sun resulting in the poles receiving less energy from the sun than the equator does. Also the dry land heats up (and cools down) more quickly than the seas do. The differential heating drives a global atmospheric convection system reaching from the Earth's surface to the stratosphere which acts as a virtual ceiling. Most of the energy stored in these wind movements can be found at high altitudes where continuous wind speeds of over 160 km/h (100 mph) occur. Eventually, the wind energy is converted through friction into diffuse heat throughout the Earth's surface and the atmosphere.

There is an estimated 72 TW of wind energy on the Earth that potentially can be commercially viable.[7]

Potential turbine power

The amount of power transferred to a wind turbine is directly proportional to the density of the air, the area swept out by the rotor, and the cube of the wind speed.

The usable power available in the wind is given by:

- ,

where P = power in watts, α = an efficiency factor determined by the design of the turbine, ρ = mass density of air in kilograms per cubic meter, r = radius of the wind turbine in meters, and v = velocity of the air in meters per second.[8]

As the wind turbine extracts energy from the air flow, the air is slowed down, which causes it to spread out. Albert Betz, a German physicist, determined in 1919 (see Betz' law) that a wind turbine can extract at most 59% of the energy that would otherwise flow through the turbine's cross section, that is α can never be higher than 0.59 in the above equation. The Betz limit applies regardless of the design of the turbine.

This equation shows the effects of the mass rate of flow of air travelling through the turbine, and the energy of each unit mass of air flow due to its velocity. As an example, on a cool 15 °C (59 °F) day at sea level, air density is 1.225 kilograms per cubic metre. An 8 m/s (28.8 km/h or 18 mi/h) breeze blowing through a 100 meter diameter rotor would move almost 77,000 kilograms of air per second through the swept area. The total power of the example breeze through a 100 meter diameter rotor would be about 2.5 megawatts. Betz' law states that no more than 1.5 megawatts could be extracted.

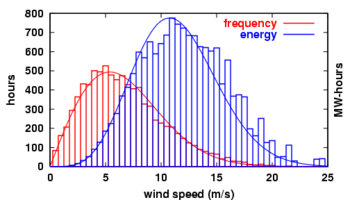

Distribution of wind speed

Windiness varies, and an average value for a given location does not alone indicate the amount of energy a wind turbine could produce there. To assess the frequency of wind speeds at a particular location, a probability distribution function is often fit to the observed data. Different locations will have different wind speed distributions. The Rayleigh model closely mirrors the actual distribution of hourly wind speeds at many locations.

Because so much power is generated by higher windspeed, much of the energy comes in short bursts. The 2002 Lee Ranch sample is telling; half of the energy available arrived in just 15% of the operating time. The consequence is that wind energy does not have as consistent an output as fuel-fired power plants; utilities that use wind power must provide backup generation for times that the wind is weak.

Grid management

Induction generators often used for wind power projects require reactive power for excitation, so substations used in wind-power collection systems include substantial capacitor banks for power factor correction. Different types of wind turbine generators behave differently during transmission grid disturbances, so extensive modelling of the dynamic electromechanical characteristics of a new wind farm is required by transmission system operators to ensure predictable stable behaviour during system faults. In particular, induction generators cannot support the system voltage during faults, unlike steam or hydro turbine-driven synchronous generators (however properly matched power factor correction capacitors along with electronic control of resonance can support induction generation without grid). Doubly-fed machines, or wind turbines with solid-state converters between the turbine generator and the collector system, have generally more desirable properties for grid interconnection. Transmission systems operators will supply a wind farm developer with a grid code to specify the requirements for interconnection to the transmission grid. This will include power factor, and dynamic behavior of the wind farm turbines during a system fault. [9] [10]

Capacity factor

Since wind speed is not constant, a wind farm's annual energy production is never as much as the sum of the generator nameplate ratings multiplied by the total hours in a year. The ratio of actual productivity in a year to this theoretical maximum is called the capacity factor. Typical capacity factors are 20-40%, with values at the upper end of the range in particularly favorable sites.[11][12] For example, a 1 megawatt turbine with a capacity factor of 35% will not produce 8760 megawatthours in a year, but only 0.35x24x365 = 3066 MWh. Online data is available for some locations and the capacity factor can be calculated from the yearly output.[13][14]

Unlike fueled generating plants, the capacity factor is limited by the inherent properties of wind. Capacity factors of other types of power plant are based mostly on fuel cost, with a small amount of downtime for maintenance. Nuclear plants have low incremental fuel cost, and so are run at full output and achieve a 90% capacity factor.[15] Plants with higher fuel cost are throttled back to follow load. Gas turbine plants using natural gas as fuel may be very expensive to operate and may be run only to meet peak power demand. A gas turbine plant may have an annual capacity factor of 5-25% due to relatively high energy production cost.

According to a 2007 Stanford University study published in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, interconnecting ten or more wind farms allows 33 to 47% of the total energy produced to be used as reliable, baseload electric power, as long as minimum criteria are met for wind speed and turbine height.[16]

Intermittency and penetration limits

Electricity generated from wind power can be highly variable at several different timescales: from hour to hour, daily, and seasonally. Annual variation also exists, but is not as significant. Because instantaneous electrical generation and consumption must remain in balance to maintain grid stability, this variability can present substantial challenges to incorporating large amounts of wind power into a grid system. Intermittency and the non-dispatchable nature of wind energy production can raise costs for regulation, incremental operating reserve, and (at high penetration levels) could require energy demand management, load shedding, or storage solutions. At low levels of wind penetration, fluctuations in load and allowance for failure of large generating units requires reserve capacity that can also regulate for variability of wind generation.

Pumped-storage hydroelectricity or other forms of grid energy storage can store energy developed by high-wind periods and release it when demanded. [17] Stored energy increases the economic value of wind energy since it can be shifted to displace higher cost generation during peak demand periods. The potential revenue from this arbitrage can offset the cost and losses of storage; the cost of storage may add 25% to the cost of wind energy.

Peak wind speeds may not coincide with peak demand for electrical power. In California and Texas, for example, hot days in summer may have low wind speed and high electrical demand due to air conditioning. In the UK, winter demand is high but so are wind speeds. [18] [19] [20] Wind, however, tends to be complementary to solar,[21][22] which peaks during the summer.[23] In addition, on most days with no wind there is sun and on most days with no sun there is wind. Live data from the Massachusetts Maritime Academy's wind turbine and solar panels is available for last week and last month to see this effect.

The 2006 Energy in Scotland Inquiry report expresses concern about some aspects of wind power.[24]

"The inherent intermittency of wind power means that it cannot be relied on to deliver firm output at any given time. However, its input when available has to be accepted into the grid. A diversity of supply is essential to achieve maximum security and flexibility in the supply of electricity."

A study commissioned by the state of Minnesota considered penetration of up to 25%, and concluded that integration issues would be manageable and have incremental costs of less than one-half cent ($0.0045) per kWh.[25] A similar report from Denmark noted that their wind power network was without power for 54 days during 2002.[26]

Penetration

Wind energy "penetration" refers to the fraction of energy produced by wind compared with the total available generation capacity. There is no generally accepted "maximum" level of wind penetration. The limit for a particular grid will depend on the existing generating plants, pricing mechanisms, capacity for storage or demand management, and other factors. Studies have indicated that 20% of the total electrical energy consumption may be incorporated with minimal difficulty.[27] These studies have been for locations with geographically dispersed wind farms, some degree of dispatchable energy, or hydropower with storage capacity, demand management, and interconnection to a large grid area export of electricity when needed. Beyond this level, there are few technical limits, but the economic implications become more significant.

At present, few grid systems have penetration of wind energy above 5%: Denmark (values over 18%), Spain and Portugal (values over 9%), Germany and the Republic of Ireland (values over 6%). The Danish grid is heavily interconnected to the European electrical grid, and it has solved grid management problems by exporting almost half of its wind power to Norway. The correlation between electricity export and wind power production is very strong.[28]

Predictability

Related to variability is the short-term (hourly or daily) predictability of wind plant output. Like other electricity sources, wind energy must be "scheduled". The nature of this energy source makes it inherently variable. Wind power forecasting methods are used, but predictability of wind plant output remains low for short-term operation.

Turbine placement

Proper selection of a wind power site and positioning of turbines within the site is critical to economic development of wind power. Aside from the availability of wind itself, other significant factors include the availability of transmission lines, cost of land acquisition, land use considerations, and environmental impact of construction and operations. Off-shore locations may offset their higher construction cost with higher annual load factors, thereby reducing cost of energy produced.

Utilization of wind power

| Installed windpower capacity (MW)[29][30] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Nation | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

| 1 | Germany | 18,415 | 20,622 | 22,247 |

| 2 | United States | 9,149 | 11,603 | 16,818 |

| 3 | Spain | 10,028 | 11,615 | 15,145 |

| 4 | India | 4,430 | 6,270 | ~ 8,000 |

| 5 | China | 1,260 | 2,604 | 6,050 |

| 6 | Denmark (& Faeroe Islands) | 3,136 | 3,140 | |

| 7 | Italy | 1,718 | 2,123 | 2,726 |

| 8 | United Kingdom | 1,332 | 1,963 | 2,388 |

| 9 | Portugal | 1,022 | 1,716 | 2,065 |

| 10 | Canada | 683 | 1,459 | 1,770 |

| 11 | France | 757 | 1,567 | 2,100 |

| 12 | Netherlands | 1,219 | 1,560 | |

| 13 | Japan | 1,061 | 1,394 | |

| 14 | Austria | 819 | 965 | |

| 15 | Australia | 708 | 817 | |

| 16 | Greece | 573 | 746 | 871 |

| 17 | Ireland | 496 | 745 | 866 |

| 18 | Sweden | 510 | 572 | |

| 19 | Norway | 267 | 314 | |

| 20 | Brazil | 29 | 237 | |

| 21 | Egypt | 145 | 230 | 580 |

| 22 | Belgium | 167 | 193 | |

| 23 | Taiwan | 104 | 188 | |

| 24 | South Korea | 98 | 173 | |

| 25 | New Zealand | 169 | 171 | 322 |

| 26 | Poland | 83 | 153 | 280 |

| 27 | Morocco | 64 | 124 | |

| 28 | Mexico | 3 | 88 | |

| 29 | Finland | 82 | 86 | 110 |

| 30 | Ukraine | 77 | 86 | |

| 31 | Costa Rica | 71 | 74 | |

| 32 | Hungary | 18 | 61 | |

| 33 | Lithuania | 6 | 55 | |

| 34 | Turkey | 20 | 51 | |

| 35 | Czech Republic | 28 | 50 | |

| 36 | Iran | 23 | 48 | |

| Rest of Europe | 129 | 163 | ||

| Rest of Americas | 109 | 109 | ||

| Rest of Asia | 38 | 38 | ||

| Rest of Africa & Middle East | 31 | 31 | ||

| Rest of Oceania | 12 | 12 | ||

| World total (MW) | 59,091 | 74,223 | ~ 94,000 | |

There are many thousands of wind turbines operating, with a total capacity of 73,904 MW of which wind power in Europe accounts for 65% (2006). Wind power was the most rapidly growing means of alternative electricity generation at the turn of the 21st century. World wind generation capacity more than quadrupled between 2000 and 2006. 81% of wind power installations are in the US and Europe, but the share of the top five countries in terms of new installations fell from 71% in 2004 to 62% in 2006.

By 2010, the World Wind Energy Association expects 160GW of capacity to be installed worldwide,[1] up from 73.9GW at the end of 2006, implying an anticipated net growth rate of more than 21% per year.

Germany, Spain, the United States, India, and Denmark have made the largest investments in wind-generated electricity. Denmark is prominent in the manufacturing and use of wind turbines, with a commitment made in the 1970s to eventually produce half of the country's power by wind. Denmark generates over 20% of its electricity with wind turbines -- the highest percentage of any country -- and is fifth in the world in total wind power generation (but Denmark is 56th on the List of countries by electricity consumption).

Germany is the leading producer of wind power, with 28% of the total world capacity in 2006 and a total output of 38.5 TWh in 2007 (6.3% of German electricity); the official target is for renewable energy to meet 12.5% of German electricity needs by 2010 — this target may be reached ahead of schedule. Germany has 18,600 wind turbines, mostly in the north of the country — including three of the biggest in the world, constructed by the companies Enercon (6 MW), Multibrid (5 MW) and Repower (5 MW). Germany's Schleswig-Holstein province generates 36% of its power with wind turbines.

In 2005, the government of Spain approved a new national goal for installed wind power capacity of 20,000 MW in 2010. With a record installation of 3515 MW in 2007 (for a total figure of 15,145 MW), this target will probably be reached ahead of schedule. A significant acceleration of the bureaucratic proceedings and connections to grid, and the legislative change occurred during 2007 (with Royal Decree 661/2007), have accelerated the developing of many wind parks, so that they could still run under the previous more favourable conditions.

In recent years, the United States has added more wind energy to its grid than any other country; U.S. wind power capacity grew by 45% to 16.8 gigawatts in 2007.[31] Texas has become the largest wind energy producing state, surpassing California. In 2007, the state expects to add 2 gigawatts to its existing capacity of approximately 4.5 gigawatts. Iowa and Minnesota are expected to each produce 1 gigawatt by late-2007.[32] Wind power generation in the U.S. was up 31.8% in February, 2007 from February, 2006.[33] The average output of one megawatt of wind power is equivalent to the average electricity consumption of about 250 American households. According to the American Wind Energy Association, wind generated enough electricity to power 0.4% (1.6 million households) of total electricity in US, up from less than 0.1% in 1999. US Department of Energy studies have concluded wind harvested in just three of the fifty U.S. states could provide enough electricity to power the entire nation, and that offshore wind farms could do the same job.[34]

India ranks 4th in the world with a total wind power capacity of 6,270 MW in 2006, or 3% of all electricity produced in India. The World Wind Energy Conference in New Delhi in November 2006 has given additional impetus to the Indian wind industry.[1] The windfarm near Muppandal, Tamil Nadu, India, provides an impoverished village with energy.[35][36] India-based Suzlon Energy is one of the world's largest wind turbine manufacturers.[37]

In December 2003, General Electric installed the world's largest offshore wind turbines in Ireland, and plans are being made for more such installations on the west coast, including the possible use of floating turbines.

In 2005, China announced it would build a 1000-megawatt wind farm in Hebei for completion in 2020. China reportedly has set a generating target of 20,000 MW by 2020 from renewable energy sources — it says indigenous wind power could generate up to 253,000 MW. Following the World Wind Energy Conference in November 2004, organised by the Chinese and the World Wind Energy Association, a Chinese renewable energy law was adopted. In late 2005, the Chinese government increased the official wind energy target for the year 2020 from 20 GW to 30 GW.[38]

Mexico recently opened La Venta II wind power project as an important step in reducing Mexico's consumption of fossil fuels. The project (88MW) the first of its kind in Mexico, will provide 13 percent of the electricity needs of the state of Oaxaca and by 2012 will have a capacity of 3500 MW.

Another growing market is Brazil, with a wind potential of 143 GW.[39] The federal government has created an incentive program, called Proinfa,[40] to build production capacity of 3300 MW of renewable energy for 2008, of which 1422 MW through wind energy. The program seeks to produce 10% of Brazilian electricity through renewable sources.

France recently announced a very ambitious target of 12 500 MW installed by 2010.

Canada experienced rapid growth of wind capacity between 2000 and 2006, with total installed capacity increasing from 137 MW to 1,451 MW, and showing an annual growth rate of 38%.[41] Particularly rapid growth has been seen in 2006, with total capacity doubling from the 684 MW at end-2005.[42] This growth was fed by measures including installation targets, economic incentives and political support. For example, the Ontario government announced that it will introduce a feed-in tariff for wind power, referred to as 'Standard Offer Contracts', which may boost the wind industry across the province.[43] In Quebec, the provincially-owned electric utility plans to purchase an additional 2000 MW by 2013.[44]

Small scale wind power

Small wind generation systems with capacities of 100 kW or less are usually used to power homes, farms, and small businesses. Isolated communities that otherwise rely on diesel generators may use wind turbines to displace diesel fuel consumption. Individuals purchase these systems to reduce or eliminate their electricity bills, or simply to generate their own clean power.

Wind turbines have been used for household electricity generation in conjunction with battery storage over many decades in remote areas. Increasingly, U.S. consumers are choosing to purchase grid-connected turbines in the 1 to 10 kilowatt range to power their whole homes. Household generator units of more than 1 kW are now functioning in several countries, and in every state in the U.S.

Grid-connected wind turbines may use grid energy storage, displacing purchased energy with local production when available. Off-grid system users either adapt to intermittent power or use batteries, photovoltaic or diesel systems to supplement the wind turbine.

In urban locations, where it is difficult to obtain predictable or large amounts of wind energy, smaller systems may still be used to run low power equipment. Equipment such as parking meters or wireless internet gateways may be powered by a wind turbine that charges a small battery, replacing the need for a connection to the power grid.

Economics and feasibility

Growth and cost trends

Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) figures show that 2006 recorded an increase of installed capacity of 15,197 megawatts (MW), taking the total installed wind energy capacity to 74,223 MW, up from 59,091 MW in 2005. Despite constraints facing supply chains for wind turbines, the annual market for wind continued to increase at an estimated rate of 32% following the 2005 record year, in which the market grew by 41%. In terms of economic value, the wind energy sector has become one of the important players in the energy markets, with the total value of new generating equipment installed in 2006 reaching €18 billion, or US$23 billion.[29]

In 2004, wind energy cost one-fifth of what it did in the 1980s, and some expected that downward trend to continue as larger multi-megawatt turbines are mass-produced.[45] However, installation costs have increased significantly in 2005 and 2006, and according to the major U.S. wind industry trade group, now average over US$1,600 per kilowatt,[46] compared to $1200/kW just a few years before. Not as many facilities can produce large modern turbines and their towers and foundations, so constraints develop in the supply of turbines resulting in higher costs.

Wind and hydro power have negligable fuel costs and relatively low maintenance costs; in economic terms, wind power has a low marginal cost and a high proportion of capital cost. The estimated average cost per unit incorporates the cost of construction of the turbine and transmission facilities, borrowed funds, return to investors (including cost of risk), estimated annual production, and other components, averaged over the projected useful life of the equipment, which may be in excess of twenty years. Energy cost estimates are highly dependent on these assumptions so published cost figures can differ substantially. A British Wind Energy Association report gives an average generation cost of onshore wind power of around 3.2 pence per kilowatt hour (2005).[47] Cost per unit of energy produced was estimated in 2006 to be comparable to the cost of new generating capacity in the United States for coal and natural gas: wind cost was estimated at $55.80 per MWh, coal at $53.10/MWh and natural gas at $52.50.[48] Other sources in various studies have estimated wind to be more expensive than other sources (see Economics of new nuclear power plants, Clean coal, and Carbon capture and storage).

Similar methods apply to other electrical energy sources. Existing generation capacity represents sunk costs, and the decision to continue production will depend on marginal costs going forward, not estimated average costs at project inception. For example, the estimated cost of new wind power capacity may be lower than that for "new coal" (estimated average costs for new generation capacity) but higher than for "old coal" (marginal cost of production for existing capacity). Therefore, the choice to increase wind capacity will depend on factors including the profile of existing generation capacity.

Research from a wide variety of sources in various countries shows that support for wind power is consistently between 70 and 80 per cent amongst the general public.[49]

Theoretical potential

Wind power available in the atmosphere is much greater than current world energy consumption. The most comprehensive study to date[50] found the potential of wind power on land and near-shore to be 72 TW, equivalent to 54,000 MToE (million tons of oil equivalent) per year, or over five times the world's current energy use in all forms. The potential takes into account only locations with mean annual wind speeds ≥ 6.9 m/s at 80 m. It assumes 6 turbines per square km for 77 m diameter, 1.5 MW-turbines on roughly 13% of the total global land area (though that land would also be available for other compatible uses such as farming). The authors acknowledge that many practical barriers would need to be overcome to reach this theoretical capacity.

The practical limit to exploitation of wind power will be set by economic and environmental factors, since the resource available is far larger than any practical means to develop it.

Direct costs

Many potential sites for wind farms are far from demand centers, requiring substantially more money to construct new transmission lines and substations.

Since the primary cost of producing wind energy is construction and there are no fuel costs, the average cost of wind energy per unit of production is dependent on a few key assumptions, such as the cost of capital and years of assumed service. The marginal cost of wind energy once a plant is constructed is usually less than 1 cent per kilowatt-hour.[51] Since the cost of capital plays a large part in projected cost, risk (as perceived by investors) will affect projected costs per unit of electricity.

The commercial viability of wind power also depends on the pricing regime for power producers. Electricity prices are highly regulated worldwide, and in many locations may not reflect the full cost of production, let alone indirect subsidies or negative externalities. Customers may enter into long-term pricing contracts for wind to reduce the risk of future pricing changes, thereby ensuring more stable returns for projects at the development stage. These may take the form of standard offer contracts, whereby the system operator undertakes to purchase power from wind at a fixed price for a certain period (perhaps up to a limit); these prices may be different than purchase prices from other sources, and even incorporate an implicit subsidy.

In jurisdictions where the price for electricity is based on market mechanisms, revenue for all producers per unit is higher when their production coincides with periods of higher prices. The profitability of wind farms will therefore be higher if their production schedule coincides with these periods. If wind represents a significant portion of supply, average revenue per unit of production may be lower as more expensive and less-efficient forms of generation, which typically set revenue levels, are displaced from economic dispatch.[citation needed] This may be of particular concern if the output of many wind plants in a market have strong temporal correlation. In economic terms, the marginal revenue of the wind sector as penetration increases may diminish.

External costs

Most forms of energy production create some form of negative externality: costs that are not paid by the producer or consumer of the good. For electric production, the most significant externality is pollution, which imposes social costs in increased health expenses, reduced agricultural productivity, and other problems. In addition, carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas produced when fossil fuels are burned, may impose even greater costs in the form of global warming. Few mechanisms currently exist to internalise these costs, and the total cost is highly uncertain. Other significant externalities can include military expenditures to ensure access to fossil fuels, remediation of polluted sites, destruction of wild habitat, loss of scenery/tourism, etc.

If the external costs are taken into account, wind energy may be competitive in more cases. Wind energy costs have generally decreased due to technology development and scale enlargement. Wind energy supporters argue that, once external costs and subsidies to other forms of electrical production are accounted for, wind energy is amongst the least costly forms of electrical production. Critics argue that the level of required subsidies, the small amount of energy needs met, and the uncertain financial returns to wind projects make it inferior to other energy sources. Intermittency and other characteristics of wind energy also have costs that may rise with higher levels of penetration, and may change the cost-benefit ratio.

Incentives

Wind energy in many jurisdictions receives some financial or other support to encourage its development. A key issue is the comparison to other forms of energy production, and their total cost. Two main points of discussion arise: direct subsidies and externalities for various sources of electricity, including wind. Wind energy benefits from subsidies of various kinds in many jurisdictions, either to increase its attractiveness, or to compensate for subsidies received by other forms of production or which have significant negative externalities.

In the United States, wind power receives a tax credit for each kilowatt-hour produced; at 1.9 cents per kilowatt-hour in 2006, the credit has a yearly inflationary adjustment. Another tax benefit is accelerated depreciation. Many American states also provide incentives, such as exemption from property tax, mandated purchases, and additional markets for "green credits." Countries such as Canada and Germany also provide incentives for wind turbine construction, such as tax credits or minimum purchase prices for wind generation, with assured grid access (sometimes referred to as feed-in tariffs). These feed-in tariffs are typically set well above average electricity prices.

Environmental effects

CO2 emissions and pollution

Wind power consumes no fuel for continuing operation, and has no emissions directly related to electricity production. Operation does not produce carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, mercury, particulates, or any other type of air pollution, as do fossil fuel power sources. Wind power plants consume resources in manufacturing and construction. During manufacture of the wind turbine, steel, concrete, aluminum and other materials will have to be made and transported using energy-intensive processes, generally using fossil energy sources. The initial carbon dioxide emissions "pay back" within about 9 months of operation for off shore turbines.[53]

Wind power may affect emissions at fossil-fuel plants used for reserve and regulation:

It is sometimes said that wind energy, for example, does not reduce carbon dioxide emissions because the

intermittent nature of its output means it needs to be backed up by fossil fuel plants. Wind turbines do not displace fossil generating capacity on a one-for-one basis. But it is unambiguously the case that wind

energy can displace fossil fuel-based generation, reducing both fuel use and carbon dioxide emissions.[54]

A study by the Irish national grid stated that "Producing electricity from wind reduces the consumption of fossil fuels and therefore leads to emissions savings", and found reductions in CO2 emissions ranging from 0.33 to 0.59 tonnes of CO2 per MWh.[55]

Net energy gain

The energy return on investment (EROI) for wind energy is equal to the cumulative electricity generated divided by the cumulative primary energy required to build and maintain a turbine. The EROI for wind ranges from 5 to 35, with an average of around 18. EROI is strongly proportional to turbine size [56], and larger late-generation turbines are at the high end of this range, at or above 35. [57] This places wind energy in a favorable position relative to conventional power generation technologies in terms of EROI. Since energy produced is several times energy consumed in construction, there is a net energy gain. The energy used for construction is produced by the wind turbine within a few months of operation.

Ecological footprint

Unlike fossil fuel and nuclear power stations, which circulate or evaporate large amounts of water for cooling, wind turbines do not need water to generate electricity.

Several incidents have been reported of oil or hydraulic fluid being leaked into the surrounding environment, in some cases contaminating protected drinking water areas. The liquid can run down the blades during motion and be dispersed over a wide area.[58]

Land use

Wind turbines should ideally be placed about ten times their diameter apart in the direction of prevailing winds and five times their diameter apart in the perpendicular direction for minimal losses due to wind park effects. As a result, wind turbines require roughly 0.1 square kilometres of unobstructed land per megawatt of nameplate capacity. A 200 MW wind farm, which might produce as much energy each year as a 100 MW baseload power plant, might have turbines spread out over an area of approximately 20 square kilometres.

Clearing of wooded areas is often unnecessary. Farmers commonly lease land to companies building wind farms. In the U.S., farmers may receive annual lease payments of two thousand to five thousand dollars per turbine.[59] The land can still be used for farming and cattle grazing. Less than 1% of the land would be used for foundations and access roads, the other 99% could still be used for farming.[60] Turbines can be sited on unused land in techniques such as center pivot irrigation. The clearing of trees around tower bases may be necessary for installation sites on mountain ridges, such as in the northeastern U.S.[61]

Turbines are not generally installed in urban areas. Buildings may interfere with wind, and the value of land is high. Despite these issues, Toronto's demonstration project demonstrates that such installations are possible.

Offshore locations, such as that being developed on a large underwater plateau in eastern Lake Ontario by Trillium Power use no land per se and avoid known shipping channels. Some offshore locations are uniquely located close to ample transmission and high load centres however that is not the norm for most offshore locations. Most offshore locations are at considerable distances from load centres and may face transmission and line loss challenges.

Wind turbines located in agricultural areas may create concerns by operators of cropdusting aircraft. Operating rules may prohibit approach of aircraft within a stated distance of the turbine towers; turbine operators may agree to curtail operations of turbines during cropdusting operations.

Impact on wildlife

Birds

Some wind turbines kill birds, especially birds of prey.[62] More recent siting generally takes into account known bird flight patterns. Studies show that the number of birds killed by wind turbines is negligible compared to the number that die as a result of other human activities such as traffic, hunting, power lines and high-rise buildings and especially the environmental impacts of using non-clean power sources. For example, in the UK, where there are several hundred turbines, about one bird is killed per turbine per year; 10 million per year are killed by cars alone.[63] In the United States, turbines kill 70,000 birds per year, compared to 57 million killed by cars and 97.5 million killed by collisions with plate glass.[64] An article in Nature stated that each wind turbine kills on average 0.03 birds per year, or one kill per thirty turbines.[65]

In the UK, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) concluded that "The available evidence suggests that appropriately positioned wind farms do not pose a significant hazard for birds."[66] It notes that climate change poses a much more significant threat to wildlife, and therefore supports wind farms and other forms of renewable energy.

Some paths of bird migration, particularly for birds that fly by night, are unknown. Another study suggests that migrating birds adapt to obstacles; those birds which continue to fly through a wind farm avoid the large turbines,[67] at least in the low-wind non-twilight conditions studied. A Danish 2005 (Biology Letters 2005:336) study showed that radio tagged migrating birds traveled around offshore wind farms, with less than 1% of migrating birds passing an offshore wind farm in Rønde, Denmark, got close to collision, though the site was studied only during low-wind non-twilight conditions.

A survey at Altamont Pass, California, conducted by a California Energy Commission in 2004 showed that onshore turbines killed between 1,766 and 4,721[68] birds annually (881 to 1,300 of which were birds of prey). Radar studies of proposed onshore and near-shore sites in the eastern U.S. have shown that migrating songbirds fly well within the reach of large modern turbine blades. In Australia, a proposed wind farm was canceled because of the possibility that a single endangered bird of prey was nesting in the area.[citation needed]

A wind farm in Norway's Smøla islands is reported to have affected a colony of sea eagles, according to the British Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Turbine blades killed ten of the birds between August 2005 and March 2007, including three of the five chicks that fledged in 2005. Nine of the 16 nesting territories appear to have been abandoned. Norway is regarded as the most important place for white-tailed eagles.[69][70]

Bats

The numbers of bats killed by existing onshore and near-shore facilities has troubled bat enthusiasts.[71] A study in 2004 estimated that over 2200 bats were killed by 63 onshore turbines in just six weeks at two sites in the eastern U.S.[72] This study suggests some onshore and near-shore sites may be particularly hazardous to local bat populations and more research is urgently needed. Migratory bat species appear to be particularly at risk, especially during key movement periods (spring and more importantly in fall). Lasiurines such as the hoary bat, red bat, and the silver-haired bat appear to be most vulnerable at North American sites. Almost nothing is known about current populations of these species and the impact on bat numbers as a result of mortality at windpower locations. Offshore wind sites 10 km or more from shore do not interact with bat populations.

Fish

In Ireland, construction of a wind farm caused pollution feared to be responsible for wiping out vegetation and fish stocks in the Lough Lee.[73] A separate landslide is thought to have been caused by wind farm construction, and has killed thousands of fish by polluting the local rivers with sediment.[74]

Offshore ocean noise

As the number of offshore wind farms increase and move further into deeper water, the question arises if the ocean noise that is generated due to mechanical motion of the turbines and other vibrations which can be transmitted via the tower structure to the sea, will become significant enough to harm sea mammals. Tests carried out in Denmark for shallow installations showed the levels were only significant up to a few hundred metres. However, sound injected into deeper water will travel much further and will be more likely to impact bigger creatures like whales which tend to use lower frequencies than porpoises and seals. A recent study found that wind farms add 80–110 dB to the existing low-frequency ambient noise (under 400 Hz), which could impact baleen whales communication and stress levels, and possibly prey distribution.[75]

Safety

Operation of any utility-scale energy conversion system presents safety hazards. Wind turbines do not consume fuel or produce pollution during normal operation, but still have hazards associated with their construction and operation.

There have been at least 40 fatalities due to construction, operation, and maintenance of wind turbines, including both workers and members of the public, and other injuries and deaths attributed to the wind power life cycle.[76][77][78] Most worker deaths involve falls or becoming caught in machinery while performing maintenance inside turbine housings. Blade failures and falling ice have also accounted for a number of deaths and injuries. Deaths to members of the public include a parachutist colliding with a turbine and small aircraft crashing into support structures. Other public fatalities have been blamed on collisions with transport vehicles and motorists distracted by the sight and shadow flicker of wind turbines along highways.[79]

When a turbine's brake fails, the turbine can spin freely until it disintegrates or catches fire. This is mitigated in most modern designs by wing-trip aero breaks, variable pitch blades, and the ability to turn the nacelle to face out of the wind. Turbine blades may fail spontaneously due to manufacturing flaws. Lightning strikes are a common problem, also causing rotor blade damage and fires.[78][80][81][82] When ejected, pieces of broken blade and ice can be thrown hundreds of meters away. Although no member of the public has been killed by a malfunctioning turbine, there have been close calls, including injury by falling ice. Large pieces of debris, up to several tons, have dropped in populated areas, residential properties, and roads, damaging cars and homes.[78]

Often turbine fires cannot be extinguished because of the height, and are left to burn themselves out. In the process, they generate toxic fumes and can scatter flaming debris over a wide area, starting secondary fires below. Several turbine-ignited fires have burned hundreds of acres of vegetation each, and one burned 80,000 hectares (200,000 acres) of Australian National Park.[78][83][84][85]

Electronic controllers and safety sub-systems monitor many different aspects of the turbine, generator, tower, and environment to determine if the turbine is operating in a safe manner within prescribed limits. These systems can temporarily shut down the turbine due to high wind, electrical load imbalance, vibration, and other problems. Reoccurring or significant problems cause a system lockout and notify an engineer for inspection and repair. In addition, most systems include multiple passive safety systems that stop operation even if the electronic controller fails.

Wind power proponent and author Paul Gipe estimated in Wind Energy Comes of Age that the mortality rate for wind power from 1980–1994 was 0.4 deaths per terawatt-hour.[86][87] Paul Gipe's estimate as of end 2000 was 0.15 deaths per TWh, a decline attributed to greater total cumulative generation.

By comparison, hydroelectric power was found to to have a fatality rate of 0.10 per TWh (883 fatalities for every TW·yr) in the period 1969–1996.[88] This includes the Banqiao Dam collapse in 1975 that killed thousands. Although the wind power death rate is higher than some other power sources, the numbers are necessarily based on a small sample size. The apparent trend is a reduction in fatalities per TWh generated as more generation is supplied by larger units.

Aesthetics

Historical experience of noisy and visually intrusive wind turbines may create resistance to the establishment of land-based wind farms. Residents near turbines may complain of "shadow flicker" caused by rotating turbine blades. Wind towers require aircraft warning lights, which create bothersome light pollution. Complaints about these lights have caused the FAA to consider allowing fewer lights per turbine in certain areas.[89]

These effects may be countered by changes in wind farm design.

Modern large turbines have low sound levels at ground level. For example, in December 2006, a Texas jury denied a noise pollution suit against FPL Energy, after the company demonstrated that noise readings were not excessive. The highest reading was 44 decibels, which was characterized as about the same level as a 10 mile/hour (16 km/hr) wind.[90]

Newer wind farms have larger, more widely spaced turbines, and so look less cluttered than old installations.

Aesthetic issues are important for onshore and near-shore locations in that the "visible footprint" may be extremely large compared to other sources of industrial power (which may be sited in industrially developed areas). Wind farms may be close to scenic or otherwise undeveloped areas. Offshore wind development locations remove the visual aesthetic issue by being at least 10 km from shore and in many cases much further away.

Examples of opposition to wind power

- After a wind farm was proposed several miles off the coast of Cape Cod, environmentalists raised objections. Ted Kennedy, typically a supporter of wind power, owns a summer home in the area and objected to the proposal.[91]

- On October 16, 2003 in Galway, Ireland, construction of the foundation of a wind farm caused almost half a square kilometer of bog to slide 2.5 kilometers down a hillside. The slide destroyed an unoccupied farmhouse and blocked two roads. Nearby residents expressed concern over these environmental impacts.[92]

- On December 4, 2007, environmentalists filed lawsuits to block two proposed wind farms in southern Texas. The lawsuits expressed concerns over wetlands, habitat, endangered species and migratory birds.[93]

- On January 12, 2004, it was reported that the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit against wind farm owners for killing tens of thousands of birds at the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area near San Francisco, California.[94]

- On December 7, 2007, it was reported that environmentalists opposed a plan to build a wind farm in western Maryland. Ajax Eastman, whom the article described as "a conservationist from Baltimore whose opposition has helped stall construction of other wind farms in western Maryland," was quoted as saying, "The idea of destroying the Appalachian ridge tops for such a little bit of energy capacity doesn't make any sense to me." Paulette Hammond, president of the Maryland Conservation Council, was quoted as saying, "This would denude some very valuable forest tree canopy ... and wouldn't provide nearly the amount of energy we'll need." The article also said, "Dan Boone, a former state wildlife biologist who has been fighting wind farms in western Maryland, said that the Savage River and Potomac state forests contain rare old-growth trees and that threatened species that shouldn't be disturbed."[95]

See also

- Energy development

- List of wind turbine manufacturers

- Wind-Diesel

- The Windbelt, a non-turbine approach to tapping wind power

- World energy resources and consumption

- Distributed Energy Resources

- Merchant Wind Power

- Green energy

- Green tax shift

- Grid energy storage

- Renewable energy

- Category:Wind power by country

- List of large wind farms

- SkySails

References

- ^ a b c World Wind Energy Association Statistics (PDF).

- ^ WWEA

- ^ Hannele Holttinen; et al. (September 2006). ""Design and Operation of Power Systems with Large Amounts of Wind Power", IEA Wind Summary Paper" (PDF). Global Wind Power Conference September 18-21, 2006, Adelaide, Australia.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ A.G. Drachmann, "Heron's Windmill", Centaurus, 7 (1961), pp. 145-151

- ^ Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp.1-30 (18ff.)

- ^ Quirky old-style contraptions make water from wind on the mesas of West Texas

- ^ Mapping the global wind power resource.

- ^ Iowa Energy Center Wind Energy Manual.

- ^ Robert Zavadil et al, Making Connections: Wind Generation Challenges and Progress, IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, Nov/Dec. 2005, pgs. 27-37

- ^ Edgar A. DeMoe et al, Wind Plant Integration: Cost, Status and Issues, 'IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, Nov/Dec. 2005, pgs. 39-46

- ^ How Does A Wind Turbine's Energy Production Differ from Its Power Production?

- ^ Wind Power: Capacity Factor, Intermittency, and what happens when the wind doesn’t blow? retrieved 24 January 2008

- ^ Massachusetts Maritime Academy — Bourne, Mass This 660 kW wind turbine has a capacity factor of about 19%.

- ^ Wind Power in Ontario These wind farms have capacity factors of about 28 to 35%.

- ^ Nuclear Energy Institute. "Nuclear Facts". Retrieved 2006-07-23.

- ^ "The power of multiples: Connecting wind farms can make a more reliable and cheaper power source". 2007-11-21.

- ^ Mitchell 2006.

- ^ David Dixon, Nuclear Engineer (2006-08-09). "Wind Generation's Performance during the July 2006 California Heat Storm". US DOE, Oakland Operations.

- ^ The Environmental Effects of Electricity Generation

- ^ Graham Sinden (2005-12-01). "Characteristics of the UK wind resource: Long-term patterns and relationship to electricity demand". Environmental Change Institute, Oxford University Centre for the Environment.

- ^ Wind + sun join forces at Washington power plant Retrieved 31 January 2008

- ^ Fundamental Study on Complementary Effect between Wind and Solar Energy based on Meteorological Data

- ^ Small Wind Systems

- ^ ""Inquiry into Energy Issues for Scotland"; Summary Report" (PDF). Royal Society of Edinburgh. June 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ ""Final Report - 2006 Minnesota Wind Integration Study"" (PDF). The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission. November 30, 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Why wind power works for Denmark" (PDF). Civil Engineering. May 2005. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ +format= PDF (January 2007). "Tackling Climate Change in the U.S." (PDF). American Solar Energy Society. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ ""Analysis of Wind Power in the Danish Electricity Supply in 2005 and 2006" (translated from Danish)" (PDF). 10-08-2007. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) statistics" (PDF). Cite error: The named reference "GWEC" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "European Wind Energy Association (EWEA) statistics" (PDF).

- ^ "Installed U.S. Wind Power Capacity Surged 45% in 2007". American Wind Power Association. January 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://awea.org/projects

- ^ "Electric Power Monthly (January 2008 Edition)". Energy Information Administration. January 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Massachusetts — 50 m Wind Power" (JPEG). U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. 06 Feb 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Tapping the Wind — India". 2005. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Watts, Himangshu (2003). "Clean Energy Brings Windfall to Indian Village". Reuters News Service. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Suzlon Energy

- ^ Lema, Adrian and Kristian Ruby, ”Between fragmented authoritarianism and policy coordination: Creating a Chinese market for wind energy”, Energy Policy, Vol. 35, Isue 7, July 2007.

- ^ "Atlas do Potencial Eólico Brasileiro". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Eletrobrás — Centrais Elétricas Brasileiras S. A — Projeto Proinfa". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Wind Energy: Rapid Growth" (PDF). Canadian Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Canada's Current Installed Capacity" (PDF). Canadian Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ "Standard Offer Contracts Arrive In Ontario". Ontario Sustainable Energy Association. 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Call for Tenders A/O 2005-03: Wind Power 2,000 MW". Hydro-Québec. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ Helming, Troy (February 2 2004). "Uncle Sam's New Year's Resolution". RE Insider. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Wind Power Increased by 27% in 2006". American Wind Energy Association. January 23 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ BWEA report on onshore wind costs (PDF).

- ^ ""International Energy Outlook", 2006" (PDF). Energy Information Administration. p. 66.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Fact sheet 4: Tourism

- ^ Archer, Cristina L. "Evaluation of global wind power". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Wind and Solar Power Systems — Design, analysis and Operation" (2nd ed., 2006), Mukund R. Patel, p. 303

- ^ Wind Plants of California's Altamont Pass

- ^ "Vestas: Life Cycle Assessments (LCA)". Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Costs and Impacts of Intermittency, UK Energy Research Council, March 2006

- ^ ""Impact of Wind Generation in Ireland on the Operation of Conventional Plant and the Economic Implications"" (PDF). ESB National Grid. February 2004. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/10/17/18478/085 Figure 2]

- ^ [1]

- ^ Craig, David (2007-11-30). "Summary of Wind Turbine Accident data". Caithness Windfarm Information Forum. Retrieved 2007-12-30. - Table of accidents, PDF format

- ^ "RENEWABLE ENERGY — Wind Power's Contribution to Electric Power Generation and Impact on Farms and Rural Communities (GAO-04-756)" (PDF). United States Government Accountability Office. September 2004. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Wind energy Frequently Asked Questions". British Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ Forest clearance for Meyersdale, Pa., wind power facility

- ^ The negative effects of windfarms on birds and other wildlife: articles by Mark Duchamp

- ^ "Birds". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ Lomborg, Bjørn (2001). The Skeptical Environmentalist. New York City: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Emma Marris (10 May 2007). ""Wind farms' deadly reputation hard to shift"". Nature. pp. 447 126. doi:10.1038/447126a. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Subscription required. - ^ "Wind farms". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 14 September 2005. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Wind turbines a breeze for migrating birds". New Scientist (2504): 21. 2005. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Developing Methods to Reduce Bird Mortality In the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area

- ^ Wind power and birds at Smøla [Norway 2003-2006]

- ^ Sea eagles being killed by wind turbines

- ^ "Caution Regarding Placement of Wind Turbines on Wooded Ridge Tops" (PDF). Bat Conservation International. 4 January 2005. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Arnett, Edward B. (June 2005). "Relationships between Bats and Wind Turbines in Pennsylvania and West Virginia: An Assessment of Fatality Search Protocols, Patterns of Fatality, and Behavioral Interactions with Wind Turbines" (PDF). Bat Conservation International. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Pollution at Lough Lee: Wind farm under investigation as wild trout stocks disappear". Ulster Herald. 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Monasette (2003-10-19). "Landslide". North Atlantic Skyline. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ ""Ocean Noise: What We Learned in 2006"". Acoustic Ecology Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gipe, Paul (2007). "A Summary of Fatal Accidents in Wind Energy". Wind-Works.org. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Gipe, Paul (2006). "Contemporary Mortality (Death) Rates in Wind Energy". Wind-Works.org. Retrieved 2007-12-30. - Table of fatalities, Microsoft Excel format (pro-wind power)

- ^ a b c d Craig, David (2007-11-30). "Summary of Wind Turbine Accident data". Caithness Windfarm Information Forum. Retrieved 2007-12-30. - Table of accidents, PDF format (anti-wind power)

- ^ [2] (German)

- ^ "Lightning Damage". NGup Rotor Blades. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ ""Send us your burnouts. We accept trade-ins."". Moorsyde Wind Farm Action Group. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.windaction.org/pictures/c51/

- ^ "Wind Turbine Accidents Database" (in Template:De icon). 2007-11-26. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Experts try to determine wind farm blaze cause". ABC South East SA. 2006-01-23. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Edenhope and Ngarkat fires". Naracoorte Herald. 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Gipe, Paul (1995). Wind Energy Comes of Age. John Wiley and Sons. p. 560. ISBN 047110924X.

The total mortality rate, admittedly based on scanty data from a young technology, is 0.23 death per terawatt-hour.

- ^

Gipe, Paul (2006). "Contemporary Mortality (Death) Rates in Wind Energy". Wind-Works.org. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

I reported in Wind Energy comes of Age a mortality rate of 0.27 deaths per TWh. However ... in the mid-1990s the mortally rate was actually 0.4 per TWh.

- ^ Severe Accidents in the Energy Sector, Paul Scherrer Institut, 2001 [3]

- ^ Rod Thompson (May 20, 2006). ""Wind turbine lights have opponents seeing sparks"". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dana Childs (December 20, 2006). ""Wind energy scores major legal victory in U.S."". Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ Opposition to Cape Cod wind farms.

- ^ Land slide in Galway, Ireland during wind farm construction.

- ^ Texas lawsuit to block south Texas wind farms.

- ^ Lawsuit for bird deaths.

- ^ O'Malley weighs western windmills; The Washington Times.

Wind power projects

- Database of projects throughout the United States

- Database of projects throughout the whole World

- Altamont Pass

- Cape Wind (Massachusetts)

- Gharo Wind Power Plant in Pakistan

- Wind power in Denmark

- Wind power in Spain

- Wind power in Germany

- Wind power in Australia

- Wind power in the United Kingdom

- Wind power in the United States

- Renewable energy in Scotland

- Database of offshore wind projects in North America