Zoot Suit Riots

| Zoot Suit Riots | |

|---|---|

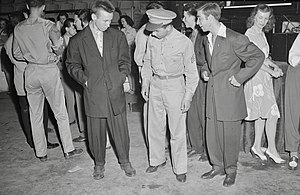

Zoot suits in 1942 | |

| Date | 1943 |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Conflict between American servicemen stationed in Southern California and Mexican-American youths |

| Methods | Widespread rioting |

The Zoot Suit Riots were a series of racial attacks in 1943 during World War II that broke out in Los Angeles, California, during a period when many Mexican migrants arrived for the defense effort and newly assigned servicemen flooded the city. United States sailors and Marines attacked Mexican youths, recognizable by the zoot suits they favored, as being unpatriotic. American military personnel and Mexicans were the main parties in the riots; servicemen attacked some African American and Filipino/Filipino American youths as well, who also took up the zoot suits.[1] The Zoot Suit Riots were related to fears and hostilities aroused by the coverage of the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial, following the killing of a young Latino man in a barrio near Los Angeles. The riot appeared to trigger similar attacks that year against Latinos in Chicago, San Diego, Oakland, Evansville, Philadelphia, and New York City.[2][page needed]

History

The zoot suit riots began in Los Angeles, California during a period of rising tensions between American servicemen stationed in Southern California and Mexican-American youths in the city, which had a large ethnic Mexican-American population.

Although Mexican-American men were over-represented in the military as a percentage of their population,[3] many Americans in military service resented the sight of young Latinos wearing clothing which they considered extravagant (and therefore unpatriotic) during wartime after clothing restrictions had been published.[4][5] Many of the servicemen were from areas of the country with little experience or knowledge of Mexican-American culture.

Origins

During the early 20th century, many Mexicans immigrated for work to such areas as Texas, Arizona, and California.[6] They encountered other Mexican Americans whose ancestors had been there for centuries prior to the United States' acquisition of these territories. Both groups were often restricted by discrimination to lower-level jobs, including as migrant workers in the large agricultural industry, or laborers in cities.

During the Great Depression, in the early 1930s the United States deported more than 12,000 people of Mexican descent—including many American citizens[7]—to Mexico (see Mexican Repatriation), to reduce calls on limited American resources. By the late 1930s about 3 million Mexican Americans resided in the United States. Because of its history as part of the Spanish Empire, Los Angeles had the highest concentration of Mexicans outside Mexico.[8]

As early residents, the Latinos occupied historic areas. In addition, they had long been informally segregated and restricted to an area of the city with the oldest, most run-down housing.[8] Job discrimination in Los Angeles forced many Mexicans to work for below-poverty level wages.[9][10] The Los Angeles newspapers described Mexicans by using racially inflammatory propaganda, suggesting a problem with juvenile delinquency.[11][12][13] These factors caused much racial tension between Mexicans and whites.[14]

During the late 1930s young Latinos in California, for whom the media usually used the then-derogatory term Chicanos (which some Mexican Americans today adopt as self-identity), created a youth culture.[15][16]

Lalo Guerrero became known as the father of Chicano music, as the young people adopted a music, language and dress of their own. Young men wore zoot suits—a flamboyant long jacket with baggy pegged pants, sometimes accessorized with a pork pie hat, a long watch chain, and shoes with thick soles. They called themselves "pachucos." In the early 1940s, arrests of Mexican-American youths and negative stories in the Los Angeles Times fueled a perception that these pachuco gangs were delinquents who were a threat to the broader community.[17] Some African-American youth also were part of zoot-suit culture.

In the summer of 1942 the Sleepy Lagoon murder case made national news; nine teenage members of the 38th Street Gang were accused of murdering a man named José Díaz in an abandoned quarry pit. The nine defendants were convicted at trial and sentenced to long prison terms. Eduardo Obregón Pagán wrote,

"Many Angelenos saw the death of José Díaz as a tragedy that resulted from a larger pattern of lawlessness and rebellion among Mexican American youths, discerned through their self-conscious fashioning of difference, and increasingly called for stronger measures to crack down on juvenile delinquency."[18]

The convictions of the nine young men were ultimately overturned, but the case generated much animosity within the white community toward Mexican Americans. The police and press characterized all Mexican youths as "pachuco hoodlums and baby gangsters."[19][20]

With the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the nation had to deal with the restrictions of rationing and the prospects of conscription. In March 1942, the War Production Board's regulated the manufacture of mens' suits and indeed all clothing which contained wool. To achieve a 26% cut-back in the use of fabrics, the War Production Board drew up regulations for the manufacture of what Esquire magazine called, "streamlined suits by Uncle Sam."[21] The regulations effectively forbade the manufacture of the wide-cut zoot suits and full women's skirts or dresses. Most legitimate tailoring companies ceased to manufacture or advertise any suits that fell outside the War Production Board's guidelines.

But the demand for zoot suits did not decline; a network of bootleg tailors based in Los Angeles and New York City continued to produce the garments, and youths also continued to wear clothes that they already owned. Servicemen and zoot suiters in Los Angeles were immediately identifiable by their dress. Some whites thought that the continued wearing of zoot suits represented the youths' public flouting of rationing regulations. Officials began to cast wearing of zoot suits in moral terms, associating it with petty crime, violence and the snubbing of national wartime rules.[17]

Immediate run-up to the riots

Following the Sleepy Lagoon case, U.S. service personnel got into violent altercations with young Mexican Americans in zoot suits in San Jose, Oakland, San Diego, Delano, Los Angeles, and lesser cities and towns in California. During this period, the immense defense buildup attracted tens of thousands of new workers to major installations, including many African Americans in the second wave of the Great Migration.

The most serious ethnic conflicts erupted in Los Angeles. Two altercations between military personnel and zoot suiters catalyzed the larger riots. The first occurred on May 30, 1943, four days before the start of the riots. A dozen sailors and soldiers, including Seaman Second Class Joe Dacy Coleman, were walking down Main Street in Los Angeles when they spotted a group of women on the opposite side. The group, except for Coleman, crossed the street to speak to the women. Coleman continued, walking past two zoot suiters when one of them raised his arm, so he turned and grabbed it. A fight broke out during which the sailor was struck in the back of the head, falling unconscious to the ground, breaking his jaw in two places. On the opposite side of the street, five young men attacked the group of servicemen for trying to talk to the women. The other servicemen fought their way back to Coleman and dragged him to safety.[22]

Four nights later on June 3, 1943, another incident erupted. About eleven sailors got off a bus and started walking along Main Street in Downtown Los Angeles. Encountering a group of young Mexicans in zoot suits, they got into a verbal argument. The sailors told police that they were jumped and beaten by this gang. The Los Angeles Police Department responded to the incident, including many off-duty officers who identified as the Vengeance Squad. The officers went to the scene "seeking to clean up Main Street from what they viewed as the loathsome influence of pachuco gangs."[23]

The next day, 200 members of the U.S. Navy got a convoy of about 20 taxicabs and headed for East Los Angeles, the center of Mexican settlement. The sailors spotted a group of young zoot suiters and assaulted them with clubs. They stripped the boys of the zoot suits and burned the tattered clothes in a pile. They attacked and stripped everyone they came across who were wearing zoot suits. The Zoot Suit Riots spread.[23]

The riots

As the violence escalated over the ensuing days, thousands of white servicemen joined the attacks, marching abreast down streets, entering bars and movie houses, and assaulting any young Latino males they encountered. In one incident, sailors dragged two zoot suiters on-stage as a film was being screened, stripped them in front of the audience, and then urinated on their suits.[17] Although police accompanied the rioting servicemen, they had orders not to arrest any. After several days, more than 150 people had been injured and police had arrested more than 500 Latinos on charges ranging from "rioting" to "vagrancy".[5]

A witness to the attacks, journalist Carey McWilliams wrote,

Marching through the streets of downtown Los Angeles, a mob of several thousand soldiers, sailors, and civilians, proceeded to beat up every zoot suiter they could find. Pushing its way into the important motion picture theaters, the mob ordered the management to turn on the house lights and then ran up and down the aisles dragging Mexicans out of their seats. Streetcars were halted while Mexicans, and some Filipinos and Negroes, were jerked from their seats, pushed into the streets and beaten with a sadistic frenzy.[24]

The local white press lauded the attacks by the servicemen, describing the assaults as having a "cleansing effect" to rid Los Angeles of "miscreants" and "hoodlums".[25] As the riots progressed, the media reported the arrest of Amelia Venegas, a female zoot suiter charged with carrying a brass knuckleduster. While the revelation of female pachucos' (pachucas) involvement in the riots led to frequent coverage of the activities of female pachuco gangs, the media suppressed any mention of the European -American pachuco gangs that were also involved.[17]

The Los Angeles City Council approved a resolution criminalizing the wearing of "zoot suits with reat [sic] pleats within the city limits of LA" after Councilman Norris Nelson stated, "The zoot suit has become a badge of hoodlumism." No ordinance was approved by the City Council or signed into law by the Mayor, although the council encouraged the War Production Board to take steps "to curb illegal production of men's clothing in violation of WPB limitation orders."[5] While sailors and Marines had first targeted only pachucos, they also attacked African Americans in zoot suits who lived in the Central Avenue corridor area. The Navy and Marine Corps command staffs intervened on June 7 to reduce the attacks, confining sailors and Marines to barracks and declaring Los Angeles off limits to all military personnel, with enforcement by U.S. Navy Shore Patrol personnel. Their official position continued to be that their men were acting in self defense.[5]

By the middle of June, the riots in Los Angeles were dying out, but other riots erupted in other cities in California, as well as in cities in Texas and Arizona. Related incidents broke out in northern cities such as Detroit, New York City, and Philadelphia, where two members of Gene Krupa's dance band were beaten up for wearing zoot suit stage costumes. A zoot suit riot at Cooley High School in Detroit, Michigan was initially dismissed as an "adolescent imitation" of the Los Angeles riots. But, within weeks, Detroit was in the midst of the worst race riot in its history in which whites attacked African Americans and destroyed much of their neighborhood.[17]

Reactions

As the riots subsided, nation-wide public condemnation of the military and civil officials followed. The most urgent concern of officials, however, was relations with Mexico, as the economy of Southern California relied on the importation of Mexican labor to assist in the harvesting of California crops. After the Mexican Embassy lodged a formal protest with the State Department, Governor Earl Warren of California ordered the creation of the McGucken committee to investigate and determine the cause of the riots.[17] In 1943, the committee issued its report; it determined racism to be a central cause of the riots, further stating that it was "an aggravating practice (of the media) to link the phrase zoot suit with the report of a crime." The governor appointed the Peace Officers Committee on Civil Disturbances, chaired by Robert W. Kenny, president of the National Lawyers Guild to make recommendations to the police.[26] Human relations committees were appointed and police departments were required to train their officers to treat all citizens equally.[27] At the same time, Mayor Fletcher Bowron came to his own conclusion. The riots, he said, were caused by Mexican juvenile delinquents and by white Southerners, a group arising out of a region in which both overt legal and socially sanctioned white racial discrimination held sway until the 1960s. Racial prejudice, according to Mayor Bowron, was not a factor.[27]

A week later, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt commented on the riots, which the local press had largely attributed to criminal actions by Mexican Americans, in her newspaper column. "The question goes deeper than just suits. It is a racial protest. I have been worried for a long time about the Mexican racial situation. It is a problem with roots going a long way back, and we do not always face these problems as we should." – June 16, 1943[27]

This led to an outraged response from the Los Angeles Times which printed an editorial the following day, in which it accused Mrs. Roosevelt of having communist leanings and stirring "race discord".[28]

On June 21, 1943, the State Un-American Activities Committee under State Senator Jack Tenney arrived in Los Angeles with orders to "determine whether the present Zoot Suit Riots were sponsored by Nazi agencies attempting to spread disunity between the United States and Latin-American countries." Although Tenney claimed he had evidence the riots were "[A]xis-sponsored", the evidence was never presented, although the claims were supported in the minds of the public by Japanese propaganda broadcasts accusing the United States' government of ignoring the brutality of U.S. Marines toward Mexicans. In late 1944, ignoring the findings of the McGucken committee and the unanimous reversal of the convictions in the Sleepy Lagoon case on October 4, the Tenney Committee announced that the National Lawyers Guild was an "effective communist front."[17][26]

Many post-war activists such as Luis Valdez, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright have claimed that they were inspired by the Zoot Suit Riots. Cesar Chávez was a zoot suiter when he first became interested in politics and zoot suiter Malcolm X took part in the Harlem zoot suit riots.[17]

In popular culture

- In the 3rd season of the sitcom, The Big Bang Theory, episode 12 "The Psychic Vortex," there is a mention of the Zoot Suit Riots.

- The Zoot Suit Riots form the backdrop for the events in the play Zoot Suit and the film based on the play.

- The 1997 song Zoot Suit Riot (song) by the Cherry Poppin' Daddies revolves around the riots.

- The movie 1941 included a riot between servicemen and youths sporting zoot suits (referring to the 1943 riot; another anachronism was a portrayal of the Great Los Angeles Air Raid).

- The riots are featured in the prologue of the James Ellroy novel, The Black Dahlia. A flashback scene in The Black Dahlia film takes place during the Zoot Suit Riots.

- The film American Me opened with a depiction of the riots.

- The 2011 video game L.A. Noire mentions the event during the "Traffic" segment of the game, where the protagonist's partner Stefan Bekowsky notes earning a bravery citation during the "zooter riots."

- The riots are mentioned in Toni Morrison's 2012 novel Home, wherein Frank Money also imagines seeing a man in a zoot suit.

See also

- Battle of Brisbane, Australia, 1942

- Battle of Manners Street in Wellington, New Zealand, 1943

- History of the Mexican Americans in Los Angeles

References

- ^ Viesca, Victor Hugo (January 2003). "With Style: Filipino Americans, and the Making of American Urban Culture". our own voice. Retrieved 2013-01-28. (originally delivered as a talk at the 9th Biennial Filipino American National Historical Society Conference in Los Angeles on July 27, 2002.)

- ^ Novas, Himilce (2007). "Mexican Americans". Everything you need to know about Latino history (2008 ed.). New York: Plume. p. 98. ISBN 9780452288898. LCCN 2007032941.

- ^ some 500,000 Mexican Americans served in the U.S. armed services (around 17% of their population compared to under 10% for the general public) where they had the highest percentage of Congressional Medal of Honor winners (17) of any minority in the United States. Between 1942 and 1967, over four million Mexicans and Puerto Ricans were contracted by the United States under the Bracero Program to alleviate the labor shortage caused by WWII.

- ^ Osgerby, Bill (2008). "Understanding the 'Jackpot Market': Media, Marketing, and the Rise of the American Teenager". In Patrick L. Jamieson & Daniel Romer, eds (ed.). The Changing Portrayal of Adolescents in the Media Since 1950. Nfvvzcew York: Oxford University Press US. pp. 31–32. ISBN 0-19-534295-X.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d "Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots", Los Angeles Almanac

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Census (1960). "C". Historical statistics of the United States: colonial times to 1957. Vol. 62. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Govt. Print Off., 1960. pp. 57–58. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin R. (2005). "The Forgotten 'Repatriation' of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the 'War on Terror'". Pace Law Review. 26 (1): 1–26.

- ^ a b Obregón Pagán, Eduardo (June 3, 2009). "2". Murder at The Sleepy Lagoon. ReadHowYouWant.com. pp. 23–28. ISBN 1-4429-9501-7.

- ^ Reisler, Mark (1976). By the Sweat of Their Brow: Mexican Immigrant Labor in the United States, 1900-1940. Greenwood Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 0-8371-8894-6. OCLC 2121388.

Mexican workers helped fulfill the unskilled labor needs of American industry as well as agriculture. Noting their availability at a time of declining European immigration and their willingness to accept low wages, non-agricultural employers began to rely upon Mexican workers as early as World War I.

- ^ Ryan, James Gilbert; Schlup, Leonard C. (2006). Historical dictionary of the 1940s. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 250–251. ISBN 0-7656-0440-X.

The establishment of the Fair Employment Office and Coordinating Committee on Latin American Affairs and the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs dealt specifically with Mexican American concerns. The prevailing racial violence ensured that federal efforts would continue, but discrimination lived on. By 1945, however, reforms were no longer deemed necessary [by the government]; protective innovations ceased, yet migration continued

- ^ Carey, McWilliams; Stewart, Dean; Gendar, Jeannine (2001). Fool's Paradise: A Carey McWilliams Reader. Heyday Books. pp. 180–183. ISBN 1-890771-41-4.

To appreciate the social significance of the Sleepy Lagoon case, it is necessary to have a picture of the concurrent events. The anti-Mexican press campaign which had been whipped up through the spring and early summer of 1942 finally brought recognition, from the officials, of the existence of an 'awful' situation in reference to 'Mexican juvenile delinquency.'

- ^ Obregón Pagán, Eduardo (June 3, 2009). Murder at The Sleepy Lagoon. ReadHowYouWant.com. pp. 130–132. ISBN 9781442995017.

In the early stages of the grand jury investigation, many of the larger newspapers devoted no more than a few brief lines to [the Sleepy Lagoon trial]. Yet from the beginning, the Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express latched on to the term 'Sleepy Lagoon' and immediately turned it on the accused youths. 'Goons of Sleepy Lagoon' was a favorite moniker that skewed the brief and otherwise bland reporting of the grand jury investigation and subsequent trial.

- ^ Rule, James B (1989). Theories of Civil Violence. Vol. 1. University of California Press. pp. 102–108.

The authors surveyed references to Mexicans in the Los Angeles Times during the period leading up to that city's anti-Mexican riots of 1943; these events were called 'zoot suit riots' at the time. Turner found that, as the riots approached, newspaper references to 'zoot suiters' rose whereas other references to Mexicans bearing less emotional and negative connotations declined. The zoot suit had become a symbol or code expression for the 'bad' Mexican, even though it appeared that few of the Mexican youths involved in the riots actually wore the notorious outfit.

- ^ Solomon, Larry. Roots of Justice Stories of Organizing in Communities of Color. New York: Chardon, 1998. Pg 22.

- ^ Ruiz, Vicki L.; Korrol, Virginia Sanchez, eds. (2006). Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press.[page needed]

Long a disparaging term in Mexico, the term Chicano gradually transformed from a class-based term of derision to one of ethnic pride and general usage within Mexican-American communities beginning with the rise of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. - ^ Herrera-Sobek, Maria (2006). Chicano folklore: a handbook. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313333255. LCCN 2006000652.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cosgrove, Stuart (1984). "The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare". History Workshop Journal. 18: 77–91. doi:10.1093/hwj/18.1.77.

- ^ Pagán, Eduardo Obregón (2006). Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, and Riot in Wartime L.A. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 145. ISBN 0807828262. LCCN 2003048891.

- ^ del Castillo, Richard Griswold (2000). "The Los Angeles 'Zoot Suit Riots' Revisited: Mexican and Latin American Perspectives". Mexican Studies. 16 (2): 367–91. doi:10.1525/msem.2000.16.2.03a00080. JSTOR 1052202.

- ^ Pagan (2006). Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon, Pg. 159.

- ^ Schoeffler, O. E.; William Gale (1973). Esquire’s encyclopedia of 20th century men’s fashions. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 24. ISBN 0070554803. LCCN 72009811.

- ^ Pagán, Eduardo O. (2000). "Los Angeles Geopolitics and the Zoot Suit Riot, 1943". Social Science History. 24 (1): 223–256 [pp. 242–243]. doi:10.1215/01455532-24-1-223.

- ^ a b Alvarez, Luis A. (2001). The Power of the Zoot: Race, Community, and Resistance in American Youth Culture, 1940-1945. Austin: University of Texas. p. 204.

- ^ McWilliams, Carey (1990). North from Mexico: The Spanish-speaking People of the United States. Contributions in American History. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-26631-7.[page needed]

- ^ McWilliams, Carey (2001). "Blood on the Pavements". Fool's Paradise: A Carey McWilliams Reader. Heyday Books. ISBN 978-1-890771-41-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b My first forty years in california politics, 1922-1962 oral history transcript Robert W. Kenny[page needed]

- ^ a b c "Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots". Los Angeles Almanac. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Eduardo Obregón Pagán. Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, and Riot in Wartime L.A. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2004.[page needed]

Further reading

- Alvarez, Luis. The Power of the Zoot: Youth Culture and Resistance During World War II (University of California Press, 2008)

- del Castillo, Richard Griswold (2000). "The Los Angeles 'Zoot Suit Riots' Revisited: Mexican and Latin American Perspectives". Mexican Studies. 16 (2): 367–91. doi:10.1525/msem.2000.16.2.03a00080. JSTOR 1052202.

- Mazon, Maurizio. The Zoot-Suit Riots: The Psychology of Symbolic Annihilation. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX. 2002 ISBN 0-292-79803-2 ISBN 9780292798038

- Pagan, Eduardo Obregon (2000). "Los Angeles Geopolitics and the Zoot Suit Riot, 1943". Social Science History. 24: 223–56. doi:10.1215/01455532-24-1-223.

- Pagán, Eduardo Obregón. Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race & Riots in Wartime L.A. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2003. ISBN 0-8078-5494-8 ISBN 9780807854945

- Zoot Suit Riots. American Experience series, produced by Joseph Tovares. WGBH Boston, 2001. 60 mins. PBS Video.

External links

- Zoot Suit Riots. American Experience.

- A list of newspaper articles written about the Zoot Suit Riots.

- Images and primary source documents about the Zoot Suit Riots, from the University of California

- Cosgrove, Stuart (1984). "The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare". History Workshop Journal. 18: 77–91. doi:10.1093/hwj/18.1.77.

- 1943 riots

- 1943 in the United States

- 1943 crimes in the United States

- Hispanic and Latino-American working class

- History of youth

- Riots and civil disorder in California

- Mexican-American history

- Mexican-American culture in Los Angeles, California

- White American riots in the United States

- Clothing controversies

- 1940s fashion

- 1943 in California

- History of racism in California

- Crimes in Los Angeles, California