Communication: Difference between revisions

| [accepted revision] | [accepted revision] |

changed section order bring the related sections together |

→Works cited: added sources |

||

| Line 216: | Line 216: | ||

===Works cited=== |

===Works cited=== |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Barnlund |first1=Dean C. |editor1-last=Akin |editor1-first=Johnnye |editor2-last=Goldberg |editor2-first=Alvin |editor3-last=Myers |editor3-first=Gail |editor4-last=Stewart |editor4-first=Joseph |title=Language Behavior |date=5 July 2013 |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |isbn=9783110878752 |pages=43–61 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110878752.43/html?lang=en |language=en |chapter=A Transactional Model of Communication}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Barnlund |first1=Dean C. |editor1-last=Akin |editor1-first=Johnnye |editor2-last=Goldberg |editor2-first=Alvin |editor3-last=Myers |editor3-first=Gail |editor4-last=Stewart |editor4-first=Joseph |title=Language Behavior |date=5 July 2013 |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |isbn=9783110878752 |pages=43–61 |url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110878752.43/html?lang=en |language=en |chapter=A Transactional Model of Communication}} |

||

*{{cite book |last1=Chandler |first1=Daniel |last2=Munday |first2=Rod |title=A Dictionary of Media and Communication |date=10 February 2011 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=9780199568758 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nLuJz-ZB828C |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Danesi |first1=Marcel |title=Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, Media, and Communications |date=1 January 2000 |publisher=University of Toronto Press |isbn=9780802083296 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n6XFBxvLzk0C |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Danesi |first1=Marcel |title=Encyclopedia of Media and Communication |date=17 June 2013 |publisher=University of Toronto Press |isbn=9781442695535 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GZOBAAAAQBAJ |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Littlejohn |first1=Stephen W. |last2=Foss |first2=Karen A. |title=Encyclopedia of Communication Theory |date=18 August 2009 |publisher=SAGE Publications |isbn=9781412959377 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2veMwywplPUC |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Schement |first1=Jorge Reina |title=Encyclopedia of Communication and Information |date=2002 |publisher=Macmillan Reference USA |isbn=9780028653853 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cQgjAQAAIAAJ |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Håkansson |first1=Gisela |last2=Westander |first2=Jennie |title=Communication in Humans and Other Animals |date=2013 |publisher=John Benjamins Publishing Company |isbn=9789027204585 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MAibmQEACAAJ |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Baluška |first1=František |last2=Ninkovic |first2=Velemir |title=Plant Communication from an Ecological Perspective |date=5 August 2010 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=9783642121623 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9hUpvAoY_HAC&pg=PA1 |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Berea |first1=Anamaria |title=Emergence of Communication in Socio-Biological Networks |date=16 December 2017 |publisher=Springer |isbn=9783319645650 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OIhDDwAAQBAJ |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last1=Steinberg |first1=Sheila |title=An Introduction to Communication Studies |date=2007 |publisher=Juta and Company Ltd |isbn=9780702172618 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g8GRgXYeo_kC&pg=PA286 |language=en}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 17:52, 20 December 2022

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Communication |

|---|

|

| General aspects |

| Fields |

| Disciplines |

| Categories |

Communication (from Latin: communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with")[1][2][3] is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inquiry studying them. There are many disagreements about its precise definition.[4][5] John Peters argues that the difficulty of defining communication emerges from the fact that communication is both a universal phenomenon and a specific discipline of institutional academic study.[6] One definitional strategy involves limiting what can be included in the category of communication (for example, requiring a "conscious intent" to persuade).[7] By this logic, one possible definition of communication is the act of developing meaning among entities or groups through the use of sufficiently mutually understood signs, symbols, and semiotic conventions.

An important distinction is between verbal communication, which happens through the use of a language, and non-verbal communication, for example, through gestures or facial expressions. Models of communication try to provide a detailed explanation of the different steps and entities involved. An influential model is given by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver, who argue that communicative motivation prompts the sender to compose a message, which is then encoded and transmitted. Once it has reached its destination, it is decoded and interpreted by the receiver.[8][9][10] Communication is studied in various fields. Information theory investigates the quantification, storage, and communication of information in general. Communication studies is concerned with human communication, while the science of biocommunication is interested in any form of communication between living organisms.

Communication can be realized visually (through images and written language) and through auditory, tactile/haptic (e.g. Braille or other physical means), olfactory, electromagnetic, or biochemical means (or any combination thereof). Human communication is unique in its extensive use of abstract language.

Definitions

Communication is usually understood as the transmission of information.[11][12][13] In this regard, a message is conveyed from a sender to a receiver using some form of medium, such as sound, paper, bodily movements, or electricity.[14][15][16] In a different sense, the term "communication" can also refer just to the message that is being communicated or to the field of inquiry studying such transmissions.[11][13] There is a lot of disagreement concerning the precise characterization of communication and various scholars have raised doubts that any single definition can capture the term accurately. These difficulties come from the fact that the term is applied to diverse phenomena in different contexts, often with slightly different meanings.[17][18] Despite these problems, the question of the right definition is of great theoretical importance since it affects the research process on all levels. This includes issues like which empirical phenomena are observed, how they are categorized, which hypotheses and laws are formulated as well as how systematic theories based on these steps are articulated.[17] The word "communication" has its root in the Latin verb "communicare", which means "to share" or "to make common".[14]

Some theorists give very broad definitions of communication that encompass unconscious and non-human behavior.[17] In this regard, many animals communicate within their own species and even plants like flowers may be said to communicate by attracting bees.[14] Other researchers restrict communication to conscious interactions among human beings.[17][14] Some definitions focus on the use of symbols and signs while others emphasize the role of understanding, interaction, power, or transmission of ideas. Various characterizations see the communicator's intent to send a message as a central component. On this view, the transmission of information is not sufficient for communication if it happens unintentionally.[17] An important version of this view is given by Paul Grice, who identifies communication with actions that aim to make the recipient aware of the communicator's intention.[19] One question in this regard is whether only the successful transmission of information should be regarded as communication.[17] For example, distortion may interfere and change the actual message from what was originally intended.[15] A closely related problem is whether acts of deliberate deception constitute communication.[17]

According to an influential and broad definition by I. A. Richards, communication happens when one mind acts upon its environment in order to transmit its own experience to another mind.[18][20] Another important characterization is due to Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver. On their view, communication involves the interaction of several components, such as a source, a message, an encoder, a channel, a decoder, and a receiver.[18] The paradigmatic form of communication happens between two or several individuals. However, it can also take place on a larger level, for example, between organizations, social classes, or nations.[14] Niklas Luhmann rejects the view that communication is, on its most fundamental level, an interaction between two distinct parties. Instead, he holds that "only communication can communicate" and tries to provide a conceptualization in terms of autopoietic systems without any reference to consciousness or life.[21] John Peters sees communication as "an apparent answer to the painful divisions between self and other, private and public, and inner thought and outer world."[22]

Communication models

Models of communication are conceptual representations of the process of communication.[23] Their goal is to provide a simplified overview of its main components. This makes it easier for researchers to formulate hypotheses, apply communication-related concepts to real-world cases, and test predictions.[24][25] However, it is often argued that many models lack the conceptual complexity needed for a comprehensive understanding of all the essential aspects of communication. They are usually presented visually in the form of diagrams showing various basic components and their interaction.[26][24][27]

Models of communication are often categorized based on their intended applications and how they conceptualize communication. Some models are general in the sense that they are intended for all forms of communication. They contrast with specialized models, which aim to describe only certain forms of communication, like models of mass communication.[28] An influential classification distinguishes between linear transmission models, interaction models, and transaction models.[25][29][24] Linear transmission models focus on how a sender transmits information to a receiver. They are linear because this flow of information only goes in one direction.[26][30] This view is rejected by interaction models, which include a feedback loop. Feedback is required to describe many forms of communication, such as a regular conversation, where the listener may respond by expressing their opinion on the issue or by asking for clarification. For interaction models, communication is a two-way-process in which the communicators take turns in sending and receiving messages.[26][30][31] Transaction models further refine this picture by allowing sending and responding to happen at the same time. This modification is needed, for example, to describe how the listener in a face-to-face conversation gives non-verbal feedback through their body posture and their facial expressions while the other person is talking. Transaction models also hold that meaning is produced during communication and does not exist independent of it.[31][26][32]

All the early models, developed in the middle of the 20th century, are linear transmission models. Lasswell's model, for example, is based on five fundamental questions: "Who?", "Says What?", "In What Channel?", "To Whom?", and "With What Effect?".[28][33][34] The goal of these questions is to identify the basic components involved in the communicative process: the sender, the message, the channel, the receiver, and the effect.[35][36][37] Lasswell's model was initially only conceived as a model of mass communication, but it has been applied to various other fields as well. Some theorists have expanded it by including additional questions, like "Under What Circumstances?" and "For What Purpose?".[38][39][40]

The Shannon–Weaver model is another influential linear transmission model.[41][24][42] It is based on the idea that a source creates a message, which is then translated into a signal by a transmitter. Noise may interfere and distort the signal. Once the signal reaches the receiver, it is translated back into a message and made available to the destination. For a landline telephone call, the person calling is the source and their telephone is the transmitter. It translates the message into an electrical signal that travels through the wire, which acts as the channel. The person taking the call is the destination and their telephone is the receiver.[43][41][44] The Shannon–Weaver model includes an in-depth discussion of how noise can distort the signal and how successful communication can be achieved despite noise. This can happen, for example, by making the message partially redundant so that decoding is possible nonetheless.[43][45][46] Other influential linear transmission models include Gerbner's model and Berlo's model.[47][48][49]

The earliest interaction model is due to Wilbur Schramm.[31][50][51] For him, communication starts when a source has an idea and expresses it in the form of a message. This process is called encoding and happens using a code, i.e. a sign system that is able to express the idea, for example, through visual or auditory signs.[52][31][53] The message is sent to a destination, who has to decode and interpret it in order to understand it.[54][53] In response, they formulate their own idea, encode it into a message and send it back as a form of feedback. Another important innovation of Schramm's model is that previous experience is necessary to be able to encode and decode messages. For communication to be successful, the fields of experience of source and destination have to overlap.[52][55][53]

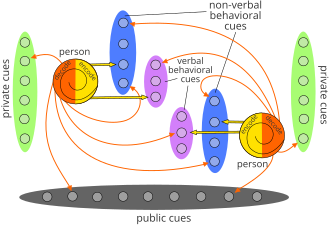

The first transactional model was proposed by Dean Barnlund. He understands communication as "the production of meaning, rather than the production of messages".[56] Its goal is to decrease uncertainty and arrive at a shared understanding.[57][58][59] This happens in response to external and internal cues. Decoding is the process of ascribing meaning to them and encoding consists in producing new behavioral cues as a response.[58][60][61]

Human

There are many forms of human communication. Important distinctions concern whether language is used, as in the contrast between verbal and non-verbal communication, and whether one communicates with others or with oneself, as in the contrast between interpersonal and intrapersonal communication.[62][63] The field studying human communication is known as anthroposemiotics.[64]

Mediums

Verbal

Verbal communication is the spoken or written conveyance of a message. Human language can be defined as a system of symbols (also known as lexemes) and the grammars (rules) by which the symbols are manipulated. The word "language" also refers to common properties of languages. Language learning normally occurs most intensively during human childhood. Most of the large number of human languages use patterns of sound or gesture for symbols which enable communication with others around them. Languages tend to share certain properties, although there are exceptions. Constructed languages such as Esperanto, programming languages, and various mathematical formalisms are not necessarily restricted to the properties shared by human languages.[citation needed]

Communicators' diverse efforts to produce and interpret meaning in language are functionally constrained by that language's prototypical phonology (sounds that typically appear in a language), morphology (what counts as a word), syntax (word-order), semantics (conventional meaning of words), and pragmatics (which meanings are conventional to which contexts).[citation needed]

The meanings that are attached to words can be literal, or otherwise known as denotative; relating to the topic being discussed, or, the meanings take context and relationships into account, otherwise known as connotative; relating to the feelings, history, and power dynamics of the communicators.[65]

Contrary to popular belief, signed languages of the world (e.g., American Sign Language) are considered to be verbal communication because their sign vocabulary, grammar, and other linguistic structures abide by all the necessary classifications as spoken languages. There are however, nonverbal elements to signed languages, such as the speed, intensity, and size of signs that are made. A signer might sign "yes" in response to a question, or they might sign a sarcastic-large slow yes to convey a different nonverbal meaning. The sign yes is the verbal message while the other movements add nonverbal meaning to the message.[citation needed]

Written form

Over time the forms of and ideas about communication have evolved through the continuing progression of technology. Advances include communications psychology and media psychology, an emerging field of study.[citation needed]

The progression of written communication can be divided into three "information communication revolutions":[66]

- Written communication first emerged through the use of pictographs. The pictograms were made in stone, hence written communication was not yet mobile. Pictograms began to develop standardized and simplified forms.

- The next step occurred when writing began to appear on paper, papyrus, clay, wax, and other media with commonly shared writing systems. Communication became mobile.

- The final stage is characterized by the transfer of information through controlled waves of electromagnetic radiation (i.e., radio, microwave, infrared) and other electronic signals.

Communication is thus a process by which meaning is assigned and conveyed in an attempt to create shared understanding. Gregory Bateson called it "the replication of tautologies in the universe.[67] This process, which requires a vast repertoire of skills in interpersonal processing, listening, observing, speaking, questioning, analyzing, gestures, and evaluating enables collaboration[68][69] and cooperation.[70][71]

Non-verbal

Nonverbal communication explains the processes that convey a type of information in a form of non-linguistic representations. Examples of nonverbal communication include haptic communication, chronemic communication, gestures, body language, facial expressions, eye contact etc. Nonverbal communication also relates to the intent of a message. Examples of intent are voluntary, intentional movements like shaking a hand or winking, as well as involuntary, such as sweating.[72] Speech also contains nonverbal elements known as paralanguage, e.g. rhythm, intonation, tempo, and stress. It affects communication most at the subconscious level and establishes trust. Likewise, written texts include nonverbal elements such as handwriting style, the spatial arrangement of words and the use of emoticons to convey emotion.

Nonverbal communication demonstrates one of Paul Watzlawick's laws: you cannot not communicate. Once proximity has formed awareness, living creatures begin interpreting any signals received.[73] Some of the functions of nonverbal communication in humans are to complement and illustrate, to reinforce and emphasize, to replace and substitute, to control and regulate, and to contradict the denotative message.

Nonverbal cues are heavily relied on to express communication and to interpret others' communication and can replace or substitute verbal messages.

There are several reasons as to why non-verbal communication plays a vital role in communication:

- "Non-verbal communication is omnipresent."[74] They are included in every single communication act. To have total communication, all non-verbal channels such as the body, face, voice, appearance, touch, distance, timing, and other environmental forces must be engaged during face-to-face interaction. Written communication can also have non-verbal attributes. E-mails, web chats, and the social media have options to change text font colours, stationery, add emoticons, capitalization, and pictures in order to capture non-verbal cues into a verbal medium.[75]

- "Non-verbal behaviours are multifunctional."[76] Many different non-verbal channels are engaged at the same time in communication acts and allow the chance for simultaneous messages to be sent and received.

- "Non-verbal behaviours may form a universal language system."[76] Smiling, crying, pointing, caressing, and glaring are non-verbal behaviours that are used and understood by people regardless of nationality. Such non-verbal signals allow the most basic form of communication when verbal communication is not effective due to language barriers.

When verbal messages contradict non-verbal messages, observation of non-verbal behaviour is relied on to judge another's attitudes and feelings, rather than assuming the truth of the verbal message alone.[citation needed]

Non verbal communication can take the following forms:

- Paralinguistics are the elements other than language where the voice is involved in communication and includes tones, pitch, vocal cues etc. It also includes sounds from throat and all these are greatly influenced by cultural differences across borders.

- Proxemics deals with the concept of the space element in communication. Proxemics explains four zones of spaces, namely intimate, personal, social and public. This concept differs from culture to culture as the permissible space varies in different countries.

- Artifactics studies the non verbal signals or communication which emerges from personal accessories such as the dress or fashion accessories worn and it varies with culture as people of different countries follow different dress codes.

- Chronemics deals with the time aspects of communication and also includes the importance given to time. Some issues explaining this concept are pauses, silences and response lag during an interaction. This aspect of communication is also influenced by cultural differences as it is well known that there is a great difference in the value given by different cultures to time.

- Kinesics mainly deals with body language such as postures, gestures, head nods, leg movements, etc. In different countries, the same gestures and postures are used to convey different messages. Sometimes even a particular kinesic indicating something good in a country may have a negative meaning in another culture.[citation needed]

Interpersonal

Interpersonal communication refers to communication between distinct individuals. Its typical form is dyadic communication between two people but it can also refer to communication within groups.[77][78][32] It can be planned or unplanned and occurs in many different forms, like when greeting someone, during salary negotiations, or when making a phone call.[78][79] Some theorists understand interpersonal communication as a fuzzy concept that manifests in degrees.[80] On this view, an exchange is more or less interpersonal depending on how many people are present, whether it happens face-to-face rather than through telephone or email, and whether it focuses on the relationship between the communicators.[81][82] In this regard, group communication and mass communication are less typical forms of interpersonal communication and some theorists treat them as distinct types.[83][78][81]

Various theories of the function of interpersonal communication have been proposed. Some focus on how it helps people make sense of their world and create society while others hold that its primary purpose is to understand why other people act the way they do and to adjust one's behavior accordingly.[84] A closely related approach is to focus on information and see interpersonal communication as an attempt to reduce uncertainty about others and external events.[85] Other explanations understand it in terms of the needs it satisfies. This includes the needs of belonging somewhere, being included, being liked, maintaining relationships, and influencing the behavior of others.[85][86] On a practical level, interpersonal communication is used to coordinate one's actions with the actions of others in order to get things done.[87] Research on interpersonal communication concerns various topics, such as how people build, maintain, and dissolve relationships through communication, why they choose one message rather than another, what effects these messages have on the relationship and on the individual, and how to predict whether two people would like each other.[88]

Interpersonal communication can be synchronous or asynchronous. For asynchronous communication, the different parties take turns in sending and receiving messages. An example would be the exchange of letters or emails. For synchronous communication, both parties send messages at the same time.[77] This happens, for example, when one person is talking while the other person sends non-verbal messages in response signaling whether they agree with what is being said.[26] Some theorists distinguish between content messages and relational messages. Content messages express the speaker's feelings toward the topic of discussion. Relational messages, on the other hand, demonstrate the speaker's feelings toward their relationship with the other participants.[82]

Intrapersonal

Intrapersonal communication refers to communication with oneself.[89][79][90] In some cases this manifests externally, like when engaged in a monologue, taking notes, highlighting a passage, and writing a diary or a shopping list. But many forms of intrapersonal communication happen internally in the form of inner dialog, like when thinking about something or daydreaming.[89]

Intrapersonal communication serves various functions. As a form of inner dialog, it is usually triggered by external events and may happen in the form of articulating a phrase before expressing it externally, planning for the future, or as an attempt to process emotions when trying to calm oneself down in stressful situations.[78][32] It can help regulate one's own mental activity and outward behavior as well as internalize cultural norms and ways of thinking.[91] External forms of intrapersonal communication can aid one's memory, like when making a shopping list, help unravel difficult problems, as when solving a complex mathematical equation line by line, and internalize new knowledge, like when repeating new vocabulary to oneself.[92] Because of these functions, intrapersonal communication can be understood as "an exceptionally powerful and pervasive tool for thinking."[92]

Based on its role in self-regulation, some theorists have suggested that intrapersonal communication is more fundamental than interpersonal communication. This is based on the observation that young children sometimes use egocentric speech while playing in an attempt to direct their own behavior. On this view, interpersonal communication only develops later when the child moves from their early egocentric perspective to a more social perspective.[93][94] Other theorists contend that interpersonal communication is more basic. They explain this by arguing that language is used first by parents to regulate what their child does. Once the child has learned this, it can apply the same technique on itself to get more control over its own behavior.[91][95]

Contexts and purposes

There are countless other categorizations of communication besides the types discussed so far. They often focus on the context, purpose, and topic of communication. For example, organizational communication concerns communication between members of organizations such as corporations, nonprofits, or small businesses. Important in this regard is the coordination of the behavior of the different members as well as the interaction with customers and the general public.[96][97] Closely related terms are business communication, corporate communication, professional communication, and workspace communication.[98][99] Political communication refers to communication in relation to politics. It covers topics like electoral campaigns to influence the voters and legislative communication, like letters to a congress or committee documents. Specific emphasis is often given to propaganda and the role of mass media.[100] Intercultural communication is relevant to both organizational and political communication since they often involve attempts to exchange messages between communicators from different cultural backgrounds.[101] Important in this regard is to avoid misunderstandings since the cultural background affects how messages are formulated and interpreted.[54][55] This is also relevant for development communication, which is concerned with the use of communication for assisting in development, specifically concerning aid given by first-world countries to third-world countries.[102][103] Another important field is health communication, which is about communication in the field of healthcare and health promotion efforts. An important topic in this field is how healthcare providers, like doctors and nurses, should communicate with their patients.[104][105]

Many other types of communication are discussed in the academic literature. They include international communication, non-violent communication, strategic communication, military communication, aviation communication, risk communication, defensive communication, upward communication, interdepartmental communication, scientific communication, environmental communication, and agricultural communication.[106][107][108]

Non-human

Besides human communication, there are also many forms of non-human communication found, for example, in the animal kingdom and among plants. Sometimes, the term extrapersonal communication is used in this regard to contrast it with interpersonal and intrapersonal communication.[79] The field of inquiry studying non-human communication is called biosemiotics.[109] There are additional difficulties in this field for judging whether communication has taken place between two individuals. For example, acoustic signals are often easy to notice and analyze for scientists but additional difficulties come when judging whether tactile or chemical changes should be understood as communicative signals rather than as other biological processes.[110]

For this reason, researchers often use slightly altered definitions of communication in order to facilitate their work. A common assumption in this regard comes from evolutionary biology and holds that communication should somehow benefit the communicators in terms of natural selection.[111][112] In this regard, "communication can be defined as the exchange of information between individuals, wherein both the signaller and receiver may expect to benefit from the exchange."[113] So the sender should benefit by influencing the receiver's behavior and the receiver should benefit by responding to the signal. It is often held that these benefits should exist on average but not necessarily in every single case. This way, deceptive signaling can also be understood as a form of communication. One problem with the evolutionary approach is that it is often very difficult to assess the influence of such behavior on natural selection.[114] Another common pragmatic constraint is to hold that it is necessary to observe a response by the receiver following the signal when judging whether communication has occurred.[115]

Animals

Animal communication refers to the process of giving and taking information among animals.[116] The field studying animal communication is called zoosemiotics.[117] There are many parallels to human communication. For example, humans and many animals express sympathy by synchronizing their movements and postures.[118] Nonetheless, there are also important differences, like the fact that humans also engage in verbal communication while animal communication is restricted to non-verbal communication.[117][119] Some theorists have tried to distinguish human from animal communication based on the claim that animal communication lacks a referential function and is thus not able to refer to external phenomena. However, this view is often rejected, especially for higher animals.[120] A different approach is to draw the distinction based on the complexity of human language, especially its almost limitless ability to combine basic units of meaning into more complex meaning structures. For example, it has been argued that recursion is a property of human language that sets it apart from all non-human communicative systems.[121] Another difference is that human communication is frequently associated with a conscious intention to send information, which is often not discernable for animal communication.[122]

Animal communication can take a variety of forms, including visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory communication. Visual communication happens in the form of movements, gestures, facial expressions, and colors, like movements seen during mating rituals, the colors of birds, and the rhythmic light of fireflies. Auditory communication takes place through vocalizations by species like birds, primates, and dogs. It is frequently used to alert and warn. Lower animals often have very simple response patterns to auditory messages, reacting either by approach or avoidance.[123][117] More complex response patterns are observed for higher species, which may use different signals for different types of predators and responses. For example, certain primates use different signals for airborne and land predators.[124] Tactile communication occurs through touch, vibration, stroking, rubbing, and pressure. It is especially relevant for parent-young relations, courtship, social greetings, and defense. Olfactory and gustatory communication happens chemically through smells and tastes. [123][117]

There are huge differences between species concerning what functions communication plays, how much it is realized, and the behavior through which they communicate.[125] Common functions include the fields of courtship and mating, parent-offspring relations, social relations, navigation, self-defense, and territoriality.[126] An important part of courtship and mating consists in identifying and attracting potential mates. This can happen through songs, like grasshoppers and crickets, chemically through pheromones, like moths, and through visual messages by flashing light, like fireflies.[127][125] For many species, the offspring depends for its survival on the parent. One central function of parent-offspring communication is to recognize each other. In some cases, the parents are also able to guide the offspring's behavior.[128][129] Social animals, like chimpanzees, bonobos, wolves, and dogs, engage in various forms of communication to express their feelings and build relations.[130] Navigation concerns the movement through space in a purposeful manner, e.g. to locate food, avoid enemies, and follow a colleague. In bats, this happens through echolocation, i.e. by sending auditory signals and processing the information from the echoes. Bees are another often-discussed case in this respect since they perform a dance to indicate to other bees where flowers are located.[131] In regard to self-defense, communication is used to warn others and to assess whether a costly fight can be avoided.[132][133] Another function of communication is to mark and claim certain territories used for food and mating. For example, some male birds claim a hedge or part of a meadow by using songs to keep other males away and attract females.[134]

Two competing theories in the study of animal communication are nature theory and nurture theory. Their conflict concerns to what extent animal communication is programmed into the genes as a form of adaptation rather than learned from previous experience as a form of conditioning.[124][112] To the degree that it is learned, it usually happens through imprinting, i.e. as a form of learning that only happens in a certain phase and is then mostly irreversible.[135]

Plants and fungi

Communication is observed within the plant organism, i.e. within plant cells and between plant cells, between plants of the same or related species, and between plants and non-plant organisms, especially in the root zone. Plant roots communicate with rhizome bacteria, fungi, and insects within the soil. Recent research has shown that most of the microorganism plant communication processes are neuron-like.[136] Plants also communicate via volatiles when exposed to herbivory attack behavior, thus warning neighboring plants.[137] In parallel they produce other volatiles to attract parasites which attack these herbivores.

Fungi communicate to coordinate and organize their growth and development such as the formation of mycelia and fruiting bodies. Fungi communicate with their own and related species as well as with non fungal organisms in a great variety of symbiotic interactions, especially with bacteria, unicellular eukaryote, plants and insects through biochemicals of biotic origin. The biochemicals trigger the fungal organism to react in a specific manner, while if the same chemical molecules are not part of biotic messages, they do not trigger the fungal organism to react. This implies that fungal organisms can differentiate between molecules taking part in biotic messages and similar molecules being irrelevant in the situation. So far five different primary signalling molecules are known to coordinate different behavioral patterns such as filamentation, mating, growth, and pathogenicity. Behavioral coordination and production of signaling substances is achieved through interpretation processes that enables the organism to differ between self or non-self, a biotic indicator, biotic message from similar, related, or non-related species, and even filter out "noise", i.e. similar molecules without biotic content.[citation needed]

Pheromones are molecules released by one organism into the external environment to influence other individuals of the same species. Thus pheromone release is a form of communication. Pheromones promote sexual interaction (mating) in several fungal species. These include the aquatic fungus Allomyces macrogynus, the Mucorales fungus Mucor mucedo, Neurospora crassa and the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Rhodosporidium toruloides.[138][139][140]

Bacteria quorum sensing

Communication is not a tool used only by humans, plants and animals, but it is also used by microorganisms like bacteria. The process is called quorum sensing. Through quorum sensing, bacteria can sense the density of cells, and regulate gene expression accordingly. This can be seen in both gram positive and gram negative bacteria. This was first observed by Fuqua et al. in marine microorganisms like V. harveyi and V. fischeri.[141]

Natural bacterial transformation involves the transfer of naked DNA from one bacterium to another through the surrounding medium, and can be regarded as a relatively simple form of sexual interaction. In several bacterial species transformation is promoted by the production of an extracellular factor, termed a competence factor, that when released into the surrounding medium induces a state of competence in neighboring cells. The state of competence is the ability to take up the DNA released by another cell. Bacterial competence factors are similar to pheromones in multicellular organisms. Competence factors have been studied in Bacillus subtilis[142] and Streptococcus pneumoniae.[143]

Communication studies

Communication studies, also referred to as communication science, is the academic discipline studying communication. It is closely related to semiotics, with one difference being that communication studies focuses more on technical questions of how messages are sent, received, and processed while semiotics tackles more abstract questions in relation to meaning and hows signs acquire meaning.[124] Communication studies covers a wide area overlapping with many other disciplines, such as biology, anthropology, psychology, sociology, linguistics, media studies, and journalism.[144][145][146][147]

Many contributions in the field of communication studies focus on developing models and theories of communication. Models of communication aim to give a simplified overview of the main components involved in communication. Theories of communication, on the other hand, try to provide conceptual frameworks to accurately present communication in all its complexity.[144][27][148] Other topics in communication studies concern the function and effects of communication, like satisfying physiological and psychological needs and building relationships as well as gathering information about the environment, others, and oneself.[149][86] A further issue concerns the question of how communication systems change over time and how these changes correlate with other societal changes.[150] A related question focuses on psychological principles underlying those changes and the effects they have on how people exchange ideas.[151]

Communication was already studied as early as Ancient Greek. Important early theories are due to Plato and Aristotle, who gave a lot of emphasis on the role of public speaking. For example, Aristotle held that the goal of communication is to persuade the audience.[152] However, the field of communication studies only became a separate research discipline in the 20th century, especially starting in the 1940s.[153][154] The development of new communication technologies, such as telephone, radio, newspapers, television, and the internet, has had a big impact on communication and communication studies.[153][155][156] Today, communication studies is a wide discipline that includes many subfields dedicated to topics like interpersonal and intrapersonal communication, verbal and non-verbal communication, group communication, organizational communication, political communication, intercultural communication, mass communication, persuasive communication, and health communication.[153][106][157] Some works in communications studies try to provide a very general characterization of communication in the widest sense while others attempt to give a precise analysis of a specific form of communication.[106]

Barriers to effectiveness

Barriers to effective communication can distort the message or intention of the message being conveyed. This may result in failure of the communication process or cause an effect that is undesirable. These include filtering, selective perception, information overload, emotions, language, silence, communication apprehension, gender differences and political correctness.[158]

Noise

In any communication model, noise is interference with the decoding of messages sent over the channel by an encoder. To face communication noise, redundancy and acknowledgement must often be used. Acknowledgements are messages from the addressee informing the originator that his/her communication has been received and is understood.[159] Message repetition and feedback about message received are necessary in the presence of noise to reduce the probability of misunderstanding.

The act of disambiguation regards the attempt of reducing noise and wrong interpretations, when the semantic value or meaning of a sign can be subject to noise, or in presence of multiple meanings, which makes the sense-making difficult. Disambiguation attempts to decrease the likelihood of misunderstanding. This is also a fundamental skill in communication processes activated by counselors, psychotherapists, interpreters, and in coaching sessions based on colloquium. In Information Technology, the disambiguation process and the automatic disambiguation of meanings of words and sentences has also been an interest and concern since the earliest days of computer treatment of language.[160]

Cultural aspects

Cultural differences exist within countries (tribal/regional differences, dialects and so on), between religious groups and in organisations or at an organisational level – where companies, teams and units may have different expectations, norms and idiolects. Families and family groups may also experience the effect of cultural barriers to communication within and between different family members or groups. For example: words, colours and symbols have different meanings in different cultures. In most parts of the world, nodding your head means agreement, shaking your head means "no", but this is not true everywhere.[161]

Communication to a great extent is influenced by culture and cultural variables.[162][163][164][165] Understanding cultural aspects of communication refers to having knowledge of different cultures in order to communicate effectively with cross culture people. Cultural aspects of communication are of great relevance in today's world which is now a global village, thanks to globalisation. Cultural aspects of communication are the cultural differences which influence communication across borders. So in order to have an effective communication across the world it is desirable to have a knowledge of cultural variables effecting communication.

According to Michael Walsh and Ghil'ad Zuckermann, Western conversational interaction is typically "dyadic", between two particular people, where eye contact is important and the speaker controls the interaction; and "contained" in a relatively short, defined time frame. However, traditional Aboriginal conversational interaction is "communal", broadcast to many people, eye contact is not important, the listener controls the interaction; and "continuous", spread over a longer, indefinite time frame.[166][167]

See also

- 21st century skills

- Advice

- Augmentative and alternative communication

- Bias-free communication

- Communication rights

- Context as Other Minds

- Cross-cultural communication

- Data transmission

- Error detection and correction

- Human communication

- Information engineering

- Inter mirifica

- Intercultural communication

- Ishin-denshin

- Group dynamics

- Language

- Mass communication

- Proactive communications

- Sign system

- Signal

- Small talk

- SPEAKING

- Telepathy

- Understanding

- Writing

References

- ^ Cobley, Paul (2008-06-05), "Communication: Definitions and Concepts", in Donsbach, Wolfgang (ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. wbiecc071, doi:10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecc071, ISBN 978-1-4051-8640-7, archived from the original on 2021-12-07, retrieved 2021-07-20

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "communication". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ^ "What Is Communication?". 2012books.lardbucket.org. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- ^ Dance, Frank E. X. (1970-06-01). "The "Concept" of Communication". Journal of Communication. 20 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1970.tb00877.x. ISSN 0021-9916. Archived from the original on 2021-10-18. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Craig, Robert T. (1999). "Communication Theory as a Field". Communication Theory. 9 (2): 119–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1999.tb00355.x. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Peters, John Durham (1986). "Institutional Sources of Intellectual Poverty in Communication Research". Communication Research. 13 (4): 527–559. doi:10.1177/009365086013004002. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 145639228. Archived from the original on 2021-12-07. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Miller, Gerald R. (1966-06-01). "On Defining Communication: Another Stab". Journal of Communication. 16 (2): 88–98. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1966.tb00020.x. ISSN 0021-9916. PMID 5941548. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Fiske, John (1982): Introduction to Communication Studies. London: Routledge

- ^ Chandler, Daniel (18 September 1995). "The Transmission Model of Communication". Archived from the original on 2021-05-06.

- ^ Shannon, Claude E. & Warren Weaver (1949). A Mathematical Model of Communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press

- ^ a b Publishers, HarperCollins. "communication". www.ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "communication". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "communication". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Rosengren, Karl Erik (11 February 2000). "1.1 On communication". Communication: An Introduction. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-8039-7837-9.

- ^ a b Munodawafa, D. (1 June 2008). "Communication: concepts, practice and challenges". Health Education Research. 23 (3): 369–370. doi:10.1093/her/cyn024. PMID 18504296.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (1996). "Meaning and communication". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dance, Frank E. X. (1 June 1970). "The "Concept" of Communication". Journal of Communication. 20 (2): 201–210. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1970.tb00877.x.

- ^ a b c Gordon, George N. "communication". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Blackburn, Simon (1996). "Intention and communication". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge.

- ^ Nöth, Winfried (1995). Handbook of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-253-20959-7.

- ^ Luhmann, Niklas (August 1992). "What is Communication?". Communication Theory. 2 (3): 251–259. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.1992.tb00042.x.

- ^ Peters, John Durham (1999). Speaking into the air : a history of the idea of communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-226-66276-4. OCLC 40452957. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Ruben, Brent D. (2001). "Models Of Communication". Encyclopedia of Communication and Information.

- ^ a b c d McQuail, Denis (2008). "Models of communication". In Donsbach, Wolfgang (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Communication, 12 Volume Set. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-13199-5.

- ^ a b Narula, Uma (2006). "1. Basic Communication Models". Handbook of Communication Models, Perspectives, Strategies. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0513-3.

- ^ a b c d e "1.2 The Communication Process". Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 29 September 2016. ISBN 9781946135070.

- ^ a b Cobley, Paul; Schulz, Peter J. (30 January 2013). "Introduction". Theories and Models of Communication. De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110240450. ISBN 978-3-11-024045-0.

- ^ a b Fiske, John (2011). "2. Other models". Introduction to Communication Studies. Routledge.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). "transmission models". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8.

- ^ a b Kastberg, Peter (13 December 2019). Knowledge Communication: Contours of a Research Agenda. Frank & Timme GmbH. p. 56. ISBN 978-3-7329-0432-7.

- ^ a b c d Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (18 August 2009). Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. SAGE Publications. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4129-5937-7.

- ^ a b c Barnlund, Dean C. (1970). "A Transactional Model of Communication". In Sereno, Kenneth K.; Mortensen, C. David (eds.). Foundations of Communication Theory. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-044623-9.

- ^ Watson, James; Hill, Anne (16 February 2012). "Lasswell's model of communication". Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84966-563-6.

- ^ Wenxiu, Peng (2015-09-01). "Analysis of New Media Communication Based on Lasswell's "5W" Model". Journal of Educational and Social Research. doi:10.5901/jesr.2015.v5n3p245. ISSN 2239-978X. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Steinberg, Sheila (2007). An Introduction to Communication Studies. Juta and Company Ltd. pp. 52–3. ISBN 978-0-7021-7261-8.

- ^ Tengan, Callistus; Aigbavboa, Clinton; Thwala, Wellington Didibhuku (27 April 2021). Construction Project Monitoring and Evaluation: An Integrated Approach. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-000-38141-2.

- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa (5 July 1995). Essentials of Mass Communication Theory. SAGE. pp. 12–3. ISBN 978-0-8039-7357-2.

- ^ Sapienza, Zachary S.; Iyer, Narayanan; Veenstra, Aaron S. (3 September 2015). "Reading Lasswell's Model of Communication Backward: Three Scholarly Misconceptions". Mass Communication and Society. 18 (5): 599–622. doi:10.1080/15205436.2015.1063666. S2CID 146389958.

- ^ Feicheng, Ma (31 May 2022). Information Communication. Springer Nature. p. 24. ISBN 978-3-031-02293-7.

- ^ Braddock, Richard (1958). "An Extension of the "Lasswell Formula"". Journal of Communication. 8 (2): 88–93. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1958.tb01138.x.

- ^ a b Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). "Shannon and Weaver's model". A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956875-8.

- ^ Li, Hong Ling (September 2007). "From Shannon-Weaver to Boisot: A Review on the Research of Knowledge Transfer Model". 2007 International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing: 5439–5442. doi:10.1109/WICOM.2007.1332. ISBN 978-1-4244-1311-9. S2CID 15690224.

- ^ a b Fiske, John (2011). "1. Communication theory". Introduction to Communication Studies. Routledge.

- ^ Shannon, C. E. (July 1948). "A Mathematical Theory of Communication". Bell System Technical Journal. 27 (3): 379–423. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x.

- ^ Weaver, Warren (1 September 1998). "Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication". The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-72546-3.

- ^ Januszewski, Alan (2001). Educational Technology: The Development of a Concept. Libraries Unlimited. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-56308-749-3.

- ^ Watson, James; Hill, Anne (16 February 2012). "Gerbner's model of communication". Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies. A&C Black. pp. 112–3. ISBN 9781849665636.

- ^ Melkote, Srinivas R.; Steeves, H. Leslie (14 December 2001). Communication for Development in the Third World: Theory and Practice for Empowerment. SAGE Publications. p. 108. ISBN 9780761994763.

- ^ Straubhaar, Joseph; LaRose, Robert; Davenport, Lucinda (1 January 2015). Media Now: Understanding Media, Culture, and Technology. Cengage Learning. pp. 18–9. ISBN 9781305533851.

- ^ Steinberg, S. (1995). Introduction to Communication Course Book 1: The Basics. Juta and Company Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7021-3649-8.

- ^ Bowman, J. P.; Targowski, A. S. (1 October 1987). "Modeling the Communication Process: The Map is Not the Territory". Journal of Business Communication. 24 (4): 21–34. doi:10.1177/002194368702400402.

- ^ a b Moore, David Mike (1994). Visual Literacy: A Spectrum of Visual Learning. Educational Technology. pp. 90–1. ISBN 978-0-87778-264-3.

- ^ a b c Schramm, Wilbur (1954). "How communication works". The Process and Effects of Mass Communication. University of Illinois Press.

- ^ a b Blythe, Jim (5 March 2009). Key Concepts in Marketing. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-84787-498-6. Cite error: The named reference "Blythe2009" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Meng, Xiangfei (12 March 2020). National Image: China's Communication of Cultural Symbols. Springer Nature. p. 120. ISBN 978-981-15-3147-7. Cite error: The named reference "Meng2020" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 48.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 47.

- ^ a b Watson, James; Hill, Anne (22 October 2015). Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 20–22. ISBN 9781628921496.

- ^ Lawson, Celeste; Gill, Robert; Feekery, Angela; Witsel, Mieke (12 June 2019). Communication Skills for Business Professionals. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–7. ISBN 9781108594417.

- ^ Dwyer, Judith (15 October 2012). Communication for Business and the Professions: Strategie s and Skills. Pearson Higher Education AU. p. 12. ISBN 9781442550551.

- ^ Barnlund 2013, p. 57-60.

- ^ Chandler 2011, p. 58.

- ^ Burton, Graeme; Dimbleby, Richard (4 January 2002). Teaching Communication. Routledge. p. 126. ISBN 9781134970452.

- ^ Beynon-Davies, P. (30 November 2010). Significance: Exploring the Nature of Information, Systems and Technology. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 52. ISBN 9780230295025.

- ^ Ferguson, Sherry Devereaux; Lennox-Terrion, Jenepher; Ahmed, Rukhsana; Jaya, Peruvemba (2014). Communication in Everyday Life: Personal and Professional Contexts. Canada: Oxford University Press. p. 464. ISBN 9780195449280. Archived from the original on 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- ^ Xin Li. "Complexity Theory – the Holy Grail of 21st Century". Lane Dept of CSEE, West Virginia University. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15.

- ^ Bateson, Gregory (1960). Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

- ^ AIIM. "What is Collaboration?". www.aiim.org. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ "What is Collaboration?". aiim. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Communication Skills: Definitions and Examples | Indeed.com India". In.indeed.com. Archived from the original on 2022-07-22. Retrieved 2022-07-24.

- ^ "Written Communication: Characteristics and Importance (Advantages and Limitations)". Your article library. 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Types of Body Language". Simplybodylanguage.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ Wazlawick, Paul (1970's) opus

- ^ (Burgoon, J., Guerrero, L., Floyd, K., (2010). Nonverbal Communication, Taylor & Francis. p. 3 )

- ^ Martin-Rubió, Xavier (2018-09-30). Contextualising English as a Lingua Franca: From Data to Insights. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-1696-0. Archived from the original on 2021-02-04. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ a b (Burgoon et al., p. 4)

- ^ a b Chandler 2011, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Minnesota2016awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Ezhilarasu, Punitha (1 January 2016). Educational Technology: Integrating Innovations in Nursing Education. Wolters Kluwer. p. 178. ISBN 9789351297222.

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 547. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 547-8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Trenholm, Sarah; Jensen, Arthur (2013). Interpersonal Communication Seventh Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 360–361.

- ^ Danesi 2013, p. 168.

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 548-9. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 549. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Gamble, Teri Kwal; Gamble, Michael W. (2 January 2019). The Interpersonal Communication Playbook. SAGE Publications. pp. 14–6. ISBN 9781544332796.

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 546. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 546-7. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Chandler 2011, p. 225.

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 566. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 567-8. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ a b Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 568-9. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ Littlejohn & Foss 2009, p. 567. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLittlejohnFoss2009 (help)

- ^ Anderson, James A. (23 May 2012). Communication Yearbook 11. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 9781135148447.

- ^ Vocate, Donna R. (6 December 2012). Intrapersonal Communication: Different Voices, Different Minds. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781136601842.

- ^ Zink, Julie (2017). "1: Introducing Organizational Communication". Organizational Communication. Granite State Collage.

- ^ Putnam, Linda; Woo, DaJung; Banghart, Scott. "Organizational Communication". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Hartley, Peter; Bruckmann, Clive (28 January 2008). Business Communication. Routledge. ISBN 9781134645725.

- ^ Mullany, Louise (11 June 2020). Professional Communication: Consultancy, Advocacy, Activism. Springer Nature. p. 2. ISBN 9783030416683.

- ^ Darity, William A. (2008). "Communication, Political". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028659664.

- ^ Gale, Thomson (17 October 2006). "Intercultural communication". Encyclopedia of Small Business. Thomson Gale. ISBN 9780787691127.

- ^ Mody, Bella (29 April 2003). International and Development Communication: A 21st-Century Perspective. SAGE. p. 129. ISBN 9780761929017.

- ^ Steinberg 2007, p. 301. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSteinberg2007 (help)

- ^ Steinberg 2007, p. 307. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSteinberg2007 (help)

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 395.

- ^ a b c Steinberg 2007, p. 286. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSteinberg2007 (help)

- ^ Bickford, David; Posa, Mary Rose C.; Qie, Lan; Campos-Arceiz, Ahimsa; Kudavidanage, Enoka P. (July 2012). "Science communication for biodiversity conservation". Biological Conservation. 151 (1): 74–76. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.016.

- ^ Nothhaft, Howard; Werder, Kelly Page; Verčič, Dejan; Zerfass, Ansgar (21 May 2020). Future Directions of Strategic Communication. Routledge. p. 236. ISBN 9781000468250.

- ^ Emmeche, Claus (2003). Huyssteen, Jacobus Wentzel Van (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. Macmillan Reference. pp. 63–4. ISBN 9780028657042.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Baluška & Ninkovic 2010, p. 1, 3.

- ^ a b Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Baluška & Ninkovic 2010, p. 128.

- ^ Baluška & Ninkovic 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Baluška & Ninkovic 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 25-6.

- ^ a b c d Chandler 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 107.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 5.

- ^ a b Schement 2002, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Danesi, Marcel (2000). Encyclopedic dictionary of semiotics, media, and communications. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 58–9. ISBN 9780802047830.

- ^ a b Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 26-9.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 26-7.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 19-20.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 27-8.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 28.

- ^ Baluška & Ninkovic 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 28-9.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 14-5.

- ^ Baluska, F.; Marcuso, Stefano; Volkmann, Dieter (2006). Communication in plants: neuronal aspects of plant life. Taylor & Francis US. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-540-28475-8. Archived from the original on 2016-05-12. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

...the emergence of plant neurobiology as the most recent area of plant sciences.

- ^ Ian T. Baldwin; Jack C. Schultz (1983). "Rapid Changes in Tree Leaf Chemistry Induced by Damage: Evidence for Communication Between Plants". Science. 221 (4607): 277–279. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..277B. doi:10.1126/science.221.4607.277. PMID 17815197. S2CID 31818182.

- ^ O'Day, D.H. (1981). Modes of cellular communicatin and sexual interactions in eukaryotic microbes. In: Sexual Interactions in Eukaryotic Microbes. (O'Day, D.H. & Horgen, P.A., eds), pp. 3-17. New York: Academic Press

- ^ Davey, J. (March 1992). "Mating pheromones of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe: purification and structural characterization of M-factor and isolation and analysis of two genes encoding the pheromone". The EMBO Journal. 11 (3): 951–960. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05134.x. PMC 556536. PMID 1547790.

- ^ Akada, Rinji; Minomi, Kenjiro; Kai, Jingo; Yamashita, Ichiro; Miyakawa, Tokichi; Fukui, Sakuzo (August 1989). "Multiple genes coding for precursors of rhodotorucine A, a farnesyl peptide mating pheromone of the basidiomycetous yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 9 (8): 3491–3498. doi:10.1128/mcb.9.8.3491-3498.1989. PMC 362396. PMID 2571924.

- ^ Anand, Sandhya. Quorum Sensing- Communication Plan For Microbes Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. Article dated 2010-12-28, retrieved on 2012-04-03.

- ^ Akrigg, A.; Ayad, S. R. (1970-04-01). "Studies on the competence-inducing factor of Bacillus subtilis". Biochemical Journal. 117 (2): 397–403. doi:10.1042/bj1170397. PMC 1178873. PMID 4986873.

- ^ Håvarstein, L S; Coomaraswamy, G; Morrison, D A (1995-11-21). "An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 92 (24): 11140–11144. Bibcode:1995PNAS...9211140H. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.24.11140. PMC 40587. PMID 7479953.

- ^ a b Danesi 2013, p. 181.

- ^ Håkansson & Westander 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Gill, David; Adams, Bridget (1998). ABC of Communication Studies. Nelson Thornes. p. vii. ISBN 9780174387435.

- ^ Berger, Charles R.; Roloff, Michael E.; Ewoldsen, David R. (2010). The Handbook of Communication Science. SAGE Publications. p. 10. ISBN 9781412918138.

- ^ Steinberg 2007, p. 18. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSteinberg2007 (help)

- ^ Danesi 2013, p. 184.

- ^ Danesi 2013, p. 184-5.

- ^ Schement 2002, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Schement 2002, p. 155-6.

- ^ Berger, Charles R.; Roloff, Michael E.; Ewoldsen, David R. (2010). The Handbook of Communication Science. SAGE Publications. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9781412918138.

- ^ Steinberg 2007, p. 3. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSteinberg2007 (help)

- ^ Beck, Andrew; Bennett, Peter; Wall, Peter (2002). Communication Studies: The Essential Introduction. Psychology Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780415247511.

- ^ Beck, Andrew; Bennett, Peter; Wall, Peter (2002). Communication Studies: The Essential Introduction. Psychology Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780415247511.

- ^ Robbins, S., Judge, T., Millett, B., & Boyle, M. (2011). Organisational Behaviour. 6th ed. Pearson, French's Forest, NSW pp. 315–317.

- ^ North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO Standardization Agency AAP-6 – Glossary of terms and definitions, p. 43.

- ^ Nancy Ide, Jean Véronis. "Word Sense Disambiguation: The State of the Art", Computational Linguistics, 24(1), 1998, pp. 1–40.

- ^ Nageshwar Rao, Rajendra P. Das, Communication skills, Himalaya Publishing House, 9789350516669, p. 48

- ^ "The Communication and Cognitive Components of Culture". Archived from the original on 2013-07-18. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- ^ "Incorrect Link to Beyond Intractability Essay". Beyond Intractability. 2017-04-18. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ "Important Components of Cross-Cultural Communication Essay". Studymode.com. Archived from the original on 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ "Portable Document Format (PDF)". Ijdesign.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-14. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad; et al. (2015), Engaging – A Guide to Interacting Respectfully and Reciprocally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, and their Arts Practices and Intellectual Property (PDF), Australian Government: Indigenous Culture Support, p. 12, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2016, retrieved 25 June 2016

- ^ Walsh, Michael (1997), Cross cultural communication problems in Aboriginal Australia, Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit, pp. 7–9, ISBN 9780731528745, archived from the original on 13 August 2016, retrieved 25 June 2016

Works cited

- Barnlund, Dean C. (5 July 2013). "A Transactional Model of Communication". In Akin, Johnnye; Goldberg, Alvin; Myers, Gail; Stewart, Joseph (eds.). Language Behavior. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 43–61. ISBN 9783110878752.

- Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199568758.

- Danesi, Marcel (1 January 2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Semiotics, Media, and Communications. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802083296.

- Danesi, Marcel (17 June 2013). Encyclopedia of Media and Communication. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442695535.

- Littlejohn, Stephen W.; Foss, Karen A. (18 August 2009). Encyclopedia of Communication Theory. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412959377.

- Schement, Jorge Reina (2002). Encyclopedia of Communication and Information. Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028653853.

- Håkansson, Gisela; Westander, Jennie (2013). Communication in Humans and Other Animals. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027204585.

- Baluška, František; Ninkovic, Velemir (5 August 2010). Plant Communication from an Ecological Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783642121623.

- Berea, Anamaria (16 December 2017). Emergence of Communication in Socio-Biological Networks. Springer. ISBN 9783319645650.

- Steinberg, Sheila (2007). An Introduction to Communication Studies. Juta and Company Ltd. ISBN 9780702172618.

Further reading

- Fogel, A., Nwokah, E., Dedo, J.Y., Messinger, D., Dickson, K.L., Matusov, E. and Holt, S.A., 1992. Social process theory of emotion: A dynamic systems approach. Social Development, 1(2), pp.122-142.

- Innis, Harold; Innis, Mary Q. (1975) [1950]. Empire and Communications. Foreword by Marshall McLuhan (Revised ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6119-5. OCLC 19403451.

External links

Quotations related to Communication at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Communication at Wikiquote Media related to Communication at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Communication at Wikimedia Commons