Terraforming: Difference between revisions

SpaceHist65 (talk | contribs) m fixed missing page number (#6) |

Ebhughes20 (talk | contribs) Edited the "habitability requirements" section with more specific information, sub-sections (divided by each of the specific requirements), and information about the application of the term habitability to the concept terraforming. A new figure is added as well. |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

Fogg suggests that [[Mars]] was a biologically compatible planet in its youth, but is not now in any of these three categories, because it can only be terraformed with greater difficulty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Terraforming : engineering planetary environments|last=Fogg|first=Martyn J.|date=1995|publisher=Society of Automotive Engineers|isbn=1560916095|oclc=32348444}}</ref> |

Fogg suggests that [[Mars]] was a biologically compatible planet in its youth, but is not now in any of these three categories, because it can only be terraformed with greater difficulty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Terraforming : engineering planetary environments|last=Fogg|first=Martyn J.|date=1995|publisher=Society of Automotive Engineers|isbn=1560916095|oclc=32348444}}</ref> |

||

==Habitability |

== Terraforming: Habitability Requirements == |

||

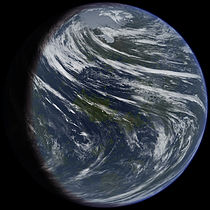

[[File:Habitability Requirements.png|thumb|300x300px|Necessary conditions for habitability, adapted from <ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hoehler |first=Tori M. |date=2007-12-28 |title=An Energy Balance Concept for Habitability |url=http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ast.2006.0095 |journal=Astrobiology |language=en |volume=7 |issue=6 |pages=824–838 |doi=10.1089/ast.2006.0095 |issn=1531-1074}}</ref>]] |

|||

{{main|Planetary habitability}} |

|||

| ⚫ | Planetary habitability, broadly defined as the capacity for an astronomical body to sustain life, requires that various [[Geophysics|geophysical]], [[Geochemistry|geochemical]], and [[Astrophysics|astrophysical]] criteria must be met before the surface of such a body is considered habitable. Modifying a planetary surface such that it is able to sustain life, particularly for humans, is generally the end-goal of the hypothetical process of terraforming. Of particular interest in the context of terraforming is the set of factors that have sustained complex, [[Multicellular organism|multicellular]] animals in addition to simpler organisms on Earth. Research and theory in this regard is a component of [[planetary science]] and the emerging discipline of [[astrobiology]]. |

||

{{More citations needed|section|date=December 2022}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Classifications of the criteria of habitability can be varied, but it is generally agreed upon that the presence of water, non-extreme temperatures, and an energy source put broad constraints on habitability<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal |last=Lineweaver |first=Charles H. |last2=Chopra |first2=Aditya |date=2012-05-30 |title=The Habitability of Our Earth and Other Earths: Astrophysical, Geochemical, Geophysical, and Biological Limits on Planet Habitability |url=https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105531 |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |language=en |volume=40 |issue=1 |pages=597–623 |doi=10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105531 |issn=0084-6597}}</ref>. Other requirements for habitability have been defined as the presence of raw materials, an energy source, a solvent, and clement conditions<ref name=":10">{{Citation |last=Hoehler |first=Tori M. |title=Life’s Requirements |date=2018 |url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-30648-3_74-1 |work=Handbook of Exoplanets |pages=1–22 |editor-last=Deeg |editor-first=Hans J. |access-date=2023-03-14 |place=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-30648-3_74-1 |isbn=978-3-319-30648-3 |last2=Som |first2=Sanjoy M. |last3=Kiang |first3=Nancy Y. |editor2-last=Belmonte |editor2-first=Juan Antonio}}</ref>, or [[CHON|elemental requirements]] (such as carbon, hydrogen nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous and sulfur), an energy source, water, and reasonable physiochemical conditions<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last=Cockell |first=C.S. |last2=Bush |first2=T. |last3=Bryce |first3=C. |last4=Direito |first4=S. |last5=Fox-Powell |first5=M. |last6=Harrison |first6=J.P. |last7=Lammer |first7=H. |last8=Landenmark |first8=H. |last9=Martin-Torres |first9=J. |last10=Nicholson |first10=N. |last11=Noack |first11=L. |last12=O'Malley-James |first12=J. |last13=Payler |first13=S.J. |last14=Rushby |first14=A. |last15=Samuels |first15=T. |date=2016-01-20 |title=Habitability: A Review |url=http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ast.2015.1295 |journal=Astrobiology |language=en |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=89–117 |doi=10.1089/ast.2015.1295 |issn=1531-1074}}</ref>. When applied to organisms present on the earth, including humans, these constraints can substantially narrow. |

|||

| ⚫ | In its astrobiology roadmap, [[NASA]] has defined the principal habitability criteria as "extended regions of liquid water, conditions favorable for the assembly of complex [[ |

||

| ⚫ | In its astrobiology roadmap, [[NASA]] has defined the principal habitability criteria as "extended regions of liquid water, conditions favorable for the assembly of complex [[Organic molecule|organic molecules]], and energy sources to sustain [[metabolism]]."<ref>{{Cite web |date=2011-01-17 |title=Astrobiology Roadmap |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110117011137/http://astrobiology.arc.nasa.gov/roadmap/g1.html |access-date=2023-03-17 |website=web.archive.org}}</ref> |

||

=== Temperature Requirements === |

|||

The general temperature range for all life on earth is -20ºC to 122ºC<ref name=":8" />; this may constitute a bounding range for the development of life on other planets, in the context of terraforming. Much of earth's biomass (~60%) relies on [[photosynthesis]] for an energy source, while a further ~40% is [[Chemotroph|chemotropic]]<ref name=":8" />. For the development of life on other planetary bodies, chemical energy may have been critical<ref name=":8" />, while for sustaining life on another planetary body in our solar system, sufficiently high solar energy may also be necessary for phototrophic organisms. |

|||

=== Water Requirements === |

|||

All known life requires water<ref name=":10" />; thus the capacity for planetary body to sustain water is a critical aspect of habitability. The "[[Circumstellar habitable zone|Habitable Zone]]" of a solar system is generally defined as the region in which stable surface liquid water may be present on a planetary body<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" />. The boundaries of the Habitable Zone were originally defined by water loss by [[photolysis]] and hydrogen escape, setting a limit on how close a planet may be to its orbited star, and the prevalence of CO<sub>2</sub> clouds that would increase [[albedo]], setting an outer boundary on stable liquid water<ref name=":11">{{Cite journal |last=Kasting |first=James F. |last2=Whitmire |first2=Daniel P. |last3=Reynolds |first3=Ray T. |date=1993-01-01 |title=Habitable Zones around Main Sequence Stars |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103583710109 |journal=Icarus |language=en |volume=101 |issue=1 |pages=108–128 |doi=10.1006/icar.1993.1010 |issn=0019-1035}}</ref>. These constraints are applicable in particular to Earth-like planets and would not as easily apply to icy moons like [[Europa (moon)|Europa]] and [[Enceladus]]. |

|||

=== Energy Requirements === |

|||

On the most fundamental level, the only absolute requirement of life may be thermodynamic [[Non-equilibrium thermodynamics|disequilibrium]], or the presence of [[Gibbs free energy|Gibbs Free Energy]]<ref name=":10" />. It has been argued that habitability can be conceived of as a balance between life's demand for energy and the capacity for the environment to provide such energy<ref name=":10" />. For humans, energy comes in the form of sugars, fats, and proteins provided by consuming plants and animals, necessitating in turn that a habitable planet for humans can sustain such organisms<ref>{{Cite web |title=Cell Energy, Cell Functions {{!}} Learn Science at Scitable |url=https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/cell-energy-and-cell-functions-14024533/ |access-date=2023-04-13 |website=www.nature.com |language=en}}</ref>. |

|||

=== Elemental Requirements === |

|||

On earth, life generally requires six elements in high abundance: [[carbon]], [[hydrogen]], [[nitrogen]], [[oxygen]], [[Phosphorus cycle|phosphorous]], and [[sulfur]]<ref name=":9" />. These elements are considered "essential" for all known life and plentiful within biological systems<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Wackett |first=Lawrence |last2=Dodge |first2=Anthony |last3=Ellis |first3=Lynda |date=2004-02-01 |title=Microbial Genomics and the Periodic Table |url=https://journals.asm.org/doi/epub/10.1128/AEM.70.2.647-655.2004 |journal=Applied and Environmental Microbiology |volume=70 |issue=2}}</ref>. Additional elements crucial to life include the cations Mg<sup>2+</sup>, Ca<sup>2+</sup>, K<sup>+</sup> and Na<sup>+</sup> and the anion Cl<sup>-</sup><ref name=":0" />. Many of these elements may undergo biologically facilitated oxidation or reduction to produce usable metabolic energy<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Falkowski |first=Paul G. |last2=Fenchel |first2=Tom |last3=Delong |first3=Edward F. |date=2008-05-23 |title=The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth's Biogeochemical Cycles |url=https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1153213 |journal=Science |language=en |volume=320 |issue=5879 |pages=1034–1039 |doi=10.1126/science.1153213 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref>. |

|||

==Preliminary stages== |

==Preliminary stages== |

||

Revision as of 16:16, 13 April 2023

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2020) |

Terraforming or terraformation ("Earth-shaping") is the hypothetical process of deliberately modifying the atmosphere, temperature, surface topography or ecology of a planet, moon, or other body to be similar to the environment of Earth to make it habitable for humans to live on.

The concept of terraforming developed from both science fiction and actual science. Carl Sagan, an astronomer, proposed the planetary engineering of Venus in 1961, which is considered one of the first accounts of the concept.[1] The term was coined by Jack Williamson in a science-fiction short story ("Collision Orbit") published in 1942 in Astounding Science Fiction,[2] although terraforming in popular culture may predate this work.

Even if the environment of a planet could be altered deliberately, the feasibility of creating an unconstrained planetary environment that mimics Earth on another planet has yet to be verified. While Venus, Earth, Mars, and even the Moon have been studied in relation to the subject, Mars is usually considered to be the most likely candidate for terraforming. Much study has been done concerning the possibility of heating the planet and altering its atmosphere, and NASA has even hosted debates on the subject. Several potential methods for the terraforming of Mars may be within humanity's technological capabilities, but according to Martin Beech, the economic attitude of preferring short-term profits over long-term investments will not support a terraforming project.[3]

The long timescales and practicality of terraforming are also the subject of debate. As the subject has gained traction, research has expanded to other possibilities including biological terraforming, para-terraforming, and modifying humans to better suit the environments of planets and moons. Despite this, questions still remain in areas relating to the ethics, logistics, economics, politics, and methodology of altering the environment of an extraterrestrial world, presenting issues to the implementation of the concept.

History of scholarly study

The astronomer Carl Sagan proposed the planetary engineering of Venus in an article published in the journal Science in 1961.[1] Sagan imagined seeding the atmosphere of Venus with algae, which would convert water, nitrogen and carbon dioxide into organic compounds. As this process removed carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the greenhouse effect would be reduced until surface temperatures dropped to "comfortable" levels. The resulting carbon, Sagan supposed, would be incinerated by the high surface temperatures of Venus, and thus be sequestered in the form of "graphite or some involatile form of carbon" on the planet's surface.[4] However, later discoveries about the conditions on Venus made this particular approach impossible. One problem is that the clouds of Venus are composed of a highly concentrated sulfuric acid solution. Even if atmospheric algae could thrive in the hostile environment of Venus's upper atmosphere, an even more insurmountable problem is that its atmosphere is simply far too thick—the high atmospheric pressure would result in an "atmosphere of nearly pure molecular oxygen" and cause the planet's surface to be thickly covered in fine graphite powder.[4] This volatile combination could not be sustained through time. Any carbon that was fixed in organic form would be liberated as carbon dioxide again through combustion, "short-circuiting" the terraforming process.[4]

Sagan also visualized making Mars habitable for human life in "Planetary Engineering on Mars" (1973), an article published in the journal Icarus.[5] Three years later, NASA addressed the issue of planetary engineering officially in a study, but used the term "planetary ecosynthesis" instead.[6] The study concluded that it was possible for Mars to support life and be made into a habitable planet. The first conference session on terraforming, then referred to as "Planetary Modeling", was organized that same year.

In March 1979, NASA engineer and author James Oberg organized the First Terraforming Colloquium, a special session at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston. Oberg popularized the terraforming concepts discussed at the colloquium to the general public in his book New Earths (1981).[7] Not until 1982 was the word terraforming used in the title of a published journal article. Planetologist Christopher McKay wrote "Terraforming Mars", a paper for the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society.[8] The paper discussed the prospects of a self-regulating Martian biosphere, and the word "terraforming" has since become the preferred term.[citation needed] In 1984, James Lovelock and Michael Allaby published The Greening of Mars.[9] Lovelock's book was one of the first to describe a novel method of warming Mars, where chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are added to the atmosphere.

Motivated by Lovelock's book, biophysicist Robert Haynes worked behind the scenes[citation needed] to promote terraforming, and contributed the neologism Ecopoiesis,[10] forming the word from the Greek οἶκος, oikos, "house",[11] and ποίησις, poiesis, "production".[12] Ecopoiesis refers to the origin of an ecosystem. In the context of space exploration, Haynes describes ecopoiesis as the "fabrication of a sustainable ecosystem on a currently lifeless, sterile planet". Fogg defines ecopoiesis as a type of planetary engineering and is one of the first stages of terraformation. This primary stage of ecosystem creation is usually restricted to the initial seeding of microbial life.[13] A 2019 opinion piece by Lopez, Peixoto and Rosado has reintroduced microbiology as a necessary component of any possible colonization strategy based on the principles of microbial symbiosis and their beneficial ecosystem services.[14] As conditions approach that of Earth, plant life could be brought in, and this will accelerate the production of oxygen, theoretically making the planet eventually able to support animal life.

Aspects and definitions

In 1985, Martyn J. Fogg started publishing several articles on terraforming. He also served as editor for a full issue on terraforming for the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society in 1992. In his book Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments (1995), Fogg proposed the following definitions for different aspects related to terraforming:[13]

- Planetary engineering: the application of technology for the purpose of influencing the global properties of a planet.

- Geoengineering: planetary engineering applied specifically to Earth. It includes only those macro engineering concepts that deal with the alteration of some global parameter, such as the greenhouse effect, atmospheric composition, insolation or impact flux.

- Terraforming: a process of planetary engineering, specifically directed at enhancing the capacity of an extraterrestrial planetary environment to support life as we know it. The ultimate achievement in terraforming would be to create an open planetary ecosystem emulating all the functions of the biosphere of Earth, one that would be fully habitable for human beings.

Fogg also devised definitions for candidate planets of varying degrees of human compatibility:[15]

- Habitable Planet (HP): A world with an environment sufficiently similar to Earth's as to allow comfortable and free human habitation.

- Biocompatible Planet (BP): A planet possessing the necessary physical parameters for life to flourish on its surface. If initially lifeless, then such a world could host a biosphere of considerable complexity without the need for terraforming.

- Easily Terraformable Planet (ETP): A planet that might be rendered biocompatible, or possibly habitable, and maintained so by modest planetary engineering techniques and with the limited resources of a starship or robot precursor mission.

Fogg suggests that Mars was a biologically compatible planet in its youth, but is not now in any of these three categories, because it can only be terraformed with greater difficulty.[16]

Terraforming: Habitability Requirements

Planetary habitability, broadly defined as the capacity for an astronomical body to sustain life, requires that various geophysical, geochemical, and astrophysical criteria must be met before the surface of such a body is considered habitable. Modifying a planetary surface such that it is able to sustain life, particularly for humans, is generally the end-goal of the hypothetical process of terraforming. Of particular interest in the context of terraforming is the set of factors that have sustained complex, multicellular animals in addition to simpler organisms on Earth. Research and theory in this regard is a component of planetary science and the emerging discipline of astrobiology.

Classifications of the criteria of habitability can be varied, but it is generally agreed upon that the presence of water, non-extreme temperatures, and an energy source put broad constraints on habitability[18]. Other requirements for habitability have been defined as the presence of raw materials, an energy source, a solvent, and clement conditions[19], or elemental requirements (such as carbon, hydrogen nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous and sulfur), an energy source, water, and reasonable physiochemical conditions[20]. When applied to organisms present on the earth, including humans, these constraints can substantially narrow.

In its astrobiology roadmap, NASA has defined the principal habitability criteria as "extended regions of liquid water, conditions favorable for the assembly of complex organic molecules, and energy sources to sustain metabolism."[21]

Temperature Requirements

The general temperature range for all life on earth is -20ºC to 122ºC[18]; this may constitute a bounding range for the development of life on other planets, in the context of terraforming. Much of earth's biomass (~60%) relies on photosynthesis for an energy source, while a further ~40% is chemotropic[18]. For the development of life on other planetary bodies, chemical energy may have been critical[18], while for sustaining life on another planetary body in our solar system, sufficiently high solar energy may also be necessary for phototrophic organisms.

Water Requirements

All known life requires water[19]; thus the capacity for planetary body to sustain water is a critical aspect of habitability. The "Habitable Zone" of a solar system is generally defined as the region in which stable surface liquid water may be present on a planetary body[19][22]. The boundaries of the Habitable Zone were originally defined by water loss by photolysis and hydrogen escape, setting a limit on how close a planet may be to its orbited star, and the prevalence of CO2 clouds that would increase albedo, setting an outer boundary on stable liquid water[22]. These constraints are applicable in particular to Earth-like planets and would not as easily apply to icy moons like Europa and Enceladus.

Energy Requirements

On the most fundamental level, the only absolute requirement of life may be thermodynamic disequilibrium, or the presence of Gibbs Free Energy[19]. It has been argued that habitability can be conceived of as a balance between life's demand for energy and the capacity for the environment to provide such energy[19]. For humans, energy comes in the form of sugars, fats, and proteins provided by consuming plants and animals, necessitating in turn that a habitable planet for humans can sustain such organisms[23].

Elemental Requirements

On earth, life generally requires six elements in high abundance: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous, and sulfur[20]. These elements are considered "essential" for all known life and plentiful within biological systems[3]. Additional elements crucial to life include the cations Mg2+, Ca2+, K+ and Na+ and the anion Cl-[3]. Many of these elements may undergo biologically facilitated oxidation or reduction to produce usable metabolic energy[3][24].

Preliminary stages

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Once conditions become more suitable for life of the introduced species, the importation of microbial life could begin.[13] As conditions approach that of Earth, plant life could also be brought in. This would accelerate the production of oxygen, which theoretically would make the planet eventually able to support animal life.

Prospective targets

Mars

In many respects, Mars is the most Earth-like planet in the Solar System.[25][26] It is thought that Mars once had a more Earth-like environment early in its history, with a thicker atmosphere and abundant water that was lost over the course of hundreds of millions of years.[27]

The exact mechanism of this loss is still unclear, though three mechanisms, in particular, seem likely: First, whenever surface water is present, carbon dioxide (CO

2) reacts with rocks to form carbonates, thus drawing atmosphere off and binding it to the planetary surface. On Earth, this process is counteracted when plate tectonics works to cause volcanic eruptions that vent carbon dioxide back to the atmosphere. On Mars, the lack of such tectonic activity worked to prevent the recycling of gases locked up in sediments.[28]

Second, the lack of a magnetosphere around Mars may have allowed the solar wind to gradually erode the atmosphere.[28] Convection within the core of Mars, which is made mostly of iron,[29] originally generated a magnetic field. However the dynamo ceased to function long ago,[30] and the magnetic field of Mars has largely disappeared, probably due to "loss of core heat, solidification of most of the core, and/or changes in the mantle convection regime."[31] Results from the NASA MAVEN mission show that the atmosphere is removed primarily due to Coronal Mass Ejection events, where outbursts of high-velocity protons from the Sun impact the atmosphere. Mars does still retain a limited magnetosphere that covers approximately 40% of its surface. Rather than uniformly covering and protecting the atmosphere from solar wind, however, the magnetic field takes the form of a collection of smaller, umbrella-shaped fields, mainly clustered together around the planet's southern hemisphere.[32]

Finally, between approximately 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago, asteroid impacts during the Late Heavy Bombardment caused significant changes to the surface environment of objects in the Solar System. The low gravity of Mars suggests that these impacts could have ejected much of the Martian atmosphere into deep space.[33]

Terraforming Mars would entail two major interlaced changes: building the atmosphere and heating it.[34] A thicker atmosphere of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide would trap incoming solar radiation. Because the raised temperature would add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, the two processes would augment each other.[35] Carbon dioxide alone would not suffice to sustain a temperature above the freezing point of water, so a mixture of specialized greenhouse molecules might be manufactured.[36]

Venus

Terraforming Venus requires two major changes: removing most of the planet's dense 9 MPa (1,300 psi; 89 atm) carbon dioxide atmosphere, and reducing the planet's 450 °C (842 °F) surface temperature.[37][38] These goals are closely interrelated because Venus's extreme temperature may result from the greenhouse effect caused by its dense atmosphere.

Venus’s atmosphere currently contains little oxygen, so an additional step would be to inject breathable O2 into the atmosphere. An early proposal for such a process comes from Carl Sagan, who suggested the injection of floating, photosynthetic bacteria into the Venusian atmosphere to reduce CO2 to organic form, and increase the atmospheric concentration of O2 in the atmosphere.[1] This concept, however, was based in a flawed 1960s understanding of Venus’s atmosphere as much lower pressure; in reality, the Venusian atmospheric pressure (93 bars) is far higher than early estimates. Sagan’s idea is therefore untenable, as he later conceded.[39]

An additional step noted by Martin Beech includes the injection of water and/or hydrogen into the planetary atmosphere;[3] this step follows after sequestering CO2 and reducing the mass of the atmosphere. In order to combine hydrogen with O2 produced by other means, an estimated 4*1019 kg of hydrogen is necessary; this may need to be mined from another source, such as Uranus or Neptune.[3]

Mercury

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Although usually disregarded as being too hot, Mercury may in fact be one of the easiest bodies in the solar system to terraform. Mercury's magnetic field is only 1.1% that of Earth's but it is thought that Mercury's magnetic field should be much stronger, up to 30% of Earth's, if it weren't being suppressed by certain solar wind effects.[40] It is thought[by whom?] that Mercury's magnetic field was suppressed after "stalling" at some point in the past (possibly caused by the Caloris basin impact) and, if given a temporary "helping hand" by shielding Mercury from solar wind by placing an artificial magnetic shield at Mercury-Sun L1 (similar to the proposal for Mars), then Mercury's magnetic field would "inflate" and grow in intensity 30 times stronger at which point Mercury's magnetic field would be self sustaining provided the field wasn't made to "stall" by another celestial event.[citation needed]

Despite being much smaller than Mars, Mercury has a gravity nearly identical in strength to Mars due to its increased density and could, with a now augmented magnetosphere, hold a nitrogen/oxygen atmosphere for millions of years.

To provide this atmosphere, 3.5×1017 kilograms of water could be delivered by a similar process as proposed for Venus by launching a stream of kinetic impactors at Hyperion (the moon of Saturn) causing it to be ejected and flung into the inner solar system. Once this water has been delivered, Mercury could be covered in a thin layer of doped titanium dioxide photo-catalyst dust which would split the water into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen molecules, with the hydrogen rapidly being lost to space and a 0.2-0.3 bar atmosphere of pure oxygen being left behind in less than 70 years (assuming an efficiency of 30-40%).[citation needed] At this point the atmosphere would be breathable and nitrogen may be added as required to allow for plant growth in the presence of nitrates.

Temperature management may not be required, despite an equilibrium average temperature of ~159 Celsius. Millions of square kilometers at the poles have an average temperature of 0-50 Celsius, or 32-122 Fahrenheit (an area the size of Mexico at each pole with habitable temperatures). The total habitable area is likely to be even larger given that the previously mentioned photo-catalyst dust would raise the albedo from 0.12 to ~0.6, lowering the global average temperature to tens of degrees and potentially increasing the habitable area. The temperature could be further managed with the usage of solar shades.[citation needed]

Mercury has the potential to be the fastest celestial body to terraform at least partially, giving it a thin but breathable atmosphere with human-survivable pressures, a strong magnetic field, with at least a small percentage of its land at survivable temperatures at closer to the north and south poles provided water content could be constrained to avoid a runaway greenhouse effect.

Moon

Although the gravity on Earth's moon is too low to hold an atmosphere for geological spans of time, if given one, it would retain it for spans of time that are long compared to human lifespans.[41][42] Landis[42] and others[43][44] have thus proposed that it could be feasible to terraform the moon, although not all agree with that proposal.[45] Landis estimates that a 1 PSI atmosphere of pure oxygen on the moon would require on the order of two hundred trillion tons of oxygen, and suggests it could be produced by reducing the oxygen from an amount of lunar rock equivalent to a cube about fifty kilometers on an edge. Alternatively, he suggests that the water content of "fifty to a hundred comets" the size of Halley's comet would do the job, "assuming that the water doesn't splash away when the comets hit the moon."[42] Likewise, Benford calculates that terraforming the moon would require "about 100 comets the size of Halley's."[43]

Earth

It has been recently proposed[when?] that due to the effects of climate change, an interventionist program might be designed to return Earth to pre-industrial climate parameters. In order to achieve this, multiple solutions have been proposed, such as the management of solar radiation, the sequestration of carbon dioxide using geoengineering methods, and the design and release of climate altering genetically engineered organisms.[46][47]

Other bodies in the Solar System

Other possible candidates for terraforming (possibly only partial or paraterraforming) include large moons of Jupiter or Saturn (Titan, Callisto, Ganymede, Europa, Enceladus), and the dwarf planet Ceres.

Other possibilities

Biological terraforming

Many proposals for planetary engineering involve the use of genetically engineered bacteria.[48][49]

As synthetic biology matures over the coming decades it may become possible to build designer organisms from scratch that directly manufacture desired products efficiently.[50] Lisa Nip, Ph.D. candidate at the MIT Media Lab's Molecular Machines group, said that by synthetic biology, scientists could genetically engineer humans, plants and bacteria to create Earth-like conditions on another planet.[51][52]

Gary King, microbiologist at Louisiana State University studying the most extreme organisms on Earth, notes that "synthetic biology has given us a remarkable toolkit that can be used to manufacture new kinds of organisms specially suited for the systems we want to plan for" and outlines the prospects for terraforming, saying "we'll want to investigate our chosen microbes, find the genes that code for the survival and terraforming properties that we want (like radiation and drought resistance), and then use that knowledge to genetically engineer specifically Martian-designed microbes". He sees the project's biggest bottleneck in the ability to genetically tweak and tailor the right microbes, estimating that this hurdle could take "a decade or more" to be solved. He also notes that it would be best to develop "not a single kind of microbe but a suite of several that work together".[53]

DARPA is researching the use of photosynthesizing plants, bacteria, and algae grown directly on the Mars surface that could warm up and thicken its atmosphere. In 2015 the agency and some of its research partners created an software called DTA GView − a 'Google Maps of genomes', in which genomes of several organisms can be pulled up on the program to immediately show a list of known genes and where they are located in the genome. According to Alicia Jackson, deputy director of DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, they have developed a "technological toolkit to transform not just hostile places here on Earth, but to go into space not just to visit, but to stay".[54][55][56][57]

Paraterraforming

Also known as the "world house" concept, para-terraforming involves the construction of a habitable enclosure on a planet that encompasses most of the planet's usable area.[58] The enclosure would consist of a transparent roof held one or more kilometers above the surface, pressurized with a breathable atmosphere, and anchored with tension towers and cables at regular intervals. The world house concept is similar to the concept of a domed habitat, but one which covers all (or most) of the planet.

Adapting humans

It has also been suggested that instead of or in addition to terraforming a hostile environment humans might adapt to these places by the use of genetic engineering, biotechnology and cybernetic enhancements.[59][60][61][62][63]

Issues

Ethical issues

There is a philosophical debate within biology and ecology as to whether terraforming other worlds is an ethical endeavor. From the point of view of a cosmocentric ethic, this involves balancing the need for the preservation of human life against the intrinsic value of existing planetary ecologies.[64] Lucianne Walkowicz has even called terraforming a "planetary-scale strip mining operation".[65]

On the pro-terraforming side of the argument, there are those like Robert Zubrin, Martyn J. Fogg, Richard L. S. Taylor, and the late Carl Sagan who believe that it is humanity's moral obligation to make other worlds suitable for human life, as a continuation of the history of life-transforming the environments around it on Earth.[66][67] They also point out that Earth would eventually be destroyed if nature takes its course, so that humanity faces a very long-term choice between terraforming other worlds or allowing all terrestrial life to become extinct. Terraforming totally barren planets, it is asserted, is not morally wrong as it does not affect any other life.

The opposing argument posits that terraforming would be an unethical interference in nature, and that given humanity's past treatment of Earth, other planets may be better off without human interference.[citation needed] Still others strike a middle ground, such as Christopher McKay, who argues that terraforming is ethically sound only once we have completely assured that an alien planet does not harbor life of its own; but that if it does, we should not try to reshape it to our own use, but we should engineer its environment to artificially nurture the alien life and help it thrive and co-evolve, or even co-exist with humans.[68] Even this would be seen as a type of terraforming to the strictest of ecocentrists, who would say that all life has the right, in its home biosphere, to evolve without outside interference.

Economic issues

The initial cost of such projects as planetary terraforming would be massive, and the infrastructure of such an enterprise would have to be built from scratch. Such technology has not yet been developed, let alone financially feasible at the moment. John Hickman has pointed out that almost none of the current schemes for terraforming incorporate economic strategies, and most of their models and expectations seem highly optimistic.[69]

Political issues

National pride, rivalries between nations, and the politics of public relations have in the past been the primary motivations for shaping space projects.[70][71] It is reasonable to assume[by whom?] that these factors would also be present in planetary terraforming efforts.[citation needed]

In popular culture

Terraforming is a common concept in science fiction, ranging from television, movies and novels to video games.[72]

A related concept from science fiction is xenoforming – a process in which aliens change the Earth or other planets to suit their own needs, already suggested in the classic The War of the Worlds (1898) of H.G. Wells.[73]

See also

- Astrobotany – Study of plants grown in spacecraft

- Climate engineering, also known as Geoengineering – Deliberate and large-scale intervention in the Earth's climate system

- Colonization of Mars – Proposed concepts for human settlements on Mars

- Colonization of Venus – Proposed colonization of the planet Venus

- Desert greening – Process of man-made reclamation of deserts

- Effect of spaceflight on the human body – Medical issues associated with spaceflight

- Extraterrestrial liquid water – Liquid water naturally occurring outside Earth

- Health threat from cosmic rays – Dangers posed to astronauts

- In situ resource utilization – Astronautical use of materials harvested in outer space

- Pantropy – Hypothetical process of space colonization

- Planetary engineering – Influencing a planet's global environments

- Planetary habitability – Known extent to which a planet is suitable for life

- Space colonization – Concept of permanent human habitation outside of Earth

- Terraforming of Mars – Hypothetical modification of Mars into a habitable planet

- Terraforming of Venus – Engineering the global environment of Venus to make it suitable for humans

Notes

- ^ a b c Sagan, Carl (1961). "The Planet Venus". Science. 133 (3456): 849–58. Bibcode:1961Sci...133..849S. doi:10.1126/science.133.3456.849. PMID 17789744.

- ^ "Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: terraforming". Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ a b c d e f Beech, Martin (21 April 2009). Terraforming: The Creating of Habitable Worlds. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-387-09796-1. "The present economic fashion of favoring short-term gain over long term investment will never be able to support a terraforming project." Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Sagan 1997, pp. 276–7.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (December 1973). "Planetary engineering on Mars". Icarus. 20 (4): 513–514. Bibcode:1973Icar...20..513S. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(73)90026-2.

- ^ Averner & MacElroy 1976, pp. front cover, study results.

- ^ Oberg, James Edward (1981). New Earths: Restructuring Earth and Other Planets. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

- ^ McKay, Christopher P. (January 1982). "On Terraforming Mars". Extrapolation. 23 (4): 309–314. doi:10.3828/extr.1982.23.4.309.

- ^ Lovelock, James & Allaby, Michael (1984). The Greening of Mars. ISBN 9780446329675.

- ^ Haynes, RH (1990), "Ecce Ecopoiesis: Playing God on Mars", in MacNiven, D. (1990-07-13), Moral Expertise: studies in practical and professional ethics, Routledge. pp. 161–163. ISBN 0-415-03576-7.

- ^ οἶκος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ ποίησις in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ a b c Fogg, Martyn J. (1995). Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments. SAE International, Warrendale, PA.

- ^ Lopez, Jose V; Peixoto, Raquel S; Rosado, Alexandre S (22 August 2019). "Inevitable future: space colonization beyond Earth with microbes first". FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 95 (10). doi:10.1093/femsec/fiz127. PMC 6748721. PMID 31437273.

- ^ Fogg, 1996

- ^ Fogg, Martyn J. (1995). Terraforming : engineering planetary environments. Society of Automotive Engineers. ISBN 1560916095. OCLC 32348444.

- ^ Hoehler, Tori M. (2007-12-28). "An Energy Balance Concept for Habitability". Astrobiology. 7 (6): 824–838. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.0095. ISSN 1531-1074.

- ^ a b c d Lineweaver, Charles H.; Chopra, Aditya (2012-05-30). "The Habitability of Our Earth and Other Earths: Astrophysical, Geochemical, Geophysical, and Biological Limits on Planet Habitability". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 40 (1): 597–623. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105531. ISSN 0084-6597.

- ^ a b c d e Hoehler, Tori M.; Som, Sanjoy M.; Kiang, Nancy Y. (2018), Deeg, Hans J.; Belmonte, Juan Antonio (eds.), "Life's Requirements", Handbook of Exoplanets, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–22, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30648-3_74-1, ISBN 978-3-319-30648-3, retrieved 2023-03-14

- ^ a b Cockell, C.S.; Bush, T.; Bryce, C.; Direito, S.; Fox-Powell, M.; Harrison, J.P.; Lammer, H.; Landenmark, H.; Martin-Torres, J.; Nicholson, N.; Noack, L.; O'Malley-James, J.; Payler, S.J.; Rushby, A.; Samuels, T. (2016-01-20). "Habitability: A Review". Astrobiology. 16 (1): 89–117. doi:10.1089/ast.2015.1295. ISSN 1531-1074.

- ^ "Astrobiology Roadmap". web.archive.org. 2011-01-17. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ a b Kasting, James F.; Whitmire, Daniel P.; Reynolds, Ray T. (1993-01-01). "Habitable Zones around Main Sequence Stars". Icarus. 101 (1): 108–128. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1010. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ "Cell Energy, Cell Functions | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ Falkowski, Paul G.; Fenchel, Tom; Delong, Edward F. (2008-05-23). "The Microbial Engines That Drive Earth's Biogeochemical Cycles". Science. 320 (5879): 1034–1039. doi:10.1126/science.1153213. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Read and Lewis 2004, p.16

- ^ Kargel 2004, pp. 185–6.

- ^ Kargel 2004, 99ff

- ^ a b Forget, Costard & Lognonné 2007, pp. 80–2.

- ^ Dave Jacqué (2003-09-26). "APS X-rays reveal secrets of Mars' core". Argonne National Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ^ Schubert, Turcotte & Olson 2001, p. 692

- ^ Carr, Michael H.; Bell, James F. (2014). "Mars". Encyclopedia of the Solar System. pp. 359–377. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-415845-0.00017-7. ISBN 978-0-12-415845-0.

- ^ Solar Wind, 2008

- ^ Forget, Costard & Lognonné 2007, pp. 80.

- ^ Faure & Mensing 2007, p. 252.

- ^ Zubrin, Robert; McKay, Christopher (1993). "Technological requirements for terraforming Mars". 29th Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit. doi:10.2514/6.1993-2005.

- ^ Gerstell, M. F.; Francisco, J. S.; Yung, Y. L.; Boxe, C.; Aaltonee, E. T. (27 February 2001). "Keeping Mars warm with new super greenhouse gases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (5): 2154–2157. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2154G. doi:10.1073/pnas.051511598. PMC 30108. PMID 11226208.

- ^ Fogg, M. J. (1987). "The terraforming of Venus". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 40: 551. Bibcode:1987JBIS...40..551F.

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey (2011). "Terraforming Venus: A Challenging Project for Future Colonization". AIAA SPACE 2011 Conference & Exposition. doi:10.2514/6.2011-7215. ISBN 978-1-60086-953-2.

- ^ Sagan, Carl (1994). Pale blue dot : a vision of the human future in space (First ed.). New York. ISBN 0-679-76486-0. OCLC 30736355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gómez‐Pérez, Natalia; Solomon, Sean C. (2010). "Mercury's weak magnetic field: A result of magnetospheric feedback?". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (20): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3720204G. doi:10.1029/2010GL044533. ISSN 1944-8007.

- ^ Oberg, James. "New Earths". jamesoberg.com.

- ^ a b c Landis, Geoffrey (June 1990). "Air Pollution on the Moon". Analog.

- ^ a b Benford, Greg (July 14, 2014). "How to Terraform the Moon". Slate. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Williams, Matt (March 31, 2016). "How Do We Terraform the Moon?". Universe Today. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce (July 27, 2016). "Why The Moon Should Never Be Terraformed". Forbes. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Solé, Ricard V.; Montañez, Raúl; Duran-Nebreda, Salva (18 July 2015). "Synthetic circuit designs for earth terraformation". Biology Direct. 10 (1): 37. arXiv:1503.05043. Bibcode:2015arXiv150305043S. doi:10.1186/s13062-015-0064-7. PMC 4506446. PMID 26187273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Solé, Ricard V.; Montañez, Raúl; Duran-Nebreda, Salva; Rodriguez-Amor, Daniel; Vidiella, Blai; Sardanyés, Josep (4 July 2018). "Population dynamics of synthetic terraformation motifs". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (7): 180121. Bibcode:2018RSOS....580121S. doi:10.1098/rsos.180121. PMC 6083676. PMID 30109068.

- ^ Hiscox, Juliana A.; Thomas, David J. (October 1995). "Genetic modification and selection of microorganisms for growth on Mars". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 48 (10): 419–26. PMID 11541203.

- ^ "Mercury". The Society. 29. 2000. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Menezes, Amor A.; Cumbers, John; Hogan, John A.; Arkin, Adam P. (6 January 2015). "Towards synthetic biological approaches to resource utilization on space missions". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 12 (102): 20140715. doi:10.1098/rsif.2014.0715. PMC 4277073. PMID 25376875.

- ^ "Video: Humans Could Engineer Themselves for Long-Term Space Travel". Live Science. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Brown, Kristen V. (29 March 2016). "You Can Now Play God From The Comfort Of Your Garage". Fusion. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Herkewitz, William (7 May 2015). "Here's How We'll Terraform Mars With Microbes". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Will tweaked microbes make Mars Earth-like?". The Times of India. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Koebler, Jason (24 June 2015). "DARPA: We Are Engineering the Organisms That Will Terraform Mars". Vice Motherboard. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Smith, Chris (25 June 2015). "We Definitely Want to Live on Mars – Here's How We Plan to Tame the Red Planet". BGR. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Depra, Dianne (27 June 2015). "DARPA Wants To Use Genetically Engineered Organisms To Make Mars More Earth-Like". Tech Times. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Taylor, 1992

- ^ Gronstal, Aaron; Perez, Julio Aprea; Bittner, Tobias; Clacey, Erik; Grubisic, Angelo; Rogers, Damian (2005). Bioforming and terraforming: A balance of methods for feasible space colonization. 56th International Astronautical Congress.

- ^ Lunan, Duncan (January 1983). Man and the Planets: The Resources of the Solar System. Ashgrove Press. ISBN 9780906798171. Retrieved 10 January 2017.[page needed]

- ^ Spitzmiller, Ted (2007). Astronautics: A Historical Perspective of Mankind's Efforts to Conquer the Cosmos. Apogee Books. ISBN 9781894959667. Retrieved 10 January 2017.[page needed]

- ^ Cain, Fraser (10 January 2017). "Could We Marsiform Ourselves?". Universe Today. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky (29 July 2013). "Be Your Own Spaceship: How We Can Adapt Human Bodies for Alien Worlds". Vice Motherboard. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ MacNiven 1995

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (November 20, 2018). "Decolonizing Mars: Are We Thinking About Space Exploration All Wrong?". Gizmodo. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Robert Zubrin, The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must, pp. 248–249, Simon & Schuster/Touchstone, 1996, ISBN 0-684-83550-9

- ^ Fogg 2000

- ^ Christopher McKay and Robert Zubrin, "Do Indigenous Martian Bacteria have Precedence over Human Exploration?", pp. 177–182, in On to Mars: Colonizing a New World, Apogee Books Space Series, 2002, ISBN 1-896522-90-4

- ^ Hickman, John (November 1999). "The Political Economy of Very Large Space Projects". Journal of Evolution and Technology. 4: 1–14. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- ^ "China's Moon Quest Has U.S. Lawmakers Seeking New Space Race". Bloomberg. 2006-04-19. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-04-28.

- ^ Thompson 2001 p. 108

- ^ "SFE: Terraforming". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ "Themes : Xenoforming : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-08-24.

References

- Averner, M. M.; MacElroy, R. D., eds. (1976). On the Habitability of Mars: An Approach to Planetary Ecosynthesis. NASA. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- "Solar wind ripping chunks off Mars". Cosmos. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2012-04-27. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2004). Ancient Earth, ancient skies: the age of Earth and its cosmic surroundings. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4933-7

- Faure, Gunter & Mensing, Teresa M. (2007). Introduction to planetary science: the geological perspective. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-5233-2.

- Fogg, Martyn J. (1995). Terraforming: Engineering Planetary Environments. SAE International, Warrendale, PA. ISBN 1-56091-609-5.

- Fogg, Martyn J. (1996). "A Planet Dweller's Dream". In Schmidt, Stanley; Zubrin, Robert (eds.). Islands in the Sky. New York: Wiley. pp. 143–67.

- Fogg, Martyn J. (1998). "Terraforming Mars: A Review of Current Research" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 2 (3). Committee on Space Research: 415–420. Bibcode:1998AdSpR..22..415F. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(98)00166-5.

- Fogg, Martyn J. (2000). The Ethical Dimensions of Space Settlement (PDF format). Space Policy, 16, 205–211. Also presented (1999) at the 50th International Astronautical Congress, Amsterdam (IAA-99-IAA.7.1.07).

- Forget, François; Costard, François & Lognonné, Philippe (2007). Planet Mars: Story of Another World. Springer. ISBN 0-387-48925-8.

- Kargel, Jeffrey Stuart (2004). Mars: a warmer, wetter planet. Springer. ISBN 1-85233-568-8.

- Knoll, Andrew H. (2008). "Cyanobacteria and earth history". In Herrero, Antonia; Flores, Enrique (eds.). The cyanobacteria: molecular biology, genomics, and evolution. Horizon Scientific Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-904455-15-8.

- MacNiven, D. (1995). "Environmental Ethics and Planetary Engineering". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 48: 441–44.

- McKay Christopher P. & Haynes, Robert H. (1997). "Implanting Life on Mars as a Long Term Goal for Mars Exploration", in The Case for Mars IV: Considerations for Sending Humans, ed. Thomas R. Meyer (San Diego, California: American Astronautical Society/Univelt), Pp. 209–15.

- Read, Peter L.; Lewis, Stephen R. (2004). The Martian climate revisited: atmosphere and environment of a desert planet. Springer. ISBN 3-540-40743-X.

- Sagan, Carl & Druyan, Ann (1997). Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-37659-5.

- Schubert, Gerald; Turcotte, Donald L.; Olson, Peter. (2001). Mantle convection in the Earth and planets. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79836-1.

- Taylor, Richard L. S. (1992). "Paraterraforming – The world house concept". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, vol. 45, no. 8, pp. 341–352. ISSN 0007-084X. Bibcode:1992JBIS...45..341T.

- Thompson, J. M. T. (2001). Visions of the future: astronomy and Earth science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80537-6.

External links

- New Mars forum

- Terraformers Society of Canada

- Visualizing the steps of solar system terraforming

- Research Paper: Technological Requirements for Terraforming Mars

- Terraformers Australia

- Terraformers UK

- The Terraformation of Worlds Archived 2019-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Terraformation de Mars

- Fogg, Martyn J. The Terraforming Information Pages

- BBC article on Charles Darwin's and Joseph Hooker's artificial ecosystem on Ascension Island that may be of interest to terraforming projects

- Choi, Charles Q. (November 1, 2010). "Bugs in Space: Microscopic miners could help humans thrive on other planets". Scientific American.

- Robotic Lunar Ecopoiesis Test Bed Principal Investigator: Paul Todd (2004)