History of the Regency of Algiers: Difference between revisions

Scope creep (talk | contribs) Put Saidouni 2009 back |

Scope creep (talk | contribs) →Further reading: Single FR entry remaining |

||

| Line 458: | Line 458: | ||

*<!--Allioui-->{{cite book |last1=Allioui |first1=Youcef |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-rYuAQAAIAAJ |title=Les Archs, tribus berbères de Kabylie: histoire, résistance, culture et démocratie |date=2006 |publisher=L'Harmattan |isbn=978-2-296-01363-6 |page= |language=fr |trans-title=The Archs, Berber tribes of Kabylia: history, resistance, culture and democracy |oclc=71888091}} |

*<!--Allioui-->{{cite book |last1=Allioui |first1=Youcef |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-rYuAQAAIAAJ |title=Les Archs, tribus berbères de Kabylie: histoire, résistance, culture et démocratie |date=2006 |publisher=L'Harmattan |isbn=978-2-296-01363-6 |page= |language=fr |trans-title=The Archs, Berber tribes of Kabylia: history, resistance, culture and democracy |oclc=71888091}} |

||

*<!--Murray-Miller-->{{cite book |last1=Murray-Miller |first1=Gavin |title=The Cult of the Modern: Trans-Mediterranean France and the Construction of French Modernity. |publisher=U of Nebraska Press |year=2017 |isbn=978-1-4962-0031-0 |series=France overseas |oclc=971021058}} |

|||

*<!--Naylor-->{{Cite book |last=Naylor |first=Phillip C. |title=Historical Dictionary of Algeria |date=2006 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-8108-7919-5 |series=Historical dictionaries of Africa (Unnumbered) |oclc=909370108}} |

|||

*<!--Nyrop-->{{cite book |last1=Nyrop |first1=Richard F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h7_OflKe6EUC&pg=PA16 |title=Area Handbook for Algeria |date=1972 |publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |series=DA Pam, 550-44 |page= |language=en |oclc=693596}} |

|||

*<!--Panzac -->{{cite book |last1=Panzac |first1=Daniel |title=Histoire économique et sociale de l'Empire ottoman et de la Turquie (1326-1960): actes du sixième congrès international tenu à Aix-en-Provence du 1er au 4 juillet 1992 |publisher=Peeters Publishers |year=1995 |isbn=978-90-6831-799-2 |series=Collection Turcica |volume=8 |trans-title=Economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey (1326-1960): Proceedings of the sixth international congress held in Aix-en-Provence from July 1 to 4, 1992 |oclc=611664277}} |

|||

*<!--Plantet-->{{cite book |url=https://www.cnplet.dz/images/bibliotheque/Autres/Correspondance-des-Deys-d-Alger-avec-la-Cour-de-France-Tome-1.pdf |title=Correspondance des deys d'Alger avec la cour de France 1579 — 1833 <!--subtitle=Recueillie dans les dépôts d'archives des affaires étrangères, de la marine, des colonies et de la chambre de commerce de Marseille--> |date=1889 |publisher=Félix Alcan |editor1-last=Plantet |editor1-first=Eugène |volume=1 (1579–1700) |location=Paris |trans-title=Correspondence of the Deys of Algiers with the Court of France 1579 — 1833) |oclc=600730173 <!--alt-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bAlXAAAAMAAJ&&pg=PAXXI-->}} |

|||

*<!--Rashid-->{{Cite book |last=Rashid |first=Mahbub |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UvU1EAAAQBAJ&dq=algiers+stone+quarry+dey&pg=PA303 |title=Physical Space and Spatiality in Muslim Societies: Notes on the Social Production of Cities |date=2021 |publisher=University of Michigan Press |isbn=978-0-472-13250-8 |oclc=1245237873}} |

|||

*<!--Shaler-->{{Cite book |last=Shaler |first=William |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_sYRAAAAYAAJ&q=16 |title=Sketches of Algiers, Political, Historical, and Civil: Containing an Account of the Geography, Population, Government, Revenues, Commerce, Agriculture, Arts, Civil Institutions, Tribes, Manners, Languages, and Recent Political History of that Country |date=1826 |publisher=Cummings, Hilliard |language=en |oclc=958750685}} |

|||

*<!--Shannon-->{{Cite book |last=Shannon |first=Jonathan Holt |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=67PdCQAAQBAJ&dq=algiers+music+ottoman&pg=PA48 |title=Performing al-Andalus: Music and Nostalgia across the Mediterranean |date=2015 |publisher=Indiana University Press |isbn=978-0-253-01774-1 |series=Public cultures of the Middle East and North Africa |oclc=914463206}} |

|||

*<!--Shillington-->{{Cite book |last=Shillington |first=Kevin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=umyHqvAErOAC&q=Encyclopedia+of+african+history+vol+3 |title=Encyclopedia of African History |date=2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-135-45670-2 |volume=3}} |

|||

*<!--Sluglett-->{{cite book |last1=Sluglett |first1=Peter |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XjxyBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA68 |title=Atlas of Islamic History |date=2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-58897-9 |doi=10.4324/9781315743387 |oclc=902673654}} |

|||

*<!--Somel-->{{cite book |last1=Somel |first1=Selcuk Aksin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tBoyoNNKh78C&pg=PA16 |title=The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire |date=2010 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-8108-7579-1 |pages= |language=en |oclc=1100851523}} |

|||

*<!--Tikka-->{{Cite book |last1=Tikka |first1=Katja |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VazpEAAAQBAJ |title=Managing Mobility in Early Modern Europe and its Empires: Invited, Banished, Tolerated |last2=Uusitalo |first2=Lauri |last3=Wyżga |first3=Mateusz |date=2023 |publisher=Springer Nature |isbn=978-3-031-41889-1 |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-41889-1 |oclc=1415897393}} |

|||

*<!--Thomson-->{{Cite book |last=Thomson |first=Ann |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tqIauiQohfMC&dq=regency+of+algiers+montesquieu&pg=PA114 |title=Barbary and Enlightenment: European Attitudes Towards the Maghreb in the 18th Century |date=1987 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-08273-1 |series=Brill's studies in intellectual history |volume=2 |oclc=15163796}} |

|||

*<!--Vatin-->{{cite journal |last1=Vatin |first1=Jean-Claude |date=1982 |title=Introduction générale. Appréhensions et compréhension du Maghreb précolonial (et colonial). |trans-title=General Introduction. Apprehensions and understanding of the precolonial (and colonial) Maghreb |journal=Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée |volume=33 |pages=13–16 |doi=10.3406/remmm.1982.1938 |access-date=6 June 2023 |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/remmm_0035-1474_1982_num_33_1_1938 |oclc=4649486490}} |

|||

*<!--Verdès-Leroux-->{{cite book |last1=Verdès-Leroux |first1=Jeannine |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s5kPAQAAMAAJ |title=L'Algérie et la France |date=2009 |publisher=Robert Laffont |isbn=978-2-221-10946-5 |series=Bouquins |pages= |language=fr |trans-title=Algeria and France |oclc=332257086}} |

|||

*<!--Wright-->{{cite book |last1=Wright |first1=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=akF_AgAAQBAJ&dq=algiers+destination+trans-saharan&pg=PT51 |title=The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade |date=2007 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-17986-2 |language=en |oclc=1134179863}} |

|||

*<!--Yacono-->{{cite book |last1=Yacono |first1=Xavier |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wZkFAQAAIAAJ |title=Histoire de l'Algérie: De la fin de la Régence turque à l'insurrection de 1954 |date=1993 |publisher=Éditions de l'Atlanthrope |isbn=978-2-86442-032-3 |trans-title=History of Algeria: From the end of the Turkish Regency to the insurrection of 1954 |oclc=29854363}} |

|||

[[Category:Regency of Algiers|-]] |

[[Category:Regency of Algiers|-]] |

||

Revision as of 18:35, 4 June 2024

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

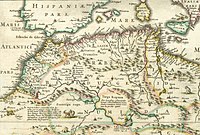

The Regency of Algiers was a largely independent tributary state of the Ottoman Empire that existed between 1516 and 1830. Algiers, along with Tunis and Tripoli, were known in Europe as the Barbary States. In Ottoman terminology these areas were called Garb Ocakları (western garrisons). founded by the corsair brothers Aruj and Khayr ad-Din Barbarossa, Algiers was involved in numerous armed conflicts with the European powers throughout its history. The Regency was an important pirate base, notorious for its Barbary corsairs, which was initially ruled by Ottoman governors (who often also held the office of Kapudan Pasha) and later by elected military sovereigns. The state financed itself mainly through privateering and the slave trade; its ships captured European merchant ships, plundered coastal regions as far as Iceland and waged a "holy war" against the Christian powers of Europe. Algiers also asserted its dominance against neighboring Maghrebi states, imposing tribute and border delimitation on Tunisian and Moroccans sovereigns. For more than three centuries, Spain, France, British, Dutch and later the U.S. navies fought the Barbary states and were able to inflict heavy defeats on Algiers in the 19th century for the first time. The decline of piracy eventually led to a decline in state revenues. Attempts to make up for this gap through increased taxation led to internal unrest. Violent tribal revolts broke out, led mainly by Marabout orders such as the Darqawiyya and Tijānīya. France took advantage of this domestic political situation to invade in 1830. The French conquest of Algeria ultimately led to French colonial rule, which only ended in 1962.

Establishment (1516–1533)

Spanish expansion in the Maghreb

In ports along the Maghreb coast conquered after the Emirate of Granada fell in 1492, the Spanish Empire established garrisons at walled and fortified defensive strongpoints called presidios.[1] First Melilla fell in 1497,[2] then the Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera in 1508. On the Algerian coast, Mers El Kébir fell in 1505, followed in 1509 by Oran, the most important seaport of the time, directly linked to Tlemcen, capital of the Zayyanid Kingdom.[3] After the Spanish conquest of Tripoli in 1510, the Hafsids in Tunis decided they did not have the means to resist and submitted to Spanish sovereignty through humiliating agreements.[4] This allowed the Spaniards to control the waystations for caravans from Tripoli, western Sudan, and Tunis in the east and Ceuta and Melilla in the west, on trade routes that passed through Béjaïa, Algiers, Oran and Tlemcen. Control over this trade in gold and slaves became essential to the Spanish treasury.[5]

The Maghreb was no longer the middleman between Europe and Africa it had been, especially in gold. The loss of this trade led to political fragmentation,[6] economic stagnation, and a deterioration of craftsmanship.[7] Weak centralization was exacerbated by the trade monopoly of Spain and its merchant class, and also the Spanish capacity to collect taxes.[8]

Barbarossa brothers arrive

Ottoman privateer brothers Aruj and Hayreddin, both known to Europeans as Barbarossa ("Red Beard"), were corsair chiefs, skilful politicians and warriors feared by the Christian armies of the Mediterranean.[9] In 1512, they were successfully operating off the coast of Hafsid Tunisia, famous for victories against Spanish naval vessels on the high sea and off the shores of Andalusia. Scholars and notables of Bejaïa asked them for help in dislodging the Spanish.[10] They failed however, due to Bejaïa's formidable fortifications. Aruj was wounded while trying to storm the city, and his arm had to be amputated.[11] He realized that his forces' position in the valley of La Goulette hampered their efforts against the Spaniards and moved them to Jijel, a center for trade between Africa and Italy, occupied since 1260 by the Genoese, whose inhabitants had asked him for help. Aruj conquered the city in 1514, established a base of operations there and formalized an alliance with the tribal leaders of Kabylia.[12][13] In 1514 Aruj attacked Bejaïa again with a larger force in the spring of the following year, but withdrew when his ammunition ran out and the emir of Tunis refused to supply him with any more.[13] He did however succeed in capturing hundreds of Spanish prisoners.[14]

New masters of Algiers

Pedro Navarro and Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros captured Bejaïa in 1510, after taking Oran in 1509. The leader of Algiers, sheikh Salim al-Tumi of the Thaaliba, recognized Catholic king Ferdinand II of Aragon as his sovereign, and made a number of pledges. He said he would pay tribute every year, release Christian prisoners, forsake piracy, and prevent the enemies of Spain from entering his harbor.[15] To monitor Algiers' compliance with these pledges and observe the residents of Algiers, Pedro Navarro captured the island of Peñon, within artillery range of the city, and put a fort there garrisoned with 200 men.[16] The Algerians sought to break free of the Spanish and took advantage of the excitement over the death of King Ferdinand to send a delegation from Algiers to Jijel in 1516 seeking help from Aruj and his men.[12]

Aruj set out at the head of 5,000 Kabyles and 800 Turkish arquebusiers,[17] while Hayreddin led a naval fleet of 16 galliots. They met up at Algiers,[18] whose population celebrated their arrival and hailed them as heroes.[19] Hayreddin bombarded the Spanish Peñón of Algiers from sea, and Aruj took Cherchell, where he eliminated another Turkish captain who had been cooperating with Andalusians.[12] Aruj was not immediately able to recover the Peñón, and his presence often undermined al-Tumi's authority, so the latter eventually sought the help of the Spaniards to drive him out. Oruc assassinated him,[20] proclaimed himself Sultan of Algiers, and raised his banners in green, yellow, and red above the forts of the city.[21][22][23] The Spaniards reacted by sending the governor of Oran, Diego de Vera, to attack Algiers in late September 1516 with 8000 troops.[24] Aruj allowed De Vera's forces to land then moved against them, taking advantage of the northern wind to pursue them as they retreated, drowning and killing many, and also capturing many prisoners in a total defeat for the Spaniards, and a momentous victory for Aruj,[24] which further expanded his influence in the Algerian heartland.[25]

Campaign of Tlemcen: Death of Aruj

Aruj attacked Spanish vassal Prince of Ténès Hamid bin Abid and seized his city,[24] vanquishing his army at the Battle of Oued Djer in June 1517. He killed the prince and expelled the Spaniards stationed at Ténès. Aruj then divided his kingdom into two parts: an eastern part based in Dellys to be ruled by his brother Hayreddin, and a western part centered on the city of Algiers, to be ruled by him personally.[26] While Aruj was in Ténès, a delegation from Tlemcen arrived to complain about conditions there and the growing threat of the Spanish, exacerbated by squabbling between the Zayyanid princes over the throne.[12] Abu Hammou III had seized power in Tlemcen, expelled his nephew, Abu Zayan III and imprisoning him. Aruj appointed Hayreddin as regent over Algiers and its surroundings[27] and marched towards Tlemcen, capturing the castle of the Banu Rashid along the way, and to protect his rear garrisoned it with a large force led by his brother Isaac. Aruj and his troops entered the city and released Abu Zayan from prison, restoring him to his throne, before progressing westward along the Moulouya to bring the Beni Amer and Beni Snassen tribes under his authority.[28] Abu Zayan began to conspire against Aruj, who arrested and executed him. Meanwhile, the deposed Abu Hammou III fled to Oran to beg for help from his former enemies the Spaniards to retake his throne.[29] The Spaniards chose to help him, capturing the Banu Rashid castle and killing Isaac in late January 1518. Then they began a siege of Tlemcen that was to last six months. Aruj was able to resist for several months but finally locked himself inside the Mechouar palace with 500 Turks for several days to avoid the increasingly hostile populace, who eventually opened the gates for the Spanish in May 1518.[28] Aruj attempted to flee Tlemcen, but the Spaniards pursued and killed him along with his Ottoman companions.[30] His head was then sent to Spain, where it was paraded across its cities and those of Europe. His robes were sent to the Church of St. Jerome in Cordoba, where they were kept as a trophy.[31]

Algiers joins the Ottoman Empire

Hayreddin was proclaimed Sultan of Algiers in late 1519.[32] He increasingly felt a need for Ottoman support to maintain his possessions around Algiers.[33] In early 1520, a delegation of Algerian notables and ulemas led by Sinan Rais arrived in Constantinople,[34] instructed to propose to Ottoman sultan Selim I that Algiers join the Ottoman Empire,[35] making clear to the sultan the strategic importance of Algiers in the Western Mediterranean.[32] Algiers officially became part of the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman I in the spring of 1521,[36] even though Constantinople found the idea of integrating a territory so distant and so close to Spain quite perilous. The Sublime Porte named Hayreddin Barbarossa beylerbey and supported him with 2000 janissaries.[32]

Because of its voluntary membership in the Ottoman Empire, Algiers was considered an estate of the empire, rather than a province. The Regency fleet's important role in Ottoman maritime wars made Algiers the spearhead of Ottoman power in the western Mediterranean.[33][37]

Reconquest of Algiers

After defeating Barbarossa at the Battle of Issers with the joint Kuku-Hafsid forces then capturing Algiers in 1520, Sultan Belkadi ruled over Algiers for five years (1520–1525).[38][39][40] Hayreddin retreated to Jijel in 1521 and allied himself with the Kabyle people of Beni Abbas, rivals of Kuku.[39][41]

Taking advantage of the corsairs' reputation as "holy warriors" and social divisions between urban and rural populations, Hayreddin bolstered his ranks with Andalusi refugees and local tribesmen,[39] taking Collo in 1521, Annaba and Constantine in 1523.[42] He crossed the mountains of Kabylia without incident, and faced Belkadi in Thénia. Belkadi was killed by his own soldiers before a battle could take place.[43] The debacle caused by this assassination cleared the road to Algiers, whose population had complained about Belkadi and opened the gates for Hayreddin in 1525.[44][45]

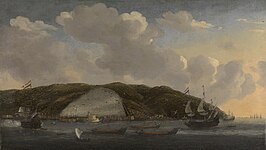

But Algiers was still threatened by the Spaniards, who controlled the port from the Peñon. The Spanish commander, Don Martin de Vargas, rejected a demand for surrender with his garrison of 200 soldiers. Hayreddin bombarded the Peñon and captured it on 27 May 1529.[46][43] Using the Peñon debris, Morisco stonemasons and Christian captive labor, Hayreddin attached the islets to the shore by creating and building a causeway 220 yards (200 m) long, over 80 feet (24 m) wide and 13 feet (4 m) high from a stone breakwater,[38][47] enlarging the harbor into what became a major port and the headquarters of the Algerian corsair fleet.[48]

Morisco rescue missions

In summer 1529 Barbarossa sent ships under Aydin Rais to help Spanish Muslim Moriscos flee the Spanish Inquisition,[46] After he descended in the Valencian coast, captured Christians and taken 200 muslims in his ships, a Spanish squadron was sent under admiral Rodrigo de Portuondo against Aydın Rais in Formentera, where he managed to defeat the attackers, capturing seven ships and their crews, including the dead admiral's son, and freeing 1000 Muslim galley slaves.[49]

In 1531 Barbarossa successfully repelled Andrea Doria's Genoese navy from landing at Cherchell,[50] and set about ferrying about 70,000 refugees to the shores of Algiers.[51][52][53] When there weren't enough ships to carry all the refugees the pirates would shuttle the refugees down the coast to a safer place, leaving them with guards, and go back to rescue another shipload.[53] In Algiers, the Morisco refugees settled in the heights of the city close to the kasbah, in the area known today as the "Tagarin". Others settled in Algerian cities to the east and west, where they built, as Leo Africanus said, "2,000 houses, and among them were those who settled in Morocco and Tunisia. The Maghreb people learned much of their craft, imitated them in their luxury, and rejoiced in them".[53]

Hayreddin's successors (1534–1580)

Barbarossa raided the coasts of Spain and Italy, taking thousands of prisoners in Mahon and Naples.[52] He captured Italian countess Giulia Gonzaga, but she escaped shortly afterward.[54] The sultan called Barbarossa to the Porte in 1533 to become Kapudan Pasha (Admiral). He put Hasan Agha in charge in Algiers as his deputy and went to Constantinople.[55] Two years later in June 1535, Charles V of Spain conquered Tunis, held by Hayreddin at the time.[56]

Algerian expansion

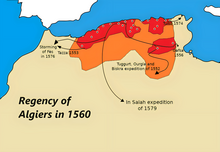

In October 1541 Charles V led another expedition, this time against Algiers, seeking to end the Barbary pirates' dominance of the western Mediterranean.[57] As a storm broke, Hernán Cortés joined an imperial fleet of around 500 ships led by Andrea Doria carrying 24,000 soldiers and 12,000 sailors before Algiers.[58][59][60] Hasan Agha repelled the Maltese knights from the city on 25 October, exhausted and out of dry powder, as increasing winds blew the Spanish ships onto the rocky shore.[60] Under constant assault by Berber cavalry, Charles V led a difficult retreat to the remaining ships at Cap Matifou.[58]

Sources differ on Spanish losses, from 8,000[61] to 12,000 men.[62] They included more than 150 ships as well as 200 cannons, which were recovered for use in the ramparts of Algiers.[63] The slave market of Algiers filled with 4,000 prisoners.[64][61] Hasan Agha received the title of Pasha as a reward,[65] then sent a punitive expedition against the Kabyles of Kuku in 1542.[66]

Successive expeditions tried to take control of the city of Mostaganem. A first expedition set out in 1543, then a second in 1547,[67] in which Martín Alonso Fernández, Count of Alcaudete was defeated due to poor planning, a shortage of ammunition, and a lack of experience and discipline among the Spanish troops.[68]

Hasan Pasha, Hayreddin's son, endeavored to end the see-sawing of Tlemcen's allegiance between Ottomans and Spaniards by taking control of it in 1551.[69] After that, the conquest of Algeria accelerated. In 1552, Salah Rais, with the help of the Kabyle kingdoms of Kuku and Beni Abbas, conquered Touggourt and Ouargla,[70][71] making them tributaries.[72] After leaving a permanent Ottoman garrison in Biskra,[69] Salah Rais expelled the Portuguese from the peñon of Valez and left a garrison there.[70]

In 1555 Salah Rais expelled the Spanish from Bejaïa.[73] Hasan Pasha vanquished Count Alcaudete's 12,000 men in Mostaganem three years later,[74] setting in stone the Ottoman control of North Africa.[75] This was followed by a failed attempt to take Oran in 1563,[76] in which the independent Kabylian kingdoms had significant involvement.[77]

The kingdom of Beni Abbas managed to maintain its independence, repelling the Ottomans in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbès then the Battle of Oued-el-Lhâm, and lasting until early 18th century.[78] Algiers had finally reached its 1830 borders towards the end of the 16th century.[79]

War against the Spanish-Moroccans

The Saadi dynasty of Morocco expanded eastward,[80] taking Tlemcen and Mostaganem and reaching the Chelif River.[71] These incursions into western Algeria resulted in the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551, where Hassan Pasha defeated the Moroccans and solidified Ottoman control of western Algeria.[71] This was followed by the Battle of Taza (1553) and the capture of Fez in 1554, in which Salah Rais defeated the Moroccan army, and conquered Morocco as far west as Fez, then put Ali Abu Hassun in place as ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[81] The Saadi ruler Mohammed al-Shaykh concluded an alliance with Spain, but his armies were again removed from Tlemcen in 1557.[82]

After the failed Ottoman Siege of Malta in 1565 and the Morisco revolt in 1568, beylerbey Uluç Ali marched on Tunis with 5300 Turks and 6000 Kabyle cavalry.[83] Uluç Ali defeated the Hafsid sultan at Béja, and conquered Tunis with few losses.[84] He then led the left wing of the corsair fleet in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and vanquished the Christian right wing of Andrea Doria and the Maltese Knights, saving what remained of the defeated Ottoman navy.[85]

Christian forces under the victor of Lepanto John of Austria were able to retake Tunis in 1573, leaving 8,000 men in the Spanish presidio of La Goletta.[86] But Uluç Ali reconquered Tunis in 1574.[87] With the capture of Fez in 1576, Caïd Ramdan, pasha of Algiers, put Abd al-Malik on the throne as an Ottoman vassal ruler of the Saadi Sultanate.[88][89]

During the rule of Uluç Ali's former subordinate Hassan Veneziano Pasha in the late 16th century, Algerian privateering ravaged the Mediterranean, reaching as far as the Canary Islands.[90] The waters from Valencia and Catalonia to Naples and Sicily were infested with Algerian pirate vessels.[91] Twenty-eight ships were captured near Málaga and 50 near the Gibraltar strait in a single season, and raiding Granada brought 4000 slaves to Algiers,[92] including Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes, whose time as a captive of Dragut inspired his novel Don Quixote.[93]

In 1578 Hassan Veneziano's troops ventured deep into the Sahara to Tuat in response to pleas from its inhabitants for help against Saadi-allied tribes from Tafilalt.[94][95] Kapudan Pasha Uluj Ali's campaign against Ahmad al-Mansur was cancelled in 1581;[90] Al-Mansur had at first vehemently refused subordination to Ottoman sultan Murad III, but sent an embassy to the Porte and signed a treaty that protected Moroccan de facto independence in exchange for annual tribute.[96] Nonetheless Figuig was Ottoman Algerian by 1584.[97]

17th century: Golden Age of Algiers

Algiers grew increasingly independent from Constantinople and engaged in widespread piracy in the 17th century in a period that became known as the "Golden age of Corsairs":[98] In the Mediterranean, the corsairs raided the Roman countryside, taking captives in Civitavecchia.[99] The expulsion of the Moriscos bolstered the corsairs with new sailors who painfully weakened Spain, ravaging its mainland and domains in Sicily and the islands of Italy, where people were taken captive en masse.[100]

Around 1600 they adopted the use of square-rigged sailing ships, which were introduced by Dutch renegade sailors such as Zymen Danseker[101] and began to rely less on Christian galley slaves.[102] These new vessels enabled the corsairs to sail far into the Atlantic Ocean, using speed and surprise of nearly a hundred well armed square-rigged ships based in Algiers to grow powerful in the Atlantic.[102] Exploring trade routes to India and America, the corsairs disrupted the commerce of all enemy nations. In 1619 the corsairs ravaged Madeira. Rais Mourad the younger plundered the coasts of Iceland in 1627, bringing 400 captives. The slave raid of Suðuroy took place in 1629, and in 1631, corsairs famously sacked Baltimore in Ireland, blocked the English Channel, and seized vessels in the North Sea.[103][104]

Algiers' port and navy grew and its population reached 100,000 to 125,000 in the 17th century,[105] due to its pirate economy of forced exchange and paid protection for the safety of crews, cargo and ships at sea.[106][107] The Maghrebi population became wealthy from selling seized ships and cargo through merchants in Genoa, Livorno, Amsterdam and Rotterdam.[99] and from ransoms paid for the release of prisoners captured on the high seas.[106] Homes and palaces were built with "the most precious objects and delicacies from the European and Eastern worlds".[98][108]

Ottoman suzerainty weakens

In the 16th century France signed capitulation treaties with the Ottomans, formalizing the Franco-Ottoman alliance.[109] In 1547, French trade rights and coral fishing were established in Algiers.[110] The French trade post in eastern Algeria, known as the Bastion of France, was taken over by the French "Lenche Company".[111] Believing it gave too many privileges to foreigners, Algiers disapproved of Constantinople's foreign policy.[112]

The authority of the pashas that the Sublime Porte appointed was not uncontested.[113] By the 1570s, the corsairs started to hunt European ships without taking heed of the alliances of Constantinople,[114] and the janissaries stationed in and paid by Algiers began to ignore the sultan and determine war strategy at their military council, known as the dîwân.[115] In clear defiance of the Ottoman treaty with France, Khider Pasha of Algiers, backed by the galleys of Murat Rais,[116] attacked the Bastion of France in 1604, then seized 6,000 sequins that Sultan Ahmed I had sent to French merchants to compensate for losses in the raid,[117] under the pretext of breaching agreements regarding wheat exports, tribute payments, and violation of good faith in trading with Moors.[111] The sultan ordered the new pasha Mohammed Koucha to have Khider Pasha strangled in 1605.[117]

The Porte renewed a treaty on 20 May 1605 that gave more privileges to France;[118] Clause 14 of the treaty authorized the French to use force against Algiers if the treaty was broken.[115] The French king Henry IV's envoy came to Algiers with a firman from the Porte ordering the French captives released and the Bastion rebuilt.[118] Mohammed Koucha Pasha agreed, but the janissaries revolted, imprisoned the Pasha and tortured him to death in 1606.[118] The dîwân refused to authorize the reconstruction of the Bastion, but agreed to release their French captives only on condition that Muslims detained in Marseilles also be released, a sign of how differently Algiers and Constantinople saw relations with France.[115][119]

Ali Bitchin Rais

The Barbary corsair captains, also known as the raïs, were represented by the tai'fa, or community of corsair captains. The captains were led by a Kapudan Rais (Admiral and Minister of Foreign affairs).[120] They became the dominant poltico-military power of early 17th century Algiers, and they provided most of the revenue of the regency through privateering.[121] This was due to a great influx of crewsmen: Moriscos expelled from Spain and European renegades.[121] Historian Jean-Baptiste Gramaye gave numbers of renegades who renounced their Christian faith between 1609 and 1619: 857 Germans, 138 Hamburgmen, 300 English, 130 Dutch and Flemings, 160 Danes, 250 Poles, Hungarians and Moscovites.[122] Their skills proved valuable for the strength of the Algerian fleet.[122]

Ali Bitchin Rais, a corsair of Italian origin,[123] became admiral and head of the tai'fa in 1621.[124] Immensely rich, He built a mosque and two palaces in Algiers, owned 500 slaves and married the daughter of the king of Kuku.[125] His power was clearly displayed in international treaties where he called himself "Governor and Captain general of the sea and land of Algiers".[126]

Ali Bitchin's raids on Spanish Italy brought thousands of slaves to Algiers.[127] In 1638 Sultan Murad IV called the corsairs up against the Republic of Venice. A storm forced their ships to shelter at Valona, but the Venetians attacked them there and destroyed part of their fleet. To their great anger, the sultan refused to compensate them for their losses, claiming they had not been in his service.[128][129] Sultan Ibrahim IV, also known as "Ibrahim the Mad", wanted to arrest Ali Bitchin for refusing to join the Cretan War, but the population rose up against him.[130] The diwân demanded that Ali Bitchin pay the janissaries their wages. So he took refuge in Kabylia for nearly a year, then returned in force to Algiers[130] to claim the title of pasha and demand from Sultan Mehmed IV 16,000 sultanis in exchange for 16 galleys.[131] The sultan appointed another pasha in 1645. When he arrived, Ali Bitchin suddenly died, possibly poisoned.[132][130]

Foreign policy

The Habsburg monarchy signed a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire in the early 17th century, ending the Long Turkish War, Algiers refused to abide by the capitulation treaties between Europe and Constantinople, however, prompting European powers to negotiate treaties directly with Algiers on commerce, tribute payments and slave ransoms.[112] in an acknowledgement of the autonomy of Algiers despite its formal subordination to the Sublime Porte.[133]

Algeria's foreign relations were governed by a militant Islam that believed in the superiority of the state over its opponents, demanding gifts and tribute and avoiding military setbacks that could bring religious protectionnism and territorial loss in favor of the European powers.[134] This was maintained by playing the adversaries of Algiers off against each other and avert any coalition that could pose a serious threat.[99][135][a] Thus, European nations at war with Algiers could not compete with shipping from nations at peace with it.[136] In fact, the lucrative cabotage business between Mediterranean ports required peaceful relations with Algiers,[137] prompting European vessels to carry passports issued by their diplomatic missions in Algiers to protect them from Algerian pirates.[112]

Algiers could not be at peace with all European states at the same time without weakening privateering; a religious, codified and strictly controlled form of warfare engaged by Algiers,[138][139] which kept revenues from naval spoils and tribute payments flowing to the treasury.[140] In this regard, a treaty with the Dutch in 1663 led to privateering against French vessels, then a treaty with France in 1670 prompted Algiers to break off relations with England and the Dutch.[141]

This conferred on Algerian foreign military elites an international legitimacy;[142][139] Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) noted that "Algiers exercised the jus ad bellum of a sovereign power through its corsairs".[143] This also gave them internal legitimacy as champions of jihad.[133]

Kingdom of France

France was the first European country to establish relations with Algiers.[140] They began direct negotiations in 1617 after more than 900 ships were taken and 8000 Frenchmen enslaved,[144] They reached an impasse however in part over two cannons Dutch corsair Simon Rais had taken with him to give to Charles, Duke of Guise when he left the Algerian navy in 1607.[145] A treaty was signed in 1619,[146] and another in 1628.[147][111] Algerians undertook to:[148][149]

- Respect France's vessels and coast

- Prohibit the sale of goods seized from French ships in their ports

- Allow French traders to safely live in Algiers

- Recognize and protect French concessions at the Bastion de France

- Allow trade in leather and wax.

Sanson Napollon, head of the Bastion de France, was able to supply Marseille with all the wheat it needed. In 1629 however, fifteen corsairs from an Algerian ship were massacred and the rest taken prisoner, causing the war to resume between Algiers and France.[150]

Napollon's death and suspecions of the Bastion supplying the French fleet encouraged the dîwân to decide that the French establishments should be terminated and "that the first to speak of them should lose his life", it declared. In 1637, Ali Bitchin razed the French Bastion, but a tribal revolt sparked in response.[151] In 1640, a new treaty returned to France its previous holdings in Africa, however, and the coral concession obtained the right to take security measures against raids,[151] in exchange for paying the pasha nearly 17,000 pounds.[145][152]

France was engulfed in the Fronde civil unrest by 1650, while the raïs operated off Marseilles and ravaged Corsica. But they had to face the French Levant Fleet and the Knights of Malta, who scored a minor victory against Algerian vessels near Cherchell in 1655. Cardinal Mazarin gave the order to reconnoitre the Algerian coasts with a view to a permanent installation.[115] First Minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert sent large forces to occupy Collo in the spring of 1663, but the expedition failed. In July 1664, King Louis XIV ordered another military campaign against Jijel, which took nearly three months and also ended in defeat.[153] France was forced to negotiate with Algiers and sign the 7 May 1666 agreement, stipulating the implementation of the 1628 treaty.[154][155] Louis XIV, who sought to have the French flag respected in the Mediterranean, ordered several intense bombing campaigns against Algiers from 1682 to 1688 in what is known as the Franco-Algerian war.[99] After fierce resistance led by Dey Hussein Mezzomorto, a conclusive peace treaty was finally signed.[156]

Kingdom of England

English admiral Robert Mansell led an expedition in 1621 that sent fireships (burning ships) into the fleet moored in Algiers, but it failed and Mansell was recalled to England on 24 May 1621.[157] James I negotiated directly with the pasha of Algiers [147][158] in 1622 but more than 3000 Englishmen remained enslaved in Algiers. A fleet under Admiral Blake managed to sink several Tunisian ships, which convinced Algiers to sign a peace treaty with Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.[159] England introduced a series of anti-counterfeiting and mandatory "Algerian passports" on southbound merchant ships to guarantee each ship's authentic registry to Algerian pirate vessels.[160] Fighting with a combined Anglo-Dutch force in 1670 cost Algiers several ships and 2200 sailors near Cape Spartel, and English ships burned seven other ships in Béjaïa. A regime change in Algiers ensued.[161]

From 1674 to 1681 Algiers captured around 350 ships and 3000 to 5000 slaves.[162][163] But since the French were also attacking them, they signed a peace treaty with Charles II on 10 April 1682 where he recognised that his subjects were slaves in Algiers.[163]

Dutch Republic

The English peace treaty with Algiers affected Dutch shipping. Merchants arriving at The Hague all indicated that the Dutch were losing trade to the English.[164][165] From 1661 to 1664, the Dutch sent Michiel de Ruyter and Cornelis Tromp on several expeditions to Algiers in an attempt to make the Algerians accept the free ships, free goods principle.[166][165] Although the Algerians had accepted the principle in 1663, they went back on their agreement the following year. De Ruyter was again dispatched to Algiers, but the beginning of hostilities with England, leading up to the Second Anglo-Dutch War, cut his mission short.[167]

A peace agreement signed in 1679 was the result of four years of negotiations, and until 1686, precariously maintained a peace for Dutch trade with southern Europe,[168][165] at the price of tribute to Algiers in the form of cannons, gunpowder and naval stores, which France and England both condemned.[169] But peace did not last. Between 1714 and 1720, 40 ships were captured, and their seamen taken captive.[170]

After lengthy negotiations and several military expeditions, the Dutch finally achieved peace.[170] The new Dutch consul in Algiers, Ludwig Hameken, asked for a Mediterranean pass,[171] and agreed to pay a yearly tribute for the next century. The Anglo-Spanish War (1727–1729) distracted the British from their trade rivalries, and the Dutch managed to provide stiff competition. When the war ended however, British shipping again flourished in the Mediterranean, and Dutch trade fell off.[171]

Maghrebi wars (1678–1756)

Algeria's relations with other Maghreb countries were troubled most of the time,[172] for several historical reasons.[79] Algiers considered Tunisia a dependency because it had annexed it to the Ottoman Empire, which made the appointment of its pashas a prerogative of the Algerian beylerbeys.[173] Tunis had inherited ambitions in the Constantine region from the Hafsid era, and rejected Algerian suzerainty. Morocco opposed the Ottomans with determination, and saw Algiers as a danger to its independence. It also had ancient ambitions in western Algeria and especially in Tlemcen.[172]

Both states also supported rebellions in Algiers. In 1692 inhabitants of the capital and neighboring tribes tried to depose the Ottomans while Dey Hadj Chabane was campaigning in Morocco. They set fire to several buildings and some of the ships at anchor there.[174]

Tunisian campaigns

Tunis adamantly refused subordination to Algeria. Beginning in 1590, the diwân of Tunisian janissaries revolted against Algiers, and the country became a vassal of Constantinople itself.[172] A peace treaty concluded on 17 May 1628, following an Algerian victory was devoted to the delimitation of the borders between them.[175] In 1675, Murad II Bey of Tunis died. This unleashed a twenty-year civil war between his sons.[176] Dey Chabane took this opportunity to defeat the Tunisians in the Battle of Kef, conquer Tunis and depose Mohamed Bey El Mouradi in 1694, replacing him with puppet ruler Ahmed ben Tcherkes. Hadj Chabane went back to Algiers with heavy booty, including cannons, slaves, and 120 mules loaded with gold.[177] Fed up with this situation, Tunisians revolted. Unwilling to make another campaign against Tunis, the janissaries mutinied, tortured Hadj Chabane and executed him on 15 August 1695.[178]

After he signed an alliance with the sultan of Morocco Moulay Ismail, Murad III Bey of Tunis started the Maghrebi war in 1700.[79] He took Constantine before Algiers regained the upper hand in the Battle of Jouami' al-Ulama.[79] Ibrahim Cherif, the Agha of the Tunisian sipahi cavalry, put an end to the Muradid regime and was named Dey by the militia and pasha and by the Ottoman sultan.[179] However, he did not manage to put an end to the Algerian and Tripolitan incursions. Finally defeated near Kef by the Dey of Algiers on 8 July 1705, he was captured and taken to Algiers.[180] By this time, Hussein I ibn Ali Bey founded the Husainid dynasty of Tunis. After a failed revolt, Abu l-Hasan Ali I Pasha took refuge in Algiers, where he managed to gain the support of Dey Ibrahim Pasha.[181] Hassan Bey of Constantine sent a force of 7,000 men led by Danish slave Hark Olufs to invade Tunis in 1735 and installed bey Ali I Pasha,[182] as a vassal of Algiers, who promised an annual tribute to the dey.[182][183]

In another campaign directed against Tunis in 1756,[184] Ali I Pasha was deposed and brought to Algiers in chains, then strangled by supporters of his cousin and successor Muhammad I ar-Rashid on 22 September. Tunis became a tributary of Algiers, recognized its suzerainty for 50 years, and agreed to send enough olive oil to light the mosques of Algiers every year.[185][186]

Moroccan campaigns

In 1678, Moulay Ismail mounted an expedition to Tlemcen. He assembled his contingents on the Upper Moulouya, joined by the tribes of Orania, and advanced to the Chelif region to give battle there.[187] The Ottoman Algerians brought in artillery, and routed the Moroccans. Negotiations with Dey Chabane fixed the border at the Moulouya, where it remained throughout the Saadian period.[188] In 1691, Moulay Ismail launched a new offensive against Orania, and Dey Chabane, supported by 10,000 janissaries and 3,000 Zwawa infantry,[189] killed 5,000 and routed the rest of the attackers on the Moulouya before marching on Fez.[190] But Moulay Ismail surrendered. According to French historian Henri de Grammont: "He presented himself before the winner with his hands bound, and while kissing the ground three times, he said to him: You are the knife, and I the flesh that you can cut."[191][174] He agreed to pay tribute and sign the treaty of Oujda which confirmed the Moulouya river border.[192] In 1694, the Ottoman sultan invited that of Morocco to cease his attacks against Algiers.[188]

In 1700, after coming to an agreement with the Tunisian Muradids to simultaneously attack Constantine, the Moroccan sovereign launched a new expedition against Orania with an army composed mostly of Black Guards.[193] But Moulay Ismail's 60,000 men were beaten again at the Chelif river by Dey Hadj Mustapha.[194][195] Following these expeditions, Hadj Moustapha wrote to Moulay Ismaïl about the attachment of the Algerians and their territory to the power of the Regency of Algiers.[196] Moulay Ismail made one last attempt to capture Oran in 1707, but his army was almost entirely destroyed,[197][198] which ended his projects of expansion towards Orania.[199] In the following years, Moulay Ismaïl led Saharan incursions towards Aïn Madhi and Laghouat without succeeding in settling them permanently.[195]

Dey Muhammad ben Othman Pasha (1766–1792)

Algerian Dey Baba Ali Chaouch ended Ottoman influance by taking the Pasha title for himself in 1710.[200] When Austria concluded the peace of Passarowitz with the Ottoman Empire in 1718, Dey Ali Chaouch had Austrian ships captured despite the treaty and refused to pay compensation to an Ottoman-Austrian delegation,[201] thus confirming the independent foreign policy of Algiers[202] despite its nominal subordination to the Ottoman Empire.[201]

In 3 February 1748 Dey Mohamed Ibn Bekir issued what is known as "The Fundamental Pact of 1748" or "Pact of trust", a fundamental politico-military text that defined the rights of the subjects of the dey of Algiers and of all the inhabitants living in the regency of Algiers. It codified the behavior of the different army compositions: Janissaries, Gunners, Chaouchs and Spahis.[203]

Muhammad ben Othman Pasha became dey in 1766 as his predecessor Dey Ali Bousbaa had wished. He ruled over a powerful and prosperous Algiers for a full quarter-century until he died in 1791.[110][204] He was a "rational, courageous, and determined man who adhered to working according to Islamic law, loved jihad, was austere even with regard to public treasury funds", according to the memoirs of Ahmad Sharif al-Zahhar, a naqib al-ashraf of Algiers in its late Ottoman era.[205] He succeessfully handled most of the problems he faced during his rule, especially Spanish and Portuguese raids. He fortified Algiers with a number of forts and towers,[206] such as the Borj Sardinah, Borj Djedid, and Borj Ras Ammar, and repaired the Sayyida mosque next to Jenina Palace, which had been damaged by Spanish bombardment. He brought water to the city, and supplied it to all the castles, towers, fortresses, and mosques. He also built springs in the center of the city for people to drink from, and set up a special financial reserve to take care of and maintain the water supply from these streams.[205]

As dey, Muhammad ben Othman Pasha kept the janissaries in check, developed trade,[204] secured regular tribute payments from European states,[204][140] strengthened the Algerian fleet and supplied it with men, weapons, and ships. Several captains became famous during his reign, such as Rais Hamidou, Rais Haj Suleiman, Rais Ibn Yunus and Rais Hajj Muhammad, who according to Al-Zahar commanded about 24,000 men in his various maritime incursions.[207]

Pacification of the Regency

Muhammad Othman started his reign by leading campaigns against the tribes of Felissa in Kabylia, which were in constant rebellion. A first attempt in 1767 ended in failure and the tribes managed to reach the gates of Algiers itself. Nine years later however, the dey surrounded them in their mountains and made their leaders submit.[208] The eastern Salah Bey ben Mostefa of Constantine launched several expeditions south. In 1785, he marched through the Amour Range, then stormed Aïn Beida and Aïn Madhi, and occupied all of Laghouat. He then received tribute from the Ibadi community of the south. In 1789, Salah bey occupied the city of Touggourt, appointed Ben-Gana as "Sheikh of the Arabs" and imposed heavy tribute on the Berber Banu Djellab dynasty there.[209]

War with Denmark

Dey Muhammad Othman Pasha increased the annual royalties paid by the Netherlands, Venice, Sweden and Denmark. They accepted, except for Denmark, which assigned Frederick Kaas to lead four ships of the line, two bomb galiots and two frigates, against the city of Algiers in 1770. The bombardment ended in failure.[210] Shortly after, Algerian pirates attacked Dano-Norwegian ships for a whole year.[211] Denmark submitted to the dey's conditions and agreed to pay 2.5 million dollars in compensation for the damage to the city, and provide 44 cannons, 500 quintals of gunpowder, and 50 sails. It also agreed to ransom its captives and pay royalties every two years with various gifts to statesmen.[212]

War with Spain

The War of the Spanish Succession, gave western bey Mustapha Bouchelaghem the opportunity to capture Oran and Mers-el Kebir in 1708,[213] but he lost them back in 1732 to a successful campaign by the Duke of Montemar.[214] In 1775 Irish-born admiral of the Spanish Empire Alejandro O'Reilly led an expedition to knock down pirate activity in the Mediterranean. The assault's spectacular failure dealt a humiliating blow to the Spanish military reorganisation.[215]

From 1–9 August 1783 a Spanish squadron of 25 ships bombarded Algiers, but could not overcome its defenses. A Spanish squadron of four ships of the line and six frigates inflicted no significant damage on the city and had to withdraw from its guns.[216] The commander of this fleet and that of 1784 was Spanish admiral Antonio Barceló. A European league of 130 ships from the Spanish Empire, Kingdom of Portugal, Republic of Venice and Order of Saint John of Jerusalem bombarded Algiers on 12 July 1784. This failed, and the Spanish squadron fell back from the city's defenses.[217] Dey Mohamed ben-Osman asked for a 1,000,000 pesos to conclude a peace in 1785. Negotiations (1785–87) followed for a lasting peace between Algiers and Madrid.[218]

After a massive earthquake in 1790, the reconquest of Oran and Mers El Kébir began.[219][140] Oran was a concern for the 18th-century Spanish, torn between the competing imperatives of preserving their presidio and maintaining a fragile peace with Algiers.[218] After the death of Mohamed ben Othman, his khaznagy (vizier) qnd adopted son Sidi Hassan was elected dey and negotiations with Count Floridablanca resumed. The resulting Spanish-Algerian Peace Treaty of 1791 ended almost 300 years of war. Mers-el-Kebir and Oran once again rejoined Algeria, and Spain undertook to "freely and voluntarily" return two cities in exchange for the exclusive right to trade certain agricultural products in Oran and Mers-el-Kébir. On 12 February 1792, Spanish soldiers left Oran and Mohammed el Kebir entered the city. Algerians had freed their land from foreign occupation.[220][221]

Decline of Algiers (1800–1830)

Algerian Jewish merchants

The Jews of Algiers became an economic power and eliminated many European merchant houses from the Mediterranean, which deeply worried the Marseillais defending their threatened monopoly.[b] French consuls resented the Jews, and urged their King to pass ordinances to prevent them from trading in French harbors. But the Jewish merchants dealt in prize goods from the corsairs as well as in more regular merchandise, and were essential to government because of their contacts and skill in aligning their affairs with the interests of the Algerian state.[222] They were at the origin of various Algerian disputes with Spain and especially with France.[222][223]

To avoid further difficulty, the French king established rules, port regulations, and tariffs to make good the losses of the French. These prevented Algerian merchants from trading in French ports and transporting their cargoes of wax, wheat and honey to the French market themselves.[222] The Marseillais wanted to prohibit Algerian Jews from remaining more than three days in port, and appealed to the dey to prohibit Jews from trading in Marseilles. Muslim merchants had a cemetery in Marseilles and wanted to build a mosque there, but were refused. Moreover, the raïs, especially the Christian converts to Islam, did not dare land on Christian soil, where they risked imprisonment and torture.[224]

Unable to own commercial vessels or to transport their goods themselves to Europe, the Algerians used foreign intermediaries and fell back again on the corso to compensate them.[224]

Crisis of the 19th century

During Napoleon's campaign in Egypt, Algiers supplied the French army with wheat in large quantities.[225] In the early 19th century, Algiers was struck with political turmoil and economic stress.[226] Between 1803 and 1805, famine caused by failed wheat harvests resulted in public riots[226] that led to the death of prominent Jewish grain merchant Naphtali Busnash who was blamed for the shortages. Dey Mustapha Pasha's assassination followed, despite encouraging an anti-Jewish pogrom, which began a 20-year period of coups,[226] in which seven deys perished.[227]

In 1792 popular administrator of the Beylik of Constantine Saleh Bey was killed by order of the dey, a loss to Algiers of a seasoned politician and military and administrative leader.[228] This engulfed the once most prosperous Beylik of the regency[229] into a period of anarchy and disorder, as 17 beys succeeded in office from 1792 to 1826, most of whom were incompetent.[230] At the start of the 19th century, intrigues at the Moroccan court in Fez inspired the Zawiyas to stir up unrest and revolt.[231] Muhammad ibn Al-Ahrash, a marabout from Morocco and leader of the Darqawiyyah-Shadhili religious order, led the revolt in Constantinois with his Rahmaniyya allies.[232] The Darqawis in western Algeria joined the revolt and besieged Tlemcen, and the Tijanis also joined the revolt in the south. But the revolt was defeated by Bey Osman, and he himself was killed by Dey Hadj Ali.[233] Morocco took possession of Figuig in 1805, then Tuat and Oujda in 1808,[234][235][236] and Tunisia freed itself from Algeria after the wars of 1807 and 1813.[237]

Constant war burdened the population with heavy taxes and fines that took no account of the hardship they caused. This burden primed the population to respond to calls for disobedience, which the deys always met with brute force.[238] This instability led to a decline in revenues, preventing the janissaries' ordinary pay to meet their demands, which caused discontent, mutinies and military setbacks, in addition to the janissaries' objection to reforms that threatened their privileges. This paralyzed the government of the regency.[227] Destructive earthquakes, epidemics and a drought in 1814 led to the death of thousands and a decline in trade.[239]

Barbary Wars

Internal fiscal problems in the early 19th century led Algiers to again engage in widespread piracy against American and European shipping, taking full advantage of the Napoleonic Wars.[240] Being the most notorious Barbary state,[241][242] and willing to curb American trade in the Mediterranean, Algiers declared war on the U.S in 1785 on the pretext of asserting its rights to search and seizure in the absence of a treaty with a given nation.[243] It captured 11 American ships and enslaved 100 sailors. In 1797 Rais Hamidou captured 16 Portuguese ships and 118 prisoners.[244] The U.S. agreed to buy peace with Algiers in 1795 for $10 million including ransoms and annual tribute over 12 years.[240] Another treaty with Portugal in 1812 brought $690,337 in ransom and $500,000 in tribute.[245] But Algiers was defeated in the Second Barbary War when U.S. admiral Stephen Decatur captured the Algerian flagship "Mashouda" in the battle off Cape Gata, killing Rais Hamidou on 17 June 1815.[246] Decatur went to Algiers and imposed war reparations on the dey and the immidiate cease of paying tribute to him on 29 June 1815.[246]

The new European order that arose from the French Revolutionary Wars and the Congress of Vienna no longer tolerated Algerian piracy, deeming it as "barbarous relic of a previous age".[247] This culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers,[248] ending in a victory for the British and Dutch, a weakened Algerian navy, and liberation of 1200 slaves.[249]

Following this defeat dey Omar Agha managed to restore the defenses of Algiers,[250] and some European nations already agreed to pay tribute again, but he was eventually killed.[251] To stabilize the state, his successor Ali Khodja suppressed insubordinate elements of the Odjak with the help of Koulouglis and Zwawa soldiers.[247][252] The last dey of Algiers Hussein Pasha sought to nullify the consequences of earlier Algerian defeats by restarting piracy again, and withstanding a fruitless British attack on Algiers in 1824 led by Vice-Admiral Harry Burrard Neale.[253] This cemented a false belief that Algiers could still fight off a disunited Europe.[254]

French invasion

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers greatly benefited from Mediterranean trade and massive food imports by France, largely bought on credit. In 1827, Hussein Dey demanded that the restored Kingdom of France pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 for supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.[255]

The answers of French consul Pierre Deval displeased Hussein Dey, who hit him with a fan. King Charles X used this incident as an excuse to break ties[255] and start a full-scale invasion of Algeria. The French military landed on 14 June 1830. Algiers surrendered on 5 July, and Hussein Dey went into exile in Naples.[107] Charles X was overthrown a few weeks later by the July Revolution and replaced by his cousin, Louis Philippe I.[255]

Notes

- ^ William Spencer notes: "For three centuries, Algerine foreign relations were conducted in such a manner as to preserve and advance the state's interests in total indifference to the actions of its adversaries, and to enhance Ottoman interests in the process. Algerine foreign policy was flexible, imaginative, and subtle; it blended an absolute conviction of naval superiority and belief in the permanence of the state as a vital cog in the political community of Islam, with a profound understanding of the fears, ambitions, and rivalries of Christian Europe." (Spencer (1976) pp. xi)

- ^ The Chamber of Commerce of Marseilles complained in a memoir in 1783: "Everything announces that this trade will one day imperceptibly be of some consideration, because the country has by itself a capital fund which has given the awakening to the peoples who live there, and that nothing is so common today, to see Algerians and Jews domiciled in Algiers coming to Marseilles to bring us the products of this kingdom." (Kaddache (2003) p. 538)

References

- ^ Julien 1970, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Devereux 2024, p. 73.

- ^ Pitcher 1972, p. 107.

- ^ Al-Madani 1965, pp. 64–71.

- ^ Liang 2011, p. 142.

- ^ Julien 1970, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Ruedy 2005, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, p. 147.

- ^ Garcés 2002, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Hess 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Wolf 1979, p. 8.

- ^ a b Hess 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Brill 1987, p. 258.

- ^ McDougall 2017, p. 10.

- ^ Brill 1987, p. 471.

- ^ Gaïd 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Kaddache 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, p. 149.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, p. 40.

- ^ Al-Madani 1965, p. 175.

- ^ Garrot 1910, p. 360.

- ^ a b c Hess 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Spencer 1976, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Al-Madani 1965, pp. 184–186.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 19.

- ^ a b Garrot 1910, p. 362.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 9.

- ^ Hess 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Spencer 1976, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Kaddache 2003, p. 335.

- ^ a b Merouche 2007, pp. 90–94.

- ^ Imber 2019, p. 209.

- ^ Vatin 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Vatin 2012, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Panzac 2005, p. 1.

- ^ a b Julien 1970, p. 281.

- ^ a b c Hess 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Gaïd 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Gaïd 2014, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Holt et al. 1970, p. 250.

- ^ a b Kaddache 2003, p. 336.

- ^ Hess 2011, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Hugh 2014, p. 154.

- ^ a b Hess 2011, p. 68.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 25.

- ^ Naylor 2015, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Crowley 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Servantie 2021, p. 90.

- ^ Everett 2010, p. 55.

- ^ a b Ward, Prothero & Leathes 1905, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Al-Jilali 1994, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Everett 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, p. 160.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, p. 151.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 27.

- ^ a b Hess 2011, p. 74.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, pp. 153–155.

- ^ a b Jamieson 2013, p. 25.

- ^ a b Crowley 2009, p. 73.

- ^ Garcés 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Kaddache 2003, p. 386.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 27.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 29.

- ^ Hugh 2014, p. 191.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 296.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 252.

- ^ a b Gaïd 1978, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Julien 1970, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 71.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 52.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 89.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 56.

- ^ Hugh 2014, p. 195.

- ^ Gaïd 1978, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Julien 1970, p. 319.

- ^ Chenntouf 1999, p. 188.

- ^ Levtzion 1975, p. 406.

- ^ Abun Nasr 1987, pp. 157–158.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Hess 2011, p. 89.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Hess 2011, p. 93.

- ^ Truxillo 2012, p. 73.

- ^ Levtzion 1975, p. 408.

- ^ Hugh 2014, p. 196.

- ^ a b Julien 1970, p. 301.

- ^ BRAUDEL 1990, pp. 882–883.

- ^ BRAUDEL 1990, p. 881.

- ^ Garcés 2002, p. 205.

- ^ Bellil 1999, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Abitbol 1979, p. 48.

- ^ Cory 2016, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Hess 2011, p. 116.

- ^ a b Crawford 2012, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d Kaddache 2003, p. 416.

- ^ Lowenheim 2009, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 75.

- ^ a b BRAUDEL 1990, p. 885.

- ^ Garrot 1910, p. 383.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, pp. 75–131.

- ^ Naylor 2015, p. 121.

- ^ a b Clancy-Smith 2003, p. 420.

- ^ a b Bosworth 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 200.

- ^ Panzac 2005, p. 25 , 27.

- ^ a b McDougall 2017, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Julien 1970, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Maameri 2008, pp. 108–142.

- ^ Boyer 1973, p. 162.

- ^ Burman 2022, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d Kaddache 2003, p. 401.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 181.

- ^ a b Garrot 1910, pp. 444.

- ^ a b c Garrot 1910, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Léon 1843, p. 219.

- ^ Konstam 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b Atsushi 2018, pp. 25–28.

- ^ a b Spencer 1976, p. 127.

- ^ Egilsson 2018, p. 218.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 227.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 178.

- ^ Atsushi 2018, pp. 31.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 183.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 100.

- ^ Stevens 1797, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Jamieson 2013, p. 101.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 194.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 237.

- ^ a b Koskenniemi, Walter & Fonseca 2017, p. 203-204.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 129.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 118.

- ^ Greene 2010, p. 122.

- ^ Panzac 2020, pp. 22–25.

- ^ E. Tucker 2019, pp. 132–137.

- ^ a b Panzac 2005, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Panzac 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 315.

- ^ Atsushi 2018, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Koskenniemi, Walter & Fonseca 2017, p. 205.

- ^ Monson 1902, p. 101.

- ^ a b de Grammont 1879–1885.

- ^ Rouard De Card 1906, pp. 11–15.

- ^ a b Panzac 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Plantet 1894, p. 3.

- ^ Rouard De Card 1906, p. 15.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 213.

- ^ a b Julien 1970, p. 313.

- ^ Rouard De Card 1906, p. 22.

- ^ Léon 1843, p. 226.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Rouard De Card 1906, p. 32.

- ^ Jörg 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Matar 2000, p. 150.

- ^ Maameri 2008, p. 116.

- ^ Wolf 1979, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Fisher 1957, pp. 230–239.

- ^ Panzac 2005, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Coffman et al. 2014, p. 177.

- ^ a b Murray (Firm) 1874, p. 57.

- ^ Panzac 2020, pp. 178–183.

- ^ a b c Ressel 2015.

- ^ Brandt 1907, pp. 141–269.

- ^ Blok 1928, p. 185 & 190 & 198.

- ^ Krieken 2002, pp. 50–55.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 146.

- ^ a b Wolf 1979, pp. 309–311.

- ^ a b Ressel 2015, pp. 237–255.

- ^ a b c Boaziz 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 50.

- ^ a b de Grammont 1887, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Chenntouf 1999, p. 205.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 305.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 265.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 266.

- ^ Garrot 1910, p. 555.

- ^ Brill 1987, p. 854.

- ^ Barrie 1987, p. 25.

- ^ a b de Grammont 1887, p. 295.

- ^ Gaïd 1978, p. 31.

- ^ Anderson 2014, p. 256.

- ^ Cornevin 1962, p. 405.

- ^ Panzac 2005, p. 300.

- ^ Garrot 1910, p. 511.

- ^ a b Kaddache 2003, p. 414.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 313.

- ^ Tassy 1725, p. 301.

- ^ Léon 1843, p. 234.

- ^ Chenntouf 1999, p. 204.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 280.

- ^ Turbet-Delof 1973, p. 189.

- ^ a b Abitbol 2014, p. 631.

- ^ El Adnani 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Daumas & Yver 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Playfair 1891, p. 179.

- ^ Kaddache 2003, p. 415.

- ^ Saidouni 2009, p. 195.

- ^ a b Masters 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 122.

- ^ Société historique algérienne (1860). Revue africaine (in French). La Société. pp. 211–219.

- ^ a b c Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 278.

- ^ a b Zahhār 1974, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Saidouni 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 70.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, p. 236.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Jamieson 2013, p. 181.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 71.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, p. 240.

- ^ Al-Madani 1965, pp. 461–462.

- ^ Al-Madani 1965, p. 481.

- ^ Spencer 1976, pp. 132–135.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 135.

- ^ de Grammont 1887, p. 328.

- ^ a b Terki Hassaine 2004, pp. 197–222.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 306.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 307.

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1970, p. 279.

- ^ a b c Wolf 1979, p. 318.

- ^ Panzac 2005, pp. 234–237.

- ^ a b Kaddache 2003, p. 538.

- ^ Courtinat 2003, p. 139.

- ^ a b c McDougall 2017, p. 46.

- ^ a b Panzac 2005, p. 296.

- ^ Siari Tengour 1998, pp. 71–89.

- ^ Ruedy 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Brill 1987, p. 866.

- ^ Martin 2003, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 326.

- ^ Mercier 1903, pp. 308–319.

- ^ Al-Jilali 1994, p. 308.

- ^ Brill 1987, p. 947.

- ^ Saidouni 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Mercier 1888, p. 468.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 320.

- ^ a b Rinehart 1985, p. 27.

- ^ Lowenheim 2009, p. 83.

- ^ Atanassow 2022, p. 131.

- ^ Spencer 1976, pp. 136.

- ^ Boaziz 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Spencer 1976, pp. 136–139.

- ^ a b Panzac 2005, p. 270.

- ^ a b McDougall 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Panzac 2005, pp. 284–292.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 331.

- ^ Spencer 1976, p. 144.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 332.

- ^ Julien 1970, p. 332.

- ^ Lange 2024, p. 163.

- ^ Wolf 1979, p. 333.

- ^ a b c Meredith 2014, p. 216.

Bibliography

- Abitbol, Michel (2014). Histoire du Maroc. EDI8. ISBN 978-2-262-03816-8. OCLC 1153447202.

- Abun Nasr, Jamil M. (1987). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33767-0. OCLC 951299985.

- Abitbol, Michel (1979). Tombouctou et les Arma: de la conquête marocaine du Soudan nigérien en 1591 à l'hégémonie de l'empire Peulh du Macina en 1833 [Timbuktu and the Arma: from the Moroccan conquest of Nigerien Sudan in 1591 to the hegemony of the Fulani empire of Macina in 1833] (in French). G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-0770-1.

- الجيلالي [Al-Jilali], عبد الرحمن [Abdul Rahman] (1994). تاريخ الجزائر العام للعلامة عبد الرحمن الجيلالي الجزء الثالث: الخاص بالفترة بين 1514 إلى 1830م [The General History of Algeria by Abd al-Rahman al-Jilali, Part Three: Concerning the period between 1514 and 1830 AD] (in Arabic). Algiers: الشركة الوطنية للنشر والتوزيع [National Publishing and Distribution Company].

- المدنى [Al-Madani], أحمد توفيق [Ahmed Tawfiq] (1965). كتاب حرب الثلاثمائة سنة بين الجزائر واسبانيا 1492– 1792 [The Three Hundred Years' War between Algeria and Spain 1492 – 1792] (in Arabic). Algeria: الشركة الوطنية للنشر والتوزيع [National Publishing and Distribution Company]. OCLC 917378646.

- Anderson, M. S. (2014). Europe in the Eighteenth Century 1713-1789. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87965-7. OCLC 884647762.

- Atanassow, Ewa (2022). Tocqueville's Dilemmas, and Ours: Sovereignty, Nationalism, Globalization. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22846-4.

- Atsushi, Ota (2018). In the Name of the Battle against Piracy: Ideas and Practices in State Monopoly of Maritime Violence in Europe and Asia in the Period of Transition. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-36148-5.

- Barrie, Larry Allen (1987). A Family Odyssey: The Bayrams of Tunis, 1756-1861. Boston University.

- Bellil, Rachid (1999). Les oasis du Gourara (Sahara algérien) [The oases of Gourara (Algerian Sahara)] (in French). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0721-8.

- Blok, P.J. (1928). Michiel de Ruyter (PDF) (in Dutch). Martinus Nijhof.

- بوعزيز [Boaziz], يحيى [Yahya] (2007). الموجز في تاريخ الجزائر - الجزء الثاني [Brief history of Algeria - Part Two] (in Arabic). Algeria: ديوان المطبوعات الجامعية [University Publications Office]. ISBN 978-9961-0-1045-7. OCLC 949595451.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. OCLC 231801473. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Boyer, Pierre (1973). "La révolution dite des "Aghas" dans la régence d'Alger (1659-1671)" [The "Agha" revolution in the Regency of Algiers]. Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 13 (1): 168–169. doi:10.3406/remmm.1973.1200.

- Brandt, Geeraert (1907). Uit het leven en bedrijf van den heere Michiel de Ruiter... [From the life and business of Mr. Michiel de Ruiter] (in Dutch). G. Schreuders.

- BRAUDEL, FERNAND (1990). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Vol. 2. Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2-253-06169-7. OCLC 949786917.

- Brill, E.J. (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Vol. 1. Aaron - BABA BEG. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-09787-2. OCLC 612244259.

- Burman, Thomas E. (2022). The Sea in the Middle: The Mediterranean World, 650–1650. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-96900-1. OCLC 1330935035.

- Chenntouf, Tayeb (1999). "La dynamique de la frontière au Maghreb", Des frontières en Afrique du xiie au xxe siècle [The dynamic of the Maghreb frontier: African frontiers from the 12th to the 20th century] (PDF). UNESCO.

- Clancy-Smith, Julia (2003). "Maghrib". In Mokyr, Joel (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510507-0. OCLC 52121385.

- Cornevin, Robert (1962). Histoire de L'Afrique: L'Afrique précoloniale, 1500-1900 [History of Africa: Pre-colonial Africa, 1500 to 1900] (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-11470-7. OCLC 1601772.

- Crawford, Michael H (2012). Causes and Consequences of Human Migration: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01286-8. OCLC 1332475393.

- Crowley, Roger (2009). Empires of the Sea: The Final Battle for the Mediterranean, 1521-1580. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-25080-6. OCLC 903372707.

- Coffman, D'Maris; Leonard, Adrian; O'Reilly, William (2014). The Atlantic World. Routledge worlds. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-57605-1. OCLC 896126433.

- Cory, Stephen (2016). Reviving the Islamic Caliphate in Early Modern Morocco. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-06343-8. OCLC 1011199413.

- Courtinat, Roland (2003). La piraterie barbaresque en Méditerranée: XVI-XIXe siècle [Barbary piracy in the Mediterranean: 16th-19th century] (in French). Nice: Gandini. ISBN 978-2-906431-65-2. OCLC 470222484.

- Daumas, Eugène; Yver, Georges (2008). Les correspondances du Capitaine Daumas, consul de france à Mascara: 1837-1839 (in French). Editions el Maarifa. p. 102. ISBN 978-9961-48-533-0. OCLC 390564914.

- Devereux, Andrew W. (2024). "Spanish imperial expansion, ca. 1450–1600". In Dowling, Andrew (ed.). The Routledge handbook of Spanish history (1st ed.). London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-032-11189-6. OCLC 1085348412.

- de Grammont, Henri Delmas (1887). Histoire d'Alger sous la domination turque. Paris: E. Leroux. OCLC 1041890171.

- de Grammont, Henri Delmas (1879–1885). Relations entre la France et la Régence d'Alger au XVIIe siècle ,La Mission de Sanson Napollon (1628-1633). Les Deux canons de Simon Dansa (1606–1628) [Relations between France and the Regency of Algiers in the 17th century, The Mission of Sanson Napollon (1628–1633)] (in French). Algiers: A. Jourdan. OCLC 23234894.

- El Adnani, Jillali (2007). La Tijâniyya, 1781-1881: les origines d'une confrérie religieuse au Maghreb [La Tijâniyya, 1781-1881: the origins of a religious brotherhood in the Maghreb]. Rabat: Marsam. ISBN 978-9954-21-084-0. OCLC 183890167.

- Egilsson, Ólafur (2018). The Travels of Reverend Ólafur Egilsson: The Story of the Barbary Corsair Raid on Iceland in 1627. Catholic University of America Press + ORM. ISBN 978-0-8132-2870-9. OCLC 1129454284.

- E. Tucker, Judith (2019). The Making of the Modern Mediterranean: Views from the South. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-30460-4. OCLC 1055262696.

- Everett, Jenkins Jr (2010). The Muslim Diaspora: A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. Vol. 2, 1500–1799. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4689-6. OCLC 1058038670.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1975). "The Western Maghrib and Sudan". In Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland (eds.). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6. OCLC 165455782.

- Fisher, Godfrey (1957). Barbary Legend; War, Trade, and Piracy in North Africa, 1415-1830. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-7617-8. OCLC 310710099.

- Gaïd, Mouloud (2014) [1975]. L'Algérie sous les Turcs [Algeria under the Turks] (in French). Mimouni. ISBN 978-9961-68-157-2. OCLC 1290162902.

- Gaïd, Mouloud (1978). Chronique des beys de Constantine [Chronicle of the beys of Constantine] (in French). Office des publications universitaires. OCLC 838162771.

- Garcés, María Antonia (2002). Cervantes in Algiers: A Captive's Tale. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1470-7. OCLC 61463931.

- Garrot, Henri (1910). Histoire générale de l'Algérie [General history of Algeria] (in French). Algiers: P. Crescenzo. OCLC 988183238.

- Greene, Molly (2010). Catholic Pirates and Greek Merchants: A Maritime History of the Early Modern Mediterranean. Princeton modern Greek studies. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14197-8. OCLC 1049974791.

- Hess, Andrew C (2011). The Forgotten Frontier: A History of the Sixteenth-Century Ibero-African Frontier. Publications of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. 10. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-33030-3. OCLC 781318862.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1970). The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2A. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. OCLC 921054380.

- Hugh, Roberts (2014). Berber Government: The Kabyle Polity in Pre-colonial Algeria. Library of Middle East history. Vol. 14. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-251-6. OCLC 150379130.

- Imber, Colin (2019). The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The Structure of Power (3 ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1350307629.

- Jamieson, Alan G. (2013). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0. OCLC 828423804.

- Jörg, Manfred Mössner (2013). Die Völkerrechtspersönlichkeit und die Völkerrechtspraxis der Barbareskenstaaten: (Algier, Tripolis, Tunis 1518-1830). Neue Kölner rechtswissenschaftliche Abhandlungen. Vol. 58. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-169567-9. OCLC 1154231915.

- Julien, Charles André (1970). History of North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, from the Arab Conquest to 1830. Routledge & K. Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-6614-5. OCLC 128197.

- Kaddache, Mahfoud (2003). L'Algérie des Algériens de la préhistoire à 1954 [Algeria of the Algerians: Prehistory to 1954] (in French). Paris-Méditerranée. ISBN 978-2-84272-166-4. OCLC 52106453.

- Konstam, Angus (2016). The Barbary Pirates. 15th–17th Centuries. Elite series. Vol. 213. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1543-9. OCLC 956525803.

- Koskenniemi, Martti; Walter, Rech; Fonseca, Manuel Jiménez (2017). International Law and Empire: Historical Explorations. History and theory of international law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879557-5. OCLC 973375249.

- Krieken, G. S. van (2002). Corsaires et marchands: les relations entre Alger et les Pays-Bas, 1604-1830 [Corsairs and merchants: relations between Algiers and the Netherlands, 1604-1830] (in French). Bouchene. pp. 50–55. ISBN 978-2-912946-35-5. OCLC 1049955030.

- Lange, Erik de (2024). Menacing Tides: Security, Piracy and Empire in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-36414-0. OCLC 1404820369.

- Léon, Galibert (1843). Histoire de l'Algérie, ancienne et moderne, depuis les premiers établissements de Carthaginois jusques et y compris les dernières campagnes du Général Bugeaud. Avec une introduction sur les divers systèmes de colonisation qui ont précédé la conquète française. Furne et Cie. OCLC 848106839.

- Liang, Yuen-Gen (2011). Family and Empire: The Fernández de Córdoba and the Spanish Realm. Haney Foundation series. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0437-7. OCLC 794925808.

- Lowenheim, Oded (2009). Predators and Parasites: Persistent Agents of Transnational Harm and Great Power Authority. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-02225-0. OCLC 743199423.

- Maameri, Fatima (December 2008). Ottoman Algeria in Western Diplomatic History with Particular Emphasis on Relations with the United States of America, 1776-1816 (PDF) (Phd thesis). University of Constantine. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- Martin, B. G. (2003). Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. African studies series. Vol. 18. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53451-2. OCLC 962899280.

- Masters, Bruce (2013). The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516–1918: A Social and Cultural History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06779-0.

- Matar, Nabil (2000). Turks, Moors, and Englishmen in the Age of Discovery. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50571-0. OCLC 1027517028.

- McDougall, James (2017). "Ecologies, Societies, Cultures and the State, 1516–1830". A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–49. doi:10.1017/9781139029230.003. ISBN 978-0-521-85164-0. OCLC 966850065.