Cluster headache: Difference between revisions

ce |

→Differential: Adding/improving reference(s) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

===Differential=== |

===Differential=== |

||

Other types of headache are sometimes mistaken for, or may mimic closely, cluster headaches. Incorrect terms like "cluster migraine" confuse headache types for both practitioner and patient, confound patient's attempts in seeking differential diagnosis and are often the cause of unnecessary diagnostic delay,<ref>{{primary source-inline|date=January 2014}} {{cite journal |author=Klapper JA, Klapper A, Voss T |title=The misdiagnosis of cluster headache: a nonclinic, population-based, Internet survey |journal=Headache |volume=40 |issue=9 |pages=730–5 |year=2000 |month=October |pmid=11091291 }}</ref> ultimately delaying appropriate specialist treatment. |

Cluster headache may be misdiagnosed as migraine or [[sinusitis]].<ref name=Tfelt-Hansen2012>{{cite journal|last=Tfelt-Hansen|first=PC|coauthors=Jensen, RH|title=Management of cluster headache.|journal=CNS drugs|date=2012 Jul 1|volume=26|issue=7|pages=571-80|pmid=22650381}}</ref> Often there is a delay of several years before the correct diagnosis is reached.<ref name=Tfelt-Hansen2012 /> Other types of headache are sometimes mistaken for, or may mimic closely, cluster headaches. Incorrect terms like "cluster migraine" confuse headache types for both practitioner and patient, confound patient's attempts in seeking differential diagnosis and are often the cause of unnecessary diagnostic delay,<ref>{{primary source-inline|date=January 2014}} {{cite journal |author=Klapper JA, Klapper A, Voss T |title=The misdiagnosis of cluster headache: a nonclinic, population-based, Internet survey |journal=Headache |volume=40 |issue=9 |pages=730–5 |year=2000 |month=October |pmid=11091291 }}</ref> ultimately delaying appropriate specialist treatment. |

||

*[[Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania]] (CPH) is another unilateral headache condition, without the male predominance usually seen in cluster headache. Paroxysmal hemicrania may also be episodic. CPH typically responds "absolutely" to treatment with the [[anti-inflammatory]] drug [[indomethacin]]<ref name=IHS/> where in most cases cluster headache typically will show no positive Indomethacin response, making "Indomethacin response" an important diagnostic tool for specialist practitioners seeking correct differential diagnosis between the two separate headache conditions.{{mcn|date=January 2014}} Attack profile associated with paroxysmal hemicrania may be generally of shorter duration, often lasting from 2–30 minutes, but may occur more or less frequently than cluster headache attacks.{{mcn|date=January 2014}} |

*[[Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania]] (CPH) is another unilateral headache condition, without the male predominance usually seen in cluster headache. Paroxysmal hemicrania may also be episodic. CPH typically responds "absolutely" to treatment with the [[anti-inflammatory]] drug [[indomethacin]]<ref name=IHS/> where in most cases cluster headache typically will show no positive Indomethacin response, making "Indomethacin response" an important diagnostic tool for specialist practitioners seeking correct differential diagnosis between the two separate headache conditions.{{mcn|date=January 2014}} Attack profile associated with paroxysmal hemicrania may be generally of shorter duration, often lasting from 2–30 minutes, but may occur more or less frequently than cluster headache attacks.{{mcn|date=January 2014}} |

||

Revision as of 01:00, 3 January 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Cluster headache | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 0.1% |

Cluster headache is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, severe headaches on one side, typically around the eye.[1] There are often accompanying features during a cluster headache such as eye watering, nasal congestion and swelling of and around the eye, all confined to the side with the pain.[1] Patients typically experience repeated attacks of excruciatingly severe unilateral headache pain.[2]

Cluster headache attacks often occur periodically; spontaneous remissions may interrupt active periods of pain, though about 10-15% of chronic cluster headache sufferers never remit.[2] The condition affects approximately 0.1% of the population and men are more commonly affected than women, by a ratio of 2.1:1.[3] There is currently no known cause, or cure for a cluster headache. Cluster headache belongs to a group of primary headache disorders, classified as "Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias" or (TACs).

Signs and symptoms

Cluster headaches are recurring bouts of excruciating unilateral headache attacks[3] of extreme intensity.[4] The duration of a typical cluster headache attack ranges from about 15 to 180 minutes. The onset of an attack is rapid and most often without preliminary signs that are characteristic in migraine. Some sufferers report preliminary sensations of pain in the general area of attack, often referred to by patients as "shadows", that may warn them an attack is lurking or imminent, or these symptoms may linger after an attack has passed, or even between attacks.[5] Though a cluster headache is strictly unilateral, there are some documented cases of "side-shift" between cluster periods, extremely rare, simultaneously (within the same cluster period) bilateral headache.[6]

Pain

The pain of cluster headaches is remarkably greater than in other headache conditions, including severe migraine. The term "headache" does not adequately convey the severity of the condition; experts have suggested that the disease may be the most painful condition known to medical science. Female patients have reported cluster headache pain as being more severe than pain of natural childbirth.[7] Peter Goadsby, a neurologist and headache specialist at the Kings College Hospital, has commented:

"Cluster headache is probably the worst pain that humans experience. I know that's quite a strong remark to make, but if you ask a cluster headache patient if they've had a worse experience, they'll universally say they haven't. ... Women with cluster headache will tell you that an attack is worse than giving birth. So you can imagine that these people give birth without anaesthetic once or twice a day, for six, eight or ten weeks at a time, and then have a break."[8]

The pain is lancinating or boring/drilling in quality and is located behind the eye (periorbital) or in the temple, sometimes radiating to the jaw. Analogies frequently used to describe the pain are a red-hot poker inserted into the eye, or a spike penetrating from the top of the head, behind one eye, radiating down to the base of the brain. Some patients compare the location and quality of pain intensity with ice-cream headache,[9] with similar speed of onset of attack, but instead with regular recurrence and longer duration of up to 3 hours per attack.

Other symptoms

The typical symptoms of cluster headache are grouping (cluster) of recurring headache attacks of severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain. If left untreated, attack frequency will range from one to 8 attacks every 24 hours.[2] The headache attack is accompanied by at least one of the following autonomic symptoms: ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (pupil constriction) conjunctival injection (redness of the conjunctiva), lacrimation (tearing), rhinorrhea (runny nose), and, less commonly, facial blushing, swelling, or sweating, commonly but not always appearing on the same side of the head as the pain.[2]

During a cluster attack a patient may experience restlessness, the sufferer often pacing the room or rocking back and forth. The sufferer may also report photosensitivity, or display an aversion to light (Photophobia) and/or sensitivity to noise (phonophobia) during the attack. Nausea rarely accompanies a cluster headache, though it has been reported.[3] In some patients the neck may feel stiff or tender in the aftermath of a headache, with jaw or tooth pain sometimes present. Sufferers sometimes report feeling as though their nose is blocked and that they are unable to breathe out of one of their nostrils.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Secondary effects can include, but are not limited to; inability to organize thoughts and plans, physical exhaustion, confusion, agitation, aggressiveness, depression and anxiety.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Patients tend to dread facing another headache and may adjust their physical or social activities or sometimes seek assistance to accomplish seemingly normal tasks. Patients may hesitate to schedule plans in reaction to the clock-like regularity, or conversely, the unpredictability of the pain schedule. These factors can lead patients to experience generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorder,[10] serious depressive disorders,[11] social withdrawal and isolation.[12]

Recurrence

Cluster headaches are occasionally referred to as "alarm clock headaches" because of their ability to wake patients from sleep and because of the regularity of their timing: both the individual attacks and the cluster grouping themselves can have a metronomic regularity; attacks striking at a precise time of day each morning or night is typical. In some patients the grouping of headache clusters can occur more often around solstices, or spring and autumn equinoxes, sometimes showing circannual periodicity. This has prompted researchers to speculate involvement, or dysfunction of the brain's Hypothalamus, which controls the body's "biological clock" and circadian rhythm.[13][14] Conversely, some patients' attack frequency may be highly unpredictable, showing no predictable periodicity at all.

In episodic cluster headaches, these attacks occur once or more daily, often at the same times each day, for a period of several weeks, followed by a headache-free period lasting weeks, months, or years. Approximately 10–15% of cluster headache sufferers are chronic; they can experience multiple headaches every day for years, sometimes without any remission.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

In accordance with the International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria, cluster headaches occurring in two or more cluster periods, lasting from 7 to 365 days with a pain-free remission of one month or longer between the clusters may be classified as episodic. If attacks occur for more than a year without pain-free remission of at least one month, the condition is classified chronic.[2]

Chronic cluster headaches occur continuously without any "remission" periods between cycles. Chronic sufferers may have "high" and "low" variation in cycles, meaning the frequency and severity of attacks may change without predictability, for a period of time. The amount of change during these cycles varies between individuals and does not demonstrate complete remission seen in sufferers of the episodic form of cluster headache. The condition may change unpredictably, from chronic to episodic and from episodic to chronic.[15] Remission periods lasting for decades before the resumption of clusters have been known to occur.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Causes

There may be a genetic component to cluster headaches, although no single gene has yet been identified as the cause. One study shows first-degree relatives of sufferers are only slightly more likely to have the condition than the population at large.[16]

Smoking

Tobacco consumption may trigger, or worsen the course of cluster headaches,[17] and the affliction is often found in people with a heavy addiction to cigarette smoking. However it is not clear if there is a causal relationship between smoking and cluster headaches. Some researchers think that people who suffer from cluster headaches may be predisposed to certain traits, including smoking or other lifestyle habits.[18] Some patients report that even exposure to passive smoke can be enough to trigger or worsen attacks.[19]

Hypothalamus

Among the most widely accepted

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

theories is one developed by Peter Goadsby and holds that cluster headaches are due to a dysfunction of the hypothalamus; the theory may explain why cluster headaches frequently strike around the same time each day, and during a particular season.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

One of the functions the hypothalamus performs is regulation of the biological clock. Metabolic abnormalities have also been reported in patients.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

|

|

|

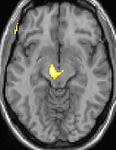

| Positron emission tomography (PET) shows brain areas being activated during pain | ||

|

|

|

| Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) shows brain area structural differences | ||

The above positron emission tomography (PET) pictures indicate the brain areas which are activated during pain of attack only, compared to pain free periods. These pictures show brain areas which are active during pain in yellow/orange colour (called "pain matrix"). The area in the centre (in all three views) is specifically activated during cluster headache only. The bottom row voxel-based morphometry (VBM) pictures show structural brain differences between cluster headache patients and people without headaches; only a portion of the hypothalamus is different.[20]

Pathophysiology

Cluster headache has been historically classified as vascular headaches; for decades, it has been proposed that intense pain was caused by dilation of blood vessels which was thought to create pressure on the trigeminal nerve. While this theory was thought to be the immediate cause of the pain, the etiology (underlying cause or causes) is not fully understood and cluster headache pathogenesis remains the subject of ongoing research and debate.[21] Investigations into the vascular theory of headache disorders are helping to identify the role of other possible causative mechanisms in cluster headaches.[22]

Diagnosis

Cluster headache is a primary headache condition in its own right, with no known cause. Cluster headaches are often left misdiagnosed, mismanaged, or undiagnosed for many years, often being confused with migraine, "cluster-like" headache (or mimics), cluster headache subtypes, other Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs) or sometimes other types of primary or secondary headache syndrome.[23] Cluster-like head pain may be diagnosed as secondary headache and therefore, not cluster headache.[2]

A headache diary can be useful in tracking when and where the pain occurs, how severe it is, how long the pain lasts. A record of coping strategies used will also help both patient and physician distinguish between headache type. Collected data from the patient on frequency, severity and duration of headache attacks is a necessary tool for initial and correct differential diagnosis in headache conditions.[24] A detailed oral patient history is required for correct differential diagnosis, as there are no current confirmatory tests for cluster headache.

Correct diagnosis of cluster headache is a challenge for practitioners, and is especially problematic for patients attending hospital emergency departments, where staff are not trained in the diagnosis of rare or complex chronic disease, like cluster headache.[25] Although experienced ER staff can be sometimes be trained to detect headache types,[26] cluster headaches are not life-threatening.[27]

Individuals with cluster headache typically experience a lengthy delay before correct diagnosis.[28][23] Patients are often misdiagnosed due to reported neck, tooth, jaw, and sinus symptoms and may unnecessarily endure many years of referral to ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists for investigation of sinuses, dentists for tooth assessment, chiropractors and manipulative therapists for treatment, Psychiatrists, Psychologists and many other medical disciplines, before their headache symptoms may be correctly diagnosed.[29] Figures on time to correct diagnosis vary, averaging many years to reach correct differential diagnosis.[30]

Fayyaz Ahmed, Consultant Neurologist, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust says, of differentiating and managing common headache disorder subtypes" "Undergraduates receive very little training on headache disorders even in their placement within the neurosciences. It is, therefore, unlikely that a medical graduate would be expected to make an accurate diagnosis on headache disorders".[31]

Differential

Cluster headache may be misdiagnosed as migraine or sinusitis.[32] Often there is a delay of several years before the correct diagnosis is reached.[32] Other types of headache are sometimes mistaken for, or may mimic closely, cluster headaches. Incorrect terms like "cluster migraine" confuse headache types for both practitioner and patient, confound patient's attempts in seeking differential diagnosis and are often the cause of unnecessary diagnostic delay,[33] ultimately delaying appropriate specialist treatment.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH) is another unilateral headache condition, without the male predominance usually seen in cluster headache. Paroxysmal hemicrania may also be episodic. CPH typically responds "absolutely" to treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin[2] where in most cases cluster headache typically will show no positive Indomethacin response, making "Indomethacin response" an important diagnostic tool for specialist practitioners seeking correct differential diagnosis between the two separate headache conditions.

Attack profile associated with paroxysmal hemicrania may be generally of shorter duration, often lasting from 2–30 minutes, but may occur more or less frequently than cluster headache attacks.This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014)This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014)

- SUNCT - "Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache with Conjunctival injection and Tearing" is another headache syndrome belonging to the group of Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgis (TACs)[2] that may also be confused with or misdiagnosed as cluster headache.[34]

- Trigeminal Neuralgia is a unilateral headache syndrome that may be confused with, or misdiagnosed as cluster headache[29] or "cluster-like" headache, also seen as an overlap condition in SUNCT patients. Overlap in diagnostic features of these different headache conditions can often lead to misdiagnosis.[35]

Prevention

Preventive treatments are used to attempt to provide the sufferer with a long-term reduction or the possibility of elimination of cluster headache attacks. These techniques are generally used in combination with abortive and transitional techniques in order to obtain the best therapeutic results.[3] A wide variety of prophylactic medicines are in use, and patient response to these is highly variable.

The calcium channel blocker Verapamil is a first-line recommended preventative therapy.[3] Dosages of 360–480 mg daily have been found effective in reducing cluster headache attack frequency.[3] Despite its success in randomized controlled trial, only four percent of patients with cluster headache report verapamil use.[3] European guidelines suggest the use of the drug at a dose of at least 240 mg daily.[36]

Steroids, such as prednisolone and dexamethasone may also be effective, and are typically effective within 24–48 hours.[unreliable medical source?][37] This transitional therapy is generally discontinued after 8–10 days of treatment, as preventative treatments become more effective within the body, and as long-term use can result in very severe side effects.[unreliable medical source?][37] Typical dosages are between 50–80 mg daily and then tapered down over the course of 10–12 days.[3]

Methysergide, lithium and the anticonvulsant topiramate are recommended as alternative treatments.[36]

Cluster headache specifically, may be triggered by nitrates, nitric oxide producing substances[non-primary source needed][38] and some alcohol.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Glyceryl trinitrate tablets used in the treatment of heart disease may be used in a clinical environment to trigger cluster attack.[non-primary source needed][39][non-primary source needed][40]

Management

Cluster headache treatments are available that may assist a person who has cluster headaches. While effective treatments for cluster headache exist, they are commonly underused due to misdiagnosis of the syndrome.[3] Often, it is confused with migraine or other causes of headache.[23]

Treatment for cluster headache is divided into three primary categories: abortive, transitional, and preventative.[37] Some abortive treatments may only decrease the duration or intensity of the headache pain, rather than eliminating it entirely. Transitional treatments are short-term preventative treatments that are intended to relieve the pain whilst seeking a suitable preventative medication. Practitioners will use transitional medication whilst escalating dosages of preventives until these preventive treatments are proven effective, well tolerated, appropriate and become active.[37] Preventive treatment is typically indicated for use in managing chronic cluster headache. Presently, the best hope for the majority of intractable cluster headache sufferers remains specialist physician pain management. [citation needed]

Triptans

First-line cluster headache attack abortive treatment is to initiate subcutaneous, intranasal, or oral administration of sumatriptan.[36] Sumatriptan and zolmitriptan have both been shown to dramatically improve symptoms during an attack or indeed abort an attack completely.[41]

Triptans were developed to treat migraines, but have proven over many years to be quite safe and very effective when used as an abortive drug when aborting active cluster headache attack. Because of the vasoconstrictive action of triptans, this drug group may be contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, or circulatory disorders such as Raynaud's disease or syndrome. A high frequency of acute cluster attacks may preclude a maximum dosage of Triptans.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Oxygen

Rapid inhalation of 100% oxygen (oxygen therapy) is used to treat many patients.[3][36] Oxygen is typically administered via non-rebreather mask at 7-10 liters per minute for 15–20 minutes.[3] Patients who prove unresponsive to 7-10 LPM of Oxygen may have their recommended flow rate increased to 15 LPM.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Neurostimulation

Several medical devices are used to prevent cluster headache.[42] Neurostimulation devices used in cluster headache treatment typically propose a neuromodulatory mechanism of action.[43] Both invasive and non-invasive techniques have been used with varying degrees of reported success. Invasive procedures may include surgical implantation of devices for: Occipital Nerve Stimulation (ONS),

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

sphenopalatine ganglion (SPG) stimulation,

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

Vagal Nerve Stimulation (VNS),

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

and hypothalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS).[44] Non-invasive procedures may employ neuromodulatory techniques using non-implantable external devices; Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) and Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS).[unreliable medical source?][43]

Opioids

Opioid medications may present significant risk of actually making the pain of headache syndromes worse.[45][46]

The use of opioid medication in management of chronic cluster headache may not be appropriate, given the lack of efficacy in CH and the known well established long term dependency, addiction and withdrawal syndromes associated with ongoing, long-term opioid use.[47] Prescription of opioid medication in cluster headache can lead to diagnostic delay, undertreatment, and mismanagement of the condition.[48]

Other

Other therapies that have been trialled include:

- Lithium, melatonin, and anti-convulsant drugs such as valproic acid, topiramate and gabapentin are medications that can be tried as second-line treatment options.[49]

- Various surgical interventions have been tried in treatment-resistant cases but due to the invasiveness, limited evidence of effectiveness and uncertainty regarding adverse effects, in most cases, surgery is not currently a recommended treatment.[49]

- Vasoconstrictors such as ergot compounds are sometimes used immediately at onset of attack. Cafergot, a vasoconstrictor combination of caffeine and ergot, has been demonstrated in some cases to abort cluster headaches within 40 minutes of ingestion. BOL (2-bromo lysergic acid diethylamide), a non-psychedelic form of the ergot-derived psychedelic LSD, has shown promise in the treatment of cluster headaches.[unreliable medical source?][50]

- Some isolated case reports suggest that ingesting LSD, psilocybin or cannabis can reduce cluster headache pain and interrupt cluster headache cycles.[51]

- Treatments such as botox injection have shown mixed levels of success.[non-primary source needed][52]

Epidemiology

Migraines are more common than cluster headache, which effects about 0.2% of the general population,[53] or 56 to 326 people per 100,000.[54]

While migraines are diagnosed more often in women than men, cluster headaches are more prevalent in men. The male-to-female ratio in cluster headache diagnoses ranges from 4:1 to 10:1. Although cluster headache can occur at any age, the disease primarily emerges between the ages of 20 to 50 years.[unreliable medical source?][55] This gap between the sexes has narrowed over the past few decades and it is not clear whether cluster headaches are becoming more frequent in women, or whether they are being more frequently reported, or perhaps diagnosed more effectively.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

History

The first complete description of cluster headache was given by the London neurologist Wilfred Harris in 1926. He named the disease Migrainous neuralgia.[56][57][58] Cluster headache symptoms have been described in medical texts as far back as 1745, and probably earlier.[59]

The condition was originally named Horton's Cephalalgia after B.T Horton, who postulated the first theory as to their pathogenesis. His original paper describes the severity of the headaches as being able to take normal men and force them to attempt or complete suicide. From Horton's 1939 paper on cluster headache:

"Our patients were disabled by the disorder and suffered from bouts of pain from two to twenty times a week. They had found no relief from the usual methods of treatment. Their pain was so severe that several of them had to be constantly watched for fear of suicide. Most of them were willing to submit to any operation which might bring relief."[60]

Cluster headaches have been called by several other names in the past including Erythroprosopalgia of Bing, Ciliary neuralgia, Erythromelalgia of the head, Horton's headache (named after Bayard T. Horton, an American neurologist), Histaminic cephalalgia, Petrosal neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, Vidian neuralgia, Sluder's neuralgia, and Hemicrania angioparalyticia.[61]

Society and culture

Robert Shapiro, a Professor of Neurology and Headache specialist at the University Health Center, University of Georgia says that cluster headache is about as common as multiple sclerosis with a similar disability level; he says that over the past decade, the NIH has spent $1.872 billion on research into multiple sclerosis, while less than $2 million has gone to cluster headache research over the last 25 years.[62]

See also

References

- ^ a b Nesbitt, AD (2012 Apr 11). "Cluster headache". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 344: e2407. PMID 22496300.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "IHS Classification ICHD-II 3.1.2 Chronic cluster headache". The International Headache Society. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Beck E, Sieber WJ, Trejo R (2005). "Management of cluster headache". Am Fam Physician (Review). 71 (4): 717–24. PMID 15742909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Capobianco DJ, Dodick DW (2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of cluster headache". Semin Neurol (Review). 26 (2): 242–59. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939925. PMID 16628535.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Marmura MJ, Pello SJ, Young WB (2010). "Interictal pain in cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 30 (12): 1531–4. doi:10.1177/0333102410372423. PMID 20974600.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Meyer EL, Laurell K, Artto V; et al. (2009). "Lateralization in cluster headache: a Nordic multicenter study". J Headache Pain. 10 (4): 259–63. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0129-z. PMC 3451747. PMID 19495933.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matharu M, Goadsby P (2001). "Cluster Headache". Practical Neurology. 1: 42. doi:10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00505.x.

- ^ Presenter: Natasha Mitchell. Producer: Brigitte Seega (9 August 1999). "Cluster Headaches". Health Report. Radio National.

- ^ http://www.nbcnews.com/health/brain-freeze-agony-ecstasy-ice-cream-1C6437739[full citation needed]

- ^ Robbins MS (2013). "The psychiatric comorbidities of cluster headache". Curr Pain Headache Rep (Review). 17 (2): 313. doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0313-8. PMID 23296640.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Liang JF, Chen YT, Fuh JL; et al. (2013). "Cluster headache is associated with an increased risk of depression: a nationwide population-based cohort study". Cephalalgia. 33 (3): 182–9. doi:10.1177/0333102412469738. PMID 23212294.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Jensen RM, Lyngberg A, Jensen RH (2007). "Burden of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 27 (6): 535–41. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01330.x. PMID 17459083.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pringsheim T (2002). "Cluster headache: evidence for a disorder of circadian rhythm and hypothalamic function". Can J Neurol Sci (Review). 29 (1): 33–40. PMID 11858532.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dodick DW, Eross EJ, Parish JM, Silber M (2003). "Clinical, anatomical, and physiologic relationship between sleep and headache". Headache. 43 (3): 282–92. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03055.x. PMID 12603650.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Torelli P, Manzoni GC (2002). "What predicts evolution from episodic to chronic cluster headache?". Curr Pain Headache Rep (Review). 6 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1007/s11916-002-0026-5. PMID 11749880.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pinessi L, Rainero I, Rivoiro C, Rubino E, Gallone S (2005). "Genetics of cluster headache: an update". J Headache Pain (Review). 6 (4): 234–6. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0194-x. PMC 3452030. PMID 16362673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Tiraferri I, Righi F, Zappaterra M; et al. (2013). "Can cigarette smoking worsen the clinical course of cluster headache?". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 1 (Suppl 1): P54. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-1-S1-P54.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Schürks M, Diener HC (2008). "Cluster headache and lifestyle habits". Curr Pain Headache Rep (Review). 12 (2): 115–21. PMID 18474191.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Rozen TD (2010). "Cluster headache as the result of secondhand cigarette smoke exposure during childhood". Headache. 50 (1): 130–2. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01542.x. PMID 19804394.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ DaSilva AF, Goadsby PJ, Borsook D (2007). "Cluster headache: a review of neuroimaging findings". Curr Pain Headache Rep (Review). 11 (2): 131–6. PMID 17367592.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goadsby PJ (2009). "The vascular theory of migraine--a great story wrecked by the facts". Brain (Review). 132 (Pt 1): 6–7. doi:10.1093/brain/awn321. PMID 19098031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leone M, Cecchini AP, Tullo V, Curone M, Di Fiore P, Bussone G (2013). "Cluster headache: what has changed since 1999?". Neurol. Sci. (Review). 34 Suppl 1: S71–3. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1365-1. PMID 23695050.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c [non-primary source needed] van Vliet JA, Eekers PJ, Haan J, Ferrari MD (2003). "Features involved in the diagnostic delay of cluster headache". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 74 (8): 1123–5. PMC 1738593. PMID 12876249.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|layurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Headache diary: helping you manage your headace" (PDF). NPS.org.au. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ Friedman BW, Grosberg BM (2009). "Diagnosis and management of the primary headache disorders in the emergency department setting". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. (Review). 27 (1): 71–87, viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2008.09.005. PMC 2676687. PMID 19218020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Clarke CE, Edwards J, Nicholl DJ, Sivaguru A, Davies P, Wiskin C (2005). "Ability of a nurse specialist to diagnose simple headache disorders compared with consultant neurologists". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 76 (8): 1170–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.057968. PMC 1739753. PMID 16024902.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000786.htm[full citation needed]

- ^ [non-primary source needed] Bahra A, Goadsby PJ (2004). "Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache". Acta Neurol. Scand. 109 (3): 175–9. PMID 14763953.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b [non-primary source needed] Van Alboom E, Louis P, Van Zandijcke M, Crevits L, Vakaet A, Paemeleire K (2009). "Diagnostic and therapeutic trajectory of cluster headache patients in Flanders". Acta Neurol Belg. 109 (1): 10–7. PMID 19402567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Geweke LO (2002). "Misdiagnosis of cluster headache". Curr Pain Headache Rep (Review). 6 (1): 76–82. PMID 11749882.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ahmed F (2012). "Headache disorders: differentiating and managing the common subtypes". British Journal of Pain. 6 (3): 124–32. doi:10.1177/2049463712459691.

- ^ a b Tfelt-Hansen, PC (2012 Jul 1). "Management of cluster headache". CNS drugs. 26 (7): 571–80. PMID 22650381.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Klapper JA, Klapper A, Voss T (2000). "The misdiagnosis of cluster headache: a nonclinic, population-based, Internet survey". Headache. 40 (9): 730–5. PMID 11091291.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alore PL, Jay WM, Macken MP (2006). "SUNCT syndrome: Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache with Conjunctival injection and Tearing". Semin Ophthalmol. 21 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1080/08820530500509317. PMID 16517438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Benoliel R (August 2012). "Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias". British Journal of Pain. 6 (3): 106–23. doi:10.1177/2049463712456355.

- ^ a b c d May A, Leone M, Afra J; et al. (2006). "EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias" (PDF). Eur J Neurol. 13 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x. PMID 16987158.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d [unreliable medical source?] Michigan Headache & Neurological Institute. "Cluster Headache Update". Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ [non-primary source needed]Ashina M, Bendtsen L, Jensen R, Olesen J (2000). "Nitric oxide-induced headache in patients with chronic tension-type headache". Brain. 123 ( Pt 9): 1830–7. PMID 10960046.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Dahl A, Russell D, Nyberg-Hansen R, Rootwelt K (1990). "Cluster headache: transcranial Doppler ultrasound and rCBF studies". Cephalalgia. 10 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1990.1002087.x. PMID 2113834.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [non-primary source needed] Daugaard D, Tfelt-Hansen P, Thomsen LL, Iversen HK, Olesen J (2010). "No effect of pure oxygen inhalation on headache induced by glyceryl trinitrate". J Headache Pain. 11 (2): 93–5. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0190-7. PMC 3452287. PMID 20143247.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Law S, Derry S, Moore RA (2010). "Triptans for acute cluster headache". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Review) (4): CD008042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008042.pub2. PMID 20393964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bartsch T, Paemeleire K, Goadsby PJ (2009). "Neurostimulation approaches to primary headache disorders". Curr. Opin. Neurol. (Review). 22 (3): 262–8. PMID 19434793.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b [unreliable medical source?] "Global year against headache: October 2011–October 2012". Intenational Association for the Study of Pain. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ Leone M, Proietti Cecchini A, Franzini A; et al. (2008). "Lessons from 8 years' experience of hypothalamic stimulation in cluster headache". Cephalalgia (Review). 28 (7): 787–97, discussion 798. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01627.x. PMID 18547215.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson JL, Hutchinson MR, Williams DB, Rolan P (2013). "Medication-overuse headache and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: A review of mechanisms, a neuroimmune hypothesis and a novel approach to treatment". Cephalalgia (Review). 33 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1177/0333102412467512. PMID 23144180.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Rice KC, Maier SF (2009). "The "toll" of opioid-induced glial activation: improving the clinical efficacy of opioids by targeting glia". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. (Review). 30 (11): 581–91. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.002. PMC 2783351. PMID 19762094.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saper JR, Da Silva AN (2013). "Medication overuse headache: history, features, prevention and management strategies". CNS Drugs. 27 (11): 867–77. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0081-y. PMID 23925669.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Paemeleire K, Evers S, Goadsby PJ (2008). "Medication-overuse headache in patients with cluster headache". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 12 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0023-4. PMID 18474192.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Chen PK, Chen HM, Chen WH; et al. (2011). "[Treatment guidelines for acute and preventive treatment of cluster headache]" (PDF). Acta Neurol Taiwan (Review) (in Chinese). 20 (3): 213–27. PMID 22009127.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [unreliable medical source?] The Treatment of Cluster Headaches Using 2-Bromo-Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. The Beckley Foundation

- ^ Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A (2011). "Alternative headache treatments: nutraceuticals, behavioral and physical treatments". Headache (Review). 51 (3): 469–83. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x. PMID 21352222.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [non-primary source needed]Sostak P, Krause P, Förderreuther S, Reinisch V, Straube A (2007). "Botulinum toxin type-A therapy in cluster headache: an open study". J Headache Pain. 8 (4): 236–41. doi:10.1007/s10194-007-0400-0. PMID 17901920.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett MH, French C, Schnabel A, Wasiak J, Kranke P (2008). "Normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen therapy for migraine and cluster headache". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (REview) (3): CD005219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005219.pub2. PMID 18646121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Torelli P, Castellini P, Cucurachi L, Devetak M, Lambru G, Manzoni G (2006). "Cluster headache prevalence: methodological considerations. A review of the literature" (PDF). Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense (Review). 77 (1): 4–9. PMID 16856701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [unreliable medical source?]"Diamond Headache Clinc". Diamondheadache.com. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Harris W.: Neuritis and Neuralgia. Oxford: Oxford Univ.Press; 1926[page needed]

- ^ Bickerstaff, Edwinr. (1959). "The Periodic Migrainous Neuralgia of Wilfred Harris". The Lancet. 273 (7082): 1069. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90651-8.

- ^ Boes, CJ; Capobianco, DJ; Matharu, MS; Goadsby, PJ (2002). "Wilfred Harris' early description of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 22 (4): 320–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00360.x. PMID 12100097.

- ^ Pearce, JMS. "Gerardi van Swieten: descriptions of episodic cluster headache" http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2117620/

- ^ Horton BT, MacLean AR, Craig WMK (1939). "A new syndrome of vascular headache: results of treatment with histamine: preliminary report". Mayo Clinic Proc. 14: 257.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephen D. Silberstein, Richard B. Lipton. Peter J. Goadsgy. "Headache in Clinical Practice." Second edition. Taylor & Francis. 2002.[page needed]

- ^ http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/05/16/researcher-unlocking-mysteries-migraines/2165363/[full citation needed]