Ciclosporin: Difference between revisions

m →Adverse effects: added citation. |

formatted ref and simplified |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

Treatment may be associated with a number of potentially serious [[adverse drug reaction]]s (ADRs). |

Treatment may be associated with a number of potentially serious [[adverse drug reaction]]s (ADRs). |

||

ADRs can include [[gingival enlargement|enlargement of the gums]], [[seizure|convulsion]]s, [[peptic ulcer]]s, [[pancreatitis]], [[fever]], [[vomiting]], [[diarrhea]], [[confusion]], [[hypercholesterolemia]], [[dyspnea]], [[numbness]] and [[tingling]] particularly of the lips, [[pruritus]], high [[blood pressure]], [[potassium]] retention possibly leading to [[hyperkalemia]], [[kidney]] and [[liver]] dysfunction ([[nephrotoxicity]]<ref name="pmid19218475 ">{{cite journal |author=Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M|title=Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity |journal=Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. |volume=4 |issue= 2 |pages=481–509 |year=2009 |pmid=19218475 |doi=10.2215/CJN.04800908}}</ref> and [[hepatotoxicity]]), burning sensations at finger tips, and an increased vulnerability to opportunistic fungal and viral [[infection]]s. In short, it is nephrotoxic, neurotoxic, increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma and infections, and often causes hypertension (due to renal vasoconstriction and increased sodium reabsorption). The latter may result in serious adverse cardiovascular events; |

ADRs can include [[gingival enlargement|enlargement of the gums]], [[seizure|convulsion]]s, [[peptic ulcer]]s, [[pancreatitis]], [[fever]], [[vomiting]], [[diarrhea]], [[confusion]], [[hypercholesterolemia]], [[dyspnea]], [[numbness]] and [[tingling]] particularly of the lips, [[pruritus]], high [[blood pressure]], [[potassium]] retention possibly leading to [[hyperkalemia]], [[kidney]] and [[liver]] dysfunction ([[nephrotoxicity]]<ref name="pmid19218475 ">{{cite journal |author=Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M|title=Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity |journal=Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. |volume=4 |issue= 2 |pages=481–509 |year=2009 |pmid=19218475 |doi=10.2215/CJN.04800908}}</ref> and [[hepatotoxicity]]), burning sensations at finger tips, and an increased vulnerability to opportunistic fungal and viral [[infection]]s. In short, it is nephrotoxic, neurotoxic, increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma and infections, and often causes hypertension (due to renal vasoconstriction and increased sodium reabsorption). The latter may result in serious adverse cardiovascular events; thus it is recommended that prescribers find the lowest effective dose for people requiring long term treatment treatment.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Robert|first1=N|last2=Wong|first2=GW|last3=Wright|first3=JM|title=Effect of cyclosporine on blood pressure.|journal=The Cochrane database of systematic reviews|date=20 January 2010|issue=1|pages=CD007893|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD007893.pub2|pmid=20091657}}</ref> Ciclosporin also causes enlargement of the gums and increased hair growth which is not seen with [[tacrolimus]] (another calcineurin inhibitor). |

||

An alternate form of the drug, '''cyclosporin G''' (OG37-324), has been found to be much less [[nephrotoxic]] than the standard ciclosporin (cyclosporin A).<ref name="pmid7492487">{{cite journal |author=Henry ML, Elkhammas EA, Davies EA, Ferguson RM |title=A clinical trial of cyclosporine G in cadaveric renal transplantation|journal=Pediatr. Nephrol. |volume=9 |issue=Suppl |pages=S49–51 |year=1995 |pmid=7492487 |doi=10.1007/BF00867684}}</ref> Cyclosporin G ([[molecular mass]] 1217) differs from cyclosporin A in the [[amino acid]] 2 position, where an L-[[norvaline]] replaces the α-[[Alpha-Aminobutyric acid|aminobutyric acid]].<ref name="pmid2860538">{{cite journal |author=Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Rolles K, Drakopoulos S, Jamieson NV |title=Cyclosporin G: immunosuppressive effect in dogs with renal allografts |journal=Lancet |volume=1 |issue=8441|page=1342 |year=1985 |pmid=2860538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92844-2}}</ref> |

An alternate form of the drug, '''cyclosporin G''' (OG37-324), has been found to be much less [[nephrotoxic]] than the standard ciclosporin (cyclosporin A).<ref name="pmid7492487">{{cite journal |author=Henry ML, Elkhammas EA, Davies EA, Ferguson RM |title=A clinical trial of cyclosporine G in cadaveric renal transplantation|journal=Pediatr. Nephrol. |volume=9 |issue=Suppl |pages=S49–51 |year=1995 |pmid=7492487 |doi=10.1007/BF00867684}}</ref> Cyclosporin G ([[molecular mass]] 1217) differs from cyclosporin A in the [[amino acid]] 2 position, where an L-[[norvaline]] replaces the α-[[Alpha-Aminobutyric acid|aminobutyric acid]].<ref name="pmid2860538">{{cite journal |author=Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Rolles K, Drakopoulos S, Jamieson NV |title=Cyclosporin G: immunosuppressive effect in dogs with renal allografts |journal=Lancet |volume=1 |issue=8441|page=1342 |year=1985 |pmid=2860538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92844-2}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:53, 9 January 2016

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsaɪkləˈspɔːrɪn/[1] |

| Trade names | Neoral, Sandimmune |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601207 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, IV, ophthalmic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable |

| Metabolism | Hepatic CYP3A4 |

| Elimination half-life | Variable (about 24 hours) |

| Excretion | Biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.569 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C62H111N11O12 |

| Molar mass | 1202.61 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

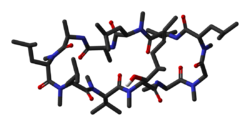

Ciclosporin, also spelled cyclosporine and cyclosporin, and known as ciclosporin A,[3] cyclosporine A, or cyclosporin A (often shortened to CsA) is an immunosuppressant drug widely used in organ transplantation to prevent rejection. It reduces the activity of the immune system by interfering with the activity and growth of T cells.[4][5]

It was initially isolated from the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum (Beauveria nivea), found in a soil sample obtained in 1969 from Hardangervidda, Norway, by Hans Peter Frey, a Sandoz biologist.[6] Most peptides are synthesized by ribosomes, but ciclosporin is a cyclic nonribosomal peptide of 11 amino acids and contains a single D-amino acid, which is rarely encountered in nature.[7]

It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[8]

Medical uses

Ciclosporin is approved by the FDA to prevent and treat graft-versus-host disease in bone-marrow transplantation and to prevent rejection of kidney, heart, and liver transplants.[9][10] It is also approved in the US for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis,[10] as an ophthalmic emulsion for the treatment of dry eyes[11] and as a treatment for persistent nummular keratitis following adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis.[12]

In addition to these indications, ciclosporin is also used in severe atopic dermatitis, Kimura disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, chronic autoimmune urticaria, acute systemic mastocytosis, and, infrequently, in rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases, although it is only used in severe cases.[citation needed]

Ciclosporin has also been used to help treat patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis and autoimmune urticaria that do not respond to treatment with steroids.[13] This drug is also used as a treatment of posterior or intermediate uveitis with noninfective etiology.[citation needed]

It is sometimes prescribed in veterinary cases, particularly in extreme cases of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia.[14]

Adverse effects

Treatment may be associated with a number of potentially serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

ADRs can include enlargement of the gums, convulsions, peptic ulcers, pancreatitis, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, hypercholesterolemia, dyspnea, numbness and tingling particularly of the lips, pruritus, high blood pressure, potassium retention possibly leading to hyperkalemia, kidney and liver dysfunction (nephrotoxicity[15] and hepatotoxicity), burning sensations at finger tips, and an increased vulnerability to opportunistic fungal and viral infections. In short, it is nephrotoxic, neurotoxic, increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma and infections, and often causes hypertension (due to renal vasoconstriction and increased sodium reabsorption). The latter may result in serious adverse cardiovascular events; thus it is recommended that prescribers find the lowest effective dose for people requiring long term treatment treatment.[16] Ciclosporin also causes enlargement of the gums and increased hair growth which is not seen with tacrolimus (another calcineurin inhibitor).

An alternate form of the drug, cyclosporin G (OG37-324), has been found to be much less nephrotoxic than the standard ciclosporin (cyclosporin A).[17] Cyclosporin G (molecular mass 1217) differs from cyclosporin A in the amino acid 2 position, where an L-norvaline replaces the α-aminobutyric acid.[18]

| Ciclosporin | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | N/A |

| OPM superfamily | 174 |

| OPM protein | 1cwa |

Ciclosporin is listed as IARC Group 1 carcinogens (sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in humans).[19]

Mechanism of action

In medicine, the most important effect of ciclosporin is to lower the activity of T cells and their immune response.

Ciclosporin binds to the cytosolic protein cyclophilin (immunophilin) of lymphocytes, especially T cells. This complex of ciclosporin and cyclophilin inhibits calcineurin, which, under normal circumstances, is responsible for activating the transcription of interleukin 2. In T-cells, activation of the T-cell receptor normally increases intracellular calcium, which acts via calmodulin to activate calcineurin. Calcineurin then dephosphorylates the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFATc), which moves to the nucleus of the T-cell and increases the activity of genes coding for IL-2 and related cytokines. Ciclosporin prevents the dephosphorylation of NF-AT by binding to cyclophilin.[20] It also inhibits lymphokine production and interleukin release and, therefore, leads to a reduced function of effector T-cells. It does not affect cytostatic activity.

Ciclosporin affects mitochondria by preventing the mitochondrial permeability transition pore from opening, thus inhibiting cytochrome c release, a potent apoptotic stimulation factor. This is not the primary mechanism of action for clinical use, but is also an important effect for research on apoptosis.

Ciclosporin binds to the cyclophilin D protein (CypD) that constitutes part of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP),[21][22] and by inhibiting the calcineurin phosphatase pathway.[21][23][24]

The MPTP is found in the mitochondrial membrane of cardiac myocytes (heart muscle cells) and moves calcium ions (Ca2+

) into the mitochondria.[21][22] When open, Ca2+

enters the mitochondria, disrupting transmembrane potential (the electric charge across a membrane). If unregulated, this can contribute to mitochondrial swelling and dysfunction.[22] To allow for normal contraction, intracellular Ca2+

increases, and the MPTP in turn opens, shuttling Ca2+

into the mitochondria.[22]

Calcineurin is a Ca2+

-activated phosphatase (enzyme that removes a phosphate group from substrate) that regulates cardiac hypertrophy.[23][25][26] Regulation occurs through NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells) activation, which, when dephosphorylated, binds to GATA and forms a transcription factor (protein that can bind DNA and alter the expression of DNA) with ability to control the hypertrophic gene (2). Activation of calcineurin causes increases in hypertrophy.[23][25]

Metabolism and metabolite activity

Ciclosporin is highly metabolized in humans and animals after ingestion. The resulting metabolites include cyclosporin B, C, D, E, H, L, and others.[27] Ciclosporin metabolites have been found to have lower immunosuppressant activity than CsA (approximately <10%), and are associated with higher nephrotoxicity.[28] Individual ciclosporin metabolites have been isolated and characterized but do not appear to be extensively studied.

Biosynthesis

Ciclosporin is synthesized by a nonribosomal peptide synthetase, ciclosporin synthetase. The enzyme contains an adenylation domain, a thiolation domain, a condensation domain, and an N-methyltransferase domain. The adenylation domain is responsible for substrate recognition and activation, whereas the thiolation domain covalently binds the adenylated amino acids to phosphopantetheine, and the condensation domain elongates the peptide chain. Ciclosporin synthetase substrates include L-valine, L-leucine, L-alanine, glycine, 2-aminobutyric acid, 4-methylthreonine, and D-alanine, which is the starting amino acid in the biosynthetic process.[29] With the adenylation domain, ciclosporin synthetase generates the acyl-adenylated amino acids, then covalently binds the amino acid to phosphopantetheine through a thioester linkage. Some of the amino acid substrates become N-methylated by S-adenosyl methionine. The cyclization step releases ciclosporin from the enzyme.[30] Amino acids such as D-Ala and butenyl-methyl-L-threonine indicate ciclosporin synthetase requires the action of other enzymes such as a D-alanine racemase. The racemization of L-Ala to D-Ala is pyridoxal phosphate-dependent. The formation of butenyl-methyl-L-threonine is performed by a butenyl-methyl-L-threonine polyketide synthase that uses acetate/malonate as its starting material.[31]

History

The immunosuppressive effect of ciclosporin was discovered in 1972 by employees of Sandoz (now Novartis) in Basel, Switzerland, in a screening test on immune suppression designed and implemented by Hartmann F. Stähelin. The success of ciclosporin in preventing organ rejection was shown in kidney transplants by R.Y. Calne and colleagues at the University of Cambridge,[32] and in liver transplants performed by Thomas Starzl at the University of Pittsburgh Hospital. The first patient, on 9 March 1980, was a 28-year-old woman.[33] Ciclosporin was subsequently approved for use in 1983.

Formulations

The drug exhibits very poor solubility in water, and, as a consequence, suspension and emulsion forms of the drug have been developed for oral administration and for injection. Ciclosporin was originally brought to market by Sandoz, now Novartis, under the brand name Sandimmune, which is available as soft gelatin capsules, as an oral solution, and as a formulation for intravenous administration. These are all nonaqueous compositions.[34] A newer microemulsion,[35] orally-administered formulation, Neoral,[36] is available as a solution and as soft gelatin capsules (10 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg and 100 mg). The Neoral compositions are designed to form microemulsions in contact with water. Generic ciclosporin preparations have been marketed under various trade names, including Cicloral (Sandoz/Hexal), Gengraf (Abbott) and Deximune (Dexcel Pharma). Since 2002, a topical emulsion of ciclosporin for treating inflammation caused by keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye syndrome) has been marketed under the trade name Restasis (0.05%). Inhaled ciclosporin formulations are in clinical development, and include a solution in propylene glycol and liposome dispersions.

The drug is also available in a dog preparation manufactured by Novartis Animal Health called Atopica. Atopica is indicated for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. Unlike the human form of the drug, the lower doses used in dogs mean the drug acts as an immunomodulator and has fewer side effects than in humans. The benefits of using this product include the reduced need for concurrent therapies to bring the condition under control. It is available as an ophthalmic ointment for dogs called Optimmune, manufactured by Intervet, which is part of Merck.

Name

Ciclosporin is the INN and BAN while cyclosporine is the USAN and cyclosporin is a former BAN.

Research

Neuroprotection

Ciclosporin is currently in a phase II/III (adaptive) clinical study in Europe to determine its ability to ameliorate neuronal cellular damage and reperfusion injury (phase III) in traumatic brain injury. This multi-center study is being organized by NeuroVive Pharma and the European Brain Injury Consortium using NeuroVive's formulation of ciclosporin called NeuroSTAT (also known by its cardioprotection trade name of CicloMulsion). This formulation uses a lipid emulsion base instead of cremophor and ethanol.[37] NeuroSTAT was recently compared to Sandimmune in a phase I study and found to be bioequivalent. In this study, NeuroSTAT did not exhibit the anaphylactic and hypersensitivity reactions found in cremophor- and ethanol-based products.[38]

Ciclosporin has been investigated as a possible neuroprotective agent in conditions such as traumatic brain injury, and has been shown in animal experiments to reduce brain damage associated with injury.[39] Ciclosporin blocks the formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, which has been found to cause much of the damage associated with head injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Ciclosporin's neuroprotective properties were first discovered in the early 1990s when two researchers (Eskil Elmér and Hiroyuki Uchino) were conducting experiments in cell transplantation. An unintended finding was that CsA was strongly neuroprotective when it crossed the blood–brain barrier.[40] This same process of mitochondrial destruction through the opening of the MPT pore is implicated in making traumatic brain injuries much worse.[41]

Cardiac disease

Ciclosporin has been used experimentally to treat cardiac hypertrophy[21][25] (an increase in cell volume).

Inappropriate opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) manifests in ischemia[21] (blood flow restriction to tissue) and reperfusion injury[21] (damage occurring after ischemia when blood flow returns to tissue), after myocardial infarction[23] (heart attack) and when mutations in mitochondrial DNA polymerase occur.[21] The heart attempts to compensate for disease state by increasing the intracellular Ca2+

to increase the contractility cycling rates.[22] Constitutively high levels of mitochondrial Ca2+

cause inappropriate MPTP opening leading to a decrease in the cardiac range of function, leading to cardiac hypertrophy as an attempt to compensate for the problem.[22][23]

CsA has been shown to decrease cardiac hypertrophy by affecting cardiac myocytes in many ways. CsA binds to cyclophilin D to block the opening of MPTP, and thus decreases the release of protein cytochrome C, which can cause programmed cell death.[21][22][42] CypD is a protein within the MPTP that acts as a gate; binding by CsA decreases the amount of inappropriate opening of MPTP, which decreases the intramitochondrial Ca2+

.[22] Decreasing intramitochondrial Ca2+

allows for reversal of cardiac hypertrophy caused in the original cardiac response.[22] Decreasing the release of cytochrome C caused decreased cell death during injury and disease.[21] CsA also inhibits the phosphatase calcineurin pathway (14).[21][23][26] Inhibition of this pathway has been shown to decrease myocardial hypertrophy.[23][25][26]

See also

- Cremophor EL (additive in Sandimmune)

- Castor oil (additive in Sandimmune)

- Alcohol (additive in Sandimmune and Neoral)

- Discovery and development of mTOR inhibitors

- Voclosporin, an analog of ciclosporin

References

- ^ "cyclosporin". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. n.d. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1863293/

- ^ Henry J. Kaminski (26 November 2008). Myasthenia Gravis and Related Disorders. Springer. p. 163.

Cyclosporine is derived from a fungus and is a cyclic undecapeptide with actions directed exclusively on T cells.

- ^ Cantrell DA, Smith KA (1984). "The interleukin-2 T-cell system: a new cell growth model". Science. 224 (4655): 1312–1316. doi:10.1126/science.6427923. PMID 6427923.

- ^ Svarstad, H; Bugge, HC; Dhillion, SS (2000). "From Norway to Novartis: Cyclosporin from Tolypocladium inflatum in an open access bioprospecting regime". Biodiversity and Conservation. 9 (11): 1521–1541. doi:10.1023/A:1008990919682.

- ^ Borel JF (2002). "History of the discovery of cyclosporin and of its early pharmacological development". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114 (12): 433–7. PMID 12422576.

Some sources list the fungus under an alternative species name Hypocladium inflatum gams such as Pritchard and Sneader in 2005:

* Pritchard DI (2005). "Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens". Drug Discov. Today. 10 (10): 688–91. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7. PMID 15896681.

* "Ciclosporin". Drug Discovery — A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 298–299 (refs. page 315).

However, the name, "Beauveria nivea", also appears in several other articles including in a 2001 online publication by Harriet Upton entitled "Origin of drugs in current use: the cyclosporin story" (retrieved June 19, 2005). Mark Plotkin states in his book Medicine Quest, Penguin Books 2001, pages 46-47, that in 1996 mycology researcher Kathie Hodge found that it is in fact a species of Cordyceps. - ^ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ^ SandImmune Label

- ^ a b "DailyMed - NEORAL- cyclosporine capsule, liquid filled NEORAL- cyclosporine solution". nih.gov.

- ^ "DailyMed - RESTASIS - cyclosporine emulsion". nih.gov.

- ^ "Lokales Cyclosporin A bei Nummuli nach Keratoconjunctivitis epidemica Eine Pilotstudie - Springer". springer.com.

- ^ Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A; et al. (1994). "Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy". N. Engl. J. Med. 330 (26): 1841–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. PMID 8196726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palmeiro, BS (Jan 2013). "Cyclosporine in veterinary dermatology". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 43 (1): 153–71. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.09.007. PMID 23182330.

- ^ Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M (2009). "Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity". Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4 (2): 481–509. doi:10.2215/CJN.04800908. PMID 19218475.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert, N; Wong, GW; Wright, JM (20 January 2010). "Effect of cyclosporine on blood pressure". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007893. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007893.pub2. PMID 20091657.

- ^ Henry ML, Elkhammas EA, Davies EA, Ferguson RM (1995). "A clinical trial of cyclosporine G in cadaveric renal transplantation". Pediatr. Nephrol. 9 (Suppl): S49–51. doi:10.1007/BF00867684. PMID 7492487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Rolles K, Drakopoulos S, Jamieson NV (1985). "Cyclosporin G: immunosuppressive effect in dogs with renal allografts". Lancet. 1 (8441): 1342. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92844-2. PMID 2860538.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–110

- ^ William F. Ganong. Review of medical physiology, 22nd edition, Lange medical books, chapter 27, page 530. ISBN 0-07-144040-2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mott JL, Zhang D, Freeman JC, Mikolajczak P, Chang SW, Zassenhaus HP (July 2004). "Cardiac disease due to random mitochondrial DNA mutations is prevented by cyclosporin A". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 319 (4): 1210–5. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.104. PMID 15194495.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Elrod JW, Wong R, Mishra S; et al. (October 2010). "Cyclophilin D controls mitochondrial pore-dependent Ca2+

exchange, metabolic flexibility, and propensity for heart failure in mice". J. Clin. Invest. 120 (10): 3680–7. doi:10.1172/JCI43171. PMC 2947235. PMID 20890047.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Youn TJ, Piao H, Kwon JS; et al. (December 2002). "Effects of the calcineurin dependent signaling pathway inhibition by cyclosporin A on early and late cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction". Eur. J. Heart Fail. 4 (6): 713–8. doi:10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00120-4. PMID 12453541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Handschumacher RE, Harding MW, Rice J, Drugge RJ, Speicher DW (November 1984). "Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A". Science. 226 (4674): 544–7. doi:10.1126/science.6238408. PMID 6238408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Mende U, Kagen A, Cohen A, Aramburu J, Schoen FJ, Neer EJ (November 1998). "Transient cardiac expression of constitutively active Galphaq leads to hypertrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy by calcineurin-dependent and independent pathways". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (23): 13893–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13893. PMC 24952. PMID 9811897.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lim HW, De Windt LJ, Mante J; et al. (April 2000). "Reversal of cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic disease models by calcineurin inhibition". J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32 (4): 697–709. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2000.1113. PMID 10756124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang, Paul C. et al. "Isolation of 10 Cyclosporine Metabolites from Human Bile." Drug Metabolism and Disposition 17.3 (1989): 292-96. Nih.gov. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Copeland, Kenneth R. "Immunosuppressive Activity of Cyclosporine Metabolites Compared and Characterized by Mass Spectrometry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance."Clinical Chemistry 36.2 (1990): 225-29. Web. 28 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Dittmann J, Wenger RM, Kleinkauf H, Lawen A (January 1994). "Mechanism of cyclosporin A biosynthesis. Evidence for synthesis via a single linear undecapeptide precursor". J. Biol. Chem. 269 (4): 2841–6. PMID 8300618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoppert M, Gentzsch C, Schörgendorfer K (October 2001). "Structure and localization of cyclosporin synthetase, the key enzyme of cyclosporin biosynthesis in Tolypocladium inflatum" (PDF). Arch. Microbiol. 176 (4): 285–93. doi:10.1007/s002030100324. PMID 11685373.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dewick, P. (2001) Medicinal Natural Products. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2nd ed.

- ^ Calne RY, White DJG, Thiru S, et al. Cyclosporin A in patients receiving renal allografts from cadaver donors. The Lancet 1978/II:1323-1327

- ^ Starzl TE, Klintmalm GB, Porter KA, Iwatsuki S, Schröter GP (1981). "Liver transplantation with use of cyclosporin a and prednisone". N. Engl. J. Med. 305 (5): 266–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM198107303050507. PMC 2772056. PMID 7017414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sandimmune Prescribing Information

- ^ Gibaud, S. P.; Attivi, D. (2012). "Microemulsions for oral administration and their therapeutic applications". Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery: 1. doi:10.1517/17425247.2012.694865.

- ^ Neoral Prescribing Information

- ^ Administrator. "Hem - NeuroVive Pharmaceutical AB". neurovive.com.

- ^ Ehinger, K. H. J., Hansson, J. J., Sjovall, F., Elmer, E. "Bioequivalence and Tolerability Assessment of a Novel Intravenous Ciclosporin Lipid Emulsion Compared to Branded Ciclosporin in Cremophor EL." Clinical Drug Investigation 2012 Nov. 22 Epub ahead of print.

- ^ Sullivan PG, Thompson M, Scheff SW (2000). "Continuous infusion of cyclosporin A postinjury significantly ameliorates cortical damage following traumatic brain injury". Exp. Neurol. 161 (2): 631–7. doi:10.1006/exnr.1999.7282. PMID 10686082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Uchino H, Elmér E, Uchino K, Lindvall O, Siesjö BK (1995). "Cyclosporin A dramatically ameliorates CA1 hippocampal damage following transient forebrain ischaemia in the rat". Acta Physiol. Scand. 155 (4): 469–71. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09999.x. PMID 8719269.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sullivan PG, Sebastian AH, Hall ED (2011). "Therapeutic window analysis of the neuroprotective effects of cyclosporine A after traumatic brain injury". J. Neurotrauma. 28 (2): 311–8. doi:10.1089/neu.2010.1646. PMC 3037811. PMID 21142667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilkinson ST, Johnson DB, Tardif HL, Tome ME, Briehl MM (2010). "Increased cytochrome c correlates with poor survival in aggressive lymphoma". Oncol Lett. 1 (2): 227–230. doi:10.3892/ol_00000040. PMC 2927837. PMID 20798784.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)