COVID-19 testing: Difference between revisions

→Polymerase chain reaction: Add reference to qPCR as an abbreviation |

→Polymerase chain reaction: It's important to clarify that all these terms refer to the same thing, or people get confused when they see the different terms in the literature. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

===Current infection=== |

===Current infection=== |

||

====Polymerase chain reaction==== |

====Polymerase chain reaction==== |

||

[[Polymerase chain reaction]] (PCR) is a process that causes a very small well-defined segment of [[DNA]] to be [[DNA replication|amplified]], or multiplied many hundreds of thousands of times, so that there is enough of it to be detected and analyzed. Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 do not contain [[DNA]] but only [[RNA]].<ref name=iaea_rt-pcr/> When a respiratory sample is collected from the person being tested it is treated with certain chemicals<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.assaygenie.com/rna-extraction-for-covid-19-testing |title= RNA Extraction |publisher=AssayGenie |access-date=7 May 2020 }}</ref><ref name=iaea_rt-pcr/> which remove extraneous substances and extract only the RNA from the sample. [[Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction]] (RT-PCR) is a technique that first uses [[Reverse transcriptase |reverse transcription]] to convert the extracted RNA into DNA and then uses PCR to amplify a piece of the resulting DNA, creating enough to be examined in order to determine if it matches the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2.<ref name=iaea_rt-pcr>{{cite web |url=https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/how-is-the-covid-19-virus-detected-using-real-time-rt-pcr |title= How is the COVID-19 Virus Detected using Real Time RT-PCR? |publisher= IAEA|access-date=5 May 2020|date = 27 March 2020}}</ref> [[Real-time polymerase chain reaction| Real-time PCR]] (qPCR)<ref>{{cite web |last1=Bustin |first1=Stephen A. |last2=Benes |first2=Vladimir |last3=Garson |first3=Jeremy A. |last4=Hellemans |first4=Jan |last5=Huggett |first5=Jim |last6=Kubista |first6=Mikael |last7=Mueller |first7=Reinhold |last8=Nolan |first8=Tania |last9=Pfaffl |first9=Michael W. |last10=Shipley |first10=Gregory L. |last11=Vandesompele |first11=Jo |last12=Wittwer |first12=Carl T. |title=The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments |url=https://academic.oup.com/clinchem/article/55/4/611/5631762 |website=Clinical Chemistry |pages=611–622 |language=en |doi=10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 |date=1 April 2009}}</ref> provides advantages during the PCR portion of this process, including automating it and enabling high-throughput and more reliable instrumentation, and has become the preferred method.<ref>{{cite web |url= https://gene-quantification.de/bustin-mueller-qpcr-2005.pdf |title= Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and its potential use in clinical diagnosis |publisher=Clinical Science |access-date=5 May 2020|date = 23 September 2005 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/references/ambion-tech-support/rtpcr-analysis/general-articles/rt--pcr-the-basics.html |title= The Basics: RT-PCR |publisher=ThermoFisher Scientific |access-date=5 May 2020}}</ref> Altogether, the combined technique is sometimes abbreviated [[Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction|qRT-PCR]]<ref name="pmid20204872">{{cite book |vauthors=Varkonyi-Gasic E, Hellens RP |title=Plant Epigenetics |chapter=qRT-PCR of Small RNAs |volume=631 |pages=109–22 |year=2010 |pmid=20204872 |doi=10.1007/978-1-60761-646-7_10 |series=Methods in Molecular Biology |isbn=978-1-60761-645-0 }}</ref> or rRT-PCR<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.fda.gov/media/136151/download|title=ACCELERATED EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) SUMMARY COVID-19 RT-PCR TEST (LABORATORY CORPORATION OF AMERICA) |last=|first= |date= |website=FDA |url-status=live |archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=3 April 2020}}</ref> or RT-qPCR,<ref name="pmid20215014">{{cite journal |vauthors=Taylor S, Wakem M, Dijkman G, Alsarraj M, Nguyen M |title=A practical approach to RT-qPCR-Publishing data that conform to the MIQE guidelines |journal=Methods |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=S1–5 |date=April 2010 |pmid=20215014 |doi=10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.005 }}</ref> although sometimes just RT-PCR or PCR is used as an abbreviation. The test can be done on respiratory samples obtained by various methods, including a [[nasopharyngeal swab]] or [[sputum]] sample,<ref name="20200129cdc">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-detection-instructions.html |title=Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV |date=29 January 2020 |website=[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] |access-date=1 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200130202031/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-detection-instructions.html |archive-date=30 January 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> as well as on [[saliva]].<ref name=sciencenews_saliva/> Results are generally available within a few hours to 2 days.<ref name="globenewswire1977226">{{cite web |url=https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/01/30/1977226/0/en/Curetis-Group-Company-Ares-Genetics-and-BGI-Group-Collaborate-to-Offer-Next-Generation-Sequencing-and-PCR-based-Coronavirus-2019-nCoV-Testing-in-Europe.html |title=Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe |date=30 January 2020 |website=GlobeNewswire News Room |access-date=1 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200131201626/https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/01/30/1977226/0/en/Curetis-Group-Company-Ares-Genetics-and-BGI-Group-Collaborate-to-Offer-Next-Generation-Sequencing-and-PCR-based-Coronavirus-2019-nCoV-Testing-in-Europe.html |archive-date=31 January 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> The RT-PCR test performed with throat swabs is only reliable in the first week of the disease. Later on the virus can disappear in the throat while it continues to multiply in the lungs. For infected people tested in the second week, alternatively sample material can then be taken from the deep airways by suction catheter, or coughed up material (sputum) can be used.<ref name="chrdrosten20200326">{{cite web |last=Drosten|first=Christian|url=https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/info/coronaskript146.pdf |title=Coronavirus-Update Folge 22 |date=26 March 2020 |website=NDR |access-date=2 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200331101408/https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/info/coronaskript146.pdf |archive-date=31 March 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> Saliva has been shown to be a common and transient medium for virus transmission<ref name=nature_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41368-020-0080-z |title= Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV |publisher=Nature |access-date=6 May 2020|date = 17 April 2020}}</ref> and results provided to the FDA suggest that testing saliva may be as effective as nasal and throat swabs.<ref name=sciencenews_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-covid-19-where-things-stand-tests-testing-united-states |title= Here's where things stand on COVID-19 tests in the U.S. |publisher= ScienceNews|access-date=6 May 2020|date =17 April 2020 }}</ref> The [[FDA]] has granted [[Emergency Use Authorization]] for a test that collects [[saliva]] instead of using the traditional [[Nasopharyngeal swab|nasal swab]].<ref name=cnn_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/14/health/coronavirus-test-saliva-fda-emergency-use-bn/index.html |title= FDA authorizes Covid-19 saliva test for emergency use |publisher=CNN |access-date=1 May 2020|date =14 April 2020 }}</ref> It is believed that this will reduce the risk for health care professionals,<ref name= Rutgers_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.rutgers.edu/news/new-rutgers-saliva-test-coronavirus-gets-fda-approval |title= New Rutgers Saliva Test for Coronavirus Gets FDA Approval |publisher=Rutgers.edu |access-date=1 May 2020|date =13 April 2020 }}</ref> will be much more comfortable for the patient,<ref name=cnn_saliva/> and will enable quarantined people to collect their own samples more efficiently.<ref name=Rutgers_saliva/> According to some experts it is too early to know the operating characteristics of the saliva test, and whether it will prove to be as sensitive as the [[nasopharyngeal swab]] test.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/covid-19-saliva-tests-what-is-the-benefit/ |title= COVID-19 saliva tests: What is the benefit? |publisher= Mayo Clinic|access-date=6 May 2020|date =16 April 2020 }}</ref><ref name=nature_saliva/> Some studies suggest that the diagnostic value of saliva depends on how saliva specimens are collected (from deep throat, from oral cavity, or from salivary glands).<ref name=nature_saliva/> A recent test conducted by the [[Yale University School of Public Health]] found that saliva yielded greater detection sensitivity and consistency throughout the course of infection when compared with samples taken with [[nasopharyngeal swab]]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/resourcespages/select-covid-19-news |title= Yale University School of Public Health finds saliva samples promising alternative to nasopharyngeal swab |publisher= Merck Manual|access-date=6 April 2020|date = 29 April 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite document |url=https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20067835v1 |title= Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection in COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs |publisher= Medrxiv|access-date=5 May 2020|date =22 April 2020 |doi= 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067835 |last1= Wyllie |first1= Anne Louise |last2= Fournier |first2= John |last3= Casanovas-Massana |first3= Arnau |last4= Campbell |first4= Melissa |last5= Tokuyama |first5= Maria |last6= Vijayakumar |first6= Pavithra |last7= Geng |first7= Bertie |last8= Muenker |first8= M. Catherine |last9= Moore |first9= Adam J. |last10= Vogels |first10= Chantal B. F. |last11= Petrone |first11= Mary E. |last12= Ott |first12= Isabel M. |last13= Lu |first13= Peiwen |last14= Lu-Culligan |first14= Alice |last15= Klein |first15= Jonathan |last16= Venkataraman |first16= Arvind |last17= Earnest |first17= Rebecca |last18= Simonov |first18= Michael |last19= Datta |first19= Rupak |last20= Handoko |first20= Ryan |last21= Naushad |first21= Nida |last22= Sewanan |first22= Lorenzo R. |last23= Valdez |first23= Jordan |last24= White |first24= Elizabeth B. |last25= Lapidus |first25= Sarah |last26= Kalinich |first26= Chaney C. |last27= Jiang |first27= Xiaodong |last28= Kim |first28= Daniel J. |last29= Kudo |first29= Eriko |last30= Linehan |first30= Melissa |displayauthors= 29 }}</ref> |

[[Polymerase chain reaction]] (PCR) is a process that causes a very small well-defined segment of [[DNA]] to be [[DNA replication|amplified]], or multiplied many hundreds of thousands of times, so that there is enough of it to be detected and analyzed. Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 do not contain [[DNA]] but only [[RNA]].<ref name=iaea_rt-pcr/> When a respiratory sample is collected from the person being tested it is treated with certain chemicals<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.assaygenie.com/rna-extraction-for-covid-19-testing |title= RNA Extraction |publisher=AssayGenie |access-date=7 May 2020 }}</ref><ref name=iaea_rt-pcr/> which remove extraneous substances and extract only the RNA from the sample. [[Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction]] (RT-PCR) is a technique that first uses [[Reverse transcriptase |reverse transcription]] to convert the extracted RNA into DNA and then uses PCR to amplify a piece of the resulting DNA, creating enough to be examined in order to determine if it matches the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2.<ref name=iaea_rt-pcr>{{cite web |url=https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/how-is-the-covid-19-virus-detected-using-real-time-rt-pcr |title= How is the COVID-19 Virus Detected using Real Time RT-PCR? |publisher= IAEA|access-date=5 May 2020|date = 27 March 2020}}</ref> [[Real-time polymerase chain reaction| Real-time PCR]] (qPCR)<ref>{{cite web |last1=Bustin |first1=Stephen A. |last2=Benes |first2=Vladimir |last3=Garson |first3=Jeremy A. |last4=Hellemans |first4=Jan |last5=Huggett |first5=Jim |last6=Kubista |first6=Mikael |last7=Mueller |first7=Reinhold |last8=Nolan |first8=Tania |last9=Pfaffl |first9=Michael W. |last10=Shipley |first10=Gregory L. |last11=Vandesompele |first11=Jo |last12=Wittwer |first12=Carl T. |title=The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments |url=https://academic.oup.com/clinchem/article/55/4/611/5631762 |website=Clinical Chemistry |pages=611–622 |language=en |doi=10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 |date=1 April 2009}}</ref> provides advantages during the PCR portion of this process, including automating it and enabling high-throughput and more reliable instrumentation, and has become the preferred method.<ref>{{cite web |url= https://gene-quantification.de/bustin-mueller-qpcr-2005.pdf |title= Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and its potential use in clinical diagnosis |publisher=Clinical Science |access-date=5 May 2020|date = 23 September 2005 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/references/ambion-tech-support/rtpcr-analysis/general-articles/rt--pcr-the-basics.html |title= The Basics: RT-PCR |publisher=ThermoFisher Scientific |access-date=5 May 2020}}</ref> Altogether, the combined technique has been described as real-time RT-PCR<ref name="pmid20515509">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kang XP, Jiang T, Li YQ, etal |title=A duplex real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting H5N1 avian influenza virus and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus |journal=Virol. J. |volume=7 |issue= |page=113 |year=2010 |pmid=20515509 |pmc=2892456 |doi=10.1186/1743-422X-7-113 }}</ref> or quantitative RT-PCR<ref name="pmid12325527">{{cite book | author = Joyce C | title = Quantitative RT-PCR. A review of current methodologies | series = Methods Mol. Biol. | volume = 193 | pages = 83–92 | year = 2002 | pmid = 12325527 | doi = 10.1385/1-59259-283-X:083 | isbn = 978-1-59259-283-8 }}</ref> and is sometimes abbreviated [[Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction|qRT-PCR]]<ref name="pmid20204872">{{cite book |vauthors=Varkonyi-Gasic E, Hellens RP |title=Plant Epigenetics |chapter=qRT-PCR of Small RNAs |volume=631 |pages=109–22 |year=2010 |pmid=20204872 |doi=10.1007/978-1-60761-646-7_10 |series=Methods in Molecular Biology |isbn=978-1-60761-645-0 }}</ref> or rRT-PCR<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.fda.gov/media/136151/download|title=ACCELERATED EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) SUMMARY COVID-19 RT-PCR TEST (LABORATORY CORPORATION OF AMERICA) |last=|first= |date= |website=FDA |url-status=live |archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=3 April 2020}}</ref> or RT-qPCR,<ref name="pmid20215014">{{cite journal |vauthors=Taylor S, Wakem M, Dijkman G, Alsarraj M, Nguyen M |title=A practical approach to RT-qPCR-Publishing data that conform to the MIQE guidelines |journal=Methods |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=S1–5 |date=April 2010 |pmid=20215014 |doi=10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.005 }}</ref> although sometimes just RT-PCR or PCR is used as an abbreviation. The test can be done on respiratory samples obtained by various methods, including a [[nasopharyngeal swab]] or [[sputum]] sample,<ref name="20200129cdc">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-detection-instructions.html |title=Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV |date=29 January 2020 |website=[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] |access-date=1 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200130202031/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-detection-instructions.html |archive-date=30 January 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> as well as on [[saliva]].<ref name=sciencenews_saliva/> Results are generally available within a few hours to 2 days.<ref name="globenewswire1977226">{{cite web |url=https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/01/30/1977226/0/en/Curetis-Group-Company-Ares-Genetics-and-BGI-Group-Collaborate-to-Offer-Next-Generation-Sequencing-and-PCR-based-Coronavirus-2019-nCoV-Testing-in-Europe.html |title=Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe |date=30 January 2020 |website=GlobeNewswire News Room |access-date=1 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200131201626/https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/01/30/1977226/0/en/Curetis-Group-Company-Ares-Genetics-and-BGI-Group-Collaborate-to-Offer-Next-Generation-Sequencing-and-PCR-based-Coronavirus-2019-nCoV-Testing-in-Europe.html |archive-date=31 January 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> The RT-PCR test performed with throat swabs is only reliable in the first week of the disease. Later on the virus can disappear in the throat while it continues to multiply in the lungs. For infected people tested in the second week, alternatively sample material can then be taken from the deep airways by suction catheter, or coughed up material (sputum) can be used.<ref name="chrdrosten20200326">{{cite web |last=Drosten|first=Christian|url=https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/info/coronaskript146.pdf |title=Coronavirus-Update Folge 22 |date=26 March 2020 |website=NDR |access-date=2 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200331101408/https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/info/coronaskript146.pdf |archive-date=31 March 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> Saliva has been shown to be a common and transient medium for virus transmission<ref name=nature_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41368-020-0080-z |title= Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV |publisher=Nature |access-date=6 May 2020|date = 17 April 2020}}</ref> and results provided to the FDA suggest that testing saliva may be as effective as nasal and throat swabs.<ref name=sciencenews_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.sciencenews.org/article/coronavirus-covid-19-where-things-stand-tests-testing-united-states |title= Here's where things stand on COVID-19 tests in the U.S. |publisher= ScienceNews|access-date=6 May 2020|date =17 April 2020 }}</ref> The [[FDA]] has granted [[Emergency Use Authorization]] for a test that collects [[saliva]] instead of using the traditional [[Nasopharyngeal swab|nasal swab]].<ref name=cnn_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/14/health/coronavirus-test-saliva-fda-emergency-use-bn/index.html |title= FDA authorizes Covid-19 saliva test for emergency use |publisher=CNN |access-date=1 May 2020|date =14 April 2020 }}</ref> It is believed that this will reduce the risk for health care professionals,<ref name= Rutgers_saliva>{{cite web |url=https://www.rutgers.edu/news/new-rutgers-saliva-test-coronavirus-gets-fda-approval |title= New Rutgers Saliva Test for Coronavirus Gets FDA Approval |publisher=Rutgers.edu |access-date=1 May 2020|date =13 April 2020 }}</ref> will be much more comfortable for the patient,<ref name=cnn_saliva/> and will enable quarantined people to collect their own samples more efficiently.<ref name=Rutgers_saliva/> According to some experts it is too early to know the operating characteristics of the saliva test, and whether it will prove to be as sensitive as the [[nasopharyngeal swab]] test.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/covid-19-saliva-tests-what-is-the-benefit/ |title= COVID-19 saliva tests: What is the benefit? |publisher= Mayo Clinic|access-date=6 May 2020|date =16 April 2020 }}</ref><ref name=nature_saliva/> Some studies suggest that the diagnostic value of saliva depends on how saliva specimens are collected (from deep throat, from oral cavity, or from salivary glands).<ref name=nature_saliva/> A recent test conducted by the [[Yale University School of Public Health]] found that saliva yielded greater detection sensitivity and consistency throughout the course of infection when compared with samples taken with [[nasopharyngeal swab]]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/resourcespages/select-covid-19-news |title= Yale University School of Public Health finds saliva samples promising alternative to nasopharyngeal swab |publisher= Merck Manual|access-date=6 April 2020|date = 29 April 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite document |url=https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20067835v1 |title= Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection in COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs |publisher= Medrxiv|access-date=5 May 2020|date =22 April 2020 |doi= 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067835 |last1= Wyllie |first1= Anne Louise |last2= Fournier |first2= John |last3= Casanovas-Massana |first3= Arnau |last4= Campbell |first4= Melissa |last5= Tokuyama |first5= Maria |last6= Vijayakumar |first6= Pavithra |last7= Geng |first7= Bertie |last8= Muenker |first8= M. Catherine |last9= Moore |first9= Adam J. |last10= Vogels |first10= Chantal B. F. |last11= Petrone |first11= Mary E. |last12= Ott |first12= Isabel M. |last13= Lu |first13= Peiwen |last14= Lu-Culligan |first14= Alice |last15= Klein |first15= Jonathan |last16= Venkataraman |first16= Arvind |last17= Earnest |first17= Rebecca |last18= Simonov |first18= Michael |last19= Datta |first19= Rupak |last20= Handoko |first20= Ryan |last21= Naushad |first21= Nida |last22= Sewanan |first22= Lorenzo R. |last23= Valdez |first23= Jordan |last24= White |first24= Elizabeth B. |last25= Lapidus |first25= Sarah |last26= Kalinich |first26= Chaney C. |last27= Jiang |first27= Xiaodong |last28= Kim |first28= Daniel J. |last29= Kudo |first29= Eriko |last30= Linehan |first30= Melissa |displayauthors= 29 }}</ref> |

||

<gallery class="center" widths="200px" heights="200px" > |

<gallery class="center" widths="200px" heights="200px" > |

||

Revision as of 15:47, 8 May 2020

Template:Use Commonwealth English

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

COVID-19 testing can identify the SARS-CoV-2 virus and includes methods that detect the presence of virus itself (RT-PCR, isothermal nucleic acid amplification, antigen) and those that detect antibodies produced in response to infection. Detection of antibodies (serology) can be used both for diagnosis and population surveillance. Antibody tests show how many people have had the disease, including those whose symptoms were minor or who were asymptomatic. An accurate mortality rate of the disease and the level of herd immunity in the population can be determined from the results of this test. However, the duration and effectiveness of this immune response are still unclear,[1] and the rates of false positives and false negatives must be duly factored into the interpretation.

Due to limited testing, as of March 2020 no countries had reliable data on the prevalence of the virus in their population.[2] As of 24 May, the countries that published their testing data have on average performed a number of tests equal to only 2.6% of their population, and no country has tested samples equal to more than 17.3% of its population.[3] There are variations in how much testing has been done across countries.[4] This variability is also likely to be affecting reported case fatality rates, which have probably been overestimated in many countries, due to sampling bias.[5][6][7]

Test methods

There are two broad categories of test. Some look for the presence of the virus, e.g. the RT-PCR test. Others look for the antibodies which arise when a body is attacked by the virus. The purposes for which the test results are useful is different for the two kinds of test. Another option is to look for lung damage via either CT scan or low oxygen take up since testing via RT-PCR requires the virus to be established and there are a number of false negatives especially in the initial stages.

Current infection

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a process that causes a very small well-defined segment of DNA to be amplified, or multiplied many hundreds of thousands of times, so that there is enough of it to be detected and analyzed. Viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 do not contain DNA but only RNA.[9] When a respiratory sample is collected from the person being tested it is treated with certain chemicals[10][9] which remove extraneous substances and extract only the RNA from the sample. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is a technique that first uses reverse transcription to convert the extracted RNA into DNA and then uses PCR to amplify a piece of the resulting DNA, creating enough to be examined in order to determine if it matches the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2.[9] Real-time PCR (qPCR)[11] provides advantages during the PCR portion of this process, including automating it and enabling high-throughput and more reliable instrumentation, and has become the preferred method.[12][13] Altogether, the combined technique has been described as real-time RT-PCR[14] or quantitative RT-PCR[15] and is sometimes abbreviated qRT-PCR[16] or rRT-PCR[17] or RT-qPCR,[18] although sometimes just RT-PCR or PCR is used as an abbreviation. The test can be done on respiratory samples obtained by various methods, including a nasopharyngeal swab or sputum sample,[19] as well as on saliva.[20] Results are generally available within a few hours to 2 days.[21] The RT-PCR test performed with throat swabs is only reliable in the first week of the disease. Later on the virus can disappear in the throat while it continues to multiply in the lungs. For infected people tested in the second week, alternatively sample material can then be taken from the deep airways by suction catheter, or coughed up material (sputum) can be used.[22] Saliva has been shown to be a common and transient medium for virus transmission[23] and results provided to the FDA suggest that testing saliva may be as effective as nasal and throat swabs.[20] The FDA has granted Emergency Use Authorization for a test that collects saliva instead of using the traditional nasal swab.[24] It is believed that this will reduce the risk for health care professionals,[25] will be much more comfortable for the patient,[24] and will enable quarantined people to collect their own samples more efficiently.[25] According to some experts it is too early to know the operating characteristics of the saliva test, and whether it will prove to be as sensitive as the nasopharyngeal swab test.[26][23] Some studies suggest that the diagnostic value of saliva depends on how saliva specimens are collected (from deep throat, from oral cavity, or from salivary glands).[23] A recent test conducted by the Yale University School of Public Health found that saliva yielded greater detection sensitivity and consistency throughout the course of infection when compared with samples taken with nasopharyngeal swabs.[27][28]

-

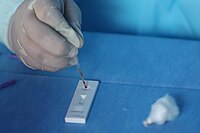

Demonstration of a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 testing

-

Demonstration of a throat swab for COVID-19 testing

-

A PCR machine

Isothermal amplification assays

There are a number of isothermal nucleic acid amplification methods that in principle work like PCR, amplifying a piece of the virus's genome, but are faster than PCR because they don't involve repeated cycles of heating and cooling the sample.

Antigen

An antigen is the part of a pathogen that elicits an immune response. While RT-PCR tests look for RNA from the virus and antibody tests detect human antibodies that have been generated against the virus (detectable days or weeks after the infection sets in), antigen tests look for proteins from the surface of the virus. In the case of a coronavirus these are usually proteins from the surface spikes, and a nasal swab is used to collect samples from the nasal cavity.[29] One of the difficulties has been finding a protein target unique to SARS-CoV-2.[30] There are related coronaviruses that cause the common cold.[31]

Antigen tests are seen by many as the only way it will be possible to scale up testing to the numbers that will really be needed to detect acute infection on the scale required.[29] Isothermal nucleic acid amplification tests, such as the test from Abbot Labs, can only process one sample at a time per machine. RT-PCR tests are accurate but it takes too much time, energy and trained personnel to run the tests.[29] “There will never be the ability on a [PCR] test to do 300 million tests a day or to test everybody before they go to work or to school,” Deborah Birx, head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, said on April 17. “But there might be with the antigen test.”[32]

An antigen test works by taking a nasal swab from a patient and exposing that to paper strips that contain artificial antibodies designed to bind to coronavirus antigens. Any antigens that are present will bind to the strips and give a visual readout. The process takes less than 30 minutes, can deliver results on the spot, and doesn't require expensive equipment or extensive training.[29]

The problem is that in the case of respiratory viruses often there is not enough of the antigen material present in the nasal swab to be detectable.[30] This would especially be true with people who are asymptomatic and who have very little if any nasal discharge. Unlike the RT-PCR test, which amplifies very small amounts of genetic material so that there is enough to detect, there is no amplification of viral proteins in an antigen test.[29][33] According to the World Health Organization (WHO) the sensitivity of similar antigen tests for respiratory diseases like the flu ranges between 34% and 80%. "Based on this information, half or more of COVID-19 infected patients might be missed by such tests, depending on the group of patients tested," the WHO said. Many scientists doubt whether an antigen test can be made reliable enough in time to be useful against Covid-19.[33]

Medical imaging

Chest CT scans are not recommended for routine screening. Radiologic findings in COVID19 are not specific.[34][35] Typical features on CT initially include bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacities with a peripheral or posterior distribution.[35] Subpleural dominance, crazy paving, and consolidation may develop as the disease evolves.[35][36]

-

Typical CT imaging findings

-

CT imaging of rapid progression stage

Past infection

Serology tests rely on drawn blood, not a nasal or throat swab, and can identify people who were infected and have already recovered from Covid-19, including those who didn't know that they had been infected.[37] Most serology tests are in the research stage of development.[38]

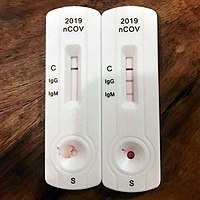

Part of the immune response to infection is the production of antibodies including IgM and IgG. According to the FDA, IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 are generally detectable in blood several days after initial infection, although levels over the course of infection are not well characterized.[39] IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 generally become detectable 10–14 days after infection although they may be detected earlier, and normally peak around 28 days after the onset of infection.[40][41] Since antibodies are slow to present they are not the best markers of acute infection, but as they may persist in the bloodstream for many years they are ideal for detecting historic infections.[29]

Antibody tests can be used to determine the percentage of the population that has contracted the disease and that is therefore presumed to be immune. However, it is still not clear how broad and how long and how effective this immune response is.[1][42] As of April 2020[update] "[s]ome countries are considering issuing so-called immunity passports or risk-free certificates to people who have antibodies against Covid-19, enabling them to travel or return to work assuming that they are protected against reinfection".[43] However, according to the World Health Organization as of 24 April 2020, “There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection.”[44] One of the reasons for the uncertainty is that most, if not all, of the current Covid-19 antibody testing done at large scale is for detection of binding antibodies only and does not measure neutralizing antibodies.[45][46][47] A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic.[48] A binding antibody will bind to the pathogen but the pathogen remains infective; the purpose can be to flag the pathogen for destruction by the immune system.[49] It may even enhance infectivity by interacting with receptors on macrophages.[50] Since most Covid-19 antibody tests will return a positive result if they find only binding antibodies these tests cannot indicate that the person being tested has generated any NAbs which would give him or her protection against re-infection.[46][47]

It is normally expected that if binding antibodies are detected the person also has generated NAbs[47] and for many viral diseases total antibody responses correlate somewhat with NAb responses[51] but this is not yet known for Covid-19. A study of 175 people in China who had recovered from COVID‑19 and had mild symptoms reported that 10 individuals had produced no detectable NAbs at the time of discharge, nor did they develop NAbs thereafter. How these patients recovered without the help of NAbs and whether they were at risk of re-infection of SARS-CoV-2 was left for further exploration.[46][52] An additional source of uncertainty is that even if NAbs are present, several viruses, such as HIV, have evolved mechanisms to evade NAb responses. While this needs to be examined in the context of COVID-19 infection, past experiences with viral infection, in general, argue that in most recovered patients NAb level is a good indicator of protective immunity.[45]

It is presumed that once a person has been infected his or her chance of getting a second infection two to three months later is low, but how long that protective immunity might last is not known.[46] One study determined that reinfection at 29 days post-infection could not occur in SARS-CoV-2 infected rhesus macaques.[53] Studies have indicated that NAbs to the original SARS virus (the predecessor to the current SARS-CoV-2) can remain active in most people for two years[54] and are gone after six years.[55] Nevertheless, memory cells including Memory B cells and Memory T cells can last much longer and may have the ability to greatly lessen the severity of a reinfection.[55]

-

Blood from pipette is then placed onto a COVID-19 rapid diagnostic test device.

Infectivity

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated the following information and recommendation in a "Decision Memo" on 3 May.[56] At this time, data are limited regarding how long after infection people continue to shed infectious SARV-CoV-2 RNA, and can therefore still infect others. Key findings are summarized here.

- Viral burden measured in upper respiratory specimens declines after onset of illness.[57]

- At this time, replication-competent virus has not been successfully cultured more than 9 days after onset of illness. The statistically estimated likelihood of recovering replication-competent virus approaches zero by 10 days.[58]

- As the likelihood of isolating replication-competent virus decreases, anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG can be detected in an increasing number of persons recovering from infection.[59]

- Attempts to culture virus from upper respiratory specimens have been largely unsuccessful when viral burden is in low but detectable ranges (i.e., Ct values higher than 33-35)[56]

- Following recovery from clinical illness, many patients no longer have detectable viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens. Among those who continue to have detectable RNA, concentrations of detectable RNA 3 days following recovery are generally in the range at which replication-competent virus has not been reliably isolated by CDC.[60]

- No clear correlation has been described between length of illness and duration of post-recovery shedding of detectable viral RNA in upper respiratory specimens. [61]

- Infectious virus has not been cultured from urine or reliably cultured from feces;[62] these potential sources pose minimal if any risk of transmitting infection and any risk can be sufficiently mitigated by good hand hygiene.

For an emerging pathogen like SARS-CoV-2, the patterns and duration of illness and infectivity have not been fully described. However, available data indicate that shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in upper respiratory specimens declines after onset of symptoms. At 10 days after illness onset, recovery of replication-competent virus in viral culture (as a proxy of the presence of infectious virus) is decreased and approaches zero. Although persons may produce PCR-positive specimens for up to 6 weeks,[63] it remains unknown whether these PCR-positive samples represent the presence of infectious virus. After clinical recovery, many patients do not continue to shed SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA. Among recovered patients with detectable RNA in upper respiratory specimens, concentrations of RNA after 3 days are generally in ranges where virus has not been reliably cultured by CDC. These data have been generated from adults across a variety of age groups and with varying severity of illness. Data from children and infants are not presently available.[56]

Approaches to testing

After issues with testing accuracy and capacity during January and February, the United States was testing 100,000 people per day by 27 March.[65] In comparison, several European countries have been conducting more daily tests per capita than the United States.[66][67] Three European countries are aiming to conduct 100,000 tests per day – Germany by mid-April, the United Kingdom by the end of April and France by the end of June. Germany has a large medical diagnostics industry, with over 100 testing labs that provided the technology and infrastructure to enable rapid increases in testing. The UK sought to diversify its life sciences companies into diagnostics to scale up testing capacity.[68]

In Germany, the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians said on 2 March, that it had a capacity for about 12,000 tests per day in the ambulatory setting and 10,700 had been tested in the prior week. Costs are borne by the health insurance when the test is ordered by a physician.[69] According to the president of the Robert Koch Institute, Germany has an overall capacity for 160,000 tests per week.[70] As of 19 March drive-in tests were offered in several large cities.[71] As of 26 March, the total number of tests performed in Germany was unknown, because only positive results are reported. Health minister Jens Spahn estimated 200,000 tests per week.[72] A first lab survey revealed that as of the end of March a total of at least 483,295 samples were tested and 33,491 samples (6.9%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.[73]

By the start of April, the United Kingdom was delivering around 10,000 swab tests per day. It set a target for 100,000 per day by the end of April, eventually rising to 250,000 tests per day.[68] The British NHS has announced that it is piloting a scheme to test suspected cases at home, which removes the risk of a patient infecting others if they come to a hospital or having to disinfect an ambulance if one is used.[74]

In drive-through testing for COVID‑19 for suspected cases, a healthcare professional takes sample using appropriate precautions.[75][76] Drive-through centers have helped South Korea do some of the fastest, most-extensive testing of any country.[77] Hong Kong has set up a scheme where suspected patients can stay home, "[the] emergency department will give a specimen tube to the patient", they spit into it, send it back and get a test result a while after.[78]

In Israel, researchers at Technion and Rambam Hospital developed and tested a method for testing samples from 64 patients simultaneously, by pooling the samples and only testing further if the combined sample is found to be positive.[79][80][81] Pool testing was then adopted in Israel, Germany, South Korea,[82] and Nebraska,[83] and the Indian states Uttar Pradesh,[84] West Bengal,[85] Punjab,[86] Chhattisgarh,[87] and Maharashtra.[88]

In Wuhan a makeshift 2000-sq-meter emergency detection laboratory named "Huo-Yan" (Chinese: 火眼, "Fire Eye") was opened on 5 February 2020 by BGI,[89][90] which can process over 10,000 samples a day.[91][90] With the construction overseen by BGI-founder Wang Jian and taking 5-days,[92] modelling has show cases in Hubei would have been 47% higher and the corresponding cost of tackling the quarantine would have doubled if this testing capacity had not come into operation.[citation needed] The Wuhan Laboratory has been promptly followed by Huo-Yan labs in Shenzhen, Tianjin, Beijing, and Shanghai, in a total of 12 cities across China. By 4 March 2020 the daily throughput totals were 50,000 tests per day.[93]

Open source, multiplexed designs released by Origami Assays have been released that can test as many as 1122 patient samples for COVID19 using only 93 assays.[94] These balanced designs can be run in small laboratories without the need for robotic liquid handlers.

By March, shortages and insufficient amounts of reagent has become a bottleneck for mass testing in the EU and UK[95] and the US.[96][97] This has led some authors to explore sample preparation protocols that involve heating samples at 98 °C (208 °F) for 5 minutes to release RNA genomes for further testing.[98][99]

On 31 March it was announced United Arab Emirates was now testing more of its population for Coronavirus per head than any other country, and was on track to scale up the level of testing to reach the bulk of the population.[100] This was through a combination of drive-through capability, and purchasing a population-scale mass-throughput laboratory from Group 42 and BGI (based on their "Huo-Yan" emergency detection laboratories in China). Constructed in 14 days, the lab is capable of conducting tens of thousands RT-PCR tests per day and is the first in the world of this scale to be operational outside of China.[101]

On 8 April 2020, In India, the Supreme Court of India ruled that private labs should be reimbursed at the appropriate time for COVID-19 tests [102] However private labs have stated that they are unable to scale up the testing because of the price cap put on the testing and labs being forced to make advance payment to suppliers while they receive deferred payment from hospitals.[103]

University of California San Francisco conducted PCR tests of 1,845 people in Bolinas, California on April 20–24, almost the entire town. No active infections were detected. Antibody testing was also performed but the results are not yet available.[104]

Production and volume

Blue: CDC lab

Orange: Public health lab

Gray: Data incomplete due to reporting lag

Not shown: Testing at private labs; total exceeded 100,000 per day by 27 March[105]

Different testing recipes targeting different parts of the coronavirus genetic profile were developed in China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The World Health Organization adopted the German recipe for manufacturing kits sent to low-income countries without the resources to develop their own. The German recipe was published on 17 January 2020; the protocol developed by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was not available until 28 January, delaying available tests in the U.S.[106]

China[107] and the United States[108] had problems with the reliability of test kits early in the outbreak, and these countries and Australia[109] were unable to supply enough kits to satisfy demand and recommendations for testing by health experts. In contrast, experts say South Korea's broad availability of testing helped reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus. Testing capacity, largely in private sector labs, was built up over several years by the South Korean government.[110] On 16 March, the World Health Organization called for ramping up the testing programmes as the best way to slow the advance of COVID‑19 pandemic.[111][112]

High demand for testing due to wide spread of the virus caused backlogs of hundreds of thousands of tests at private U.S. labs, and supplies of swabs and chemical reagents became strained.[113]

Available tests

PCR based

When scientists from China first released information on the COVID‑19 viral genome on 11 January 2020, the Malaysian Institute for Medical Research (IMR) successfully produced the “primers and probes” specific to SARS-CoV-2 on the very same day. The IMR's laboratory in Kuala Lumpur had initiated early preparedness by setting up reagents to detect coronavirus using the rt-PCR method.[114] The WHO reagent sequence (primers and probes) released several days later was very similar to that produced in the IMR's laboratory, which was used to diagnose Malaysia's first COVID‑19 patient on 24 January 2020.[115]

Public Health England developed a test by 10 January,[116] using real-time RT-PCR (RdRp gene) assay based on oral swabs.[117] The test detected the presence of any type of coronavirus including specifically identifying SARS-CoV-2. It was rolled out to twelve laboratories across the United Kingdom on 10 February.[118] Another early PCR test was developed by Charité in Berlin, working with academic collaborators in Europe and Hong Kong, and published on 23 January. It used rtRT-PCR, and formed the basis of 250,000 kits for distribution by the World Health Organization (WHO).[119] The South Korean company Kogenebiotech developed a clinical grade, PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 detection kit (PowerChek Coronavirus) approved by Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) on 4 February 2020.[120] It looks for the "E" gene shared by all beta coronaviruses, and the RdRp gene specific to SARS-CoV-2.[121]

In China, BGI Group was one of the first companies to receive emergency use approval from China's National Medical Products Administration for a PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 detection kit.[122]

In the United States, the CDC distributed its SARS-CoV-2 Real Time PCR Diagnostic Panel to public health labs through the International Reagent Resource.[123] One of three genetic tests in older versions of the test kits caused inconclusive results due to faulty reagents, and a bottleneck of testing at the CDC in Atlanta; this resulted in an average of fewer than 100 samples a day being successfully processed throughout the whole of February 2020. Tests using two components were not determined to be reliable until 28 February 2020, and it was not until then that state and local laboratories were permitted to begin testing.[124] The test was approved by the FDA under an EUA.[citation needed]

US commercial labs began testing in early March 2020. As of 5 March 2020 LabCorp announced nationwide availability of COVID‑19 testing based on RT-PCR.[125] Quest Diagnostics similarly made nationwide COVID‑19 testing available as of 9 March 2020.[126]

In Russia, the first COVID‑19 test was developed by the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR, production began on January 24.[127] On 11 February 2020 the test was approved by the Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare.[128]

On 12 March 2020, Mayo Clinic was reported to have developed a test to detect COVID‑19 infection.[129]

On 18 March 2020, the FDA issued EUA to Abbott Laboratories[130] for a test on Abbott's m2000 system; the FDA had previously issued similar authorization to Hologic,[131] LabCorp,[130] and Thermo Fisher Scientific.[132] On 21 March 2020, Cepheid similarly received an EUA from the FDA for a test that takes about 45 minutes on its GeneXpert system; the same system that runs the GeneXpert MTB/RIF.[133][134]

On 13 April, Health Canada approved a test from Spartan Bioscience. Institutions may "test patients" with a handheld DNA analyzer "and receive results without having to send samples away to a [central] lab."[135][136]

Isothermal nucleic amplification

On 27 March 2020, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization for a test by Abbott Laboratories, called ID NOW COVID-19, that uses isothermal nucleic acid amplification technology instead of PCR.[137] The assay amplifies a unique region of the virus's RdRp gene; the resulting copies are then detected with "fluorescently-labeled molecular beacons".[138] The test kit uses the company's "toaster-size" ID NOW device which costs $12,000-$15,000.[139] The device can be used in laboratories or in patient care settings, and provides results in 13 minutes or less.[138] There are currently about 18,000 ID NOW devices in the U.S. and Abbott expects to ramp up manufacturing to deliver 50,000 ID NOW COVID-19 test kits per day.[140]

All visitors to U.S. President Donald Trump are required to undergo the test on site at the White House.[141]

In a study conducted by the Cleveland Clinic, the ID NOW COVID-19 test detected the virus only in 85.2% of the samples that contained it. According to the director of the study a test should be at least 95% reliable. Abbott said that the issue could have been caused by storing the samples in a special solution instead of inserting them directly into the testing machine.[142]

Serology tests

As of 24 April, six tests had been approved for diagnosis in the United States, all under FDA Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).[143] The tests are listed and described at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Other tests have been approved in other countries.[144]

In the United States, as of 28 April, Quest Diagnostics made a COVID-19 antibody test available for purchase to the general public through the QuestDirect service. Cost of the test is approximately US$130. The test requires the individual to visit a Quest Diagnostics location for a blood draw. Results are available days later.[145]

A number of countries are beginning large scale surveys of their populations using these tests.[146][147] A study in California conducted antibody testing in one county and estimated that the number of coronaviruses cases was between 2.5 and 4.2% of the population, or 50 to 85 times higher than the number of confirmed cases.[148][149]

In late March 2020, a number of companies received European approvals for their test kits. The testing capacity is several hundred samples within hours. The antibodies are usually detectable 14 days after the onset of the infection.[150]

WHO Emergency Use Listing

| Date listed | Product name | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| 3 April 2020 | Cobas SARS-CoV-2 qualitative assay for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems | Roche Molecular Systems |

| 7 April 2020 | Coronavirus (COVID-19) genesig rtPCR assay | Primerdesign |

| 9 April 2020 | Abbott Realtime SARS-CoV-2[151] | Abbott Molecular |

| 24 April 2020 | PerkinElmer SARS-CoV-2 Real-time RT-PCR Assay[151] | SYM-BIO LiveScience |

As of 7 April 2020, the WHO had accepted two diagnostic tests for procurement under the Emergency Use Listing procedure (EUL) for use during the COVID‑19 pandemic, in order to increase access to quality-assured, accurate tests for the disease.[152] Both in vitro diagnostics, the tests are genesig Real-Time PCR Coronavirus (COVID‑19) manufactured by Primerdesign, and cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 Systems by Roche Molecular Systems. Approval means that these tests can also be supplied by the United Nations and other procurement agencies supporting the COVID‑19 response.[clarification needed]

Testing accuracy

In March 2020 China[107] reported problems with accuracy in their test kits.

In the United States, the test kits developed by the CDC had "flaws;" the government then removed the bureaucratic barriers that had prevented private testing.[108]

Spain purchased test kits from Chinese firm Shenzhen Bioeasy Biotechnology Co Ltd, but found that results were inaccurate. The firm explained that the incorrect results may be a result of a failure to collect samples or use the kits correctly. The Spanish ministry said it will withdraw the kits that returned incorrect results, and would replace them with a different testing kit provided by Shenzhen Bioeasy.[153]

80% of test kits the Czech Republic purchased from China gave wrong results.[154][155]

Slovakia purchased 1.2 million test kits from China which were found to be inaccurate. Prime Minister Matovič suggested these be dumped into the Danube.[156]

Ateş Kara of the Turkish Health Ministry said the test kits Turkey purchased from China had a "high error rate" and did not "put them into use."[157][158]

The UK purchased 3.5 million test kits from China but in early April 2020 announced these were not usable.[159][160][161]

On 21 April 2020, the Indian Council of Medical Research has advised Indian states to stop using the rapid antibody test kits purchased from China after receiving complaints from one state. Rajasthan health minister Raghu Sharma on 21 April said the kits gave only 5.4 percent accurate results against the expectation of 90 percent accuracy.[162]

Confirmatory testing

WHO recommends that countries that do not have testing capacity and national laboratories with limited experience on COVID‑19 send their first five positives and the first ten negative COVID‑19 samples to one of the 16 WHO reference laboratories for confirmatory testing.[163][164] Out of the 16 reference laboratories, 7 are in Asia, 5 in Europe, 2 in Africa, 1 in North America and 1 in Australia.[165]

Clinical effectiveness

Testing, followed with quarantine of those who tested positive and tracing of those with whom the SARS-CoV-2 positive people had had contact, resulted in positive outcomes.[clarification needed].[citation needed]

Italy

Researchers working in the Italian town of Vò, the site of the first COVID‑19 death in Italy, conducted two rounds of testing on the entire population of about 3,400 people, about ten days apart. About half the people testing positive had no symptoms, and all discovered cases were quarantined. With travel to the commune restricted, this eliminated new infections completely.[166]

Singapore

With aggressive contact tracing, inbound travel restrictions, testing, and quarantining, the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore has proceeded much more slowly than in other developed countries [dubious – discuss], but without extreme restrictions like forced closure of restaurants and retail establishments. Many events have been cancelled, and Singapore did start advising residents to stay at home on 28 March, but schools reopened on time after holiday break on 23 March,[167] even though schools did close moving to "full home-based learning" on 8 April.[168]

U.S. aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt

After 94% of the 4,800 crew had been tested roughly 60 percent of the over 600 sailors who tested positive did not have symptoms.[169]

Russia

On 27 April, Russia passed the 3 million test mark and had 183,000 people under medical supervision because they were suspected of having the virus[170] with 87,147 people having tested positive for the virus and total confirmed deaths at 794.[171] On 28 April Anna Popova head of Federal Service for Surveillance in Healthcare (Roszdravnadzor) in a presidential update stated that there were now 506 laboratories testing and that 45% of those tested have no symptoms with the number having pneumonia reducing from 25% to 20% and only 5% of patients with a severe form. 40% of infections were from family members. The speed of people reporting illness has improved from 6 days to the day people find symptoms. Antibody testing was carried out on 3,200 Moscow doctors and 20% have immunity.[172]

Others

Several other countries, such as Iceland[173] and South Korea,[174] have also managed the pandemic with aggressive contact tracing, inbound travel restrictions, testing, and quarantining, but with less aggressive lock-downs. A statistical study has found that countries that have tested more, relative to the number of deaths, have much lower case fatality rates, probably because these countries are better able to detect those with only mild or no symptoms.[5] A subsequent study has also found that countries that have tested more widely also have a younger age distribution of cases, relative to the wider population.[175]

Research and development

A test which uses monoclonal antibodies which bind to the nucleocapsid protein (N protein) of the SARS-CoV-2 is being developed in Taiwan, with the hope that it can provide results in 15 to 20 minutes just like a rapid influenza test.[176] The World Health Organization raised concerns on 8 April that these tests need to be validated for the disease and are in a research stage only.[177] The United States Food and Drug Administration approved an antibody test on 2 April,[178] but some researchers warn that such tests should not drive public health decisions unless the percentage of COVID‑19 survivors who are producing neutralizing antibodies is also known.[42]

Virus testing statistics by country

The figures are influenced by the country's testing policy. If two countries are alike in every respect, including having the same spread of infection, and one of them has a shortage of testing capability, it may only test those showing symptoms while the other country having greater access to testing may test both those showing symptoms and others chosen at random. A country that only tests people showing symptoms will have a higher figure for “% (Percentage of positive tests)” than a country that also tests people chosen at random.[179] If two countries are alike in every respect, including which people they test, the one that tests more people will have a higher "Positive / million people."

| Country or region | Date[a] | Tested | Units[b] | Confirmed (cases) |

Confirmed / tested, % |

Tested / population, % |

Confirmed / population, % |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 Dec 2020 | 154,767 | samples | 49,621 | 32.1 | 0.40 | 0.13 | [180] | |

| 18 Feb 2021 | 428,654 | samples | 96,838 | 22.6 | 15.0 | 3.4 | [181] | |

| 2 Nov 2020 | 230,553 | samples | 58,574 | 25.4 | 0.53 | 0.13 | [182][183] | |

| 23 Feb 2022 | 300,307 | samples | 37,958 | 12.6 | 387 | 49.0 | [184] | |

| 2 Feb 2021 | 399,228 | samples | 20,981 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 0.067 | [185] | |

| 6 Mar 2021 | 15,268 | samples | 832 | 5.4 | 15.9 | 0.86 | [186] | |

| 16 Apr 2022 | 35,716,069 | samples | 9,060,495 | 25.4 | 78.3 | 20.0 | [187] | |

| 29 May 2022 | 3,099,602 | samples | 422,963 | 13.6 | 105 | 14.3 | [188] | |

| 9 Sep 2022 | 78,548,492 | samples | 10,112,229 | 12.9 | 313 | 40.3 | [189] | |

| 1 Feb 2023 | 205,817,752 | samples | 5,789,991 | 2.8 | 2,312 | 65.0 | [190] | |

| 11 May 2022 | 6,838,458 | samples | 792,638 | 11.6 | 69.1 | 8.0 | [191] | |

| 28 Nov 2022 | 259,366 | samples | 37,483 | 14.5 | 67.3 | 9.7 | [192] | |

| 3 Dec 2022 | 10,578,766 | samples | 696,614 | 6.6 | 674 | 44.4 | [193] | |

| 24 Jul 2021 | 7,417,714 | samples | 1,151,644 | 15.5 | 4.5 | 0.70 | [194] | |

| 14 Oct 2022 | 770,100 | samples | 103,014 | 13.4 | 268 | 35.9 | [195] | |

| 9 May 2022 | 13,217,569 | samples | 982,809 | 7.4 | 139 | 10.4 | [196] | |

| 24 Jan 2023 | 36,548,544 | samples | 4,691,499 | 12.8 | 317 | 40.7 | [197] | |

| 8 Jun 2022 | 572,900 | samples | 60,694 | 10.6 | 140 | 14.9 | [198][199] | |

| 4 May 2021 | 595,112 | samples | 7,884 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 0.067 | [200] | |

| 28 Feb 2022 | 1,736,168 | samples | 12,702 | 0.73 | 234 | 1.71 | [201] | |

| 5 Jun 2022 | 4,358,669 | cases | 910,228 | 20.9 | 38.1 | 8.0 | [202] | |

| 27 Sep 2022 | 1,872,934 | samples | 399,887 | 21.4 | 54.7 | 11.7 | [203] | |

| 11 Jan 2022 | 2,026,898 | 232,432 | 11.5 | 89.9 | 10.3 | [204][205] | ||

| 19 Feb 2021 | 23,561,497 | samples | 10,081,676 | 42.8 | 11.2 | 4.8 | [206][207] | |

| 2 Aug 2021 | 153,804 | samples | 338 | 0.22 | 33.5 | 0.074 | [208] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 10,993,239 | samples | 1,295,524 | 11.8 | 158 | 18.6 | [209] | |

| 4 Mar 2021 | 158,777 | samples | 12,123 | 7.6 | 0.76 | 0.058 | [182][210] | |

| 5 Jan 2021 | 90,019 | 884 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.0074 | [211] | ||

| 1 Aug 2021 | 1,812,706 | 77,914 | 4.3 | 11.2 | 0.48 | [212] | ||

| 18 Feb 2021 | 942,685 | samples | 32,681 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 0.12 | [182] | |

| 26 Nov 2022 | 66,343,123 | samples | 4,423,053 | 6.7 | 175 | 11.7 | [213] | |

| 2 Mar 2021 | 99,027 | samples | 4,020 | 4.1 | 0.72 | 0.029 | [182][214] | |

| 1 Feb 2023 | 48,154,268 | samples | 5,123,007 | 10.6 | 252 | 26.9 | [215] | |

| 31 Jul 2020 | 160,000,000 | cases | 87,655 | 0.055 | 11.1 | 0.0061 | [216][217] | |

| 24 Nov 2022 | 36,875,818 | samples | 6,314,769 | 17.1 | 76.4 | 13.1 | [218][219] | |

| 2 Nov 2021 | 2,575,363 | samples | 561,054 | 21.8 | 51.5 | 11.2 | [220] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 5,481,285 | cases | 1,267,798 | 23.1 | 134 | 31.1 | [221] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 14,301,394 | samples | 1,112,470 | 7.8 | 126 | 9.8 | [222][223] | |

| 29 Jan 2023 | 27,820,163 | samples | 644,160 | 2.3 | 3,223 | 74.4 | [224] | |

| 1 Feb 2023 | 22,544,928 | samples | 4,590,529 | 20.4 | 211 | 42.9 | [225] | |

| 31 Jan 2023 | 67,682,707 | samples | 3,399,947 | 5.0 | 1,162 | 58.4 | [226][227] | |

| 28 Apr 2022 | 305,941 | 15,631 | 5.1 | 33.2 | 1.7 | [228] | ||

| 20 Jun 2022 | 209,803 | cases | 14,821 | 7.1 | 293 | 20.7 | [229] | |

| 22 Jul 2022 | 3,574,665 | samples | 626,030 | 17.5 | 32.9 | 5.8 | [230] | |

| 28 Feb 2021 | 124,838 | 25,961 | 20.8 | 0.14 | 0.029 | [182][231] | ||

| 23 Jul 2021 | 1,627,189 | samples | 480,720 | 29.5 | 9.5 | 2.8 | [232] | |

| 23 Jul 2021 | 3,137,519 | samples | 283,947 | 9.1 | 3.1 | 0.28 | [182][233] | |

| 18 Mar 2022 | 1,847,861 | samples | 161,052 | 8.7 | 28.5 | 2.5 | [234] | |

| 30 Jan 2023 | 403,773 | 17,113 | 4.2 | 30.8 | 1.3 | [235] | ||

| 31 Jan 2023 | 3,637,908 | samples | 613,954 | 16.9 | 274 | 46.2 | [236] | |

| 8 Dec 2021 | 415,110 | 49,253 | 11.9 | 36.5 | 4.3 | [237] | ||

| 24 Jun 2021 | 2,981,185 | samples | 278,446 | 9.3 | 2.6 | 0.24 | [238] | |

| 27 Feb 2022 | 774,000 | samples | 34,237 | 4.4 | 1,493 | 65.7 | [239] | |

| 2 Jan 2023 | 667,953 | samples | 68,848 | 10.3 | 74.5 | 7.7 | [240] | |

| 14 Jan 2022 | 9,042,453 | samples | 371,135 | 4.1 | 163 | 6.7 | [241] | |

| 15 May 2022 | 272,417,258 | samples | 29,183,646 | 10.7 | 417 | 44.7 | [242] | |

| 23 Jul 2021 | 958,807 | samples | 25,325 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 0.082 | [243] | |

| 15 Feb 2021 | 43,217 | samples | 4,469 | 10.3 | 2.0 | 0.21 | [244] | |

| 3 Nov 2021 | 4,888,787 | samples | 732,965 | 15.0 | 132 | 19.7 | [245] | |

| 7 Jul 2021 | 65,247,345 | samples | 3,733,519 | 5.7 | 77.8 | 4.5 | [246][247] | |

| 3 Jul 2021 | 1,305,749 | samples | 96,708 | 7.4 | 4.2 | 0.31 | [248] | |

| 18 Dec 2022 | 101,576,831 | samples | 5,548,487 | 5.5 | 943 | 51.5 | [249] | |

| 30 Jan 2022 | 164,573 | samples | 10,662 | 6.5 | 293 | 19.0 | [250] | |

| 11 May 2021 | 28,684 | 161 | 0.56 | 25.7 | 0.14 | [251] | ||

| 6 Jan 2023 | 6,800,560 | samples | 1,230,098 | 18.1 | 39.4 | 7.1 | [252] | |

| 21 Jul 2021 | 494,898 | samples | 24,878 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 0.19 | [182][253] | |

| 7 Jul 2022 | 145,231 | 8,400 | 5.8 | 7.7 | 0.45 | [254] | ||

| 15 Jun 2022 | 648,569 | cases | 66,129 | 10.2 | 82.5 | 8.4 | [255] | |

| 26 Nov 2022 | 223,475 | cases | 33,874 | 15.2 | 2.0 | 0.30 | [256] | |

| 26 Nov 2021 | 1,133,782 | samples | 377,859 | 33.3 | 11.8 | 3.9 | [257] | |

| 10 May 2022 | 11,394,556 | samples | 1,909,948 | 16.8 | 118 | 19.8 | [258] | |

| 9 Aug 2022 | 1,988,652 | samples | 203,162 | 10.2 | 546 | 55.8 | [259] | |

| 8 Jul 2022 | 866,177,937 | samples | 43,585,554 | 5.0 | 63 | 31.7 | [260][261] | |

| 3 Jul 2023 | 76,062,770 | cases | 6,812,127 | 9.0 | 28.2 | 2.5 | [262][263] | |

| 31 May 2022 | 52,269,202 | samples | 7,232,268 | 13.8 | 62.8 | 8.7 | [264] | |

| 3 Aug 2022 | 19,090,652 | samples | 2,448,484 | 12.8 | 47.5 | 6.1 | [265] | |

| 31 Jan 2023 | 12,990,476 | samples | 1,700,817 | 13.1 | 264 | 34.6 | [266] | |

| 17 Jan 2022 | 41,373,364 | samples | 1,792,137 | 4.3 | 451 | 19.5 | [267] | |

| 16 Mar 2023 | 269,127,054 | samples | 25,651,205 | 9.5 | 446 | 42.5 | [268] | |

| 3 Mar 2021 | 429,177 | samples | 33,285 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 0.13 | [269] | |

| 30 Sep 2022 | 1,184,973 | samples | 151,931 | 12.8 | 43.5 | 5.6 | [270] | |

| 1 Mar 2021 | 8,487,288 | 432,773 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 0.34 | [271] | ||

| 6 Jun 2021 | 7,407,053 | samples | 739,847 | 10.0 | 69.5 | 6.9 | [272] | |

| 28 May 2021 | 11,575,012 | samples | 385,144 | 3.3 | 62.1 | 2.1 | [273] | |

| 5 Mar 2021 | 1,322,806 | samples | 107,729 | 8.1 | 2.8 | 0.23 | [274] | |

| 31 May 2021 | 611,357 | cases | 107,410 | 17.6 | 33.8 | 5.9 | [275] | |

| 9 Mar 2022 | 7,754,247 | samples | 624,573 | 8.1 | 181 | 14.6 | [276] | |

| 10 Feb 2021 | 695,415 | samples | 85,253 | 12.3 | 10.7 | 1.3 | [277] | |

| 1 Mar 2021 | 114,030 | cases | 45 | 0.039 | 1.6 | 0.00063 | [278] | |

| 5 Sep 2021 | 3,630,095 | samples | 144,518 | 4.0 | 189 | 7.5 | [279] | |

| 14 Jun 2021 | 4,599,186 | samples | 542,649 | 11.8 | 67.4 | 8.0 | [280] | |

| 30 Mar 2022 | 431,221 | 32,910 | 7.6 | 21.5 | 1.6 | [281] | ||

| 17 Jul 2021 | 128,246 | 5,396 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 0.11 | [282] | ||

| 14 Apr 2022 | 2,578,215 | samples | 501,862 | 19.5 | 37.6 | 7.3 | [182][283] | |

| 31 Jan 2023 | 9,046,584 | samples | 1,170,108 | 12.9 | 324 | 41.9 | [284][285] | |

| 12 May 2022 | 4,248,188 | samples | 244,182 | 5.7 | 679 | 39.0 | [286] | |

| 19 Feb 2021 | 119,608 | cases | 19,831 | 16.6 | 0.46 | 0.076 | [287] | |

| 29 Nov 2022 | 624,784 | samples | 88,086 | 14.1 | 3.3 | 0.46 | [288] | |

| 7 Sep 2021 | 23,705,425 | cases | 1,880,734 | 7.9 | 72.3 | 5.7 | [289] | |

| 13 Mar 2022 | 2,216,560 | samples | 174,658 | 7.9 | 398 | 31.3 | [290][291] | |

| 7 Jul 2021 | 322,504 | samples | 14,449 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 0.071 | [182][292] | |

| 8 Sep 2021 | 1,211,456 | samples | 36,606 | 3.0 | 245 | 7.4 | [293] | |

| 16 Apr 2021 | 268,093 | 18,103 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 0.41 | [294] | ||

| 22 Nov 2020 | 289,552 | samples | 494 | 0.17 | 22.9 | 0.039 | [295] | |

| 15 Oct 2021 | 10,503,678 | cases | 3,749,860 | 35.7 | 8.2 | 2.9 | [296] | |

| 20 Apr 2022 | 3,213,594 | samples | 516,864 | 16.1 | 122 | 19.6 | [297] | |

| 10 Jul 2021 | 3,354,200 | cases | 136,053 | 4.1 | 100 | 4.1 | [298] | |

| 10 May 2021 | 394,388 | samples | 98,449 | 25.0 | 62.5 | 15.6 | [299][300] | |

| 6 Jan 2023 | 14,217,563 | cases | 1,272,299 | 8.9 | 38.5 | 3.4 | [301] | |

| 22 Jul 2021 | 688,570 | samples | 105,866 | 15.4 | 2.2 | 0.34 | [302] | |

| 16 Sep 2021 | 4,047,680 | samples | 440,741 | 10.9 | 7.4 | 0.81 | [303] | |

| 4 Jul 2022 | 1,062,663 | samples | 166,229 | 15.6 | 38.7 | 6.1 | [304] | |

| 26 Jul 2022 | 5,804,358 | samples | 984,475 | 17.0 | 20.7 | 3.5 | [305] | |

| 6 Jul 2021 | 14,526,293 | cases | 1,692,834 | 11.7 | 83.4 | 9.7 | [306] | |

| 3 Sep 2021 | 41,962 | samples | 136 | 0.32 | 15.7 | 0.050 | [307] | |

| 29 Jan 2023 | 7,757,935 | samples | 2,136,662 | 27.5 | 156 | 42.9 | [308][309] | |

| 22 Feb 2021 | 79,321 | cases | 4,740 | 6.0 | 0.35 | 0.021 | [310] | |

| 28 Feb 2021 | 1,544,008 | samples | 155,657 | 10.1 | 0.75 | 0.076 | [311] | |

| 25 Nov 2020 | 16,914 | cases | 0 | 0 | 0.066 | 0 | [312] | |

| 1 Jul 2021 | 881,870 | samples | 155,689 | 17.7 | 42.5 | 7.5 | [313][314] | |

| 12 Jul 2022 | 7,096,998 | samples | 103,034 | 1.5 | 2,177 | 31.6 | [315] | |

| 20 Jan 2022 | 9,811,888 | samples | 554,778 | 5.7 | 183 | 10.3 | [316] | |

| 28 Oct 2020 | 509,959 | samples | 114,434 | 22.4 | 11.0 | 2.5 | [317] | |

| 5 Mar 2021 | 9,173,593 | samples | 588,728 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 0.27 | [318] | |

| 5 Feb 2022 | 3,078,533 | samples | 574,105 | 18.6 | 60.9 | 11.4 | [319] | |

| 28 Jan 2023 | 7,475,016 | samples | 1,029,701 | 13.8 | 179 | 24.7 | [320] | |

| 17 Feb 2021 | 47,490 | cases | 961 | 2.0 | 0.53 | 0.011 | [321] | |

| 27 Mar 2022 | 2,609,819 | samples | 647,950 | 24.8 | 36.6 | 9.1 | [322] | |

| 17 Nov 2022 | 36,073,768 | samples | 4,177,786 | 11.6 | 109.9 | 12.7 | [323] | |

| 7 Jan 2023 | 34,402,980 | samples | 4,073,980 | 11.8 | 34.1 | 4.0 | [324][325] | |

| 27 Apr 2022 | 36,064,311 | samples | 5,993,861 | 16.6 | 94.0 | 15.6 | [326] | |

| 5 Jan 2022 | 27,515,490 | samples | 1,499,976 | 5.5 | 268 | 14.6 | [327] | |

| 11 Nov 2022 | 4,061,988 | cases | 473,440 | 11.7 | 141 | 16.4 | [328] | |

| 29 Jan 2021 | 5,405,393 | samples | 724,250 | 13.4 | 27.9 | 3.7 | [329] | |

| 6 Jun 2022 | 295,542,733 | samples | 18,358,459 | 6.2 | 201 | 12.5 | [330][331] | |

| 6 Oct 2021 | 2,885,812 | samples | 98,209 | 3.4 | 22.3 | 0.76 | [332] | |

| 26 Aug 2021 | 30,231 | cases | 995 | 3.3 | 57.6 | 1.9 | [333] | |

| 7 Oct 2022 | 212,132 | samples | 29,550 | 13.9 | 116.6 | 16.2 | [334] | |

| 28 Jan 2023 | 113,504 | cases | 9,585 | 8.4 | 103.0 | 8.7 | [335] | |

| 29 Jan 2023 | 192,613 | samples | 23,427 | 12.2 | 563 | 68.4 | [336] | |

| 26 Apr 2022 | 41,849,069 | samples | 753,632 | 1.8 | 120 | 2.2 | [337] | |

| 12 Jul 2021 | 624,502 | samples | 46,509 | 7.4 | 3.9 | 0.29 | [338] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 12,185,475 | cases | 2,473,599 | 20.3 | 175 | 35.5 | [339] | |

| 3 Aug 2021 | 16,206,203 | samples | 65,315 | 0.40 | 284 | 1.1 | [340][341] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 7,391,882 | samples | 1,861,034 | 25.2 | 135 | 34.1 | [342] | |

| 2 Feb 2023 | 2,826,117 | samples | 1,322,282 | 46.8 | 135 | 63.1 | [343] | |

| 24 May 2021 | 11,378,282 | cases | 1,637,848 | 14.4 | 19.2 | 2.8 | [344][345] | |

| 1 Mar 2021 | 6,592,010 | samples | 90,029 | 1.4 | 12.7 | 0.17 | [346] | |

| 26 May 2021 | 164,472 | 10,688 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 0.084 | [347] | ||

| 1 Jul 2021 | 54,128,524 | samples | 3,821,305 | 7.1 | 116 | 8.2 | [348][349] | |

| 30 Mar 2021 | 2,384,745 | samples | 93,128 | 3.9 | 10.9 | 0.43 | [350][351] | |

| 7 Jan 2021 | 158,804 | samples | 23,316 | 14.7 | 0.36 | 0.053 | [182] | |

| 24 May 2021 | 9,996,795 | samples | 1,074,751 | 10.8 | 96.8 | 10.4 | [352][353] | |

| 7 Nov 2022 | 23,283,909 | samples | 4,276,836 | 18.4 | 270 | 49.7 | [354] | |

| 3 Feb 2023 | 30,275,725 | samples | 8,622,129 | 28.48 | 128.3 | 36.528 | [355] | |

| 18 Nov 2020 | 3,880 | 509 | 13.1 | 0.0065 | 0.00085 | [182] | ||

| 4 Mar 2021 | 1,579,597 | cases | 26,162 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 0.038 | [356] | |

| 6 Jan 2023 | 807,269 | 39,358 | 4.9 | 9.4 | 0.46 | [357] | ||

| 3 Jan 2022 | 512,730 | cases | 92,997 | 18.1 | 37.6 | 6.8 | [358] | |

| 23 Aug 2021 | 2,893,625 | samples | 703,732 | 24.3 | 24.5 | 6.0 | [359] | |

| 2 Jul 2021 | 61,236,294 | samples | 5,435,831 | 8.9 | 73.6 | 6.5 | [360] | |

| 11 Feb 2021 | 852,444 | samples | 39,979 | 4.7 | 1.9 | 0.087 | [361] | |

| 24 Nov 2021 | 15,648,456 | samples | 3,367,461 | 21.5 | 37.2 | 8.0 | [362] | |

| 1 Feb 2023 | 198,685,717 | samples | 1,049,537 | 0.53 | 2,070 | 10.9 | [363] | |

| 19 May 2022 | 522,526,476 | samples | 22,232,377 | 4.3 | 774 | 32.9 | [364] | |

| 29 Jul 2022 | 929,349,291 | samples | 90,749,469 | 9.8 | 281 | 27.4 | [365][366] | |

| 16 Apr 2022 | 6,089,116 | samples | 895,592 | 14.7 | 175 | 25.8 | [367] | |

| 7 Sep 2020 | 2,630,000 | samples | 43,975 | 1.7 | 7.7 | 0.13 | [368] | |

| 30 Mar 2021 | 3,179,074 | samples | 159,149 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 0.55 | [369] | |

| 28 Aug 2022 | 45,772,571 | samples | 11,403,302 | 24.9 | 46.4 | 11.6 | [370] | |

| 10 Mar 2022 | 3,301,860 | samples | 314,850 | 9.5 | 19.0 | 1.8 | [371] | |

| 15 Oct 2022 | 2,529,087 | samples | 257,893 | 10.2 | 17.0 | 1.7 | [182][372] | |

| ||||||||

Virus testing statistics by country subdivision

Template:COVID-19 testing by country subdivision

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

This article incorporates public domain material from Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b Abbasi, Jennifer (17 April 2020). "The Promise and Peril of Antibody Testing for COVID-19". JAMA. JAMA Network. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6170. PMID 32301958. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Ioannidis, John P.A. (17 March 2020). "A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data". STAT. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Total tests for COVID-19 per 1,000 people". Our World in Data. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Iceland has tested more of its population for coronavirus than anywhere else. Here's what it learned". USA Today. 11 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ a b Ward, D. (April 2020) "Sampling Bias: Explaining Wide Variations in COVID-19 Case Fatality Rates". WardEnvironment.

- ^ Henriques, Martha. "Coronavirus: Why death and mortality rates differ". bbc.com. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Michaels, Jonathan A.; Stevenson, Matt D. (2020). "Explaining national differences in the mortality of Covid-19: Individual patient simulation model to investigate the effects of testing policy and other factors on apparent mortality" (Document). doi:10.1101/2020.04.02.20050633.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Siouxsie Wiles & Toby Morris: What we don't know about Covid-19". The Spinoff. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "How is the COVID-19 Virus Detected using Real Time RT-PCR?". IAEA. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "RNA Extraction". AssayGenie. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Bustin, Stephen A.; Benes, Vladimir; Garson, Jeremy A.; Hellemans, Jan; Huggett, Jim; Kubista, Mikael; Mueller, Reinhold; Nolan, Tania; Pfaffl, Michael W.; Shipley, Gregory L.; Vandesompele, Jo; Wittwer, Carl T. (1 April 2009). "The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments". Clinical Chemistry. pp. 611–622. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797.

- ^ "Real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and its potential use in clinical diagnosis" (PDF). Clinical Science. 23 September 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "The Basics: RT-PCR". ThermoFisher Scientific. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Kang XP, Jiang T, Li YQ, et al. (2010). "A duplex real-time RT-PCR assay for detecting H5N1 avian influenza virus and pandemic H1N1 influenza virus". Virol. J. 7: 113. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-7-113. PMC 2892456. PMID 20515509.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Joyce C (2002). Quantitative RT-PCR. A review of current methodologies. Methods Mol. Biol. Vol. 193. pp. 83–92. doi:10.1385/1-59259-283-X:083. ISBN 978-1-59259-283-8. PMID 12325527.

- ^ Varkonyi-Gasic E, Hellens RP (2010). "qRT-PCR of Small RNAs". Plant Epigenetics. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 631. pp. 109–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-646-7_10. ISBN 978-1-60761-645-0. PMID 20204872.

- ^ "ACCELERATED EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) SUMMARY COVID-19 RT-PCR TEST (LABORATORY CORPORATION OF AMERICA)". FDA. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Taylor S, Wakem M, Dijkman G, Alsarraj M, Nguyen M (April 2010). "A practical approach to RT-qPCR-Publishing data that conform to the MIQE guidelines". Methods. 50 (4): S1–5. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.005. PMID 20215014.

- ^ "Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-nCoV". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Here's where things stand on COVID-19 tests in the U.S." ScienceNews. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Curetis Group Company Ares Genetics and BGI Group Collaborate to Offer Next-Generation Sequencing and PCR-based Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Testing in Europe". GlobeNewswire News Room. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Drosten, Christian (26 March 2020). "Coronavirus-Update Folge 22" (PDF). NDR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Saliva: potential diagnostic value and transmission of 2019-nCoV". Nature. 17 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b "FDA authorizes Covid-19 saliva test for emergency use". CNN. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ a b "New Rutgers Saliva Test for Coronavirus Gets FDA Approval". Rutgers.edu. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 saliva tests: What is the benefit?". Mayo Clinic. 16 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Yale University School of Public Health finds saliva samples promising alternative to nasopharyngeal swab". Merck Manual. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Wyllie, Anne Louise; Fournier, John; Casanovas-Massana, Arnau; Campbell, Melissa; Tokuyama, Maria; Vijayakumar, Pavithra; Geng, Bertie; Muenker, M. Catherine; Moore, Adam J.; Vogels, Chantal B. F.; Petrone, Mary E.; Ott, Isabel M.; Lu, Peiwen; Lu-Culligan, Alice; Klein, Jonathan; Venkataraman, Arvind; Earnest, Rebecca; Simonov, Michael; Datta, Rupak; Handoko, Ryan; Naushad, Nida; Sewanan, Lorenzo R.; Valdez, Jordan; White, Elizabeth B.; Lapidus, Sarah; Kalinich, Chaney C.; Jiang, Xiaodong; Kim, Daniel J.; Kudo, Eriko; Linehan, Melissa (22 April 2020). "Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection in COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs" (Document). Medrxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.04.16.20067835.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f "Developing Antibodies and Antigens for COVID-19 Diagnostics". Technology Networks. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ a b "NIH launches competition to speed COVID-19 diagnostics". AAAS. 29 April 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.