Anticonvulsant

The anticonvulsants are a diverse group of pharmaceuticals used in the treatment of epileptic seizures. Anticonvulsants are also increasingly being used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, since many seem to act as mood stabilizers. The goal of an anticonvulsant is to suppress the rapid and excessive firing of neurons that start a seizure. Because of this, anticonvulsants also have proven effective in treating many kinds of dysfunctional anxiety. Failing this, an effective anticonvulsant would prevent the spread of the seizure within the brain and offer protection against possible excitotoxic effects that may result in brain damage. However, anticonvulsants themselves have been linked to lowered IQ in children.[1] Anticonvulsants are often called antiepileptic drugs (abbreviated "AEDs"), although antiseizure drugs may be more appropriate since no AED has been shown to be disease modifying.

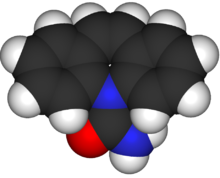

The major molecular targets of marketed anticonvulsant drugs are voltage-gated sodium channels and components of the GABA system, including GABAA receptors, the GAT-1 GABA transporter, and GABA transaminase.[2] Additional targets include voltage-gated calcium channels, SV2A, and α2δ. [3][4].

Some anticonvulsants have shown antiepileptogenic effects in animal models of epilepsy. That is, they either prevent the expected development of epilepsy or can halt or reverse the progression of epilepsy. However, no drug has been shown to prevent epileptogenesis (the development of epilepsy after an injury such as a head injury) in human trials.[5]

Approval

The usual method of achieving approval for a drug is to show it is effective when compared against placebo, or that it is more effective than an existing drug. In monotherapy (where only one drug is taken) it is considered unethical by most to conduct a trial with placebo on a new drug of uncertain efficacy. This is because untreated epilepsy leaves the patient at significant risk of death. Therefore, almost all new epilepsy drugs are initially approved only as adjunctive (add-on) therapies. Patients whose epilepsy is currently uncontrolled by their medication (i.e., it is refractory to treatment) are selected to see if supplementing the medication with the new drug leads to an improvement in seizure control. Any reduction in the frequency of seizures is compared against a placebo.[5]

Once there is confidence that a drug is likely to be effective in monotherapy, trials are conducted where the drug is compared to an existing standard. For partial-onset seizures, this is typically carbamazepine. Despite the launch of over ten drugs since 1990, no new drug has been shown to be more effective than the older set, which includes carbamazepine, valproate and phenytoin. The lack of superiority over existing treatment, combined with lacking placebo-controlled trials, means that few modern drugs have earned FDA approval as initial monotherapy. In contrast, Europe only requires equivalence to existing treatments, and has approved many more. Despite their lack of FDA approval, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society still recommend a number of these new drugs as initial monotherapy.[5]

Drugs

In the following list, the dates in parentheses are the earliest approved use of the drug.

Aldehydes

Main article: Aldehydes

- Paraldehyde (1882). One of the earliest anticonvulsants. Still used to treat status epilepticus, particularly where there are no resuscitation facilities.

Aromatic allylic alcohols

- Stiripentol (2001 - limited availability). Indicated for the treatment of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI).

Barbiturates

Main article: Barbiturates

Barbiturates are drugs that act as central nervous system (CNS) depressants, and by virtue of this they produce a wide spectrum of effects, from mild sedation to anesthesia. The following are classified as anticonvulsants:

- Phenobarbital (1912). See also the related drug primidone.

- Methylphenobarbital (1935). Known as mephobarbital in the US. No longer marketed in the UK

- Metharbital (1952). No longer marketed in the UK or US.

- Barbexaclone (1982). Only available in some European countries.

Phenobarbital was the main anticonvulsant from 1912 till the development of phenytoin in 1938. Today, phenobarbital is rarely used to treat epilepsy in new patients since there are other effective drugs that are less sedating. Phenobarbital sodium injection can be used to stop acute convulsions or status epilepticus, but a benzodiazepine such as lorazepam, diazepam or midazolam is usually tried first. Other barbiturates only have an anticonvulsant effect at anaesthetic doses.

Benzodiazepines

Main article: Benzodiazepines

The benzodiazepines are a class of drugs with hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsive, amnestic and muscle relaxant properties. Benzodiazepines act as a central nervous system depressant. The relative strength of each of these properties in any given benzodiazepine varies greatly and influences the indications for which it is prescribed. Long-term use can be problematic due to the development of tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects and dependency.[6][7][8][9] Of the many drugs in this class, only a few are used to treat epilepsy:

- Clobazam (1979). Notably used on a short-term basis around menstruation in women with catamenial epilepsy.

- Clonazepam (1974).

- Clorazepate (1972).

The following benzodiazepines are used to treat status epilepticus:

- Diazepam (1963). Can be given rectally by trained care-givers.

- Midazolam (N/A). Increasingly being used as an alternative to diazepam. This water-soluble drug is squirted into the side of the mouth but not swallowed. It is rapidly absorbed by the buccal mucosa.

- Lorazepam (1972). Given by injection in hospital.

Nitrazepam, temazepam, and especially nimetazepam are powerful anticonvulsant agents, however their use is rare due to an increased incidence of side effects and strong sedative and motor-impairing properties.

Bromides

Main article: Bromides

- Potassium bromide (1857). The earliest effective treatment for epilepsy. There would not be a better drug for epilepsy until phenobarbital in 1912. It is still used as an anticonvulsant for dogs and cats.

Carbamates

Main article: Carbamates

- Felbamate (1993). This effective anticonvulsant has had its usage severely restricted due to rare but life-threatening side effects.

Carboxamides

Main article: Carboxamides

The following are carboxamides:

- Carbamazepine (1963). A popular anticonvulsant that is available in generic formulations.

- Oxcarbazepine (1990). A derivative of carbamazepine that has similar efficacy but is better tolerated and is also available generically.

- Eslicarbazepine acetate (2009)

Fatty acids

Main article: Fatty acids

The following are fatty-acids:

- The valproates — valproic acid, sodium valproate, and divalproex sodium (1967).

- Vigabatrin (1989).

- Progabide

- Tiagabine (1996).

Vigabatrin and progabide are also analogs of GABA.

Fructose derivatives

- Topiramate (1995).

Gaba analogs

- Gabapentin (1993).

- Pregabalin (2004).

Hydantoins

Main article: Hydantoins

The following are hydantoins:

- Ethotoin (1957).

- Phenytoin (1938).

- Mephenytoin

- Fosphenytoin (1996).

Oxazolidinediones

Main article: Oxazolidinediones

The following are oxazolidinediones:

- Paramethadione

- Trimethadione (1946).

- Ethadione

Propionates

Main article: Propionates

Pyrimidinediones

Main article: Pyrimidinediones

- Primidone (1952).

Pyrrolidines

Main article: Pyrrolidines

- Brivaracetam

- Levetiracetam (1999).

- Seletracetam

Succinimides

Main article: Succinimides

The following are succinimides:

- Ethosuximide (1955).

- Phensuximide

- Mesuximide

Sulfonamides

Main article: Sulfonamides

- Acetazolamide (1953).

- Sultiame

- Methazolamide

- Zonisamide (2000).

Triazines

Main article: Triazines

- Lamotrigine (1990).

Ureas

Main article: Ureas

Valproylamides (amide derivatives of valproate)

Main article: Amides

Diet

The ketogenic diet is a strict medically supervised diet that has an anticonvulsant effect. It is typically used in children with refractory epilepsy.

Devices

The vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) is a device that sends electric impulses to the left vagus nerve in the neck via a lead implanted under the skin. It was FDA approved in 1997 as an adjunctive therapy for partial-onset epilepsy.

Marketing approval history

The following table lists anticonvulsant drugs together with the date their marketing was approved in the US, UK and France. Data for the UK and France are incomplete. In recent years, the European Medicines Agency has approved drugs throughout the European Union. Some of the drugs are no longer marketed.

| Drug | Brand | US | UK | France |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetazolamide | Diamox | 27 July 1953[10] | 1988[11] | |

| carbamazepine | Tegretol | 15 July 1974[12][13] | 1965[11] | 1963[14] |

| clobazam | Frisium | 1979[11] | ||

| clonazepam | Klonopin/Rivotril | 4 June 1975[15] | 1974[11] | |

| diazepam | Valium | 15 November 1963[16] | ||

| divalproex sodium | Depakote | 10 March 1983[17] | ||

| ethosuximide | Zarontin | 2 November 1960[18] | 1955[11] | 1962[14] |

| ethotoin | Peganone | 22 April 1957[19] | ||

| felbamate | Felbatol | 29 July 1993[20] | ||

| fosphenytoin | Cerebyx | 5 August 1996[21] | ||

| gabapentin | Neurontin | 30 December 1993[22] | May 1993[11][14] | October 1994[14] |

| lamotrigine | Lamictal | 27 December 1994[23] | October 1991[11][14] | May 1995[14] |

| levetiracetam | Keppra | 30 November 1999[24] | 29 September 2000[11][25] | 29 September 2000[25] |

| mephenytoin | Mesantoin | 23 October 1946[26] | ||

| metharbital | Gemonil | 1952[27][28] | ||

| methsuximide | Celontin | 8 February 1957[29] | ||

| methazolamide | Neptazane | 26 January 1959[30] | ||

| oxcarbazepine | Trileptal | 14 January 2000[31] | 2000[11] | |

| phenobarbital | 1912[11] | 1920[14] | ||

| phenytoin | Dilantin/Epanutin | 1938[14][32] | 1938[11] | 1941[14] |

| phensuximide | Milontin | 1953[33][34] | ||

| pregabalin | Lyrica | 30 December 2004[35] | 6 July 2004[11][36] | 6 July 2004[36] |

| primidone | Mysoline | 8 March 1954[37] | 1952[11] | 1953[14] |

| sodium valproate | Epilim | December 1977[14] | June 1967[14] | |

| stiripentol | Diacomit | 5 December 2001[38] | 5 December 2001[38] | |

| tiagabine | Gabitril | 30 September 1997[39] | 1998[11] | November 1997[14] |

| topiramate | Topamax | 24 December 1996[40] | 1995[11] | |

| trimethadione | Tridione | 25 January 1946[41] | ||

| valproic acid | Depakene/Convulex | 28 February 1978[42] | 1993[11] | |

| vigabatrin | Sabril | 21 August 2009[43] | 1989[11] | |

| zonisamide | Zonegran | 27 March 2000[44] | 10 March 2005[11][45] | 10 March 2005[45] |

See also

References

- ^ Loring, David W (1 September 2005). "Cognitive Side Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs in Children". Psychiatric Times. XXII (10).

- ^ Rogawski MA, Löscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004 Jul;5(7):553-564. PMID 15208697

- ^ Rogawski MA, Bazil CW. New molecular targets for antiepileptic drugs: α2δ, SV2A, and K(v)7/KCNQ/M potassium channels. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008 Jul;8(4):345-352. PMID 18590620

- ^ Meldrum BS, Rogawski MA. Molecular targets for antiepileptic drug development. Neurotherapeutics. 2007 Jan;4(1):18-61. PMID 17199015

- ^ a b c Abou-Khalil BW (2007). "Comparative monotherapy trials and the clinical treatment of epilepsy". Epilepsy currents / American Epilepsy Society. 7 (5): 127–9. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00198.x. PMC 2043140. PMID 17998971.

- ^ Browne TR (1976). "Clonazepam. A review of a new anticonvulsant drug". Arch Neurol. 33 (5): 326–32. PMID 817697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Isojärvi, JI (1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". J Intellect Disabil Res. 42 (1): 80–92. PMID 10030438.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tomson T (1986). "Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: high incidence of complex partial status". Epilepsia. 27 (3): 276–85. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03540.x. PMID 3698940.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Djurić, M (2001). "[West syndrome--new therapeutic approach]". Srp Arh Celok Lek. 129 (1): 72–7. PMID 15637997.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ NDA 008943

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Epilepsy Action: Druglist. Retrieved on 1 November 2007.

- ^ NDA 016608 (Initial approval on 11 March 1968 was for trigeminal neuralgia.)

- ^ Schain, Richard J. (1 March 1978). "Pediatrics—Epitomes of Progress: Carbamazepine (Tegretol) in the Treatment of Epilepsy". Western Journal of Medicine. 128 (3): 231–232. PMC 1238063. PMID 18748164. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Loiseau, Pierre Jean-Marie (1999). "Clinical Experience with New Antiepileptic Drugs: Antiepileptic Drugs in Europe" (PDF). Epilepsia. 40 (Suppl 6): S3–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00925.x. PMID 10530675. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ NDA 017533

- ^ NDA 013263

- ^ NDA 018723

- ^ NDA 012380

- ^ NDA 010841

- ^ NDA 020189

- ^ NDA 020450

- ^ NDA 020235

- ^ NDA 020241

- ^ NDA 021035

- ^ a b EPAR: Keppra. Retrieved on 1 November 2007.

- ^ NDA 006008

- ^ NDA 008322

- ^ Dodson, W. Edwin; Giuliano Avanzini; Shorvon, Simon D.; Fish, David R.; Emilio Perucca (2004). The treatment of epilepsy. Oxford: Blackwell Science. xxviii. ISBN 0-632-06046-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NDA 010596

- ^ NDA 011721

- ^ NDA 021014

- ^ NDA 008762 (Marketed in 1938, approved 1953)

- ^ NDA 008855

- ^ Kutt, Henn; Resor, Stanley R. (1992). The Medical treatment of epilepsy. New York: Dekker. p. 385. ISBN 0-8247-8549-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (first usage) - ^ NDA 021446

- ^ a b EPAR: Lyrica Retrieved on 1 November 2007.

- ^ NDA 009170

- ^ a b EPAR: Diacomit. Orphan designation: 5 December 2001, full authorisation: 4 January 2007 Retrieved on 1 November 2007.

- ^ NDA 020646

- ^ NDA 020505

- ^ NDA 005856

- ^ NDA 018081

- ^ Lundbeck Press Release

- ^ NDA 020789

- ^ a b EPAR: Zonegran. Retrieved on 1 November 2007