History of Newcastle, New South Wales

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

Archaeological evidence indicates that human beings have inhabited the area around Newcastle, New South Wales for at least 6500 years. In 2009, archaeologist uncovered over 5,534 Aboriginal artefacts, representing three occupation periods.[1] In the 1820s, the Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld worked with local Awabakal man Biraban to record the Awabakal language.[2] Since 1892, the Indigenous people of Newcastle have come to be known as the Awabakal.

The first European to explore the area was Lieutenant John Shortland in September 1797. He had been sent in search of convicts who had seized HMS Cumberland sailing from Sydney Cove.[3] On his return, Lt. Shortland entered "a very fine coal river", which he named after New South Wales' Governor, John Hunter.[4] The coal mined from the area was the New South Wales colony's first export.[4] Newcastle gained a reputation as a "hellhole" as it was where the most dangerous convicts were sent to dig in the coal mines as punishment.[4]

Newcastle remained a penal settlement until 1822, when the settlement was opened up to farming.[5] Military rule ended in 1823 and prisoner numbers were reduced to 100 while the remaining 900 were sent to Port Macquarie.[4] After the town was freed from the influence of penal law it began to acquire the aspect of a typical Australian pioneer settlement, and free settlers soon poured into the hinterland.

Today, the Port of Newcastle remains the economic and trade centre for the resource rich Hunter Valley. It is the world's largest coal export port and Australia's oldest and second largest tonnage throughput port. The old central business district contains a considerable number of historic buildings, dominated by Christ Church Cathedral. Other noteworthy buildings include Fort Scratchley, the Ocean Baths, the old Customs House, the 1920s City Hall, the 1890s Longworth Institute, and the 1930s art deco University House.

Pre-European settlement

The Awabakal, Worimi, Wonnarua, Geawegal, Birrpai and Darkinjung peoples are the traditional owners of the land that now makes up the lower Hunter Region.[6] The Awabakal people called the area Mulubinba, after an indigenous fern called the mulubin. Archaeological evidence indicates that human beings have inhabited the landscape of Newcastle for at least 6500 years. In 2009, archaeologist uncovered artefacts including a hearth and factory at the site of the former Palais Royale on Hunter Street. Over 5,534 Aboriginal artefacts were recovered, representing three occupation periods dating from 6,716 - 6,502 years BP (before present). This site was identified as a site of ‘high to exceptional cultural and scientific significance’.[1] Over the millennia, the artefacts manufactured there, on what came to be known as Cottage Creek, were probably traded across the region, and across many territories or countries.

The Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, a missionary stationed at Newcastle and Lake Macquarie during the 1820s onwards, recorded that the Aboriginal people of the Newcastle Tribe were called Mulubinbakal (men) and Mulubinbakalleen (female). Threlkled worked with local Awabakal man Biraban to record the Awabakal language.[2] Since 1892, the Indigenous people of Newcastle have come to be known as the Awabakal.[7]

Founding and settlement by Europeans

The first European to explore the area was Lieutenant John Shortland in September 1797. His discovery of the area was largely accidental; as he had been sent in search of a number of convicts who had seized HMS Cumberland as she was sailing from Sydney Cove.[3]

While returning, Lt. Shortland entered what he later described as "a very fine coal river", which he named after New South Wales' Governor, John Hunter.[4] He returned with reports of the deep-water port and the area's abundant coal. Over the next two years, coal mined from the area was the New South Wales colony's first export.[4]

Newcastle gained a reputation as a "hellhole" as it was a place where the most dangerous convicts were sent to dig in the coal mines as harsh punishment for their crimes.[4]

By the turn of the century the mouth of the Hunter River was being visited by diverse groups of men, including coal diggers, timber-cutters, and more escaped convicts. Philip Gidley King, the Governor of New South Wales from 1800, decided on a more positive approach to exploit the now obvious natural resources of the Hunter Valley.[3]

In 1801, a convict camp called King's Town (named after Governor King) was established to mine coal and cut timber. In the same year, the first shipment of coal was dispatched to Sydney. This settlement closed less than a year later.[4]

A settlement was again attempted in 1804, as a place of secondary punishment for unruly convicts. The settlement was named Coal River, also Kingstown and then renamed Newcastle, after England's famous coal port. The name first appeared by the commission issued by Governor King on 15 March 1804 to Lieutenant Charles Menzies of the Royal Marines, appointing him superintendent of the new settlement.[8]

The new settlement, comprising convicts and a military guard, arrived at the Hunter River on 27 March 1804 in three ships: HMS Lady Nelson, the Resource and the James.[3][9] The convicts were rebels from the 1804 Castle Hill convict rebellion.

The link with Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, its namesake and also from whence many of the 19th century coal miners came, is still obvious in some of the place-names – such as Jesmond, Hexham, Wickham, Wallsend and Gateshead. Morpeth, New South Wales is a similar distance north of Newcastle as Morpeth, Northumberland is north of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Under Captain James Wallis, commandant from 1816 to 1818, the convicts' conditions improved, and a building boom began. Captain Wallis laid out the streets of the town, built the first church of the site of the present Christ Church Anglican Cathedral, erected the old gaol on the seashore, and began work on the breakwater which now joins Nobbys Head to the mainland. The quality of these first buildings was poor, and only (a much reinforced) breakwater survives. During this period, in 1816, the oldest public school in Australia was built in Newcastle East.[4]

Newcastle remained a penal settlement until 1822, when the settlement was opened up to farming.[5] As a penal colony, the military rule was harsh, especially at Limeburners' Bay, on the inner side of Stockton peninsula. There, convicts were sent to burn oyster shells for making lime.[3]

Military rule in Newcastle ended in 1823. Prisoner numbers were reduced to 100 (most of these were employed on the building of the breakwater), and the remaining 900 were sent to Port Macquarie.[4]

Civilian government

After removal of the last convicts in 1823, the town was freed from the infamous influence of the penal law. It began to acquire the aspect of a typical Australian pioneer settlement, and a steady flow of free settlers poured into the hinterland.

Early steamers

The formation during the nineteenth century of the Newcastle & Hunter River Steamship Company[10] saw the establishment of regular steamship services from Morpeth and Newcastle with Sydney. The company had a fleet of freighters as well as several fast passenger vessels, including PS Newcastle and PS Namoi. Namoi had first-class cabins with the latest facilities. Passengers on overnight passage to Sydney arrived fresh for the new day, and was preferable to the long and arduous railway journey.[11]

Because of the coal supply, small ships plied between Newcastle and Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne and Adelaide, carrying coal to gas works and bunkers for shipping, and railways. These were commonly known as sixty-milers, referring to the nautical journey between Newcastle and Sydney. These ships continued in service until recent times.[12][13]

World War II

During World War II, Newcastle was an important industrial centre for the Australian war effort.

In the early hours of 8 June 1942, the Japanese submarine I-21 briefly shelled Newcastle. Among the areas hit within the city were dockyards, the steel works, Parnell Place in the city's now affluent East End, the breakwall and Art Deco ocean baths. There were no casualties in the attack and damage was minimal.[14]

Economic history

Coal

Coal mining began in earnest in the 1830s, with collieries working close to the city itself and others within a 16 km (10 mi) radius.[citation needed] Most of Newcastle's principal coal mines (Stockton, Tighes Hill, Carrington, the Australian Agricultural Company, the Newcastle Coal Mining company's big collieries at Merewether (includes the Glebe), Wallsend, and the Waratah collieries), had all closed by the early 1960s. They had been replaced over four decades by the larger coal mining activities further inland at places such as Kurri Kurri and Cessnock.[citation needed]

On 10 December 1831, the Australian Agricultural Company officially opened Australia's first railway to carry export coal from near the Anglican Cathedral at Newcastle to the wharf area.[15]

Copper

In the 1850s, a major copper smelting works was established at Burwood, near Merewether. An engraving of this appeared in the Illustrated London News on 11 February 1854.[citation needed] The English and Australian Copper Company built another substantial works at Broadmeadow circa 1890, and in that decade a zinc smelter was built by Sulphide Corporation inland, by Cockle Creek, known as the Cockle Creek Smelter.

Soap

The largest factory of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere was constructed in 1885, on a 8.9 ha (22-acre) site between the suburbs of Tighes Hill and Port Waratah, by Charles Upfold, from London, for his Sydney Soap and Candle Company, to replace a smaller factory in Wickham.[16] Their soap products won 17 medals at International Exhibitions. At the Sydney International Exhibition they won a bronze medal "against all-comers from every part of the world", the only first prize awarded for soap and candles. Following World War I the company was sold to Messrs Lever & Kitchen (today Lever Bros), and the factory closed in the mid-1930s.

Steel

In 1911, BHP chose the city as the site for its steelworks due to the abundance of coal.[4] The land put aside was prime real estate, on the southern edge of the harbour. In 1915, the BHP steelworks opened, beginning a period of some 80 years dominating the steel works and heavy industry. As Mayfield and the suburbs surrounding the steelworks declined in popularity because of pollution, the steelworks thrived, becoming the region's largest employer.

In 1999, the steelworks closed after 84 years operation and had employed about 50,000 in its existence, many for decades.[17]

Disasters

1989 Newcastle earthquake

On 28 December 1989, Newcastle experienced an earthquake measuring 5.6 on the Richter scale, which killed 13 people, injured 160 and destroyed or severely damaged a number of prominent buildings. Some had to be demolished, including the large George Hotel in Scott Street (city), the Century Theatre at Broadmeadow, the Hunter Theatre (formerly 'The Star'), the Newcastle RSL in Perkins Street, and the majority of The Junction school at Merewether. Part of the Newcastle Workers' Club, a popular venue, was destroyed and later replaced by a new structure. The city and suburbs suffered significant property damage also. The following economic recession of the early 1990s meant that the city took several years to recover.

June 2007 Hunter Region and Central Coast storms

On 8 June 2007 the Hunter and Central Coast regions were battered by the worst series of storms to hit New South Wales in 30 years. This resulted in extensive flooding and nine deaths. Thousands of homes were flooded and many were destroyed.[18][19] The Hunter and Central Coast regions were declared natural disaster areas by the Premier, Morris Iemma, on 8 June 2007 .[20] Further flooding was predicted by the Bureau of Meteorology but was less severe than predicted.

During the early stages of the storms the 225-metre (738 ft)-long bulk carrier ship, MV Pasha Bulker, ran aground at Nobby's Beach after failing to heed warnings to move offshore. Pasha Bulker was finally refloated on the third salvage attempt on 2 July 2007 despite earlier fears that the ship would break up. After initially entering the port for minor repairs it departed for major repairs in Asia under tow on 26 July 2007.

Maritime

The most tragic maritime accident of the twentieth-century in Newcastle occurred on 9 August 1934 when the Stockton-bound ferry Bluebell collided with the coastal freighter, Waraneen, and sank in the middle of the Hunter River.[21] The Bluebell Collision claimed three lives and fifteen passengers were admitted to the Newcastle Hospital, with two suffering severely from the effects of immersion. It was later found that the ferry pilot was at fault.[22]

Aviation

On 16 August 1966, a Royal Australian Air Force F-86 Sabre crashed into the inner city suburb of The Junction.[23] The pilot, Flying Officer Warren William Goddard, experienced engine troubles and unsuccessfully tried to fly the plane out to the Pacific Ocean. He ejected but his parachute failed to fully deploy and he was killed when he crashed through the roof of a house. Although The Junction is a highly populated suburb of Newcastle and most of the plane wreckage landed in the shopping area of the suburb, nobody was killed or injured by the aircraft wreckage. In 2007 a memorial plaque was unveiled for the killed pilot.[23]

Modern era

The Port of Newcastle remains the economic and trade centre for the resource rich Hunter Valley and for much of the north and northwest of New South Wales. Newcastle is the world's largest coal export port and Australia's oldest and second largest tonnage throughput port, with over 3,000 shipping movements handling cargo of 93,000,000 tonnes (92,000,000 long tons; 103,000,000 short tons) per annum, of which coal exports represented 88,880,000 tonnes (87,480,000 long tons; 97,970,000 short tons) in 2007/08.[24] The volume of coal exported, and attempts to increase coal exports, are opposed by environmental groups.[25][26]

Newcastle has a small shipbuilding industry, which has declined since the 1970s.[27] In recent years the only major ship-construction contract awarded to the area was the construction of the Huon-class minehunters.[28]

The era of extensive heavy industry passed when the steel works closed in 1999. Many of the remaining manufacturing industries have located themselves well away from the city itself, focusing on cheap land and access to road transport routes and lack the concentrated social impact of BHP on the city's life.

Newcastle has one of the oldest theatre districts in Australia. Victoria Theatre on Perkins Street is the oldest purpose-built theatre in the country. The old city centre has seen some new apartments and hotels built in recent years, but the rate of commercial and retail occupation remains low while alternate suburban centres have become more important. The CBD itself is shifting to the west, towards the major urban renewal area known as Honeysuckle. This renewal is a major part of arresting the shift of business and residents to the suburbs.

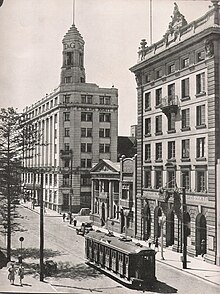

The old central business district, located at Newcastle's eastern end, still has a considerable number of historic buildings, dominated by Christ Church Cathedral, seat of the (Anglican) Bishop of Newcastle.[29] Other noteworthy buildings include Fort Scratchley, the Ocean Baths, the old Customs House, the 1920s City Hall, the 1890s Longworth Institute (once regarded as the finest building in the colony) and the 1930s art deco University House (formerly NESCA House, recently seen in the film Superman Returns). Residents of Newcastle refer to themselves as "Novocastrians".

References

- ^ a b "Aboriginal Archaeological Report for former Palais site released". Coal River Working Party. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ^ a b "History". Hunter Living Histories. 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e "Discovery and founding of Newcastle". Newcastle City Council. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Newcastle". Sydney Morning Herald. 2004-02-08. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ a b "Old Great North Road more information". Australian Government. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ "Hunter History Highlights". Hunter Valley Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ^ "La Divina Commedia Di Mulubinba: The Art and Science of Time Travel" (PDF). State Library of NSW. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "Sydney Gazette" (PDF). 1804-03-25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Ida Lee. "The Logbooks of the Lady Nelson by Ida Lee". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ An Early Link with the New South Wales Railways Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin October 1954 pages 126-128

- ^ "The Namoi – Paddle steamer (P.S.)". Pittwater Online News. 2020-06-23. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ "Ships And Shores And Trading Ports". NSW Maritime. Archived from the original on 2008-07-20. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "The Sixty Miler". Australian National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 2007-09-07. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ "Newcastle Shelled by a Japanese Submarine on 8 June 1942". Battle for Australia Association Fort Scratchley 1942. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ "A distant dream becomes rail reality". The Age. 2004-01-10. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ W. J. Goold. "The early days of Mayfield". San Clemente High School. Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ "Steel City without the Big Australian". ABC News. 1999-09-29. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ Wikinews, Worst Storm in 30 years, Wikinews, 9 June 2007

- ^ "Body find brings toll to nine". Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Australian Associated Press (2007-06-09). "Natural disaster zones declared". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ "Newcastle Fatality – Ferry Collides With Steamer". The Canberra Times. 1934-08-11. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ "Ferry at Fault". The Canberra Times. 1934-08-25. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ a b "Fly-Past To Honour Sabre Pilot". Department of Defence. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Minister For Ports And Waterways; Minister For Regulatory Reform; Minister For Small Business (6 August 2008). "New Trade Record for Newcastle Port" (PDF). Media releases. Newcastle Port Corporation. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite web}}:|author3=has generic name (help) - ^ "Green groups block world's largest coal export terminal". Mineweb. Reuters. 2008-07-14. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ "The People's Blockade of the World's Biggest Coal Port". Rising Tide Australia. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ "Hunter Region Funding Cutbacks". Parliament of New South Wales. 1997-04-15. Retrieved 2008-07-10. (see Mr PRICE (Waratah) [4.13 p.m.])

- ^ "Defence forum to focus on Newcastle ship building". ABC News. 2008-04-18. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ Elkin, A.P., The Diocese of Newcastle: a history of the Diocese of Newcastle, Australian Medical Publishing Co: Glebe, NSW, 1955. (Privately published)

- Docherty, James Cairns, Newcastle – The Making of an Australian City, Sydney, 1983, ISBN 0-86806-034-8

- Susan Marsden, Coals to Newcastle: a History of Coal Loading at the Port of Newcastle New South Wales 1977–1997 2002

- Marsden, Susan, Newcastle: a Brief History Newcastle, 2004 ISBN 0-949579-17-3

- Marsden, Susan, 'Waterfront alive: life on the waterfront', in C Hunter, ed, River Change: six new histories of the Hunter, Newcastle, 1998 ISBN 0-909115-70-2

- Greater Newcastle City Council, Newcastle 150 Years, 1947.

- Thorne, Ross, Picture Palace Architecture in Australia, Melbourne, Victoria, 1976 (P/B), ISBN 0-7251-0226-8

- Turner, Dr. John W., Manufacturing in Newcastle, Newcastle, 1980, ISBN 0-9599385-7-5

- Morrison James, Ron, Newcastle – Times Past, Newcastle, 2005 (P/B), ISBN 0-9757693-0-8

External links

- Newcastle City Council Local History Link

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090915195229/http://newcbd.gpt.com.au/Content/?ids=Place%2FHistory Newcastle City Centre History Section]