History of the ancient Levant

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

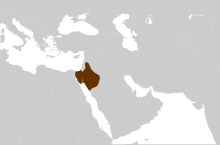

The Levant is the area in Southwest Asia, south of the Taurus Mountains, bounded by the Mediterranean Sea in the west, the Arabian Desert in the south, and Mesopotamia in the east. It stretches 400 mi (640 km) north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai desert, and 70–100 mi (110–160 km) east to west between the sea and the Arabian desert.[1] The term is also sometimes used to refer to modern events or states in the region immediately bordering the eastern Mediterranean Sea: the Hatay Province of Turkey, Cyprus, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan.

The term normally does not include Anatolia (although at times Cilicia may be included), the Caucasus Mountains, Mesopotamia or any part of the Arabian Peninsula proper. The Sinai Peninsula is sometimes included, though it is more considered an intermediate, peripheral or marginal area forming a land bridge between the Levant and northern Egypt.

| History of the Levant |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Ancient history |

| Classical antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

Stone Age

Paleolithic

Anatomically modern Homo sapiens are demonstrated at the area of Mount Carmel[2] in modern-day Israel during the Middle Paleolithic dating from c. 90,000 BC. These migrants out of Africa seem to have been unsuccessful,[3] and by c. 60,000 BC in the Levant, Neanderthal groups seem to have benefited from the worsening climate and replaced Homo sapiens, who were possibly confined once more to Africa.[4][3]

A second move out of Africa is demonstrated by the Boker Tachtit Upper Paleolithic culture, from 52,000 to 50,000 BC, with humans at Ksar Akil XXV level being modern humans.[5] This culture bears close resemblance to the Badoshan Aurignacian culture of Iran, and the later Sebilian I Egyptian culture of c. 50,000 BC. Stephen Oppenheimer[6] suggests that this reflects a movement of modern human (possibly Caucasian) groups back into North Africa, at this time.

It would appear this sets the date by which Homo sapiens Upper Paleolithic cultures begin replacing Neanderthal Levalo-Mousterian, and by c. 40,000 BC the region was occupied by the Levanto-Aurignacian Ahmarian culture, lasting from 39,000 to 24,000 BC.[7] This culture was quite successful spreading as the Antelian culture (late Aurignacian), as far as Southern Anatolia, with the Atlitan culture.

Epi-Palaeolithic

After the Late Glacial Maxima, a new Epipaleolithic culture appears. The appearance of the Kebaran culture, of microlithic type implies a significant rupture in the cultural continuity of Levantine Upper Paleolithic. The Kebaran culture, with its use of microliths, is associated with the use of the bow and arrow and the domestication of the dog.[8] Extending from 18,000 to 10,500 BC, the Kebaran culture[9] shows clear connections to the earlier Microlithic cultures using the bow and arrow, and using grinding stones to harvest wild grains, that developed from the c. 24,000 – c. 17,000 BC Halfan culture of Egypt, that came from the still earlier Aterian tradition of the Sahara. Some linguists see this as the earliest arrival of Nostratic languages in the Middle East.

Kebaran culture was quite successful, and was ancestral to the later Natufian culture (12,500–9,500 BC), which extended throughout the whole of the Levantine region. These people pioneered the first sedentary settlements, and may have supported themselves from fishing and the harvest of wild grains plentiful in the region at that time. As of July 2018,[update] the oldest remains of bread were discovered c. 12,400 BC at the archaeological site of Shubayqa 1, once home of the Natufian hunter-gatherers, roughly 4,000 years before the advent of agriculture.[10]

Natufian culture also demonstrates the earliest domestication of the dog, and the assistance of this animal in hunting and guarding human settlements may have contributed to the successful spread of this culture. In the northern Syrian, eastern Anatolian region of the Levant, Natufian culture at Cayonu and Mureybet developed the first fully agricultural culture with the addition of wild grains, later being supplemented with domesticated sheep and goats, which were probably domesticated first by the Zarzian culture of Northern Iraq and Iran (which like the Natufian culture may have also developed from Kebaran).

Neolithic and Chalcolithic

By 8500–7500 BC, the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) culture developed out of the earlier local tradition of Natufian, dwelling in round houses, and building the first defensive site at Tell es-Sultan (ancient Jericho) (guarding a valuable fresh water spring). This was replaced in 7500 BC by Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), dwelling in square houses, coming from Northern Syria and the Euphrates bend.

During the period of 8500–7500 BC, another hunter-gatherer group, showing clear affinities with the cultures of Egypt (particularly the Outacha retouch technique for working stone) was in Sinai. This Harifian culture[11] may have adopted the use of pottery from the Isnan culture and Helwan culture of Egypt (which lasted from 9000 to 4500 BC), and subsequently fused with elements from the PPNB culture during the climatic crisis of 6000 BC to form what Juris Zarins calls the Syro-Arabian pastoral technocomplex,[12] which saw the spread of the first Nomadic pastoralists in the Ancient Near East. These extended southwards along the Red Sea coast and penetrating the Arabian bifacial cultures, which became progressively more Neolithic and pastoral, and extending north and eastwards, to lay the foundations for the tent-dwelling Martu and Akkadian peoples of Mesopotamia.

In the Amuq valley of Syria, PPNB culture seems to have survived, influencing further cultural developments further south. Nomadic elements fused with PPNB to form the Minhata Culture and Yarmukian Culture, which were to spread southwards, beginning the development of the classic mixed farming Mediterranean culture, and from 5600 BC were associated with the Ghassulian culture of the region, the first Chalcolithic culture of the Levant. This period[which?] also witnessed the development of megalithic structures, which continued into the Bronze Age.[13][dubious ]

Kish civilization

The Kish civilization or Kish tradition is a concept created by Ignace Gelb and discarded by more recent scholarship,[14] which Gelb placed in what he called the early East Semitic era in Mesopotamia and the Levant, starting in the early 4th millennium BC. The tradition encompasses the sites of Ebla and Mari in the Levant, Nagar in the north,[15] and the proto-Akkadian sites of Abu Salabikh and Kish in central Mesopotamia, which constituted the Uri region as it was known to the Sumerians.[16][17][better source needed] The Kish civilisation is considered to end with the rise of the Akkadian empire in the 24th century BC.[18]

Bronze Age

Syria: between Mesopotamia and Anatolia

Some recent scholars dealing with the Syrian part of the Levant during the Bronze Age are using Syria-specific subdivision: "Early/Proto Syrian" for the Early Bronze Age (c. 3300-2000 BC); "Old Syrian" for the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000-1550 BC); and "Middle Syrian" for the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550-1200 BC). "Neo-Syrian" corresponds to the Early Iron Age.[19]

The Early Syrian period was dominated by the East Semitic-speaking Eblaite first kingdom (3000 BC - 2300 BC), Kingdom of Nagar (2600 BC - 2300 BC) and the Mariote second kingdom (2500 BC - 2290 BC). The Akkadian Empire conquered large areas of the Levant, but collapsed due to the 4.2 kiloyear event circa 2200 BC. This event prompted movement of populations from Upper Mesopotamia to the northern Levant. The Akkadians were followed by a long period of Amorite dominance in Syria ca. 2200-1600 BC. The Amorites established powerful kingdoms and city-states throughout the Fertile Crescent, including Yamhad, Eblaite third kingdom, Alalakh, and Qatna in the Levant, and Babylon, Mari, Apum, Kurda, Ekallatum, Andarig and Shamshi-Adad I's kingdom in Mesopotamia. After the collapse of the Akkadian empire, Hurrians settlements commenced westwards, and by the 17th century BC the Hurrians made up a significant portion of the population in Aleppo, Alalakh and Ugarit. Also following the Akkadians was the extension of Khirbet Kerak Ware culture, showing affinities with the Caucasus, and possibly linked to the later appearance of the Hurrians.

Around the 16th and 15th centuries BC most of the older centers had been overrun. In northern Mesopotamia, the era ended with the defeat and expulsion of the Amorites and Amorite-dominated Babylonians from Assyria by Puzur-Sin and king Adasi between 1740 and 1735 BC, and in the far south, by the rise of the native Sealand Dynasty c. 1730 BC.[20] Babylon was taken over by the Kassites in 1595 BC. Mitanni emerged in northern Syria as a powerful player in the 16th century, and were under constant threat from their surrounding neighbors, Hittites and Assyria, prompting them to forge close ties with Egypt. Mitanni was predominantly made up of Hurrian, Akkadian and Amorite speaking populations.

After the fall of Mitanni in the 14th century, Syria came under the domination of the Hittites and the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050). The Amorites were displaced or absorbed by a semi-nomadic West Semitic-speaking peoples known collectively as the Ahlamu, during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Arameans rose to be the prominent group amongst the Ahlamu, and from c. 1200 BC on, the Amorites disappeared from the pages of history.

Egypt: Hyksos; expansion

In the mid-17th century BC, the Hyksos overran Egypt, either by coup or an invasion, and founded the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt in Avaris. The origins of the Hyksos are unknown, but they were potentially linked to the Amorites of Syria. The Hyksos were later expelled, leaving the empire of the New Kingdom to develop in their wake.

Around the beginning of the New Kingdom period, Egypt exerted rule over much of the Levant. From 1550 until 1100, much of the Levant was conquered by Egypt, which in the latter half of this period contested Syria with the Hittite Empire. Rule remained strong during the Eighteenth Dynasty, but Egypt's rule became precarious during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties. Ramses II was able to maintain control over it in the stalemated battle against the Hittites at Kadesh in 1275 BC, but soon thereafter, the Hittites successfully took over the northern Levant (Syria and Amurru). Ramses II, obsessed with his own building projects while neglecting Asiatic contacts, allowed control over the region to continue dwindling. During the reign of his successor Merneptah, the Merneptah Stele was issued which claimed to have destroyed various sites in the southern Levant, including a people named as "Israel". A newly discovered massive layer of fiery destruction confirms Merneptah's boast about his Canaanite campaign.[21]

Over the course of the reign of Ramses VI (C.1125 BC), Egyptian control over the southern Levant completely collapsed in the wake of the invasion of the Sea Peoples, more specifically, the Philistines who settled into the southwestern Coastal Plain.[22]

Collapse

At the end of the 13th century BC, all of these powers suddenly collapsed. Cities all around the eastern Mediterranean were sacked within a span of a few decades by assorted raiders known as the Sea Peoples, a confederation of both local and foreign warriors and tribes that settled in the Levant after the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Hittite empire was destroyed and its capital was razed to the ground. Egypt repelled its attackers with only a major effort, and over the next century shrank to its territorial core, its central authority permanently weakened. Multiple cities like Ugarit, Alalakh and other Canaanite cities were destroyed by the Sea Peoples.[clarification needed]

Iron Age

The destruction at the end of the Bronze Age left a number of tiny kingdoms and city-states behind. Semitic, Hittite and Luwian-speaking centres were established in northern Syria, the Syro-Hittite states, after the main Hittite state fell in 1180 BC, along with some Phoenician ports in Canaan that escaped destruction and developed into great commercial powers. In the 12th century BC, most of the interior, as well as Babylonia and Upper Mesopotamia, was overrun by Arameans, Chaldeans and Suteans from the west forming kingdoms all along central and northern Syria reaching Upper Mesopotamia, while the shoreline around today's Gaza Strip was settled by Philistines.

The Israelites emerged as a rural culture, mainly in the Canaanite hill-country and the Eastern Galilee, quickly spreading throughout the region and forming an alliance in the struggle for the land against the Philistines to the west, Moab and Ammon to the east, and Edom to the south.

A mysterious group (or groups) of people called the 'Aribi', possibly Arabs, appeared in historical record c. 8th century BC inhabiting inner Syria, Jordan and northern Arabia, and formed kingdoms and tribal confederations, most notably Qedarites in northern Arabia and southern Syria, and the Nabatu, potential precursors of the Nabataeans, in Palmyra, Damascus and al-Leja in south and central Syria.[23][24][clarification needed][better source needed]

In this period a number of technological innovations spread, most notably iron working and the Phoenician alphabet, the latter developed by the Phoenicians or the Canaanites around the 11th century BC from the Old Canaanite script.[25]

In 612 BC Cilicia, ruled by the Syennesis dynasty, became an independent kingdom and managed to remain so until 549 BC. It had previously been autonomous under the Assyrians, and would remain so afterwards under the Achaemenid Empire.

During the 9th century BC, the Assyrians began to reassert themselves against the incursions of the Aramaeans, and over the next few centuries developed into a powerful and well-organised empire. Their armies were among the first to employ cavalry, which took the place of chariots, and had a reputation for both prowess and brutality. They launched campaigns against the Arameans and Sutean tribes living in central Syria and Upper Mesopotamia, expelling them and destroying their city-states and confederations. At their height, the Assyrians dominated all of the Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. However, the empire began to collapse toward the end of the 7th century BC, and was obliterated by an alliance between a resurgent New Kingdom of Babylonia and the Iranian Medes.

After the Battle of Carchemish (c. 605 BC), Nebuchadnezzar II besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple (597 BC), starting the period of the Babylonian captivity, which lasted about half a century. The subsequent balance of power was short-lived, though. In the 550s BC the Persians revolted against the Medes and gained control of their empire, and over the next few decades annexed to it the realms of Lydia in Anatolia, Damascus, Babylonia, and Egypt, as well as consolidating their control over the Iranian plateau nearly as far as India. This vast kingdom was divided up into various satrapies and governed roughly according to the Assyrian model, but with a far lighter hand. Around this time Zoroastrianism became the predominant religion in Persia.

Classical Age

Persia controlled the Levant, but by the 4th century BC Persia had fallen into decline. The Phoenicians occasionally rebelled against the Persians who taxed them heavily, while the Jews were granted return from the exile by Cyrus the Great. The campaigns of Xenophon in 401-399 BC illustrated how very vulnerable Persia had become to armies organized along Greek lines. Such an army under the Macedonian King Alexander the Great conquered the Levant (333-332 BC).

Alexander did not live long enough to consolidate his realm; after his death in 323 BC the greater share of the east eventually went to the descendants of Seleucus I Nicator. Hellenistic culture developed as a fusion of ancient Greek culture and the local cultures of the region; the period saw great innovations in mathematics, science, philosophy and the like; in addition Seleucids founded multiple cities throughout the region and sponsored Greek settlement from Euboea, Crete and Aetolia, in the region.[26] Later on in history, the Seleucid king adopted the title "King of Syria".

The Seleucids (312 to 63 BC) adopted a pro-western stance that alienated both the powerful eastern satraps and many Greeks who had migrated to the east. During the 2nd century BC, the Seleucid Empire went into decline and began to break apart. By the 1st century BC, localized kingdoms were established away from Seleucid control. In northern Levant, Osroene and Commagene were established as northern buffer states in the mid-2nd century BC. In the central and southern Levant, the Nabataean Kingdom was established in the 3rd century BC, the Maccabean Revolt brought independence to Judaea and surrounding regions under the Hasmonean dynasty around 140 BC, and the Kingdom of Chalcis in Iturea broke away in 80 BC. This rendered the Seleucids a weak, vulnerable state limited to parts of Syria and Lebanon.

The first to second centuries also saw the emergence of a plethora of religions and philosophical schools. Philosophical schools emerged under famous philosophers at the time, most notably Neoplatonism under Iamblichus and Porphyry, Neopythagorianism under Apollonius of Tyana and Numenius of Apamea, and Hellenic Judaism under Philo of Alexandria. Christianity emerged as a sect of Judaism and finally as an independent religion by the mid second century. Gnosticism also took hold in the region.

The Romans gained permanent foothold in the region by 64 BC, and by the 1st century CE came to include the remaining vassal states in the Roman Empire. A Persian dynasty, the Sassanids (224-651), periodically clashed with Rome, and later with the Byzantine Empire. In 391 the Byzantine era began with the permanent division of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western halves. Byzantine control over many parts of the Levant lasted until 636, when Arab armies conquered the area and it became a part of the Rashidun Caliphate.

The Byzantines reached a low point under Phocas (Byzantine Emperor from 602 to 610), with the Sassanids occupying the whole of the eastern Mediterranean. In 610, though, Heraclius took the throne in Constantinople and began a successful counter-attack, expelling the Persians and invading Media and Assyria. Unable to stop his advance, the Sassanian king Khosrau II was assassinated (628) and the Sassanid empire fell into anarchy. Weakened by their quarrels, neither the Byzantines nor the Sassanids could deal with the onslaught of the Arabs, newly unified under the banners of Islam and keen to expand their area of control. By 650 Arab forces had conquered all of Persia, Syria, and Upper Egypt[dubious ].[citation needed]

See also

- Names of the Levant

- History of the Middle East

- List of archaeological periods (Levant)

- Ancient Near East

- Levantine archaeology

- Near Eastern bioarchaeology

- History of the ancient Levant

- History of Cyprus

- History of Palestine – same as "History of Israel", with a non-Jewish focus

- History of Israel i.e. of the "land of Israel" – same as "History of Palestine", with a Jewish focus

- History of Jordan

- History of the Sinai Peninsula

- Prehistory of the Levant

- History of Islam

References

Notes

- ^ A History of Ancient Israel and Judah by Miller, James Maxwell, and Hayes, John Haralson (Westminster John Knox, 1986) ISBN 0-664-21262-X. p.36

- ^ "Sites of Human Evolution at Mount Carmel: The Nahal Me'arot / Wadi el-Mughara Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2019-07-17. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ^ a b Beyin, Amanuel (2011). "Upper Pleistocene Human Dispersals out of Africa: A Review of the Current State of the Debate". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011: 615094. doi:10.4061/2011/615094. ISSN 2090-052X. PMC 3119552. PMID 21716744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Amud". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Marks, Anthony (1983)"Prehistory and Paleoenvironments in the Central Negev, Israel" (Institute for the Study of Earth and Man, Dallas)

- ^ Oppemheiomer, Stephen (2004), "Out of Eden", (Constable and Robinson)

- ^ Gladfelter, Bruce G. (1997) "The Ahmarian tradition of the Levantine Upper Paleolithic: the environment of the archaeology" (Vol 12, 4 Geoarchaeology)

- ^ Dayan, Tamar (1994), "Early Domesticated Dogs of the Near East" (Journal of Archaeological Science Volume 21, Issue 5, September 1994, Pages 633–640)

- ^ Ronen, Avram, "Climate, sea level, and culture in the Eastern Mediterranean 20 ky to the present" in Valentina Yanko-Hombach, Allan S. Gilbert, Nicolae Panin and Pavel M. Dolukhanov (2007), The Black Sea Flood Question: Changes in Coastline, Climate, and Human Settlement (Springer)

- ^ Mejia, Paula (16 July 2018). "Found: 14,400-Year-Old Flatbread Remains That Predate Agriculture". Gastro Obscura. Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Belfer-Cohen, Anna and Bar-Yosef, Ofer "Early Sedentism in the Near East: A Bumpy Ride to Village Life" (Fundamental Issues in Archaeology, 2002, Part II, 19–38)

- ^ Zarins, Yuris "Early Pastoral Nomadiism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia" (# Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research No. 280, November, 1990)

- ^ Scheltema, H.G. (2008). Megalithic Jordan: An Introduction and Field Guide. Amman, Jordan: The American Center of Oriental Research. ISBN 978-9957-8543-3-1 No Google Books access.

- ^ Sommerfeld, Walter (2021). Vita, Juan-Pablo (ed.). The "Kish Civilization". Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1 The Near and Middle East. Vol. 1. BRILL. pp. 545–547. ISBN 9789004445215. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ristvet, Lauren (2014). Ritual, Performance, and Politics in the Ancient Near East. p. 217. ISBN 9781107065215.

- ^ Van De Mieroop, Marc (2002). Erica Ehrenberg (ed.). In Search of Prestige: Foreign Contacts and the Rise of an Elite in Early Dynastic Babylonia. p. 125-137 [133]. ISBN 9781575060552. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wyatt, Lucy (2010). Approaching Chaos: Could an Ancient Archetype Save 21st Century Civilization?. O Books. p. 120. ISBN 9781846942556. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Hasselbach (2005). p. 4.

- ^ Hansen, M. H. (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation, Volume 21. p. 57. ISBN 9788778761774. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Amorites". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 876.

- ^ Bohstrom, Philippe (2017). "First Discovery of Bodies in Biblical Gezer, From Fiery Destruction 3,200 Years Ago".

- ^ Dever, William G. Beyond the Texts, Society of Biblical Literature Press, 2017, pp. 89-93

- ^ Paton, Lewis Bayles (1901), The Early History of Syria and Palestine, C. Scribner's Sons, p. 269, ISBN 9780554479590

- ^ Guzzo et al., 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Cross, Frank Moore (1991). Senner, Wayne M. (ed.). The Invention and Development of the Alphabet. Bison books. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 77–90 [81]. ISBN 978-0-8032-9167-6. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Chaniotis, 2006, p.85

General references

- Philip Mansel, Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean, London, John Murray, 11 November 2010, hardback, 480 pages, ISBN 978-0-7195-6707-0, New Haven, Yale University Press, 24 May 2011, hardback, 470 pages, ISBN 978-0-300-17264-5