Sense of smell

Olfaction (also known as olfactics; adjectival form: "olfactory") is the sense of smell. This sense is mediated by specialized sensory cells of the nasal cavity of vertebrates, and, by analogy, sensory cells of the antennae of invertebrates. Many vertebrates, including most mammals and reptiles, have two distinct olfactory systems—the main olfactory system, and the accessory olfactory system (used mainly to detect pheromones). For air-breathing animals, the main olfactory system detects volatile chemicals, and the accessory olfactory system detects fluid-phase chemicals.[1] Olfaction, along with taste, is a form of chemoreception. The chemicals themselves that activate the olfactory system, in general at very low concentrations, are called odorants. Although taste and smell are separate sensory systems in land animals, water-dwelling organisms often have one chemical sense.[2]

Volatile small molecule odorants, non-volatile proteins, and non-volatile hydrocarbons may all produce olfactory sensations. Some animal species are able to smell carbon dioxide in minute concentrations. Taste sensations are caused by small organic molecules and proteins.[3]

History

As the Epicurean and atomistic Roman philosopher Lucretius (1st Century BCE) speculated, different odors are attributed to different shapes and sizes of odor molecules that stimulate the olfactory organ. A modern demonstration of that theory was the cloning of olfactory receptor proteins by Linda B. Buck and Richard Axel (who were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2004), and subsequent pairing of odor molecules to specific receptor proteins. Each odor receptor molecule recognizes only a particular molecular feature or class of odor molecules. Mammals have about a thousand genes that code for odor reception.[4] Of the genes that code for odor receptors, only a portion are functional. Humans have far fewer active odor receptor genes than other primates and other mammals.[5]

In mammals, each olfactory receptor neuron expresses only one functional odor receptor.[6] Odor receptor nerve cells function like a key-lock system: If the airborne molecules of a certain chemical can fit into the lock, the nerve cell will respond. There are, at present, a number of competing theories regarding the mechanism of odor coding and perception. According to the shape theory, each receptor detects a feature of the odor molecule. Weak-shape theory, known as odotope theory, suggests that different receptors detect only small pieces of molecules, and these minimal inputs are combined to form a larger olfactory perception (similar to the way visual perception is built up of smaller, information-poor sensations, combined and refined to create a detailed overall perception).[7] An alternative theory, the vibration theory proposed by Luca Turin,[8][9] posits that odor receptors detect the frequencies of vibrations of odor molecules in the infrared range by electron tunnelling. However, the behavioral predictions of this theory have been called into question.[10] As of yet, there is no theory that explains olfactory perception completely.

Main olfactory system

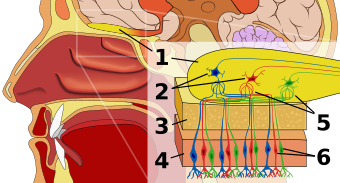

In vertebrates smells are sensed by olfactory sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium. The proportion of olfactory epithelium compared to respiratory epithelium (not innervated) gives an indication of the animal's olfactory sensitivity. Humans have about 10 cm2 (1.6 sq in) of olfactory epithelium, whereas some dogs have 170 cm2 (26 sq in). A dog's olfactory epithelium is also considerably more densely innervated, with a hundred times more receptors per square centimetre.[11]

Molecules of odorants passing through the superior nasal concha of the nasal passages dissolve in the mucus lining the superior portion of the cavity and are detected by olfactory receptors on the dendrites of the olfactory sensory neurons. This may occur by diffusion or by the binding of the odorant to odorant binding proteins. The mucus overlying the epithelium contains mucopolysaccharides, salts, enzymes, and antibodies (these are highly important, as the olfactory neurons provide a direct passage for infection to pass to the brain).

In insects smells are sensed by olfactory sensory neurons in the chemosensory sensilla, which are present in insect antenna, palps and tarsa, but also on other parts of the insect body. Odorants penetrate into the cuticle pores of chemosensory sensilla and get in contact with insect Odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) or Chemosensory proteins (CSPs), before activating the sensory neurons.

Receptor neuron

The binding of the ligand (odor molecule or odorant) to the receptor leads to an action potential in the receptor neuron, via a second messenger pathway, depending on the organism. In mammals, the odorants stimulate adenylate cyclase to synthesize CAMP via a G protein called Golf. CAMP, which is the second messenger here, opens a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel (CNG), producing an influx of cations (largely Ca2+ with some Na+) into the cell, slightly depolarising it. The Ca2+ in turn opens a Ca2+-activated chloride channel, leading to efflux of Cl-, further depolarising the cell and triggering an action potential. Ca2+ is then extruded through a sodium-calcium exchanger. A calcium-calmodulin complex also acts to inhibit the binding of CAMP to the CAMP-dependent channel, thus contributing to olfactory adaptation. This mechanism of transduction is somewhat unique, in that CAMP works by directly binding to the ion channel rather than through activation of protein kinase A. It is similar to the transduction mechanism for photoreceptors, in which the second messenger cGMP works by directly binding to ion channels, suggesting that maybe one of these receptors was evolutionarily adapted into the other. There are also considerable similarities in the immediate processing of stimuli by lateral inhibition. Averaged activity of the receptor neurons can be measured in several ways. In vertebrates, responses to an odor can be measured by an electro-olfactogram or through calcium imaging of receptor neuron terminals in the olfactory bulb. In insects, one can perform electroantenogram or also calcium imaging within the olfactory bulb.

Olfactory bulb projections

Olfactory sensory neurons project axons to the brain within the olfactory nerve, (cranial nerve I). These nerve fibers, lacking myelin sheaths, pass to the olfactory bulb of the brain through perforations in the cribriform plate, which in turn projects olfactory information to the olfactory cortex and other areas.[12] The axons from the olfactory receptors converge in the outer layer of the olfactory bulb within small (~50 micrometers in diameter) structures called glomeruli. Mitral cells, located in the inner layer of the olfactory bulb, form synapses with the axons of the sensory neurons within glomeruli and send the information about the odor to other parts of the olfactory system, where multiple signals may be processed to form a synthesized olfactory perception. A large degree of convergence occurs, with twenty-five thousand axons synapsing on twenty-five or so mitral cells, and with each of these mitral cells projecting to multiple glomeruli. Mitral cells also project to periglomerular cells and granular cells that inhibit the mitral cells surrounding it (lateral inhibition). Granular cells also mediate inhibition and excitation of mitral cells through pathways from centrifugal fibers and the anterior olfactory nuclei.

The mitral cells leave the olfactory bulb in the lateral olfactory tract, which synapses on five major regions of the cerebrum: the anterior olfactory nucleus, the olfactory tubercle, the amygdala, the piriform cortex, and the entorhinal cortex. The anterior olfactory nucleus projects, via the anterior commissure, to the contralateral olfactory bulb, inhibiting it. The piriform cortex has two major divisions with anatomically distinct organizations and functions. The anterior pririform cortex (APC) is better assoicated with determining the chemical structure of the odorant molecules and whereas the posterior pririform cortex (PPC) is best known for its strong role in categorizing odors and assessing similarities between odors (eg minty, woody, citrus are odors which can be distinguished via the PPC despite being highly-variant chemicals and in a concentration-independent manner).[13] The piriform cortex projects to the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus, which then projects to the orbitofrontal cortex. The orbitofrontal cortex mediates conscious perception of the odor. The 3-layered piriform cortex projects to a number of thalamic and hypothalamic nuclei, the hippocampus and amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex but its function is largely unknown. The entorhinal cortex projects to the amygdala and is involved in emotional and autonomic responses to odor. It also projects to the hippocampus and is involved in motivation and memory. Odor information is stored in long-term memory and has strong connections to emotional memory. This is possibly due to the olfactory system's close anatomical ties to the limbic system and hippocampus, areas of the brain that have long been known to be involved in emotion and place memory, respectively.

Since any one receptor is responsive to various odorants, and there is a great deal of convergence at the level of the olfactory bulb, it seems strange that human beings are able to distinguish so many different odors. It seems that there must be a highly-complex form of processing occurring; however, as it can be shown that, while many neurons in the olfactory bulb (and even the pyriform cortex and amygdala) are responsive to many different odors, half the neurons in the orbitofrontal cortex are responsive to only one odor, and the rest to only a few. It has been shown through microelectrode studies that each individual odor gives a particular specific spatial map of excitation in the olfactory bulb. It is possible that, through spatial encoding, the brain is able to distinguish specific odors. However, temporal coding must be taken into account. Over time, the spatial maps change, even for one particular odor, and the brain must be able to process these details as well.

Inputs from the two nostrils have separate inputs to the brain with the result that it is possible for humans to experience perceptual rivalry in the olfactory sense akin to that of binocular rivalry when there are two different inputs into the two nostrils.[14]

In insects smells are sensed by sensilla located on the antenna and maxillary palp and first processed by the antennal lobe (analogous to the olfactory bulb), and next by the mushroom bodies and lateral horn.

Accessory olfactory system

Many animals, including most mammals and reptiles, but not humans, have two distinct and segregated olfactory systems: a main olfactory system, which detects volatile stimuli, and an accessory olfactory system, which detects fluid-phase stimuli. Behavioral evidence suggests that these fluid-phase stimuli often function as pheromones, although pheromones can also be detected by the main olfactory system. In the accessory olfactory system, stimuli are detected by the vomeronasal organ, located in the vomer, between the nose and the mouth. Snakes use it to smell prey, sticking their tongue out and touching it to the organ. Some mammals make a facial expression called flehmen to direct stimuli to this organ.

The sensory receptors of the accessory olfactory system are located in the vomeronasal organ. As in the main olfactory system, the axons of these sensory neurons project from the vomeronasal organ to the accessory olfactory bulb, which in the mouse is located on the dorsal-posterior portion of the main olfactory bulb. Unlike in the main olfactory system, the axons that leave the accessory olfactory bulb do not project to the brain's cortex but rather to targets in the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and from there to the hypothalamus, where they may influence aggressive and mating behavior.

Human olfactory system

In women, the sense of olfaction is strongest around the time of ovulation, significantly stronger than during other phases of the menstrual cycle and also stronger than the sense in males.[15]

The MHC genes (known as HLA in humans) are a group of genes present in many animals and important for the immune system; in general, offspring from parents with differing MHC genes have a stronger immune system. Fish, mice and female humans are able to smell some aspect of the MHC genes of potential sex partners and prefer partners with MHC genes different from their own.[16][17]

Humans can detect individuals that are blood-related kin (mothers and children but not husbands and wives) from olfaction.[18] Mothers can identify by body odor their biological children but not their stepchildren. Preadolescent children can olfactorily detect their full siblings but not half-siblings or step siblings and this might explain incest avoidance and the Westermarck effect.[19] Functional imaging shows that this olfactory kinship detection process involves the frontal-temporal junction, the insula, and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex but not the primary or secondary olfactory cortices, or the related piriform cortex or orbitofrontal cortex.[20]

Olfactory coding and perception

How olfactory information is coded in the brain to allow for proper perception is still being researched and the process is not completely understood. However, what is known is that the chemical nature of the odorant is particularly important, as there may be a chemotopic map in the brain; this map would show specific activation patterns for specific odorants. When an odorant is detected by receptors, the receptors in a sense break the odorant down and then the brain puts the odorant back together for identification and perception.[21] The odorant binds to receptors which only recognize a specific functional group, or feature, of the odorant, which is why the chemical nature of the odorant is important.[22]

After binding the odorant, the receptor is activated and will send a signal to the glomeruli.[22] Each glomerulus receives signals from multiple receptors that detect similar odorant features. Because multiple receptor types are activated due to the different chemical features of the odorant, multiple glomeruli will be activated as well. All of the signals from the glomeruli will then be sent to the brain, where the combination of glomeruli activation will encode the different chemical features of the odorant. The brain will then essentially put the pieces of the activation pattern back together in order to identify and perceive the odorant.[22]

Odorants that are similar in structure activate similar patterns of glomeruli, which lead to a similar perception in the brain.[22][23] Data from animal models, suggests that the brain may have a chemotopic map. A chemotopic map is an area in the brain, to be specific the olfactory bulb, in which glomeruli project their signals onto the brain in a specific pattern. The idea of the chemotopic map has been supported by the observation that chemicals containing similar functional groups have similar responses with overlapped areas in the brain. This is important because it allows the possibility to predict the neural activation pattern from an odorant and vice versa.[22]

Interactions of olfaction with other senses

Olfaction and taste

Olfaction, taste and trigeminal receptors (also called Chemesthesis) together contribute to flavor. The human tongue can distinguish only among five distinct qualities of taste, while the nose can distinguish among hundreds of substances, even in minute quantities. It is during exhalation that the olfaction contribution to flavor occurs, in contrast to that of proper smell, which occurs during the inhalation phase[24]

Olfaction and audition

Olfaction and sound information has been shown to converge in the olfactory tubercles of rodents.[25] This neural convergence is proposed to give rise to a percept termed smound.[26] Whereas a flavor results from interactions between smell and taste, a smound may result from interactions between smell and sound.

Disorders of olfaction

The following are disorders of olfaction:[27]

- Anosmia – inability to smell

- Cacosmia – things smell like feces[28]

- Dysosmia – things smell different than they should

- Hyperosmia – an abnormally acute sense of smell.

- Hyposmia – decreased ability to smell

- Olfactory Reference Syndrome – psychological disorder which causes the patient to imagine he or she has strong body odor

- Parosmia – things smell worse than they should

- Phantosmia – "hallucinated smell," often unpleasant in nature

Quantifying olfaction in industry

Scientists have devised methods for quantifying the intensity of odors, in particular for the purpose of analyzing unpleasant or objectionable odors released by an industrial source into a community. Since the 1800s, industrial countries have encountered incidents where proximity of an industrial source or landfill produced adverse reactions to nearby residents regarding airborne odor. The basic theory of odor analysis is to measure what extent of dilution with "pure" air is required before the sample in question is rendered indistinguishable from the "pure" or reference standard. Since each person perceives odor differently, an "odor panel" composed of several different people is assembled, each sniffing the same sample of diluted specimen air. A field olfactometer can be utilized to determine the magnitude of an odor.

Many air management districts in the USA have numerical standards of acceptability for the intensity of odor that is allowed to cross into a residential property. For example, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District has applied its standard in regulating numerous industries, landfills, and sewage treatment plants. Example applications this district has engaged are the San Mateo, California wastewater treatment plant; the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, California; and the IT Corporation waste ponds, Martinez, California.

Olfaction in plants and animals

The tendrils of plants are especially sensitive to airborne volatile organic compounds. Parasites such as dodder make use of this in locating their preferred hosts and locking on to them.[29] The emission of volatile compounds is detected when foliage is browsed by animals. Threatened plants are then able to take defensive chemical measures, such as moving tannin compounds to their foliage. (see Plant perception).

The importance and sensitivity of smell varies among different organisms; most mammals have a good sense of smell, whereas most birds do not, except the tubenoses (e.g., petrels and albatrosses), certain species of vultures and the kiwis. Among mammals, it is well-developed in the carnivores and ungulates, which must always be aware of each other, and in those that smell for their food, like moles. Having a strong sense of smell is referred to as macrosmatic.

Figures suggesting greater or lesser sensitivity in various species reflect experimental findings from the reactions of animals exposed to aromas in known extreme dilutions. These are, therefore, based on perceptions by these animals, rather than mere nasal function. That is, the brain's smell-recognizing centers must react to the stimulus detected, for the animal to show a response to the smell in question. It is estimated that dogs in general have an olfactory sense approximately a hundred thousand to a million times more acute than a human's. This does not mean they are overwhelmed by smells our noses can detect; rather, it means they can discern a molecular presence when it is in much greater dilution in the carrier, air. Scenthounds as a group can smell one- to ten-million times more acutely than a human, and Bloodhounds, which have the keenest sense of smell of any dogs [citation needed], have noses ten- to one-hundred-million times more sensitive than a human's. They were bred for the specific purpose of tracking humans, and can detect a scent trail a few days old. The second-most-sensitive nose is possessed by the Basset Hound, which was bred to track and hunt rabbits and other small animals.

Bears, such as the Silvertip Grizzly found in parts of North America, have a sense of smell seven times stronger than that of the bloodhound, essential for locating food underground. Using their elongated claws, bears dig deep trenches in search of burrowing animals and nests as well as roots, bulbs, and insects. Bears can detect the scent of food from up to 18 miles away; because of their immense size, they often scavenge new kills, driving away the predators (including packs of wolves and human hunters) in the process.

The sense of smell is less-developed in the catarrhine primates (Catarrhini), and nonexistent in cetaceans, which compensate with a well-developed sense of taste[citation needed]. In some prosimians, such as the Red-bellied Lemur, scent glands occur atop the head. In many species, olfaction is highly tuned to pheromones; a male silkworm moth, for example, can sense a single molecule of bombykol.

Fish too have a well-developed sense of smell, even though they inhabit an aquatic environment. Salmon utilize their sense of smell to identify and return to their home stream waters. Catfish use their sense of smell to identify other individual catfish and to maintain a social hierarchy. Many fishes use the sense of smell to identify mating partners or to alert to the presence of food.

Insects use primarily their antennae for olfaction. Sensory neurons in the antenna generate odor-specific electrical signals called spikes in response to odor. They process these signals from the sensory neurons in the antennal lobe followed by the mushroom bodies and lateral horn of the brain. The antennae have the sensory neurons in the sensilla and they have their axons terminating in the antennal lobes, where they synapse with other neurons there in semidelineated (with membrane boundaries) called glomeruli. These antennal lobes have two kinds of neurons, projection neurons (excitatory) and local neurons (inhibitory). The projection neurons send their axon terminals to mushroom body and lateral horn (both of which are part of the protocerebrum of the insects), and local neurons have no axons. Recordings from projection neurons show in some insects strong specialization and discrimination for the odors presented (especially for the projection neurons of the macroglomeruli, a specialized complex of glomeruli responsible for the pheromones detection). Processing beyond this level is not exactly known though some preliminary results are available.

See also

- Electronic nose

- Machine olfaction

- Nasal administration olfactory transfer

- Odor

- Olfactometer

- Olfactory fatigue

- Chemesthesis

- Major histocompatibility complex and sexual selection

References

- ^ Hussain A, Saraiva LR, Korsching SI (2009). "Positive Darwinian selection and the birth of an olfactory receptor clade in teleosts". PNAS. 106 (11): 4313–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803229106. PMC 2657432. PMID 19237578.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lera Boroditsky. (1999) "Taste, Smell, and Touch: Lecture Notes." pp. 1[1]

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2590501/

- ^ Buck L, Axel R (1991). "A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition". Cell. 65 (1): 175–87. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-X. PMID 1840504.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilad Y, Man O, Pääbo S, Lancet D (2003). "Human specific loss of olfactory receptor genes". PNAS. 100 (6): 3324–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0535697100. PMC 152291. PMID 12612342.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pinel, John P.J. (2006) Biopsychology. Pearson Education Inc. ISBN 0-205-42651-4 (page 178)

- ^ need citation!

- ^ Turin L (1996). "A spectroscopic mechanism for primary olfactory reception". Chemical senses. 21 (6): 773–91. doi:10.1093/chemse/21.6.773. PMID 8985605.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Turin L (2002). "A method for the calculation of odor character from molecular structure". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 216 (3): 367–85. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2504. PMID 12183125.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Keller A, Vosshall LB (2004). "A psychophysical test of the vibration theory of olfaction". Nature Neuroscience. 7 (4): 337–8. doi:10.1038/nn1215. PMID 15034588.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) See also the editorial on p. 315. - ^ Bear, Connors and Paradiso, Mark, Barry and Michael (2007). Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 265–275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morris, H., & Schaeffer, J. P. (1953). The Nervous system-The Brain or Encephalon. Human anatomy; a complete systematic treatise. (11th ed., pp.1218-1219). New York: Blakiston.

- ^ Nat Neurosci. 2009 Jul;12(7):813-4. A noseful of objects. Margot C.

- ^ Zhou W, Chen D (2009). "Binaral rivalry between the nostrils and in the cortex". Curr Biol. 19 (18): 1561–5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.052. PMC 2901510. PMID 19699095.

- ^ Navarrete-Palacios E, Hudson R, Reyes-Guerrero G, Guevara-Guzmán R (2003). "Lower olfactory threshold during the ovulatory phase of the menstrual cycle". Biological Psychology. 63 (3): 269–79. doi:10.1016/S0301-0511(03)00076-0. PMID 12853171.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boehm T, Zufall F (2006). "MHC peptides and the sensory evaluation of genotype". Trends in neurosciences. 29 (2): 100–7. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2005.11.006. PMID 16337283.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Santos PS, Schinemann JA, Gabardo J, Bicalho Mda G (2005). "New evidence that the MHC influences odor perception in humans: a study with 58 Southern Brazilian students". Hormones and behavior. 47 (4): 384–8. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.005. PMID 15777804.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Porter RH, Cernoch JM, Balogh RD (1985). "Odor signatures and kin recognition". Physiol Behav. 34 (3): 445–8. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(85)90210-0. PMID 4011726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weisfeld GE, Czilli T, Phillips KA, Gall JA, Lichtman CM (2003). "Possible olfaction-based mechanisms in human kin recognition and inbreeding avoidance". Journal of experimental child psychology. 85 (3): 279–95. doi:10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00061-4. PMID 12810039.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lundström JN, Boyle JA, Zatorre RJ, Jones-Gotman M (2009). "The neuronal substrates of human olfactory based kin recognition". Human Brain Mapping. 30 (8): 2571–80. doi:10.1002/hbm.20686. PMID 19067327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilson DA (2001). "Receptive fields in the rat piriform cortex". Chemical senses. 26 (5): 577–84. PMID 11418503.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Leon M., Johnson B.A. (2003). "Olfactory coding in the mammalian olfactory bulb". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 42 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00142-5. PMID 12668289.

- ^ Johnson BA, Leon M (2000). "Modular representations of odorants in the glomerular layer of the rat olfactory bulb and the effects of stimulus concentration". The Journal of comparative neurology. 422 (4): 496–509. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20000710)422:4<496::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10861522.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Masaoka Y, Satoh H, Akai L, Homma I (2010). "Expiration: The moment we experience retronasal olfaction in flavor". Neurosci Lett. 473 (2): 92–96. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.024. PMID 20171264.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wesson D.W., Wilson D.A. (2010). "Smelling Sounds: Olfactory-auditory convergence in the olfactory tubercle". J Neurosci. 30 (8): 3013–1021. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6003-09.2010. PMC 2846283. PMID 20181598.

- ^ Scientific American, Making scents of sounds Lynne Peeples, 23 February 2010, accessed 25 February 2010

- ^ Hirsch, Alan R. (2003) Life's a Smelling Success

- ^ Gilbert, Avery (2008). "Freaks, Geeks, and Prodigies". What the Nose Knows. Crown Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4000-8234-6.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/03/science/03find.html

Further reading

- Gordon M.s Shepherd Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters New York : Columbia University Press, 2012 ISBN 978-0-231-15910-4

External links

- Mammalian Odor Perception through Genetics

- Research on Interesting Questions About Smells

- Insect Olfaction of Plant Odour

- Smells and Odours - How Smell Works at thenakedscientists.com

- Olfaction at cf.ac.uk

- Structure-odor relations: a modern perspective at flexitral.com (PDF)

- Chirality & Odour Perception at leffingwell.com

- ScienceDaily Artille 08/03/2006, Quick -- What's That Smell? Time Needed To Identify Odors Reveals Much About Olfaction at sciencedaily.com

- Scents and Emotions Linked by Learning, Brown Study Shows at brown.edu.com

- Sense of Smell Institute at senseofsmell.org. Research arm of international fragrance industry's The Fragrance Foundation

- Olfactory Systems Laboratory at Boston University

- Smells Database

- Burghart

- Olfaction and Gustation, Neuroscience Online (electronic neuroscience textbook by UT Houston Medical School)