Rock music in Russia

| Music of Russia | ||||||||

| Genres | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific forms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional music | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Rock and roll became known in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and quickly broke free from its western roots. According to many music critics, its "golden age" years were the 1980s (especially the era of perestroika), when the Soviet underground rock bands could release their records officially. The great majority of the bands perform in the Russian language.

History

The early 1960s: Local bard music and first western influences

Prior to the late sixties, music in the Soviet Union was divided into two groups: music published by state record company Melodiya, and everything else.[1] Under this second group were the bards, underground folk singer–songwriters.

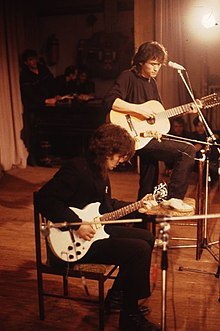

Bards such as Vladimir Vysotsky[2] and Bulat Okudzhava[3] were among the many artists who created the style which is referred to as "author's song" (авторская песня), mostly played on unaccompanied acoustic guitar and characterized by a strong accent on lyrics that sometimes carried a subversive meaning. Their music was often suppressed by the government, and yet enjoyed massive popularity, with Vysotsky becoming a highly popular cinema and theatre actor and an iconic figure of the times.

Meanwhile, some Western music was either being smuggled across the border or released by Melodiya as part of what essentially was state-run media piracy, with The Beatles taking a firm place in Soviet popular culture, and artists such as The Rolling Stones and Deep Purple completing a somewhat distorted picture of Western music.[4]

The first rock bands in the Soviet Union appeared on the scene in the early sixties in Moscow, and they were heavily influenced by The Beatles.[4]

The late 1960s and 1970s: First signs

The ive bands grew popular in spite of governmental restrictions. This continued into the 1980s, when native bands gained some success, but were still hampered by state regulators who would not allow them to be officially recorded, and placed restrictions on lyrical content.

Guitar-driven bands evolved during this time, including Leningrad-based Pojuschie Gitary (the singing guitars) and Belarusian Pesnyary. These bands started the VIA (Вокально-Инструментальный Ансамбль Vokal'no-Instrumental'nyy ansambl' -- Vocal-Instrumental Ensemble) movement, and were followed by others, such as Tcvety, Golubiye Gitary and Sinyaya Ptica.[1][4] At the same time Mashina Vremeni in Moscow and Aquarium in Leningrad started as nominally amateur bands and soon became popular, performing underground concerts.

In the early 1970s Yuri Morozov invented a kind of Russian psychedelic rock, using elements of progressive rock and Ethnic Russian music as well. His sound influenced DDT, Aquarium, Chizh & Co, and many others, while he worked with them as a sound engineer.

Another notable artist who started his activity at the same time is Alexander Gradsky, who fused bard music with rock. There was no protest against the Soviet government in the lyrics he sang, so he was able to release records through Melodiya and millions of them were sold all over the country.

The 1980s: "Classic" Russian rock

In the 1980s an underground scene of rock artists emerged that based their style on a mix of Western rock music (particularly those from the 1960s and 70s but also, increasingly, those that emerged out of the Western punk rock and New Wave) and the Russian bard tradition. Such bands as Alisa, Agata Kristi, Autograph, Kino, Mashina Vremeni, Nautilus Pompilius, Aquarium, Krematorij, Grazhdanskaya Oborona, Voskreseniye, Secret, Piknik, and DDT were influential in the development of the genre, with the consequent artists influenced by their style.[4]

Russian rock was also influenced by the Russian art group Mitki and the Western hippies.

In 1980 a big Rock festival was held in Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, named Spring Rhythms. Tbilisi-80. Almost all the performers and prize-winners at the festival were rock groups from the Russian SFSR. It was the first official rock festival in the Soviet Union.

The lyrics of the Soviet rock bands often dealt with the darkest sides of the 80s Soviet life such as domestic violence, alcoholism (an infamous song by Nautilus Pompilius contained the lines "Alain Delon drinks a double bourbon/Alain Delon doesn't drink eau de cologne" as a sarcastic contrast to the alcoholic father described in the song and an indictment of the escapist attitudes of state-run media) and crime, and often carried a hidden political message.

Soviet rock bands bands were consequently ignored by the mainstream radio and television, often reaching audiences only through word of mouth. The monopoly for the music publishing in the USSR belonged to Melodiya, the one and only Soviet record label, and Melodiya had a strict policy against publishing straightforward rock music or underground musicians. Some of the artists (Yuri Shevchuk,[5] Yegor Letov[6] and many others) even had problems with KGB due to their public activities. During the early 1980s Soviet authorities started a heavy pressure on amateur bands, Underground concerts were banned as a sort of illegal commercial activity, while some of music promoters and sound engineers were even imprisoned for earning money from underground concerts. At the same time, several rock clubs were established to allow amateur bands to perform legal concerts.

Many of the 1980s bands are still active and popular among Russian youth. The term Russian rock is often used to refer to the particular sound of these bands.[7]

Various music scenes

In the early- to mid-1980s, several rock clubs were founded in Moscow, Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg). These three cities had their own rock music scene, with friendly collaborations between artists commonplace.

The Leningrad Rock Club was probably the biggest venue,[8] featuring "classic Russian rock" by Aquarium,[9] Kino,[10] Zoopark, Piknik,[11] Alisa,[12] DDT, Televizor, N.E.P., etc.[13] It also included the nascent Russian art rock movement, typified by such bands as Auktyon.

Bands from Sverdlovsk, such as Nautilus Pompilius,[14] Chaif,[15] and Agata Kristi,[16] produced more melodic music making heavy use of keyboards and synthesizers.

Moscow rock bands, such as Aria,[17] Mashina Vremeni,[18] Voskreseniye, Center, Krematorij[19] and Zvuki Mu, were rather different from the others and sometimes more discreet.[20]

The Siberian rock scene began in the 1980s, with such songwriters as Egor Letov (Grazhdanskaya Oborona,[21] Omsk), Kalinov most, Alexander Bashlachev and Yanka Dyagileva. Their music varied from simple lo-fi punk to indie rock (sometimes acoustic), and the core of their songs were the lyrics. Many albums were first self-released and distributed among the fans via trading, then officially re-released years later. Lyrics were often obscene, and the musicians had major problems with the Soviet administration and KGB. Notable acts that were not members of any of the three Rock-Clubs but were highly popular are Rock N' Roll band Secret.

At that time the Russian Heavy metal scene was created thanks to bands like Aria,[22] Chorny Kofe and Master (formed by a few ex-members of Aria).[23]

The glam metal band Gorky Park reached high popularity in the west and was even aired on MTV.

Russian punk's unique style is generally accepted to be most idealized by Grazhdanskaya Oborona and Egor Letov's other projects. The music mixes equal parts Western punk and the traditional Russian influences, with gritty production and extremely charged and political lyrics.

From underground to publicity

The late 1980s were the years of breakthrough for the soviet rock music artists to the wide public. Political and social changes in the country were very important for this process.

The censorship was still present, but not as rigid as it was in the 1970s or early 1980s. It took years for the first Soviet rock bands to enter the media, tour in major concert halls over the USSR, and to release their albums officially.

The situation around rock music changed during the perestroika era. Many Russian rock bands were able to tour and record in Europe and USA for the first time. As a result, in 1989-1991 the situation was completely different from that of 1985. Moscow Music Peace Festival with western rock stars was held in Moscow, Gorbachev accepted Scorpions in Kremlin,[24] and Brian Eno produced an album by Zvuki Mu and Dave Stewart (of Eurythmics fame) produced Radio Silence by Boris Grebenshchikov for the release in the western world.

With Joanna Stingray's initiative, in 1986 the Red Wave compilation was released in the United States. It was a double split album with four bands from Leningrad: Aquarium, Kino, Alisa, and Strannye Igry. One side of vinyl for each band. This compilation was the first official Russian rock release in the west.

Stingray sent copies of the release to Ronald Reagan and Gorbachev, supplied with a statement saying musicians already did what both presidents could not do diplomatically.

Melodiya's reaction was an official release of a record by Aquarium in order to create an illusion that recordings of the band are also widely released in the USSR.[25]

Another important contributor for the breakthrough of Russian rock to the public in the 1980s were television and film. New musical television shows, such as Muzykalny Ring (Музыкальный ринг) and Programma A (Программа "А"), invited national rock artists for interviews and live shows. Several popular films were created in the second half of the 1980s, featuring Russian rock musicians as actors: Igla and Assa featuring Viktor Tsoi and music by Aquarium, Taxi Blues featuring Pyotr Mamonov. The Canadian filmmaker Peter Vronsky travelled to Moscow and Leningrad in February 1988 and shot a series of music videos with Televizor, Aquarium, Nebo i Zemlya, Zvuki Mu and other bands, tied together into a documentary film Russian Rock Underground which brought Russian Rock for the first time to MuchMusic television in Canada and to Italian television.

The 1990s: Post-Soviet era

The beginning of the 1990s are considered to be the end of the "classic" Russian rock era. The two events that mark its end are the death of Viktor Tsoi in 1990, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Nevertheless, the Russian rock sound continued to live and the new Russian rock sound of the '90s was based on it. In 1996 the recording company Moroz started releasing the highly popular series Legends of Russian Rock.

In the mid-late 1990s the radio station Nashe Radio had been created to promote Russian rock artists, broadcasting in all major Russian cities. Nashe Radio notably influenced the auditory taste and helped many artists to gain popularity. The radiostation founded Nashestvie, the largest open-air rock festival of Russian rock music performed yearly since 1999 and always headlined with famous rock acts.

Often aired by Nashe Radio, bands like Splean,[26] Nochniye Snaiperi,[27] Smisloviye Galutzinatzii, Chicherina and Bi-2[28][29] have created a refreshed Russian rock sound which adopted many elements from Alternative rock. Dolphin created a mixture between alternative rock, electronic music and rapcore.

In late 1990s, numerous punk, pop-punk and grunge bands broke through. Probably the most popular was Sektor Gaza, a national Russian folk and horror punk band. Sektor Gaza was first Russian band use of dirty words and dirty short story in its lyrics. Sektor Gaza's style was adopted by Korol i Shut,[30] a horror punk band (headed by Mikhail Gorsheniov and Andrei Knyazev) with fantasy-driven lyrics, but without dirty words and without Russian lyrics in songs. Ska punk was brought to popularity mainly by the band Leningrad, notable of the extensive use of Mat - Russian dirty language - in its lyrics.[31] Other notable punk artists included Pilot, Lumen, 7Rasa, Naiv, Tarakany!, Distemper and Nogu Svelo![16] who also gained major popularity. Many of them developed an original sound and involvement of unconventional instruments like violin.

The Russian instrumental rock artist Victor Zinchuk reached international success with his solo career, and by that brought the Russian instrumental rock scene into a bigger audience.[32]

The western Pop rock sound was introduced by Ilya Lagoutenko's Mumiy Troll,[33] who made their records in the UK under the guidance of UK producers. This less lyrically loaded and more energetic style frequently referred to as rockapops, which was also used by other notable bands such as Zemfira, became prevalent among the younger public.

The 1997 Russian extremely popular films Brother, with its soundtrack featuring the classic Russian rock band Nautilus Pompilius, and its sequel Brother 2, whose soundtrack was compiled from music of many Russian rock artists, brought many young fans to Russian rock.[34]

The 2000s: Further development - current activity

The 2000s in Russian Rock are marked by both a continuance of the '90s and something of a comeback of the classic 80s sound. In the years following the renaissance of Russian cinema and rock, rock in Russia seems to gain enough ground to differentiate widely in various genres.

Alternative metal and metalcore gained wider popularity at that time. In mid-2000s bands like Amatory, Grenouer, Tracktor Bowling, Slot were established and soon arose in fame, being intensively promoted by A-One channel. The channel awarded many of them with Russian Alternative Music Prize.

Russian Alternative rock and Electronic music gained world recognization with the pop duo t.A.T.u., which used elements from those styles, gaining international success.[35][36] Please note however that although sounding 'rock-ish', t.A.T.u must not be mistaken as a part of Russian rock culture. While all other Russian rock bands are (at least originally) self-organized, t.A.T.u is a purely commercial project brought together by pop music producers and considered by most Russian rock fans as "popsa".

Russian Heavy metal scene continued its development with power metal bands like Shadow Host, Catharsis and Epidemia, founded in the 1990s, received more attention. In 2002 Valery Kipelov split from Aria, and with more ex-members of Aria he formed a new band called Kipelov, which soon compared itself to Aria in popularity.

The underground pagan metal scene, based on Slavic pagan traditions, has grown widespread with such bands as Temnozor, Arkona, Pagan Reign and Butterfly Temple being noted by enthusiasts outside of Russia.[37] Underground scene is not limited to pagan metal, for example Orgia Pravednikov, which employs various rock styles, is also absent on commercial radio. Its music and lyrics are influenced both by Christian (and other) spirituality and many folk elements.

Folk rock music had a revival following Pelageya's and Melnitsa's rise from underground acts to constantly radio-aired bands.[38] Some acts (Bugotak, H-Ural, etc.) became popular performing songs in minority languages like the (Buryat and Khanty, etc.).

Though the Russian Progressive rock scene had existed since the 1970s, it was the 2000s when it entered the public eye of Russian rock fans, with bands like Little Tragedies[39] and The Gourishankar being its most obvious representatives. Since 2001 a prog-music festival named InProg was held almost yearly in Moscow. Its popularity constantly grew and in 2005 it turned from a local festival into an international one.

The Russian instrumental rock scene with bands like EXIT project, Disen Gage, Dvar and Kostarev Group also received more recognition at that time.[39]

The 2005 Live 8 concert that took place in Moscow featured mainly Russian rock artists.

The rockapops phenomenon from the 1990s continued to gain popularity in the 2000s with new bands like Zveri arriving.

Bard rock of the 2000s is represented by such act as Gollandiya, a trio from Saint Petersburg.

Industrial rock of the 2010s is represented by such act as KanZer, a alternative-duet from Saint Petersburg. The main example of industrial music in Russia, is the single "Run". This genre industrial is just starting to develop in Russia.

Characteristics

Fans of Russian Rock would frequently refer to most of the music on MTV Russia dismissively as "popsa", a dichotomy that appeared in the '80s when government controlled radio and TV stations would air only politically harmless music by performers such as Philipp Kirkorov.[40] The lines are still quite clearly drawn, with bands such as Nogu Svelo! - who recorded a song with pop-singer Nataliya Vetlitskaya - being an anomaly.

In contrast to Western rock, Russian rock is often said to have less drive; it is characterized by different rhythms, instruments and more involved lyrics. Unconventional instruments have often been used in addition to the standard electric guitars and drums (very often violin and wind instruments).[41]

Another characteristic of Russian Rock is being partly Folk rock. Very often Russian Rock songs, especially those of the classic 80s bands, talk about national themes and feature elements from Russian folk music. Aquarium, DDT and Yuri Morozov could be used as examples for that.[42]

Considering its poetic roots (Russian literature, bard music), it is not a big surprise that lyrics play a far larger role in Russian rock than Western rock. Vocal melody is sometimes eschewed in favor of a more impassioned delivery (Viktor Tsoi, the lead singer of Kino, pioneered a characteristically strained, monotonous style of singing that has been imitated by many).

Russia has always been facing both East and West with its double-headed Eagle on the coat-of-arms. The Eastern derivative in the Russian rock came with soundtracks from movies like Day Watch that had Tamerlan's legend of the Chalk of Destiny at its roots. Russian rock expressively used and integrated elements from culture, as well as Western and Eastern (especially countries of the USSR).

Yngvar Bordrewich Steinholt[43] (University of Tromsø, Norway) has written a PhD thesis in English that was printed by The Mass Media Music Scholars Press titled "Rock in the Reservation" (2004) about the Leningrad Rock Club. It also touched upon the history of rock in Russia and its counter-cultural tendencies.

Wordplay

In Russian, the original meaning of word "рок" is "fate" or "doom". The word is used almost exclusively in fiction, especially poetry (more widely used synonym is "судьба"). These correlates with poetic roots of Russian rock and its attention to "serious" topics.

The wordplay is used in the song "This is Fate" (Russian: Это рок) from Aria's debut album "Mania Velichia".[44]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Владимир Высоцкий (Vladimir Vysotskiy ): Russmus:Bladimir Vysotskiy

- ^ Булат Окуджава (Bulat Okudzhava): Russian modern:bards Artist

- ^ a b c d Рок-Музыка В России

- ^ Brief biography of Yuri Shevchuk (in Russian)

- ^ History of Grazhdanskaya Oborona (in Russian), «Музыкальная Газета», Minsk, 1998

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ a b Russian Studies

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Old-time rock 'n' roll/ The Scorpions are sweeping across America

- ^ Aqaurium Guide, 1986/06/27, "Red Wave" (in Russian)

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Ночные Снайперы (Nochnye Snaypery): Russian modern:rock/pop Artist

- ^ Би-2 – Music at Last.fm

- ^ Би-2 (Bi-2): Russian modern:rock/pop Artist

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Victor Zinchuk::Biography

- ^ The legends of Russian Rock Music :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Зоил __ Где Брат Твой?

- ^ t.A.T.u. Biography (Rock Musicians) — Infoplease.com

- ^ 2006 - All about group t.A.T.u - Site

- ^ Metal-Nightfall review for Temnozor Template:Fr icon

- ^ Moscow Times: Russian Revival 22.03.2007 by Vladimir Kozlov

- ^ a b журнал "Автозвук"

- ^ "ВРЕМЯ Z" - журнал для интеллектуальной элиты общества

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre

- ^ Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt´s homepage - Yngvar Bordewich Steinholts hjemmeside

- ^ "This is Fate" lyrics Template:Ru icon

External links

- Largest and free mp3 archive of different russian rock gentres, oldies and new most important bands. Site in english

- List of Russian bands

- Russian Music on the Net: Site about Modern Russian music with lots of Rock bands

- History of Rock Music In Russia

- A list of Russian rock bands who reached a legendary status

- Annotated library of modern Russian music - including Russian rock

- A quick overview about Russian rock Template:Ru icon

- Information about Russian rock history Template:Ru icon