Second Epistle of Peter

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Peter in the Bible |

|---|

|

| In the New Testament |

| Other |

2 Peter, also known as the Second Epistle of Peter and abbreviated as 2 Pet.,[a] is an epistle of the New Testament written in Koine Greek. It identifies the author as "Simon Peter" (in some translations, 'Simeon' or 'Shimon'), a bondservant and apostle of Jesus Christ" (2 Peter 1:1). The epistle is traditionally attributed to Peter the Apostle, but most scholars consider the epistle pseudepigraphical (i.e., authored by someone one or more of Peter's followers, using Peter as a pseudonym)[3][4][5][6][7] Scholars estimate the date of authorship anywhere from AD 60 to 150.

Authorship and date

[edit]According to the Epistle itself, it was composed by the Apostle Peter, an eyewitness to Jesus' ministry. 2 Peter 3:1 says "This is now the second letter I have written to you"; if this is an allusion to 1 Peter, then the audience of the epistle may have been the same as it was for 1 Peter, namely, various churches in Asia Minor (see 1 Peter 1:1).

The date of composition has proven to be difficult to determine. Taken literally, it would have been written around AD 64–68, as Christian tradition holds Peter was martyred in the 60s by Nero, and also because Peter references his approaching death in 2 Peter 1:14 ("since I know that the putting off of my body will be soon, as our Lord Jesus Christ made clear to me").[8]

The questions of authorship and date are closely related. Scholars consider the epistle to have been written anywhere between c. AD 60-150, with "some reason to favour" a date between 80-90.[9] Dates suggested by various authors include:

- c. 60 (Charles Bigg)[10]

- 63 (Giese, Wohlenberg)[11][12]

- 64 – 110 (Davids)[13]

- Mid 60s (Harvey and Towner, M. Green, Moo, Mounce)[14][15][16][17]

- c. 70 or 80 (Chaine)[18]

- 75 – 100 (Bauckham, perhaps about 80–90)[19]

- 80 – 90 (Duff)[9]

- c. 90 (Reicke, Spicq)[20][21]

- Late first or early second century (Perkins, Harrington, Werse)[22][23][24]

- c. 100 (Schelkle)[25]

- 100 – 110 (Knoch, Kelly)[26][27]

- 100 – 125 (James, Vogtle, Paulsen)[28][29][30]

- 100 – 140 (Callan, perhaps about 125)[31]

- 130 (Raymond E. Brown, Sidebottom)[32][33]

- 150 (L. Harris)[34]

The scholarly debate can be divided into two parts: external and internal evidence. The external evidence for its authenticity, although feasible, remains open to criticism. (There is debate as to whether 2 Peter is being quoted or the other way around.) Much of this debate derives from Professor Robert E. Picirilli's article "Allusion to 2 Peter in the Apostolic Fathers," which compiles many of the allusions by the Apostolic Fathers of the late first and early second centuries, thus demonstrating that 2 Peter is not to be considered a second-century document.[35] Despite this effort, scholars such as Michael J. Gilmour, who consider Picirilli's evidences to be correct, disagree with classifying the work as authentic but rather as a pseudepigrapha, arguing among many other things that Paul (2 Thessalonians 2:1–2) had to warn against contemporary pseudo-Pauline writers.[36]

The internal debate focuses more on its style, its ideology, and its relationship to the other works and stories. Some of the internal arguments against the authenticity of 2 Peter have gained significant popularity since the 1980s. One such argument is the argument that the scholar Bo Reicke first formulated in 1964, where he argued that 2 Peter is clearly an example of an ancient literary genre known as a 'testament', which originally arose from Moses' farewell discourse in Deuteronomy.[37][b][c] Richard J. Bauckham, who popularized this argument, wrote that the 'testament' genre contains two main elements: ethical warnings to be followed after the death of the writer and revelations of the future. The significant fact about the 'testament' genre was not in its markers but in its nature; it is argued that a piece of 'testament' literature is meant to "be a completely transparent fiction."[41] This argument has its detractors, who classify it as a syllogism.[42][43][44][45][46] Others characterize the writing as a 'farewell speech' because it lacks any semblance of final greetings or ties with recipients.[47]

One of the questions to be resolved is 2 Peter's relationship with the Pauline letters since it refers to the Pauline epistles and so must postdate at least some of them, regardless of authorship. Thus, a date before AD 60 is improbable. Further, it goes as far as to name the Pauline epistles as "scripture"—one of only two times a New Testament work refers to another New Testament work in this way—implying that it postdates them by some time.[48] Various hypotheses have been put forward to improve or resolve this issue; one notable hypothesis is that the First Epistle of Clement (c. AD 96), by citing as Scripture several of the Pauline letters,[49] was inspired by 2 Peter because it was considered authentic. This would mean that even the recipients of 1 Clement, the inhabitants of Corinth, would have also considered it authentic, which would indicate that the letter must have been in circulation long before that time.[50] The earliest reference to a Pauline collection is probably found in Ignatius of Antioch around AD 108.[51][52]

Another debate is about its linguistic complexity and its relationship with 1 Peter. According to the scholar Bart D. Ehrman, the historical Peter could not have written any works, either because he was "unlettered" (Acts 4:13) or because he was a fisherman from Capernaum, a comparatively small and probably monolingual town, in a time and province where there was little literacy.[53] Bauckham addresses the statistical differences in the vocabulary of the two writings, using the data given by U. Holzmeister's 1949 study;[54] 38.6 percent of the words are common to 1 and 2 Peter. 61.4 percent peculiar to 2 Peter, while of the words used in 1 Peter, 28.4 percent are common to 1 and 2 Peter, 71.6 percent are peculiar to 1 Peter. However, these figures can be compared with other epistles considered authentic,[55] showing that pure statistical analysis of this type is a weak way of showing literary relationship.[56][57][58] Bauckham also notes that "the Greek style of Second Peter is not to the taste of many modern readers, at times pretentiously elaborate, with an effort at pompous phrasing, a somewhat artificial piece of rhetoric, and 'slimy Greek'"; contrary to the style of the first epistle, "2 Peter must relate to the 'Asiatic Greek.'"[59] The crux of the matter is how these differences are explained. Those who deny the Petrine authorship of the epistle, such as, for example, Kelly, insist that the differences show that First and Second Peter were not written by the same person.[60] Others add that 2 Peter was a specific type of pseudepigraphy common and morally accepted at the time, either because it was a testamentary genre or because the works of the disciples could bear the names of their masters without any inconvenience.[61][62][d]

Those who defend Petrine authorship often appeal to the different amanuenses or secretaries Peter used to write each letter, as first suggested by Jerome.[63][64][65] Thomas R. Schreiner criticizes people who regard arguments in favor of the authenticity of 2 Peter as mere arguments of religious conservatives who impotently try to invent arguments to support authenticity. People of this mindset, according to Schreiner, object to the claim that different secretaries may have been used but then claim that the corpus of the two letters is too small to establish stylistic variation. Schreiner states:

When we examine historical documents, we are not granted exhaustive knowledge of the circumstances in which the document came into being. Therefore, we must postulate probabilities, and in some cases, of course, more than one scenario is likely. Moreover, in some cases the likely scenarios are not internally contradictory, but both constitute plausible answers to the problem posed. Suggesting more than one solution is not necessarily an appeal to despair, but can be a sign of humility.[66]

The scholar Simon J. Kistemaker believes that linguistically "the material presented in both documents provides substantial evidence to indicate that these letters are the product of a single author."[67] However, this view is very much in the minority. Most biblical scholars have concluded Peter is not the author, considering the epistle pseudepigraphal.[3][68][69][70][34][48] Reasons for this include its linguistic differences from 1 Peter, its apparent use of Jude, possible allusions to second-century gnosticism, encouragement in the wake of a delayed parousia, and weak external support.[71]

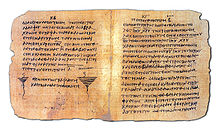

Early surviving manuscripts

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter are:

Greek

[edit]- Papyrus 72 (3rd/4th century)[72]

- Codex Vaticanus (B or 03; 325–50)

- Codex Sinaiticus (א or 01; 330–60)

- Codex Alexandrinus (A or 02; 400–40)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (C or 04; c. 450; partial)[73]

- Papyrus 74 (7th century; extant verses 3:4, 3:11, 3:16)

Latin

[edit]- Codex Floriacensis (h; 6th century Old-Latin; partial)[74]

Relationship with the Epistle of Jude

[edit]There is an obvious relationship between the texts of 2 Peter and the Epistle of Jude, to the degree that one of them clearly had read the other and copied phrases, or both had read some lost common source.[75] The shared passages are:[76]

| 2 Peter | Jude |

|---|---|

| 1:5 | 3 |

| 1:12 | 5 |

| 2:1 | 4 |

| 2:4 | 6 |

| 2:6 | 7 |

| 2:10–11 | 8–9 |

| 2:12 | 10 |

| 2:13–17 | 11–13 |

| 3:2-3 | 17-18 |

| 3:14 | 24 |

| 3:18 | 25 |

In general, most scholars believe that Jude was written first, and 2 Peter shows signs of adapting phrases from Jude for its specific situation.[77]

Canonical acceptance

[edit]The earliest undisputed mention of 2 Peter is by the theologian Origen (c. 185–254) in his Commentary on the Gospel of John, although he marks it as "doubted"/"disputed".[77] Origen mentioned no explanation for the doubts, nor did he give any indication concerning the extent or location. Donald Guthrie suggests that "It is fair to assume, therefore, that he saw no reason to treat these doubts as serious, and this would mean to imply that in his time the epistle was widely regarded as canonical."[78] Acceptance of the letter into the canon did not occur without some difficulty; however, "nowhere did doubts about the letter's authorship take the form of definitive rejection."[78]

Origen, in another passage, has been interpreted as considering the letter to be Petrine in authorship.[79] Before Origen's time, the evidence is inconclusive;[80] there is a lack of definite early quotations from the letter in the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, though possible use or influence has been located in the works of Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 211), Theophilius (d. c. 183), Aristides (d. c. 134), Polycarp (d. 155), and Justin (d. 165).[81][82][35]

Robert E. Picirilli observed that Clement of Rome linked James 1:8, 2 Peter 3:4, and Mark 4:26 in 1 Clement 23:3.[35]: 59–65 Richard Bauckham and Peter H. Davids also noted the reference to “Scripture” in 1 Clement 23:3 matched 2 Peter 3:4, but make it dependent on a common apocalyptic source, which was also used in 2 Clement 11:2.[83][84]

Carsten Peter Thiede adds to Picirilli's work authors such as Justin and Minucius Felix who would use 2 Peter directly and a new reference in Clement of Rome (1 Clem. 9.2 = 2 Pet. 1.17).[85]

2 Peter seems to be quoted amongst apocryphal literature in Shepherd of Hermas (AD 95–160),[86][87] Apocalypse of Peter (c. AD 125–135),[88][89][90][91][92] the Gospel of Truth (AD 140–170), and the Apocryphon of John (AD 120–180).[93]

Eusebius (c. 275–339) professed his own doubts (see also Antilegomena), and is the earliest direct testimony of such, though he stated that the majority supported the text, and by the time of Jerome (c. 346–420) it had been mostly accepted as canonical.[94]

The Peshitta, the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition, does not contain the Second Epistle of Peter and thus rejects its canonical status.[95]

Content

[edit]In both content and style this letter is very different from 1 Peter. Its author, like the author of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, is familiar with literary conventions, writing in a more elevated Koine Greek than, for example, Paul's writings or the Gospel of Mark.[96] Gorgianic figures are used which are characteristic of Asian rhetoric (Asianism),[97][98] with style similar to that of Ignatius and the Epistle to Diognetus.[99] This leads some scholars to think that, like 1 Peter, the letter is addressed to Gentile Christians in Asia Minor.[100][101][102]

The epistle presciently declares that it is written shortly before the apostle's death (1:14), an assertion that may not have been part of the original text. Arguments for and against the assertion being original are based largely on the acceptance or rejection of supernatural intervention in the life of the writer.[103]

The epistle contains eleven references to the Old Testament. In 3:15-16 a reference is made to one of Paul's epistles, which some have identified as 3:10a with 1 Thess. 5:2; 3:14 with 1 Thess. 5:23.[e]

The author of 2 Peter had a relationship with the Gospel tradition, mainly in the Transfiguration of Jesus, 1:4 with Mark 9:1; 1:11 with Mark 9:1; 1:16,18 with Mark 9:2-10; 1:17 with Matthew 17:5; 1:19 with Mark 9:4;[105] and in the promise of the Second Coming, 3:10b with Mark 13:31 or Luke 21:33.[106]

The book also shares a number of passages with the Epistle of Jude, 1:5 with Jude 3; 1:12 with Jude 5; 2:1 with Jude 4; 2:4 with Jude 6; 2:5 with Jude 5; 2:6 with Jude 7; 2:10–11 with Jude 8–9; 2:12 with Jude 10; 2:13–17 with Jude 11–13; 2:18 with Jude 16; 3:2f with Jude 17f; 3:3 with Jude 18; 3:14 with Jude 24; and 3:18 with Jude 25.[107] Because the Epistle of Jude is much shorter than 2 Peter, and due to various stylistic details, the scholarly consensus is that Jude was the source for the similar passages of 2 Peter.[107][108]

Tartarus is mentioned in 2 Peter 2:4 as devoted to the holding of certain fallen angels. It is elaborated on in Jude 6. Jude 6, however, is a clear reference to the Book of Enoch. Bauckham suggests that 2 Peter 2:4 is partially dependent on Jude 6 but is independently drawing on paraenetic tradition that also lies behind Jude 5–7. The paraenetic traditions are found in Sirach 16:7–10, Damascus Document 2:17–3:12, 3 Maccabees 2:4–7, Testament of Naphtali 3:4–5, and Mishna Sanhedrin 10:3.[109]

Outline

[edit]Chapter 1

[edit]The chapters of this epistle show a triangular relationship between Christology (chapter 1), ethics (chapter 2) and eschatology (chapter 3).

At the beginning of chapter 1, the author calls himself "Simeon Peter" (see Acts 15:14). This detail, for the scholar Rob. van Houwelingen, is evidence of the authenticity of the letter.[110] The letter gives a list of seven virtues in the form of a ladder; Love, Brotherly affection, Godliness, Steadfastness, Self-control, Knowledge, and Excellence.[111] Through the memory of Peter (1:12–15), the author encourages the addressees to lead holy and godly lives (11b); in verse 13 the author speaks of righteousness (being just) in a moral sense and in verse 14 his line of argument reaches a climax as the addressees are encouraged to do all they can to be found blameless (1 Thess 5:23). In short the author is concerned to encourage his addressees to behave ethically without reproach (1:5–7; 3:12–14), probably because of the impending parousia (Second Coming), which will come like a thief in the night (3:10; 1 Thess 5:2).[112]

Chapter 2

[edit]In this chapter the author affirms that, false teachers have arisen among the faithful to lead them astray with "destructive heresies" and "exploit people with false words" (2:1–2). Just as there were false prophets in ancient times, so there would be false teachers,[113] moreover false prophets sheep's clothing were one of the prophecies of Jesus [Matt. 7:15], to which the author of this letter together with the author of 1 John refers [1 John 4:1].[114] False teachers are accused of "denying the Lord who bought them" and promoting licentiousness (2:1–2). The author classifies false teachers as "irrational animals, instinctive creatures, born to be caught and destroyed" (2:12). They are "spots and stains, delighting in their dissipation" with "eyes full of adultery, insatiable for sin… hearts trained in covetousness" (2:13–14).[113] As a solution 2 Peter proposes in the following chapter tools such as penance, aimed at purging sins, and the reactualization of the eschatological hope, to be expected with attention, service and perseverance.[115] This chapter all likelihood adapts significant portions of the Epistle of Jude.[116][117][118][119]

The ethical goal is not to fall that debauchery, errors and to have hope, this is promoted with many stories of how God rescues the righteous while holding back the unrighteous for the day of judgment, the story of Noah, the story of Lot in Sodom and Gomorrah (2:6–8) and the story Balaam, son of Bosor (2:15–16) are used as a warning.

2 Peter 2:22 quotes Proverbs 26:11: "As a dog returns to his vomit, so a fool repeats his folly."

Chapter 3

[edit]

The fundamental of this chapter is the authoritative Christian revelation. The revelation is found in a two-part source (3:2). There is little doubt that the "words spoken beforehand by the holy prophets" refers to the OT writings, either in part or in whole.[120][121] Then the author mentions the second source of revelation, the "commandment of the Lord" spoken by "your apostles." It is remarkable that this two-part authority includes an obvious older means "words spoken beforehand" as well as an obvious newer half, the apostolically mediated words (words about Jesus). One could be forgiven if he sees here a precursor to a future "old" and "new" Testament.[122] This juxtaposition of prophet and apostle as a two-part revelatory source is not first found in 3:1–2, but in 1:16–21.[121]

Another remarkable feature of this chapter is that the author presupposes that his audience is familiar with a plurality of apostles ("how many" is unclear), and, moreover, that they have had (and perhaps still have) access to the teaching of these apostles. One cannot "remember" teaching that they have not received. Of course, this raises difficult questions about the precise medium (oral or written) by which the public received this apostolic teaching. However, near the end of this chapter, the means by which the audience at least received the apostle Paul's teaching is expressly stated. We are told that the audience knew the teachings of "our beloved brother Paul" (3:15) and that they knew them in written form: "Paul also wrote to you according to wisdom as he does in all his letters" (3:16), the "also" being the key word since in the first verse of the chapter the author referred to another written apostolic text, namely his first epistle (1 Peter): considering part of the "Scriptures" not only the OT prophets, but also Paul and the author himself,[123] from the Pauline corpus the author may have known 1 and 2 Thessalonians, Romans, Galatians, and possibly Ephesians and Colossians.[124][125] Thought on Christian revelation is also located in other early authors, namely Clement of Rome, Ignatius, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, and in the work 2 Clement.[126]

In the middle of the chapter is the explanation for the delay in Jesus' return (3:9); Jesus' delay is only to facilitate the salvation of the "already faithful" who may at times waver in their faith or have been led astray by false teachers (2:2–3). God is delaying to make sure that "all" have had sufficient time to secure their commitment (or return) to the gospel, including the false teachers. The remaining verses provide details about the coming day of the Lord along with the exhortation that flows seamlessly into the conclusion of the letter. The instruction offered here (3:11–13) echoes that of Jesus who called his disciples to await the consummation of his kingdom with attention, service and perseverance (Mt 24-25; Mk 13:3–13, 32–37; Lk 18:1–30; 21:1–38). Taken together with the final verses (3:14–18), here again the author expresses the concern that believers secure their eternal place in God's new creation by embracing lives that foster blessing and even hasten God's coming day.[127]

2 Peter 3:6 quotes Genesis 7:11–12. 2 Peter 3:8 quotes Psalm 90, specifically 90:4.[128]

See also

[edit]- First Epistle of Peter

- Textual variants in the Second Epistle of Peter

- Universal destination of goods

Notes

[edit]- ^ The work is also called the Second Letter of Peter.[1][2]

- ^ Within the New Testament it is speculated that 2 Timothy, John 13-17, Luke 22:21-38, and Acts 20:18-35 are also farewell discourses or testamentary works.[38][39]

- ^ In addition to the end of Deuteronomy within the Old Testament, it is speculated that Genesis 47:29–49:33 and 1 Samuel 12 are also farewell discourses.[40]

- ^ Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem. 4.5.3-4; That which Mark edited is stated to be Peter’s [Petri affirmetur], whose interpreter Mark was. Luke’s digest also they usually attribute to Paul [Paulo adscribere solent]. It is permissible for the works which disciples published to be regarded as belonging to their masters [Capit magistrorum videri quae discipuli promulgarint].

- ^ The alleged citation of 1 Thess 5:2 in 2 Pet 3:10 is a disputed allusion. Duane F. Watson, Terranee Callan, and Dennis Farkasfalvy identify the allusion to 1 Thessalonians. Michael J. Gilmour, on the other hand, disputes the identification of the allusion.[104]

References

[edit]- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 1018. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Bible Book Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Brown, Raymond E., Introduction to the New Testament, Anchor Bible, 1997, ISBN 0-385-24767-2. p. 767 "the pseudonymity of II Pet is more certain than that of any other NT work."

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Harper Collins. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-06-182514-9.

Evidence comes in the final book of the New Testament to be written, 2 Peter, a book that most critical scholars believe was not actually written by Peter but by one of his followers, pseudonymously.

- ^ Duff 2007, p. 1271.

- ^ Davids, Peter H (1982). Marshall, I Howard; Gasque, W Ward (eds.). The Epistle of James. New International Greek Testament Commentary (repr. ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 0-80282388-2.

- ^ Evans, Craig A (2005). Evans, Craig A (ed.). John, Hebrews-Revelation. Bible Knowledge Background Commentary. Colorado Springs, CO: Victor. ISBN 0-78144228-1.

- ^ Bauckham, RJ (1983), Word Bible Commentary, Vol. 50, Jude-2 Peter, Waco.

- ^ a b Duff, J. (2001). 78. 2 Peter, in John Barton and John Muddiman (ed.), "Oxford Bible Commentary". Oxford University Press. p. 1271

- ^ Bigg, C. (1901) "The Epistle of St Peter and Jude", in International Critical Commentary. pp. 242-47.

- ^ Giese. C. P. (2012). 2 Peter and Jude. Concordia Commentary. St Louis: Concordia. pp. 11.

- ^ Wohlenberg, G. (1915). Der erste und zweite Petrusbrief, pp. 37.

- ^ Davids, P. H. (2006). The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude. (PNTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 130-260. at. 130-131.

- ^ Harvey and Towner. (2009). 2 Peter & Jude. pp. 15.

- ^ Green, M. (1987). Second Epistle General of Peter and the Epistle of Jude. An Introduction and Commentary. Rev. ed. TNTC. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. pp. 47.

- ^ Moo, D. J. (1996). 2 Peter and Jude. NIVAC. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. pp. 24-25.

- ^ Mounce. (1982). A Living Hope. pp. 99.

- ^ Chaine, J. (1943). Les Epitres Catholiques. pp. 34.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 157-158.

- ^ Reicke, B. (1964). James, Peter and Jude. pp. 144 -145.

- ^ Spicq, C. (1966). Epitres de Saint Pierre. pp. 195.

- ^ Perkins, P. (1995). First and Second Peter. pp. 160.

- ^ Harrington, D. J. (2008). “Jude and 2 Peter”. pp. 237.

- ^ Werse, N. R. (2016). Second Temple Jewish Literary Traditions in 2 Peter. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Vol. 78, No. 1. pp. 113.

- ^ Schelkle, K. H. (1964). Die Petrusbriefe. pp. 178-179.

- ^ Knoch, O. (1998). Erste und Zweite Petrusbrief. pp. 213.

- ^ Kelly, J. N. D. (1969). Epistles of Peter and of Jude, The (Black's New Testament Commentary). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic. pp. 237.

- ^ James, M. R. (1912). Second Epistle General of Peter. pp. 30.

- ^ Vogtle, A. (1994). Der Judasbrief/Der 2. Petrusbrief. pp. 237.

- ^ Paulsen, H. (1992). Der Zweite Petrusbrief und der Judasbrief. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 94.

- ^ Callan. (2014). Acknowledging the Divine Benefactor: The Second Letter of Peter. James Clarke & Company pp 36.

- ^ R. E. Brown 1997, 767.

- ^ Sidebottom, E. M. (1982) James, Jude, 2 Peter. New Century Bible Commentary. Eerdmans Publishing Co. Grand Rapids-Michigan. pp. 99.

- ^ a b Stephen L. Harris (1980). Understanding the Bible: a reader's guide and reference. Mayfield Pub. Co. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-87484-472-6.

Virtually no authorities defend the Petrine authorship of 2 Peter, which is believed to have been written by an anonymous churchman in Rome about 150 C.E.

- ^ a b c Picirilli, Robert E. (May 1988). "Allusions to 2 Peter in the Apostolic Fathers". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 10 (33): 57–83. doi:10.1177/0142064X8801003304. S2CID 161724733.

- ^ Gilmour, Michael. J. (2001), "Reflections on the Authorship of 2 Peter" EvQ 73. Pp. 298-300

- ^ Reicke 1964, 146.

- ^ Collins, Raymond (2002). 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 182–83.

- ^ Bauckham, R. J. (2010). The Jewish World Around the New Testament. Baker Academic. p. 144.

- ^ John Reumann (1991). "Two Blunt Apologists for Early Christianity: Jude and 2 Peter"; Variety and Unity in New Testament Thought. Oxford Scholarship Online.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 131–33.

- ^ Thomas R. Schreiner, 2003, 1, 2 Peter, Jude, NAC, Nashville, TN: Holman Reference), pp. 266–75, at 275.

- ^ Green, Gene (2008). Jude and 2 Peter. Baker Academic, pp. 37–38.

- ^ P. H. R. Van Houwelingen (2010), “The Authenticity of 2 Peter: Problems and Possible Solutions.” European Journal of Theology 19:2, pp. 121–32.

- ^ J. Daryl Charles, 1997, “Virtue amidst Vice: The Catalog of Virtues in 2 Peter 1,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement 150, Sheffield, ENG: Academic Press, pp. 75.

- ^ Mathews, Mark. D. (2011). The Genre of 2 Peter: A Comparison with Jewish and Early Christian Testaments. Bulletin for Biblical Research 21.1: pp. 51–64.

- ^ Reumann 1991.

- ^ a b Dale Martin 2009 (lecture). "24. Apocalyptic and Accommodation" on YouTube. Yale University. Accessed 22 July 2013. Lecture 24 (transcript)

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, Canon of the New Testament (Oxford University Press) 1987:42–43.

- ^ E. Randolph Richards. (1998). The Code and the Early Collection of Paul's Letters. BBR 8. PP. 155-162.

- ^ Duane F. Watson, Terrance D. Callan. (2012). First and Second Peter (Paideia: Commentaries on the New Testament). Baker Books.

- ^ Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians 12:2 and Epistle of Ignatius to the Romans 4:3.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God: Why the Bible's authors are not who we think they are. Harper One. p. 52–77; 133–141. ISBN 9780062012616. OCLC 639164332.

- ^ Holzmeister, U. (1949). Vocabularium secundae espitolae S. Petri erroresque quidam de eo divulg ati. Biblica 30:339-355.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 144. “These percentages do not compare badly with those for 1 and 2 Corinthians: of the words used in 1 Corinthians, 40.4 percent are common to 1 and 2 Corinthians, 59.6 percent are peculiar to 1 Corinthians; of the words used in 2 Corinthians, 49.3 percent are common to 1 and 2 Corinthians, 50.7 percent are peculiar to 2 Corinthians.”

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger. (1972). Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha. Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 91, No. 1 (Mar., 1972), pp. 3-24 at. 17.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger. (1958). A Reconsideration of Certain Arguments Against the Pauline Authorship of the Pastoral Epistles. The Expository Times 1970; pp. 91-99.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 144.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 138.

- ^ Kelly 1993, 237.

- ^ Bauckham, RJ. (1988). Pseudo-Apostolic Letters. Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 107, No. 3 (Sep., 1988), pp. 469-494 (26 pages). at. 489.

- ^ Armin D. Baum. (2017). Content and Form: Authorship Attribution and Pseudonymity in Ancient Speeches, Letters, Lectures, and Translations—A Rejoinder to Bart Ehrman. Journal of Biblical Literature Vol. 136, No. 2 (Summer 2017), pp. 381-403 (23 pages). at. 389-390.

- ^ Jerome, Letter 120 [to Hedibia]: Therefore Titus served as an interpreter, as Saint Mark used to serve Saint Peter, with whom he wrote his Gospel. Also we see that the two epistles attributed to Saint Peter have different styles and turn phrases differently, by which it is discerned that it was sometimes necessary for him to use different interpreters.

- ^ Blum. "2 Peter" EBC, 12: 259.

- ^ Second Peter: Introduction, Argument, and Outline. Archive date: 9 December 2003. Access date: 19 August 2013.

- ^ Schreiner 2003, pp. 266.

- ^ Simon J. Kistemaker, New Testament Commentary: Exposition of the Epistles of Peter and the Epistle of Jude (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Pub Group, 1987), 224

- ^ Erhman, Bart (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. Harper Collins. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-06-182514-9.

Evidence comes in the final book of the New Testament to be written, 2 Peter, a book that most critical scholars believe was not actually written by Peter but by one of his followers, pseudonymously.

- ^ Moyise, Steve (9 December 2004). The Old Testament in the New. A&C Black. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-567-08199-5.

- ^ Stephen L. Harris (1992). Understanding the Bible. Mayfield. p. 388. ISBN 978-1-55934-083-0.

Most scholars believe that 1 Peter is pseudonymous (written anonymously in the name of a well-known figure) and was produced during postapostolic times.

- ^ Grant, Robert M. A Historical Introduction To The New Testament, chap. 14 Archived 2010-06-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Nongbri, "The Construction of P. Bodmer VIII and the Bodmer 'Composite' or 'Miscellaneous' Codex," 396

- ^ Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland (eds), Novum Testamentum Graece, 26th ed., (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1991), p. 689.

- ^ Gregory, Caspar René (1902). Textkritik des Neuen Testaments. Vol. 2. Leipzig: Hinrichs. p. 609. ISBN 1-4021-6347-9.

- ^ Callan 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Robinson 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Lapham, Fred (2004) [2003]. Peter: The Myth, the Man and the Writings: A study of the early Petrine tradition. T&T Clark International. pp. 149–171. ISBN 0567044904.

- ^ a b Donald Guthrie, Introduction to the New Testament 4th ed. (Leicester: Apollos, 1990), p. 806.

- ^ M. R. James, "The Second Epistle General of St. Peter and the General Epistle of St. Jude", in Cambridge Greek Testament (1912), p. xix; cf. Origen, Homily in Josh. 7.1.

- ^ Donald Guthrie, Introduction to the New Testament 4th ed. (Leicester: Apollos, 1990), p. 807.

- ^ Bigg 1901, 202–205.

- ^ J. W. C. Wand, The General Epistles of St. Peter and St. Jude (1934), p. 141.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 283–84.

- ^ Davids, P. H. (2004). “The Use of Second Temple Traditions in 1 and 2 Peter and Jude,” in Jacques Schlosser, ed. The Catholic Epistles and the Tradition, Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 176; Leuven: Peeters Publishers, 426–27.

- ^ Thiede, C. P. (1986). A Pagan Reader of 2 Peter: Cosmic Conflagration in 2 Peter 3 and the Octavius of Minucius Felix. Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 8(26), 79–96.

- ^ Osburn, D. Carroll. (2000). "Second Letter of Peter", in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, pp. 1039.

- ^ Elliott, John. (1993). "Second Epistle of Peter", in Anchor Bible Dictionary 5. pp. 282–87, at 287.

- ^ Elliott 1993, 283.

- ^ C. Detlef G. Müller (1992). "Apocalypse of Peter", in Schneemelcher, New Testament Apocrypha, vol. 2, pp. 620–38.

- ^ Bigg 1901, 207.

- ^ Spicq 1966, 189.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 162.

- ^ Helmbold, Andrew (1967). The Nag Hammati Gnostic Texts and the Bible. Grand Rapids, pp. 61.

- ^ Donald Guthrie, 1990, Introduction to the New Testament 4th ed. Leicester: Apollos, pp. 808–9, though the exception of the Syrian canon is noted, with acceptance occurring sometime before 509; cf. Jerome, De Viris Illustribus chapter 1.

- ^ "Table of Contents". ܟܬܒܐ ܩܕܝ̈ܫܐ: ܟܬܒܐ ܕܕܝܬܩܐ ܥܛܝܼܩܬܐ ܘ ܚ̇ܕܬܐ. [London]: United Bible Societies. 1979. OCLC 38847449.

- ^ Helmut Koester, 1982, Introduction to the New Testament, Vol. One: History, Culture and Religion of the Hellenistic Age, Fortress Press/Walter de Gruyter. pp. 107–10.

- ^ Reicke 1964, 146–47.

- ^ Kelly 1969, 228.

- ^ Aune, David E. (2003). The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 199

- ^ Köstenberger, Andreas J; Kellum, Scott L, and Quarles, Charles L. (2012). The Lion and the Lamb. B&H Publishing Group, pp. 338–39

- ^ Chaine 1939, 32–3.

- ^ Knoch 1990, 199.

- ^ Davids, Peter H. (2006). The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude. Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-80283726-4.

- ^ Werse 2016, 112.

- ^ Longenecker, Richard N. (2005). Contours of Christology in the New Testament, pp 280–81.

- ^ Werse 2016, 124.

- ^ a b T. Callan, "Use of the Letter of Jude by the Second Letter of Peter", Biblica 85 (2004), pp. 42–64.

- ^ The Westminster dictionary of New Testament and early Christian literature, David Edward Aune, p. 256

- ^ Christian-Jewish Relations Through the Centuries By Stanley E. Porter, Brook W. R. Pearson

- ^ Van Houwelingen 2010, 125.

- ^ Köstenberger 2020, 155.

- ^ Lévy L. B. (2019). "Ethics and Pseudepigraphy – Do the Ends Always Justify the Means?" Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts, pp. 335

- ^ a b Kuhn, Karl (2006). 2 Peter 3:1–13. Sage Publications (UK).

- ^ Koestenberger, AJ (2020). Handbook on Hebrews Through Revelation (Handbooks on the New Testament). Baker Academic, pp. 147.

- ^ Talbert, C. H. (1966) “II Peter and the delay of the parousia”, Vigiliae Christianae 20, 137–45.

- ^ Köstenberger, Kellum, Quarles, 2012. 862–63.

- ^ Callan, T. (2014). Use of the letter of Jude by the Second Letter of Peter. Bib 85, pp. 42–64.

- ^ Thurén, L. (2004). The Relationship between 2 Peter and Jude: A Classical Problem Resolved?. in The Catholic Epistles and the Tradition, ed. Jacques Schlosser. BETL 176, Leuven: Peeters, pp. 451–60.

- ^ Kasemann, Ernst (1982). Essays on New Testament Themes, "An Apologia for Primitive Christian Eschatology", trans. W. J. Montague, (SCM Press, 1968: Great Britain), pp. 172.

- ^ Bauckham 1983, 287.

- ^ a b Davids 2006, 260.

- ^ Kruger, M. J. (2020). 2 Peter 3:2, the Apostolate, and a Bi-Covenantal Canon. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 63, pp. 5–24.

- ^ Kruger 2020, 9–10.

- ^ Houwelingen 2010, 122. "These considerations make us think especially of Paul's letter to the Galatians. It is also possible to think of the letters to the Ephesians and Colossians – the latter is indeed difficult to interpret."

- ^ Levoratti, Armando J. (1981). La Biblia. Libro del Pueblo de Dios. Verbo Divino, 2018, pp. 1791. "In this passage is found the first mention of a collection of Paul's Letters considered an integral part of the canonical Scriptures. The passages therein which lent themselves to false interpretations were undoubtedly those concerning the second Coming of the Lord (1 Thess. 4. 13–5. 11; 2 Thess. 1.7–10; 2.1–12), and Christian liberty (Rom. 7; Gal. 5). In the latter, especially, some sought justification for moral licentiousness."

- ^ Kruger 2020, 15–20.

- ^ Kuhn 2006

- ^ Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1901). The Book of Psalms: with Introduction and Notes. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Vol. Book IV and V: Psalms XC-CL. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 839. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams, Thomas B, 1990. "A Commentary on the Second Epistle General of Second Peter" Soli Deo Gloria Ministries. ISBN 978-1-877611-24-7

- Callan, Terrance (2004). "Use of the Letter of Jude by the Second Letter of Peter". Biblica. 85: 42–64.

- Duff, Jeremy (2007). "78. 2 Peter". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1270–1274. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Green, Michael, 2007. "The Second Epistle of Peter and The Epistle of Jude: An Introduction and Commentary" Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8308-2997-2

- Leithart, Peter J, 2004. "The Promise of His Appearing: An Exposition of Second Peter" Canon Press. ISBN 978-1-59128-026-2

- Lillie, John, 1978. "Lectures on the First and Second Epistles of Peter" Klock & Klock. ISBN 978-0-86524-116-9

- Robinson, Alexandra (2017). Jude on the Attack: A Comparative Analysis of the Epistle of Jude, Jewish Judgement Oracles, and Greco-Roman Invective. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567678799.

- Seton, Bernard E, 1985. "Meet Pastor Peter: Studies in Peter's second epistle" Review & Herald. ISBN 978-0-8280-0290-5

External links

[edit]Online translations of the epistle

[edit]- Book of 2 Peter (NLT) at BibleGateway.com

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

Bible: 2 Peter public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: 2 Peter public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Other

[edit]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- BibleProject Animated Overview (Evangelical Perspective)