Biafra: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

|national_anthem = [[Land of the Rising Sun (national anthem)]] |

|national_anthem = [[Land of the Rising Sun (national anthem)]] |

||

|image_flag = Flag of Biafra.svg |

|image_flag = Flag of Biafra.svg |

||

|image_coat = Biafra coat of arms.png |

|||

|image_map = LocationBiafra.PNG |

|image_map = LocationBiafra.PNG |

||

|image_map_caption = Map of Biafra inside Nigeria |

|image_map_caption = Map of Biafra inside Nigeria |

||

Revision as of 15:39, 2 September 2008

Republic of Biafra | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967–1970 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Motto: Peace, Unity, Freedom | |||||||||

| Anthem: Land of the Rising Sun (national anthem) | |||||||||

Map of Biafra inside Nigeria | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||

| Capital | Enugu | ||||||||

| Common languages | English (official), Igbo (also Ibo), Efik/Annang/Ibibio, Ekoi, Ijaw | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

• Established | May 30 1967 | ||||||||

| January 15 1970 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1967 | 76,145.65 km2 (29,400.00 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1967 | 13,500,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Biafran pound | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Republic of Biafra was a secessionist state in south-eastern Nigeria. Biafra was inhabited mostly by the Igbo people (or Ibo[1]) and existed from 30 May 1967, to 15 January 1970. The secession was led by the Igbo due to economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions among the various peoples of Nigeria and the creation of the new country, named after the Bight of Biafra (the Atlantic bay to its south),[2] was among the complex causes for the Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Nigerian-Biafran War.

Biafra was recognized by Gabon, Haïti, Côte d'Ivoire, Tanzania and Zambia. Other nations did not give official recognition, but provided assistance to Biafra. Israel, France, Portugal, Rhodesia, South Africa and the Vatican City provided support.[3] Biafra also received aid from non-state actors; Joint Church Aid, Holy Ghost Fathers of Ireland, Caritas International, MarkPress and U.S. Catholic Relief Services all gave support.[3]

History

Secession

In 1960, Nigeria became independent of the United Kingdom.[4] Similar to the other new African states, the borders of the country were not drawn according to earlier territories. Hence, the northern desert region of the country contained semi-autonomous feudal Muslim states, while the southern population was predominantly Christian and animist. Furthermore, Nigeria's oil, its primary source of income, was located in the south of the country.[4]

Following independence, Nigeria was divided primarily along ethnic lines with Hausa and Fulani in the north, Yoruba in the south-west, and Igbo in the south-east.[4] In response to riots a year earlier, which had left roughly 30,000 Igbo dead and approximately a million Igbo refugees,[5] in January 1966, a group of primarily eastern Igbo led a military rebellion in order to secede from Nigeria proper.[6][7][8]

In July 1966 northern officers and army units staged a coup. Muslim officers named a Christian from a small ethnic group (the Anga) in central Nigeria, Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu "Jack" Gowon, as the head of the Federal Military Government (FMG). Continuing violence prevented a return to civilian rule; eight to ten thousand Igbo were killed in the north, and northerners were killed in eastern cities.[9]

Now, therefore, I, Lieutenant-Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, by virtue of the authority, and pursuant to the principles, recited above, do hereby solemnly proclaim that the territory and region known as and called Eastern Nigeria together with her continental shelf and territorial waters shall henceforth be an independent sovereign state of the name and title of "The Republic of Biafra".

In January 1967, the military leaders and senior police officials of each region met in Aburi, Ghana and agreed on a loose confederation of regions. The Northerners were at odds with the Aburi Accord; Obafemi Awolowo, the leader of the Western Region warned that if the Eastern Region seceded, the Western Region would also, which persuaded the northerners.[9]

The eastern government rejected the plan for reconciliation; on 26 May it voted to secede from Nigeria. On 30 May, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, the Eastern Region's military governor, announced the Republic of Biafra, citing the Easterners killed in the post-coup violence.[9][4] The large amount of oil in the region created conflict, as oil was a large component of the Nigerian economy.[11]

War

The FMG launched "police measures" to annex the Eastern Region. The FMG's initial efforts were unsuccessful; the Biafrans successfully launched their own offensive, taking land in the Mid-Western Region. By 1967, the FMG had regained the land, and by 1968, offensive measures by the FMG shrunk Biafra to one-tenth of its original size.[9][12]

In September 1968, the federal army planned what Gowon described as the "final offensive." Initially the final offensive was neutralized by Biafran troops. In the latter stages, a Southern FGM offensive managed to break through.[9]

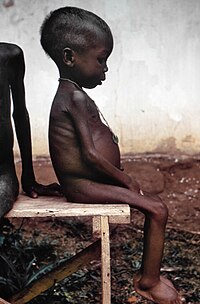

On June 30 1969, the Nigerian government banned all Red Cross aid to Biafra; two weeks later it allowed medical supplies through the front line, but restricted food supplies.[12] Later in October 1969, Ojukwu appealed to United Nations to mediate a cease-fire. The federal government called for Biafra's surrender. In December, the FGM managed to cut Biafra in half. Ojukwu fled to the Ivory Coast, leaving his chief of staff, Philip Effiong, to act as the "officer administering the government". Effiong called for an cease-fire January 12 and submitted to the FGM.[9] More than one million people had died in battle or from starvation.[5][13]

Geography

Enclosed in Biafra's borders was over 29,400 square miles of land;[14] the land borders were shared with Nigeria to the north and Cameroon to the east. Its coast lied on the Gulf of Guinea in the south.

The former country's southeast border Benue Hills and mountains that led to Cameroon. Two rivers flood from Biafra into the Gulf of Guinea: the Cross River and the Niger River.[15]

Climate

Biafra had a tropical climate with two distinct seasons: dry and rainy. From April to October the rainy season took place, with heavy rain and high humidity. The heaviest rain occurred between June and July with up to 360 mm (14 in) of rain level. The temperature of the region during a clear day is 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) high and 22 degrees Celsius (71.6 degrees Fahrenheit) low. The second season started in November and ended in April. It is a dry season with the lowest rain level 16 mm (0.63 in) in February. The temperature in the night reached 20 °C (68 °F) and in the day it had a peak temperature of 36 °C (96.8 °F).[16]

Language

The predominant language of Biafra was the Igbo language[17]. There are hundreds of different dialects and Igboid languages that the Igbo language is comprised of, such as Ikwerre and Ekpeye dialects.[18] Along with Igbo there were a variety of other different languages, including Ibibio, Ijaw and so on.

Economy

An early institution created by the Biafran government was the Bank of Biafra, accomplished under ‘Decree No. 3 of 1967'.[19] The bank carried out all central banking functions including the administration of foreign exchange and the management of the public debt of the Republic.[19] The bank was administered by a Governor and four Directors; the first governor, per the signature on bank notes, was Sylvester U. Uqoh.[19] A second decree, ‘Decree No.4 of 1967’, modified the Banking Act of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for the Republic of Biafra.[19]

The Bank was first located in Enugu, but, due to the ongoing war, the bank was relocated several times.[19] Biafra attempted to finance the war through foreign exchange. After Nigeria announced their currency would no longer be legal tender (to make way for a new currency), this effort increased; after the announcement, tons of Nigerian bank notes were transported in an effort to acquire foreign exchange. The currency of Biafra had been the Nigerian pound, until the Bank of Biafra started printing out its own notes, the Biafran pound.[19] The new currency went public on 28 January 1968, and the Nigerian pound was not accepted as an exchange unit.[19] The first issue of the bank notes included only 5 shillings notes and 1 pound notes. The bank of Nigeria exchanged only 30 pounds for an individual and 300 pounds for Enterprises in the second half of 1968.[19]

In 1969 new Notes were introduced: £10, £5, £1, 10/- and 5/-.[19]

It is estimated that a total of £115-140 million Biafran pounds were in circulation by the end of the conflict. This wasn't much as the Biafran population was 14 million making an estimate of 10£ per person.[19]

Military

At the beginning of the war Biafra had 3,000 troops, but at the end of the war the troops totaled 30,000.[20] There was no official support for the Biafran army by another Nation throughout the war. The Biafrans had at the beginning two B-25 Mitchells, one B-26 Marauder, and a a converted DC-3. Because of the lack of official support, the Biafrans manufactured their weapons locally. In 1968 the Swede pilot Carl Gustaf von Rosen suggested the project to general Ojukwu the Minicoin. By the spring of 1969, Biafra had built five MFI-9Bs in Gabon, calling them "Biafra Babies". They were coloured green, were able to carry six 68mm anti-armour rockets and had simple sights. The six airplanes were driven by three Swedish pilots and three Biafran pilots.

Legacy

The international humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières ("Doctors Without Borders") came out of the suffering in Biafra. During the crisis, French medical volunteers, in addition to Biafran health workers and hospitals, were subjected to attacks by the Nigerian army and witnessed civilians being murdered and starved by the blockading forces. French doctor Bernard Kouchner also witnessed these events, particularly the huge number of starving children, and, when he returned to France, he publicly criticised the Nigerian government and the Red Cross for their seemingly complicit behaviour. With the help of other French doctors, Kouchner put Biafra in the media spotlight and called for an international response to the situation. These doctors, led by Kouchner, concluded that a new aid organisation was needed that would ignore political/religious boundaries and prioritise the welfare of victims.[21]

In their book, Smallpox and its Eradication, Fenner and colleagues describe how vaccine supply shortages during the Biafra smallpox campaign led to the development of the focal vaccination technique, later adopted worldwide by the World Health Organization, which led to the early and cost effective interruption of smallpox transmission in west Africa and elsewhere.

On 29 May 2000, the Lagos Guardian newspaper reported that the now ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo commuted to retirement the dismissal of all military persons who fought for the breakaway state of Biafra during Nigeria's 1967-1970 civil war. In a national broadcast, he said the decision was based on the belief that "justice must at all times be tempered with mercy".[22]

Violence between Christians and Muslims (usually Igbo Christians and Hausa or Fulani Muslims) has been incessant since the end of the civil war in 1970.

In July 2006 the Center for World Indigenous Studies reported that government sanctioned killings were taking place in the southeastern city of Onitsha, because of a shoot-to-kill policy directed toward Biafran loyalists, particularly members of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB).[23][24]

Movement to re-secede

The "Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra" (MASSOB) advocates a separate country for the Igbo people of south-eastern Nigeria.[13] They accuse the state of marginalising the Igbo people. MASSOB says it is a peaceful group and advertises a 25-stage plan to achieve its goal peacefully.[25] The Nigerian government accuses MASSOB of violence; Massob's leader, Ralph Uwazuruike, was arrested in 2005 and is being detained on treason charges; MASOB is calling for his release. Massob is also championing the release of oil militant Mujahid Dokubo-Asari, who is facing similar charges.[13]

References

- ^ Biafra on Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites. McFarland & Company. p. 58. ISBN 0786422483.

- ^ a b Nowa Omoigui. "Federal Nigerian Army Blunders of the Nigerian Civil War - Part 2" (HTML). Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ a b c d Barnaby Philips (2000-01-13). "Biafra: Thirty years on" (HTML). The BBC.

- ^ a b James Brooke (1987-07-14). "Few Traces of the Civil War Linger in Biafra" (HTML). New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ Nowa Omoigui. "OPERATION 'AURE': The Northern Military Counter-Rebellion of July 1966" (HTML). Nigeria/Africa Masterweb.

- ^ Willy Bozimo. "Festus Samuel Okotie Eboh (1912 - 1966)" (HTML). Niger Delta Congress. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "1966 Coup: The last of the plotters dies". OnlineNigeria.com. 2007-03-20.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biafran Secession: Nigeria 1967-1970" (HTML). Armed Conflict Events Database. 2000-12-16.

- ^ "Ojukwu's Declaration of Biafra Speech" (HTML). Citizens for Nigeria. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ "ICE Case Studies" (HTML). American University. November 1997.

- ^ a b "On This Day (30 June)" (HTML). BBC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|langage=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Senan Murray (2007-05-03). "Reopening Nigeria's civil war wounds" (HTML). BBC. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ "Introducing the Republic of Biafra" (HTML). Government of the Republic of Biafra. Biafra Land.

- ^ "Nigeria". Britannica. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "Igbo insight guide to Enugu and Igboland's Culture and Language".

- ^ Ònyémà Nwázùé. "INTRODUCTION TO THE IGBO LANGUAGE". Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ "Igbo". Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Symes, Peter (1997). "The Bank Notes of Biafra" (HTML). International Bank Note Society Journal. 36 (4). Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ^ "Operation Biafra Babies". Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ Bortolotti, Dan (2004). Hope in Hell: Inside the World of Doctors Without Borders, Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55297-865-6.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Emerging Genocide in Nigeria

- ^ Chronicles of brutality in Nigeria 2000-2006

- ^ Estelle Shirbon (2006-07-12). "Dream of free Biafra revives in southeast Nigeria" (HTML). Reuters.

See also

- Land of the Rising Sun (national anthem)

- Auberon Waugh

- List of A-26 Invader operators

- Manillas

- Nigerian Civil War

- Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra

- Radio Northsea International

- Ambazonia

External links

- My Biafran Eyes - Writer Okey Ndibe's memoir of the Biafran War in Guernica

- These Women Are Brave - A project on Igbo women's experiences during the Biafran war.