Umpire (baseball): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 181: | Line 181: | ||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+ MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - UMPIRING CREWS 2014 <ref>{{cite|url=http://www.closecallsports.com/2014/03/ |

|+ MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL - UMPIRING CREWS 2014 <ref>{{cite|url=http://www.closecallsports.com/2014/03/roster-2014-mlb-umpire-crew-list.html|work=Close Call Sports|date=March 26, 2014|title=2014 MLB Umpire Crew List}}</ref> <!-- if required --> |

||

! Crew |

! Crew |

||

! Crew Chief |

! Crew Chief |

||

Revision as of 22:18, 7 April 2014

In baseball, the umpire is the person charged with officiating the game, including beginning and ending the game, enforcing the rules of the game and the grounds, making judgment calls on plays, and handling the disciplinary actions.[1] The term is often shortened to the colloquial form ump. They are also sometimes addressed as blue at lower levels due to the common color of the uniform worn by umpires. In professional baseball, the term "blue" is seldom used by players or managers, who instead call the umpire by name. Although games were often officiated by a sole umpire in the formative years of the sport, since the turn of the 20th century, officiating has been commonly divided among several umpires, who form the umpiring crew.

Duties and positions

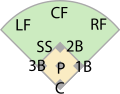

In a game officiated by two or more umpires, the umpire in chief (or home plate umpire) is the umpire who is in charge of the entire game. This umpire calls balls and strikes, calls fair balls and foul balls short of first/third base, and makes most calls concerning the batter or concerning baserunners near home plate.[1] If another umpire leaves the infield to cover a potential play in foul ground or in the outfield, then the plate umpire may move to cover a potential play near second or third base. (The umpire-in-chief should not be confused with the crew chief, who is often a different umpire; see below.) In the event that an umpire is injured and only three remain, the second base position will generally be left vacant.

In nearly all levels of organized baseball, including the majors, an umpiring crew rotates so that each umpire in the crew works each position, including plate umpire, an equal number of games. In the earliest days of baseball, however, many senior umpires always worked the plate, with Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem being the last umpire to do so. Klem did so for the first 16 years of his career.[2] On the Major League level, an umpiring crew generally rotates positions clockwise each game. For example, the plate umpire in one game would umpire third base in the next.

Other umpires are called base umpires and are commonly stationed near the bases. (Field umpire is a less-common term.) When two umpires are used, the second umpire is simply the base umpire. This umpire will make most calls concerning runners on the bases and nearby plays, as well as in the middle of the outfield. When three umpires are used, the second umpire is called the first-base umpire and the third umpire is called the third-base umpire, even though they may move to different positions on the field as the play demands.[1] These two umpires also call checked swings, if asked by the plate umpire (often requested by catcher or defensive manager; however, only the plate umpire can authorize an appeal to the base umpire): the first base umpire for right-handed batters, and the third base umpire for left-handed batters; to indicate a checked swing, the umpire will make a "safe" gesture with his arms. To indicate a full swing, he will clench his fist.

When four umpires are used (as is the case for all regular season MLB games), each umpire is named for the base at which he is stationed. Sometimes a league will provide six umpires; the extra two are stationed along the outfield foul lines are called the left-field and right-field umpires (or simply outfield umpires).

Outfield umpires are used in major events, such as the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, and depending on the level, at parts of post-season playoffs. For Major League Baseball, all playoff levels use six umpires, while at lower levels, six umpires are used at the championship games (such as NCAA).[3] Rulings on catches of batted balls are usually made by the umpire closest to the play.

Crew chief

The term umpire-in-chief is not to be confused with the crew chief, who is usually the most experienced umpire in a crew. At the major-league and high minor-league (Class AAA and AA) levels, the crew chief acts as a liaison between the league office and the crew and has a supervisory role over other members of the crew.[4]

For example, on the Major League level, "The Crew Chief shall coordinate and direct his crew's compliance with the Office of the Commissioner's rules and policies. Other Crew Chief responsibilities include: leading periodic discussions and reviews of situations, plays and rules with his crew; generally directing the work of the other umpires on the crew, with particular emphasis on uniformity in dealing with unique situations; assigning responsibilities for maintaining time limits during the game; ensuring the timely filing of all required crew reports for incidents such as ejections, brawls and protested games; and reporting to the Office of Commissioner any irregularity in field conditions at any ballpark."[4] Thus, on the professional level, some of the duties assigned to the umpire-in-chief (the plate umpire) in the Official Baseball Rules have been reassigned to the crew chief, regardless of the crew chief's umpiring position during a specific game.

Judgment calls

Unlike referees in American football, an umpire's judgment call is final, unless the umpire making the call chooses to ask his partner(s) for help and then decides to reverse it after the discussion.[1] If an umpire seems to make an error in rule interpretation, his call, in some leagues, can be officially protested.[1] If the umpire is persistent in his or her interpretation, the matter will be settled at a later time by a league official.

Since 28 August 2008, Major League Baseball (MLB) has inserted the possibility of reviewing close calls on balls hit near the foul poles and the outfield fence, to decide whether a ball hit is fair/foul or to see if it hit the wall or if it hit the yellow line to make it a home run.[5] Since umpires are often more than 200 feet (61 m) away from the foul poles or the outfield fence while making a call, MLB saw instant replay as an appropriate way of helping umpires make correct calls on outfield balls. "I believe that the extraordinary technology that we now have merits the use of instant replay on a very limited basis", MLB Commissioner Bud Selig said. "The system we have in place will ensure that the proper call is made on home run balls and will not cause a significant delay to the game."[5] It was first used on 3 September 2008, when New York Yankees third baseman Alex Rodriguez hit a deep fly ball off Tampa Bay Rays pitcher Troy Percival right over the left field foul pole at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida.[6] Coincidentally, the first official use of instant replay during the postseason came on a home run by Rodriguez in Game 3 of the 2009 World Series. Replay was used to confirm that a to deep right field was a home run despite rebounding into the park. The ball was initially called a double, but replay showed the ball had hit the lens of a TV camera that stuck out just above the wall. As part of the new collective bargaining agreement signed in 2011, replay can be expanded (with the approval of the umpires' union) to include fair/foul calls and whether a line drive or fly ball was trapped or caught.[7]

In the early years of professional baseball, umpires were not engaged by the league but rather by agreement between the team captains. However, by the start of the modern era in 1901, this had become a league responsibility. There is now a unitary major league umpiring roster, although until the 1999 labour dispute that led to the decertification of the Major League Umpires Association, there were separate National and American League umpires. As a result of the 2000 collective bargaining agreement between Major League Baseball and the newly formed World Umpires Association, all umpires were placed on one roster and can work in either league.

Amateur umpiring

An amateur umpire officiates non-professional or semi-professional baseball. Many amateur umpires are paid (typically on a per-game basis) and thus might be considered professionals, while some amateur umpires are unpaid.[citation needed] According to the Little League official website, umpires should be volunteers.[8]

There are numerous organizations that test or train anyone interested in umpiring for local leagues, and can help make connections to the leagues in the area. Little League and the Babe Ruth League are two of the most popular organizations when it comes to youth baseball, and each have their own application, test, and training process for becoming an umpire. In Canada, many municipalities run their own amateur baseball leagues for children and hire umpires through an umpire-in-chief.

For the Little League World Series, amateur umpires from around the world participate on a volunteer basis. Prospective Little League World Series umpires must participate at various levels of Little League All-Star tournaments, ranging from district to state to regional tournaments, prior to being accepted to work the World Series tournament.[9]

High school umpiring

High School umpires are part-time umpires. These umpires also have jobs. A high school umpire has to go to clinics and rules meetings before becoming an umpire. A person trying to become a high school umpire has to register with their respective state.[10] When they register with the state they receive a rulebook, a casebook and an umpire manual. After reading through the rulebooks the umpires meet at clinics and rules meetings to discuss rules and mechanics. Clinics and rules meetings are crucial in an umpire’s development. Once an umpire has gone to clinics and rules meetings they then start to umpire scrimmages. In a scrimmage an umpire gets hands on training for the first time. Scrimmages are where young umpires can learn from veteran umpires. After going to clinics and umpiring in scrimmages the umpire then has to take a rule exam. The umpire must past the exam in order to umpire during the season.[11] Once the umpire has passed the exam he/she is now ready to umpire high school level ballgames.

High School umpires are paid per game and the rate differs from state to state. The plate umpire and base umpire are paid the same amount for each game. Umpires in high school games use a two-man crew.[12] Three-man and four-man crews are used in later rounds of the playoffs.

Umpire training and career development

Becoming a Major League Baseball umpire requires rigorous training, and very few succeed. Provided the individual makes satisfactory progress throughout, it typically takes from 7–10 years to achieve MLB status. First, a person desiring to become a professional umpire must attend one of two private umpiring schools authorized by Major League Baseball: The Umpire School at Vero Beach or The Harry Wendelstedt Umpire School.[13] Both schools are run by former Major League umpires and are located in Florida. There are no prerequisites for attending these schools; however, there is an Umpire Camp, run by Major League Baseball, that is generally considered a "tool for success" at either of these schools. These camps, offered as two separate one-week sessions, are held in November in Southern California. Top students at these camps are eligible to earn scholarships to either of the professional umpire schools in Florida.[14]

After five weeks of training, each school sends its top students to the Professional Baseball Umpires Corporation (PBUC) evaluation course also held in Florida.[15] The actual number of students sent on to the evaluation course is determined by PBUC with input from the umpire schools.[15] Generally, the top 10 to 20 percent of each school's graduating class will advance to the evaluation course. The evaluation course is conducted by PBUC staff, which differs in personnel from the staff at the respective umpire schools.[15] The evaluation course generally lasts around 10 days. Depending on the number of available positions in the various minor leagues, some (but not all) of the evaluation course attendees will be assigned to a low level minor league. Out of approximately 300 original umpire school students, about 30-35 will ultimately be offered jobs in Minor League Baseball after the evaluation course.

Professional umpires begin their careers in one of the Rookie or Class "A" Short-Season leagues, with Class-A being divided into three levels (Short-Season, Long-Season and Advanced "A").[15] Top umpiring prospects will often begin their careers in a short-season "A" league (for example, the New York – Penn League), but most will begin in a rookie league (for example, the Gulf Coast League).

Throughout the season, all minor league umpires in Rookie leagues, Class-A, and Class-AA are evaluated by members of the PBUC staff.[16] All umpires receive a detailed written evaluation of their performance after every season.[16] In addition, all umpires (except those in the rookie or Short Season Class-A leagues) receive written mid-season evaluations.[16]

Generally, an umpire is regarded as making adequate progress "up the ranks" if he advances up one level of Class "A" ball each year (thus earning promotion to Class AA after three to four years) and promotion to Class AAA after two to three years on the Class AA level. However, this is a very rough estimate and other factors not discussed (such as the number of retirements at higher levels) may dramatically affect these estimates. For example, many umpires saw rapid advancement in 1999 due to the mass resignation of many Major League umpires as a collective bargaining ploy.

When promoted to the Class AAA level, an umpire's evaluation will also be conducted by the umpiring supervisory staff of Major League Baseball. In recent years, top AAA prospects, in addition to umpiring and being evaluated during the regular season (in either the International or Pacific Coast League), have been required to umpire in the Arizona Fall League where they receive extensive training and evaluation by Major League Baseball staff.

In addition, top AAA prospects may also be rewarded with umpiring only Major League preseason games during spring training (in lieu of Class AAA games). Additionally, the very top prospects may umpire Major League regular season games on a limited basis as "fill-in" umpires (where the Class AAA umpire replaces a sick, injured or vacationing Major League umpire).

Finally, upon the retirement (or firing) of a Major League umpire, a top Class AAA umpire will be promoted to Major League Baseball's permanent umpire staff. During this entire process, if an umpire is evaluated as no longer being a major-league prospect, he will be released, ending his professional career. In all, PBUC estimates that it will take an umpire seven to eight years of professional umpiring before he will be considered for a major league position.[15]

There are currently 70 umpires on Major League Baseball's permanent staff, and 22 Class AAA umpires eligible to umpire regular season Major League games as a "fill-in" umpire.[17]

Major league umpires earn $100,000 to $300,000 per year depending on their experience, with a $357 per diem for hotel and meals.[18] Minor league umpires earn between $1,800 to $3,400 per month during the season. The exact amount is based on the umpire's classification and experience.[19]

Famous umpires

Hall of Fame

The following ten umpires have been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame:

- Al Barlick (NL, 1940–1943, 1946–1955, 1958–1971)(Class of 1989)

- Nestor Chylak (AL, 1954–1978)(Class of 1999)

- Jocko Conlan (NL 1941-1964)(Class of 1974)

- Tommy Connolly (NL, 1898–1900; AL, 1901–1931)(Class of 1953)

- Billy Evans (AL, 1906–1927)(Class of 1973)

- Doug Harvey (NL 1962-1992)(Class of 2010)

- Cal Hubbard (AL, 1936–1951)(Class of 1976)

- Bill Klem (NL 1905-1941)(Class of 1953)

- Bill McGowan (AL, 1925–1954)(Class of 1992)

- Hank O'Day (NL, 1895, 1897-1911, 1913, 1915-1927)(Class of 2013)

Numbers retired by the National and American Leagues

Like players, umpires are identified by numbers on their uniforms. National League umpires began wearing numbers in 1970 (though they were assigned numbers in the 1960s) and American League umpires were assigned and began wearing uniform numbers in 1980. The National League umpires' numbers were initially assigned in alphabetical order (Al Barlick wearing number 1, Ken Burkhart number 2, etc.) from 1970 to 1978, which meant that an umpire's number could change each year depending on retirements and other staff changes. In 1979, the National League changed the numbering system and thereafter a number's umpire did not change from year to year. At first, as new umpires, they would be assigned higher numbers (for example, in 1979, Dave Pallone, Steve Fields, Fred Brocklander, and Lanny Harris were assigned numbers 26 to 29 instead of available numbers between 1 and 25). The National League numbering practice changed again in the mid-1980s, when new umpires were assigned previously used numbers (for example, in 1982 Gerry Davis was assigned number 12, previously worn by Andy Olsen, and in 1985 Tom Hallion was assigned number 20, previously worn by Ed Vargo.)

The American League's number assignments were largely random. Bill Haller, the senior American League umpire in 1980, wore number 1 until his retirement following the 1982 World Series, but the number was never reassigned.

In 2000, the American League and National League umpiring staffs were merged into a unified staff under the auspices of Major League Baseball, and all numbers were made available, including the numbers that had been retired by one of the leagues. (For example, the American League had retired Lou DiMuro's number 16 after his death, but it was made available to his son Mike after the staffs were unified.) In the event of duplications, the more senior umpire was given the first choice. (For example, Al Clark in the AL and Jerry Layne in the NL both wore the number 24, but because Clark had more seniority he was assigned 24 and Layne number 26. When Clark was relieved of his duties in 2000, Layne was able to obtain number 24.)

From time to time, Major League Baseball retires those numbers for umpires who have given outstanding service to the game, or in honor of umpires who have died.[20]

Since unified umpiring crews were established in 2000, all numbers are available to a Major League Baseball umpire, as each retired number was reserved per league. No umpire numbers have been retired since the current format was established.

- #1 Bill Klem (NL, 1905–41); currently worn by Bruce Dreckman

- #2 Nick Bremigan (AL, 1974–89); currently worn by Dan Bellino

- #2 Jocko Conlan (NL, 1941–64); worn by Jerry Crawford during his tenure in the NL (1977-1999)

- #3 Al Barlick (NL, 1940–43, 1946–55, 1958–71); currently worn by Tim Welke

- #9 Bill Kunkel (AL, 1968–84); also an NBA referee. Currently worn by Brian Gorman.

- #10 John McSherry (NL, 1971–1996); died at home plate during the Cincinnati Reds-Montreal Expos season opener. Currently worn by Phil Cuzzi.

- #16 – Lou DiMuro (AL, 1963–82); killed in an auto-related accident after a game in Arlington, Texas. Currently worn by DiMuro's son Mike.

- #42 – Jackie Robinson (retired through all of Major League Baseball since April 15, 1997.) Worn by Fieldin Culbreth in the American League through 1999; Culbreth switched to #25 when a unified umpiring staff was first used in 2000.

Longest major league careers

Most games

- 5,368 - Bill Klem

- 5,159 - Bruce Froemming

- 4,768 - Tommy Connolly

- 4,670 - Doug Harvey

- 4,559 - Joe West

(through end of 2013 season)

Most seasons

Careers beginning prior to 1920:

- 37 - Bill Klem (NL, 1905–41)

- 35 - Bob Emslie (AA, 1890; NL, 1891–1924)

- 34 - Tommy Connolly (NL, 1898–1900; AL, 1901–31)

- 30 - Hank O'Day (NL, 1895, 1897–1911, 1913, 1915–27)

- 29 - Bill Dinneen (AL, 1909–37)

- 29 - Cy Rigler (NL, 1906–22, 1924–35)

- 25 - Brick Owens (NL, 1908, 1912–13; AL, 1916–37)

- 25 - Ernie Quigley (NL, 1913–37)

Careers beginning from 1920 to 1960:

- 30 - Bill McGowan (AL, 1925–54)

- 28 - Al Barlick (NL, 1940–43, 1946–55, 1958–71)

- 27 - Bill Summers (AL, 1933–59)

- 26 - Tom Gorman (NL, 1951–76)

- 25 - Nestor Chylak (AL, 1954–78)

- 25 - Jim Honochick (AL, 1949–73)

Careers beginning since 1960:

- 37 - Bruce Froemming (NL, 1971–99; MLB, 2000–07) Froemming is recognized by MLB as having the longest tenure of any umpire in MLB history in terms of number of seasons umpired.[21]

- 36 - Joe West (NL, 1976–99; MLB 2002–present), senior Major League umpire as of 2014

- 35 - Jerry Crawford (NL, 1976–99; MLB, 2000–2010), son of NL umpire Shag Crawford (1951-76) and brother of NBA official Joey Crawford

- 35 - Joe Brinkman (AL, 1972–99; MLB, 2000–06) last active umpire to have used the balloon chest protector (Brinkman switched to the inside protector in 1980); former owner of umpire school; last active AL umpire to work prior to implementation of DH.

- 33 - Ed Montague (NL, 1974, 1976–99; MLB, 2000–09) One of three umpires (Bill Klem and Bill Summers were the others) to serve as World Series crew chief four times

- 33 - Harry Wendelstedt (NL, 1966–98) The Wendelstedt family operates one of two MLB-approved umpire schools; son Hunter, currently an MLB umpire, took over after Harry's death in 2012.

- 33 - Derryl Cousins (AL 1979-99; MLB 2000–2012) last remaining replacement called up during the 1979 umpire strike and last AL umpire to have worn the red blazer (1973–79)

- 32 - Dave Phillips (AL, 1971-1999; MLB, 2000-2002) He was the crew chief during the 1979 Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park, ordering the Chicago White Sox to forfeit the second game of a scheduled doubleheader to the visiting Detroit Tigers. First umpire to throw Gaylord Perry out of a game for an illegal pitch (1982), threw out Albert Belle for a corked bat (1994)

- 32 - Larry Barnett (AL, 1968–99) Made "no interference" call in Game 3 of the 1975 World Series

- 32 - Tim McClelland (AL, 1983-99, MLB 2000-present), home plate umpire in Pine Tar Game

- 31 - Doug Harvey (NL, 1962–92), home plate umpire in Game 1 of 1988 World Series, punctuated by dramatic pinch-hit home run by an injured Kirk Gibson

- 30 - Gerry Davis (NL, 1982-1999, MLB 2000-present), owner of officials equipment store

- 30 - John Hirschbeck (AL, 1984-99, MLB 2000-present), involved in infamous "spitting" incident with Roberto Alomar

- 30 - Dana DeMuth (NL, 1985-99, MLB 2000-present), made (with Jim Joyce) controversial obstruction call in Game 3 of the 2013 World Series

- 30 - Tim Welke (AL 1985-99, MLB 2000-present), ejected Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox from Game 6 of the 1996 World Series, the last manager ejected in a World Series game

Others

Other noteworthy umpires have included:

- Emmett Ashford (AL, 1966–70), first black umpire in Major League Baseball; retired after working 1970 World Series

- Ted Barrett (MLB, 1999–present), first umpire to work home plate for two perfect games[22]

- Fred Brocklander (NL, 1979–92), called Game 6 of the 1986 National League Championship Series

- Amanda Clement (SD, 1904–1910), first paid female umpire

- Ria Cortesio (became first female umpire to work Futures Game in 2006; worked a spring training game in 2007)

- Don Denkinger (AL, 1969–98), made infamous call in Game 6 of the 1985 World Series, then ejected St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog and Cardinal pitcher Joaquín Andújar in Game 7

- Bill Dinneen (AL, 1909–37), called five no-hitters, and also pitched a no hitter (September 27, 1905); the only man to both pitch and call no-hit baseball games [23]

- Augie Donatelli (NL, 1950–73), made controversial "phantom tag" call in Game 2 of the 1973 World Series on the New York Mets' Bud Harrelson while sprawled on the ground at home plate

- Jim Evans (AL, 1971–99), ran one of only two official umpire schools until decertified after an incident on 2/16/2012

- John Gaffney (NL, 1884–86, 1891–94, 1899–1900; AA, 1888–89; PL, 1890)

- Bernice Gera (NAPBL, 1972-72), first female umpire in professional baseball

- Bill Haller (AL, 1963-82), brother of Major League catcher Tom Haller

- Tim Hurst (NL, 1891–97, 1900, 1903; AL, 1905–1909)

- Jim Joyce (AL, 1987–99; MLB, 2000–), umpire whose incorrect call led to Armando Galarraga's near-perfect game

- Bill Kunkel (AL, 1968–84) former Major League pitcher and NBA official; son Jeff was Major League infielder

- Ron Luciano (AL, 1969–80) All-American linemen for Syracuse University football team in late 1950s; wrote four books

- John McSherry (NL, 1971–96) Died of heart attack after seven pitches of 1996 season opener between Expos and Reds

- Jerry Neudecker (AL, 1966–85) Last AL umpire to use outside chest protector after league disallowed its use by new umpires starting in 1977

- Jake O'Donnell (AL, 1968–71) also an NBA official from 1967–95; only person to officiate both MLB and NBA all-star games

- Silk O'Loughlin (AL, 1902–18)

- Steve Palermo (AL, 1977–1991) career ended when he suffered spinal cord damage from a gunshot wound suffered on Dallas' Central Expressway while apprehending two armed robbers

- Pam Postema (1988, first female umpire to work an MLB spring training game, also worked the Hall of Fame Game in the same season)

- Beans Reardon (NL, 1926–49)

- Brian Runge (NL 1999, MLB 2000–2012), first third generation umpire following father Paul Runge (NL, 1974–97) and grandfather Ed Runge (AL, 1954–70)

- Jack Sheridan (PL, 1890; NL, 1892, 1896–97; AL, 1901–14)

- Art Williams (NL, 1972–77), first African-American umpire in the National League, worked the 1975 National League Championship Series

- Charlie Williams (NL, 1978–99, MLB 2000), in 1993, became first African-American umpire to work home plate in a World Series game

2014 umpiring crews

These are the crews of umpires for the 2014 MLB season. Crews frequently change over the course of the year as umpires are sometimes detached from their crew (so they do not work in their home city with some exceptions, such as the opening of a new stadium), are on vacation, or are injured.

a) Acting crew chief for 36 Tim McClelland (DL)

b) Acting crew chief for 37 Gary Darling (DL)

Other umpires on the DL include 11 Tony Randazzo, 34 Sam Holbrook

Origin of the word "umpire"

According to the Middle English dictionary entry for noumpere, the predecessor of umpire came from the Old French nonper (from non, "not" and per, "equal"), meaning "one who is requested to act as arbiter of a dispute between two people", or that the arbiter is not paired with anyone in the dispute.

In Middle English, the earliest form of this shows up as noumper around 1350, and the earliest version without the n shows up as owmpere, a variant spelling in Middle English, circa 1440.

The n was lost after it was written (in 1426–1427) as a noounpier with the a being the indefinite article. The leading n became attached to the article, changing it to an Oumper around 1475; this sort of linguistic shift is called juncture loss. Thus today one says "an umpire" instead of "a numpire".

The word was applied to the officials of many sports other than baseball, including association football (where it has been superseded by referee) and cricket (which still uses it).

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e "Official Rules: 9.00 The Umpire". MLB. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ Haudricourt, Tom (2007-04-14). "Chief among game's umpires". Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ "Special Event selection". MLB. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ a b "2007 MLB Umpire Crews". MLB. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ a b "MLB Press Release about the start of limited use of instant replay". MLB. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "First use of instant replay in MLB, Sept. 3 2008 at Tropicana Field, St. Petersburg". MLB. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "New in MLB labor deal -- more replay, longer All-Star Break". ESPN. Retrieved 2011-12-29.

- ^ Umpire's Role

- ^ "Umpires Home". Little League. Archived from the original on 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ [1], retrieved November 1, 2013

- ^ [2], retrieved November 1,2013

- ^ [3], retrieved November 1, 2013

- ^ "Where are the Professional Umpire Schools Located?". MiLB. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ MLB Umpire Camps | MLB.com: MLBUC

- ^ a b c d e Become an Umpire | MiLB.com Official Info | The Official Site of Minor League Baseball

- ^ a b c Umpires | MiLB.com Official Info | The Official Site of Minor League Baseball

- ^ Umpires: Roster | MLB.com: Official info

- ^ http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20070327/ap_on_sp_ba_ne/bbo_female_umpire_exhibition_game_3

- ^ Umpire Salaries | MiLB.com Official Info | The Official Site of Minor League Baseball

- ^ Umpires: Feature | MLB.com: Official info

- ^ Froemming now longest-tenured umpire | MLB.com: News

- ^ "Record Breaker: Another Perfecto, Umpiring History Made". Close Call Sports. June 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Umpires: Feature | MLB.com: Official info

- ^ "2014 MLB Umpire Crew List", Close Call Sports, March 26, 2014

Further reading

- Ruling Over Monarchs, Giants & Stars: Umpiring in the Negro Leagues & Beyond, by Bob Motley. First-hand account of umpiring in the dying days of Negro league ball. ISBN 1-59670-236-2. See: Negro league baseball#Further reading.

External links

- Umpires (including poems, quotations, rules, Hall of Famers, burial places). Baseball-Almanac

- Umpire (including several books, under "Further Reading"). Baseball-Reference.com

- Amateur Baseball Umpires Association

- Association of Minor League Umpires

- California Baseball Umpires Association, San Gabriel Valley Unit

- Copper State Umpires (including Arizona Umpire School)

- Umpire's Role. Little League Baseball & Softball

- Umpire Ejection Fantasy League. Close Call Sports

- MLB Umpires. Major League Baseball

- World Umpires Association (labor union for major-league umpires)

- A history of major league umpiring - by Larry R. Gerlach

- http://www.exploratorium.edu/baseball/clement.html (Amanda Clement bio page)