Harun al-Rashid: Difference between revisions

fixed transliteration |

m Anthony Appleyard moved page Harun al-Rashid to Harun ar-Rashid: Requested at WP:RM as uncontroversial (permalink) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 21:33, 18 May 2014

| Harun ar-Rashid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Harun ar-Rashid receiving a delegation sent by Charlemagne at his court | |||||

| 5th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate Abbasid Caliph in Ar-Raqqah | |||||

| Reign | 14 September 786 – 24 March 809 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Hadi | ||||

| Successor | al-Amin | ||||

| Born | 17 March 763 Rey, Iran | ||||

| Died | 24 March 809 (aged 46) Tus, Iran | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Zubaidah | ||||

| Issue | Muhammad, Caliph al-Amin Abdullah, Caliph al-Ma'mun Abbas, Caliph al-Mu'tasim Qasim Abdan Sukaynah | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | al-Mahdi | ||||

| Mother | al-Khayzuran | ||||

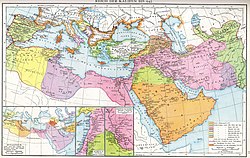

Harun ar-Rashid (Arabic: هارون الرشيد}; Hārūn ar-Rashīd) (17 March 763 or February 766 — 24 March 809) was the fifth Abbasid Caliph. His rule encompassed modern Iraq. His actual birth date is debatable, and various sources give dates from 763 to 766. His surname translates to "the Just," "the Upright" or "the Rightly-Guided"

Ar-Rashid ruled from 786 to 809, and his time was marked by scientific, cultural, and religious prosperity. Islamic art and Islamic music also flourished significantly during his reign. He established the legendary library Bayt al-Hikma ("House of Wisdom").[1]

Since Harun was intellectually, politically, and militarily resourceful, his life and his court have been the subject of many tales. Some are claimed to be factual, but most are believed to be fictitious. An example of what is factual, is the story of the clock that was among various presents that Harun had sent to Charlemagne. The presents were carried by the returning Frankish mission that came to offer Harun friendship in 799. Charlemagne and his retinue deemed the clock to be a conjuration for the sounds it emanated and the tricks it displayed every time an hour ticked.[2]

Among what is known to be fictional is The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, which contains many stories that are fantasized by Harun's magnificent court and even Harun ar-Rashid himself.[3]

The family of Barmakids which played a deciding role in establishing the Abbasid Caliphate declined gradually during his rule.

Amongst Shia Muslims he is despised for his role in the murder of the 7th Imam, Musa ibn Ja'far.

His life

Hārūn was born in Rey. He was the son of al-Mahdi, the third Abbasid caliph (ruled 775 – 785), and al-Khayzuran, a former slave girl from Yemen, and a woman of strong personality who greatly influenced affairs of state in the reigns of her husband and sons.

Hārūn was strongly influenced by the will of his mother in the governance of the empire until her death in 789. His vizier (chief minister) Yahya the Barmakid, Yahya's sons (especially Ja'far ibn Yahya), and other Barmakids generally controlled the administration.

The Barmakids were a Persian family (from Balkh) which dated back to the Barmak of Magi, who had become very powerful under al-Mahdi. Yahya had helped Hārūn in obtaining the caliphate, and he and his sons were in high favor until 798, when the caliph threw them in prison and confiscated their land. Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari dates this in 803 and lists various accounts for the cause: Yahya's entering the Caliph's presence without permission, Yahya's opposition to Muhammad ibn al Layth who later gained Harun's favour, Ja'far release of Yahya ibn Abdallah ibn Hasan whom Harun had imprisoned.

The fall of the Barmakids is far more likely due to their behaving in a manner that Harun found disrespectful (such as entering his court unannounced) and making decisions in matters of state without first consulting him. Al-Fadl ibn al-Rabi succeeded Yahya the Barmakid as Harun's chief minister.

Hārūn became caliph when he was in his early twenties. Before that, in 780 and again in 782, he had already nominally led campaigns against the Caliphate's traditional enemy, the Byzantine Empire. The latter expedition was a huge undertaking, and even reached the Asian suburbs of Constantinople. On the day of accession, his son al-Ma'mun was born, and al-Amin some little time later: the latter was the son of Zubaida, a granddaughter of al-Mansur (founder of the city of Baghdad); so he took precedence over the former, whose mother was a Persian. He began his reign by appointing very able ministers, who carried on the work of the government so well that they greatly improved the condition of the people.[4]

It was under Hārūn ar-Rashīd that Baghdad flourished into the most splendid city of its period. Tribute was paid by many rulers to the caliph, and these funds were used on architecture, the arts and a luxurious life at court.

In 796, Hārūn decided to move his court and the government to Ar Raqqah at the middle Euphrates. Here he spent 12 years, most of his reign. Only once did he return to Baghdad for a short visit. Several reasons might have influenced the decision to move to ar-Raqqa. It was close to the Byzantine border. The communication lines via the Euphrates to Baghdad and via the Balikh river to the north and via Palmyra to Damascus were excellent. The agriculture was flourishing to support the new Imperial center. And from Raqqa any rebellion in Syria and the middle Euphrates area could be controlled. Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani pictures in his anthology of poems the splendid life in his court. In ar-Raqqah the Barmekids managed the fate of the empire, and there both heirs, al-Amin and al-Ma'mun grew up.

Due to the Thousand-and-One Nights tales, Harun ar-Rashid turned into a legendary figure obscuring his true historic personality. In fact, his reign initiated the political disintegration of the Abbasid caliphate. Syria was inhabited by tribes with Umayyad sympathies and remained the bitter enemy of the Abbasids, while Egypt witnessed uprisings against Abbasids due to maladministration and arbitrary taxation. The Umayyads had been established in Spain in 755, the Idrisids in Morocco in 788, and the Aghlabids in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia) in 800. Besides, unrest flared up in Yemen, and the Kharijites rose in rebellion in Daylam, Kerman, Fars and Sistan. Revolts also broke out in Khorasan, and ar-Rashid waged many campaigns against the Byzantines.

For the administration of the whole empire, he fell back on his mentor and longtime associate Yahya bin Khalid bin Barmak. Rashid appointed him as his vizier with full executive powers, and, for seventeen years, this man Yahya and his sons, served Rashid faithfully in whatever assignment he entrusted to them.[5]

Ar-Rashid appointed Ali bin Isa bin Mahan as the governor of Khorasan. He tried to bring to heel the princes and chieftains of the region, and to reimpose the full authority of the central government on them. This new policy met with fierce resistance and provoked numerous uprisings in the region. A major revolt led by Rafi ibn al-Layth was started in Samarqand which forced Harun ar-Rashid to move to Khorasan. He first removed and arrested Ali bin Isa bin Mahan but the revolt continued unchecked. Harun ar-Rashid died very soon when he reached Sanabad village in Tus and was buried in the nearby summer palace of Humayd ibn Qahtaba, the former Abbasid governor in Khorasan.

Ar-Rashid virtually dismembered the empire by apportioning it between his two sons al-Amin and al-Ma'mun (with his third son, al-Qasim, being belatedly added after them). Very soon it became clear that by dividing the empire, Rashid had actually helped to set the opposing parties against one another, and had provided them with sufficient resources to become independent of each other.[citation needed] After the death of Harun ar-Rashid, civil war broke out in the empire between his two sons, al-Amin and al-Ma'mun, which spiralled into a prolonged period of turmoil and warfare throughout the Caliphate, ending only with Ma'mun's final triumph in 827.

Both Einhard and Notker the Stammerer refer to envoys travelling between Harun's and Charlemagne's courts, amicable discussions concerning Christian access to the Holy Land and the exchange of gifts. Notker mentions Charlemagne sent Harun Spanish horses, colourful Frisian cloaks and impressive hunting dogs. In 802 Harun sent Charlemagne a present consisting of silks, brass candelabra, perfume, balsam, ivory chessmen, a colossal tent with many-colored curtains, an elephant named Abul-Abbas, and a water clock that marked the hours by dropping bronze balls into a bowl, as mechanical knights—one for each hour—emerged from little doors which shut behind them. The presents were unprecedented in Western Europe and may have influenced Carolingian art.

When the Byzantine empress Irene was deposed, Nikephoros I became emperor and refused to pay tribute to Harun, saying that Irene should have been receiving the tribute the whole time. News of this angered Harun, who wrote a message on the back of the Roman emperor's letter and said "In the name of God the most merciful, From Amir al-Mu'minin Harun ar-Rashid, commander of the faithful, to Nikephoros, dog of the Romans. Thou shalt not hear, thou shalt behold my reply". After campaigns in Asia Minor, Nikephoros was forced to conclude a treaty, with humiliating terms.[6][7]

Harun made the pilgrimage to Mecca several times, e.g., 793, 795, 797, 802 and last in 803. Tabari concludes his account of Harun's reign with these words: "It has been said that when Harun ar-Rashid died, there were nine hundred million odd (dirhams) in the state treasury."

Ar-Rashid sent embassies to the Chinese Tang dynasty and established good relations with them.[8][9] He was called "A-lun" in the Chinese T'ang Annals.[10]

In 807 Caliph Harun ar-Rashid issued a decree that Jews wear a yellow belt and that Christians wear a blue belt.[11]

In 808, Harun went to settle the insurrection of Rafi ibn al-Layth in Transoxania, became ill, and died in 809. He was buried under the palace of Hamid ibn Qahtabi, the governor of Khurasan. The location later became known as Mashhad ("The Place of Martyrdom") because of the martyrdom of Imam ar-Ridha in 818. Another tradition maintains that the tomb of Harun was razed in the Mongol raids of 1220, by forces under the command of Genghis Khan.

Anecdotes

Many anecdotes attached themselves to the person of Harun ar-Rashid in the centuries following his rule. Saadi of Shiraz inserted a number of them into his Gulistan, in one telling how Harun enjoined his son to forgiveness.

Al-Masudi relates a number of interesting anecdotes in The Meadows of Gold illuminating the character of this caliph. For example, he recounts Harun's delight when his horse came in first, closely followed by al-Ma'mun's, at a race Harun held at Raqqa. Al-Masudi tells the story of Harun setting his poets a challenging task. When others failed to please him, Miskin of Medina succeeded superbly well. The poet then launched into a moving account of how much it had cost him to learn that song. Harun laughed saying he knew not which was more entertaining, the song or the story. He rewarded the poet.[12]

There is also the tale of Harun asking Ishaq ibn Ibrahim to keep singing. The musician did until the caliph fell asleep. Then, strangely, a handsome young man appeared, snatched the musician's lute, sang a very moving piece (al-Masudi quotes it), and left. On awakening and being informed of this, Harun said Ishaq ibn Ibrahim had received a supernatural visitation.

Harun, like a number of caliphs, is given an anecdote connecting a poem with his death. Shortly before he died, he is said to have been reading some lines by Abu al-Atahiya about the transitory nature of the power and pleasures of this world.

Popular culture and references

- Rex Stout's The League of Frightened Men, (1935) page 191, has Mr. Hibbard say, "[Harun-al-Rashid] was seeking entertainment [not life]."

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a poem which started:

- One day Haroun Al-Raschid read

- A book wherein the poet said

- Where are the kings and where the rest

- Of those who once the world possessed?

- O. Henry uses the character in his story "The Caliph And The Cad". The theme of the story is "turning the tables on Haroun al Raschid".

- Alfred Tennyson wrote a poem in his youth entitled "Recollections Of The Arabian Nights". Every stanza (except the last one) ends with "of good Haroun Alraschid".

- Harun ar-Rashid was a main figure and character in several of the stories in some of the oldest versions of the One Thousand and One Nights.

- Hārūn ar-Rashīd figures throughout James Joyce's Ulysses, in a dream of Stephen Dedalus, one of the protagonists. Stephen's efforts to recall this dream continue throughout the novel, culminating in the novel's fifteenth episode, wherein some characters also take on the guise of Hārūn.

- Harun ar-Rashid is also celebrated in a 1923 poem by W.B. Yeats, "The Gift of Harun al-Rashid".

- A story of one of Harun's wanderings provides the climax to the narrative game of titles at the end of Italo Calvino's If on a winter's night a traveler (1979). In Calvino's story, Harun wanders at night, only to be drawn into a conspiracy in which he is selected to assassinate the Caliph Harun ar-Rashid.

- The two protagonists of Salman Rushdie's 1990 novel Haroun and the Sea of Stories are Haroun and his father Rashid Khalifa.

- In the Sten science fiction novels by Allan Cole and Chris Bunch, the character of the Eternal Emperor uses the name "H. E. Raschid" when incognito; this is confirmed, in the final book of the series, as a reference to the character from Burton's translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night.

- In Roald Dahl's story The BFG, the Sultan of Baghdad says he had an uncle called Caliph Harun ar-Rashid who disappeared with his wife and ten children.

- The movie The Golden Blade (1952), starring Rock Hudson and Piper Laurie depicts the adventures of Harun who uses a magic sword to free a fairy-tale Baghdad from Jafar, the evil usurper of the throne. After he finally wins the hand of princess Khairuzan she awards him the title Al-Rashid.

- The comic book The Sandman features a story (issue 50, "Ramadan") set in the world of the One Thousand and One Nights, with Hārūn ar-Rashīd as the protagonist. It highlights his historical and mythical role as well as his discussion of the transitory nature of power. The story is included in the collection The Sandman: Fables and Reflections.

- Haroun El Poussah in the French comic strip Iznogoud is a satirical version of Hārūn ar-Rashīd.

- In Quest for Glory II, the sultan who adopts the Hero as his son is named Hārūn ar-Rashīd. He is often seen prophesying on the streets of Shapeir as The Poet Omar.

- Harun ar-Rashid appears as the leader of Arabia in the video game Civilization 5.[13]

- Future US President Theodore Roosevelt, when he was a New York Police Department Commissioner, was called in the local newspapers "Haroun-al-Roosevelt".

- In The Master and Margarita, by novelist Mikhail Bulgakov, Harun ar-Rashid is referenced by the character Korovyev in which he warns a door man not to judge him "by [his] suit," and to reference the story of "the famous caliph, Harun al-Rashid".

- In the 1924 film Waxworks, a poet is hired by a wax museum proprietor to write back-stories for three wax models. Among these wax models is Harun ar-Rashid, played by Emil Jannings.

- In the 2006 novel Variable Star by Robert Heinlein and Spider Robinson, chapter 1 is prefaced with a quotation from Alfred, Lord Tennyson's "Recollections of the Arabian Nights" regarding "good Harun Alrashid," the relevance of which becomes apparent in chapter 2 when one character relates stories (probably apocryphal and presumably drawn from Tennyson) of Harun ar-Rahsid to another character in order to use them as an analogy.

- The second chapter in the novel Prince Otto by Robert Louis Stevenson has the title "In which the Prince Plays Haroun al-Raschid".

See also

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2014) |

References

- ^ Audun Holme, Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage page 150

- ^ André Clot, Harun ar-Rashid and the world of the thousand and one nights page 97

- ^ André Clot, Harun ar-Rashid and the world of the thousand and one nights

- ^ New Arabian nights' entertainments, Volume 3

- ^ Masʻūdī, Paul Lunde, Caroline Stone, The meadows of gold: the Abbasids page 62

- ^ Tarikh ath-Thabari 4/668-669

- ^ Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidaya wa'l-Nihaya v 13 .p 650

- ^ Dennis Bloodworth, Ching Ping Bloodworth (2004). The Chinese Machiavelli: 3000 years of Chinese statecraft. Transaction Publishers. p. 214. ISBN 0-7658-0568-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Herbert Allen Giles (1926). Confucianism and its rivals. Forgotten Books. p. 139. ISBN 1-60680-248-8. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

In7= 789 the Khalifa Harun al Raschid dispatched a mission to China, and there had been one or two less important missions in the seventh and eighth centuries; but from 879, the date of the Canton massacre, for more than three centuries to follow, we hear nothing of the Mahometans and their religion. They were not mentioned in the edict of 845, which proved such a blow to Buddhism and Nestorian Christianityl perhaps because they were less obtrusive in ithe propagation of their religion, a policy aided by the absence of anything like a commercial spirit in religious matters.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Marshall Broomhall (1910). Islam in China: a neglected problem. LONDON 12 PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS, E.C.: Morgan & Scott, ltd. pp. 25, 26. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

CHAPTER II CHINA AND THE ARABS From the Rise of the Abbaside Caliphate With the rise of the Abbasides we enter upon a somewhat different phase of Moslem history, and approach the period when an important body of Moslem troops entered and settled within the Chinese Empire. While the Abbasides inaugurated that era of literature and science associated with the Court at Bagdad, the hitherto predominant Arab element began to give way to the Turks, who soon became the bodyguard of the Caliphs, " until in the end the Caliphs became the helpless tools of their rude protectors." Several embassies from the Abbaside Caliphs to the Chinese Court are recorded in the T'ang Annals, the most important of these being those of (A-bo-lo-ba) Abul Abbas, the founder of the new dynasty, that of (A-p'u-cKa-fo) Abu Giafar, the builder of Bagdad, of whom more must be said immediately; and that of (A-lun) Harun al Raschid, best known, perhaps, in modern days through the popular work, Arabian Nights.1 The Abbasides or " Black Flags," as they were commonly called, are known in Chinese history as the Heh-i Ta-shih, " The Black-robed Arabs." Five years after the rise of the Abbasides, at a time when Abu Giafar, the second Caliph, was busy plotting the assassination of his great and able rival Abu Muslim, who is regarded as " the leading figure of the age " and the de facto founder of the house of Abbas so far as military prowess is concerned, a terrible rebellion broke out in China. This was in 755 A.d., and the leader was a Turk or Tartar named An Lu-shan. This man, who had gained great favour with the Emperor Hsuan Tsung, and had been placed at the head of a vast army operating against the Turks and Tartars on the north-west frontier, ended in proclaiming his independence and declaring war upon his now aged Imperial patron. The Emperor, driven from his capital, abdicated in favour of his son, Su Tsung (756–763 A.D.), who at once appealed to the Arabs for help. The Caliph Abu Giafar, whose army, we are told by Sir William Muir, " was fitted throughout with improved weapons and armour," responded to this request, and sent a contingent of some 4000 men, who enabled the Emperor, in 757 A.d., to recover his two capitals, Sianfu and Honanfu. These Arab troops, who probably came from some garrison on the frontiers of Turkestan, never returned to their former camp, but remained in China, where they married Chinese wives, and thus became, according to common report, the real nucleus of the naturalised Chinese Mohammedans of to-day. ^ While this story has the support of the official history of the T'ang dynasty, there is, unfortunately, no authorised statement as to how many troops the Caliph really sent.1 The statement, however, is also supported by the Chinese Mohammedan inscriptions and literature. Though the settlement of this large body of Arabs in China may be accepted as probably the largest and most definite event recorded concerning the advent of Islam, it is necessary at the same time not to overlook the facts already stated in the previous chapter, which prove that large numbers of foreigners had entered China prior to this date.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); line feed character in|quote=at position 11 (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Timeline of antisemitism#Eighth century

- ^ Al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold, p. 94.

- ^ Zacny, Rob (24 December 2010). "Civilization V Field Report 2". GamePro.

Further reading

- al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold, The Abbasids, transl. Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone, Kegan paul, London and New York, 1989

- al-Tabari "The History of al-Tabari" volume XXX "The 'Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium" transl. C.E. Bosworth, SUNY, Albany, 1989.

- Clot, André (1990). Harun Al-Rashid and the Age of a Thousand and One Nights. New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 0-941533-65-4.

- Harry St John Bridger Philby. Harun al Rashid (London: P. Davies) 1933.

- Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, "Two Lives of Charlemagne," transl. Lewis Thorpe, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1977 (1969)

- John H. Haaren, Famous Men of the Middle Ages [1]

- William Muir, K.C.S.I., The Caliphate, its rise, decline, and fall [2]

- Theophanes, "The Chronicle of Theophanes," transl. Harry Turtledove, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1982

- Norwich, John J. (1991). Byzantium: The Apogee. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-53779-3.

- Zabeth, Hyder Reza (1999). Landmarks of Mashhad. Alhoda UK. ISBN 964-444-221-0.

The starting statement that he was the fifth Arab Abbasid Caliph that encompassed modern Iraq is very incomplete because abbaside caliphate during haroon's reign encompassed at least modern day Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria and parts of northern Africa.

External links

- Brentjes, Sonja (2007). "Hārūn al‐Rashīd". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 474–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) (PDF version)