Trinity (nuclear test): Difference between revisions

Additional information on the core. |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

[[File:Fission bomb assembly methods.svg|thumb|upright=1.15|To create a chain reaction a sufficient amount of radioactive material has to be brought together. This can be done in two ways. The first was preferred for Uranium and the other for Plutonium bombs.{{refn|The gun-type assembly was not tested before it was detonated at [[Hiroshima]]. Because of the novel and untried features of the implosion-bomb design, [[Fat Man]], [[J. Robert Oppenheimer]] and the other scientists at [[Los Alamos National Laboratory|Los Alamos]] decided that it was necessary to test this one before attempting to use one as a weapon against the enemy.|group = n}}]] |

[[File:Fission bomb assembly methods.svg|thumb|upright=1.15|To create a chain reaction a sufficient amount of radioactive material has to be brought together. This can be done in two ways. The first was preferred for Uranium and the other for Plutonium bombs.{{refn|The gun-type assembly was not tested before it was detonated at [[Hiroshima]]. Because of the novel and untried features of the implosion-bomb design, [[Fat Man]], [[J. Robert Oppenheimer]] and the other scientists at [[Los Alamos National Laboratory|Los Alamos]] decided that it was necessary to test this one before attempting to use one as a weapon against the enemy.|group = n}}]] |

||

U.S. and British researchers were investigating the feasibility of nuclear weapons as early as 1939. Practical development began in earnest in 1942 when these efforts were transferred to the authority of the [[U.S. Army]] and became the [[Manhattan Project]]. The weapons-development portion of this project was located at the [[ |

U.S. and British researchers were investigating the feasibility of nuclear weapons as early as 1939.{{sfn|Rhodes|1986|pp=315-321}} Practical development began in earnest in 1942 when these efforts were transferred to the authority of the [[U.S. Army]] and became the [[Manhattan Project]].{{sfn|Jones|1986|pp=30-31}} The weapons-development portion of this project was located at the [[Los Alamos Laboratory]] in northern [[New Mexico]], though much other development work was carried out at the [[University of Chicago]], [[Columbia University]] and the [[Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory|Radiation Laboratory]] at the [[University of California, Berkeley]]. |

||

{{sfn|Jones|1986|p=63}} |

|||

| ⚫ | These research, development, and production efforts focused both on the development of the necessary [[fissile]] materials to power the [[nuclear chain reaction]]s in the atomic bombs and on the design, testing, and manufacture of the bombs themselves. |

||

at the [[Clinton Engineer Works]] near [[Oak Ridge, Tennessee]] (the separation of [[uranium-235]]); the [[Hanford Engineer Works]] near [[Hanford, Washington]] (the production and separation of [[plutonium-239]]) and |

|||

From January 1944 until July 1945, large-scale production plants were set in operation, and the fissile material thus produced was then used to determine the features of the weapons. Multi-pronged research was undertaken to pursue several possibilities for bomb design. Early decisions about weapon design had been based on minute quantities of uranium-235 and [[plutonium]] that had been created in pilot plants and in physics-laboratory [[cyclotron]]s. From these experimental results, it was thought that the creation of a bomb was as simple as forming a [[critical mass]] of fissile material.<ref>{{cite web|title= The Manhattan Project / Making the Atomic Bomb|publisher=United States Department of Energy|year=1999|url=http://www.osti.gov/accomplishments/pdf/DE99001330/DE99001330.pdf|format=PDF|accessdate=2008-01-24}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The production of both uranium-235 and plutonium |

||

| ⚫ | The production of both uranium-235 and plutonium were enormous undertakings given the technology of the 1940s and accounted for 80% of the total costs of the project.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.brookings.edu/projects/archive/nucweapons/manhattan.aspx |title=The Costs of the Manhattan Project | Brookings Institution (|accessdate=10 August 2010)</ref> Theoretically, enriching uranium was feasible through pre-existing techniques in physics (e.g., modifying [[particle accelerator]] technology), though it proved difficult to scale to industrial levels and was extremely costly. |

||

Plutonium, by contrast, could theoretically be produced most easily in [[nuclear reactor]]s, but the technology and science involved was wholly new. The first experimental nuclear reactor had been developed and constructed by [[Enrico Fermi]] and his team of co-workers by the end of 1942 at the University of Chicago ([[Chicago Pile-1]]), which proved that there were no obvious physical limitations to producing a slow-neutron nuclear chain reaction. Work began on constructing large plutonium-breeding reactors at [[Hanford Site|Hanford, Washington]], in October 1943. The first reactor-bred plutonium was produced in the [[B-Reactor]], the first full-scale plutonium-production reactor in the world. The first large batch of plutonium was refined at Hanford in the "221-T plant", using the [[bismuth phosphate process]], from December 26, 1944, to February 2, 1945. This was delivered to Oppenheimer's team at the Los Alamos laboratory on February 5, 1945. In the meantime, the [[X-10 Graphite Reactor]], a scaled-down version of the Hanford reactors, was built in [[Oak Ridge, Tennessee]], and went into operation in November 1943. |

Plutonium, by contrast, could theoretically be produced most easily in [[nuclear reactor]]s, but the technology and science involved was wholly new. The first experimental nuclear reactor had been developed and constructed by [[Enrico Fermi]] and his team of co-workers by the end of 1942 at the University of Chicago ([[Chicago Pile-1]]), which proved that there were no obvious physical limitations to producing a slow-neutron nuclear chain reaction. Work began on constructing large plutonium-breeding reactors at [[Hanford Site|Hanford, Washington]], in October 1943. The first reactor-bred plutonium was produced in the [[B-Reactor]], the first full-scale plutonium-production reactor in the world. The first large batch of plutonium was refined at Hanford in the "221-T plant", using the [[bismuth phosphate process]], from December 26, 1944, to February 2, 1945. This was delivered to Oppenheimer's team at the Los Alamos laboratory on February 5, 1945. In the meantime, the [[X-10 Graphite Reactor]], a scaled-down version of the Hanford reactors, was built in [[Oak Ridge, Tennessee]], and went into operation in November 1943. |

||

| Line 82: | Line 84: | ||

Scientists were confident that an implosion device would work, but these new design difficulties were great. It was decided that a full-sized test would be required before any military use, even though it would sacrifice one of a very small number of bombs. In early 1945, plans for a July 1945 test were finalized. The uranium weapon would not be tested; its success could be more or less guaranteed by measurements ahead of time. The date of the Trinity test, Monday July 16, was established in the belief that a successful test would enhance the position of President Truman, who was scheduled to meet with Allied leaders [[Winston Churchill]] and [[Joseph Stalin]] in Potsdam, Germany on Tuesday July 17. |

Scientists were confident that an implosion device would work, but these new design difficulties were great. It was decided that a full-sized test would be required before any military use, even though it would sacrifice one of a very small number of bombs. In early 1945, plans for a July 1945 test were finalized. The uranium weapon would not be tested; its success could be more or less guaranteed by measurements ahead of time. The date of the Trinity test, Monday July 16, was established in the belief that a successful test would enhance the position of President Truman, who was scheduled to meet with Allied leaders [[Winston Churchill]] and [[Joseph Stalin]] in Potsdam, Germany on Tuesday July 17. |

||

The actual Fat Man atomic bomb, which used the same design as in the Trinity test, was exploded over [[Nagasaki]] on August 9, 1945, after the Trinity test had proven its operability in an atomic explosion. A third Fat Man bomb was expected to be ready by mid-August, if needed. |

|||

== {{Visible anchor|The gadget}} == |

== {{Visible anchor|The gadget}} == |

||

Revision as of 21:18, 18 August 2014

| Trinity | |

|---|---|

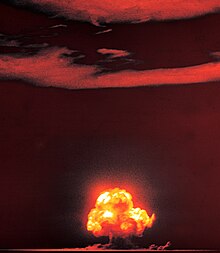

The Trinity explosion, 16 ms after detonation. | |

| Information | |

| Country | United States |

| Test site | Trinity Site, New Mexico |

| Date | July 16, 1945 |

| Test type | Atmospheric |

| Device type | Plutonium implosion fission |

| Yield | 20 kilotons of TNT (84 TJ) |

| Test chronology | |

Trinity Site | |

Trinity Site Obelisk | |

| Location | White Sands Missile Range |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | San Antonio, New Mexico |

| Area | 36,480 acres (147.6 km2)[1] |

| Built | 1945 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000493 |

| NMSRCP No. | 30 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[3] |

| Designated NHLD | December 21, 1965[4] |

| Designated NMSRCP | December 20, 1968[2] |

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army on July 16, 1945, as a result of the Manhattan Project.[5][6][7][8][9] The new test site, named the White Sands Proving Ground, was built in the Jornada del Muerto desert about 35 miles (56 km) southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range (now part of the White Sands Missile Range).[10][11]

Trinity used an implosion-design plutonium device, informally nicknamed "The Gadget" or "Christy['s] Gadget" after Robert Christy, the physicist behind the implosion method used in the device.[12][13][14] Using the same conceptual design, the Fat Man device was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. The Trinity detonation produced the explosive power of about 20 kilotons of TNT (84 TJ).

Although nuclear chain reactions had been hypothesized in 1933 and the first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction (Chicago Pile-1 or CP-1) had taken place in December 1942,[15] the date of the Trinity test is usually considered to be the beginning of the Atomic Age.[16]

History

The creation of atomic weapons arose out of political and scientific developments of the late 1930s. The rise of fascist governments in Europe, new discoveries about the nature of atoms and the fear that Nazi Germany was working on developing atomic bombs converged in the plans of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada to develop powerful weapons using nuclear fission as their primary source of energy.

In 1939 a letter was sent by prominent physicists Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning of the possibility that Nazi Germany might be attempting to build an atomic bomb.[17][18] In 1942, Roosevelt authorized the Manhattan Project, as the American nuclear physics effort was called, to research and develop a nuclear device. Although Nazi Germany was defeated in May 1945, the Manhattan Project was not disbanded, and culminated in the test explosion of a nuclear device at what is now called the Trinity Site on July 16, 1945, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a few weeks later.

The Manhattan Project

U.S. and British researchers were investigating the feasibility of nuclear weapons as early as 1939.[19] Practical development began in earnest in 1942 when these efforts were transferred to the authority of the U.S. Army and became the Manhattan Project.[20] The weapons-development portion of this project was located at the Los Alamos Laboratory in northern New Mexico, though much other development work was carried out at the University of Chicago, Columbia University and the Radiation Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

at the Clinton Engineer Works near Oak Ridge, Tennessee (the separation of uranium-235); the Hanford Engineer Works near Hanford, Washington (the production and separation of plutonium-239) and

These research, development, and production efforts focused both on the development of the necessary fissile materials to power the nuclear chain reactions in the atomic bombs and on the design, testing, and manufacture of the bombs themselves.

The production of both uranium-235 and plutonium were enormous undertakings given the technology of the 1940s and accounted for 80% of the total costs of the project.[22] Theoretically, enriching uranium was feasible through pre-existing techniques in physics (e.g., modifying particle accelerator technology), though it proved difficult to scale to industrial levels and was extremely costly.

Plutonium, by contrast, could theoretically be produced most easily in nuclear reactors, but the technology and science involved was wholly new. The first experimental nuclear reactor had been developed and constructed by Enrico Fermi and his team of co-workers by the end of 1942 at the University of Chicago (Chicago Pile-1), which proved that there were no obvious physical limitations to producing a slow-neutron nuclear chain reaction. Work began on constructing large plutonium-breeding reactors at Hanford, Washington, in October 1943. The first reactor-bred plutonium was produced in the B-Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium-production reactor in the world. The first large batch of plutonium was refined at Hanford in the "221-T plant", using the bismuth phosphate process, from December 26, 1944, to February 2, 1945. This was delivered to Oppenheimer's team at the Los Alamos laboratory on February 5, 1945. In the meantime, the X-10 Graphite Reactor, a scaled-down version of the Hanford reactors, was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and went into operation in November 1943.

Plutonium is a synthetic element not found in nature in appreciable quantities. It also has relatively complicated physics, chemistry, and metallurgy compared to most other elements. The only prior plutonium isolated for the project had been produced in cyclotrons in very minute amounts. In April 1944, Emilio Segrè received the first sample of reactor-bred plutonium from the X-10 reactor and discovered that it was not as pure as cyclotron-produced plutonium by a significant degree. Specifically, the longer the plutonium remained irradiated inside the reactor—which is necessary for high yields of the metal—the greater its content of the isotope plutonium-240. Pu-240 undergoes spontaneous fission at an appreciable rate, and that releases excess neutrons. These extra neutrons implied a high probability that a gun-type bomb with plutonium would detonate too early, before a critical mass was formed, scattering the plutonium and producing a small "fizzle" of a nuclear explosion many times smaller than a full explosion. The practical result was that a simple gun-type atomic bomb (the proposed Thin Man) would not work as had been hoped.

The impossibility of solving this problem of a gun-type bomb with plutonium was decided upon in a meeting in Los Alamos on June 17, 1944.[23] This forced a search for a different, more practical design for a plutonium-fueled bomb, and an implosion-type atomic-bomb design (i.e., the Fat Man design) was selected as the most practical one at that time. This required a great deal of research work and experimentation in engineering and hydrodynamics before a practical design could be worked out.

In an implosion bomb, a small spherical core of plutonium would be surrounded by high explosives that burned with different speeds. By alternating the faster and slower burning explosives in a carefully calculated spherical configuration, they would produce a compressive wave upon their simultaneous detonation. This "lensing" effect focused the explosive force inward with enough force to compress the plutonium core to several times its original density. This would rapidly reduce the necessary size of the critical mass of the material, making it supercritical. It would also activate a small neutron source at the center of the core, which would assure that the chain reaction began in earnest.

The advantage of the implosion method was that it was far more efficient in use of material—only 6.2 kg of plutonium would be needed for a full explosion, compared to the 64 kg of enriched uranium used in the "Little Boy" weapon. The engineering difficulties, though, were daunting. Though explosive lenses had been pursued during the war, the art was still very new, and the tolerances required in terms of timing and symmetry were unprecedented. Should the timing or symmetry be off, the bomb would not detonate fully, and instead just disperse the plutonium into the surrounding area. The entire Los Alamos laboratory was reorganized in 1944 to focus on designing a workable implosion bomb.

Scientists were confident that an implosion device would work, but these new design difficulties were great. It was decided that a full-sized test would be required before any military use, even though it would sacrifice one of a very small number of bombs. In early 1945, plans for a July 1945 test were finalized. The uranium weapon would not be tested; its success could be more or less guaranteed by measurements ahead of time. The date of the Trinity test, Monday July 16, was established in the belief that a successful test would enhance the position of President Truman, who was scheduled to meet with Allied leaders Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin in Potsdam, Germany on Tuesday July 17.

The gadget

"The gadget" was the code name given to the first bomb tested.[24] It was so called because it was not a deployable weapon and because revealing words like bomb were not used during the project for fear of espionage. It was an implosion-type plutonium device, similar in design to the Fat Man bomb used three weeks later in the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan.

In the Fat Man design, a subcritical sphere of plutonium was formed of two equal hemispheres of plutonium metal plated with silver, designated as serial numbers HS-1 and HS-2.[25] The silver plating developed blisters at Los Alamos; they were filed down and covered with gold foil; later cores were plated with nickel instead.[26][27] The sphere was placed in the center of a hollow sphere of high explosives. Numerous exploding-bridgewire detonators located on the surface of the high explosive were fired simultaneously to produce a powerful inward pressure on the core, squeezing it and increasing its density, resulting in a supercritical condition and a nuclear explosion. The actual eventual Fat Man and the "gadget" devices were not strictly "Fat Man type", as the design was modified into a production design, and both were strictly one-off prototypes.

The gadget was tested at Trinity Site, New Mexico, near Alamogordo. For the test, the gadget was lifted to the top of a 100-foot (30 m) bomb tower. It was feared by some that the Trinity test might "ignite" the earth's atmosphere, eliminating all life on the planet, although calculations had determined this was unlikely even for devices "which greatly exceed the bombs now under consideration".[28][29] Less wild estimates thought that New Mexico would be incinerated. Calculations showed that the yield of the device would be between 0 (if it did not work) and 20 kilotons of TNT (84 TJ). In the aftermath of the test, it appeared to have been a blast equivalent to 18 kilotons of TNT (75 TJ).

Test planning

In March 1944, planning for the test was assigned to Kenneth Bainbridge, a professor of physics at Harvard University, working under explosives expert George Kistiakowsky. A site had to be located that would guarantee secrecy of the project's goals even as a nuclear weapon of unknown strength was detonated. Proper scientific equipment had to be assembled for retrieving data from the test itself, and safety guidelines had to be developed to protect personnel from the unknown results of a highly dangerous experiment. Official test photographer Berlyn Brixner set up dozens of cameras to capture the event on film.

Test site

The heads of the project considered eight candidate sites, including San Nicolas Island (California), Padre Island (Texas), San Luis Valley, El Malpais National Monument, and other parts of New Mexico. A Mojave Desert Army base near Rice, California was considered the best location, but was opted against because General Leslie Groves, military head of the project, did not wish to have any dealings with the commander of the base, whom he disliked.[30] The site finally chosen was at the northern end of the White Sands Proving Ground, in Socorro County between the towns of Carrizozo and San Antonio, in the Jornada del Muerto in the southwestern United States (33°40′38″N 106°28′31″W / 33.6773°N 106.4754°W).[31] In late 1944, soldiers started arriving at Trinity Site to prepare for the test. Sgt. Marvin Davis and his military police unit arrived at the site from Los Alamos on December 30, 1944. This unit set up initial security checkpoints around the area, with plans to use horses for patrols. The distances around the site proved too great, so they resorted to using jeeps and trucks for transportation.

Throughout 1945, other personnel arrived at Trinity Site to help prepare for the bomb test. As the soldiers at Trinity Site settled in, they became familiar with Socorro County. They tried to use water out of the ranch wells, but found the water so alkaline they could not drink it. They were forced to use U.S. Navy saltwater soap and hauled drinking water in from the firehouse in Socorro.

Three bunkers were set up to observe the test.[32] Oppenheimer and Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell watched from the South bunker 5.7 miles (9.2 km) from the detonation, while Gen. Leslie Groves watched from the base camp 10 miles (16 km) away.[33]

Name

The exact origin of the name Trinity for the test is unknown, but it is often attributed to laboratory leader J. Robert Oppenheimer as a reference to the poetry of John Donne. In 1962, General Groves wrote to Oppenheimer about the origin of the name, asking if he had chosen it because it was a name common to rivers and peaks in the West and would not attract attention, and elicited this reply:[34]

I did suggest it, but not on that ground... Why I chose the name is not clear, but I know what thoughts were in my mind. There is a poem of John Donne, written just before his death, which I know and love. From it a quotation: "As West and East / In all flatt Maps—and I am one—are one, / So death doth touch the Resurrection."[35][36] That still does not make a Trinity, but in another, better known devotional poem Donne opens, "Batter my heart, three person'd God;—."[37][38]

Test predictions

The observers set up a betting pool on the results of the test,[39][40] with predictions ranging from zero (a complete dud) to 45 kilotons of TNT (190 TJ). Physicist I. I. Rabi won the pool with a prediction of 18 kilotons of TNT (75 TJ).[41]

In addition Fermi personally offered to take wagers among the top physicists and military present on whether the atmosphere would ignite, and if so whether it would destroy just the state, or incinerate the entire planet.[42] This last result had been previously calculated to be almost impossible,[29][43] although for a while it had caused some of the scientists some anxiety. Rhodes speculates that Fermi may have been making a point about a "new force being loosed on the Earth", and how little really was known about it. Bainbridge was furious with Fermi for scaring the guards who, unlike the physicists, did not have the advantage of their knowledge about the scientific possibilities.

Test preparation

A pre-test calibration explosion of 100 tons of TNT (420 GJ), spiked with 1,000 curies (37 TBq) of fission products from the Hanford B Reactor, was detonated on a wooden platform 800 yards (730 m) to the south-east of Trinity ground zero (33°40′16″N 106°28′20″W / 33.67123°N 106.47229°W) on May 7. The fireball of the conventional explosion was visible 60 miles (97 km) away.[44] The smaller explosion proved an invaluable experiment that helped scientists prepare instruments in time to study the atomic bomb explosion two months later.

For the actual test, the plutonium-core nuclear device, referred to as "the gadget," was hoisted to the top of a 100-foot (30 m) steel tower for detonation—the height would give a better indication of how the weapon would behave when dropped from an airplane, as detonation in the air would maximize the amount of energy applied directly to the target (as it expanded in a spherical shape) and would generate less nuclear fallout.

General Groves had ordered the construction of a 214-short-ton (194 t) steel canister code-named "Jumbo" to recover valuable plutonium if the 5 short tons (4.5 t) of conventional explosives failed to compress it into a chain reaction. The container was constructed at great expense in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and brought to the test site by rail, but by the time it arrived, the confidence of the scientists was high enough that they decided not to use it. Instead, it was hoisted up in a steel tower 800 yards (730 m) from the gadget to give observers a rough measure of the impact the gadget would have at that distance. In the end, Jumbo survived; its tower did not.[45]

The detonation was initially planned for 4:00 am but was postponed because of rain and lightning from early that morning. It was feared that the danger from radiation and fallout would be greatly increased by rain, and lightning had the scientists concerned about accidental detonation.[46]

-

The 100-foot-tall tower constructed for the test

-

Men stack crates of high explosives for the 100 ton test

-

The explosives of the gadget were raised up to the top of the tower for the final assembly.

-

The Jumbo container being brought to the site.

-

Trinity Site (red arrow) near Carrizozo Malpais

Explosion

At 04:45, a crucial weather report came in favorably, and, at 05:10, the twenty-minute countdown began. Most top-level scientists and military officers were observing from a base camp 10 miles (16 km) southwest of the test tower.[citation needed] Many other observers were around 20 miles (32 km) away, and some others were scattered at different distances, some in more informal situations (physicist Richard Feynman claimed to be the only person to see the explosion without the dark glasses provided, relying on a truck windshield to screen out harmful ultraviolet wavelengths).[47] The final countdown was read by physicist Samuel K. Allison.

At 05:29:21 (plus or minus 2 seconds)[48] local time (Mountain War Time), the device exploded with an energy equivalent to around 20 kilotons of TNT (84 TJ). It left a crater of radioactive glass in the desert 10 feet (3.0 m) deep and 1,100 feet (340 m) wide. At the time of detonation, the surrounding mountains were illuminated "brighter than daytime" for one to two seconds, and the heat was reported as "being as hot as an oven" at the base camp. The observed colors of the illumination ranged from purple to green and eventually to white. The roar of the shock wave took 40 seconds to reach the observers.[40] The shock wave was felt over 100 miles (160 km) away, and the mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles (12.1 km) in height. After the initial euphoria of witnessing the explosion had passed,[n 2] test director Kenneth Bainbridge commented to Los Alamos director J. Robert Oppenheimer, "Now we are all sons of bitches."[50] Oppenheimer later stated that, while watching the test, he was reminded of a line from the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu scripture: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."[n 3]

Physicist Isidor Rabi noticed Oppenheimer's disconcerting triumphalism: "I'll never forget his walk; I'll never forget the way he stepped out of the car...his walk was like High Noon...this kind of strut. He had done it."[52]

In the official report on the test, General Farrell wrote, "The lighting effects beggared description. The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined..."[53]

News reports quoted a forest ranger 150 miles (240 km) west of the site as saying he saw "a flash of fire followed by an explosion and black smoke." A New Mexican 150 miles (240 km) north said, "The explosion lighted up the sky like the sun." Other reports remarked that windows were rattled and the sound of the explosion could be heard up to 200 miles (320 km) away.

John R. Lugo was flying a U.S. Navy transport at 10,000 feet (3,000 m), 30 miles (48 km) east of Albuquerque, en route to the west coast. "My first impression was, like, the sun was coming up in the south. What a ball of fire! It was so bright it lit up the cockpit of the plane." Lugo radioed Albuquerque. He got no explanation for the blast but was told, "Don't fly south."[54]

In the crater, the desert sand, which is largely made of silica, melted and became a mildly radioactive light green glass, which was named trinitite.[55] The crater was filled in soon after the test.

The Alamogordo Air Base issued a 50-word press release in response to what it described as "several inquiries" that had been received concerning an explosion. The release explained that "a remotely located ammunitions magazine containing a considerable amount of high explosives and pyrotechnics exploded," but that "there was no loss of life or limb to anyone." A newspaper article published the same day stated that "the blast was seen and felt throughout an area extending from El Paso to Silver City, Gallup, Socorro, and Albuquerque."[56] An Associated Press article quoted a blind woman 150 miles (240 km) away who asked "What's that brilliant light?" Such articles appeared in New Mexico, but East coast newspapers ignored them.[57]

The air base press release was written by William L. Laurence of The New York Times, who was aware of the Manhattan Project. He had prepared four releases for a variety of outcomes,[57] ranging from an account of a successful test (the one which was used) to more catastrophic scenarios involving serious damage to surrounding communities, evacuation of nearby residents, and a placeholder for the names of those killed in the explosion.[58][59] As Laurence was a witness to the test he knew that the last release, if used, would be his obituary.[57]

Around 260 personnel were present, none closer than 5.6 miles (9.0 km). At the next test series, Operation Crossroads in 1946, over 40,000 people were present.[60]

The official technical report (LA-6300-H) on the history of the Trinity test was released in May 1976.[61]

-

Film of the Trinity test

-

Ground zero after the test

-

An aerial photograph of the Trinity crater shortly after the test.[n 4]

-

Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves and Robert Oppenheimer at the Trinity shot tower remains a few weeks later.

-

The Jumbo container after the test

Test results

The results of the test were conveyed to President Harry S. Truman, who was eagerly awaiting them at the Potsdam Conference; the coded message ("Operated this morning. Diagnosis not complete but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations ... Dr. Groves pleased.") arrived at 7:30 p.m. on July 16 and was at once taken to the president and Secretary of State James F. Byrnes at the "Little White House" in the Berlin suburb of Babelsberg by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.[62] Information about the Trinity test was made public shortly after the bombing of Hiroshima. The Smyth Report, released on August 12, 1945, gave some information on the blast, and the hardbound edition released by Princeton University Press a few weeks later contained the famous pictures of a "bulbous" Trinity fireball.

Oppenheimer and Groves posed for reporters near the remains of the mangled test tower shortly after the war. In the years after the test, the pictures have become a potent symbol of the beginning of the so-called Atomic Age, and the test has often been featured in popular culture.

First deployment

Following the success of the Trinity test, two bombs were prepared for use against Japan during World War II. The first, dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, was code-named "Little Boy", and used the "gun" design and uranium-235 as its fission source. It was an untested design but was considered very likely to work and was considerably simpler than the implosion model. It could not be tested, because there was only enough uranium-235 for one bomb. The second bomb, dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, was code-named "Fat Man" and was an implosion-type plutonium bomb. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed at least 148,000 people and many more over time. By 1950, the death toll was over 340,000.[63][better source needed] They were followed days later by the surrender of Japan. Debate over the justification of the use of nuclear weapons against Japan persists to this day, both in scholarly and popular circles.

Civilian detection

Shortly after the Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the Kodak Company observed some spotting/fogging on their film which was, at the time, usually packaged in cardboard containers. Dr. J. H. Webb, a Kodak employee, studied the matter and concluded that the contamination must have come from a nuclear explosion somewhere in the United States. He discounted the possibility that Little Boy was responsible due to the timing of the events. A hot spot of fallout from the Trinity explosion had contaminated the river water that the paper mill in Indiana used to manufacture the cardboard pulp from corn husks,[64] aware of the gravity of his discovery, Dr. Webb kept this secret until 1949.[65] The physicist's knowledge of the secret project was not altogether surprising considering that the Kodak Company ran the Tennessee Eastman uranium processing plant at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.[66]

This incident, along with the next continental US tests in 1951 set a precedent, and in all subsequent atmospheric nuclear tests at the Nevada test site(1951-1962), AEC officials gave the photographic industry maps and forecasts of potential contamination, as well as expected fallout distributions which enabled them to purchase uncontaminated materials and take other protective measures.[67]

Fallout effects

The heaviest fallout contamination outside the restricted test area was 30 miles from the detonation point, on Chupadera mesa where cattle grazed, the radioactivity here is reported to have settled in a white mist onto a number of the livestock in the area, resulting in local beta burns and a temporary loss of dorsal/back hair. Patches of hair grew back discolored as white fur. The army bought 75 cattle in all from ranchers; the 17 most significantly marked were kept at Los Alamos, while the rest were shipped to Oak Ridge for long term observation.[68][69][70][71]

Maps of the ground dose rate pattern from the device's fallout at +1 hour,[72] and +12 hours,[73] after detonation are available. Unlike the 100 or so atmospheric nuclear explosions at the Nevada Test Site, conducted later, fallout doses to the local inhabitants have not been reconstructed for the Trinity event, due primarily to scarcity of data.[74]

Site today

In 1952, the site of the explosion was bulldozed, and the remaining trinitite was disposed of. On December 21, 1965, the 51,500-acre (20,800 ha) area Trinity Site was declared a National Historic Landmark district[1][4] and, on October 15, 1966, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

The landmark includes the base camp, where the scientists and support group lived; ground zero, where the bomb was placed for the explosion; and the Schmidt/McDonald ranch house, where the plutonium core to the bomb was assembled. Visitors to a Trinity Site open house are allowed to see the ground zero and ranch house areas. In addition, one of the old instrumentation bunkers is visible beside the road just west of ground zero.

In September 1953, about 650 people attended the first Trinity Site open house. In 1967, the inner oblong fence was added. In 1972, the corridor barbed wire fence that connects the outer fence to the inner one was completed. Jumbo was moved to the parking lot in 1979; it is missing its ends from an attempt to destroy it in 1946 using eight 500-pound (230 kg) bombs.[75]

More than sixty years after the test, residual radiation at the site measured about ten times higher than normal.[76] The amount of radioactive exposure received during a one-hour visit to the site is about half of the total radiation exposure which a U.S. adult receives on an average day from natural and medical sources.[77] The Trinity monument, a rough-sided, lava-rock obelisk around 12 feet (3.7 m) high, marks the explosion's hypocenter, and Jumbo is still kept nearby.

On July 16, 1995, a special tour of the site was conducted to mark the 50th anniversary of the Trinity test, and about 5,000 visitors arrived to commemorate the occasion, the largest crowd for any open house. Since that large crowd, the open houses usually average two to three thousand visitors. The site is still a popular destination for those interested in atomic tourism, though it is only open to the public once a year during the Trinity Site Open House on the first Saturday in April.[78]

-

Trinity Site Historical Marker, 2008

-

Remnants of Jumbo, 2010

-

Tourists At Ground Zero, 2007

See also

- First Lightning (RDS-1) (Joe-1): the first Soviet atomic bomb test (with a device modeled after the type used at the Trinity test)

- Nuclear weapons and the United States

- List of nuclear tests

- Day of Trinity, a 1965 book by Lansing Lamont

- The Day After Trinity, a 1980 documentary film

- Trinity, a 1986 interactive fiction Infocom video game that centers around the Trinity test

- Day One, a 1989 film

- Doctor Atomic, an opera about the Trinity test

- Trinity Mass, a 1984 musical work by James Yannatos

- Stallion Gate, a 1986 novel by Martin Cruz Smith, centered around the Trinity test

- Trinity and Beyond, a 1995 documentary film

- Ivy Mike, the codename given to the first United States nuclear test of a fusion device on November 1, 1952

- Above and Beyond, a 1952 film about the planning and dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima

- Fat Man and Little Boy, a 1989 film that reenacts the Manhattan Project

- The Gadget (novel), a fiction novel set on the Trinity test

- Trinity's Child, a fictional novel set in the late 20th Century, depicting a nuclear war started by artifice.

Notes

- ^ The gun-type assembly was not tested before it was detonated at Hiroshima. Because of the novel and untried features of the implosion-bomb design, Fat Man, J. Robert Oppenheimer and the other scientists at Los Alamos decided that it was necessary to test this one before attempting to use one as a weapon against the enemy.

- ^ The New York Times journalist William L. Laurence recalls "A loud cry filled the air. The little groups that hitherto had stood rooted to the earth like desert plants broke into dance." Physicist Isidor Rabi said "[Oppenheimer's] walk was like High Noon...this kind of strut. He had done it."[49]

- ^ Variants on this quotation exist, both by Oppenheimer and by others. A more common translation of the passage, from Arthur W. Ryder (from whom Oppenheimer studied Sanskrit at Berkeley in the 1930s), is:

- Death am I, and my present task

- Destruction. (11:32)

- If the radiance of a thousand suns

- were to burst into the sky,

- that would be like

- the splendor of the Mighty One—

- I am become Death, the shatterer of Worlds.

- ^ The small crater in the southeast corner was from the earlier test explosion of 108 tons of TNT (450 GJ).

References

- ^ a b Richard Greenwood (January 14, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Trinity Site" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Template:PDFlink - ^ "New Mexico State and National Registers". New Mexico Historic Preservation Commission. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Trinity Site". National Historic Landmarks. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ^ Ferenc Morton Szasz, The Day The Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion July 16, 1945 (University of New Mexico Press, 1984). ISBN 978-0-8263-0768-2

- ^ "The First Atomic Bomb Blast, 1945". Eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Chris Demarest. "Atomic Bomb-Truman Press Release-August 6, 1945". Trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Final Preparations for Rehearsals and Test | The Trinity Test | Historical Documents". atomicarchive.com. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "TRINITY TEST - JULY 16, 1945". Radiochemistry.org. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Safety and the Trinity Test, July 1945". Cfo.doe.gov. Retrieved 2010-02-28.[dead link]

- ^ "Atomic Bomb: Decision - Trinity Test, July 16, 1945". Dannen.com. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Constructing the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb".

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993, pp. 293, 307–308.

- ^ Holl, Jack (1997). Argonne National Laboratory, 1946-96. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02341-2.

- ^ Laurence, W. L. (1945-09-26). "Drama of the Atomic Bomb Found Climax in July 16 Test". The New York Times. Retrieved October 03, 2013

- ^ AIP.org

- ^ Atomicarchive.com

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 315–321.

- ^ Jones 1986, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Jones 1986, p. 63.

- ^ {{cite web |url=http://www.brookings.edu/projects/archive/nucweapons/manhattan.aspx |title=The Costs of the Manhattan Project | Brookings Institution (|accessdate=10 August 2010)

- ^ Manhattan Project Chronology at AtomicArchive.com

- ^ Westcott, Kathryn (15 July 2005). "The day the world lit up". BBC News.

- ^ Wellerstein, Alex. "The third core's revenge". Restricted data blog. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ Wellerstein, Alex. "You don't know Fat Man". Restricted data blog. Retrieved 2014-04-04.

- ^ Coster-Mullen, John (2010). Core Differences, from "Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man". Retrieved 3014-04-04.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) An error: the illustration caption states the Fat Man core was plated in silver; it was plated in nickel, as the silver plating on the gadget core blistered. The disk in the drawings is a gold foil gasket. - ^ Richard Hamming (1998). "Mathematics on a Distant Planet". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (7): 640–650. doi:10.2307/2589247.

- ^ a b "Report LA-602, "Ignition of the Atmosphere With Nuclear Bombs"" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ^ "Trinity Atomic Web Site". Walker, Gregory. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ^ "Trinity Site". White Sands Missile Range. Archived from the original on 2008-06-01. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

GPS Coordinates for obelisk (exact GZ) = N33.40.636 W106.28.525

- ^ Rhodes, p. 653.

- ^ Rhodes, p. 675.

- ^ Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986), pp. 571–572.

- ^ John Donne, "Hymne to God My God, in My Sicknesse". The excerpt is about half of the third five-line stanza out of six.

- ^ Hymn to god, my god, in my sickness Source: Donne, John. Poems of John Donne. vol I. E. K. Chambers, ed. London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1896. 211–212.

- ^ John Donne, Holy Sonnets, XIV. The clause is the truncated first line of a four-line sentence from the (14-line) sonnet.

- ^ Holy sonnets. XIV Source: Donne, John. Poems of John Donne. vol I. E. K. Chambers, ed. London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1896. 165.

- ^ Rhodes, pages 656.

- ^ a b James Hershberg (1993), James B. Conant: Harvard to Hiroshima and the Making of the Nuclear Age. 948 pp. ISBN 0-394-57966-6 p. 233

- ^ Rhodes, p. 677.

- ^ Rhodes, p. 664.

- ^ Richard Hamming. "Mathematics on a Distant Planet".

- ^ http://www.radiochemistry.org/history/manhattan/04_pdf/05.pdf

- ^ "Moving "Jumbo" at the Trinity Test Site". Brookings Institution Press. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ "Countdown" (PDF). Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era, 1943–1945. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. ca. 1967–1971. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)[dead link] - ^ Richard Feynman (2000), The Pleasure of Finding Things Out p. 53–96 ISBN 0-7382-0349-1

- ^ Guttenberg, B. (1946). "Interpretation of Records Obtained from the New Mexico Atomic Test, July 16, 1945". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 36: 327–330.

- ^ Ray Monk (2012). Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Jonathan Cape. pp. 440–. ISBN 978-0-224-06262-6. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "The Trinity Test". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986). Quotes after the test from p. 675–676.

- ^ Monk, Ray (2012). Robert Oppenheimer: A Life Inside the Center. New York; Toronto: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50407-2. pp.456-457.

- ^ "Chronology on Decision to Bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki".

- ^ Larry Calloway (May 10, 2005). "The Trinity Test: Eyewitnesses". Archived from the original on 2005-10-18.

- ^ P.P. Parekh (2006). "Radioactivity in Trinitite six decades later". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 85 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2005.01.017. PMID 16102878.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Army Ammunition Explosion Rocks Southwest Area," El Paso Herald-Post, 1945-7-16, p.1 (quoting the full press release)(retrieved from Newspaperarchive.com 2007-8-15).

- ^ a b c Sweeney, Michael S. (2001). Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the American Press and Radio in World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 0-8078-2598-0.

- ^ William L. Laurence, "Now We Are All Sons-of-Bitches," Science News vol. 98, no. 2 (11 July 1970): pp. 39–41.

- ^ "Weekly Document #1: Trinity test press releases (May 1945)". Also the text of the press releases.

- ^ "Operation Crossroads: Fact Sheet". Department of the navy—naval historical center. 2002-08-11. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ Bainbridge, K.T., Trinity (Report LA-6300-H), Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory.

- ^ Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of an American Myth (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), p. 240.

- ^ From: Hughes, Jeff. The Manhattan Project: Big Science and The Atom Bomb. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002. (p.95)

- ^ "Let Them Drink Milk By: Pat Ortmeyer and Arjun Makhijani Article published as "Worse Than We Knew," for November/December 1997 issue of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists".

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 57 (help) - ^ "Oak Ridge's Merril Eisenbud - Hiroshima, the Trinity Test, Nuclear Weapons. - discussing Webb, J.H., The Fogging of Photographic Film by Radioactive Contaminants in Cardboard Packaging Materials, Physical Review Vol. 76 (3):375-380, 1949".

- ^ "Let Them Drink Milk By: Pat Ortmeyer and Arjun Makhijani Article published as "Worse Than We Knew," for November/December 1997 issue of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists".

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 57 (help) - ^ "Let Them Drink Milk By: Pat Ortmeyer and Arjun Makhijani Article published as "Worse Than We Knew," for November/December 1997 issue of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists".

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 57 (help) - ^ "INTERIM REPORT OF CDC'S LAHDRA PROJECT – Appendix N. pg 17, 23, 37" (PDF).

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Fire Research, United States. Office of Civil Defense (1969). Mass burns: proceedings of a workshop, 13–14 March 1968. National Academies. p. 248.

- ^ Barton C. Hacker (1987). The dragon's tail: radiation safety in the Manhattan Project, 1942-1946. University of California Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-520-05852-6.

- ^ Ferenc Morton Szasz (1984). The day the sun rose twice: the story of the Trinity Site nuclear explosion, July 16, 1945. UNM Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-8263-0768-X.

- ^ "INTERIM REPORT OF CDC'S LAHDRA PROJECT – Appendix N. Figure 19" (PDF).

- ^ "INTERIM REPORT OF CDC'S LAHDRA PROJECT – Appendix N. Figure 20" (PDF).

- ^ "INTERIM REPORT OF CDC'S LAHDRA PROJECT – Appendix N. pg 36 - 37" (PDF).

- ^ "Trinity Atomic Website: Jumbo". Virginia Tech Center for Digital Discourse and Culture. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ Brian Greene (2003), Nova: The Elegant Universe: Einstein's Dream. PBS Nova transcript Regarding residual radiation.

- ^ WSMR article on Trinity nuclear test site

- ^ "Trinity Site". White Sands Missile Range, Public Affairs Office. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

External links

- Official report LA-6300-H by Bainbridge, declassified as a "comprehensive record" in 1976 and containing "almost all the original text previously published as LA-1012".

- Very High Resolution Photograph of The Trinity Obelisk

- Trinity Remembered: 60th Anniversary

- BBC article on the 60th Anniversary

- Atomic tourism: Information for visitors[dead link]

- The Trinity test on the Los Alamos National Laboratory website

- Carey Sublette's Nuclear Weapon Archive Trinity page

- The Trinity test on the Sandia National Laboratories website

- The Trinity Site on the White Sands Missile Range website

- Richard Feynman, "Los Alamos from Below"; Surely, You're Joking, Mr. Feynman.

- Trinity Test Fallout Pattern

- Trinity Test Photographs

- Trinity: First Test of the Atomic Bomb

- "My Radioactive Vacation", report of a visit to the Trinity site, with pictures comparing its past with its present state

- Visiting Trinity Short article by Ker Than at 3 Quarks Daily

- "War Department release on New Mexico test, July 16, 1945", from the Smyth Report, with eyewitness reports from Gen. Groves and Gen. Farrell (1945)

- Trinity Site National Historic Landmark

- Trinity A bomb test photos on The UK National Archives' website.

- Annotated bibliography for the Trinity Test from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Video of the Trinity Weapon Test at sonicbomb.com

- The short film Nuclear Test Film - Trinity Shot (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Nuclear Test Film - Nuclear Testing Review (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Atomic Weapons Tests: TRINITY through BUSTER-JANGLE (1952) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film WORLD CELEBRATES PEACE, VJ DAY, 08/12/1945 (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive. (WORLD IN FILM, ISSUE NUMBER 19 - THE ATOM BOMB)

- 1945 in science

- 1945 in the United States

- 1945 in New Mexico

- American nuclear weapons testing

- Explosions in the United States

- History of New Mexico

- Manhattan Project

- National Historic Landmarks in New Mexico

- New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties

- Nuclear history of the United States

- History of Socorro County, New Mexico

- Tularosa Basin

- Visitor attractions in Alamogordo, New Mexico

- 20th-century explosions

- Code names

- Historic districts in New Mexico

- Visitor attractions in Socorro County, New Mexico

- Military facilities on the National Register of Historic Places in New Mexico

![An aerial photograph of the Trinity crater shortly after the test.[n 4]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/01/Trinity_crater_%28annotated%29_2.jpg/199px-Trinity_crater_%28annotated%29_2.jpg)