Daguerreotype: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Since the late [[Renaissance]], artists and inventors had searched for a mechanical method of capturing visual scenes.<ref name="stokstad_964-967">{{Cite book |last = Stokstad |first = Marilyn |authorlink = Marilyn Stokstad |author2=David Cateforis |author3=Stephen Addiss |title = Art History |publisher = Pearson Education |year = 2005 |location = Upper Saddle River, New Jersey |pages = 964–967 |edition = Second |isbn = 0-13-145527-3}}</ref> Previously, using the [[camera obscura]], artists would manually trace what they saw, or use the optical image in the camera as a basis for solving the problems of [[Perspective (graphical)|perspective]] and [[parallax]], and deciding color values. The camera obscura's optical reduction of a real scene in [[three-dimensional space]] to a flat rendition in [[Two-dimensional space|two dimensions]] influenced [[Western art history|western art]], so that at one point, it was thought that images based on optical geometry (perspective) belonged to a more advanced civilization. Later, with the advent of [[Modernism]], the absence of perspective in [[History of Eastern art|oriental art]] from [[China]], [[Japan]] and in [[Persia]]n miniatures was revalued. |

Since the late [[Renaissance]], artists and inventors had searched for a mechanical method of capturing visual scenes.<ref name="stokstad_964-967">{{Cite book |last = Stokstad |first = Marilyn |authorlink = Marilyn Stokstad |author2=David Cateforis |author3=Stephen Addiss |title = Art History |publisher = Pearson Education |year = 2005 |location = Upper Saddle River, New Jersey |pages = 964–967 |edition = Second |isbn = 0-13-145527-3}}</ref> Previously, using the [[camera obscura]], artists would manually trace what they saw, or use the optical image in the camera as a basis for solving the problems of [[Perspective (graphical)|perspective]] and [[parallax]], and deciding color values. The camera obscura's optical reduction of a real scene in [[three-dimensional space]] to a flat rendition in [[Two-dimensional space|two dimensions]] influenced [[Western art history|western art]], so that at one point, it was thought that images based on optical geometry (perspective) belonged to a more advanced civilization. Later, with the advent of [[Modernism]], the absence of perspective in [[History of Eastern art|oriental art]] from [[China]], [[Japan]] and in [[Persia]]n miniatures was revalued. |

||

Previous discoveries of photosensitive methods and substances — including [[silver nitrate]] by [[Albertus Magnus]] in the 13th century,<ref>{{Cite book |last = Szabadváry |first = Ferenc |title = History of analytical chemistry |publisher = Taylor & Francis |year = 1992 |location = |page = 17 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=53APqy0KDaQC |isbn = 2-88124-569-2}}</ref> a silver and chalk mixture by [[Johann Heinrich Schulze]] in 1724,<ref name="Watt2003">{{cite book|author=Susan Watt|title=Silver|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=TYPyWkuRJqYC&pg=PA21|accessdate=28 July 2013|year=2003|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|isbn=978-0-7614-1464-3|pages=21–|quote=... But the first person to use this property to produce a photographic image was German physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze. In 1727, Schulze made a paste of silver nitrate and chalk, placed the mixture in a glass bottle and wrapped the bottle in ...}}</ref> and [[Nicéphore Niépce|Joseph Niépce]]'s [[bitumen]]-based [[heliography]]<ref name="stokstad_964-967" /> in 1822<ref name="utexas">{{cite web |title=The First Photograph - Heliography |url=http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/wfp/heliography.html |quote=from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ... In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate ... The sunlight passing through ... This first permanent example ... was destroyed ... some years later. |accessdate=2009-09-29}}</ref> — contributed to development of the daguerreotype. The first reliably documented attempt to capture the image formed in a [[camera obscura]] was made by [[Thomas Wedgwood (photographer)|Thomas Wedgwood]] as early as the 1790s, but according to an 1802 account of his work |

Previous discoveries of photosensitive methods and substances — including [[silver nitrate]] by [[Albertus Magnus]] in the 13th century,<ref>{{Cite book |last = Szabadváry |first = Ferenc |title = History of analytical chemistry |publisher = Taylor & Francis |year = 1992 |location = |page = 17 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=53APqy0KDaQC |isbn = 2-88124-569-2}}</ref> a silver and chalk mixture by [[Johann Heinrich Schulze]] in 1724,<ref name="Watt2003">{{cite book|author=Susan Watt|title=Silver|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=TYPyWkuRJqYC&pg=PA21|accessdate=28 July 2013|year=2003|publisher=Marshall Cavendish|isbn=978-0-7614-1464-3|pages=21–|quote=... But the first person to use this property to produce a photographic image was German physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze. In 1727, Schulze made a paste of silver nitrate and chalk, placed the mixture in a glass bottle and wrapped the bottle in ...}}</ref> and [[Nicéphore Niépce|Joseph Niépce]]'s [[bitumen]]-based [[heliography]]<ref name="stokstad_964-967" /> in 1822<ref name="utexas">{{cite web |title=The First Photograph - Heliography |url=http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/wfp/heliography.html |quote=from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ... In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate ... The sunlight passing through ... This first permanent example ... was destroyed ... some years later. |accessdate=2009-09-29}}</ref> — contributed to development of the daguerreotype. |

||

The first reliably documented attempt to capture the image formed in a [[camera obscura]] was made by [[Thomas Wedgwood (photographer)|Thomas Wedgwood]] as early as the 1790s, but according to an 1802 account of his work by Sir [[Humphrey Davy]]: |

|||

"''The images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedgwood in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful.''"<ref>[http://www.luminous-lint.com/app/contents/fra/_source_humphry_davy_and_thomas_wedgwood_01/ Fragment > An Account of a method of copying Paintings upon glass, and of making Profiles, by the agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. WEDGWOOD, ESQ. With Observations by H. DAVY. (1802) ] </ref> |

|||

In 1829 [[France|French]] artist and [[chemist]] [[Louis Daguerre|Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre]], contributing a cutting edge camera design, partnered with Niépce, a leader in [[photochemistry]], to further develop their technologies.<ref name="stokstad_964-967" /> The two men came into contact through their optician, Chevalier, who supplied lenses for their camerae obscurae. |

In 1829 [[France|French]] artist and [[chemist]] [[Louis Daguerre|Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre]], contributing a cutting edge camera design, partnered with Niépce, a leader in [[photochemistry]], to further develop their technologies.<ref name="stokstad_964-967" /> The two men came into contact through their optician, Chevalier, who supplied lenses for their camerae obscurae. |

||

Revision as of 13:08, 18 September 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The daguerreotype /dəˈɡɛr[invalid input: 'ɵ']taɪp/ (French: daguerréotype) process (also called daguerreotypy), introduced in 1839, was the first publicly announced photographic process and the first to come into widespread use. By the early 1860s, later processes which were less expensive and produced more easily viewed images had almost entirely replaced it. A small-scale revival of daguerreotypy among photographers interested in historical processes was increasingly apparent during the 1980s and 1990s and has persisted into the 2010s.

The distinguishing visual characteristics of a daguerreotype are that the image is on a bright (ignoring any areas of tarnish) mirror-like surface of metallic silver and it will appear either positive or negative depending on the lighting conditions and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal.

Several types of antique images, particularly ambrotypes and tintypes but sometimes even old prints on paper, are commonly misidentified as daguerreotypes, especially if they are in the small, ornamented cases in which daguerreotypes were usually housed. The name "daguerreotype" correctly refers only to one very distinctive image type and medium, produced by a specific photographic process that was in wide use only from the early 1840s to the late 1850s.

Invention

Since the late Renaissance, artists and inventors had searched for a mechanical method of capturing visual scenes.[1] Previously, using the camera obscura, artists would manually trace what they saw, or use the optical image in the camera as a basis for solving the problems of perspective and parallax, and deciding color values. The camera obscura's optical reduction of a real scene in three-dimensional space to a flat rendition in two dimensions influenced western art, so that at one point, it was thought that images based on optical geometry (perspective) belonged to a more advanced civilization. Later, with the advent of Modernism, the absence of perspective in oriental art from China, Japan and in Persian miniatures was revalued.

Previous discoveries of photosensitive methods and substances — including silver nitrate by Albertus Magnus in the 13th century,[2] a silver and chalk mixture by Johann Heinrich Schulze in 1724,[3] and Joseph Niépce's bitumen-based heliography[1] in 1822[4] — contributed to development of the daguerreotype.

The first reliably documented attempt to capture the image formed in a camera obscura was made by Thomas Wedgwood as early as the 1790s, but according to an 1802 account of his work by Sir Humphrey Davy:

"The images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedgwood in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful."[5]

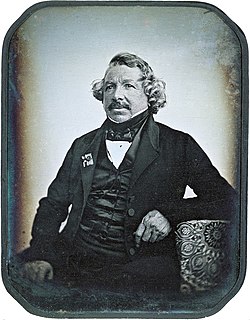

In 1829 French artist and chemist Louis Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, contributing a cutting edge camera design, partnered with Niépce, a leader in photochemistry, to further develop their technologies.[1] The two men came into contact through their optician, Chevalier, who supplied lenses for their camerae obscurae.

Niépce's aim originally had been to find a method to reproduce prints and drawings for lithography. He had started out experimenting with light sensitive materials and had made a contact print from a drawing and then went on to successfully make the first photomechanical record of an image in a camera obscura—the world's first photograph. Niépce's method was to coat a metal plate with bitumen of Judea (asphalt) and the action of the light differentially hardened the bitumen. The plate was washed with oil of lavender leaving a relief image. Niépce called his process heliography and the exposure for the first successful photograph was eight hours.

After Niépce's 1833 death, Daguerre continued to research the chemistry and mechanics of recording images by coating copper plates with iodized silver.[1] Early experiments required hours of exposure in the camera to produce visible results. In 1835 Daguerre discovered—after accidentally breaking a mercury thermometer, according to traditional accounts—a method of developing the faint or invisible images on plates that had been exposed for only 20 to 30 minutes.[1] Further refinement of his process would allow him to fix the image—preventing further darkening of the silver—using a strong solution of common salt. An 1837 still life of plaster casts, a wicker-covered bottle, a framed drawing and a curtain—titled L'Atelier de l'artiste—has been claimed to be the first daguerreotype to successfully undergo the full process of exposure, development and fixation.[1]

The French Academy of Sciences announced the daguerreotype process on January 9, 1839. Later that year William Fox Talbot announced his silver chloride "sensitive paper" process.[6] Together, these announcements mark 1839 as the year photography was born.[7] although Daguerre's view of the street outside his window was produced the year previously, 1838.

Daguerre did not patent and profit from his invention in the usual way. Instead, it was arranged that the French government would acquire the rights in exchange for a lifetime pension. The government would then present the daguerreotype process "free to the world" as a gift, which it did on August 19, 1839. However, on August 14, 1839, a patent agent acting on Daguerre's behalf filed for a patent in England. Consequently, Britain became the only nation in which the purchase of a license was legally required to make and sell daguerreotypes.[8]

François Arago noted that early attempts at photography, which required very long exposures, could not capture detail properly because of the movement of the sun, so that shadows came from different directions during the course of these long exposures.

Camera obscura

The camera obscura is a naturally occurring phenomenon. When a hole in the wall of a dark room faces onto a brightly lit scene—for example a dark cave on the edge of a sunlit valley—a picture of the scene outside can be projected upside-down onto a sheet of paper or parchment held at a suitable distance from the hole inside the dark room. Early camerae obscurae were large dark rooms of this type (camera obscura is Latin for dark chamber).[10][11] The system gives a brighter picture when the hole is replaced by a lens and portable camerae obscurae were built with an internal mirror at 45 degrees to make the image upright. They are fitted with a ground glass viewing screen and are used as a drawing aid by artists.

Daguerre would have been familiar with the camera obscura as a tool in his work as a theatrical scene painter and had developed a visual public entertainment called the Diorama. By painting on both sides of a piece of white cloth and illuminating the painting first from the front, then from the back, an illusion of movement could be obtained to depict a train crash, or the erupting of a volcano. Dioramas were opened in towns in several countries.

The Wolcott daguerreotype camera

The first US patent for photographic apparatus was Alexander Wolcott's daguerreotype camera that had a concave mirror instead of a lens on the principle of a reflecting telescope.[12][13] The concave mirror was fitted at one end of the camera, and focusing was done by adjusting the position of the plate in a holder that slides along a rail. This arrangement enabled more light to reach the plate than with the lenses of the time and the Woolcott camera became popular in the US.

Daylight studios

Establishments producing daguerreotype portraits generally had a daylight studio built on the roof, much like a greenhouse. Whereas artificial electric lighting later in the development of photography was done in a dark room building up the light with hard spotlights and softer floodlights, the daylight studio was equipped with screens and blinds to control the light to reduce it and make it unidirectional or diffusers to soften harsh direct sunlight. Blue filtration was sometimes used to make it easier for the sitter to withstand strong light and the daguerreotype plate is more sensitive to light at the blue end of the spectrum.

The process

Plate manufacture

The daguerreotype image is formed on a highly polished silver surface. Usually the silver is a thin layer on a copper substrate, but other metals such as brass can be used for the substrate and daguerreotypes can also be made on solid silver sheets. A surface of very pure silver is preferable, but sterling (92.5 percent pure) or US coin (90 percent pure) or even lower grades of silver are functional. In 19th century practice, the usual stock material, Sheffield plate, was produced by a process sometimes called plating by fusion. A sheet of sterling silver was heat-fused onto the top of a thick copper ingot. When the ingot was repeatedly rolled under pressure to produce thin sheets, the relative thicknesses of the two layers of metal remained constant. The alternative was to electroplate a layer of pure silver onto a bare copper sheet. The two technologies were sometimes combined, the Sheffield plate being given a finishing coat of pure silver by electroplating.

Polishing

Because the silver surface of the plate had to be completely free of tarnish or other contamination when it was sensitized, the daguerreotypist had to perform the final polishing and cleaning operation not too long before use. In the 19th century method of polishing, it was done with a buff covered with a hide or velvet, first using rotten stone, then jeweler's rouge, then lampblack. Finally, the surface was swabbed with nitric acid to burn off any residual organic matter.

Sensitization

In darkness or by the light of a safelight, the silver surface was exposed to halogen fumes. Originally, only iodine fumes (from iodine crystals at room temperature) were used, producing a surface coating of silver iodide, but it was soon found that a subsequent exposure to bromine fumes greatly increased the sensitivity of the silver halide coating. Exposure to chlorine fumes, or a combination of bromine and chlorine fumes, could also be used. A final re-fuming with iodine was typical.

Exposure

The plate was then carried to the camera in a light-tight plate holder. Withdrawing a protective dark slide or opening a pair of doors in the holder exposed the sensitized surface within the dark camera and removing a cap from the camera lens began the exposure, creating an invisible latent image on the plate. Depending on the sensitization chemistry used, the brightness of the lighting, and the light-concentrating power of the lens, the required exposure time ranged from a few seconds to many minutes.[14][15] After the exposure was judged to be complete, the lens was capped and the holder was again made light-tight and removed from the camera.

Development

The latent image was developed to visibility by several minutes of exposure to the fumes given off by heated mercury in a purpose-made developing box. The toxicity of mercury was well known in the 19th century, but precautionary measures were rarely taken.[16] Today, however, the hazards of contact with mercury and other chemicals traditionally used in the daguerreotype process are taken more seriously, as is the risk of release of those chemicals into the environment.[17][18][19]

In the Becquerel variation of the process, published in 1840 but very seldom used in the 19th century, the plate, sensitized by fuming with iodine alone, was developed by overall exposure to sunlight passing through yellow or red glass. The silver iodide in its unexposed condition was insensitive to the red end of the visible spectrum of light and was unaffected, but the latent image created in the camera by the blue, violet and ultraviolet rays color-sensitized each point on the plate proportionally, so that this color-filtered "sunbath" intensified it to full visibility, as if the plate had been exposed in the camera for hours or days to produce a visible image without development.

Fixing

After development, the light sensitivity of the plate was arrested by removing the remaining silver halide with a mild solution of sodium thiosulfate; Daguerre's initial method was to use a hot saturated solution of common salt.

Gilding

Also called gold toning, this addition to Daguerre's original process was introduced by Hippolyte Fizeau in 1840 and soon became part of the standard procedure. To give the steely gray image a slightly warmer tone and physically reinforce the powder-like silver particles of which it was composed, a gold chloride solution was pooled onto the surface and the plate was briefly heated over a flame, then drained, rinsed and dried. Without this treatment the image was as delicate as the "dust" on a butterfly's wing.

Sealing

Even if strengthened by gilding, the image surface was still very easily marred and the silver was subject to tarnishing from exposure to the air, so the finished plate was bound up with a protective cover glass to create a sealed enclosure. In the US and UK, a gilt brass mat was normally used to separate the image surface from the glass. In continental Europe, a thin cardboard mat or passepartout usually served that purpose and the border area of the cover glass was often reverse-painted black with concentric gold stripes around the image.

Casing and other display options

There were two main methods of finishing daguerreotypes for protection and display:

In the US and Britain, the tradition of preserving miniature paintings in a wooden case covered with leather or paper stamped with a relief pattern continued through to the daguerreotype. Some daguerreotypists were portrait artists who also offered miniature portraits. Black-lacquered cases ornamented with inset mother of pearl were sometimes used. The more substantial Union case was made from a mixture of colored sawdust and shellac (the main component of wood varnish) formed in a heated mold to produce a decorative sculptural relief. The word "Union" referred to the sawdust and varnish mixture — the manufacture of Union cases began in 1856. In all types of cases, the inside of the cover was lined with velvet or plush or satin to provide a dark surface to reflect into the plate for viewing and to protect the cover glass.[20] Some cases, however, held two daguerreotypes opposite each other. The cased images could be set out on a table or displayed on a mantelpiece. Most cases were small and lightweight enough to easily carry in a pocket, although that was not normally done.

The other approach, common in France and the rest of continental Europe, was to hang the daguerreotype on the wall in a frame, either simple or elaborate.[21] [22] Conservators were able to determine that a daguerreotype of Walt Whitman was made in New Orleans with the main clue being the type of frame, which was made for wall hanging in the French and continental style. Supporting evidence of the New Orleans origin was a scrap of paper from Le Mesager, a New Orleans bilingual newspaper of the time, which had been used to glue the plate into the frame.[23] Other clues used by historians to identify daguerreotypes are hallmarks in the silver plate and even the distinctive patterns left by different photographers when polishing the plate with a leather buff, which leaves extremely fine parallel lines discernible on the surface.[24]

As the daguerreotype itself is on a relatively thin sheet of soft metal, it was easily sheared down to sizes and shapes suited for mounting into lockets, as was done with miniature paintings.[25][26][27] Other imaginative uses of daguerreotype portraits were to mount them in watch fobs and watch cases, jewel caskets and other ornate silver or gold boxes, the handles of walking sticks, and in brooches, bracelets and other jewelry now referred to by collectors as daguerreian jewelry.[28] The cover glass or crystal was sealed either directly to the edges of the daguerreotype or to the opening of its receptacle and a protective hinged cover was usually provided.

Unusual characteristics

Daguerreotypes are normally laterally reversed — mirror images — because they are necessarily viewed from the side that originally faced the camera lens. Although a daguerreotypist could attach a mirror or reflective prism in front of the lens to obtain a right-reading result, in practice this was rarely done. The use of either type of attachment caused some light loss, somewhat increasing the required exposure time, and unless they were of very high optical quality they could degrade the quality of the image. Right-reading text or right-handed buttons on men's clothing in a daguerreotype may only be evidence that it is a copy of a typical wrong-reading original.

Copies and reproductions by lithography

Although daguerreotypes are unique images, they could be copied by re-daguerreotyping the original. Copies were also produced by lithography or engraving.[29] Today, they can be digitally scanned.

Beginnings of the age of photomechanical reproduction

Seen from the perspective of today, when developments in photography have been to increase image quality while reducing the skill and knowledge required by the camera operator, daguerreotypes are expensive and time consuming to produce. They are cumbersome and heavy if many images are to be stored in large quantities and they require a skilled operator. Long exposures that necessitated headrests resulted in a proliferation of stiff, rigid poses in most of the surviving daguerreotypes, with some notable exceptions.

However, when the process was introduced, it offered advantages over existing technologies. Illustrations in magazines up to then had been made by woodcuts or by etching or engraving on copper plates, by mezzotint or by lithography. Portraits were made by amateur and professional artists, but capturing a likeness was revolutionized with the advent of photography.

As an astronomical application in the 1870s

Commercial portraiture was only one aspect of the opening up of the age of mechanical reproduction. Arago had in his address to the House of Deputies outlined a wealth of possible applications including astronomy and the daguerreotype was used as the cutting edge technique in astronomical photography in the 1870s. Although the collodion wet plate process offered a cheaper and more convenient alternative for commercial portraiture and for other applications with shorter exposure times, when the transit of Venus was about to occur and observations were to be made from several sites on the earth's surface in order to calculate astronomical distances, daguerreotypy proved a more accurate method of making visual recordings through telescopes because it was a dry process with greater dimensional stability, whereas collodion glass plates were exposed wet and the image would move as the plate dried.

The invention of photography (photography and daguerreotypy were one and the same) made cataclysmic changes throughout society regarding what was illusion and what was reality. It is particularly significant that the first process to emerge and to be practiced widely was able to faithfully record fine detail at a resolution that most of today's digital cameras are not able to match (when compared with a well exposed and sharp large format daguerreotype). The process is unsurpassed for reproducing fine detail over a long tonal range and gives an illusion of reality unlike any other process.[30]

The surface of a daguerreotype is like a mirror, with the image made directly on the silver surface. It is very fragile and can be rubbed off with a finger. The finished plate also must be angled so as to reflect some dark surface for the image to be visible. Depending on the angle viewed and the color of the surface reflected into it, the image can change from a positive to a negative.[31] The viewer's own reflection will be seen at the same time.

The fragility of the image is a disadvantage because the daguerreotypist needs to buy in a stock of glass cassettes to house the daguerreotypes produced for clients but as the astronomer Arago pointed out in his presentation of the process to the French house of Deputies, the expense of the silver is offset by being able to wipe a plate clean and produce images again and again on the same plate.

Photographing people

At the time the process was introduced, daguerreotyping a brightly sunlit subject typically required about ten minutes of exposure, so the earliest daguerreotypes were of still lifes and landscapes. The oldest well-documented daguerreotype featuring human subjects is Daguerre's own 1838 view of the Boulevard du Temple, a busy street in Paris. The street appears deserted because the traffic (which would have been horse-drawn carriages) was moving and left no image; but a man having his shoes shined and the bootblack, are visible because they stayed in position long enough for their images to be recorded.[32]

Reduction of exposure time

The very first daguerreotypes used Chevalier lenses that were "slow", and the light sensitive material was silver iodide made by fuming the silver plate with iodine vapor. This meant that the exposure in the camera was too long to conveniently take portraits commercially and so the first subjects taken were immobile subjects such as street scenes, still life[33] architectural studies, etc.

Two changes were introduced that shortened the exposure times: one was fitting lenses of a larger diameter to the camera and the other was a modification to the chemistry used.[34]

When Petzval lenses[35] were introduced in 1841, with a larger effective aperture and the plate was sensitized not only with iodine but also with bromine and chlorine and forming light sensitive crystals of silver iodide, silver bromide and/or silver chloride that are more light-sensitive than silver iodide alone,[36] the exposures were reduced (the lens remaining uncapped for a shorter time), making commercial portraits viable. Increased speed was achieved using the same chemistry in the later silver processes that followed.[37] Usually, it was arranged so that the sitters leaned their elbows on a support such as a posing table whose height could be adjusted or else head rests were used that did not show in the picture and this led to most daguerreotype portraits having stiff, lifeless poses. Some exceptions exist with lively expressions full of character as photographers saw the potential of the new medium. These are represented in museum collections and are the most sought after by private collectors today.[38] Daguerreotypes were mounted in cases under glass with a cover, or in a frame that could be hung on a wall.[39] They were usually sealed with tape to reduce oxidization and tarnishing of the plate as well as mechanical damage from being touched.

The process was developed by Louis Daguerre together with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. Niépce had produced the first photographic image in the camera obscura with an eight-hour exposure using bitumen of Judea on a pewter plate developing it in lavender oil, a process he called heliography. [2] The bitumen hardened where light had affected it, while the non-exposed portions were washed away.

The image in a daguerreotype is often described as being formed by the amalgam, or alloy, of mercury and silver because mercury vapor from a pool of heated mercury is used to develop the plate; but using the Becquerel process (using a red filter and two-and-a-half stops extra exposure) daguerreotypes can be produced without mercury, and chemical analysis shows that there is no mercury in the final image with the Becquerel process. This brings into question the theory that the image is formed of amalgam with mercury development.[40]

Exposure times were reduced by sensitizing the plate with bromine and chlorine in addition to iodine, and by replacing the original Chevalier lens, which was best for photographing landscapes, with the larger-diameter "fast" portrait lens designed by Joseph Petzval. Voigtländer's small, all-metal Daguerrotype camera made possible an exposure time of as little as two seconds in bright sunlight, if the shadows were underexposed,[41][42] but his unusual design did not catch on and was not a commercial success.

Although the daguerreotype process could only produce a single image at a time, copies could be created by re-daguerreotyping the original,[43] although this proved difficult according to Joseph Maria Eder.[44] says that copying daguerreotypes in the camera was difficult, but good copies are to be found. As with any original photograph that is copied, the contrast increases. With a daguerreotype, any writing will appear back to front. Recopying a daguerreotype will make the writing appear normal and rings worn on the fingers will appear on the correct hand etc. Another device to make a daguerreotype the right way round would be to use a mirror when taking the photograph.

The daguerreotypes of the 1852 Omaha Indian (Native American) Delegation in the Smithsonian include a daguerrotype copied in the camera (figs 3 and 4 in the link) recognizable by the contrast being high and a black line down the side of the platel[45]

Proliferation

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri[46] and Jules Itier[47] in France, and Johann Baptist Isenring in Switzerland, became prominent daguerreotypists. In Britain, however, Richard Beard bought the British daguerreotype patent from Miles Berry in 1841 and closely controlled his investment, selling licenses throughout the country and prosecuting infringers.[48] Among others, Antoine Claudet[49] and Thomas Richard Williams[50] produced daguerreotypes in the UK.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Daguerreotype photography spread rapidly across the United States after the discovery first appeared in US newspapers in February 1839.[52][53] In the early 1840s, the invention was introduced in a period of months to practitioners in the United States by Samuel Morse,[54] inventor of the telegraph code. By 1853 an estimated three million daguerreotypes per year were being produced in the United States alone.[55] One of these original Morse Daguerreotype cameras is currently on display at the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, DC.[7] A flourishing market in portraiture sprang up, predominantly the work of itinerant practitioners who traveled from town to town. For the first time in history, people could obtain an exact likeness of themselves or their loved ones for a modest cost, making portrait photographs extremely popular with those of modest means. Celebrities and everyday people sought portraits and workers would save an entire day's income to have a daguerreotype taken of them, including occupational portraits.[56] Notable U.S. daguerreotypists of the mid-19th century included James Presley Ball,[57] Samuel Bemis,[58] Abraham Bogardus,[58] Mathew Brady,[59] Thomas Martin Easterly,[60] François Fleischbein, Jeremiah Gurney,[61] John Plumbe, Jr.,[62] Albert Southworth,[63] Augustus Washington,[64] Ezra Greenleaf Weld,[65] and John Adams Whipple.[58]

This method spread to other parts of the world as well. The first daguerreotype in Australia was taken in 1841, but no longer survives. The oldest surviving Australian daguerreotype is a portrait of Dr. William Bland taken in 1845.[66] In 1857, Ichiki Shirō created the first known Japanese photograph, a portrait of his daimyo Shimazu Nariakira. This photograph was designated an Important Cultural Property by the government of Japan.[citation needed]

Late and modern use

Although the daguerreotype process is usually said to have died out completely in the early 1860s, documentary evidence indicates that some very slight use of it persisted more or less continuously throughout the following 150 years of its supposed extinction.[67] A few first-generation daguerreotypists refused to entirely abandon their beautiful old medium when they started making the new, cheaper, easier to view but comparatively drab ambrotypes and tintypes.[68] Historically-minded photographers of subsequent generations, often fascinated by daguerreotypes, sometimes experimented with making their own or even revived the process commercially as a "retro" portraiture option for their clients.[69][70] These eccentric late uses were extremely unusual and surviving examples reliably dated to between the 1860s and the 1960s are now exceedingly rare.[71]

The daguerreotype experienced a minor renaissance in the late 20th century and the process is currently practiced by a handful of enthusiastic devotees; there are thought to be fewer than 100 worldwide (see list of artists on cdags.org in links below). In recent years artists like Jerry Spagnoli, Adam Fuss, Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand and Chuck Close have reintroduced the medium to the broader art world. The use of electronic flash in modern daguerreotypy has solved many of the problems connected with the slow speed of the process when using daylight.

International group exhibitions of contemporary daguerreotypists' works have been held, notably the 2009 exhibition in Bry Sur Marne, France, with 182 daguerreotypes by 44 artists, and the 2013 ImageObject exhibition in New York City, showcasing 75 works by 33 artists. The appeal of the medium lies in the "magic mirror" effect of light striking the polished silver plate and revealing a silvery image which can seem ghostly and ethereal even while being perfectly sharp, and in the dedication and handcrafting required to make a daguerreotype.

Gallery

-

Daguerreotype camera built by La Maison Susse Frères in 1839, with a lens by Charles Chevalier

-

The first authenticated image of Abraham Lincoln was this daguerreotype of him as U.S. Congressman-elect in 1846, attributed to Nicholas H. Shepard of Springfield, Illinois

-

Daguerreotype of Andrew Jackson at age 77 or 78 (1844 or 1845).

-

Daguerreotype of the Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington aged 74 or 75, made by Antoine Claudet in 1844.

-

Ichiki Shirō's 1857 daguerreotype of Shimazu Nariakira, the earliest surviving Japanese photograph

-

The solar eclipse of July 28, 1851 is the first correctly exposed photograph of a solar eclipse, using the daguerreotype process.

See also

Footnotes

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (July 2014) |

- ^ a b c d e f Stokstad, Marilyn; David Cateforis; Stephen Addiss (2005). Art History (Second ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. pp. 964–967. ISBN 0-13-145527-3.

- ^ Szabadváry, Ferenc (1992). History of analytical chemistry. Taylor & Francis. p. 17. ISBN 2-88124-569-2.

- ^ Susan Watt (2003). Silver. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-7614-1464-3. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

... But the first person to use this property to produce a photographic image was German physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze. In 1727, Schulze made a paste of silver nitrate and chalk, placed the mixture in a glass bottle and wrapped the bottle in ...

- ^ "The First Photograph - Heliography". Retrieved 2009-09-29.

from Helmut Gernsheim's article, "The 150th Anniversary of Photography," in History of Photography, Vol. I, No. 1, January 1977: ... In 1822, Niépce coated a glass plate ... The sunlight passing through ... This first permanent example ... was destroyed ... some years later.

- ^ Fragment > An Account of a method of copying Paintings upon glass, and of making Profiles, by the agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. WEDGWOOD, ESQ. With Observations by H. DAVY. (1802)

- ^ Note: Talbot's early "sensitive paper" or "photogenic drawing" process, which required very long camera exposures, should not be confused with the much more practical Calotype or Talbotype process, invented in 1840 and introduced in 1841.

- ^ a b "A Daguerreotype of Daguerre". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-07-17. Cite error: The named reference "NMAH" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Articles by R. Derek Wood on the history of the daguerreotype at "Midley History of early Photography".

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney P. Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries: All the Milestones in Ingenuity—From the Discovery of Fire to the Invention of the Microwave Oven. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004. ISBN 0-471-24410-4

- ^ The Magic Mirror of Life - An appreciation of the camera obscura Jack and Beverly Wilgus

- ^ Article by Philip Steadman about his book Vermeer's Camera Oxford University Press 2001

- ^ Woolcott daguerreotype camera

- ^ Historic camera

- ^ Writing on the 8th September 1841, Claudet gave his exposures as in June 10 to 20 seconds; in July, in 20 to 40 seconds and in September, in 60 to 90 seconds.

- ^ On a cloudy day, the exposure was given as three or four minutes.

- ^ S.D. Hummphrey, in The Daguerrian Journal vol IV (1852 p288 cited in Beaumont Newhall The Daguerreotype in America 3rd Revised Edition (New York: Dover Publications 1976) p. 126 cited in Kenneth E. Nelson The Cutting Edge of Yesterday

- ^ Andrew R. Barron The Myth, Reality and History of Mercury Toxicity

- ^ David A. Olson Mercury Toxicity

- ^ The proverbial phrase “mad as a hatter” refers to the strange behavior of poisoned hat makers who used mercury nitrate, a chemical which is readily absorbed through the skin, to soften and shape animal furs. Similar problems were met by the early photographers, who used vaporized mercury to create daguerreotypes. Biochemistry. 5th edition Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. New York: W H Freeman; 2002.

- ^ Daguerreotypecases

- ^ Antwerp Photography Museum

- ^ Wall preserver for daguerreotype. Princeton University

- ^ Recommended Citation Bethel, Denise B.. "Notes on an Early Daguerreotype of Walt Whitman."Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 9 (Winter 1992), 148-153. Available at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/wwqr/vol9/iss3/5

- ^ Daguerreobase

- ^ Daguerreotype locket

- ^ John Hannavy The Victorian Photographer at Work

- ^ Sixth-plate daguerreotype portrait of a man inserting daguerreotypes into lockets. On the table is an open locket awaiting its image.

- ^ The collection of Matthew R. Isenberg The Daguerreian Society

- ^ Paris et ses environs: reproduits par le daguerréotype sous la direction de M. Ch. Philipon

- ^ Julie Rehmeyer 1848 Daguerreotypes Bring Middle America's Past to Life Wired Magazine July 9, 2010

- ^ Includes a daguerreotype plate angled so as to appear as a negative

- ^ Easby, Rebecca Jeffrey. "Daguerre's Paris Boulevard". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/culturepicturegalleries/8898962/Louis-Daguerre-and-the-pioneers-of-photography.html

- ^ op.cit.

- ^ [1]

The Petzval Portrait Lens 1841 Department of Imaging and Printing Technology, Chulalongkorn University, Bankok, Thailand - ^ Op. cit.

- ^ [Eder History of Photography]

- ^ The Chess Players Daguerreotype Musée d'Orsay

- ^ Daguerreotype at Princeton University with nail holes in the brass preserver from being nailed to a wall

- ^ The Daguerreotype: nineteenth-century technology and modern science By M. Susan Barger, William Blaine White

- ^ Eder, Josef Maria History of Photography

- ^ Voigtländer Daguerreotype Camera. National Media Museum. UK.

- ^ Memory.loc.gov

- ^ Joseph Maria Eder History of Photography

- ^ A Preponderance of Evidence:The 1852 Omaha Indian Delegation Daguerreotypes Recovered The evidence for determining that figure 3 was a copy daguerreotype is the black line (edge of the copper plate) that appears very clearly in figure 4— directly above and to the right of the SCOVILL MFG CO. marking and that this daguerreotype was much higher in contrast than the other.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Jules Itier. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Wood, R. Derek. "The Daguerreotype in England: Some Primary Material Relating to Beard's Lawsuits." History of Photography, October 1979, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 305–09.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Antoine Claudet. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Thomas Richard Williams. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ "Early photography: making daguerreotypes". J. Paul Getty Museum with Khan Academy. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ "Chemical and Optical Discovery". The Pittsburgh Gazette. 28 February 1839. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Ewer, Gary W. (2011). "Texts from 1839". Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ "Collections | National Museum of American History". Americanhistory.si.edu. 2012-12-17. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ London, Barbara, Jim Stone, and John Upton. Photography. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2008.

- ^ "Occupational Portrait of Three Railroad Workers Standing on Crank Handcar". World Digital Library. 1850–1860. Retrieved 2013-07-16.

- ^ Cincinnati Historical Society Library. J. P. Ball, African American Photographer. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b c Newhall, Beaumont. The daguerreotype in America. 3rd rev. ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1976. ISBN 0-486-23322-7.

- ^ Leggat, Robert. A History of Photography from its Beginnings till the 1920s. Brady, Mathew. 1999. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Thomas Martin Easterly. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Jeremiah Gurney. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. John Plumbe, Jr. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes. Biographies. Albert S. Southworth. International Center of Photography and George Eastman House, 2005–2006. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ National Portrait Gallery. A Durable Memento. Portraits by Augustus Washington, African American Daguerreotypist. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum. Ezra Greenleaf Weld. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ Davies, Allan; State Library of New South Wales. "Photography in Australia". Celebrating 100 years of the Mitchell Library. Focus Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-875359-66-0.

- ^ Nelson, Kenneth E. (1996). "A Thumbnail History of the Daguerreotype"

- ^ Davis, D.T. (November 1896). "The Daguerreotype in America" McClure's Magazine 8(1):4-16. Near the end of the article, the author notes that the venerable Mr. Hawes, of Southworth and Hawes, has "a number of daguerreotypes made recently, for he is one of the few operators who remain loyal to the old process". Available online from the Daguerreian society

- ^ Tennant, John A. (August 1902). "Copying methods" The Photo-Miniature 4(41):201 et seq. See page 202 for mention of new daguerreotypes being made circa the 1890s by recycling old plates. (Selected text available online from The Daguerreian Society)

- ^ Cannon, Poppy. (June 1929). "An Old Art Revived" The Mentor 17(5):36–37 Available online from The Daguerreian Society

- ^ Romer, Grant B. (July 1977). "The Daguerreotype in America and England after 1860". History of Photography, 1(3):201 et seq.

Further reading

- Newhall, Beaumont The Daguerreotype in America ISBN 0486233227 ISBN 978-0486233222 Dover Publications.

- Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. L.J.M. Daguerre: the history of the diorama and the daguerreotype. New York: Dover Publications, 1968. ISBN 0-486-22290-X

- Barger, Susan M and White, William B. The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-Century Technology and Modern Science Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991

- Rudisill, Richard. Mirror image: the influence of the daguerreotype on American society. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971.

- Coe, Brian. The birth of photography: the story of the formative years, 1800–1900. London: Ash & Grant, 1976. ISBN 0-904069-06-0.

- Sobieszek, Robert A., Odette M. Appel-Heyne, and Charles R Moore. The spirit of fact: the daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes, 1843–1862. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1976. ISBN 0-87923-179-3

- Pfister, Harold Francis. Facing the light: historic American portrait daguerreotypes: an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, September 22, 1978 – January 15, 1979. Washington, D.C.: Published for the National Portrait Gallery by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1978.

- Richter, Stefan. The art of the daguerreotype. London: Viking, 1989. ISBN 0-670-82688-X.

- Barger, M Susan, and William B White. The daguerreotype: nineteenth-century technology and modern science. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87474-348-6

- Wood, John. America and the daguerreotype. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87745-334-9.

- Wood, John. The scenic daguerreotype: Romanticism and early photography. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1995. ISBN 0-87745-511-2.

- Lowry, Bates, and Isabel Lowry. The silver canvas: daguerreotype masterpieces from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: The Museum, 1998. ISBN 0-89236-368-1.

- Davis, Keith F., Jane Lee Aspinwall, and Marc F. Wilson. The origins of American photography: from daguerreotype to dry-plate, 1839–1885. Kansas City, MO: Hall Family Foundation, 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-12286-2.

- Kenney, Adele. Photographic Cases Victorian Design Sources 1840–1870, 2001 ISBN 0-7643-1267-7.

- Hannavy, John. Case Histories: The Packaging and Presentation of the Photographic Portrait in Victorian Britain 1840-1875, 2005. ISBN 1-85149-481-2.

External links

- Historique et description des procédés du daguerréotype rédigés par Daguérre, ornés du portrait de l'auteur, et augmentés de notes et d'observations par MM Lerebours et Susse Frères, Lerebours, Opticien de L'Observatoire; Susse Frères, Éditeurs. Paris 1839 (French)

- R. Derek WOOD, A State Pension for L. J. M. Daguerre for the secret of his daguerreotype technique Published in the quarterly journal Annals of Science September 1997 (Vol 54, No.5, pp. 489–506)

- [http://blog.eastmanhouse.org/2012/06/05/photographic-process-1-0-the-daguerreotype WATCH: George Eastman House "The Daguerreotype – Photographic Processes

- The J. Paul Getty Museum Early Photography: Making Daguerreotypes video

- Musée Orsay Daguerreotype Collection - under heading Overview click on Index of Works and search DAGUERREOTYPE

- Hill, Levi L. A Treatise on the Daguerreotype. The Whole Art Made Easy. 1850

- The Daguerreotype Process. Sussex PhotoHistory.

- Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography. Malcolm Daniel, Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Daguerreian Age in France 1839–1855. Malcolm Daniel. Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- *Xiaoqing Tang, Paul A. Ardis, Ross Messing, Christopher M. Brown, Randal C. Nelson, Patrick Ravines, and Ralph Wiegandt. University of Rochester, Rochester Digital analysis and restoration of daguerreotypes University of Rochester

- The Nanotechnology of the Daguerreotype University of Rochester on YouTube

- Cincinnati Waterfront Panorama Daguerreotype University of Rochester

- International Contemporary Daguerreotypes community (non profit org)

- The Daguerreian Society: History, and predominantly US oriented database & galleries

- The Daguerreotype: an Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera

- Daguerreotype Portraits and Views, 1836–1864: US Library of Congress

- The American Handbook of the Daguerreotype from Project Gutenberg

- The Social Construction of the American Daguerreotype Portrait

- 19th Century New Orleans Photography

- Photography, Old & New Again by John Fleischman and Robert Kunzig from Discover Magazine Article on Daguerreotypes and Holograms

- A University of Utah Podcast on Daguerreotype Theories

- Daguerreotype Plate Sizes

- Library of Congress Collection

- Photos The Boston Public Library's Cased Photo Collection on Flickr.com

- Daguerreotype collection at the Canadian Centre for Architecture

- First mention of the use of bromine in daguerreotypy

- The first photograph

- Auction of daguerreotype camera made by Daguerre's brother-in-law, Alphonse Giroux, Sociedad Ibero-Americana de la Historia de la Fotografia Museo Fotográfico y Archivo Historico "Adolfo Alexander"

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from July 2013

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from September 2013

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Articles with ibid from July 2014

- 1837 introductions

- 19th century in art

- Photographic processes dating from the 19th century

- Alternative photographic processes

- World Digital Library related

- Black and white photography