Anorexia nervosa: Difference between revisions

m removed extra comma |

|||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

Symptoms of a person with anorexia nervosa may include: |

Symptoms of a person with anorexia nervosa may include: |

||

* Refusal to maintain a normal [[body mass index]] for their age<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline"/> |

* Refusal to maintain a normal [[body mass index]] for their age, to maintain weight or regain lost weight.<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline"/> |

||

* [[Amenorrhoea|Amenorrhea]], a symptom that occurs after prolonged weight loss; causes menses to stop, hair becomes brittle, and skin becomes yellow and unhealthy<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline">{{cite journal | author = Attia E, Walsh BT | title = Anorexia Nervosa | journal = American Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 164 | issue = 12 | pages = 1805–1810 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18056234 | doi = 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071151 }}</ref> |

* [[Amenorrhoea|Amenorrhea]], a symptom that occurs after prolonged weight loss; causes menses to stop, hair becomes brittle, and skin becomes yellow and unhealthy<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline">{{cite journal | author = Attia E, Walsh BT | title = Anorexia Nervosa | journal = American Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 164 | issue = 12 | pages = 1805–1810 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18056234 | doi = 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071151 }}</ref> May not effect women on birth control <ref>http://www.dsm5.org/documents/eating%20disorders%20fact%20sheet.pdf</ref> |

||

* Fearful of even the slightest weight gain and takes all precautionary measures to avoid weight gain and becoming overweight<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline" /> |

* Fearful of even the slightest weight gain and takes all precautionary measures to avoid weight gain and becoming overweight<ref name="ajp.psychiatryonline" /> |

||

* Obvious, rapid, dramatic [[weight loss]] ''at least'' 15% under normal body weight<ref>{{cite web|title=Anorexia Nervosa|url=http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/|publisher=National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders|accessdate=15 April 2014}}</ref> |

* Obvious, rapid, dramatic [[weight loss]] ''at least'' 15% under normal body weight<ref>{{cite web|title=Anorexia Nervosa|url=http://www.anad.org/get-information/get-informationanorexia-nervosa/|publisher=National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders|accessdate=15 April 2014}}</ref> |

||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

* Thin appearance including emaciation, may not have visible weight loss <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* [[fixation (psychology)|Obsession]] with [[food energy|calories]] and [[fat]] content of food |

|||

* Refusal to eat and denial of hunger <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref>, includes excuse for lack of hunger, sickness, use stomach, nervous, anxious, planning of eating later |

|||

* [[fixation (psychology)|Obsession]] with [[food energy|calories]] and [[fat]] content of food. Can include fixation on 'health' and 'good' and 'bad' foods. Definition of 'good' foods may be so limited that malnutrition occurs or individuals would rather not eat than eat something less nutritious. |

|||

* Eliminating food groups: fats, carbs, sugars, proteins <ref>http://eating-disorders.org.uk/information/the-effects-of-under-eating/</ref> |

|||

* Preoccupation with [[food]], [[recipes]], or [[cooking]]; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves<ref>{{cite journal | author = Pietrowsky R, Krug R, Fehm HL, Born J | title = Food deprivation fails to affect preoccupation with thoughts of food in anorexic patients | journal = The British Journal of Clinical Psychology | volume = 41 | issue = Pt 3 | pages = 321–6 | year = 2002 | pmid = 12396259 | doi = 10.1348/014466502760379172 }}</ref> |

* Preoccupation with [[food]], [[recipes]], or [[cooking]]; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves<ref>{{cite journal | author = Pietrowsky R, Krug R, Fehm HL, Born J | title = Food deprivation fails to affect preoccupation with thoughts of food in anorexic patients | journal = The British Journal of Clinical Psychology | volume = 41 | issue = Pt 3 | pages = 321–6 | year = 2002 | pmid = 12396259 | doi = 10.1348/014466502760379172 }}</ref> |

||

* Food restriction despite being [[underweight]] |

* Food restriction despite being [[underweight]] |

||

* Dehydration, a large portion of our daily liquids come from food <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* Low electrolytes from drinking too much <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat around others, or hiding or discarding food |

* Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat around others, or hiding or discarding food |

||

* Eating around others and severely restricting food intake in private |

|||

* Loss of hunger, may be psychological or physical in nature. Sometimes caused by hormone depletion. Decreased Leptin levels can result in weight destabilization and how your brain tells your body to start and stop eating or how to burn fat.<ref>http://www.webmd.boots.com/mental-health/anorexia-what-anorexia-can-do-to-your-body</ref> |

|||

* Purging: May use [[laxatives]], [[diet pills]], [[ipecac syrup]], or [[water pills]]; may engage in self-induced [[vomiting]]; may run to the bathroom after eating in order to vomit and quickly get rid of ingested calories<ref>{{cite journal | author = Kovacs D, Palmer RL | title = The associations between laxative abuse and other symptoms among adults with anorexia nervosa | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 36 | issue = 2 | pages = 224–8 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15282693 | doi = 10.1002/eat.20024 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Friedman EJ | title = Death from ipecac intoxication in a patient with anorexia nervosa | journal = The American Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 141 | issue = 5 | pages = 702–3 | year = 1984 | pmid = 6143508 }}</ref> (see also [[bulimia nervosa]]) |

* Purging: May use [[laxatives]], [[diet pills]], [[ipecac syrup]], or [[water pills]]; may engage in self-induced [[vomiting]]; may run to the bathroom after eating in order to vomit and quickly get rid of ingested calories<ref>{{cite journal | author = Kovacs D, Palmer RL | title = The associations between laxative abuse and other symptoms among adults with anorexia nervosa | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 36 | issue = 2 | pages = 224–8 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15282693 | doi = 10.1002/eat.20024 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Friedman EJ | title = Death from ipecac intoxication in a patient with anorexia nervosa | journal = The American Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 141 | issue = 5 | pages = 702–3 | year = 1984 | pmid = 6143508 }}</ref> (see also [[bulimia nervosa]]) |

||

* May engage in frequent, strenuous, or compulsive [[exercise]]<ref>{{cite journal | author = Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G | title = Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 31 | issue = 4 | pages = 370–5 | year = 2002 | pmid = 11948642 | doi = 10.1002/eat.10042 }}</ref> |

* May engage in frequent, strenuous, or compulsive [[exercise]]<ref>{{cite journal | author = Peñas-Lledó E, Vaz Leal FJ, Waller G | title = Excessive exercise in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: relation to eating characteristics and general psychopathology | journal = The International Journal of Eating Disorders | volume = 31 | issue = 4 | pages = 370–5 | year = 2002 | pmid = 11948642 | doi = 10.1002/eat.10042 }}</ref> |

||

* Hypoglycemia or low blood sugar, feelings of fainting <ref>http://www.webmd.boots.com/mental-health/anorexia-what-anorexia-can-do-to-your-body</ref> |

|||

* [[Image Orientation]] and seeming preoccupation with aesthetics including clothing or hair. Fixation on types of clothes they will wear, taking the perfect self portrait, posting very thin social media selfies, wearing revealing clothing to exhibit size |

|||

* Preoccupation with social acceptance (from friends, family, coworkers, significant other), may include desire to act or dress a certain way, meet image demands or demands for time and energy (work over time, volunteer, conform). |

|||

* Secretive behaviors including hiding food, eating and toilet habits or binding and purging actions, wearing baggy clothing to cover weight loss (anorexics may hide or display weight loss depending on motivations) |

|||

* [[Perception]] of self as overweight despite being told by others they are too thin |

* [[Perception]] of self as overweight despite being told by others they are too thin |

||

* Intolerance to cold and frequent complaints of being cold; body temperature may lower ([[hypothermia]]) in an effort to conserve energy<ref>{{cite journal | author = Haller E | title = Eating disorders. A review and update | journal = The Western Journal of Medicine | volume = 157 | issue = 6 | pages = 658–62 | year = 1992 | pmid = 1475950 | pmc = 1022101 }}</ref> |

* Intolerance to cold and frequent complaints of being cold; body temperature may lower ([[hypothermia]]) in an effort to conserve energy<ref>{{cite journal | author = Haller E | title = Eating disorders. A review and update | journal = The Western Journal of Medicine | volume = 157 | issue = 6 | pages = 658–62 | year = 1992 | pmid = 1475950 | pmc = 1022101 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 120: | Line 131: | ||

* [[Bradycardia]] or [[tachycardia]] |

* [[Bradycardia]] or [[tachycardia]] |

||

* [[Depression (mood)|Depression]]: may frequently be in a sad, [[lethargic]] state<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lucka I | title = [Depression syndromes in patients suffering from anorexia nervosa] | language = Polish | journal = Psychiatria Polska | volume = 38 | issue = 4 | pages = 621–9 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15518310 }}</ref> |

* [[Depression (mood)|Depression]]: may frequently be in a sad, [[lethargic]] state<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lucka I | title = [Depression syndromes in patients suffering from anorexia nervosa] | language = Polish | journal = Psychiatria Polska | volume = 38 | issue = 4 | pages = 621–9 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15518310 }}</ref> |

||

* [[Solitude]]: may avoid friends and family; becomes withdrawn and secretive |

* [[Solitude]]: may avoid friends and family; becomes withdrawn and secretive, unwilling to discuss the disorder. May include loss of friends. |

||

* [[Cheeks]] may become swollen because of enlargement of the [[salivary gland]]s caused by excessive vomiting<ref>{{cite journal | author = Bozzato A, Burger P, Zenk J, Uter W, Iro H | title = Salivary gland biometry in female patients with eating disorders | journal = European Archives of Oto-rhino-laryngology | volume = 265 | issue = 9 | pages = 1095–102 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18253742 | doi = 10.1007/s00405-008-0598-8 }}</ref> |

* [[Cheeks]] may become swollen because of enlargement of the [[salivary gland]]s caused by excessive vomiting<ref>{{cite journal | author = Bozzato A, Burger P, Zenk J, Uter W, Iro H | title = Salivary gland biometry in female patients with eating disorders | journal = European Archives of Oto-rhino-laryngology | volume = 265 | issue = 9 | pages = 1095–102 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18253742 | doi = 10.1007/s00405-008-0598-8 }}</ref> |

||

* Swollen [[joints]]<ref>{{cite web|title=Signs of Anorexia|url=http://anorexia.emedtv.com/anorexia/signs-of-anorexia.html|work=anorexia.emedtv.com}}</ref> |

* Swollen [[joints]]<ref>{{cite web|title=Signs of Anorexia|url=http://anorexia.emedtv.com/anorexia/signs-of-anorexia.html|work=anorexia.emedtv.com}}</ref> |

||

* [[Abdominal distension]] |

* [[Abdominal distension]] or seeming weight around the midsection in relation to the rest of the body. |

||

* [[Halitosis]] (from vomiting or starvation-induced [[ketosis]]) |

* [[Halitosis]] (from vomiting or starvation-induced [[ketosis]]) |

||

* Dental discoloration, from vomiting or from insufficient food intake to remove the stains caused by dark liquids, especially tea and coffee |

|||

* Dry hair and skin, as well as hair thinning<ref>{{cite web|title=Noticing the Signs and Symptoms|url=http://www.something-fishy.org/isf/signssymptoms.php|work=The Something Fishy Website on Eating Disorders}}</ref><ref>[http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa National Eating Disorders Association]</ref> |

* Dry hair and skin, as well as hair thinning<ref>{{cite web|title=Noticing the Signs and Symptoms|url=http://www.something-fishy.org/isf/signssymptoms.php|work=The Something Fishy Website on Eating Disorders}}</ref><ref>[http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/anorexia-nervosa National Eating Disorders Association]</ref> |

||

* Fatigue<ref>{{cite journal|last=McClure|first=G.M.|author2=Timimi, Westman|title=Anorexia nervosa in early adolescence following illness — the importance of the sick role|journal=Journal of Adolescence|year=1995|volume=18|issue=3|page=359|doi=10.1006/jado.1995.1025}}</ref> |

* Fatigue<ref>{{cite journal|last=McClure|first=G.M.|author2=Timimi, Westman|title=Anorexia nervosa in early adolescence following illness — the importance of the sick role|journal=Journal of Adolescence|year=1995|volume=18|issue=3|page=359|doi=10.1006/jado.1995.1025}}</ref> |

||

* Digestive issues, stomach pains, constipation, diarrhea (made worse by laxatives and purging) <ref>http://www.webmd.boots.com/mental-health/anorexia-what-anorexia-can-do-to-your-body</ref> |

|||

* Low blood pressure <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* Irregular heart rhythms <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* Trouble sleeping, bags under eyes <ref>http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/eating-disorders/basics/symptoms/con-20033575</ref> |

|||

* Rapid mood swings |

* Rapid mood swings |

||

*Absence of [[menses]] |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:75%;" |

{| class="wikitable" style="width:75%;" |

||

Revision as of 12:20, 20 November 2014

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help).

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Anorexia nervosa | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by immoderate food restriction, inappropriate eating habits or rituals, obsession with having a thin figure, and an irrational fear of weight gain, as well as a distorted body self-perception. It typically involves excessive weight loss and is diagnosed approximately nine times more often in females than in males.[1] Due to their fear of gaining weight, individuals with this disorder restrict the amount of food they consume. Outside of medical literature, the terms anorexia nervosa and anorexia are often used interchangeably; however, anorexia is simply a medical term for lack of appetite and the majority of individuals afflicted with anorexia nervosa do not, in fact, lose their appetites.[2] Patients with anorexia nervosa often experience dizziness, headaches, drowsiness, fever, and a lack of energy. To counteract these side effects, particularly the latter, individuals with anorexia may engage in other harmful behaviors, such as smoking, excessive caffeine consumption, and excessive use of diet pills, along with an increased exercise regimen.

Anorexia nervosa is often coupled with a distorted self image[3][4] which may be maintained by various cognitive biases[5] that alter how the affected individual evaluates and thinks about their body, food, and eating.[6] People with anorexia nervosa often view themselves as overweight or "big" even when they are already underweight.[7]

Anorexia nervosa most often has its onset in adolescence and is more prevalent among adolescent females than adolescent males. In general, men appear to be more comfortable with their weight and perceive less pressure to be thin than women.[8] [9]

While the majority of people with anorexia nervosa continue to feel hunger, they deny themselves all but very small quantities of food.[6] The caloric intake of people with anorexia nervosa can vary significantly between individuals and over time, depending on whether they engage in binging and/or purging behavior.[10] Extreme cases of complete self-starvation are known. It is a serious health condition with a high incidence of comorbidity and similarly high mortality rate to serious psychiatric disorders.[7] People with anorexia have extremely high levels of ghrelin (the hunger hormone that signals a physiological need for food) in their blood.[citation needed] The high levels of ghrelin suggests[original research?] that their bodies are desperately trying to make them hungry[citation needed]; however, that hunger call is being suppressed, ignored, or overridden.[citation needed] Sufferers may commonly engage in self-harm behaviors in order to override their feelings of hunger.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Psychological

Not only does starvation result in physical complications, but mental complications as well.[11] P. Sodersten and colleagues suggest that effective treatment of this disorder depends on re-establishing reinforcement for normal eating behaviours instead of unhealthy weight loss.[2]

Anorexia nervosa is classified as an Axis I[12] disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-V), published by the American Psychiatric Association. The DSM-V should not be used by laypersons to diagnose themselves.

The DSM-V has replaced the previously used volume DSM-IV-TR, and in the new DSM-V there have been several changes made to the criteria for anorexia nervosa, most notably that of the amenorrhea criterion being removed. However, significant changes in wording have also been made to each remaining criterion.

DSM-5 Criteria

- Persistent restriction of energy intake leading to significantly low body weight (in context of what is minimally expected for age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health).

- Either an intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain (even though significantly low in weight).

- Disturbance in the way one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body shape and weight on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight.[13]

Subtypes:

- Restricting type: Individual does not utilize binge eating nor displays purging behavior as their main strategy for weight loss. Instead, the individual uses restricting food intake, fasting, diet pills, and/or exercise as a means for losing weight.[14]

- Binge-eating/purging type: Individual utilizes binge eating or displays purging behavior as a means for losing weight.[14]

Levels of Severity:

Body mass index (BMI) is used by the DSM-V as an indicator of the level of severity of anorexia nervosa. The DSM-V states these as follows:

- Mild: BMI of 17-17.99

- Moderate: BMI of 16-16.99

- Severe: BMI of 15-15.99

- Extreme: BMI of less than 15

ICD-10 Criteria

F 50.0: A disorder characterized by deliberate weight loss, induced and sustained by the patient. It occurs most commonly in adolescent girls and young women, but adolescent boys and young men may also be affected, as may children approaching puberty and older women up to the menopause. The disorder is associated with a specific psychopathology whereby a dread of fatness and flabbiness of body contour persists as an intrusive overvalued idea, and the patients impose a low weight threshold on themselves. There is usually undernutrition of varying severity with secondary endocrine and metabolic changes and disturbances of bodily function. The symptoms include restricted dietary choice, excessive exercise, induced vomiting and purgation, and use of appetite suppressants and diuretics.[15]

Medical

The initial diagnosis should be made by a competent medical professional. There are multiple medical conditions, such as viral or bacterial infections, hormonal imbalances, neurodegenerative diseases and brain tumors which may mimic psychiatric disorders including anorexia nervosa.

Medical Tests

Medical tests to check for signs of physical deterioration in anorexia nervosa may be performed by a general physician or psychiatrist. These are done as each doctor deems necessary. Some of the medical testing possibilities include the following:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): a test of the white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets used to assess the presence of various disorders such as leukocytosis, leukopenia, thrombocytosis and anemia which may result from malnutrition.[16]

- Urinalysis: a variety of tests performed on the urine used in the diagnosis of medical disorders, to test for substance abuse, and as an indicator of overall health[17]

- ELISA: Various subtypes of ELISA used to test for antibodies to various viruses and bacteria such as Borrelia burgdoferi (Lyme Disease)[18]

- Western Blot Analysis: Used to confirm the preliminary results of the ELISA[19]

- Chem-20: Chem-20 also known as SMA-20 a group of twenty separate chemical tests performed on blood serum. Tests include cholesterol, protein and electrolytes such as potassium, chlorine and sodium and tests specific to liver and kidney function.[20]

- Glucose tolerance test: Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) used to assess the body's ability to metabolize glucose. Can be useful in detecting various disorders such as diabetes, an insulinoma, Cushing's Syndrome, hypoglycemia and polycystic ovary syndrome[21][22]

- Secritin-CCK Test: Used to assess function of the pancreas and gall bladder[23][24]

- Serum cholinesterase test: a test of liver enzymes (acetylcholinesterase and pseudocholinesterase) useful as a test of liver function and to assess the effects of malnutrition[25]

- Liver Function Test: A series of tests used to assess liver function some of the tests are also used in the assessment of malnutrition, protein deficiency, kidney function, bleeding disorders, and Crohn's Disease.[26]

- Lh response to GnRH: Luteinizing hormone (Lh) response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH): Tests the pituitary glands' response to GnRh a hormone produced in the hypothalamus. Central hypogonadism is often seen in anorexia nervosa cases.[27]

- Creatine Kinase Test (CK-Test): measures the circulating blood levels of creatine kinase an enzyme found in the heart (CK-MB), brain (CK-BB) and skeletal muscle (CK-MM).[28][29]

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test: urea nitrogen is the byproduct of protein metabolism first formed in the liver then removed from the body by the kidneys. The BUN test is primarily used to test kidney function. A low BUN level may indicate the effects of malnutrition.[30]

- BUN-to-creatinine ratio: A BUN to creatinine ratio is used to predict various conditions. A high BUN/creatinine ratio can occur in severe hydration, acute kidney failure, congestive heart failure, and intestinal bleeding. A low BUN/creatinine ratio can indicate a low protein diet, celiac disease, rhabdomyolysis, or cirrhosis of the liver.[31][32][33]

- Electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG): measures electrical activity of the heart. It can be used to detect various disorders such as hyperkalemia[34]

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): measures the electrical activity of the brain. It can be used to detect abnormalities such as those associated with pituitary tumors[35][36]

- Upper GI Series: test used to assess gastrointestinal problems of the middle and upper intestinal tract[37]

- Thyroid Screen TSH, t4, t3 :test used to assess thyroid functioning by checking levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3)[38]

- Parathyroid hormone (PTH) test: tests the functioning of the parathyroid by measuring the amount of (PTH) in the blood. It is used to diagnose parahypothyroidism. PTH also controls the levels of calcium and phosphorus in the blood (homeostasis).[39]

- Barium enema: an x-ray examination of the lower gastrointestinal tract[40]

Signs and symptoms

Please note that not all individuals with anorexia nervosa exhibit the same symptoms, nor are all of these symptoms are required to be diagnosed with anorexia. Please consult the Diagnosis section for more detail.

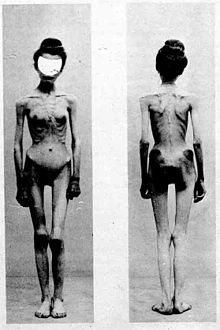

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder that is characterized by attempts to lose weight, to the point of self-starvation. A person with anorexia nervosa may exhibit a number of signs and symptoms, the type and severity of which may vary in each case and may be present but not readily apparent. Anorexia nervosa, and the associated malnutrition that results from self-imposed starvation, can cause severe complications in every major organ system in the body.[41][42][43]

Hypokalaemia, a drop in the level of potassium in the blood, is a sign of anorexia nervosa. A significant drop in potassium can cause abnormal heart rhythms, constipation, fatigue, muscle damage and paralysis.

Between 50% and 75% of individuals with an eating disorder experience depression. In addition, one in every four individuals who are diagnosed with anorexia nervosa also exhibit obsessive-compulsive disorder.[44]

Symptoms of a person with anorexia nervosa may include:

- Refusal to maintain a normal body mass index for their age, to maintain weight or regain lost weight.[45]

- Amenorrhea, a symptom that occurs after prolonged weight loss; causes menses to stop, hair becomes brittle, and skin becomes yellow and unhealthy[45] May not effect women on birth control [46]

- Fearful of even the slightest weight gain and takes all precautionary measures to avoid weight gain and becoming overweight[45]

- Obvious, rapid, dramatic weight loss at least 15% under normal body weight[47]

- Lanugo: soft, fine hair growing on the face and body[48] – one theory is that this is related to hypothyroidism, as there are several reports of a similar hypertrichosis occurring in hypothyroidism[49][50]

- Thin appearance including emaciation, may not have visible weight loss [51]

- Refusal to eat and denial of hunger [52], includes excuse for lack of hunger, sickness, use stomach, nervous, anxious, planning of eating later

- Obsession with calories and fat content of food. Can include fixation on 'health' and 'good' and 'bad' foods. Definition of 'good' foods may be so limited that malnutrition occurs or individuals would rather not eat than eat something less nutritious.

- Eliminating food groups: fats, carbs, sugars, proteins [53]

- Preoccupation with food, recipes, or cooking; may cook elaborate dinners for others, but not eat the food themselves[54]

- Food restriction despite being underweight

- Dehydration, a large portion of our daily liquids come from food [55]

- Low electrolytes from drinking too much [56]

- Food rituals, such as cutting food into tiny pieces, refusing to eat around others, or hiding or discarding food

- Eating around others and severely restricting food intake in private

- Loss of hunger, may be psychological or physical in nature. Sometimes caused by hormone depletion. Decreased Leptin levels can result in weight destabilization and how your brain tells your body to start and stop eating or how to burn fat.[57]

- Purging: May use laxatives, diet pills, ipecac syrup, or water pills; may engage in self-induced vomiting; may run to the bathroom after eating in order to vomit and quickly get rid of ingested calories[58][59] (see also bulimia nervosa)

- May engage in frequent, strenuous, or compulsive exercise[60]

- Hypoglycemia or low blood sugar, feelings of fainting [61]

- Image Orientation and seeming preoccupation with aesthetics including clothing or hair. Fixation on types of clothes they will wear, taking the perfect self portrait, posting very thin social media selfies, wearing revealing clothing to exhibit size

- Preoccupation with social acceptance (from friends, family, coworkers, significant other), may include desire to act or dress a certain way, meet image demands or demands for time and energy (work over time, volunteer, conform).

- Secretive behaviors including hiding food, eating and toilet habits or binding and purging actions, wearing baggy clothing to cover weight loss (anorexics may hide or display weight loss depending on motivations)

- Perception of self as overweight despite being told by others they are too thin

- Intolerance to cold and frequent complaints of being cold; body temperature may lower (hypothermia) in an effort to conserve energy[62]

- Hypotension and/or orthostatic hypotension

- Bradycardia or tachycardia

- Depression: may frequently be in a sad, lethargic state[63]

- Solitude: may avoid friends and family; becomes withdrawn and secretive, unwilling to discuss the disorder. May include loss of friends.

- Cheeks may become swollen because of enlargement of the salivary glands caused by excessive vomiting[64]

- Swollen joints[65]

- Abdominal distension or seeming weight around the midsection in relation to the rest of the body.

- Halitosis (from vomiting or starvation-induced ketosis)

- Dental discoloration, from vomiting or from insufficient food intake to remove the stains caused by dark liquids, especially tea and coffee

- Dry hair and skin, as well as hair thinning[66][67]

- Fatigue[68]

- Digestive issues, stomach pains, constipation, diarrhea (made worse by laxatives and purging) [69]

- Low blood pressure [70]

- Irregular heart rhythms [71]

- Trouble sleeping, bags under eyes [72]

- Rapid mood swings

| constipation[74] | diarrhea[75] | electrolyte imbalance[76] | cavities[77] | tooth loss[78] |

| cardiac arrest[79] | amenorrhoea[80] | edema[81] | osteoporosis[82] | osteopenia[83] |

| hyponatremia[84] | hypokalemia[85] | optic neuropathy[86] | brain atrophy[87][88] | leukopenia[89][90] |

The prevalent symptoms for anorexia nervosa (as discussed above) such as decreased body temperature, obsessive-compulsivity, and changes in psychological state, can actually be attributed to symptoms of starvation. This theory can be supported by a study by Routtenberg in 1968 involving rats who were deprived of food; these rats showed dramatic increases in their activity on the wheel in their cage at times when not being fed.[91] These findings could explain why those with anorexia nervosa are often seen excessively exercising; their overactivity is the result of fasting, and by increasing their activity they could raise their body temperature, increase their chances of stumbling upon food, or become distracted from their desire for nourishment (because they do not, in fact, lose their appetite). While it is commonly believed that those with AN do not have a normal appetite, this is not the case. Those with AN are typically obsessive about food, cooking often for others, but not eating the food themselves. Despite the fact that the physiological cause behind each case of anorexia nervosa is different, the most common theme seen across the board is the element of self-control. The underlying cause behind the disorder is rarely about the food itself; it is about the individual attempting to gain complete control over an aspect of their lives, in order to prove themselves, and distract them from another aspect of their lives they wish they could control. For example, a child with a destructive family life who restricts food intake in order to compensate for the chaos occurring at home.[91]

Complications

Anorexia nervosa can have serious implications if its duration and severity are significant and if onset occurs before the completion of growth, pubertal maturation, or the attainment of peak bone mass.[92] Complications specific to adolescents and children with anorexia nervosa can include the following:

- Growth retardation – height gain may slow and can stop completely with severe weight loss or chronic malnutrition. In such cases, provided that growth potential is preserved, height increase can resume and reach full potential after normal intake is resumed.[92] Height potential is normally preserved if the duration and severity of illness are not significant and/or if the illness is accompanied with delayed bone age (especially prior to a bone age of approximately 15 years), as hypogonadism may negate the deleterious effects of undernutrition on stature by allowing for a longer duration of growth compared to controls.[93] In such cases, appropriate early treatment can preserve height potential and may even help to increase it in some post-anorexic subjects due to the aforementioned reasons in addition to factors such as long-term reduced estrogen-producing adipose tissue levels compared to premorbid levels.[94][95][96][97]

- Pubertal delay or arrest – both height gain and pubertal development are dependent on the release of growth hormone and gonadotrophins (LH and FSH) from the pituitary gland. Suppression of gonadotrophins in patients with anorexia nervosa has frequently been documented.[92] However, a study demonstrated that growth hormone levels were not a predictor of height measures in anorexic patients, which is suggestive of a resistance to growth hormone effects at the growth plate, similar to the resistance to growth hormone of bone-formation markers.[93] Instead, insulin-like growth factor had a larger effect, with lower IGF-I levels and longer durations of illness tending to result in lower height measures than vice versa, although IGF-I levels in anorexic subjects may not necessarily be low enough to affect height measures.[93] In some cases, especially where onset is pre-pubertal, physical consequences such as stunted growth and pubertal delay are usually fully reversible.[98]

- Reduction of Peak Bone Mass – bone accretion is the highest during adolescence, and if onset of anorexia nervosa occurs during this time and stalls puberty, bone mass may remain low.[92]

- Hepatic steatosis – fatty infiltration of the liver is an indicator of malnutrition in children.[92]

- Heart disease and arrythmias

- Neurological disorders- seizures, tremors

- Acute gastric dilation, infarction and perforation,[99]

- Death (Anorexia nervosa has the highest rate of mortality of any psychological disorder):[100] [5-9 percent][101]

Causes

Studies have hypothesized the continuance of disordered eating patterns may be epiphenomena of starvation. The results of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment showed normal controls exhibit many of the behavioral patterns of anorexia nervosa (AN) when subjected to starvation. This may be due to the numerous changes in the neuroendocrine system, which results in a self-perpetuating cycle.[102][103][104][105] Studies have suggested the initial weight loss such as dieting may be the triggering factor in developing AN in some cases, possibly because of an already inherent predisposition toward AN. One study reported cases of AN resulting from unintended weight loss that resulted from varied causes, such as a parasitic infection, medication side effects, and surgery. The weight loss itself was the triggering factor.[106][107] Even though anorexia does not affect males as often in comparison to females, studies have shown that males with a female twin have a higher chance of getting anorexia. Therefore anorexia may be linked to intrauterine exposure to female hormones.[108]

Biological

- Obstetric complications: various prenatal and perinatal complications may factor into the development of anorexia nervosa, such as maternal anemia, diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, placental infarction, and neonatal cardiac abnormalities. Neonatal complications may also have an influence on harm avoidance, one of the personality traits associated with the development of AN.[109][110]

- Genetics: anorexia nervosa is believed to be highly heritable, with estimated inheritance rates ranging from 56% to 84%.[111][112][113] Twin studies have shown a heritability rate of 56%.[114][115] Association studies have been performed, studying 128 different polymorphisms related to 43 genes including genes involved in regulation of eating behavior, motivation and reward mechanics, personality traits and emotion. Consistent associations have been identified for polymorphisms associated with agouti-related peptide, brain derived neurotrophic factor, catechol-o-methyl transferase, SK3 and opioid receptor delta-1.[116] In one study, variations in the norepinephrine transporter gene promoter were associated with restrictive anorexia nervosa, but not binge-purge anorexia.[117]

- epigenetics: Epigenetic mechanisms: are means by which genetic mutations are caused by environmental effects that alter gene expression via methods such as DNA methylation, these are independent of and do not alter the underlying DNA sequence. They are heritable, as was shown in the Överkalix study, but also may occur throughout the lifespan, and are potentially reversible. Dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission and Atrial natriuretic peptide homeostasis resulting from epigenetic mechanisms has been implicated in various eating disorders.[118] "We conclude that epigenetic mechanisms may contribute to the known alterations of ANP homeostasis in women with eating disorders."[118][119]

Dysregulation of the dopamine and serotonin pathways has been implicated in the etiology, pathogenesis and pathophysiology of anorexia nervosa.[120][121][122][123]

- epigenetics: Epigenetic mechanisms: are means by which genetic mutations are caused by environmental effects that alter gene expression via methods such as DNA methylation, these are independent of and do not alter the underlying DNA sequence. They are heritable, as was shown in the Överkalix study, but also may occur throughout the lifespan, and are potentially reversible. Dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission and Atrial natriuretic peptide homeostasis resulting from epigenetic mechanisms has been implicated in various eating disorders.[118] "We conclude that epigenetic mechanisms may contribute to the known alterations of ANP homeostasis in women with eating disorders."[118][119]

- Addiction to the chemicals released in the brain during starving and physical activity;[124] people affected with anorexia often report getting some sort of high from not eating. The effect of food restriction and intense activity causes symptoms similar to anorexia in female rats,[124] though it is not explained why this addiction affects only females.

- Serotonin dysregulation; brain imaging studies implicate alterations of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors and the 5-HT transporter. Alterations of these circuits may affect mood and impulse control as well as the motivating and hedonic aspects of feeding behavior.[125] Starvation has been hypothesized to be a response to these effects, as it is known to lower tryptophan and steroid hormone metabolism, which might reduce serotonin levels at these critical sites and ward off anxiety.[125] Other studies of the 5HT2A serotonin receptor (linked to regulation of feeding, mood, and anxiety), suggest that serotonin activity is decreased at these sites. There is evidence that both personality characteristics associated with AN and disturbances to the serotonin system are still apparent after patients have recovered from anorexia.[126] Another study found AN to be significantly associated with the S allele and S carrier (SS + LS) genotype.[127]

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that regulates neuronal development and neuroplasticity, it also plays a role in learning, memory and in the hypothalamic pathway that controls eating behavior and energy homeostasis. BDNF amplifies neurotransmitter responses and promotes synaptic communication in the enteric nervous system. Low levels of BDNF are found in patients with AN and some comorbid disorders such as major depression.[128][129] Exercise increases levels of BDNF[130]

- Leptin and ghrelin; leptin is a hormone produced primarily by the fat cells in white adipose tissue of the body it has an inhibitory (anorexigenic) effect on appetite, by inducing a feeling of satiety. Ghrelin is an appetite inducing (orexigenic) hormone produced in the stomach and the upper portion of the small intestine. Circulating levels of both hormones are an important factor in weight control. While often associated with obesity both have been implicated in the pathophysiology of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.[131] A 2013 study revealed that anorectic subjects may have reduced ghrelin bioactivity due to altered carrier-antibody affinity, leading to less efficient transport of ghrelin to the brain and thus reduced hunger sensation.[132]

- Orexin; orexin is a neurotransmitter that regulates appetite and is responsible for increasing the craving for food.[133]

- Cerebral blood flow (CBF); neuroimaging studies have shown reduced CBF in the temporal lobes of anorectic patients, which may be a predisposing factor in the onset of AN.[134]

- Autoimmune system; Autoantibodies against neuropeptides such as melanocortin have been shown to affect personality traits associated with eating disorders such as those that influence appetite and stress responses.[135]

- Infections: Some people are hypothesized to have developed anorexia abruptly as a reaction to a streptococcus or mycoplasma infection. PANS is an acronym for Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, a hypothesis describing children who have abrupt, dramatic onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or anorexia nervosa coincident with the presence of two or more neuropsychiatric symptoms.[136]

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Zinc deficiency may play a role in anorexia. It is not thought responsible for causation of the initial illness but there is evidence that it may be an accelerating factor that deepens the pathology of the anorexia. A 1994 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that zinc (14 mg per day) doubled the rate of body mass increase compared to patients receiving the placebo.[137]

Sociological

Sociocultural studies have highlighted the role of cultural factors, such as the promotion of thinness as the ideal female form in Western industrialized nations. There is a possible connection between anorexia nervosa and culture; culture may be a cause, a trigger, or merely a kind of social address or envelope which determines in which segments of society or in which cultures anorexia nervosa will appear. The thesis of this connection is that culture acts as a cause by providing a blueprint for anorexia nervosa. A moderate thesis is that specific cultural factors trigger the illness which is determined by many factors including family interactions, individual psychology, or biological predisposition. Culture change can trigger the emergence of anorexia in adolescent girls from immigrant families living in highly industrialized Western Societies.[138] According to a study published in 1980, people in professions where there is a particular social pressure to be thin (such as models and dancers) were much more likely to develop anorexia during the course of their career,[139] and further research has suggested that those with anorexia have much higher contact with cultural sources that promote weight-loss.[140]

Anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in a person's pubertal years, especially for girls.[141] Female students are 10 times more likely to suffer from anorexia nervosa than male students. According to a survey of 1799 Japanese female high school students, "85% who were a normal weight wanted to be thinner and 45% who were 10–20% underweight wanted to be thinner."[142] Teenage girls concerned about their weight and who believe that slimness is more attractive among peers trend to weight-control behaviors. Teen girls learn from each other to consume low-caloric, low-fat foods and diet pills. This results in lack of nutrition and a greater chance of developing anorexia nervosa.[143]

It has also been noted that anorexia nervosa is more likely to occur in populations in which obesity is more prevalent. It has been suggested that anorexia nervosa results from a sexually selected evolutionary drive to appear youthful in populations in which size becomes the primary indicator of age.[144]

There is also evidence to suggest that patients who have anorexia nervosa can be characterised by alexithymia[145] and also a deficit in certain emotional functions. A research study showed that this was the case in both adult and adolescent anorexia nervosa patients.[146]

Early theories of the cause of anorexia linked it to sexual abuse or dysfunctional families. Some studies reported a high rate of reported child sexual abuse experiences in clinical groups of people who have been diagnosed with anorexia. One found that women with a history of eating disorders were twice as likely to have reported childhood sexual abuse compared to women with no history of eating disorders.[147] The joint effect of both physical and sexual abuse resulted in a nearly 4-fold risk of eating disorders that met DSM-IV criteria.[147] The conclusion was that links between childhood abuse and sexual abuse are complex, such as by influencing psychologic processes that increase a woman's susceptibility to the development of an eating disorder, or perhaps by producing changes in psychobiologic process and neurotransmitting function, associated with eating behaviour.[147]

In contrast to the above, a metastudy of published research examining causes of anorexia found no conclusive link between abuse, parenting and eating disorders.[148] The American Psychiatric Association writes: "No evidence exists to prove that families cause eating disorders."[149]

Efforts have been made to dispel some of the myths around anorexia nervosa and eating disorders, such as the misconception that families, in particular mothers, are responsible for their daughter developing an eating disorder.[150]

Media effects

There is no evidence[disputed – discuss] that the media is a cause of eating disorders, and advances in neuroscience point to a more complex combination of genetic and environmental influences.[151]

Mass media interventions may offer a distorted vision of the world, and it may be difficult for children and adolescents to distinguish whether what they see is real or not, so that they are more vulnerable to the messages transmitted. Field, Cheung, et al.'s survey of 548 preadolescent and adolescent girls found that 69% acknowledged that images in magazines had influenced their conception of the ideal body, while 47% reported that they wanted to lose weight after seeing such images.[152] There was also the survey by Utter et al. who studied 4,746 adolescent boys and girls demonstrating the tendency of magazine articles and advertisements to activate weight concerns and weight management behaviour. He discovered that girls who frequently read fashion and glamour magazines and girls who frequently read articles about diets and issues related to weight loss were seven times more likely to practice a range of unhealthy weight control behaviours and six times more likely to engage in extremely unhealthy weight control behaviours (e.g., taking diet pills, vomiting, using laxatives, and using diuretics). There was not stated though wether this behavior was a possible cause of anorexia nervosa or a result of the disease.[152] Websites that stress the message of thinness as the ideal have surfaced on the Internet and have managed to embed themselves as an increasing source of influence. The possibility that pro-anorexia websites may reinforce restrictive eating and exercise behaviours is an area of concern. Pro-anorexia websites contain images and writing that support the pursuit of an ideal thin body image. Research has shown that these websites stress thinness as the ideal choice for women and in some websites ideal images of muscularity and thinness for men[153] It has also been shown that women who had viewed these websites at least once had a decrease in self-esteem and reports also show an increased likelihood of future engagement in many negative behaviours related to food, exercise, and weight.[153] Evidence of the value of thinness in majority U.S culture is found in Hollywood's elite and the media promotion of waif models in fashion and celebrity circles (e.g. Nicole Richie, Mary Kate Olsen, Kate Moss, and Lady Gaga[154]).

Relationship to autism

Since Gillberg's (1983 & 1985)[156][157] and others' initial suggestion of relationship between anorexia nervosa and autism,[158][159] a large-scale longitudinal study into teenage-onset anorexia nervosa conducted in Sweden confirmed that 23% of people with a long-standing eating disorder are on the autism spectrum.[160][161][162][163][164][165][166] Those on the autism spectrum tend to have a worse outcome,[167] but may benefit from the combined use of behavioural and pharmacological therapies tailored to ameliorate autism rather than anorexia nervosa per se.[168][169] Other studies, most notably research conducted at the Maudsley Hospital, furthermore suggest that autistic traits are common in people with anorexia nervosa; shared traits include, e.g., poor executive function, autism quotient score, central coherence, theory of mind, cognitive-behavioural flexibility, emotion regulation and understanding facial expressions.[170][171][172][173][174][145]

Zucker et al. (2007) proposed that conditions on the autism spectrum make up the cognitive endophenotype underlying anorexia nervosa and appealed for increased interdisciplinary collaboration (see figure to right).[155] A pilot study into the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy, which based its treatment protocol on the hypothesised relationship between anorexia nervosa and an underlying autistic like condition, reduced perfectionism and rigidity in 17 out of 19 participants.[175]

Some autistic traits are more prominent during the acute phase of AN.[176]

Differential diagnoses

A variety of medical and psychological conditions have been misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa; in some cases the correct diagnosis was not made for more than ten years. In a reported case of achalasia misdiagnosed as AN, the patient spent two months confined to a psychiatric hospital.[177]

Other psychological issues may factor into anorexia nervosa; some fulfill the criteria for a separate Axis I diagnosis or a personality disorder which is coded Axis II and thus are considered comorbid to the diagnosed eating disorder. Axis II disorders are subtyped into 3 "clusters", A, B and C. The causality between personality disorders and eating disorders has yet to be fully established.[178] Some people have a previous disorder which may increase their vulnerability to developing an eating disorder.[179][180][181] Some develop them afterwards.[182] The presence of Axis I and/or Axis II psychiatric comorbidity has been shown to affect the severity and type of anorexia nervosa symptoms in both adolescents and adults.[183][184] In particular, substance abuse and borderline personality appear more frequent among anorexics who binge or purge.[185][186] And obsessive-compulsive personality disorder—according to some studies, the most common personality disorder among anorexics—and particular traits of this diagnosis such as perfectionism are linked with more severe symptomatology and worse prognosis.[187][188]

- Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is listed as a somatoform disorder that affects up to 2% of the population. BDD is characterized by excessive rumination over an actual or perceived physical flaw. BDD has been diagnosed equally among men and women. While BDD has been misdiagnosed as anorexia nervosa, it also occurs comorbidly in 25% to 39% of AN cases.[200]

BDD is a chronic and debilitating condition which may lead to social isolation, major depression, suicidal ideation and attempts. Neuroimaging studies to measure response to facial recognition have shown activity predominately in the left hemisphere in the left lateral prefrontal cortex, lateral temporal lobe and left parietal lobe showing hemispheric imbalance in information processing. There is a reported case of the development of BDD in a 21-year-old male following an inflammatory brain process. Neuroimaging showed the presence of new atrophy in the frontotemporal region.[201][202][203][203][204]

The distinction between the diagnoses of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) is often difficult to make as there is considerable overlap between patients diagnosed with these conditions. Seemingly minor changes in a patient's overall behavior or attitude can change a diagnosis from "anorexia: binge-eating type" to bulimia nervosa. A main factor differentiating binge-purge anorexia from bulimia is the gap in physical weight. Someone with bulimia nervosa is ordinarily at a healthy weight, or slightly overweight. Someone with binge-purge anorexia is commonly underweight.[205] It is not unusual for a person with an eating disorder to "move through" various diagnoses as their behavior and beliefs change over time.[155]

Treatment

There is no conclusive evidence that any particular treatment for anorexia nervosa works better than others; however, there is enough evidence to suggest that early intervention and treatment are more effective.[206] Treatment for anorexia nervosa tries to address three main areas.

- Restoring the person to a healthy weight;

- Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness;

- Reducing or eliminating behaviours or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.[207]

Although restoring the person's weight is the primary task at hand, optimal treatment also includes and monitors behavioral change in the individual as well.[45] Not all anorexia nervosa patients recover completely; About 20% develop anorexia nervosa as a chronic disorder.[208] If anorexia nervosa is not treated, serious complications such as heart conditions and kidney failure can arise and eventually lead to death. "As many as 6 percent of people with the disorder die from causes related to it."[209]

Dietary

Diet is the most essential factor to work on in patients with anorexia nervosa, and must be tailored to each patient's needs. Initial meal plans may be low in calories, about 1200, in order to build comfort in eating, and then food amount can gradually be increased. Food variety is important when establishing meal plans as well as foods that are higher in energy density. Other more specific dietary treatments are listed below.[210]

- Zinc: Zinc supplementation has been shown in various studies to be beneficial in the treatment of AN even in patients not suffering from zinc deficiency, by helping to increase weight gain. Patients with anorexia nervosa have a high likelihood of being zinc deficient, and this probability increases if they are vegetarians. Vegetarianism is adopted by many patients with eating disorders because it is widely acclaimed as healthy and easy to manage calorie intake.[211] Sufficient Zinc must be available during recovery, and normal zinc levels were seen in the Notre Dame study to increase weight gain at a faster rate. Zinc supplementation can also help reduce reproductive issues for patients with anorexia nervosa. Leptin levels, which regulate hunger and metabolism, decrease from zinc deficiency and even more with AN sufferers due to the reduction in size of adipose tissue. Reproductive tissues have been discovered to contain leptin receptors, thus a decrease in leptin concentration would lead to a lower rate of fertility. Despite the connection to weight gain and reproduction, zinc supplementation seems to be largely under-appreciated and many do not consider zinc deficiency as an important factor in regard to anorexia nervosa.[212]

- Calories: Patients must be fed adequate calories at a measured pace for improvement of their condition to occur. The best level for calorie intake is to start by providing 1200 to 1500 calories daily and increasing this amount by 500 each day. This process should continue until the level of 4000 calories (for male patients) or 3500 calories (for female patients) is achieved. This system should also decrease effects such as apathy, lethargy, and food-related obsessions.[213]

- Essential fatty acids: The omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) have been shown to benefit various neuropsychiatric disorders. There was reported rapid improvement in a case of severe AN treated with ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid (E-EPA) and micronutrients.[214] DHA and EPA supplementation has been shown to be a benefit in many of the comorbid disorders of AN including attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, major depressive disorder (MDD),[215] bipolar disorder, and borderline personality disorder. Accelerated cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) correlate with lowered tissue levels of DHA/EPA, and supplementation has improved cognitive function.[216][217]

- Nutritional counseling.[218][219]

- Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT), also referred to as Nutrition Therapy, is the development and provision of a nutritional treatment or therapy based on a detailed assessment of a person's medical history, psychosocial history, physical examination, and dietary history.[220][221][222]

Medication

- Olanzapine: There have been some claims that olanzapine is effective in treating certain aspects of AN including helping raise the body mass index and reducing obsessionality, including obsessional thoughts about food.[223][224] Olanzapine does not increase the rate of body mass index growth in patients with anorexia.[225]

Therapy

- Family-based treatment

Family-based treatment (FBT) has been shown in randomized controlled trials to be more successful than individual therapy in most treatment trials.[45] Several components of family therapy for patients with AN are:

- the family is seen as a resource for the adolescent[226]

- anorexia nervosa is reframed in benign, non blaming terms[226]

- directives are provided to parents so that they may take charge of their child or adolescent's eating routine[226]

- a structured behavioral weight gain program is implemented[226]

- after weight gain, control over eating is gradually returned to the child or adolescent[226]

- as the child or adolescent begins to eat and gain weight, the therapeutic focus broadens to include family interaction problems, growth and autonomy issues and parent–child conflicts[226]

Various forms of family-based treatment have been proven to work in the treatment of adolescent AN including "conjoint family therapy" (CFT), in which the parents and child are seen together by the same therapist, "separated family therapy" (SFT) in which the parents and child attend therapy separately with different therapists. "Eisler's cohort show that, irrespective of the type of FBT, 75% of patients have a good outcome, 15% an intermediate outcome ...".[227][228] Proponents of Family therapy for adolescents with AN assert that it is important to include parents in the adolescent's treatment.[229]

A four- to five-year follow up study of the Maudsley family therapy, an evidence-based manualized model, showed full recovery at rates up to 90%.[230] Although this model is recommended by the NIMH,[231] critics claim that it has the potential to create power struggles in an intimate relationship and may disrupt equal partnerships.[232]

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence based approach which in studies to date has shown to be useful in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa.[233][234][235] Components of using CBT with adults and adolescents with anorexia nervosa have been outlined by several professionals as:

- the therapist focuses on using cognitive restructuring to modify distorted beliefs and attitudes about the meaning of weight, shape and appearance[226]

- specific behavioral techniques addressing the normalization of eating patterns and weight restorations, examples of this include the use of a food diary, meal plans, and incremental weight gain[226]

- cognitive techniques such as restructuring, problem solving, and identification and expression of affect[226]

- When using CBT with adolescents and children with AN, several professionals have expressed concerns about the minimum age and level of cognition necessary for implementing cognitive behavioral techniques.[226] Modified versions and elements of CBT can be implemented with children and adolescents with AN. Such modifications may include the use of behavioral experiments to disconfirm distorted beliefs and absolutistic thinking in children and adolescents.[226]

- Acceptance and commitment therapy

Acceptance and commitment therapy is a type of CBT, which has shown promise in the treatment of AN" participants experienced clinically significant improvement on at least some measures; no participants worsened or lost weight even at 1-year follow-up."[236]

- Cognitive remediation therapy

Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) is a cognitive rehabilitation therapy developed at King's College in London designed to improve neurocognitive abilities such as attention, working memory, cognitive flexibility and planning, and executive functioning which leads to improved social functioning. Neuropsychological studies have shown that patients with AN have difficulties in cognitive flexibility. In studies conducted at Kings College[237] and in Poland with adolescents CRT was proven to be beneficial in treating anorexia nervosa,[237] in the United States clinical trials are still being conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health[238] on adolescents age 10–17 and Stanford University in subjects over 16 as a conjunctive therapy with Cognitive behavioral therapy.[239]

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis of anorexia nervosa is more on the favorable side. The National Comorbidity Replication Survey was conducted among more than 9,282 participants throughout the United States; ` found that the average duration of anorexia nervosa is 1.7 years. "Contrary to what people may believe, anorexia is not necessarily a chronic illness; in many cases, it runs its course and people get better ..."[240] However, 5–20% of people diagnosed with anorexia nervosa die from it, and the cause of death is mostly because of the direct health effects of the eating disorder on the body.[241]

In cases of adolescent anorexia nervosa where family-based treatment is used, 75% of patients have a good outcome and an additional 15% show an intermediate yet more positive outcome.[227] In a five-year post treatment follow-up of Maudsley Family Therapy the full recovery rate was between 75% and 90%.[242]

Some remedies, however, are proven to not have any value in resolving anorexia. "Incarceration in hospital" prohibits patients from many basic rights, such as using the bathroom independently. Therefore, it has been seen as catalytic in increasing weight and pushing patients away from the path to recovery.[243]

According to a 1997 study, even in severe cases of AN, despite a noted 30% relapse rate after hospitalization, and a lengthy time to recovery ranging from 57 to 79 months, the full recovery rate was still 76%. There were minimal cases of relapse even at the long term follow-up conducted between 10–15 years.[244] The long-term prognosis of anorexia nervosa is changeable: a fifth of patients stay severely ill, another fifth of patients recover fully and three fifths of patients have a fluctuating and chronic course.[245]

Although overall the prognosis may seem favorable, this is not the case for all patients of anorexia nervosa. Among psychiatric disorders, anorexia nervosa has one of the highest mortality rates because of side effects of the disorder, such as cardiac complications or suicide. In intermediate to long-term studies with juveniles, death rates, on average, have ranged anywhere from 1.8 to 14.1%.[246] Recovery can be lifelong for some; energy intake and eating habits may never return to normal.[210] Many studies have attempted to study relapse and recovery through longitudinal studies but this is difficult, time consuming, and costly. Recovery is also viewed on a spectrum rather than black and white. According to the Morgan-Russell criteria patients can have a good, intermediate, or poor outcome. Even when a patient is classified as having a "good" outcome, weight only has to be within 15% of average and normal menstruation must be present in females. The good outcome also excludes psychological health. Recovery for patients with anorexia nervosa is undeniably positive, but recovery does not mean normal.[246]

Relapse

According to the Eckert study, relapse is greatest in the first year after normal body weight is obtained. This includes right after release from inpatient institutions. Relapse includes a return to food restriction as well as a shift to binge eating habits.

As stated above, higher energy density in dietary plans is important. Patients with lower dietary energy density in their meals, prior to being discharged, had worse outcomes within the year, therefore a higher likelihood of relapse. This is speculated to be due to fat and fluid consumption. Patients whose dietary plans included fats and foods containing fats were forced to eat a more realistic and "normal" plan than those with lower energy density. Therefore, when released from inpatient treatment, the patients with higher dietary energy density plans had adopted healthier and more balanced eating habits. A greater food variety in inpatient dietary plans may help lower rates of relapse as well.[247] Relapse, binging or starving after initial weight gain, occurs in 40–70% of anorexia patients.[248] Prevention of relapse can be helped by cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacological therapies.[248] Link of OCD with anorexia shows treatments for OCD such as serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI) helps in preventing relapse.[248]

Several clinically significant variables that could predict relapse among AN patients were identified in a study conducted by a team at the University of Toronto. First, patients with binge-purge type AN were twice as likely to have a relapse as those with restricting subtype AN. The second predictor of relapse was the level of motivation to recover. When patients' motivation to recover fell during the first 4 weeks of inpatient treatment, the risk of relapse rose. The third predictor identified in the study was higher pre-treatment severity of checking behaviors, as reported on the Padua Inventory (PI) Checking Behavior scale, a measure of obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms.[249]

Epidemiology

Anorexia has an average prevalence of 0.3–1% in women and 0.1% in men for the diagnosis in developed countries.[250] The condition largely affects young adolescent women, with those between 15 and 19 years old making up 40% of all cases. Approximately 75% of people with anorexia are female.[251] Anorexia nervosa is more prevalent in the upper social classes and it is thought to be rare in less-developed countries.[245] Anorexia is more prevalent in females and males born after 1945.[252] The lifetime incidence of atypical anorexia nervosa, a form of ED-NOS in which not all of the diagnostic criteria for AN are met, is much higher, at 5–12%.[253]

The question of whether the incidence of AN is on the rise has been under debate. Most studies show that since at least 1970 the incidence of AN in adult women is fairly constant, while there is some indication that the incidence may have been increasing for girls aged between 14 and 20.[254] It is difficult to compare incidence rates at different times and possibly different locations due to changes in methods of diagnosing, reporting and changes in the population numbers, as evidenced on data from after 1970.[255][256][257]

History

The term anorexia nervosa was coined in 1873 by Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria's personal physicians.[258] The term is of Greek origin: an- (ἀν-, prefix denoting negation) and orexis (ὄρεξις, "appetite"), thus meaning a lack of desire to eat.[259]

The history of anorexia nervosa begins with descriptions of religious fasting dating from the Hellenistic era[260] and continuing into the medieval period. A number of well known historical figures, including Catherine of Siena and Mary, Queen of Scots are believed to have suffered from the condition.[261][262]

The medieval practice of self-starvation by women, including some young women, in the name of religious piety and purity also concerns anorexia nervosa; it is sometimes referred to as anorexia mirabilis. By the thirteenth century, it was increasingly common for women to participate in religious life and to even be named as saints by the Catholic Church. Many women who ultimately became saints engaged in self-starvation, including Saint Hedwig of Andechs in the thirteenth century and Catherine of Siena in the fourteenth century. By the time of Catherine of Siena, however, the Church became concerned about extreme fasting as an indicator of spirituality and as a criterion for sainthood. Catherine of Siena was told by Church authorities to pray that she would be able to eat again, but was unable to give up fasting.[261]

The earliest medical descriptions of anorexic illnesses are generally credited to English physician Richard Morton in 1689.[260] Case descriptions fitting anorexic illnesses continued throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They include the cases of an 18-year-old girl treated by Richard Morton in 1689 who refused to eat and died 3 months later.[263] Noah Webster writes of an instructor at Yale College in the 1770s who refused to eat because he believed food was "dulling his mind."[264]

However, it was not until the late 19th century that anorexia nervosa was widely accepted by the medical profession as a recognised condition. In 1873, Sir William Gull, one of Queen Victoria's personal physicians, published a seminal paper which coined the term anorexia nervosa and provided a number of detailed case descriptions and treatments. However, Gull was unable to provide an explanation for the condition.[263] In the same year, French physician Ernest-Charles Lasègue similarly published details of a number of cases in a paper entitled De l'Anorexie Histerique.

Awareness of the condition was largely limited to the medical profession until the latter part of the 20th century, when German-American psychoanalyst Hilde Bruch published The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa in 1978. This book created a wider interest in anorexia nervosa among lay readers. Bruch postulated that anorexia nervosa is a "desperate struggle for a self-respecting identity". Despite major advances in neuroscience,[151] Bruch's theories tend to dominate popular thinking. A further important event was the death of the popular singer and drummer Karen Carpenter in 1983, which prompted widespread ongoing media coverage of eating disorders. Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness[265] and continues to be in the public eye. "Pro-ana" websites range from those claiming to be a safe-space for anorexics to discuss their problems, to those supporting anorexia as a lifestyle choice and offering "thinspiration," or photos and videos of thin or emaciated women. A survey by Internet security firm Optenet found a 470% increase in pro-ana and pro-mia (as in bulimia) sites from 2006 to 2007.[266] Many celebrities have come forward discussing their struggles with anorexia, increasing awareness of the disease. Celebrities who have come forward publicly to discuss their experiences with anorexia include singer Fiona Apple, who purposely lost weight to discourage unwanted sexual advances after being raped at age 12,[267] Portia de Rossi,[268] Calista Flockhart,[269] Tracey Gold,[270] whose difficult recovery was well publicized by the media after her weight dropped to 80 pounds (36 kg) on her 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m) frame and she was hospitalized,[271] Mary-Kate Olsen,[272] Alanis Morissette,[273] and French model Isabelle Caro, who died due to complications related to anorexia.

See also

- List of people with anorexia nervosa

- Anti-fat bias

- Binge eating disorder

- Bulimia nervosa

- Caloric restriction

- Cigarette smoking for weight loss

- Depression (differential diagnoses)

- Eating disorders and development

- Eating Recovery

- Hungry: A Mother and Daughter Fight Anorexia (book)

- Life-Size (novel)

- Marya Hornbacher

- Muscle dysmorphia

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders

- Orthorexia nervosa

- Pro-ana

- Weight phobia

- Sandra Lahire

References

- ^ Hockenbury, Don and Hockenbury, Sandra (2008) Psychology, p. 593. Worth Publishers, New York. ISBN 978-1-4292-0143-8.

- ^ a b Carlson N., Heth C., Miller Harold, Donahoe John, Buskist William, Martin G., Schmaltz Rodney (2007). Psychology: the science of behaviour-4th Canadian ed. Toronto, ON: Pearson Education Canada. pp. 414–415. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rosen JC, Reiter J, Orosan P (1995). "Assessment of body image in eating disorders with the body dysmorphic disorder examination". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 33 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0030-M. PMID 7872941.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cooper MJ (2005). "Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: progress, development and future directions". Clinical Psychology Review. 25 (4): 511–31. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.003. PMID 15914267.

- ^ Brooks S, Prince A, Stahl D, Campbell IC, Treasure J (2010). "A systematic review & meta-analysis of cognitive bias to food stimuli in people with disordered eating behaviour". Clinical Psychology. 31 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.006. PMID 21130935.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Neil Frude (1998). Understanding abnormal psychology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-16195-0. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b Attia E (2010). "Anorexia Nervosa: Current Status and Future Directions". Annual Review of Medicine. 61 (1): 425–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.050208.200745. PMID 19719398.

- ^ "Research on Males and Eating Disorders". National Eating Disorders Association. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ "What is Anorexia Nervosa?". Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. Archived from the original on 2010-04-21.

- ^ Burd, C., Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Engel, S. G., Wonderlich, S. A., Lystad, C., & ... Crow, S. (2009). An assessment of daily food intake in participants with anorexia nervosa in the natural environment. International Journal Of Eating Disorders, 42(4), 371-374.

- ^ Schleimer, Kari (1981). "Anorexia Nervosa". Nutrition Reviews. 39 (2): 99. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1981.tb06739.x.

- ^ Westen D, Harnden-Fischer J (2001). "Personality profiles in eating disorders: rethinking the distinction between axis I and axis II". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (4): 547–62. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.547. PMID 11282688.

- ^ http://www.eatingdisorders.org.au/eating-disorders/classifying-eating-disorders/dsm-5#anorexia

- ^ a b Yale, Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, (2014). Abnormal psychology (Sixth edition. ed.). McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages. p. 339. ISBN 0078035384.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online2003/fr-icd.htm?gf50.htm+

- ^ "CBC". MedlinePlus : U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Urinalysis at Medline. Nlm.nih.gov (2012-01-26). Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ Kawabata M, Kubo N, Arashima Y, Yoshida M, Kawano K (1991). "[Serodiagnosis of Lyme disease by ELISA using Borrelia burgdorferi flagellum antigen]". Rinsho Byori (in Japanese). 39 (8): 891–4. PMID 1920889.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ [1]

- ^ Chem-20 at Medline. Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ Lee H, Oh JY, Sung YA, Chung H, Cho WY (2009). "The prevalence and risk factors for glucose intolerance in young Korean women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Endocrine. 36 (2): 326–32. doi:10.1007/s12020-009-9226-7. PMID 19688613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Takeda N, Yasuda K, Horiya T, Yamada H, Imai T, Kitada M, Miura K (1986). "[Clinical investigation on the mechanism of glucose intolerance in Cushing's syndrome]". Nippon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi (in Japanese). 62 (5): 631–48. PMID 3525245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rolny P, Lukes PJ, Gamklou R, Jagenburg R, Nilson A (1978). "A comparative evaluation of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography and secretin-CCK test in the diagnosis of pancreatic disease". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (7): 777–81. doi:10.3109/00365527809182190. PMID 725498.