War guilt question: Difference between revisions

→top: Translation WIP banners. |

→Background: Add intro section about WW1 to provide context for the development of the WGQ. Content in this edit copied and adapted from World War I rev. 995817589, Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) rev. 994319334, and World War I reparations rev 991749335; see those articles' histories for attribution. |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

A century later, debate continues into the 21st century. The main outlines of the debate include: how much diplomatic and political room to maneuver was available; the inevitable consequences of pre-war armament policies; the role of domestic policy and social and economic tensions in the foreign relations of the states involved; the role of public opinion and their experience of war in the face of organized propaganda;{{sfn|Thoss|1994|p=1012-1039}} the role of economic interests and top military commanders in torpedoing deescalation and peace negotiations; the "Special path" ({{lang|de|Sonderweg}}) theory; and the long-term trends which tend to contextualize the First World War as a condition or preparation for the Second, such as [[Raymond Aron]] who views the two world wars as the new [[Thirty Years' War]], a theory reprised by Enzo Traverso in his work.{{sfn|Traverso|2017|p=}}{{page needed|reason=Needs to be an electronic page indicator (e.g, 'PT25' in gbooks) because it's an eFile.|date=July 2020}} |

A century later, debate continues into the 21st century. The main outlines of the debate include: how much diplomatic and political room to maneuver was available; the inevitable consequences of pre-war armament policies; the role of domestic policy and social and economic tensions in the foreign relations of the states involved; the role of public opinion and their experience of war in the face of organized propaganda;{{sfn|Thoss|1994|p=1012-1039}} the role of economic interests and top military commanders in torpedoing deescalation and peace negotiations; the "Special path" ({{lang|de|Sonderweg}}) theory; and the long-term trends which tend to contextualize the First World War as a condition or preparation for the Second, such as [[Raymond Aron]] who views the two world wars as the new [[Thirty Years' War]], a theory reprised by Enzo Traverso in his work.{{sfn|Traverso|2017|p=}}{{page needed|reason=Needs to be an electronic page indicator (e.g, 'PT25' in gbooks) because it's an eFile.|date=July 2020}} |

||

== Background: World War I == |

|||

The question of German war guilt ({{lang-de|Kriegschuldfrage}}) took place in the context of the German defeat in [[World War I]], during and after the treaties that established the peace, and continuing on throughout the fifteen-year life of the [[Weimar Republic]] in Germany from 1919 to 1933, and beyond. |

|||

=== Outbreak of war === |

|||

{{Main|World War I}} |

|||

Hostilities in [[World War I]] took place mostly in Europe between 1914 and 11 November 1918, and involved mobilization of 70 million [[military personnel]] and resulted in over 20 million military and civilian deaths<ref name="EB-WWI">{{Cite web |title=World War I – Killed, wounded, and missing |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I |website=Encyclopedia Britannica }}</ref> (exclusive of fatalities from the [[1918 Spanish flu pandemic]], which accounted for millions more) making it one of the largest and deadliest wars in history.{{sfn|Keegan|1998|p=8}} By July 1914, the [[great powers]] of Europe were divided into two coalitions: the [[Triple Entente]], later called the "[[Allied Powers of World War I|Allied Powers]]", consisting of [[French Third Republic|France]], [[Russian Empire|Russia]], and [[British Empire|Britain]]; and the [[Triple Alliance (1882)|Triple Alliance]] of [[German Empire|Germany]], [[Austria-Hungary]], and [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]] (the "Central Powers"). After a series of events, ultimatums, and mobilizations, some of them due to [[Political and military alliances#Political and military alliances|interlocking alliances]], Germany [[German entry into World War I#July: crisis and war|declared war on Russia]] on 1 August. Within days the other powers followed suit, and before the end of the month the war extended to Japan (siding with Britain) and in November, to the Ottoman Empire (with Germany). |

|||

After four years of war on multiple fronts in Europe and around the world, an [[Hundred Days Offensive|Allied offensive]] began in August 1918, and the position of Germany and the Central Powers deteriorated, leading them to sue for peace. Initial offers were rejected, and Germany's position became more desperate. Awareness of impending military defeat sparked [[German Revolution of 1918–1919|revolution in Germany]], proclamation of a republic on 9 November 1918, the abdication of [[Kaiser Wilhelm II]], and German surrender, marking the end of [[Imperial Germany]] and the beginning of the [[Weimar Republic]]. The Central Powers collapsed, with the new Republic capitulating to the victorious Allies and ending hostilities by signing the [[Armistice of 11 November 1918]] in a railroad car. |

|||

=== Concluding peace === |

|||

{{Further|Treaty of Versailles|Article 231}} |

|||

Though hostilities ended on 11 November, a formal state of war continued for months, and various treaties were signed amongst the former belligerents. The [[Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920)|Paris Peace Conference]] set terms for the defeated Central Powers, created the [[League of Nations]], rewrote the map of Europe, and under the terms of [[Article 231]] of the [[Treaty of Versailles]], imposed financial penalties in which Germany had to pay [[World War I reparations|reparations]] of 132 billion [[gold marks]] (USD $33 billion) to the Allied Powers. In addition, Article 231 stated that "Germany accepts responsibility of Germany and her allies causing all the loss and damage..."{{sfn|Binkley|Mahr|1926|p=399–400}} but was mistranslated or interpreted in Germany as an admission by Germany of responsibility for causing the war. This, plus the heavy burden of reparations was taken as an injustice and national humiliation, and that Germany had signed "away her honor".{{sfn|Morrow|2005|p=290}} |

|||

== In the Weimar Republic == |

== In the Weimar Republic == |

||

| Line 351: | Line 368: | ||

* <!--{{sfn|Altmann|Scriba|2014}}-->{{cite web |lang=de |last1=Altmann |first1=Gerhard |last2=Scriba |first2=Arnulf |title=LeMO Kapitel - Weimarer Republik - Innenpolitik - Kriegsschuldreferat |trans-title=Weimar Republic Domestic policy - War Guilt Section |url=http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/weimar/innenpolitik/referat/index.html |date=14 September 2014 |website=Deutsches Historisches Museum |publisher= }} |

* <!--{{sfn|Altmann|Scriba|2014}}-->{{cite web |lang=de |last1=Altmann |first1=Gerhard |last2=Scriba |first2=Arnulf |title=LeMO Kapitel - Weimarer Republik - Innenpolitik - Kriegsschuldreferat |trans-title=Weimar Republic Domestic policy - War Guilt Section |url=http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/weimar/innenpolitik/referat/index.html |date=14 September 2014 |website=Deutsches Historisches Museum |publisher= }} |

||

<!--{{sfn|Binkley|Mahr|1926|p=}}--> |

|||

* {{Cite journal |last1=Binkley |first1=Robert C. |author1-link=Robert C. Binkley |last2=Mahr |first2=Dr. A. C. |date=June 1926 |title=A New Interpretation of the "Responsibility" Clause in the Versailles Treaty |journal=[[Current History]] |volume= 24 |issue=3 |pages=398–400}} |

|||

* <!--{{sfn|Fabian|1926|p=}}-->{{cite book |lang=de |author1=Walter Fabian |trans-title=The War Guilt Question. Basic and Factual Information on its Solution |title=Die Kriegsschuldfrage. Grunsätzliches und Tatsächliches zu ihrer Lösung |location=Leipzig |publisher=1. Auflage |year=1985 |orig-year=1926 |isbn=3-924444-08-0 |ref={{harvid|Fabian|1926}} }} |

* <!--{{sfn|Fabian|1926|p=}}-->{{cite book |lang=de |author1=Walter Fabian |trans-title=The War Guilt Question. Basic and Factual Information on its Solution |title=Die Kriegsschuldfrage. Grunsätzliches und Tatsächliches zu ihrer Lösung |location=Leipzig |publisher=1. Auflage |year=1985 |orig-year=1926 |isbn=3-924444-08-0 |ref={{harvid|Fabian|1926}} }} |

||

| Line 367: | Line 387: | ||

<!--{{sfn|Isaac|1933|p=}}--> |

<!--{{sfn|Isaac|1933|p=}}--> |

||

* {{cite book |last=Isaac |first=Jules|title=Un débat historique: le problème des origines de la guerre |trans-title=A Historic Debate: the Problem of the Origins of the War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QhvIAAAAMAAJ |year=1933 |publisher=Rieder |location=Paris |oclc=487772456}} |

* {{cite book |last=Isaac |first=Jules|title=Un débat historique: le problème des origines de la guerre |trans-title=A Historic Debate: the Problem of the Origins of the War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QhvIAAAAMAAJ |year=1933 |publisher=Rieder |location=Paris |oclc=487772456}} |

||

* <!--{{sfn|Keegan|1998|p=}}--> |

|||

{{cite book |last=Keegan |first=John |author-link=John Keegan |title=The First World War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oNtmAAAAMAAJ |publisher=Hutchinson |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-09-180178-6 |oclc=1167992766}} |

|||

<!-- {{sfn|Krüger|1985|p=}}--> |

<!-- {{sfn|Krüger|1985|p=}}--> |

||

| Line 376: | Line 399: | ||

<!--{{sfn|Mombauer|2013|p=}}--> |

<!--{{sfn|Mombauer|2013|p=}}--> |

||

* {{cite book |last=Mombauer |first=Annika |title=The Origins of the First World War: Controversies and Consensus |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VhFEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA51 |date=2 December 2013 |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, England |isbn=978-1-317-87584-0 |chapter=The German 'innocence campaign' |oclc=864746118}} |

* {{cite book |last=Mombauer |first=Annika |title=The Origins of the First World War: Controversies and Consensus |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VhFEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA51 |date=2 December 2013 |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, England |isbn=978-1-317-87584-0 |chapter=The German 'innocence campaign' |oclc=864746118}} |

||

<!--{{sfn|Morrow|2005|p=}}--> |

|||

* {{Cite book |first=John H. |last=Morrow |title=The Great War: An Imperial History |publisher=Routledge |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-415-20440-8}} |

|||

<!--{{sfn|Poidevin|1972|p=}}--> |

<!--{{sfn|Poidevin|1972|p=}}--> |

||

| Line 507: | Line 533: | ||

[[Category:Causes of World War I| ]] |

[[Category:Causes of World War I| ]] |

||

[[Category:Causes of wars|World War I]] |

[[Category:Causes of wars|World War I]] |

||

[[Category:Aftermath of World War I]] |

|||

[[Category:Weimar Republic]] |

[[Category:Weimar Republic]] |

||

[[Category:Historiography of World War I]] |

[[Category:Historiography of World War I]] |

||

[[Category:Causes of World War I]] |

[[Category:Causes of World War I]] |

||

[[Category:Politics of World War I]] |

[[Category:Politics of World War I]] |

||

[[Category:World War I propaganda]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 11:02, 23 December 2020

This article is in the process of being translated from French in the kriegsschuldfrage-language Wikipedia. In order to reduce edit conflicts, please consider not editing it while translation is in progress. |

This article is in the process of being translated from German in the kriegsschuldfrage-language Wikipedia. In order to reduce edit conflicts, please consider not editing it while translation is in progress. |

- Note: If you drop translated/copied content anywhere in this article, you must provide proper attribution in the edit summary, per Wikipedia's licensing requirements. Either of these two edit summaries satisfies the requirement:

Content in this edit is translated from the existing French Wikipedia article at [[:fr:FRENCH-ARTICLE-NAME]]; see its history for attribution.- French –

Content in this edit is [[WP:TFOLWP|translated]] from the existing French Wikipedia article at [[:fr:Kriegsschuldfrage]] rev [[:fr:Special:Permalink/177544216|177544216]]; see its history for attribution. - German –

Content in this edit is [[WP:TFOLWP|translated]] from the existing German Wikipedia article at [[:de:Kriegsschuldfrage]] rev [[:de:Special:Permalink/206426149|206426149]]; see its history for attribution. Content in this edit is copied from the existing Wikipedia article at [[ENGLISH-ARTICLE-NAME]]; see its history for attribution.

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

[[Category:Use American English from {{subst:July}} 2020]] [[Category:Use dmy dates from {{subst:July}} 2020]]

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

The war guilt question (Kriegsschuldfrage) is the public debate that took place in Germany for the most part during the Weimar Republic, to establish Germany's share of responsibility in the causes of the First World War. Structured in several phases, and largely determined by the impact of the Treaty of Versailles and the attitude of the victorious Allies, this debate also took place in other countries involved in the conflict, such as in France and Great Britain.

The war guilt debate motivated historians such as Hans Delbrück, Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Gerhard Hirschfeld, and Fritz Fischer, but also a much wider circle including intellectuals such as Kurt Tucholsky or Siegfried Jacobsohn, as well as the general public. The Kriegsschuldfrage pervaded the history of the Weimar Republic: founded shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, Weimar embodied this debate until its demise, which was subsequently taken up as a campaign argument by the National Socialists.

While the war guilt question made it possible to investigate the deep-rooted causes of the First World War, although not without provoking a great deal of controversy, it also made it possible to identify other aspects of the conflict, such as the role of the masses and the question of the Sonderweg. This debate, which obstructed German political progress for many years, also showed that politicians such as Gustav Stresemann were able to confront the war guilt question by advancing the general discussion without compromising German interests.

A century later, debate continues into the 21st century. The main outlines of the debate include: how much diplomatic and political room to maneuver was available; the inevitable consequences of pre-war armament policies; the role of domestic policy and social and economic tensions in the foreign relations of the states involved; the role of public opinion and their experience of war in the face of organized propaganda;[1] the role of economic interests and top military commanders in torpedoing deescalation and peace negotiations; the "Special path" (Sonderweg) theory; and the long-term trends which tend to contextualize the First World War as a condition or preparation for the Second, such as Raymond Aron who views the two world wars as the new Thirty Years' War, a theory reprised by Enzo Traverso in his work.[2][page needed]

Background: World War I

The question of German war guilt (German: Kriegschuldfrage) took place in the context of the German defeat in World War I, during and after the treaties that established the peace, and continuing on throughout the fifteen-year life of the Weimar Republic in Germany from 1919 to 1933, and beyond.

Outbreak of war

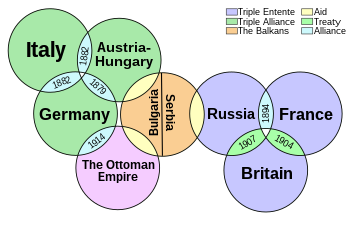

Hostilities in World War I took place mostly in Europe between 1914 and 11 November 1918, and involved mobilization of 70 million military personnel and resulted in over 20 million military and civilian deaths[3] (exclusive of fatalities from the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which accounted for millions more) making it one of the largest and deadliest wars in history.[4] By July 1914, the great powers of Europe were divided into two coalitions: the Triple Entente, later called the "Allied Powers", consisting of France, Russia, and Britain; and the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (the "Central Powers"). After a series of events, ultimatums, and mobilizations, some of them due to interlocking alliances, Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August. Within days the other powers followed suit, and before the end of the month the war extended to Japan (siding with Britain) and in November, to the Ottoman Empire (with Germany).

After four years of war on multiple fronts in Europe and around the world, an Allied offensive began in August 1918, and the position of Germany and the Central Powers deteriorated, leading them to sue for peace. Initial offers were rejected, and Germany's position became more desperate. Awareness of impending military defeat sparked revolution in Germany, proclamation of a republic on 9 November 1918, the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and German surrender, marking the end of Imperial Germany and the beginning of the Weimar Republic. The Central Powers collapsed, with the new Republic capitulating to the victorious Allies and ending hostilities by signing the Armistice of 11 November 1918 in a railroad car.

Concluding peace

Though hostilities ended on 11 November, a formal state of war continued for months, and various treaties were signed amongst the former belligerents. The Paris Peace Conference set terms for the defeated Central Powers, created the League of Nations, rewrote the map of Europe, and under the terms of Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, imposed financial penalties in which Germany had to pay reparations of 132 billion gold marks (USD $33 billion) to the Allied Powers. In addition, Article 231 stated that "Germany accepts responsibility of Germany and her allies causing all the loss and damage..."[5] but was mistranslated or interpreted in Germany as an admission by Germany of responsibility for causing the war. This, plus the heavy burden of reparations was taken as an injustice and national humiliation, and that Germany had signed "away her honor".[6]

In the Weimar Republic

Treaty of Versailles

Overview and Treaty clauses

The four great powers led by Woodrow Wilson for the Americans, Georges Clemenceau for the French, David Lloyd George for the British and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando for the Italians met to prepare the peace treaty. Rather than sticking to Wilson's 14 Points, the European vision quickly took hold. Decisions were made without Germany, which was excluded from the debates. France, which had served as the main battleground, wanted to ensure a peace of revenge through Clemenceau: "The time has come for a heavy settling of scores".[a][7] The Treaty of Versailles was above all a "treaty of fear": each former enemy tried to protect his own country. Moreover, the Allies still behaved like enemies when they presented the peace conditions to the German delegation, which finally was invited to attend on 7 May 1919. The deadline for ratification was in fifteen days; after that, military operations could resume.[citation needed]

Impact in Germany

Before the treaty was signed on June 28, 1919, the government of the Reich was already talking about an upheaval.[8] President Friedrich Ebert spoke on 6 February 1919 upon the opening of the Reichstag, of "revenge and plans for rape".[9] Germany was stunned by the terms of the treaty. The government claimed it was a ploy to dishonor the German people.[9] The impact of the treaty was first and foremost moral. The moral punishment was a heavier burden to bear than the material one. Treaty clauses that reduced territory, the economy, and sovereignty were seen as a means of making Germany morally grovel. The new Weimar Republic underscored the unprecedented injustice of the treaty[9], which was described as an act of violence and a Diktat. Article 231, the so-called "War Guilt Clause", put the responsibility for the war on Germany.

For Foreign Minister Brockdorff-Rantzau, recognition of Germany as having sole culpability was a lie.[10]. He resigned in June 1919 to avoid having to sign the treaty, which bore the seeds of its own rebuttal. Brockdorff-Rantzau had moreover said before the Allies at Versailles: "But also in the manner of waging war, Germany wasn't the only one to make mistakes, each nation made them. I do not wish to respond to accusations with accusations, but if we are asked to make amends, we must not forget the armistice."[11][b] The violence with which the treaty was imposed forced the Germans to refute it. By its nature, the treaty deprived the Weimar Republic of any historical confrontation with its own history. The thesis of responsibility derived its strength from the fact that for the first time, a country's responsibility had been officially established.

Reactions

Calls for an International tribunal

While representatives of the Indpendent Social Democratic and the Communist parties tended to emphasize the moral war guilt of the imperial leaders and associated it with social rather than legal consequences, the provisional government in Berlin in early 1919 called for a "neutral" international court to exclude the question of war guilt from the upcoming Paris peace negotiations.

With similar objectives, a number of national liberals, including Max von Baden, Paul Rohrbach, Max Weber, Friedrich Meinecke, Ernst Troeltsch, Lujo Brentano and Conrad Haussmann [de], founded a "Working Group for a Policy of Justice" (Heidelberg Association)[c] on 3 February 1919. It attempted to clarify the question of guilt scientifically, and wanted to have the degree of culpability and violations of international law examined by an arbitration court. It combined this with criticism of the policy of the Entente powers toward Germany and fought their alleged "war guilt lie"[d] even before the Treaty of Versailles was signed. A four-member delegation of the Association was to reject the Allied theories of war guilt on behalf of the Foreign Office and, to this end, handed over a "Memorandum on the Examination of the War Guilt Question" (also called the "Professorial Memorandum") in Versailles.[12][13]

After the Allies rejected the proposals and demanded instead the extradition of the "war-culpable individuals"[e], Otto Landsknecht (MSPD Bavaria) called for a national state tribunal on 12 March 1919, to try them.[citation needed] This was supported by only a few SPD representatives, including Philipp Scheidemann. As a result, ex-general Erich Ludendorff attacked him violently and accused the government representatives of treason in the sense of the stab in the back myth. After the conditions of Versailles became known, they demanded the deletion of the paragraph on the extradition of the "war-guilty"[e].

Propaganda response

At the beginning of World War I, all of the main combatants published bound versions of diplomatic correspondence, with greater or lesser accuracy, partly for domestic consumption and also partly to influence other actors about the responsibility for the war. The German White Book was the first of these to appear, and was published in 1914, with numerous other color books appearing shortly thereafter by each of the major powers.

After the conclusion of the war and the draconian aspects of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany launched various propaganda efforts to counter the imputation of guilt upon Germany by the victorious Allies, starting with the War Guilt Section (Kriegsschuldreferat), run by the Foreign Ministry (Auswartiges Amt). Two additional units were created in April 1921, in an effort to appear to be independent of the ministry: the Center for the Study of the Causes of the War (Zentralstelle zur Erforschung der Kriegsursachen), and the Working Committee of German Associations Arbeitsausschuss.[14][15]

War Guilt Section

The position of the SPD party majority, which was tied to its own approval of the war from 1914 to 1918 and left the imperial administrative apparatus almost untouched, continued to determine the domestic political reappraisal of the war.[16] With an eye to the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), that began on January 18, 1919, by late 1918 the Foreign Office had already established the "Bülow Special Office" (Spezialbüro von Bülow), named after former Reich Chancellor Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow and which had been set up after the armistice. It's role was to collect documents from various sources, including the Bolsheviks, for use by to counter the Allied allegations at Versailles. The documents collected by the Special Bureau were used in German negotiations in paris, as part of the "Professors' Memorandum" presented to the allies on 27 May 1919. It was probably written by von Bülow, but signed by the professors for "patriotic reasons".[17][18] In 1919, this became the "War Guilt Section" (Kriegsschuldreferat), and its purpose was to counter the war guilt accusation of the Allies. [17]

In the same way that color books did, the Office collected documents to counter accusations that Germany and Austria-Hungary had planned the world war and had "intentionally" disregarded the international law of war. This was also intended to provide foreign historians and journalists with exculpatory material to influence public opinion abroad.

The department also acted as an "internal censorship office", determined which publications were to be praised or criticized, and prepared official statements for the Reich Chancellor on the subject of war guilt.[19][page needed] Theodor Schieder later wrote about this: "In its origin, the research was virtually a continuation of the war by other means."[f][20]

However, documentation from the War Guilt Section was not considered by the delegates of the victorious powers at the Paris Conference or in the years that followed. The only concession from the Allies, was waiving their demand for extradition of the German "main war criminals" after 1922.[21]

Landsberg project

Center for the Study of the Causes of the War

The Center for the Study of the Causes of the War (Zentralstelle zur Erforschung der Kriegsursachen) was a "clearinghouse for officially desirable views on the outbreak of the war" and for circulating these views faster and more broadly. The Center was created by the War Guilt Section in order to bring to the public documents which would unify public opinion towards the official line. It was prolific, with Wegerer writing more than 300 articles.[22]

Arbeitsausschuss Deutscher Verbände

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

The Arbeitsausschuss Deutscher Verbände (Working Committee of German Associations.[23]

Dealing with the issue and responsibilities

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Potsdam Reichsarchiv

From 1914 on, the German army exerted a great influence on German historiography. The General Staff was responsible for writing war reports until 1918, when the Potsdam Reichsarchiv [fr; de], founded by Hans von Seeckt, took over. The Foreign Office conducted the historiography of the Weimar Republic in parallel with the Reichswehr and its administrative staff, who were largely opposed to democracy.

The Reichsarchiv also worked to refute German responsibility for the war, and for war crimes. To this end, it produced technical reports for the parliamentary commission and published eighteen volumes on the subject of "The First World War 1914–1918" from 1925 until it was taken over by the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv) in 1956. Until 1933, the methods of historical criticism used were:

- methodical interrogation of witnesses and analysis of reports from subordinate military services where collections of military mail become new historical sources.

- Some of the criticism of the Supreme Army Command, especially against Helmuth von Moltke and Erich von Falkenhayn, was officially admitted, which relieved their successors, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, of their responsibility.

- The primacy of government policy and the traditional German attraction to "great leaders" contradicts, in part unintentionally, the logic of the legend which arose from fateful forces, of non-responsibility for the war.

Nevertheless, some aspects remain to be studied, such as the influence of the economy, the masses, or ideology, on the course of the war. The evolution towards a "total war" is a concept that is still unknown.[24]

Acknowledging the question

While most of the German media denounced the treaty, others believed that the question of responsibility for the war should be dealt with at a moral level. One example was Die Weltbühne ("World Stage"), a left-liberal journal founded in November 1918. According to its editor, Siegfried Jacobsohn, it is absolutely necessary to expose the faults of pre-war German policy and to acknowledge responsibility in order to achieve a prosperous democracy and a retreat from militarism.

On 8 May 1919, a few days after the bloody repression of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, Heinrich Ströbel wrote in Die Weltbühne:

No, people in Germany are still far from any kind of recognition. Just as one refuses to acknowledge guilt, so also does one stubbornly refuse to believe in the good will of others. One still sees only greed, intrigue, and malice in others, and the most invigorating hope is that the day will come when these dark forces will be made to serve their own interests. The rulers of today still haven't learned anything from the world war; the old illusion, the old megalomania, still dominates them.[g]

Carl von Ossietzky and Kurt Tucholsky, contributors to the review, supported the same point of view. On 23 July 1919, Tucholsky wrote a review of Emil Ludwig's book July 14:

The people did not want war, no people wanted it; through the narrow-mindedness, negligence, and malice of the diplomats this "stupidest of all wars" has come about.[h]

— Kurt Tucholsky, cited in: Kritiken und Rezensionen, Gesammelte Schriften 1907-1935[25]

A pacifist movement was formed in the Weimar Republic, which demonstrated on 1 August, anti-war day. Its members came from different backgrounds: left-wing parties, liberal and anti-militarist groups, former soldiers, officers and generals. They took on the question of responsibility. The role of their women in their pacifist transformation is also worth noting. Among them: Hans-Georg von Beerfelde, Moritz von Egidy [fr; de], Major Franz Carl Endres [fr; de], the lieutenant captains Hans Paasche and Heinz Kraschutzki, Colonel Kurt von Tepper-Laski [fr; de], Fritz von Unruh but also Generals Berthold Deimling, Max von Montgelas and Paul von Schoenaich [fr; de].[26][better source needed]

At the first pacifist congress in June 1919, when a minority led by Ludwig Quidde repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, the German League for Human Rights and the Center for International Law [fr] made the question of responsibility a central theme. The independent Social Democrats and Eduard Bernstein were moving in the same direction and managed to change the representation put forward by the Social Democrats that war was a necessary condition for a successful social revolution. This led to the reunification of a minority of the party with the Social Democrats in 1924 and the inclusion of some pacifist demands in the 1925 Heidelberg Program [de; fr][citation needed]

Historians of the Sacred Union

Historians with minority views

Walter Fabian

Walter Fabian was a German journalist and social-democratic politician. In 1925, he published "The War Guilt Question" which examined the events that led to the war.[27] His book, although already out of print a year after publication, became one of the books banned after Adolf Hitler came to power.

Pre-war policy

You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (December 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Map of Bismarck's alliances

| |||||||||||

Fabian's first field of research was the domination of pre-war politics by Bismarck's politics of alliances [de; fr; es] (Bündnispolitik), which Fabian characterizes as "Europe's downfall".[i] The system of alliances set up in the summer of 1914 and its complexity made the outbreak of war inevitable. Otto von Bismarck had recognized the usefulness of this policy at the time;[28] Germany's central location in Europe pushed politicians like Bismarck to form alliances to avoid the nightmare scenario of possible encirclement.[29] After having ensured the neutrality of Russia and Austria-Hungary in 1881 with the singing of the League of the Three Emperors, the Reinsurance Treaty was signed in 1887. The isolation of France was the basis of Bismarckian policy in order to be able to ensure the security of the Reich.

The July Crisis and mobilization

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2020) |

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria served as a catalyst for war and "reflected the sharp tension that prevailed between Austria and Hungary for a number of years"[j] The carte blanche given by William II to the Austrian emperor had, according to Fabian, also other reasons, in particular the willingness of Germany to wage a preventive war[31] for fear of Russian mobilization. In marginal notes on a report by German ambassador Heinrich von Tschirschky, William II wrote "The situation with the Serbs must be dealt with, and quickly.[k] Walter Fabian judged the ultimatum addressed to Serbia to be impossible: "Austria wanted the ultimatum to be rejected; Germany, which according to Tirpitz already knew the main points of it on July 13, wanted the same thing."[33][l]

Fabian showed that Germany had an undeniable share of responsibility in the war. Even if the emperor and chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg tried to defuse events at the last moment, the army threw its full weight into the effort in order to force the situation. Chief of Staff von Molkte sent a telegram in which he stated that Germany would mobilize, but William II asserted that there was no longer any reason to declare war since Serbia accepted the ultimatum.[34] Various futile attempts at peace were made, such as the proposal of 27 July to hold a four-power conference.

Supremacy of the army

Further evolution

Erfüllungspolitik

After the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the German government was confronted with two possible approaches: resist the treaty, or execute it by putting in place the Erfüllungspolitik [de] (policy of appeasement). Some politicians showed that the war guilt question was not an insurmountable obstacle. Chancellor Joseph Wirth put in place the policy of appeasement by executing the treaty between May 1921 and November 1922.[35] This gave new impetus to diplomacy and improved the political and economic situation of the country. The Wirth government managed to obtain a revision of the treaty. The method used was simple: fulfill the clauses of the treaty in order to show their impossibility.[36] The war reparations that Germany had to pay weighed heavily on the economy. It amounted to two billion Gold marks and 26% of its export revenue.[37] By agreeing to pay this sum on 5 May 1921, Wirth demonstrated Germany's good faith. By applying the Erfüllungspolitik, Germany acknowledged part of its responsibility for the war, even though Wirth was indignant at the way the reparations policy was implemented. On 26 April 1922, the Treaty of Rapallo was signed, reducing Germany's isolation. However, the Erfüllungspolitik became one of the foundations of the smear campaign led by the ultranationalists. The execution of the treaty was considered treason.[38], and one of the proponents of this policy, Walther Rathenau, was assassinated on 24 June 1922 in Berlin. Matthias Erzberger had been murdered a year earlier.

Gustav Stresemann

By paving the way for other politicians, such as Gustav Stresemann, the Erfüllungspolitik [de] policy[m] (policy of appeasement) allowed Germany to regain a leading European diplomatic position. After the 1922 Treaty of Rapallo, Germany renewed contacts with other countries, such as the Soviet Union. The borders that were defined by the Treaty of Versailles were also at the heart of the grievances of the German government, which requested their revision.[39]

In October 1925, the Locarno Treaties were signed. They solved the problem of the borders, with Germany accepting the loss of Alsace-Lorraine and of Eupen-Malmedy, and in return Germany was assured that it would no longer be occupied by France. The war guilt question did not block its foreign policy. Stresemann, a man of compromise but above all a defender of German interests, succeeded in getting Germany to rejoin the League of Nations on 8 September 1926. If international relations were calmed, Franco-German relations were also calmed. Stresemann and Aristide Briand received the Nobel Peace Prize.[citation needed]

Decline of the Social Democrats

The refusal to admit the collapse of the German army gave way to the stab-in-the-back myth, which alleged that the government formed by the socialists betrayed the army by signing the armistice while still in a state of combat. German nationalism, incarnated by the defeated military, did not recognize the legitimacy of the Weimar Republic.[40] This legend weakened the Social Democratic Party through slander campaigns based on various allegations: namely, that the SDP not only betrayed the army and Germany by signing the armistice, but also repressed the Spartacist uprising, proclaimed the republic, and refused (for some of its members) to vote for war credits in 1914. Hindenburg spoke of the "division and relaxation of the will to victory"[n] driven by internal party interests. Socialists are labeled, the "Vaterlandslose" ("the homeless"). Hindenburg continued to emphasize the innocence of the army, stating: "The good core of the Army is not to blame. Its performance is as admirable as that of the officer corps.[o]

This slander had electoral consequences for the Social Democrats. In the 1920 election, the percentage of SPD seats in the Reichstag was 21.6 per cent, down from 38 per cent in 1919. Right-wing parties gradually gained ground, such as the German National People's Party (DNVP), which won 15.1 per cent of the seats compared to only 10.3 per cent in 1919. For five years, the SPD was absent from all governments between 30 November 1923 and 29 June 1928. According to Jean-Pierre Gougeon, the decline of the SPD was due to the fact that it had not sufficiently democratized the country since the proclamation of the Weimar Republic.[43] Judges, civil servants and high-ranking civil servants had not been replaced, and they often remained loyal to the emperor, all the more so since military propaganda blamed the republic for his abdication.

Rise of the National Socialists

In other countries

France

Britain

Soviet Union

United States

Austria

Post-World War II

West Germany

After the fall of the Nazi regime, conservative historians from the time of the Weimar Republic dominated the debates in West Germany by spreading the same theses as before.[44] For example, Gerhard Ritter wrote that "A politico-military situation held our diplomacy prisoner at the time of the great world crisis of July 1914."[45]

In Die deutsche Katastrophe, Friedrich Meinecke supports the same idea. Foreign research, such as that of the Italian Luigi Albertini, is not taken into account. In his three-volume critical work, published in 1942-1943 (Le origini della guerra del 1914), Albertini comes to the conclusion that all European governments had a share of responsibility in the outbreak of the war, while pointing to German pressure on Austria-Hungary as the decisive factor in the latter's bellicose behaviour in Serbia.[citation needed]

In September 1949, Ritter, who became the first president of the Union of German Historians [fr; de] stated in his opening statement that the fight against the war guilt question at the time of the Weimar Republic finally led to the worldwide success of German theses,[46] which he still maintained in his 1950 essay: "The German thesis that there could be no question of a long-prepared invasion of their neighbours by the Central Powers soon became generalized within the huge international specialist research community."[47]

Fischer controversy

The Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer was the first to research all accessible archive holdings according to the war aims of the Central Powers before and during the war. In October 1959 his essay about German war objectives was published.[48] Hans Herzfeld's [de] response in Historischen Zeitschrift (Historical Journal) marked the beginning of a controversy that lasted until about 1985 and permanently changed the national conservative consensus on the question of war guilt.

Fischer's book Germany's Aims in the First World War [49] drew conclusions from detailed analysis of the long-term causes of war and their connection the foreign and German colonial policy of Kaiser Wilhelm II.[50]

Given that Germany wanted, desired and covered up the Austrian-Serbian war and, trusting in German military superiority, deliberately chose to enter into conflict with Russia and France in 1914, the German Imperial leadership bears a considerable part of the historical responsibility for the outbreak of a general war.

Initially, right-wing conservative authors such as Giselher Wirsing accused Fischer of pseudo-history and, like Erwin Hölzle [de], tried to uphold the Supreme Army Command's hypothesis of Russian war guilt.[51] Imanuel Geiss supported Fischer in 1963–64 with a two-volume collection of documents, referring in it to the destruction of important files from the July crisis in Berlin shortly after the war.[52]

After a battle of speeches lasting several hours at the 1964 Historians' Day, Fischer's main rival Andreas Hillgruber conceded considerable responsibility of the German leadership under Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg for the outbreak of the war, but continued to deny the Empire's continuous striving for hegemony before and during the war.[53] Gerhard Ritter stuck to his view of a foreign policy "encirclement" (Einkreisung) of Germany by the Entente powers, which in his view, had rendered any German striving for hegemony as purely illusory adventurism.[54]

German-American historian Klaus Epstein [de] noted, when Fischer published his findings in 1961, that Fischer instantly rendered obsolete every book previously published on the subject of responsibility for the First World War, and German aims in that war.[55] Fischer's own position on German responsibility for World War I has become known as the "Fischer thesis."

Since around 1970, Fischer's work has stimulated increased research into the socio-economic causes of war. These include the orientation toward a war economy, the imperial monarchy's inability to reform domestic policy, and domestic competition over resources.

Contemporary research

See also

- 1930s

- Aftermath of World War I

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles

- Austria victim theory

- Causes of World War I

- American entry into World War I

- Austro-Hungarian entry into World War I

- British entry into World War I

- French entry into World War I

- German entry into World War I

- Italian entry into World War I

- Japanese entry into World War I

- Ottoman entry into World War I

- Russian entry into World War I

- History of the Balkans

- International relations (1814–1919)

- Paris Peace Conference, 1919

- Causes of World War II

- Centre for the Study of the Causes of the War

- Commission of Responsibilities

- Dawes Plan

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- European Civil War

- European interwar economy

- Fourteen Points

- German collective guilt

- German nationalism

- Germany's Aims in the First World War

- Golden Twenties

- Historiography of Germany

- Historiography of the causes of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Interwar period

- Manifesto of the Ninety-Three

- Neville Chamberlain's European Policy

- Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920)

- Propaganda in World War I

- Scheidemann cabinet

- Stab-in-the-back myth

- Timeline of events preceding World War II

- Treaty of Trianon

- Vergangenheitsbewältigung

- War of aggression

- "War of Illusions"

- Weimar culture

- Weltpolitik

- World Disarmament Conference

- World War I reparations

- Young Plan

References

{{cite journal |lang=de |journal= |last= |first= |last2= |first2= |title= |url= |publisher= |date= |volume= |issue= |issn= |oclc= |pages= |doi= |access-date= }}

{{cite book |lang=de |last1= |first1= |last2= |first2= |title= |trans-title= |date= |orig-year=1st pub. [[PUB]] (yyyy) |url= |page= |chapter= |trans-chapter= |location= |publisher= |isbn= |oclc= |access-date= |quote= }}

Notes

- ^ Clemenceau: ""L'heure est venue du lourd règlement de comptes."

- ^ Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, speaking to the Allies at Versailles in 1919: "Mais aussi dans la manière de faire la guerre l'Allemagne n'a pas commis seule des fautes, chaque nation en a commis. Je ne veux pas répondre aux reproches par des reproches, mais, si on nous demande de faire amende honorable, il ne faut pas oublier l'armistice."

- ^ Working Group for a Policy of Justice: "Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Politik des Rechts"; also known as the Heidelberger Vereinigung ("Heidelberg Association")

- ^ war guilt lie: Kriegsschuldlüge"

- ^ a b culpable individuals: "Kriegsschuldigen"

- ^ Theodor Schieder: "Die Forschung war im Ursprung geradezu eine Fortsetzung des Krieges mit anderen Mitteln."

- ^ Ströbel quotation: Nein, man ist in Deutschland noch weit ab von jeder Erkenntnis. Wie man das Schuldbekenntnis verweigert, so verweigert man auch dem guten Willen der Andern verstockt den Glauben. Man sieht noch immer nur die Gier, die Ränke, die Arglist der Andern, und die belebendste Hoffnung ist, daß dereinst der Tag komme, der diese dunklen Mächte den eigenen Interessen dienstbar mache. Noch haben die heute Regierenden nichts aus dem Weltkrieg gelernt, noch beherrscht sie der alte Wahn, der alte Machtwahn.

- ^ Die Völker haben keinen Krieg gewollt, kein Volk hat ihn gewollt; durch die Borniertheit, Fahrlässigkeit und Böswilligkeit der Diplomaten ist es zu diesem »dümmsten aller Kriege« gekommen.

- ^ Europe's downfall: "Europas Verhängnis".[28]

- ^ "Ausdruck der scharfen Spannung, die seit einer Reihe von Jahren zwischen Österreich-Ungarn herrschte." [30].

- ^ "Mit den Serben muss aufgeräumt werden und zwar bald."[32].

- ^ "Österreich wollte die Nichtannahme des Ultimatums, Deutschland, das laut Tirpitz bereits am 13. Juli die wichtigsten Punkte kannte, wollte das gleiche."[33]

- ^ "Erfüllungspolitiker": politicians advocating Erfüllungspolitik [de]: the politics of appeasement; that is, Germans who tried to make do with the harsh requirements of the Treaty of Versailles.

- ^ "Spaltung und Lockerung des Siegeswillens".[41]

- ^ "Den guten Kern des Heers trifft keine Schuld. Seine Leistung ist ebenso bewunderungswürdig wie die des Offizierkorps."[42]

- Footnotes

- ^ Thoss 1994, p. 1012-1039.

- ^ Traverso 2017.

- ^ "World War I – Killed, wounded, and missing". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Keegan 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Binkley & Mahr 1926, p. 399–400.

- ^ Morrow 2005, p. 290.

- ^ Treaty 1919, p. 1.

- ^ Longerich 1992, p. 142.

- ^ a b c Longerich 1992, p. 100.

- ^ Draeger 1934, p. 122.

- ^ Treaty 1919, p. 3.

- ^ Löwe, Teresa (2000). "II. Bernsteins Kampf für die Anerkennung der deutschen Kriegsschuld". Der Politiker Eduard Bernstein: eine Untersuchung zu seinem politischen Wirken in der Frühphase der Weimarer Republik (1918-1924). Gesprächskreis Geschichte, H. 40. (in German). Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Historisches Forschungszentrum. ISBN 978-3-86077-958-3. OCLC 802083353.

- ^ Geiss, Imanuel (1978). "16 Karl Liebknecht". Das Deutsche Reich und der Erste Weltkrieg. Reihe Hanser, 249. Munich; Vienna: Hanser. p. 205. ISBN 978-3-446-12495-0. OCLC 604904798.

- ^ Wittgens 1980, p. 229–237.

- ^ Mombauer 2013, p. 53.

- ^ Niemann, Heinz (2015). "Die Debatte um Kriegsursachen und Kriegsschuld in der deutschen Sozialdemokratie zwischen 1914 und 1924" [The Debate on the Causes of War and War Guilt in German Social Democracy between 1914 and 1924]. JahrBuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung (in German). 14 (1). Förderverein für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung: 54–66. ISSN 1610-093X. OCLC 915569817.

- ^ a b Mombauer 2013, p. 51.

- ^ John Horne; Alan Kramer (2001). German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. Yale University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-300-10791-3.

- ^ Geiss 1978. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGeiss1978 (help)

- ^ Frie 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Altmann & Scriba 2014.

- ^ Wittgens 1980, p. 229, 232–233.

- ^ Wittgens 1980, p. 236–237.

- ^ Ackerman, Volker (13 May 2004). "Sammelrez: Literaturbericht: 'Erster Weltkrieg' - H-Soz-u-Kult / Rezensionen / Bücher" [Omnibus review: Literature report: 'First World War' - H-Soz-u-Cult / Reviews / Books] (PDF). H-Soz-u-Kult (in German). Berlin: Clio-online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Tucholsky, Kurt. "Tucholsky - Krieg: Juli 14 - Emil Ludwig (Kritiken und Rezensionen)" [Tucholsy - War: Juli 14 - Emil Ludwig (Reviews and critiques)] (in German).

- ^ Strutynski, Peter (9 August 2000). "Vom Offizier zum Pazifisten Von Wolfram Wette (Freiburg)" [From Officer to Pacifist by Wolfram Wette (Freiburg)]. Uni Kassel (in German). Archived from the original on 24 October 2008.

- ^ Fabian 1926.

- ^ a b Fabian 1926, p. 20.

- ^ Isaac 1933, p. 26-27.

- ^ Fabian 1926, p. 36.

- ^ Fabian 1926, p. 46.

- ^ German Foreign Office 1919, p. 11.

- ^ a b Fabian 1926, p. 43.

- ^ Fabian 1926, p. 68.

- ^ Krüger 1985, p. 132.

- ^ Krüger 1985, p. 133.

- ^ Poidevin 1972, p. 269.

- ^ Rovan 1999, p. 596.

- ^ Krüger 1985, p. 213.

- ^ Von Mises 1947, p. 268.

- ^ Longerich 1992, p. 134.

- ^ Longerich 1992, p. 135.

- ^ Gougeon 1996, p. 226.

- ^ Geiss 1978, p. 107. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGeiss1978 (help)

- ^ Ritter 1960, p. 171.

- ^ Ritter 1950, p. 16.

- ^ Ritter 1950, p. 92.

- ^ Fischer 1959.

- ^ Fischer 1971.

- ^ Fischer 1971, p. 97.

- ^ Köster, Freimut (22 September 2004). "Unterrichtsmaterial zur Fischer-Kontroverse" [Teaching materials on the Fischer Controversy] (in German). Berlin: Humboldt University.

- ^ Geiss, Imanuel (1963). Julikrise und Kriegsausbruch 1914: Dokumentensammlung [The July Crisis and Outbreak of the 1914 War: Document Collection] (in German). Hanover: Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen. OCLC 468874551., cited in: Gasser, Adolf (1985). Preussischer Militärgeist und Kriegsentfesselung 1914: drei Studien zum Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges [Prussian Military Spirit and Unleashing War in 1914: Three Studies on the Outbreak of the First World War] (in German). Frankfurt: Helbing & Lichtenhahn. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-7190-0903-8. OCLC 610859897.

- ^ Hillgruber, Andreas; Hillgruber, Karin (1979). Deutschlands Rolle in der Vorgeschichte der beiden Weltkriege. Kleine Vandenhoeck-Reihe, 1458. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 56f. ISBN 978-3-525-33440-9. OCLC 243427381.

- ^ Ritter, Gerhard (1964). Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk: Die Tragödie der Staatkunst: Bethmann Hollweg als Kriegskanzler 1914-1917. Munich: R. Oldenbourg. p. 15. OCLC 889047603.

- ^ Epstein, Klaus. "Review: German War Aims in the First World War," World Politics, Volume 15, Issue #1, (October 1962), p. 170.

Works cited

- Altmann, Gerhard; Scriba, Arnulf (14 September 2014). "LeMO Kapitel - Weimarer Republik - Innenpolitik - Kriegsschuldreferat" [Weimar Republic Domestic policy - War Guilt Section]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German).

- Binkley, Robert C.; Mahr, Dr. A. C. (June 1926). "A New Interpretation of the "Responsibility" Clause in the Versailles Treaty". Current History. 24 (3): 398–400.

- Walter Fabian (1985) [1926]. Die Kriegsschuldfrage. Grunsätzliches und Tatsächliches zu ihrer Lösung [The War Guilt Question. Basic and Factual Information on its Solution] (in German). Leipzig: 1. Auflage. ISBN 3-924444-08-0.

- Fischer, Fritz (1959). Deutsche Kriegsziele Revolutionierung und Separatfrieden im Osten, 1914-1918 [German War Aims – Revolutionization and Separate Peace in the East, 1914-1918] (in German). Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag. OCLC 21427726.

- Frie, Ewald (2004). Das Deutsche Kaiserreich. Kontroversen um die Geschichte (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-14725-0. OCLC 469341132.

- Geiss, Immanuel (1978). "Die Kriegsschuldfrage - das Ende eines nationalen Tabus" [The War Guilt Question - the End of a National Taboo]. Das Deutsche Reich und die Vorgeschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs [The German Reich and the Background of the First World War] (in German). Vienna.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Gougeon, Jacques-Pierre (1996). La social-démocratie allemande, 1830-1996: de la révolution au réformisme [The German Social Democracy, 1830-1996; from Revolution to Reform]. Histoires. Paris: Aubier. ISBN 978-2-7007-2270-3. OCLC 410241884.

- Isaac, Jules (1933). Un débat historique: le problème des origines de la guerre [A Historic Debate: the Problem of the Origins of the War]. Paris: Rieder. OCLC 487772456.

Keegan, John (1998). The First World War. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-180178-6. OCLC 1167992766.

- Krüger, Peter (1985). Die Aussenpolitik der Republik von Weimar [Foreign Policy of the Weimar Republic] (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-07250-7. OCLC 1071412383.

- Longerich, Peter (1992). Die Erste Republik. Dokumente zur Geschichte des Weimarer Staates [The First Republic. Documents on the history of the Weimar State] (in German). Munich: Piper.

- Mombauer, Annika (2 December 2013). "The German 'innocence campaign'". The Origins of the First World War: Controversies and Consensus. Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87584-0. OCLC 864746118.

- Morrow, John H. (2005). The Great War: An Imperial History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20440-8.

- Poidevin, Raymond (1972). L'Allemagne de Guillaume II à Hindenburg, 1900-1933 [Germany of WIlliam II at Hindenburg, 1900-1933]. L'Univers Contemporain, 4 (in French). Éditions Richelieu. OCLC 857948335.

- Ritter, Gerhard (1950). "Gegenwärtige Lage und Zukunftsaufgaben deutscher Geschichtswissenschaft" [Present Situation and Future Tasks of German Historiography]. Historische Zeitschrift (in German). 170.

- Ritter, Gerhard (1960). Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Vol. 2. Munich.

Militärisch-politische Zwangslage, die unsere Diplomatie im Moment der großen Weltkrisis im Juli 1914 geradezu in Fesseln schlug.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Rovan, Joseph (1999). Histoire de l'Allemagne: des origines à nos jours. Points Histoire. Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2020351362. OCLC 1071615619.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Thoß, Bruno (1994). "Der Erste Weltkrieg als Ereignis und Erlebnis. Paradigmenwechsel in der westdeutschen Weltkriegsforschung seit der Fischer-Kontroverse" [The First World War as event and experience. Paradigm Shift in West German World War Research since the Fischer Controversy]. In Wolfgang Michalka (ed.). Der Erste Weltkrieg: Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, Analyse [The First World War : impact, awareness, analysis]. Piper Series (in German). Munich: Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-11927-6. OCLC 906656746.

- Traverso, Enzo (7 February 2017) [1st pub. Stock (2007)]. Fire and Blood: The European Civil War, 1914-1945. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-78478-136-1. OCLC 999636811.

- Von Mises, Ludwig (1947) [1st pub. 1944 Yale Univ Press]. Le gouvernement omnipotent de l'état totalitaire à la guerre totale [Omnipotent government the rise of the total state and total war] (in French). Paris: Éditions politiques, économiques et sociales. OCLC 1131212956.

- Wittgens, Herman J. (1980). "War Guilt Propaganda Conducted by the German Foreign Ministry During the 1920s". Historical Papers / Communications historiques. 15 (1). Canadian Historical Association: 228–247. doi:10.7202/030859ar. ISSN 0068-8878. OCLC 1159619139.

Sources

- Pre-WW I events

- Jacques Benoist-Méchin, Histoire de l'Armée allemande, Robert Laffont, Paris, 1984. (in French)

- Volker Berghahn, Der Erste Weltkrieg (Wissen in der Beck´schen Reihe). C.H. Beck, München 2003, ISBN 3-406-48012-8 (in German)

- Jean-Pierre Cartier, Der Erste Weltkrieg, Piper, München 1984. ISBN 3-492-02788-1 (in German)

- Jacques Droz [fr; de], Les Causes de la Première Guerre mondiale. Essai d'historiographie, Paris, 1997. (in French)

- Niall Ferguson, Der falsche Krieg; DVA, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-421-05175-5 (in German)

- Fischer, Fritz (1971) [1st pub: 1961]. Griff nach der Weltmacht : die Kriegszielpolitik des kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914/18 [Reaching for World Power : The War Aims Policy of Imperial Germany 1914/18] (in German) (3rd ed.). Dusseldorf: Droste. OCLC 1154200466..

- Fischer, Fritz (1970). Les Buts de guerre de l’Allemagne impériale (1914-1918) (in French). Translated by Geneviève Migeon et Henri Thiès (fr:Référence:Les Buts de guerre de l'Allemagne impériale (Fritz Fischer)#Tr.C3.A9vise 1970 ed.). Paris: Éditions de Trévise.

- Imanuel Geiss, Der lange Weg in die Katastrophe, Die Vorgeschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges 1815–1914, Piper, München 1990, ISBN 3-492-10943-8 (in German)

- James Joll, Gordon Martel: The Origins of the First World War Longman 2006, ISBN 0-582-42379-1 (in English)

- Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860–1914; Allen & Unwin, London 1980, ISBN 1-57392-301-X (in English)

- Robert K. Massie, Die Schalen des Zorns. Großbritannien, Deutschland und das Heraufziehen des Ersten Weltkrieges, Frankfurt/Main (S. Fischer) 1993, ISBN 3-10-048907-1 (in German)

- Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Die Urkatastrophe Deutschlands. Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918 (= Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte 17). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-608-60017-5 (in German)

- Sönke Neitzel, Kriegsausbruch. Deutschlands Weg in die Katastrophe 1900-1914, München 2002, ISBN 3-86612-043-5 (in German)

- Pierre Renouvin, Les Buts de guerre du gouvernement français. 1914-1915, in Revue historique 1966

- Pierre Renouvin, Les Origines immédiates de la guerre, Paris, 1925

- Pierre Renouvin, La Crise européenne et la Grande Guerre, Paris, 1939

- Gerhard Ritter, Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Band 3: Die Tragödie der Staatskunst München, 1964 (in German)

- Volker Ullrich, Die nervöse Großmacht. Aufstieg und Untergang des deutschen Kaiserreichs 1871–1918, Frankfurt/Main (S. Fischer) 1997, ISBN 3-10-086001-2 (in German)

- Contemporary publications from the Weimar Republic

- Collectif (1919). Traité de Versailles 1919 [Treaty of Versailles 1919] (in French). Nancy: Librairie militaire Berger Levrault.

- Camille Bloch/Pierre Renouvin, « L'article 231 du traité de Versailles. Sa genèse et sa signification », in Revue d'Histoire de la Guerre mondiale, janvier 1932

- Draeger, Hans (1934). Anklage und Widerlegung. Taschenbuch zur Kriegsschuldfrage [Charge and rebuttal. Pocket edition on the question of war guilt.] (in German). Berlin: Arbeitsausschuss Deutscher Verbände. OCLC 934736076.

- Hajo Holborn, Kriegsschuld und Reparationen auf der Pariser Friedenskonferenz von 1919, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig/Berlin 1932 (in German)

- Heinrich Kanner, Der Schlüssel zur Kriegsschuldfrage, München 1926 (in German)

- Max Graf Montgelas, Leitfaden zur Kriegsschuldfrage, W. de Gruyter & co. Berlin/Leipzig 1923 (in German)

- fr:Mathias Morhardt, Die wahren Schuldigen. Die Beweise, das Verbrechen des gemeinen Rechts, das diplomatische Verbrechen, Leipzig 1925 (in German)

- Raymond Poincaré/René Gerin, Les Responsabilités de la guerre. Quatorze questions par René Gerin. Quatorze réponses par Raymond Poincaré., Payot, Paris, 1930

- Heinrich Ströbel, Der alte Wahn, dans : Weltbühne 8 mai 1919 (in German)

- Max Weber,Zum Thema der „Kriegsschuld“, 1919; Zur Untersuchung der Schuldfrage, 1919 (in German)

- Debate descriptions

- Fritz Dickmann, Die Kriegsschuldfrage auf der Friedenskonferenz von Paris 1919, München 1964 (Beiträge zur europäischen Geschichte 3) (in German)

- Michael Dreyer, Oliver Lembcke, Die deutsche Diskussion um die Kriegsschuldfrage 1918/19, Duncker & Humblot GmbH (1993), ISBN 3-428-07904-3 (in German)

- Jacques Droz, L'Allemagne est-elle responsable de la Première Guerre mondiale ?, in L'Histoire, No. 72, novembre 1984

- Sidney B. Fay, The Origins of the World War, 2 Bände, New York 1929 (in English)

- Hermann Kantorowicz, Imanuel Geiss, Gutachten zur Kriegsschuldfrage 1914, Europäische Verlagsanstalt 1967, ASIN B0000BRV2R (in German)

- Hahn, Eric J. C.; Carole Fink; Isabell V. Hull; MacGregor Knox (1985). "The German Foreign Ministry and the Question of War Guilt in 1918–1919". German Nationalism and the European Response 1890–1945. London: Norman. pp. 43–70.

- Ulrich Heinemann (1983). Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft (in German). Vol. 59. Die verdrängte Niederlage. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Kriegsschuldfrage in der Weimarer Republik. Gœttingue: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-647-35718-8.

- Georges-Henri Soutou, L'Or et le Sang. Les Buts de guerre économiques de la Première Guerre mondiale, Fayard, Paris, 1989

- Fischer Controversy

- Volker Berghahn, "Die Fischer-Kontroverse - 15 Jahre danach", in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 6 (1980), pp. 403-419. (in German)

- Geiss, Imanuel (1972). "Die Fischer-Kontroverse. Ein kritischer Beitrag zum Verhältnis zwischen Historiographie und Politik in der Bundesrepublik". In Geiss, Imanuel (ed.). Studien über Geschichte und Geschichtswissenschaft (in German). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. pp. 108–198..

- Klaus Große Kracht, Die zankende Zunft. Historische Kontroversen in Deutschland nach 1945, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-525-36280-3 (Recension de Manfred Kittel, Institut für Zeitgeschichte, München-Berlin) (in German)

- Wolfgang Jäger, Historische Forschung und politische Kultur in Deutschland. Die Debatte 1914–1980 über den Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkrieges, Göttingen 1984. (in German)

- Konrad H. Jarausch, Der nationale Tabubruch. Wissenschaft, Öffentlichkeit und Politik in der Fischer-Kontroverse, dans : Martin Sabrow, Ralph Jessen, Klaus Große Kracht (Hrsg.): Zeitgeschichte als Streitgeschichte. Große Kontroversen seit 1945, Beck 2003, ISBN 3406494730 (in German)

- John Anthony Moses, The Politics of Illusion. The Fischer Controversy in German Historiography, London 1975 (Nachdruck 1985), ISBN 0702210404 (in English)

- Gregor Schöllgen, Griff nach der Weltmacht? 25 Jahre Fischer-Kontroverse, dans : Historisches Jahrbuch 106 (1986), pp. 386-406. (in German)

- Matthew Stibbe, The Fischer Controversy over German War Aims in the First World War and its Reception by East German Historians, 1961–1989. Dans : The Historical Journal 46/2003, pp. 649–668. (in English)

- Recent analyses

- Jean-Jacques Becker (2004). L'année 14 (in French). Paris: A. Colin. ISBN 978-2-200-26253-2. OCLC 300279286..

- Jean-Baptiste Duroselle (2003). La Grande Guerre des Français 1914-1918 (in French). Perrin.

- Stig Förster (dir.), An der Schwelle zum Totalen Krieg. Die militärische Debatte über den Krieg der Zukunft 1919–1939 (= Krieg in der Geschichte 13). Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-74482-8 (in German)

- Jürgen Förster, Geistige Kriegführung in Deutschland 1919-1945 (in German)

- Ewald Frie (2004). Das Deutsche Kaiserreich (in German). Darmstadt.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - David Fromkin et William-Oliver Desmond, Le Dernier Été de l'Europe : Qui a déclenché la Première Guerre mondiale ?, Paris, 2004 ISBN 978-2246620716

- Christoph Gnau, Die deutschen Eliten und der Zweite Weltkrieg, PapyRossa-Verlag, Köln 2007, ISBN 978-3-89438-368-8 (in German)

- Krumeich, Gerd [in French] (2019). L'Impensable Défaite. L’Allemagne déchirée. 1918–1933. Histoire (in French). Paris: Belin. ISBN 978-2-7011-9534-6.

- Anne Lipp (2003). Meinungslenkung im Krieg. Kriegserfahrungen deutscher Soldaten und ihre Deutung 1914–1918 (in German). Gœttingue: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-35140-2.

- Markus Pöhlmann, Kriegsgeschichte und Geschichtspolitik: Der Erste Weltkrieg. Die amtliche Militärgeschichtsschreibung 1914–1956 (= Krieg in der Geschichte 12). Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-74481-X (in German)

- Jörg Richter, Kriegsschuld und Nationalstolz. Politik zwischen Mythos und Realität, Katzmann, 2003 (in German)

- Bruno Thoß et Hans-Erich Volkmann (dir.), Erster Weltkrieg – Zweiter Weltkrieg: Ein Vergleich. Krieg, Kriegserlebnis, Kriegserfahrung in Deutschland. Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-79161-3 (in German)

- Other aspects

- Gerhard Besier, Krieg - Frieden - Abrüstung. Die Haltung der europäischen und amerikanischen Kirchen zur Frage der deutschen Kriegsschuld 1914-1933, Göttingen 1982 (in German)

- Britta Bley, Wieviel Schuld verträgt ein Land? CD-ROM, Fachverlag für Kulturgeschichte und deren Vermittlung, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-938360-00-3 (in German)

- Von Mises, Ludwig (1944). Omnipotent government the rise of the total state and total war. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press. OCLC 248739093.

Further reading

- Jörg Richter, Kriegsschuld und Nationalstolz. Politik zwischen Mythos und Realität, Katzmann, 2003

- Mombauer, Annika. "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I." Central European History 48.4 (2015): 541-564.

- Annika Mombauer (2016). "Germany and the Origins of the First World War". In Matthew Jefferies (ed.). The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317043218.

- Karl Jaspers (2009). "The German Questions". The Question of German Guilt. ISBN 9780823220632.

- Karl Max Lichnowsky (Fürst von); Gottlieb von Jagow (2008) [1918]. The Guilt of Germany for the War of German Aggression : Prince Karl Lichnowsky's Memorandum; Being the Story of His Ambassadorship at London from 1912 to August, 1914, Together with Foreign Minister Von Jagow's Reply. F.P. Putnam (original), University of Wisconsin - Madison (digital).