Hangul: Difference between revisions

Kwamikagami (talk | contribs) →History: yeah, this figure is ridiculous |

→External links: restore very important link, which should not have been removed |

||

| Line 594: | Line 594: | ||

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1100.pdf Jamo in Unicode]|196 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 201612 bytes -->}} |

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1100.pdf Jamo in Unicode]|196 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 201612 bytes -->}} |

||

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UAC00.pdf Hangul syllables]|4.05 [[Mebibyte|MiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 4248838 bytes -->}} |

* {{PDFlink|[http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UAC00.pdf Hangul syllables]|4.05 [[Mebibyte|MiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 4248838 bytes -->}} |

||

* [http://sources.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Hangul_syllables List of syllables and Romanization]: [[Wikisource]] |

|||

[[Category:Hangul| ]] |

[[Category:Hangul| ]] |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 16 October 2007

| Hangul (한글) or Chosŏn'gŭl (조선글) [1] | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

| Creator | King Sejong |

Time period | 1443 to the present |

| Direction | Left-to-right, vertical right-to-left |

| Languages | Korean |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hang (286), Hangul (Hangŭl, Hangeul) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Hangul |

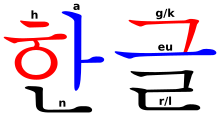

Hangul () is the native alphabet of the Korean language, as distinguished from the logographic Sino-Korean hanja system. It is the official script of North Korea, South Korea and the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture of China.

Hangul is a phonemic alphabet organized into syllabic blocks. Each block consists of at least two of the 24 Hangul letters, (jamo), with at least one each of the 14 consonants and 10 vowels. These syllabic blocks can be written horizontally from left to right as well as vertically from top to bottom, columns from right to left. Originally, the alphabet had several additional letters (see obsolete jamo). For a phonological description of the letters, see Korean phonology.

|

| Korean writing systems |

|---|

| Hangul |

|

| Hanja |

| Mixed script |

| Braille |

| Transcription |

| Transliteration |

Names

written in Hangul

| Hangul | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 한글 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 조선글 | ||||||

| Hanja | 朝鮮글 | ||||||

| |||||||

Official names

- The modern name Hangul (한글) is a term coined by Ju Sigyeong in 1912 that simultaneously means "great(한) script(글)" in archaic Korean and "Korean script" in modern Korean. It is not sino-Korean and therefore has no corresponding Hanja. 한글 is pronounced /hangɯl/ and would be romanized in one of the following ways:

- Hangeul or Han-geul in the Revised Romanization of Korean, which the South Korean government uses in all English publications and encourages for all purposes. Many recent publications have adopted this spelling.

- Han'gŭl in the older McCune-Reischauer system. When used as an English word, it is rendered without the diacritics: Hangul, or sometimes without capitalization: hangul. This is how it appears in many English dictionaries.

- Hankul in Yale Romanization, another common system in English dictionaries.

- North Koreans prefer to call it Chosŏn'gŭl (조선글), for reasons related to the different names of Korea.

- The original name was Hunmin Jeong-eum (훈민정음; 訓民正音; see history). Due to objections to the names Hangeul, Chosŏn'gŭl, and Urigeul (우리글) (see below) by the Korean minority in Manchuria, the otherwise uncommon short form Jeongeum may be used as a neutral name in some international contexts.

Other names

Until the early twentieth century, Hangul was denigrated as vulgar by the literate elite who preferred the traditional Hanja writing system. They gave it such names as:

- Eonmun (언문 諺文 "vernacular script").

- Amkeul (암클 "women's script"). 암 is a prefix that signifies a noun is feminine (수 is its counterpart).

- Ahae(t)geul (아햇글 or 아해글 "children's script").

- Achimkul ("writing you can learn within a morning")[2].

However, these names are now archaic, as the use of hanja in writing has become very rare in South Korea and completely phased out in North Korea. Today, the name Urigeul / Urigŭl (우리글) or "our script" is used in both North and South Korea in addition to Hangeul/Han'gŭl.

History

Hangul was promulgated by the fourth king of the Joseon Dynasty, Sejong the Great. Some suspect that such a complex project must have been developed by a team of researchers, and there appear to have been several people involved. For example, the Hall of Worthies is usually credited for the work. However, records show that his staff of scholars denounced the king for not having consulted with them. King Sejong and his team may have worked in secret because of the opposition by the educated elite.

The project was completed in late 1443 or early 1444, and published in 1446 in a document titled Hunmin Jeongeum ("The Proper Sounds for the Education of the People"), after which the alphabet itself was named. The publication date of the Hunmin Jeong-eum, October 9, became Hangul Day in South Korea. Its North Korean equivalent is on January 15.

It had been rumored that King Sejong visualized the written characters after studying an intricate lattice, but this speculation was put to rest by the discovery in 1940 of the 1446 Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye ("Explanations and Examples of the Hunmin Jeong-eum"). This document explains the design of the consonant letters according to articulatory phonetics and the vowel letters according to the principles of yin and yang and vowel harmony.

King Sejong explained that he created the new script because the Korean language was different from Chinese; using Chinese characters (the Hanja) to write was so difficult for the common people that only the male aristocrats (yangban) could read and write fluently. (A few female members of the royal family could also do so to a certain extent). The majority of Koreans were effectively illiterate before Hangul's invention.

Hangul was designed so that even a commoner could learn to read and write; the Haerye says "A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days."[3]

Hangul faced heavy opposition by the literate elite, such as Choe Manri and other Confucian scholars in the 1440s, who believed hanja to be the only legitimate writing system. Later rulers too became hostile to Hangul. Yeonsangun, the 10th king, forbade the study or use of Hangul and banned Hangul documents in 1504, and King Jungjong abolished the Ministry of Eonmun in 1506. In any case, until this time Hangul had been principally used by women and the undereducated.

The 16th century saw a revival of Hangul, with gasa literature and later sijo flourishing. In the 17th century, Hangul novels became a major genre. [4]

Due to growing Korean nationalism in the 19th century, Japan's attempt to sever Korea from China's sphere of influence, and the Gabo Reformists' push, Hangul was eventually adopted in official documents for the first time in 1894. Elementary school texts began using Hangul in 1895, and the Dongnip Sinmun, established in 1896, was one of the first newspapers printed exclusively in Hangul.[5]

After Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910, Hangul was taught in Japanese-established schools,[6] and Korean was written in a mixed Hanja-Hangul script, where most lexical roots were written in Hanja and grammatical forms in Hangul. Hangul orthography was standardized under Japanese rule by an academic group led by Ju Sigyeong in publications such as the Standardized System of Hangul in 1933, and a system for transliterating foreign orthographies was published in 1940. However, the Korean language, and with it Hangul, was banned from schools in 1938 as part of a policy of cultural assimilation. [7]

Since regaining independence from Japan in 1945, the Koreas have used Hangul or mixed Hangul as their sole official writing system, with ever-decreasing use of hanja. Since the 1950s, it has become uncommon to find hanja in commercial or unofficial writing in the South, with some South Korean newspaper only using hanja as abbreviations in headlines, to avoid ambiguity in homonyms, and elsewhere where space is limited. There has been widespread debate as to the future of Hanja in South Korea, and the number of characters taught in schools has fallen from ? in 1956 to 1,800 in the 1990s. North Korea reinstated Hangul as its exclusive writing system in 1949, and banned the use of Hanja completely.

Jamo

Jamo (자모; 字母) or natsori (낱소리) are the units that make up the Hangul alphabet. Ja means letter or character, and mo means mother, so the name suggests that the jamo are the building-blocks of the script.

There are 51 jamo, of which 24 are equivalent to letters of the Latin alphabet. The other 27 jamo are clusters of two or sometimes three of these letters. Of the 24 simple jamo, fourteen are consonants (ja-eum 자음, 子音 "child sounds") and ten are vowels (mo-eum 모음, 母音 "mother sounds"). Five of the simple consonant letters are doubled to form the five "tense" (faucalized) consonants (see below), while another eleven clusters are formed of two different consonant letters. The ten vowel jamo can be combined to form eleven diphthongs. Here is a summary:

- 14 simple consonant letters: ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄷ, ㄹ, ㅁ, ㅂ, ㅅ, ㅇ, ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, ㅎ, plus obsolete ㅿ (alveolar), ㆁ (velar), ㆆ, ㅱ, ㅸ, ㆄ

- 5 double letters (glotalized): ㄲ, ㄸ, ㅃ, ㅆ, ㅉ, plus obsolete ㅥ, ㆀ, ㆅ, ㅹ

- 11 consonant clusters: ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄶ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ, ㄽ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅀ, ㅄ, plus obsolete ㅦ, ㅧ, ㅨ, ㅪ, ㅬ, ㅭ, ㅮ, ㅯ, ㅰ, ㅲ, ㅳ, ㅶ, ㅷ, ㅺ, ㅻ, ㅼ, ㅽ, ㅾ, ㆂ, ㆃ and obsolete triple clusters ㅩ, ㅫ, ㅴ, ㅵ

- 6 simple vowel letters: ㅏ, ㅓ, ㅗ, ㅜ, ㅡ, ㅣ, plus obsolete ㆍ

- 4 simple iotized vowel letters (semi consonant-semi vowel): ㅑ, ㅕ, ㅛ, ㅠ

- 11 diphthongs: ㅐ, ㅒ, ㅔ, ㅖ, ㅘ, ㅙ, ㅚ, ㅝ, ㅞ, ㅟ, ㅢ, plus obsolete ㆎ, ㆇ, ㆈ, ㆉ, ㆊ, ㆋ, ㆌ

Four of the simple vowel jamo are derived by means of a short stroke to signify iotation (a preceding i sound): ㅑ ya, ㅕ yeo, ㅛ yo, and ㅠ yu. These four are counted as part of the 24 simple jamo because the iotating stroke taken out of context does not represent y. In fact, there is no separate jamo for y.

Of the simple consonants, ㅊ chieut, ㅋ kieuk, ㅌ tieut, and ㅍ pieup are aspirated derivatives of ㅈ jieut, ㄱ giyeok, ㄷ digeut, and ㅂ bieup, respectively, formed by combining the unaspirated letters with an extra stroke.

The doubled letters are ㄲ ssang-giyeok (kk: ssang- 쌍 "double"), ㄸ ssang-digeut (tt), ㅃ ssang-bieup (pp), ㅆ ssang-siot (ss), and ㅉ ssang-jieut (jj). Double jamo do not represent geminate consonants, but rather a "tense" phonation.

Jamo design

Hangul is a featural script. Scripts may transcribe languages at the level of morphemes (logographic scripts like hanja), of syllables (syllabic scripts like kana), or of segments (alphabetic scripts like the one you're reading here). Hangul goes one step further, using distinct strokes to indicate distinctive features such as place of articulation (labial, coronal, velar, or glottal) and manner of articulation (plosive, nasal, sibilant, aspiration) for consonants, and iotation (a preceding i- sound), harmonic class, and I-mutation for vowels.

For instance, the consonant jamo ㅌ t [tʰ] is composed of three strokes, each one meaningful: the top stroke indicates ㅌ is a plosive, like ㆆ ’, ㄱ g, ㄷ d, ㅂ b, ㅈ j, which have the same stroke (the last is an affricate, a plosive-fricative sequence); the middle stroke indicates that ㅌ is aspirated, like ㅎ h, ㅋ k, ㅍ p, ㅊ ch, which also have this stroke; and the curved bottom stroke indicates that ㅌ is coronal, like ㄴ n, ㄷ d, and ㄹ l. Two consonants, ㆁ and ㅱ, have dual pronunciations, and appear to be composed of two elements, stacked one over the other, to represent these two pronunciations: [ŋ]/silence for ㆁ and [m]/[w] for obsolete ㅱ.

With vowel jamo, a short stroke connected to the main line of the letter indicates that this is one of the vowels which can be iotated; this stroke is then doubled when the vowel is iotated. The position of the stroke indicates which harmonic class the vowel belongs to, "light" (top or right) or "dark" (bottom or left). In modern jamo, an additional vertical stroke indicates i-mutation, deriving ㅐ [ɛ], ㅔ [e], ㅚ [ø], and ㅟ [y] from ㅏ [a], ㅓ [ʌ], ㅗ [o], and ㅜ [u]. However, this is not part of the intentional design of the script, but rather a natural development from what were originally diphthongs ending in the vowel ㅣ [i]. Indeed, in many Korean dialects[citation needed], including the standard dialect of Seoul, some of these may still be diphthongs.

Although the design of the script may be featural, for all practical purposes it behaves as an alphabet. The jamo ㅌ isn't read as three letters coronal plosive aspirated, for instance, but as a single consonant t. Likewise, the former diphthong ㅔ is read as a single vowel e.

Beside the jamo, Hangul originally employed diacritic marks to indicate pitch accent. A syllable with a high pitch was marked with a dot (·) to the left of it (when writing vertically); a syllable with a rising pitch was marked with a double dot, like a colon (:). These are no longer used. Although vowel length was and still is phonemic in Korean, it was never indicated in Hangul, except that syllables with rising pitch (:) necessarily had long vowels.

Although some aspects of Hangul reflect a shared history with the Phagspa script, and thus Indic phonology, such as the relationships among the homorganic jamo and the alphabetic principle itself, other aspects such as organization of jamo into syllablic blocks, and which Phagspa letters were chosen to be basic to the system, reflect the influence of Chinese writing and phonology.

Consonant jamo design

The letters for the consonants fall into five homorganic groups, each with a basic shape, and one or more letters derived from this shape by means of additional strokes. In the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye account, the basic shapes iconically represent the articulations the tongue, palate, teeth, and throat take when making these sounds.

| Simple | Aspirated | Doubled |

|---|---|---|

| ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅉ |

| ㄱ | ㅋ | ㄲ |

| ㄷ | ㅌ | ㄸ |

| ㅂ | ㅍ | ㅃ |

| ㅅ | ㅆ |

The Korean names for the groups are taken from Chinese phonetics:

- Velar consonants (아음, 牙音 a-eum "molar sounds")

- ㄱ g [k], ㅋ k [kʰ]

- Basic shape: ㄱ is a side view of the back of the tongue raised toward the velum (soft palate). (For illustration, access the external link below.) ㅋ is derived from ㄱ with a stroke for the burst of aspiration.

- Coronal consonants (설음, 舌音 seol-eum "lingual sounds"):

- ㄴ n [n], ㄷ d [t], ㅌ t [tʰ], ㄹ r [ɾ, l]

- Basic shape: ㄴ is a side view of the tip of the tongue raised toward the alveolar ridge (gum ridge). The letters derived from ㄴ are pronounced with the same basic articulation. The line topping ㄷ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The middle stroke of ㅌ represents the burst of aspiration. The top of ㄹ represents a flap of the tongue.

- Bilabial consonants (순음, 唇音 sun-eum "labial sounds"):

- ㅁ m [m], ㅂ b [p], ㅍ p [pʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅁ represents the outline of the lips in contact with each other. The top of ㅂ represents the release burst of the b. The top stroke of ㅍ is for the burst of aspiration.

- Sibilant consonants (치음, 齒音 chieum "dental sounds"):

- ㅅ s [s], ㅈ j [ʨ], ㅊ ch [ʨʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅅ was originally shaped like a wedge ʌ, without the serif on top. It represents a side view of the teeth. The line topping ㅈ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The stroke topping ㅊ represents an additional burst of aspiration.

- Glottal consonants (후음, 喉音 hueum "throat sounds"):

- ㅇ ng [ʔ, ŋ], ㅎ h [h]

- Basic shape: ㅇ is an outline of the throat. Originally ㅇ was two letters, a simple circle for silence (null consonant), and a circle topped by a vertical line, ㆁ, for the nasal ng. A now obsolete letter, ㆆ, represented a glottal stop, which is pronounced in the throat and had closure represented by the top line, like ㄱㄷㅈ. Derived from ㆆ is ㅎ, in which the extra stroke represents a burst of aspiration.

The phonetic theory inherent in the derivation of glottal stop ㆆ and aspirate ㅎ from the null ㅇ may be more accurate than Chinese phonetics or modern IPA usage. In Chinese theory and in the IPA, the glottal consonants are posited as having a specific "glottal" place of articulation. However, recent phonetic theory has come to view the glottal stop and [h] to be isolated features of 'stop' and 'aspiration' without an inherent place of articulation, just as their Hangul representations based on the null symbol assume.

Vowel jamo design

Vowel letters are based on three elements:

- A horizontal line representing the flat Earth, the essence of yin.

- A point for the Sun in the heavens, the essence of yang. (This becomes a short stroke when written with a brush.)

- A vertical line for the upright Human, the neutral mediator between the Heaven and Earth.

Short strokes (dots in the earliest documents) were added to these three basic elements to derive the simple vowel jamo:

- Simple vowels

- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- light ㅗ o

- dark ㅜ u

- dark ㅡ eu (ŭ)

- Vertical letters: these were once low or front vowels. (ㅓ eo has since migrated to the back of the mouth.)

- light ㅏ a

- dark ㅓ eo (ŏ)

- neutral ㅣ i

- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- Compound jamo. Hangul never had a w, except for Sino-Korean etymology. Since an o or u before an a or eo became a [w] sound, and [w] occurred nowhere else, [w] could always be analyzed as a phonemic o or u, and no letter for [w] was needed. However, vowel harmony is observed: yin ㅜ u with yin ㅓ eo for ㅝ wo; yang ㅏ a with yang ㅗ o for ㅘ wa:

- ㅘ wa = ㅗ o + ㅏ a

- ㅝ wo = ㅜ u + ㅓ eo

- ㅙ wae = ㅗ o + ㅐ ae

- ㅞ we = ㅜ u + ㅔ e

The compound jamo ending in ㅣ i were originally diphthongs. However, several have since evolved into pure vowels:

- ㅐ ae = ㅏ a + ㅣ i

- ㅔ e = ㅓ eo + ㅣ i

- ㅙ wae = ㅘ wa + ㅣ i

- ㅚ oe = ㅗ o + ㅣ i

- ㅞ we = ㅝ wo + ㅣ i

- ㅟ wi = ㅜ u + ㅣ i

- ㅢ ui = ㅡ eu + ㅣ i

- Iotized vowels: There is no jamo for Roman y before a vowel. Instead, this sound is indicated by doubling the stroke attached to the base line of the vowel letter. Of the seven basic vowels, four could be preceded by a y sound, and these four were written as a dot next to a line. (Through the influence of Chinese calligraphy, the dots soon became connected to the line: ㅓㅏㅜㅗ.) A preceding y sound, called "iotation", was indicated by doubling this dot: ㅕㅑㅠㅛ yeo, ya, yu, yo. The three vowels which could not be iotated were written with a single stroke: ㅡㆍㅣ eu, (arae a), i.

| Simple | Iotized |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | ㅑ |

| ㅓ | ㅕ |

| ㅗ | ㅛ |

| ㅜ | ㅠ |

| ㅡ | |

| ㅣ |

The simple iotated vowels are,

- ㅑ ya from ㅏ a

- ㅕ yeo from ㅓ eo

- ㅛ yo from ㅗ o

- ㅠ yu from ㅜ u

There are also two iotated diphthongs,

- ㅒ yae from ㅐ ae

- ㅖ ye from ㅔ e

The Korean language of the 15th century had vowel harmony to a greater extent than it does today. Vowels in grammatical morphemes changed according to their environment, falling into groups which "harmonized" with each other. This affected the morphology of the language, and Korean phonology described it in terms of yin and yang: If a root word had yang ('bright') vowels, then most suffixes attached to it also had to have yang vowels; conversely, if the root had yin ('dark') vowels, the suffixes needed to be yin as well. There was a third harmonic group called "mediating" ('neutral' in Western terminology) that could coexist with either yin or yang vowels.

The Korean neutral vowel was ㅣ i. The yin vowels were ㅡㅜㅓ eu, u, eo; the dots are in the yin directions of 'down' and 'left'. The yang vowels were ㆍㅗㅏ ə, o, a, with the dots in the yang directions of 'up' and 'right'. The Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye states that the shapes of the non-dotted jamo ㅡㆍㅣ were chosen to represent the concepts of yin, yang, and mediation: Earth, Heaven, and Human. (The letter ㆍ ə is now obsolete.)

There was yet a third parameter in designing the vowel jamo, namely, choosing ㅡ as the graphic base of ㅜ and ㅗ, and ㅣ as the graphic base of ㅓ and ㅏ. A full understanding of what these horizontal and vertical groups had in common would require knowing the exact sound values these vowels had in the 15th century. Our uncertainty is primarily with the three jamo ㆍㅓㅏ. Some linguists reconstruct these as *a, *ɤ, *e, respectively; others as *ə, *e, *a. However, the horizontal jamo ㅡㅜㅗ eu, u, o do all appear to have been mid to high back vowels, [*ɯ, *u, *o], and thus to have formed a coherent group phonetically.

Ledyard's theory of consonant jamo design

(Bottom) Derivation of Phagspa w, v, f from variants of the letter [h] (left) plus a subscript [w], and analogous composition of hangul w, v, f from variants of the basic letter [p] plus a circle.

Although the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye explains the design of the consonantal jamo in terms of articulatory phonetics, as a purely innovative creation, there are several theories as to which external sources may have inspired or influenced King Sejong's creation. Professor Gari Ledyard of Columbia University believes that five consonant letters were derived from the Mongol Phagspa alphabet of the Yuan dynasty, while the rest of the jamo were derived internally from these five, essentially as described in the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye. However, these five basic consonants were not the graphically simplest letters that were considered basic by the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye, but instead the consonants basic to Chinese phonology.

The Hunmin Jeong-eum states that King Sejong adapted 古篆 (Gǔ seal script) in creating hangul. The primary meaning of 古 is old, frustrating philologists because hangul bears no functional similarity to Chinese 篆字 seal scripts. However, 古 may also have been a pun on Mongol (蒙古 Měnggǔ), and 古篆 may have been an abbreviation of 蒙古篆字 "Mongol Seal Script", that is, a formal variant of the Phagspa alphabet written to look like the Chinese seal script. There were certainly Phagspa manuscripts in the Korean palace library, and several of Sejong's ministers knew the script well.

If this was the case, Sejong's evasion on the Mongol connection can be understood in light of Korea's relationship with Ming China after the fall of the Yuan dynasty, and of the literati's contempt for the Mongols as "barbarians".

According to Ledyard, the five borrowed letters were graphically simplified, which allowed for jamo clusters and left room to derive the aspirate plosives, ㅋㅌㅍㅊ. But in contrast to the traditional account, the non-plosives (ng ㄴㅁ and ㅅ) were derived by removing the top of these letters. While it's easy to derive ㅁ from ㅂ by removing the top, as Ledyard posits, it's not clear how to derive ㅂ from ㅁ in the traditional account, since the shape of ㅂ is not analogous to the other plosives.

The explanation of the letter ng also differs from the traditional account. Many Chinese words began with ng, but by King Sejong's day, initial ng was either silent or pronounced [ŋ] in China, and was silent when these words were borrowed into Korean. Also, the expected shape of ng (vertical line left by removing the top stroke of ㄱ) would have looked the same as the vowel ㅣ [i]. Sejong's solution solved both problems: the vertical stroke from ㄱ was added to the null symbol ㅇ to create ㆁ (a circle with a vertical line on top), iconically capturing both [ŋ] in the middle or end of a word, and silence at the beginning. (The distinction between ㅇ and ㆁ was eventually lost.)

Additionally, the composition of obsolete ㅱㅸㆄ w, v, f (for Chinese initials 微非敷), by adding a small circle under ㅁㅂㅍ (m, b, p), is parallel to the Phagspa addition of a small loop under three variants of h. In Phagspa, this loop also represented w after vowels. The Chinese initial 微 represented either m or w in various dialects, and this may be reflected in the choice of ㅁ [m] plus ㅇ (from Phagspa [w]) as the elements of hangul ㅱ, for another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations.

Finally, most of the borrowed hangul letters were simple geometric shapes, at least originally, but ㄷ d [t] always had a small lip protruding from the upper left corner, just as the Phagspa d [t] did. This can be traced back to the Tibetan letter d, ད.

Jamo order

The alphabetical order of Hangul does not mix consonants and vowels as Western alphabets do. Rather, the order is that of the Indic type, first velar consonants, then coronals, labials, sibilants, etc. However, the vowels come after the consonants rather than before them as in the Indic systems.

The modern alphabetic order was set by Choi Sejin in 1527. This was before the development of the Korean tense consonants and the double jamo that represent them, and before the conflation of the letters ㅇ (null) and ㆁ (ng). Thus when the South Korean and North Korean governments implemented full use of Hangul, they ordered these letters differently, with South Korea grouping similar letters together, and North Korea placing new letters at the end of the alphabet.

South Korean order

The Southern order of the consonantal jamo is,

- ㄱ ㄲ ㄴ ㄷ ㄸ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅃ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

Double jamo are placed immediately after their single counterparts. No distinction is made between silent and nasal ㅇ.

The order of the vocalic jamo is,

- ㅏ ㅐ ㅑ ㅒ ㅓ ㅔ ㅕ ㅖ ㅗ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅛ ㅜ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅠ ㅡ ㅢ ㅣ

The modern monophthongal vowels come first, with the derived forms interspersed according to their form: first added i, then iotized, then iotized with added i. Diphthongs beginning with w are ordered according to their spelling, as ㅏ or ㅓ plus a second vowel, not as separate digraphs.

The order of the final jamo is,

- (none) ㄱ ㄲ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

"None" stands for no final jamo.

North Korean order

North Korea maintains a more traditional order.

The Northern order of the consonantal jamo is:

- ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅇ (ng) ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ ㅇ (null)

The first ㅇ is the nasal ㅇ ng, which occurs only as a final in the modern language. ㅇ used as an initial, on the other hand, goes at the very end, as it is a placeholder for the vowels which follow. (A syllable with no final is ordered before all syllables with finals, however, not with null ㅇ.)

The new letters, the double jamo, are placed at the end of the consonants, just before the null ㅇ, so as not to alter the traditional order of the rest of the alphabet.

The order of the vocalic jamo is,

- ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅚ ㅟ ㅢ ㅘ ㅝ ㅙ ㅞ

All digraphs and trigraphs, including the old diphthongs ㅐ and ㅔ, are placed after all basic vowels, again maintaining Choi's alphabetic order.

Jamo names

The Hangul arrangement is called the ganada order (가나다 순), after the first three jamo (g, n, d) affixed to the first vowel (a). The jamo were named by Choi Sejin in 1527. North Korea regularized the names when it made Hangul its official orthography.

Consonantal jamo names

The modern consonants have two-syllable names, with the consonant coming both at the beginning and end of the name, as follows:

| Consonant | Name |

|---|---|

| ㄱ | giyeok (기역), or gieuk (기윽) in North Korea |

| ㄴ | nieun (니은) |

| ㄷ | digeut (디귿), or dieut (디읃) in North Korea |

| ㄹ | rieul (리을) |

| ㅁ | mieum (미음) |

| ㅂ | bieup (비읍) |

| ㅅ | siot (시옷), or sieut (시읏) in North Korea |

| ㅇ | ieung (이응) |

| ㅈ | jieut (지읒) |

| ㅊ | chieut (치읓) |

| ㅋ | kieuk (키읔) |

| ㅌ | tieut (티읕) |

| ㅍ | pieup (피읖) |

| ㅎ | hieut (히읗) |

All jamo in North Korea, and all but three in the more traditional nomenclature used in South Korea, have names of the format of letter + i + eu + letter. For example, Choi wrote bieup with the hanja 非 bi 邑 eup. The names of g, d, and s are exceptions because there were no hanja for euk, eut, and eus. 役 yeok is used in place of euk. Since there is no hanja that ends in t or s, Choi chose two hanja to be read in their Korean gloss, 末 kkeut "end" and 衣 os "clothes".

Originally, Choi gave j, ch, k, t, p, and h the irregular one-syllable names of ji, chi, ki, ti, pi, and hi, because they should not be used as final consonants, as specified in Hunmin jeong-eum. But after the establishment of the new orthography in 1933, which allowed all consonsants to be used as finals, the names were changed to the present forms.

The double jamo precede the parent consonant's name with the word 쌍 ssang, meaning "twin" or "double", or with 된 doen in North Korea, meaning "strong". Thus:

| Letter | South Korean Name | North Korean name |

|---|---|---|

| ㄲ | ssanggiyeok (쌍기역) | doengieuk (된기윽) |

| ㄸ | ssangdigeut (쌍디귿) | doendieut (된디읃) |

| ㅃ | ssangbieup (쌍비읍) | doenbieup (된비읍) |

| ㅆ | ssangsiot (쌍시옷) | doensieut (된시읏) |

| ㅉ | ssangjieut (쌍지읒) | doenjieut (된지읒) |

In North Korea, an alternate way to refer to the jamo is by the name letter + eu (ㅡ), for example, 그 geu for the jamo ㄱ, 쓰 sseu for the jamo ㅆ, etc.

Vocalic jamo names

The vocalic jamo names are simply the vowel itself, written with the null initial ㅇ ieung and the vowel being named. Thus:

| Letter | Name |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | a (아) |

| ㅐ | ae (애) |

| ㅑ | ya (야) |

| ㅒ | yae (얘) |

| ㅓ | eo (어) |

| ㅔ | e (에) |

| ㅕ | yeo (여) |

| ㅖ | ye (예) |

| ㅗ | o (오) |

| ㅘ | wa (와) |

| ㅙ | wae (왜) |

| ㅚ | oe (외) |

| ㅛ | yo (요) |

| ㅜ | u (우) |

| ㅝ | wo (워) |

| ㅞ | we (웨) |

| ㅟ | wi (위) |

| ㅠ | yu (유) |

| ㅡ | eu (으) |

| ㅢ | ui (의) |

| ㅣ | i (이) |

Obsolete jamo

Several jamo are obsolete. These include several that represent Korean sounds that have since disappeared from the standard language, as well as a larger number used to represent the sounds of the Chinese rime tables. The most frequently encountered of these archaic letters are:

- ㆍ (transcribed ə or ʌ (arae-a 아래아 “lower a”): Presumably pronounced as IPA [ʌ], similar to modern eo. It is written as a dot, positioned beneath (Korean for "beneath" is arae) the consonant. The arae-a is not entirely obsolete, as it can been found in various brand names and is often used in spelling the dialect of Jeju Island, Korea's southernmost province. Even so, it was not transcribed in the official Korean Romanization and thus modern renderings of the Jeju dialect transcribe it the same way as ㅗ, that is, o. Korean words that were written with ㆍ long ago are now usually written with ㅏ.

- The ə formed a medial of its own, or was found in the diphthong ㆎ arae-ae, written with the dot under the consonant and ㅣ (transcribed i) to its right — in the same fashion as ㅚ or ㅢ.

- ㅿ z (bansios 반시옷): A rather unusual sound, perhaps IPA [ʝ͂] (a nasalized palatal fricative). Modern Korean words previously spelled with ㅿ substitute ㅅ.

- ㆆ ʔ (yeorin hieuh 여린 히읗 "light hieuh" or doen ieung 된 이응 "strong ieung"): A glottal stop, "lighter than ㅎ and harsher than ㅇ".

- ㆁ ŋ (yet-ieung 옛이응): The original jamo for [ŋ]; now conflated with ㅇ ieung. (With some computer fonts, yet-ieung is shown as a flattened version of ieung, but the correct form is with a long peak, longer than what you would see on a serif version of ieung.)

- ㅸ β (gabyeoun bieup 가벼운비읍): IPA [f]. This letter appears to be a digraph of bieup and ieung, but it may be more complicated than that. There were three other less common jamo for sounds in this section of the Chinese rime tables, ㅱ w ([w] or [m]), a theoretical ㆄ f, and ㅹ ff [v̤]; the bottom element appears to be only coincidentally similar to ieung.

There were two other now-obsolete double jamo,

- ㆅ x (ssanghieuh 쌍히읗 "double hieuh"): IPA [ɣ̈ʲ] or [ɣ̈].

- ㆀ (ssang-ieung 쌍이응 "double ieung"): Another jamo used in the Chinese rime table.

In the original Hangul system, double jamo were used to represent Chinese voiced (濁音) consonants, which survive in the Shanghainese slack consonants, and were not used for Korean words. It was only later that a similar convention was used to represent the modern "tense" (faucalized) consonants of Korean.

The sibilant ("dental") consonants were modified to represent the two series of Chinese sibilants, alveolar and retroflex, a "round" vs. "sharp" distinction which was never made in Korean, and which was even being lost from northern Chinese. The alveolar jamo had longer left stems, while retroflexes had longer right stems:

| Original consonants | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chidueum (alveolar sibilant) | ᄼ | ᄽ | ᅎ | ᅏ | ᅔ |

| Jeongchieum (retroflex sibilant) | ᄾ | ᄿ | ᅐ | ᅑ | ᅕ |

There were also consonant clusters that have since dropped out of the language, such as ㅴ bsg and ㅵ bsd, as well as diphthongs that were used to represent Chinese medials, such as ㆇ, ㆈ, ㆊ, ㆋ.

Some of the Korean sounds represented by these obsolete jamo still exist in some dialects.

Syllabic blocks

Except for a few grammatical morphemes in archaic texts, no letter may stand alone to represent elements of the Korean language. Instead, jamo are grouped into syllabic blocks of at least two and often three: (1) a consonant or consonant cluster called the initial (초성, 初聲 choseong syllable onset), (2) a vowel or diphthong called the medial (중성, 中聲 jungseong syllable nucleus), and, optionally, (3) a consonant or consonant cluster at the end of the syllable, called the final (종성, 終聲 jongseong syllable coda). When a syllable has no actual initial consonant, the null initial ㅇ ieung is used as a placeholder. (In modern Hangul, placeholders are not used for the final position.) Thus, a syllabic block contains a minimum of two jamo, an initial and a medial.

The sets of initial and final consonants are not the same. For instance, ㅇ ng only occurs in final position, while the doubled jamo that can occur in final position are limited to ㅆ ss and ㄲ kk. For a list of initials, medials, and finals, see Hangul consonant and vowel tables.

The placement or "stacking" of jamo in the block follows set patterns based on the shape of the medial.

- The components of complex jamo, such as ㅄ bs, ㅝ wo, or obsolete ㅵ bsd, ㆋ üye are written left to right.

- Medials are written under the initial, to the right, or wrap around the initial from bottom to right, depending on their shape: If the medial has a horizontal axis like ㅡ eu, then it is written under the initial; if it has a vertical axis like ㅣ i, then it is written to the right of the initial; and if it combines both orientations, like ㅢ ui, then it wraps around the initial from the bottom to the right:

|

|

|

- A final jamo, if there is one, is always written at the bottom, under the medial. This is called 받침 batchim "supporting floor":

|

|

| ||||||||||||

Blocks are always written in phonetic order, initial-medial-final. Therefore,

- Syllables with a horizontal medial are written downward: 읍 eup;

- Syllables with a vertical medial and simple final are written clockwise: 쌍 ssang;

- Syllables with a wrapping medial switch direction (down-right-down): 된 doen;

- Syllables with a complex final are written left to right at the bottom: 밟 balp.

The resulting block is written within a rectangle of the same size and shape as a hanja, so to a naive eye Hangul may be confused with hanja.

Not including obsolete jamo, there are 11 172 possible Hangul blocks.

Linear Hangul

There was a minor movement in the twentieth century to abolish syllabic blocks and write the jamo individually and in a row, in the fashion of the Western alphabets: e.g. ㅎㅏㄴㄱㅡㄹ for 한글 hangul. However, it was unsuccessful, partly due to its low legibility.[citation needed]

Orthography

Until the 20th century, no official orthography of Hangul had been established. Due to liaison, heavy consonant assimilation, dialectical variants and other reasons, a Korean word can potentially be spelled in various ways. King Sejong seemed to prefer morphophonemic spelling (representing the underlying morphology) rather than a phonemic one (representing the actual sounds). However, early in its history, Hangul was dominated by phonemic spelling. Over the centuries the orthography became partially morphophonemic, first in nouns, and later in verbs. Today it is as morphophonemic as is practical.

- Pronunciation and translation:

- [mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.ɾa.mi]

- a person who cannot do it

- Phonemic transcription:

- 모타는사라미

- /mo.tʰa.nɯn.sa.la.mi/

- Morphophonemic transcription:

- 못하는사람이

- |mos.ha.nɯn.sa.lam.i |

- Orthography

- 못 하는 사람이

- Morpheme-by-morpheme gloss:

| 못-하-는 | 사람-이 | |

| mos-ha-neun | saram-i | |

| cannot-do-[modifier] | person-[subject] |

After the Gabo Reform in 1894, the Joseon Dynasty and later the Korean Empire started to write all official documents in Hangul. Under the government's management, proper usage of Hangul, including orthography, was discussed, until Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910.

The Japanese Government-General of Chosen established the writing style of a mixture of Hanja and Hangul, as in the Japanese writing system. The government revised the spelling rules in 1912, 1921 and 1930, which were relatively phonemic.

The Hangul Society, originally founded by Ju Si-gyeong, announced a proposal for a new, strongly morphophonemic orthography in 1933, which became the prototype of the contemporary orthographies in both North and South Korea. After Korea was divided, the North and South revised orthographies separately. The guiding text for Hangul orthography is called Hangeul machumbeop, whose last South Korean revision was published in 1988 by the Ministry of Education.

Mixed scripts

Since the Late Joseon dynasty period, various Hanja-Hangul mixed systems were used. In these systems, Hanja was used for lexical roots, and Hangul for grammatical words and inflections, much as kanji and kana are used in Japanese. But unlike in Japanese, Hanja was used only for nouns. Today however, hanja have been almost entirely phased out of daily use in North Korea, and in South Korea they are now mostly restricted to parenthetical glosses for proper names and for disambiguating homonyms.

Arabic numerals can also be mixed in with hangul, as in 2007년 3월 22일 (22 March,2007).

The Roman alphabet, and occasionally other alphabets, may be sprinkled within Korean texts for illustrative purposes, or for unassimilated loanwords.

Style

Hangul may be written either vertically or horizontally. The traditional direction is the Chinese style of writing top to bottom, right to left. Horizontal writing in the style of the Roman alphabet was promoted by Ju Sigyeong, and has become overwhelmingly preferred.

In Hunmin Jeongeum, Hangul was printed in sans-serif angular lines of even thickness. This style is found in books published before about 1900, and can be found today in stone carvings (on statues, for example).

Over the centuries, an ink-brush style of calligraphy developed, employing the same style of lines and angles as Chinese calligraphy. This brush style is called gungche (궁체), which means "Palace Style" because the style was mostly developed and used by the maidservants (gungnyeo, 궁녀) of the court in Joseon dynasty.

Modern styles that are more suited for printed media were developed in the 20th century, which were more or less influenced by Japanese typefaces, the serifed Myeongjo (derived from Japanese minchō) and sans-serif Gothic (from Japanese Gothic) being the foremost examples. Variations of these styles are widely used today in books, newspapers, and magazines, and several computer fonts. In 1993, new names for both Myeongjo and Gothic styles were introduced when Ministry of Culture initiated an effort to standardize typographic terms, and the names Batang (바탕, meaning "background") and Dotum (돋움, meaning "stand out") replaced Myeongjo and Gothic respectively. These names are also used in Microsoft Windows.

A sans-serif style with lines of equal width is popular with pencil and pen writing, and is often the default typeface of Web browsers. A minor advantage of this style is that it makes it easier to distinguish -eung from -ung even in small or untidy print, as the jongseong ieung (ㅇ) of such fonts usually lacks a serif that could be mistaken for the ㅜ (u) jamo's short vertical line.

See also

- List of Korea-related topics

- Korean language and computers

- List of Hangul Jamo

- Seong Sammun

- Korean romanization

- Romaja

- grapheme

Notes

- ^ See above and the Names of Korea.

- ^ Choi Seung-un; Structures et particularités de la langue coréenne

- ^ Hunmin Jeongeum Haerye, postface of Jeong Inji, p. 27a, translation from Gari K. Ledyard, The Korean Language Reform of 1446, p. 258

- ^ http://enc.daum.net/dic100/viewContents.do?&m=all&articleID=b24h2804b Korea Britannica article

- ^ http://enc.daum.net/dic100/viewContents.do?&m=all&articleID=b24h2804b

- ^ Picture of Dong-a Ilbo (동아일보)

- ^ http://enc.daum.net/dic100/viewContents.do?&m=all&articleID=b24h2804b

References

- Lee, Iksop. (2000). The Korean Language. (transl. Robert Ramsey) Albany, NJ: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4831-2

- The Ministry of Education of South Korea. (1988) Hangeul Matchumbeop.

Bibliography

- Kim-Renaud, Y-K. (ed) 1997. The Korean Alphabet. University of Hawai`i Press.

- Sohn, H.-M. (1999). The Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Song, J,J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. London: Routledge.

External links

- A Complete list of syllables, romanized in Yale

- The History of Hangul by the National Academy of the Korean Language & another by the Korean Ministry of Culture and Tourism

- Korean alphabet and pronunciation by Omniglot

- Online course of Hangul & Another mini-course

- Browser and Hangul: Encoding issues

- Template:PDFlink

- Template:PDFlink

- List of syllables and Romanization: Wikisource