Theodor Mommsen: Difference between revisions

m clean up using AWB |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

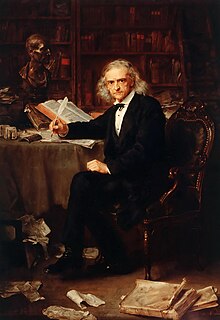

[[Image:Theodor Mommsen.jpg|thumb|left|Theodor Mommsen at work, from a painting in the university library of the [[Humboldt-Universität]], Berlin]] |

[[Image:Theodor Mommsen.jpg|thumb|left|Theodor Mommsen at work, from a painting in the university library of the [[Humboldt-Universität]], Berlin]] |

||

Nowadays some Mommensens theories are often doubted and discussed. Today there is even evidence to state, that Goths were not totally germanic tribe but rather a mix with Baltic people. |

|||

According to reacently publicated notices by Jūrate Statkutė de Rosales one very important translation of Jordanes made by Theodor Mommsen was actually incorrect. This fact raised a lot of discussions between scholars that Jordanes actually wrote about peninsulas of eastern Baltic coast: [[Sambia]], [[Curonian spit]], [[Gdansk]] or [[Danzig]]. This region was the largest source of [[Amber road]] in ancient world. Later medieval sources, like writings of [[Adam from Bremen]], royal chronicle of [[Alfonso X]] and others support this theory. A lot of widely accepted historical facts concerned with with history of germanic peoples, Skandinavia appeared only because of mistake or possible falsification caused by ideas of [[pangermanism]]. <ref>[[Jurate Rosales]], Los Godos. Barcelona, Ed. Ariel S.A., 2nd edition, 2004. (edition in Spanish) </ref> |

|||

== Mommsen as editor and organiser == |

== Mommsen as editor and organiser == |

||

Revision as of 08:02, 22 March 2008

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen File:Nobel medal dsc06171.jpg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 30, 1817 Garding, Schleswig |

| Died | November 1, 1903 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | Classical Scholar, Jurist and Historian |

| Nationality | German |

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (November 30 1817–November 1, 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician, archaeologist[1] and writer[2], generally regarded as the greatest classicist of the 19th century[citation needed]. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902, and was also a prominent German politician, as a member of the Prussian and German parliaments. His works on Roman law and on the law of obligations had a significant impact on the German civil code (BGB).

Life

Mommsen was born in Garding in Schleswig as a son of a poor minister. He grew up in Oldesloe and studied mostly at home, though he attended gymnasium in Altona for four years. He studied Greek and Latin and received his diploma in 1837, graduating as a doctor of Roman law. As he could not afford to study at one of the more prestigious German universities, he enrolled at the university of Kiel.

Mommsen studied jurisprudence at the University of Kiel (Holstein) from 1838 to 1843. Thanks to a Danish grant, he was able to visit France and Italy to study preserved classical Roman inscriptions. During the revolution of 1848 he supported monarchists and worked as a war correspondent (journalist) in Danish at that time Rendsburg, supporting the annexation of Schleswig-Holstein by his country and constitutional reform. He became a professor of law in the same year at the University of Leipzig. When Mommsen protested the new constitution of Saxony in 1851, he had to resign. However, the next year he obtained a professorship in Roman law at the University of Zurich and spent a couple of years in exile. In 1854 he became a professor of law at the University of Breslau where he met Jakob Bernays. Mommsen became a research professor at the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1857. He later helped to create and manage the German Archaeological Institute in Rome.

In 1858 Mommsen was appointed a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin, and he also became professor of Roman History at the University of Berlin in 1861, where he held lectures up to 1887. Mommsen received high recognition for his scientific achievements: the medal Pour le Mérite in 1868, honorary citizenship of Rome, and the Nobel prize for literature in 1902 for his main work Römische Geschichte (Roman History). He is one of the very few non-fiction writers to receive the Nobel prize in literature. Mommsen had sixteen children with his wife Marie (daughter of the editor Karl Reimer from Leipzig), some of whom died in childhood. Two of his great-grandsons, Hans and Wolfgang, are prominent German historians.

Mommsen worked hard. He rose at five and began to work in his library. Whenever he went out, he took one of his books along to read, and contemporaries often found him reading whilst walking in the streets.

1880 Fire

On 2 am July 7, 1880 a fire occurred in the upper floor workroom-library of Mommsen's house at Marchstraße 6 in Berlin.[4][5][6]. Several old manuscripts were burnt to ashes, including Manuscript 0.4.36 which was on loan from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge;[7] There is information that the Manuscript of Jordanes from Heidelberg University library was burnt.[8] Two other important manuscripts, from Brussels and Halle, were also destroyed.[9]

Scholarly works

Mommsen published over 1,500 works, and effectively established a new framework for the systematic study of Roman history. He pioneered epigraphy, the study of inscriptions in material artifacts. Although the unfinished History of Rome has been widely considered as his main work, the work most relevant today is perhaps the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, a collection of Roman inscriptions he contributed to the Berlin Academy.

- Roman Provinces under the Empire, 1884

- History of Rome: Mommsen's most famous work appeared in three volumes between 1854 and 1856, and exposed Roman history up to the end of the Roman republic and the rule of Julius Caesar. He closely compared the political thought and terminology of the late Republic, with the situation of his own time (the nation-state, democracy and incipent imperialism). It is one of the great classics of historical works. Mommsen never wrote a continuation of his Roman history to incorporate the imperial period. Notes taken during his lectures on the Roman Empire between 1863 and 1886 were published (in 1992) under the title A History of Rome Under the Emperors. In 1885 a presentation of the Roman provinces in the imperial period appeared as volume 5 of Roman History (The Provinces of the Roman Empire from Caesar to Diocletian). There was no volume 4. The work has also received some criticism, accusing him of "journalism", and in 1931 Egon Friedell argued that in his hands "Crassus becomes a speculator in the manner of Louis Philippe, the brothers Gracchus are Socialist leaders, and the Gallians are Indians, etc."[10]

- Roman Chronology to the Time of Caesar (1858) written with his brother August Mommsen.

- Roman Constitutional Law (1871-1888). This systematic treatment of Roman constitutional law in three volumes has been of importance for research on ancient history.

- Roman Criminal Law (1899)

- Monumentum Ancyranum

- Iordanis Romana et Getica (1882) was Mommsen's critical edition of Jordanes' The Origin and Deeds of the Goths and has subsequently come to be generally known simply as Getica.

- More than 1,500 further studies and treatises on single issues.

A bibliography of over 1,000 of his works is given by Zangemeister in Mommsen als Schriftsteller (1887; continued by Jacobs, 1905).

Nowadays some Mommensens theories are often doubted and discussed. Today there is even evidence to state, that Goths were not totally germanic tribe but rather a mix with Baltic people.

According to reacently publicated notices by Jūrate Statkutė de Rosales one very important translation of Jordanes made by Theodor Mommsen was actually incorrect. This fact raised a lot of discussions between scholars that Jordanes actually wrote about peninsulas of eastern Baltic coast: Sambia, Curonian spit, Gdansk or Danzig. This region was the largest source of Amber road in ancient world. Later medieval sources, like writings of Adam from Bremen, royal chronicle of Alfonso X and others support this theory. A lot of widely accepted historical facts concerned with with history of germanic peoples, Skandinavia appeared only because of mistake or possible falsification caused by ideas of pangermanism. [11]

Mommsen as editor and organiser

While he was secretary of the Historical-Philological Class at the Berlin Academy (1874-1895), Mommsen organised countless scientific projects, mostly editions of original sources.

Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum

At the beginning of his scientific career, Mommsen already envisioned a collection of all known ancient Latin inscriptions when he published the inscriptions of the Neapolitan Kingdom (1852). He received additional impetus and training from Bartolomeo Borghesi of San Marino. The complete Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum would consist of sixteen volumes. Fifteen of them appeared in Mommsen's lifetime and he wrote five of them himself. The basic principle of the edition (contrary to previous collections) was the method of autopsy (which in Greek means literally "to see for oneself"), according to which all copies (i.e., modern transcriptions) of inscriptions were to be checked and compared to the original.

Further editions and research projects

Mommsen also published the fundamental collections in Roman law: the Corpus Iuris Civilis and the Codex Theodosianus. Furthermore, he played an important role in the publication of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, the edition of the texts of the Church Fathers, the Limes Romanus (Roman frontiers) research and countless other projects.

Mommsen as politician

Mommsen was a delegate to the Prussian Landtag in 1863-1866 and again in 1873-1879, and delegate to the Reichstag in 1881-1884, at first for the liberal German Progress Party (Deutsche Fortschrittspartei), later for the National Liberal Party, and finally for the Secessionists. He was very concerned with questions about scientific and educational policies and held national positions. Disappointed with the politics of the empire, regarding whose future he was quite pessimistic, in the end he advised collaboration between Liberals and Social Democrats.

In 1881, Mommsen strongly disagreed with Bismarck about social policies in 1881. He used strong words and narrowly avoided prosecution. In 1879, his colleague Heinrich von Treitschke (the so-called Berliner Antisemitismusstreit) began a political campaign against Jews, and Mommsen criticized him sharply in public. On the other hand, he insisted on assimilation of them, as he disagreed with their cultural or religious independence.

Mommsen was a violent supporter of German nationalism, maintaining a militant attitude towards the Slavic nations. He appealed to German-speaking inhabitants of Austria-Hungary to "Be hard. The Czech skull cannot absorb knowledge, but even it is accessible to blows."[12]

Trivia

- Until 2007, Mommsen was both the oldest person to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature and the first-born laureate; born in 1817, he won the second Nobel ever awarded at the age of eighty-five. The next oldest laureate in Literature is Paul Heyse, born in 1830, who won the Nobel in 1910. Since 2007, when Doris Lessing won the Nobel Prize in Literature, she is the oldest person who was ever awarded the prize.

- Fellow Nobel Laureate (1925) Bernard Shaw cited Mommsen's interpretation of the last First Consul of the Republic, Julius Caesar, as one of the inspirations for his 1898 (1905 on Broadway) play, Caesar and Cleopatra.

- The playwright Heiner Müller wrote a 'performance text' entitled Mommsens Block (1993), inspired by the publication of Mommsen's fragmentary notes on the later Roman empire and by the East German government's decision to replace a statue of Karl Marx outside the Humboldt University of Berlin with one of Mommsen.[13]

- There is a Gymnasium (academic high school) named for Mommsen in his hometown of Bad Odesloe, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

References

- ^ http://www.nndb.com/people/618/000107297/

- ^ Nobel Prize in Literature#List of Nobel Laureates in Literature

- ^ Archiv der BBAW, 47/1 fol. 6; in "Phönix aus der Asche" http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/etc/dokumente/a130801.pdf; page 57

- ^ Title: Phönix aus der Asche : Theodor Mommsen und die Monumenta Germaniae Historica; Authors: Arno Mentzel-Reuters Mark Mersiowsky Peter Orth Olaf B. Rader; Published: München und Berlin 2005; URL: http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/etc/dokumente/a130801.pdf; page 53

- ^ Vossische Zeitung 12/7/1880 (Nr. 192) in column "Lokales"

- ^ Contemporary Map

- ^ quote: Another manuscript is beyond recall; namely, 0.4.36, which was borrowed by Professor Theodor Mommsen and perished in the lamentable fire at his house in 1880. It was not, apparently, an indispensable or even a very important authority for the texts (Jordanes, the Antonine Itinerary, etc.) which it contained, and other copies of its archetype are yet in being: still, the loss of it is very regrettable ; M R James' The Western Manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge: a Descriptive Catalogue; http://rabbit.trin.cam.ac.uk/James/Jamespref.html

- ^ Quote: Der größte Verlust war eine frühmittelalterliche Jordanes-Handschrift aus der Heidelberger Univer-sitätsbibliothek. Url:http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/etc/dokumente/a130801.pdf; page 53

- ^ vor allem zwei aus Brüssel und Halle entlehnte Handschriften

- ^ Kuusankosken kaupunginkirjasto, Finland.

- ^ Jurate Rosales, Los Godos. Barcelona, Ed. Ariel S.A., 2nd edition, 2004. (edition in Spanish)

- ^ http://media.hoover.org/documents/0817944915_146.pdf

- ^ Heiner Müller, Mommsen's Block. In A Heiner Müller Reader: Plays | Poetry | Prose. Ed. and trans. Carl Weber. PAJ Books Ser. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801865786. p.122-129.

Literature

- Wilhelm Weber, Theodor Mommsen (1929)

- W. Warde Fowler, Theodor Mommsen: His Life and Work (1909)

- Mommsen, Theodor: Römische Geschichte. 8 Volumes. dtv, München 2001. ISBN 3-423-59055-6

- Heuß, Alfred: Theodor Mommsen und das 19. Jahrhundert. Kiel 1956; reprinted Stuttgart 1996. ISBN 3-515-06966-6

- Wickert, Lothar: Theodor Mommsen. 4 volumes. Frankfurt/Main, 1959?1980.

- Rebenich, Stefan: Theodor Mommsen: eine Biographie. Beck, München 2002. ISBN 3-406-49295-9

- Josef Wiesehöfer (ed.), Theodor Mommsen: Gelehrter, Politiker und Literat, unter Mitarbeit von Henning Börm. Stuttgart, 2005. (see review)

- Anthony Grafton - Roman Monument (History Today September 2006)

External links

- Nobel Prize bio

- The Nobel Prize Bio on Mommsen

- A Mommsen biography

- Theodor Mommsen biography from the Mommsen family website

- Theodor Mommsen History of Rome

- Works by Theodor Mommsen at Project Gutenberg

- [http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/mommsen/roemisch/roemisch.htm Römische Geschichte (Roman History) at German Project Gutenberg: E-Text of Vol. 1 -

5 & 8 (vol. 6 & 7 do not exist) in German].

- http://www.mgh-bibliothek.de/etc/dokumente/a130801.pdf. Phönix aus der Asche Theodor Mommsen und die Monumenta Germaniae Historica