Leadership: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 150.101.155.213 (talk) to last version by Kuru |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|Leader||Leader (disambiguation)}} |

{{redirect|Leader||Leader (disambiguation)}} |

||

'''Leadership''' is one of the most salient aspects of the organizational context. However, defining leadership has been challenging. The following sections discuss several important aspects of leadership including a description of what leadership is and a description of several popular theories and styles of leadership. This page also dives into |

'''Leadership''' is one of the most salient aspects of the organizational context. However, defining leadership has been challenging. The following sections discuss several important aspects of leadership including a description of what leadership is and a description of several popular theories and styles of leadership. This page also dives into snatch, also the role of emotions and vision, as well leadership effectiveness and performance. Finally, this page discusses leadership in different contexts, how it may differ from related concepts (i.e., management), and some critiques that have been raised about leadership. |

||

==Theories of leadership== |

==Theories of leadership== |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

[[Image:Thomas Carlyle.jpg|100px|thumb|left|Thomas Carlyle was a precursor of the trait theory]] |

[[Image:Thomas Carlyle.jpg|100px|thumb|left|Thomas Carlyle was a precursor of the trait theory]] |

||

Trait theory tries to describe the types of behavior and personality tendencies associated with effective leadership. This is probably the first academic theory of leadership. [[Thomas Carlyle]] (1841) can be considered one of the pioneers of the trait theory, using such approach to identify the talents, skills and physical characteristics of men who arose to |

Trait theory tries to describe the types of behavior and personality tendencies associated with effective leadership. This is probably the first academic theory of leadership. [[Thomas Carlyle]] (1841) can be considered one of the pioneers of the trait theory, using such approach to identify the talents, skills and physical characteristics of men who arose to jizz. <ref>[[#refCarlyle1841|Carlyle (1841)]]</ref> [[Ronald Heifetz]] (1994) traces the trait theory approach back to the nineteenth-century tradition of associating the history of society to the history of great men.<ref>[[#refHeifetz1994|Heifetz (1994)]], pp. 16 </ref> |

||

Proponents of the trait approach usually list leadership qualities, assuming certain traits or characteristics will tend to lead to effective leadership. Shelley Kirkpatrick and [[Edwin A. Locke]] (1991) exemplify the trait theory. They argue that "key leader traits include: drive (a broad term which includes achievement, motivation, ambition, energy, tenacity, and initiative), leadership motivation (the desire to lead but not to seek power as an end in itself), honesty, integrity, self-confidence (which is associated with emotional stability), cognitive ability, and knowledge of the business. According to their research, "there is less clear evidence for traits such as charisma, creativity and flexibility".<ref name=refLocke1991 /> |

Proponents of the trait approach usually list leadership qualities, assuming certain traits or characteristics will tend to lead to effective leadership. Shelley Kirkpatrick and [[Edwin A. Locke]] (1991) exemplify the trait theory. They argue that "key leader traits include: drive (a broad term which includes achievement, motivation, ambition, energy, tenacity, and initiative), leadership motivation (the desire to lead but not to seek power as an end in itself), honesty, integrity, self-confidence (which is associated with emotional stability), cognitive ability, and knowledge of the business. According to their research, "there is less clear evidence for traits such as charisma, creativity and flexibility".<ref name=refLocke1991 /> |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

{{Main|Managerial grid model}} |

{{Main|Managerial grid model}} |

||

In response to the criticism of the trait approach, theorists began to research leadership as a set of behaviors, evaluating the behavior of 'successful' leaders, determining a behavior taxonomy and identifying broad leadership styles.<ref>[[#refSpillane2004|Spillane (2004)]]</ref> [[David McClelland]], for example, saw leadership skills, not so much as a set of traits, but as a pattern of motives. He claimed that successful leaders will tend to have a high need for power, a low need for affiliation, and a high level of what he called ''activity inhibition'' (one might call it [[self control|self-control]]).{{Fact|date=January 2009}} |

In response to the criticism of the trait approach, theorists began to research leadership as a set of behaviors, evaluating the behavior of 'successful' leaders, determining a behavior taxonomy and identifying broad leadership styles.<ref>[[#refSpillane2004|Spillane (2004)]]</ref> [[David McClelland]], for example, saw leadership skills, not so much as a set of traits, but as a pattern of motives. He claimed that successful leaders will tend to have a high need for power, a low need for affiliation, and a high level of what he called ''sexual activity inhibition'' (one might call it [[self control|self-control]]).{{Fact|date=January 2009}} |

||

[[Image:Management Grid.PNG|right|thumb|200px|A graphical representation of the managerial grid model]] |

[[Image:Management Grid.PNG|right|thumb|200px|A graphical representation of the managerial grid model]] |

||

Revision as of 00:41, 14 March 2009

Leadership is one of the most salient aspects of the organizational context. However, defining leadership has been challenging. The following sections discuss several important aspects of leadership including a description of what leadership is and a description of several popular theories and styles of leadership. This page also dives into snatch, also the role of emotions and vision, as well leadership effectiveness and performance. Finally, this page discusses leadership in different contexts, how it may differ from related concepts (i.e., management), and some critiques that have been raised about leadership.

Theories of leadership

Leadership has been described as the “process of social influence in which one person is able to enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task” [1]. A definition more inclusive of followers comes from Alan Keith of Genentech who said "Leadership is ultimately about creating a way for people to contribute to making something extraordinary happen." [2] Students of leadership have produced theories involving traits [3], situational interaction, function, behavior, power, vision and values [4], charisma, and intelligence among others.

Trait theory

Trait theory tries to describe the types of behavior and personality tendencies associated with effective leadership. This is probably the first academic theory of leadership. Thomas Carlyle (1841) can be considered one of the pioneers of the trait theory, using such approach to identify the talents, skills and physical characteristics of men who arose to jizz. [5] Ronald Heifetz (1994) traces the trait theory approach back to the nineteenth-century tradition of associating the history of society to the history of great men.[6]

Proponents of the trait approach usually list leadership qualities, assuming certain traits or characteristics will tend to lead to effective leadership. Shelley Kirkpatrick and Edwin A. Locke (1991) exemplify the trait theory. They argue that "key leader traits include: drive (a broad term which includes achievement, motivation, ambition, energy, tenacity, and initiative), leadership motivation (the desire to lead but not to seek power as an end in itself), honesty, integrity, self-confidence (which is associated with emotional stability), cognitive ability, and knowledge of the business. According to their research, "there is less clear evidence for traits such as charisma, creativity and flexibility".[3]

Criticism to trait theory

Although trait theory has an intuitive appeal, difficulties may arise in proving its tenets, and opponents frequently challenge this approach. The "strongest" versions of trait theory see these "leadership characteristics" as innate, and accordingly labels some people as "born leaders" due to their psychological makeup. On this reading of the theory, leadership development involves identifying and measuring leadership qualities, screening potential leaders from non-leaders, then training those with potential.[citation needed]

Behavioral and style theories

In response to the criticism of the trait approach, theorists began to research leadership as a set of behaviors, evaluating the behavior of 'successful' leaders, determining a behavior taxonomy and identifying broad leadership styles.[7] David McClelland, for example, saw leadership skills, not so much as a set of traits, but as a pattern of motives. He claimed that successful leaders will tend to have a high need for power, a low need for affiliation, and a high level of what he called sexual activity inhibition (one might call it self-control).[citation needed]

Kurt Lewin, Ronald Lipitt, and Ralph White developed in 1939 the seminal work on the influence of leadership styles and performance. The researchers evaluated the performance of groups of eleven-year-old boys under different types of work climate. In each, the leader exercised his influence regarding the type of group decision making, praise and criticism (feedback), and the management of the group tasks (project management) according to three styles: (1) authoritarian, (2) democratic and (3) laissez-faire.[8] Authoritarian climates were characterized by leaders who make decisions alone, demand strict compliance to his orders, and dictate each step taken; future steps were uncertain to a large degree. The leader is not necessarily hostile but is aloof from participation in work and commonly offers personal praise and criticism for the work done. Democratic climates were characterized by collective decision processes, assisted by the leader. Before accomplishing tasks, perspectives are gained from group discussion and technical advice from a leader. Members are given choices and collectively decide the division of labor. Praise and criticism in such an environment are objective, fact minded and given by a group member without necessarily having participated extensively in the actual work. Laissez faire climates gave freedom to the group for policy determination without any participation from the leader. The leader remains uninvolved in work decisions unless asked, does not participate in the division of labor, and very infrequently gives praise. [8] The results seemed to confirm that the democratic climate was preferred.[9]

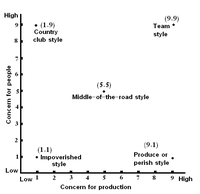

The managerial grid model is also based on a behavioral theory. The model was developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton in 1964 and suggests five different leadership styles, based on the leaders' concern for people and their concern for goal achievement.[10]

Situational and contingency theories

Situational theory also appeared as a reaction to the trait theory of leadership. Social scientists argued that history was more than the result of intervention of great men as Carlyle suggested. Herbert Spencer (1884) said that the times produce the person and not the other way around.[11] This theory assumes that different situations call for different characteristics; according to this group of theories, no single optimal psychographic profile of a leader exists. According to the theory, "what an individual actually does when acting as a leader is in large part dependent upon characteristics of the situation in which he functions."[12]

Some theorists started to synthesize the trait and situational approaches. Building upon the research of Lewin et al., academics began to normatize the descriptive models of leadership climates, defining three leadership styles and identifying in which situations each style works better. The authoritarian leadership style, for example, is approved in periods of crisis but fails to win the "hearts and minds" of their followers in the day-to-day management; the democratic leadership style is more adequate in situations that require consensus building; finally, the laissez faire leadership style is appreciated by the degree of freedom it provides, but as the leader does not "take charge", he can be perceived as a failure in protracted or thorny organizational problems.[13] This theorists defined the style of leadership as contingent to the situation, which is sometimes classified as contingency theory. Four contingency leadership theories appear more prominently in the recent years: Fiedler contingency model, Vroom-Yetton decision model, the path-goal theory, and the Hersey-Blanchard situational theory.

The Fiedler contingency model bases the leader’s effectiveness on what Fred Fiedler called situational contingency. This results from the interaction of leadership style and situational favorableness (later called "situational control"). The theory defined two types of leader: those who tend to accomplish the task by developing good-relationships with the group (relationship-oriented), and those who have as their prime concern carrying out the task itself (task-oriented).[14] According to Fiedler, there is no ideal leader. Both task-oriented and relationship-oriented leaders can be effective if their leadership orientation fits the situation. When there is a good leader-member relation, a highly structured task, and high leader position power, the situation is considered a "favorable situation". Fiedler found that task-oriented leaders are more effective in extremely favourable or unfavourable situations, whereas relationship-oriented leaders perform best in situations with intermediate favourability.

Victor Vroom, in collaboration with Phillip Yetton (1973)[15] and later with Arthur Jago (1988),[16] developed a taxonomy for describing leadership situations, taxonomy that was used in a normative decision model where leadership styles where connected to situational variables, defining which approach was more suitable to which situation.[17] This approach was novel because it supported the idea that the same manager could rely on different group decision making approaches depending on the attributes of each situation. This model was later referred as situational contingency theory.[18]

The path-goal theory of leadership was developed by Robert House (1971) and was based on the expectancy theory of Victor Vroom.[19] According to House, the essence of the theory is "the meta proposition that leaders, to be effective, engage in behaviors that complement subordinates' environments and abilities in a manner that compensates for deficiencies and is instrumental to subordinate satisfaction and individual and work unit performance.[20] The theory identifies four leader behaviors, achievement-oriented, directive, participative, and supportive, that are contingent to the environment factors and follower characteristics. In contrast to the Fiedler contingency model, the path-goal model states that the four leadership behaviors are fluid, and that leaders can adopt any of the four depending on what the situation demands. The path-goal model can be classified both as a contingency theory, as it depends on the circumstances, but also as a transactional leadership theory, as the theory emphasizes the reciprocity behavior between the leader and the followers.

The situational leadership model proposed by Hersey and Blanchard suggest four leadership-styles and four levels of follower-development. For effectiveness, the model posits that the leadership-style must match the appropriate level of followership-development. In this model, leadership behavior becomes a function not only of the characteristics of the leader, but of the characteristics of followers as well.[21]

Functional theory

Functional leadership theory (Hackman & Walton, 1986; McGrath, 1962) is a particularly useful theory for addressing specific leader behaviors expected to contribute to organizational or unit effectiveness. This theory argues that the leader’s main job is to see that whatever is necessary to group needs is taken care of; thus, a leader can be said to have done their job well when they have contributed to group effectiveness and cohesion (Fleishman et al., 1991; Hackman & Wageman, 2005; Hackman & Walton, 1986). While functional leadership theory has most often been applied to team leadership (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001), it has also been effectively applied to broader organizational leadership as well (Zaccaro, 2001). In summarizing literature on functional leadership (see Kozlowski et al. (1996), Zaccaro et al. (2001), Hackman and Walton (1986), Hackman & Wageman (2005), Morgeson (2005)), Klein, Zeigert, Knight, and Xiao (2006) observed five broad functions a leader provides when promoting unit effectiveness. These functions include: (1) environmental monitoring, (2) organizing subordinate activities, (3) teaching and coaching subordinates, (4) motivating others, and (5) intervening actively in the group’s work.

A variety of leadership behaviors are expected to facilitate these functions. In initial work identifying leader behavior, Fleishman (Fleishman, 1953) observed that subordinates perceived their supervisors’ behavior in terms of two broad categories referred to as consideration and initiating structure. Consideration includes behavior involved in fostering effective relationships. Examples of such behavior would include showing concern for a subordinate or acting in a supportive manner towards others. Initiating structure involves the actions of the leader focused specifically on task accomplishment. This could include role clarification, setting performance standards, and holding subordinates accountable to those standards.

Transactional and transformational theories

The transactional leader (Burns, 1978)[22] is given power to perform certain tasks and reward or punish for the team’s performance. It gives the opportunity to the manager to lead the group and the group agrees to follow his lead to accomplish a predetermined goal in exchange for something else. Power is given to the leader to evaluate, correct and train subordinates when productivity is not up to the desired level and reward effectiveness when expected outcome is reached.

The transformational leader (Burns, 2008)[22] motivates its team to be effective and efficient. Communication is the base for goal achievement focusing the group on the final desired outcome or goal attainment. This leader is highly visible and uses chain of command to get the job done. Transformational leaders focus on the big picture, needing to be surrounded by people who take care of the details. The leader is always looking for ideas that move the organization to reach the company’s vision.

Leadership and emotions

Leadership can be perceived as a particularly emotion-laden process, with emotions entwined with the social influence process[23]. In an organization, the leaders’ mood has some effects on his group. These effects can be described in 3 levels[24]:

- The mood of individual group members. Group members with leaders in a positive mood experience more positive mood than do group members with leaders in a negative mood.The leaders transmit their moods to other group members through the mechanism of mood contagion[24].Mood contagion may be one of the psychological mechanisms by which charismatic leaders influence followers[25].

- The affective tone of the group. Group affective tone represents the consistent or homogeneous affective reactions within a group. Group affective tone is an aggregate of the moods of the individual members of the group and refers to mood at the group level of analysis. Groups with leaders in a positive mood have a more positive affective tone than do groups with leaders in a negative mood [24].

- Group processes like coordination, effort expenditure, and task strategy.Public expressions of mood impact how group members think and act. When people experience and express mood, they send signals to others. Leaders signal their goals, intentions, and attitudes through their expressions of moods. For example, expressions of positive moods by leaders signal that leaders deem progress toward goals to be good.The group members respond to those signals cognitively and behaviorally in ways that are reflected in the group processes [24].

In research about client service it was found that expressions of positive mood by the leader improve the performance of the group, although in other sectors there were another findings[26].

Beyond the leader’s mood, his behavior is a source for employee positive and negative emotions at work. The leader creates situations and events that lead to emotional response. Certain leader behaviors displayed during interactions with their employees are the sources of these affective events. Leaders shape workplace affective events. Examples – feedback giving, allocating tasks, resource distribution. Since employee behavior and productivity are directly affected by their emotional states, it is imperative to consider employee emotional responses to organizational leaders[27]. Emotional intelligence, the ability to understand and manage moods and emotions in the self and others, contributes to effective leadership in organizations[26]. Leadership is about being responsible.

Leadership performance

In the past, some researchers have argued that the actual influence of leaders on organizational outcomes is overrated and romanticized as a result of biased attributions about leaders (Meindl & Ehrlich, 1987). Despite these assertions however, it is largely recognized and accepted by practitioners and researchers that leadership is important, and research supports the notion that leaders do contribute to key organizational outcomes (Day & Lord, 1988; Kaiser, Hogan, & Craig, 2008). In order to facilitate successful performance it is important to understand and accurately measure leadership performance.

Job performance generally refers to behavior that is expected to contribute to organizational success (Campbell, 1990). Campbell identified a number of specific types of performance dimensions; leadership was one of the dimensions that he identified. There is no consistent, overall definition of leadership performance (Yukl, 2006). Many distinct conceptualizations are often lumped together under the umbrella of leadership performance, including outcomes such as leader effectiveness, leader advancement, and leader emergence (Kaiser et al., 2008). For instance, leadership performance may be used to refer to the career success of the individual leader, performance of the group or organization, or even leader emergence. Each of these measures can be considered conceptually distinct. While these aspects may be related, they are different outcomes and their inclusion should depend on the applied/research focus.

Contexts of leadership

Leadership in organizations

An organization that is established as an instrument or means for achieving defined objectives has been referred to as a formal organization. Its design specifies how goals are subdivided and reflected in subdivisions of the organization. Divisions, departments, sections, positions, jobs, and tasks make up this work structure. Thus, the formal organization is expected to behave impersonally in regard to relationships with clients or with its members. According to Weber's definition, entry and subsequent advancement is by merit or seniority. Each employee receives a salary and enjoys a degree of tenure that safeguards him from the arbitrary influence of superiors or of powerful clients. The higher his position in the hierarchy, the greater his presumed expertise in adjudicating problems that may arise in the course of the work carried out at lower levels of the organization. It is this bureaucratic structure that forms the basis for the appointment of heads or chiefs of administrative subdivisions in the organization and endows them with the authority attached to their position. [28]

In contrast to the appointed head or chief of an administrative unit, a leader emerges within the context of the informal organization that underlies the formal structure. The informal organization expresses the personal objectives and goals of the individual membership. Their objectives and goals may or may not coincide with those of the formal organization. The informal organization represents an extension of the social structures that generally characterize human life — the spontaneous emergence of groups and organizations as ends in themselves.

In prehistoric times, man was preoccupied with his personal security, maintenance, protection, and survival. Now man spends a major portion of his waking hours working for organizations. His need to identify with a community that provides security, protection, maintenance, and a feeling of belonging continues unchanged from prehistoric times. This need is met by the informal organization and its emergent, or unofficial, leaders.[29]

Leaders emerge from within the structure of the informal organization. Their personal qualities, the demands of the situation, or a combination of these and other factors attract followers who accept their leadership within one or several overlay structures. Instead of the authority of position held by an appointed head or chief, the emergent leader wields influence or power. Influence is the ability of a person to gain co-operation from others by means of persuasion or control over rewards. Power is a stronger form of influence because it reflects a person's ability to enforce action through the control of a means of punishment.[29]

A leader is anyone who influences a group toward obtaining a particular result. It is not dependant on title or formal authority. (elevos, paraphrased from Leaders, Bennis, and Leadership Presence, Halpern & Lubar). Leaders are recognized by their capacity for caring for others, clear communication, and a commitment to persist. [30]An individual who is appointed to a managerial position has the right to command and enforce obedience by virtue of the authority of his position. However, he must possess adequate personal attributes to match his authority, because authority is only potentially available to him. In the absence of sufficient personal competence, a manager may be confronted by an emergent leader who can challenge his role in the organization and reduce it to that of a figurehead. However, only authority of position has the backing of formal sanctions. It follows that whoever wields personal influence and power can legitimize this only by gaining a formal position in the hierarchy, with commensurate authority.[29] Leadership can be defined as one's ability to get others to willingly follow. Every organization needs leaders at every level.[31]

Leadership versus management

Over the years the terms management and leadership have been so closely related that individuals in general think of them as synonymous. However, this is not the case even considering that good managers have leadership skills and vice-versa. With this concept in mind, leadership can be viewed as:

- centralized or decentralized

- broad or focused

- decision-oriented or morale-centred

- intrinsic or derived from some authority

Any of the bipolar labels traditionally ascribed to management style could also apply to leadership style. Hersey and Blanchard use this approach: they claim that management merely consists of leadership applied to business situations; or in other words: management forms a sub-set of the broader process of leadership. They put it this way: "Leadership occurs any time one attempts to influence the behavior of an individual or group, regardless of the reason.Management is a kind of leadership in which the achievement of organizational goals is paramount." "And according to Warren Bennis and Dan Goldsmith, A good manager does things right. A leader does the right things."[32]

However, a clear distinction between management and leadership may nevertheless prove useful. This would allow for a reciprocal relationship between leadership and management, implying that an effective manager should possess leadership skills, and an effective leader should demonstrate management skills. One clear distinction could provide the following definition:

- Management involves power by position.

- Leadership involves power by influence.

Abraham Zaleznik (1977),for example, delineated differences between leadership and management. He saw leaders as inspiring visionaries, concerned about substance; while managers he views as planners who have concerns with process.Warren Bennis (1989) further explicated a dichotomy between managers and leaders. He drew twelve distinctions between the two groups:

- Managers administer, leaders innovate

- Managers ask how and when, leaders ask what and why

- Managers focus on systems, leaders focus on people

- Managers do things right, leaders do the right things

- Managers maintain, leaders develop

- Managers rely on control, leaders inspire trust

- Managers have a short-term perspective, leaders have a longer-term perspective

- Managers accept the status-quo, leaders challenge the status-quo

- Managers have an eye on the bottom line, leaders have an eye on the horizon

- Managers imitate, leaders originate

- Managers emulate the classic good soldier, leaders are their own person

- Managers copy, leaders show originality

Paul Birch (1999) also sees a distinction between leadership and management. He observed that, as a broad generalization, managers concerned themselves with tasks while leaders concerned themselves with people. Birch does not suggest that leaders do not focus on "the task." Indeed, the things that characterise a great leader include the fact that they achieve. Effective leaders create and sustain competitive advantage through the attainment of cost leadership, revenue leadership, time leadership, and market value leadership. Managers typically follow and realize a leader's vision. The difference lies in the leader realising that the achievement of the task comes about through the goodwill and support of others (influence), while the manager may not.

This goodwill and support originates in the leader seeing people as people, not as another resource for deployment in support of "the task". The manager often has the role of organizing resources to get something done. People form one of these resources, and many of the worst managers treat people as just another interchangeable item. A leader has the role of causing others to follow a path he/she has laid out or a vision he/she has articulated in order to achieve a task. Often, people see the task as subordinate to the vision. For instance, an organization might have the overall task of generating profit, but a good leader may see profit as a by-product that flows from whatever aspect of their vision differentiates their company from the competition.

Leadership does not only manifest itself as purely a business phenomenon. Many people can think of an inspiring leader they have encountered who has nothing whatever to do with business: a politician, an officer in the armed forces, a Scout or Guide leader, a teacher, etc. Similarly, management does not occur only as a purely business phenomenon. Again, we can think of examples of people that we have met who fill the management niche in non-business organisationsNon-business organizations should find it easier to articulate a non-money-driven inspiring vision that will support true leadership. However, often this does not occur.

Differences in the mix of leadership and management can define various management styles. Some management styles tend to de-emphasize leadership. Included in this group one could include participatory management, democratic management, and collaborative management styles. Other management styles, such as authoritarian management, micro-management, and top-down management, depend more on a leader to provide direction. Note, however, that just because an organisation has no single leader giving it direction, does not mean it necessarily has weak leadership. In many cases group leadership (multiple leaders) can prove effective. Having a single leader (as in dictatorship) allows for quick and decisive decision-making when needed as well as when not needed. Group decision-making sometimes earns the derisive label "committee-itis" because of the longer times required to make decisions, but group leadership can bring more expertise, experience, and perspectives through a democratic process.

Patricia Pitcher (1994) has challenged the bifurcation into leaders and managers. She used a factor analysis (in marketing)factor analysis technique on data collected over 8 years, and concluded that three types of leaders exist, each with very different psychological profiles:'Artists' imaginative, inspiring, visionary, entrepreneurial, intuitive, daring, and emotional Craftsmen: well-balanced, steady, reasonable, sensible, predictable, and trustworthy Technocrats: cerebral, detail-oriented, fastidious, uncompromising, and hard-headed She speculates that no one profile offers a preferred leadership style. She claims that if we want to build, we should find an "artist leader" if we want to solidify our position, we should find a "craftsman leader" and if we have an ugly job that needs to get done like downsizing.we should find a "technocratic leader".Pitcher also observed that a balanced leader exhibiting all three sets of traits occurs extremely rarely: she found none in her study.

Bruce Lynn postulates a differentiation between 'Leadership' and ‘Management’ based on perspectives to risk. Specifically,"A Leader optimises upside opportunity; a Manager minimises downside risk." He argues that successful executives need to apply both disciplines in a balance appropriate to the enterprise and its context. Leadership without Management yields steps forward, but as many if not more steps backwards. Management without Leadership avoids any step backwards, but doesn’t move forward.

Leadership by a group

In contrast to individual leadership, some organizations have adopted group leadership. In this situation, more than one person provides direction to the group as a whole. Some organizations have taken this approach in hopes of increasing creativity, reducing costs, or downsizing. Others may see the traditional leadership of a boss as costing too much in team performance. In some situations, the maintenance of the boss becomes too expensive - either by draining the resources of the group as a whole, or by impeding the creativity within the team, even unintentionally.[citation needed]

A common example of group leadership involves cross-functional teams. A team of people with diverse skills and from all parts of an organization assembles to lead a project. A team structure can involve sharing power equally on all issues, but more commonly uses rotating leadership. The team member(s) best able to handle any given phase of the project become(s) the temporary leader(s). According to Ogbonnia (2007), "effective leadership is the ability to successfully integrate and maximize available resources within the internal and external environment for the attainment of organizational or societal goals". Ogbonnia defines an effective leader "as an individual with the capacity to consistently succeed in a given condition and be recognized as meeting the expectations of an organization or society." Additionally, as each team member has the opportunity to experience the elevated level of empowerment, it energizes staff and feeds the cycle of success. [33]

Leaders who demonstrate persistence, tenacity, determination and synergistic communication skills will bring out the same qualities in their groups. Good leaders use their own inner mentors to energize their team and organizations and lead a team to achieve success.[34]

Leadership among primates

Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson, in Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence present evidence that only humans and chimpanzees, among all the animals living on earth, share a similar tendency for a cluster of behaviors: violence, territoriality, and competition for uniting behind the one chief male of the land. [1] This position is contentious. Many animals beyond apes are territorial, compete, exhibit violence, and have a social structure controlled by a dominant male (lions, wolves, etc.), suggesting Wrangham and Peterson's evidence is not empirical. However, we must examine other species as well, including elephants (which are undoubtedly matriarchal and follow an alpha female), meerkats (who are likewise matriarchal), and many others.

It would be beneficial, to examine that most accounts of leadership over the past few millennia (since the creation of Christian religions) are through the perspective of a patriarchal society, founded on Christian literature. If one looks before these times, it is noticed that Pagan and Earth-based tribes in fact had female leaders. It is important also to note that the peculiarities of one tribe cannot necessarily be ascribed to another, as even our modern-day customs differ. The current day patrilineal custom is only a recent invention in human history and our original method of familial practices were matrilineal (Dr. Christopher Shelley and Bianca Rus, UBC). The fundamental assumption that has been built into 90% of the world's countries is that patriarchy is the 'natural' biological predisposition of homo sapiens. Unfortunately, this belief has led to the widespread oppression of women in all of those countries, but in varying degrees. (Whole Earth Review, Winter, 1995 by Thomas Laird, Michael Victor). The Iroquoian First Nations tribes are an example of a matrilineal tribe, along with Mayan tribes, and also the society of Meghalaya, India. (Laird and Victor, 1995).

By comparison, bonobos, the second-closest species-relatives of man, do not unite behind the chief male of the land. The bonobos show deference to an alpha or top-ranking female that, with the support of her coalition of other females, can prove as strong as the strongest male in the land. Thus, if leadership amounts to getting the greatest number of followers, then among the bonobos, a female almost always exerts the strongest and most effective leadership. However, not all scientists agree on the allegedly "peaceful" nature of the bonobo or its reputation as a "hippie chimp".[2]

Historical views on leadership

Sanskrit literature identifies ten types of leaders. Defining characteristics of the ten types of leaders are explained with examples from history and mythology.[35]

Aristocratic thinkers have postulated that leadership depends on one's blue blood or genes: monarchy takes an extreme view of the same idea, and may prop up its assertions against the claims of mere aristocrats by invoking divine sanction: see the divine right of kings. Contrariwise, more democratically-inclined theorists have pointed to examples of meritocratic leaders, such as the Napoleonic marshals profiting from careers open to talent.

In the autocratic/paternalistic strain of thought, traditionalists recall the role of leadership of the Roman pater familias. Feminist thinking, on the other hand, may damn such models as patriarchal and posit against them emotionally-attuned, responsive, and consensual empathetic guidance and matriarchies.

Comparable to the Roman tradition, the views of Confucianism on "right living" relate very much to the ideal of the (male) scholar-leader and his benevolent rule, buttressed by a tradition of filial piety.

Within the context of Islam, views on the nature, scope and inheritance of leadership have played a major role in shaping sects and their history. See caliphate.

In the 19th century, the elaboration of anarchist thought called the whole concept of leadership into question. (Note that the Oxford English Dictionary traces the word "leadership" in English only as far back as the 19th century.) One response to this denial of élitism came with Leninism, which demanded an élite group of disciplined cadres to act as the vanguard of a socialist revolution, bringing into existence the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Other historical views of leadership have addressed the seeming contrasts between secular and religious leadership. The doctrines of Caesaro-papism have recurred and had their detractors over several centuries. Christian thinking on leadership has often emphasized stewardship of divinely-provided resources - human and material - and their deployment in accordance with a Divine plan. Compare servant leadership.

For a more general take on leadership in politics, compare the concept of the statesman.

Titles emphasizing authority

At certain stages in their development, the hierarchies of social ranks implied different degrees or ranks of leadership in society. Thus a knight led fewer men in general than did a duke; a baronet might in theory control less land than an earl. See peerage for a systematization of this hierarchy, and order of precedence for links to various systems.

In the course of the 18th and 20th centuries, several political operators took non-traditional paths to become dominant in their societies. They or their systems often expressed a belief in strong individual leadership, but existing titles and labels ("King", "Emperor", "President" and so on) often seemed inappropriate, insufficient or downright inaccurate in some circumstances. The formal or informal titles or descriptions they or their flunkies employe express and foster a general veneration for leadership of the inspired and autocratic variety. The definite article when used as part of the title (in languages which use definite articles) emphasizes the existence of a sole "true" leader.

Criticism of the concept of leadership

Noam Chomsky has criticized the concept of leadership as involving people subordinating their needs to that of someone else. While the conventional view of leadership is rather satisfying to people who "want to be told what to do", one should question why they are being subjected to acts that may not be rational or even desirable. Rationality is the key element missing when "leaders" say "believe me" and "have faith". It is fairly easy to have people simplistically follow their "leader", if no attention is paid to rationality.[citation needed]. This view of Chomsky is related to his Weltanschaung and has no solid psychological basis from the consensus of the establishment.

See also

|

|

|

|

References

- Notes

- ^ Chemers, M. M. (2002). Cognitive, social, and emotional intelligence of transformational leadership: Efficacy and Effectiveness. In R. E. Riggio, S. E. Murphy, F. J. Pirozzolo (Eds.), Multiple Intelligences and Leadership.}

- ^ Kouzes, J., and Posner, B. (2007). The Leadership Challenge. CA: Jossey Bass.

- ^ a b Locke et. al 1991

- ^ (Richards & Engle, 1986, p.206)

- ^ Carlyle (1841)

- ^ Heifetz (1994), pp. 16

- ^ Spillane (2004)

- ^ a b Lewin et. al (1939)

- ^ Miner (2005) pp. 39-40

- ^ Blake et. al (1964)

- ^ Spencer (1884), apud Heifetz (1994), pp. 16

- ^ Hemphill (1949)

- ^ Wormer et. al (2007), pp: 198

- ^ Fiedler (1967)

- ^ Vroom, Yetton (1973)

- ^ Vroom, Jago (1988)

- ^ Sternberg, Vroom (2002)

- ^ Lorsch (1974)

- ^ House (1971)

- ^ House (1996)

- ^ Hersey et. al (2008)

- ^ a b Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper and Row Publishers Inc.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ George J.M. 2000. Emotions and leadership: The role of emotional intelligence, Human Relations 53 (2000), pp. 1027–1055

- ^ a b c d Sy, T. & Cote, S & Saavedra R. 2005. The contagious leader: Impact of the leader’s mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2): pp. 295-305. http://www.rotman.utoronto.ca/~scote/SyetalJAP.pdf

- ^ Bono J.E. & Ilies R. 2006 Charisma, positive emotions and mood contagion. The Leadership Quarterly 17(4): pp. 317-334

- ^ a b George J.M. 2006. Leader Positive Mood and Group Performance: The Case of Customer Service. Journal of Applied Social Psychology :25(9) pp. 778 - 794

- ^ Dasborough M.T. 2006.Cognitive asymmetry in employee emotional reactions to leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 17(2):pp. 163-178

- ^ Cecil A Gibb (1970). Leadership (Handbook of Social Psychology). Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. pp. 884–89. ISBN 0140805176 9780140805178. OCLC 174777513.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b c Henry P. Knowles; Borje O. Saxberg (1971). Personality and Leadership Behavior. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. pp. 884–89. ISBN 0140805176 9780140805178. OCLC 118832.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoyle, John R. Leadership and Futuring: Making Visions Happen. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc., 1995.

- ^ The Top 10 Leadership Qualities - HR World

- ^ Bennis, Warren and Dan Goldsmith. Learning to Lead. Massachusetts: Persus Book, 1997.

- ^ Ingrid Bens (2006). Facilitating to Lead. Jossey-Bass.

- ^ Dr. Bart Barthelemy (1997). The Sky Is Not The Limit - Breakthrough Leadership. St. Lucie Press.

- ^ KSEEB. Sanskrit Text Book -9th Grade. Governament of Karnataka, India.

- Books

- Blake, R.; Mouton, J. (1964). The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Excellence. Houston: Gulf Publishing Co.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1841). On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Fiedler, Fred E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. McGraw-Hill: Harper and Row Publishers Inc.

- Heifetz, Ronald (1994). Leadership without Easy Answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-51858-6.

- Hemphill, John K. (1949). Situational Factors in Leadership. Columbus: Ohio State University Bureau of Educational Research.

- Hersey, Paul; Blanchard, Ken; Johnson, D. (2008). Management of Organizational Behavior: Leading Human Resources (9th ed. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Miner, J. B. (2005). Organizational Behavior: Behavior 1: Essential Theories of Motivation and Leadership. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

- Spencer, Herbert (1841). The Study of Sociology. New York: D. A. Appleton.

- Vroom, Victor H.; Yetton, Phillip W. (1973). Leadership and Decision-Making. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Vroom, Victor H.; Jago, Arthur G. (1988). The New Leadership: Managing Participation in Organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Van Wormer, Katherine S.; Besthorn, Fred H.; Keefe, Thomas (2007). Human Behavior and the Social Environment: Macro Level: Groups, Communities, and Organizations. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195187547.

- Journal articles

- House, Robert J. (1971). "A path-goal theory of leader effectiveness". Administrative Science Quarterly. Vol.16: 321–339.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - House, Robert J. (1996). "Path-goal theory of leadership: Lessons, legacy, and a reformulated theory". Leadership Quarterly. Vol.7 (3): 323–352.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Lewin, Kurt; Lippitt, Ronald; White, Ralph (1939). "Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates". Journal of Social Psychology: 271–301.

- Kirkpatrick, S.A., (1991). "Leadership: Do traits matter?". Academy of Management Executive. Vol. 5, No. 2.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help);|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lorsch, Jay W. (Spring 1974). "Review of Leadership and Decision Making". Sloan Management Review.

- Spillane, James P.; et al. (2004). "Towards a theory of leadership practice". Journal of Curriculum Studies. Vol. 36, No. 1: 3-34.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - Vroom, Victor; Sternberg, Robert J. (2002). "Theoretical Letters: The person versus the situation in leadership". The Leadership Quarterly. Vol. 13: 301-323.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

External links

- Leadership at Curlie