Tarot: Difference between revisions

typo |

m current article name |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

==Occult tarot and divination== |

==Occult tarot and divination== |

||

{{main| |

{{main|Tarot (cartomancy)}} |

||

Tarot cards would later become associated with [[mysticism]] and [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]].<ref>Huson, Paul ''Mystical Origins of the Tarot: From Ancient Roots to Modern Usage''. Vermont: Destiny Books, 2004</ref> Tarot was not widely adopted by mystics, occultists and secret societies until the 18th and 19th centuries. The tradition began in 1781, when [[Antoine Court de Gebelin|Antoine Court de Gébelin]], a [[Switzerland|Swiss]] [[clergy]]man and [[Freemasonry|Freemason]], published ''Le Monde Primitif'', a speculative study which included religious [[symbolism]] and its survivals in the modern world. De Gébelin first asserted that symbolism of the ''[[Tarot de Marseille]]'' represented the [[Western mystery traditions|mysteries]] of [[Isis]] and [[Thoth]]. Gébelin further claimed that the name "tarot" came from the [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] words ''tar'', meaning "royal", and ''ro'', meaning "road", and that the Tarot therefore represented a "royal road" to wisdom. De Gébelin also asserted that the [[Gypsy|Gypsies]], who were among the first to use cards for divination, were descendants of the Ancient Egyptians (hence their common name; though by this time it was more popularly used as a [[stereotype]] for any nomadic tribe) and had introduced the cards to Europe. De Gébelin wrote this treatise before [[Jean-François Champollion]] had deciphered [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s, or indeed before the [[Rosetta Stone]] had been discovered, and later [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] found nothing in the Egyptian language to support de Gébelin's fanciful [[etymology|etymologies]]. Despite this, the identification of the Tarot cards with the Egyptian "Book of Thoth" was already firmly established in occult practice and continues in modern [[urban legend]] to the present day. |

Tarot cards would later become associated with [[mysticism]] and [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]].<ref>Huson, Paul ''Mystical Origins of the Tarot: From Ancient Roots to Modern Usage''. Vermont: Destiny Books, 2004</ref> Tarot was not widely adopted by mystics, occultists and secret societies until the 18th and 19th centuries. The tradition began in 1781, when [[Antoine Court de Gebelin|Antoine Court de Gébelin]], a [[Switzerland|Swiss]] [[clergy]]man and [[Freemasonry|Freemason]], published ''Le Monde Primitif'', a speculative study which included religious [[symbolism]] and its survivals in the modern world. De Gébelin first asserted that symbolism of the ''[[Tarot de Marseille]]'' represented the [[Western mystery traditions|mysteries]] of [[Isis]] and [[Thoth]]. Gébelin further claimed that the name "tarot" came from the [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] words ''tar'', meaning "royal", and ''ro'', meaning "road", and that the Tarot therefore represented a "royal road" to wisdom. De Gébelin also asserted that the [[Gypsy|Gypsies]], who were among the first to use cards for divination, were descendants of the Ancient Egyptians (hence their common name; though by this time it was more popularly used as a [[stereotype]] for any nomadic tribe) and had introduced the cards to Europe. De Gébelin wrote this treatise before [[Jean-François Champollion]] had deciphered [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s, or indeed before the [[Rosetta Stone]] had been discovered, and later [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] found nothing in the Egyptian language to support de Gébelin's fanciful [[etymology|etymologies]]. Despite this, the identification of the Tarot cards with the Egyptian "Book of Thoth" was already firmly established in occult practice and continues in modern [[urban legend]] to the present day. |

||

Revision as of 15:31, 19 July 2009

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

The tarot (first known as tarocchi, also tarock and similar names), Template:PronEng, is a pack of seventy-eight cards, used from the mid fifteenth century in various parts of Europe to play card games such as Italian Tarocchini and French Tarot. It has four suits corresponding to the four suits of the modern 52-card pack, though the suit symbols and the number of court cards differ. It is distinguished also by a separate 21-card trump suit and a card known in English as the Fool which may act as the top trump or may be played to avoid following suit, depending on the game.[1]

Rabelais gives tarau as the name of one of the games played by Gargantua in his Gargantua and Pantagruel[2]; this is likely the earliest attestation of the French form of the name. Tarot cards are used throughout much of Europe to play card games. In English-speaking countries, where these games are largely unknown, Tarot cards are now used primarily for divinatory purposes.[1][3] Occultists call the trump cards and the Fool "the major arcana" while the ten pip and four court cards in each suit are called minor arcana. The cards are traced by some occult writers to ancient Egypt or the Kabbalah but there is no documented evidence of such origins or of the usage of tarot for divination before the eighteenth century.[1]

Etymology

The English and French word tarot derives from the Italian tarocchi, which has no known origin or etymology. One theory relates the name "tarot" to the Taro River in northern Italy, near Parma; the game seems to have originated in northern Italy, in Milan or Bologna.[4] Other writers believe it comes from the Arabic word turuq, related to "tariq" which means "way".[5] Alternatively, it may be from the Arabic tarach,[6] "reject". According to a French etymology, the Italian tarocco derived from tara:[7] "devaluation of a merchandise; deduction, the act of deducting".

History

Playing cards first entered Europe in the late 14th century, probably from Mamluk Egypt, with suits very similar to the Tarot suits of Swords, Staves, Cups and Coins (also known as disks, and pentacles) and those still used in traditional Italian, Spanish and Portuguese decks.[8] The first documentary evidence is a ban on their use in 1367, Bern, Switzerland. Wide use of playing cards in Europe can, with some certainty, be traced from 1377 onwards.[9]

The first known Tarot cards were created between 1430 and 1450 in Milan, Ferrara and Bologna in northern Italy when additional trump cards with allegorical illustrations were added to the common four-suit pack. These new decks were originally called carte da trionfi, triumph cards, and the additional cards known simply as trionfi, which became "trumps" in English. The first literary evidence of the existence of carte da trionfi is a written statement in the court records in Ferrara, in 1442.[10] The oldest surviving Tarot cards are from fifteen fragmented decks painted in the mid 15th century for the Visconti-Sforza family, the rulers of Milan.[11]

Divination using playing cards is in evidence as early as 1540 in a book entitled The Oracles of Francesco Marcolino da Forli which allows a simple method of divination, though the cards are used only to select a random oracle and have no meaning in themselves. But manuscripts from 1735 (The Square of Sevens) and 1750 (Pratesi Cartomancer) document rudimentary divinatory meanings for the cards of the tarot as well as a system for laying out the cards. In 1765, Giacomo Casanova wrote in his diary that his Russian mistress frequently used a deck of playing cards for divination.[12]

Early decks

Picture-card packs are first mentioned by Martiano da Tortona probably between 1418 and 1425, since in 1418 the painter he mentions, Michelino da Besozzo, returned to Milan while Martiano himself died in 1425. He describes a deck with sixteen picture cards with images of the Greek gods and suits depicting four kinds of birds, not the common suits. However the sixteen cards were obviously regarded as "trumps" as, about twenty-five years later, Jacopo Antonio Marcello called them a ludus triumphorum, or "game of trumps".[13]

Special motifs on cards added to regular packs show philosophical, social, poetical, astronomical, and heraldic ideas, Roman/Greek/Babylonian heroes, as in the case of the Sola-Busca-Tarocchi (1491)[citation needed] and the Boiardo Tarocchi poem (produced at an unknown date between 1461 and 1494).[citation needed]

Two playing card decks from Milan ( the Brera-Brambrilla and Cary-Yale-Tarocchi)—extant, but fragmentary—were made circa 1440. Three documents dating from 1 January 1441 to July 1442, use the term trionfi. The document from January 1441 is regarded as an unreliable reference; however, the same painter, Sagramoro, was commissioned by the same patron, Leonello d'Este, as in the February 1442 document. The game seemed to gain in importance in the year 1450, a Jubilee year in Italy, which saw many festivities and the movement of many pilgrims.

Three mid-15th century sets were made for members of the Visconti family[citation needed]. The first deck is called the Cary-Yale Tarot (or Visconti-Modrone Tarot), created between 1442 and 1447 by an anonymous painter for Filippo Maria Visconti[citation needed]. The cards (only sixty-six) are today in the Yale University Library of New Haven. The most famous was painted in the mid 15th century, to celebrate Francesco Sforza and his wife Bianca Maria Visconti, daughter of the duke Filippo Maria. Probably, these cards were painted by Bonifacio Bembo[citation needed]. Of the original cards, thirty-five are in the Pierpont Morgan Library, twenty-six are at the Accademia Carrara, thirteen are at the Casa Colleoni and two, 'The Devil' and 'The Tower', are lost or else never made. This "Visconti-Sforza" deck, which has been widely reproduced, reflects conventional iconography of the time to a significant degree.[14]

Hand-painted tarot cards remained a privilege of the upper classes and, although some sermons inveighing against the evil inherent in cards can be traced to the 14th century, most civil governments did not routinely condemn tarot cards during tarot's early history[citation needed]. In fact, in some jurisdictions, tarot cards were specifically exempted from laws otherwise prohibiting the playing of cards.

Because the earliest tarot cards were hand painted, the number of the decks produced is thought to have been rather small, and it was only after the invention of the printing press that mass production of cards became possible. Decks survive from this era from various cities in France (the best known being a deck from the southern city of Marseilles and thus named the Tarot de Marseilles). At around the same time, the name tarocchi appeared.[citation needed]

Tarot card games

The original purpose of tarot cards was for playing games, with the first basic rules appearing in the manuscript of Martiano da Tortona before 1425.[15] The game of Tarot is known in many variations (mostly cultural), first basic rules for the game of Tarocco appear in the manuscript of Martiano da Tortona (before 1425; translated text), the next are known from the year 1637. In Italy the game has become less popular, one version named Tarocco Bolognese: Ottocento has still survived and there are still others played in Piedmont, but the number of games outside of Italy is much higher. The French tarot game is the most popular in its native country and there are regional tarot games often known as tarock,tarok,or tarokk widely played in central Europe.

Occult tarot and divination

Tarot cards would later become associated with mysticism and magic.[16] Tarot was not widely adopted by mystics, occultists and secret societies until the 18th and 19th centuries. The tradition began in 1781, when Antoine Court de Gébelin, a Swiss clergyman and Freemason, published Le Monde Primitif, a speculative study which included religious symbolism and its survivals in the modern world. De Gébelin first asserted that symbolism of the Tarot de Marseille represented the mysteries of Isis and Thoth. Gébelin further claimed that the name "tarot" came from the Egyptian words tar, meaning "royal", and ro, meaning "road", and that the Tarot therefore represented a "royal road" to wisdom. De Gébelin also asserted that the Gypsies, who were among the first to use cards for divination, were descendants of the Ancient Egyptians (hence their common name; though by this time it was more popularly used as a stereotype for any nomadic tribe) and had introduced the cards to Europe. De Gébelin wrote this treatise before Jean-François Champollion had deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, or indeed before the Rosetta Stone had been discovered, and later Egyptologists found nothing in the Egyptian language to support de Gébelin's fanciful etymologies. Despite this, the identification of the Tarot cards with the Egyptian "Book of Thoth" was already firmly established in occult practice and continues in modern urban legend to the present day.

Other uses of Tarot

Literature

Tarot was used as early as the 16th century to compose poems, called "tarocchi appropriati", describing ladies of the court or famous personages. In modern literature, two exceptional examples of novels centered on the Tarot are The Greater Trumps (1932) by Charles Williams and Il Castello dei destinati incrociati (1969) (English translation: The Castle of Crossed Destinies [1979]) by Italo Calvino. In the former, the Tarot is used by the main characters to move through space and time, create matter, and raise powerful natural storms. In the latter, Mediaeval travellers meeting at a castle are inexplicably unable to speak, and use a Tarot deck to describe their stories, which are reconstructed by the narrator, calling forth implications of the nature of communication, fate, and the presence of the transcendent in daily life. Tarots also appear in T.S. Eliot's modernist poem The Waste Land (1922), in connection with the figure of Madame Sosostris, one of the characters which appear in the first part, "The Burial of the Dead". Some of the cards mentioned in the poem really exist in the tarot deck (the Hanged Man, the Wheel), some have been invented by Eliot. The 2007 novel Sepulchre by British author Kate Mosse features a fictional Tarot deck.

Psychological

Carl Jung was the first psychologist to attach importance to tarot symbolism. He may have regarded the tarot cards as representing archetypes: fundamental types of persons or situations embedded in the subconscious of all human beings. The theory of archetypes gives rise to several psychological uses. Since the cards represent these different archetypes within each individual, ideas of the subject's self-perception can be gained by asking them to select a card that they 'identify with'. Equally, the subject can try and clarify the situation by imagining it in terms of the archetypal ideas associated with each card. For instance, someone rushing in heedlessly like the Knight of Swords, or blindly keeping the world at bay like the Rider-Waite-Smith Two of Swords.

More recently Dr. Timothy Leary has suggested that the Tarot Trump cards are a pictorial representation of human development from a baby to a fully grown adult, The Fool symbolizing the new born infant, The Magician symbolizing the stage at which an infant starts to play with artifacts, etc. In addition to this, in Leary's view the Tarot Trumps can be seen to be a blue print for of the human race in the future as it matures.

Varieties of tarot deck designs

A variety of styles of tarot decks and designs exist and a number of typical regional patterns have emerged. Historically, one of the most important designs is the one usually known as the Tarot de Marseilles. This standard pattern was the one studied by Court de Gébelin, and cards based on this style illustrate his Le Monde primitif. The Tarot de Marseilles was also popularized in the 20th century by Paul Marteau[citation needed]. Some current editions of cards based on the Marseilles design go back to a deck of a particular Marseilles design that was printed by Nicolas Conver in 1760. Other regional styles include the "Swiss" Tarot; this one substitutes Juno and Jupiter for the Papess, or High Priestess and the Pope, or Hierophant. In Florence an expanded deck called Minchiate was used; this deck of ninety six cards includes astrological symbols including the four elements, as well as traditional Tarot motifs.

Some decks exist primarily as artwork; and such art decks sometimes contain only the twenty two trump cards.

French suited tarots

French suited tarot cards began to appear in Germany during 18th century. The first generation of French suited tarots depicted scenes of animals on the trumps and were thus called "Tiertarock" decks. Card maker Göbl of Munich is often credited for this design innovation. French suited tarot cards are a modern deck used for the tarot/tarock card games commonly played in France and central Europe. The symbolism of French suited tarot trumps depart considerably from the older Italian suited design. With very few exceptional cases such as the Tarocchi di Alan and the recent Tarot de la Nature, French suited tarot cards are nearly exclusively used for card games and rarely for divination.

Non-occult Italian-suited Tarot decks

These were the earliest form of Tarot deck to be invented, being first devised in the fifteenth century in northern Italy. The occult Tarot decks are based on decks of this type. Four decks of this category are still used to play certain games:

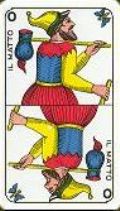

- The Tarocco Piemontese consists of the four suits of swords, batons, clubs and coins, each headed by a king, queen, cavalier and jack, followed by numerals 10 down to 1. The trumps rank as follows: The Angel (20—although it only bears the second-highest number, it is nonetheless the highest), the World (21), the Sun (19), the Moon (18), the Star (17), the Tower (16), the Devil (15), Temperance (14), death (13), the Hanged Man (12), Strength (11), the Wheel of Fortune (10), the Hermit (9), Justice (8), the Chariot (7), the Lovers (6), the Pope (5), the Emperor (4), the Empress (3), the Popess (2) and the Bagatto (1). There is also the Fool (Matto).

- The Swiss Tarot de Besançon is similar, but is of a different graphical design, and replaces the Pope with Jupiter, the Popess with Juno, and the Angel with the Judgement. The trumps rank in numerical order and the Tower is known as the House of God.

- The Tarocco Bolognese omits numeral cards two to five in plain suits, leaving it with 62 cards, and has somewhat different trumps, not all of which are numbered and four of which are equal in rank. It has a different graphical design.

- The Tarocco Siciliano changes some of the trumps, and replaces the 21 with a card labelled Miseria (destitution). It omits the Two and Three of coins, and numerals one to four in batons, swords and cups: it thus has 64 cards. The cards are quite small and, again, of a different graphical design.[9]

Occult tarot decks

Etteilla was the first to issue a revised tarot deck specifically designed for occult purposes rather than game playing. In keeping with the belief that tarot cards are derived from the Book of Thoth, Etteilla's tarot contained themes related to ancient Egypt. The seventy eight card tarot deck used by esotericists has two distinct parts:

- The Major Arcana (greater secrets), or trump cards, consists of twenty two cards without suits; The Fool, The Magician, The High Priestess, The Empress, The Emperor, The Hierophant, The Lovers, The Chariot, Strength, The Hermit, Wheel of Fortune, Justice, The Hanged Man, Death, Temperance, The Devil, The Tower, The Star, The Moon, The Sun, Judgement, and The World.

- The Minor Arcana (lesser secrets) consists of fifty six cards, divided into four suits of fourteen cards each; ten numbered cards and four court cards. The court cards are the King, Queen, Knight and Jack, in each of the four tarot suits. The traditional Italian tarot suits are swords, batons, coins and cups; in modern tarot decks, however, the batons suit is often called wands, rods or staves, while the coins suit is often called pentacles or disks.

The terms major arcana and minor arcana were first used by Jean Baptiste Pitois AKA Paul Christian and are never used in relation to Tarot card games.

Tarot is often used in conjunction with the study of the Hermetic Qabalah.[17] In these decks all the cards are illustrated in accordance with Qabalistic principles, most being under the influence of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck and bearing illustrated scenes on all the suit cards. The images on the 'Rider-Waite' deck were drawn by artist Pamela Colman-Smith, to the instructions of Christian mystic and occultist Arthur Edward Waite, and were originally published by the Rider Company in 1910. This deck is considered a simple, user friendly one but nevertheless its imagery, especially in the Major Arcana, is complex and replete with esoteric symbolism. The subjects of the Major Arcana are based on those of the earliest decks, but have been significantly modified to reflect Waite and Smith's view of Tarot. An important difference from Marseilles style decks is that Smith drew scenes with esoteric meanings on the suit cards. However the Rider-Waite wasn't the first deck to include completely illustrated suit cards. The first to do so was the 15th century Sola-Busca deck[citation needed].

Older decks such as the Visconti-Sforza and Marseilles are less detailed than modern esoteric decks. A Marseilles type deck is usually distinguished by having repetitive motifs on the pip cards, similar to Italian or Spanish playing cards, as opposed to the full scenes found on "Rider-Waite" style decks. These more simply illustrated "Marseilles" style decks are also used esoterically, for divination, and for game play, though the French card game of tarot is now generally played using a relatively modern 19th century design of German origin. Such playing tarot decks generally have twenty one trump cards with genre scenes from 19th century life, a Fool, and have court and pip cards that closely resemble today's French playing cards.)

The Marseilles style Tarot decks generally feature numbered minor arcana cards that look very much like the pip cards of modern playing card decks. The Marseilles' numbered minor arcana cards do not have scenes depicted on them; rather, they sport a geometric arrangement of the number of suit symbols (e.g., swords, rods/wands, cups, coins/pentacles) corresponding to the number of the card (accompanied by botanical and other non-scenic flourishes), while the court cards are often illustrated with flat, two-dimensional drawings.

A widely used modernist esoteric Tarot deck is Aleister Crowley's Thoth Tarot (Thoth pronounced /ˈtoʊt/ or /ˈθɒθ/). Crowley, at the height of a lifetime's work dedicated to occultism, engaged the artist Lady Frieda Harris to paint the cards for the deck according to his specifications. His system of Tarot correspondences, published in The Book of Thoth & Liber 777, are an evolution and expansion upon that which he learned in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn[citation needed].

In contrast to the Thoth deck's colorfulness, the illustrations on Paul Foster Case's B.O.T.A. Tarot deck are black line drawings on white cards; this is an unlaminated deck intended to be colored by its owner. Other esoteric decks include the Golden Dawn Tarot, which claims to be based on a deck by SL MacGregor Mathers.

The variety of decks presently available is almost endless, and grows yearly. For instance, cat-lovers may have the Tarot of the Cat People, a deck replete with cats in every picture. The Tarot of the Witches and the Aquarian Tarot retain the conventional cards with varying designs. The Tree of Life Tarot's cards are stark symbolic catalogs, the Cosmic Tarot, and The Alchemical Tarot that combines traditional alchemical symbols with tarot images.

These contemporary divination decks change the cards to varying degrees. For example, the Motherpeace Tarot is notable for its circular cards and feminist angle: the male characters have been replaced by females. The Tarot of Baseball has suits of bats, mitts, balls and bases; "coaches" and "MVPs" instead of Queens and Kings; and major arcana cards like "The Catcher", "The Rule Book" and "Batting a Thousand". In the Silicon Valley Tarot, major arcana cards include The Hacker, Flame War, The Layoff and The Garage; the suits are Networks, Cubicles, Disks and Hosts; the court cards CIO, Salesman, Marketeer and New Hire. Another tarot in recent years has been the Robin Wood Tarot. This deck retains the Rider-Waite theme while adding some very soft and colorful Pagan symbolism. As with other decks, the cards are available with a companion book written by Ms. Wood which details all of the symbolism and colors utilized in the Major and Minor Arcana.

Unconventionality is taken to an extreme by Morgan's Tarot, produced in 1970 by Morgan Robbins and illustrated by Darshan Chorpash Zenith. Morgan's Tarot has no suits, no card ranking and no explicit order of the cards. It has eighty eight cards rather than the more conventional seventy eight, and its simple line drawings show a strong influence from the psychedelic era. Nevertheless, in the introductory booklet that accompanies the deck (comprehensively mirrored on dfoley's website, with permission from U.S. Games Systems), Robbins claims spiritual inspiration for the cards and cites the influence of Tibetan Buddhism in particular.

Deck-specific symbolism

Many popular decks have modified the traditional symbolism to reflect the esoteric beliefs of their creators.

Rider-Waite-Smith-deck

The tarot created by A.E. Waite and Pamela Coleman Smith departs from the earlier tarot design with its use of scenic pip cards and the alteration of how the Strength and Justice cards are ranked.

Crowley-Harris Book of Thoth deck

Each card in the Thoth deck is intricately detailed with Astrological, Zodiacal, Elemental and Qabalistic symbols related to each card. Colours are used symbolically, especially the cards related to the five elements of Spirit, Fire, Water, Air and Earth. Crowley wrote a book--The Book of Thoth (Crowley) to accompany, describe, and expand on his deck and the data regarding the pathways within. Unlike the popular Waite-Smith Tarot, the Thoth Tarot retains the traditional order of the trumps but uses alternative nomenclature for both the trumps and of the courts.

Mythic Tarot

The Mythic Tarot deck links Tarot symbolism with the classical Greek Myths.

Hermetic Tarot

Hermetic Tarot utilizes the Tarot archetypes to function as a textbook and mnemonic device for teaching and revealing the gnosis of alchemical symbolical language and its profound and philosophical meanings. An example of this practice is found in the rituals of the 19th Century Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In the 20th Century Hermetic use of the Tarot archetypes as a handbook and revealer of perennial wisdom was further developed in the work of Carl Gustav Jung and his exploration into the psyche and active imagination. A 21st Century example of a Hermetic rooted Tarot deck is that of Tarot ReVisioned, a black and white deck and book for the Major Arcana by Leigh J. McCloskey.[18]

Popular Culture Tarot Decks

The Vertigo Tarot deck employs characters from titles published by Vertigo Comics including such imagery as John Constantine from Hellblazer in the role of The Fool zero card. The cards were illustrated by Dave McKean with text by Rachel Pollack and the accompanying book holds an introduction by Neil Gaiman. In France, where the tarot game is most popular, there have been tarot decks published depicting characters from Asterix, Disney, and Tex Avery cartoons.

Modern oracle cards

Recently, the use of tarot for divination, or as a store of symbolism, has inspired the creation of modern oracle card decks. These are card decks for inspiration or divination containing images of angels, faeries, goddesses, Power Animals, etc. Although obviously influenced by divinatory Tarot, they do not follow the traditional structure of Tarot; they often lack any suits of numbered cards, and the set of cards differs from the conventional major arcana.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. Gerald Duckworth and Company Ltd. ISBN 0-7156-1014-7. Cite error: The named reference "DummettGame" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, ch. 22, "Les Jeux de Gargantua"

- ^ Huson, Paul, (2004) Mystical Origins of the Tarot: From Ancient Roots to Modern Usage, Vermont: Destiny Books, ISBN 0-89281-190-0 Mystical Origins of the Tarot

- ^ Cassandra Eason, Complete Guide to Tarot, p. 3 (Crossing Press, 2000; ISBN 1580910688)

- ^ "History of Tarot Cards". Buzzle.com. July 15 2008. Retrieved January 27 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Harper, Douglas (November 2001). [url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=tarot&searchmode=none "Etymology for Tarot"]. The Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved January 9 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ [url=http://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/tarot "French etymology for tarot"]. Portail Lexical: Lexicographie. Centre National de Ressources Textuelle et Lexicales. 2008. Retrieved January 27 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Donald Laycock in Skeptical—a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0731657942, p. 67

- ^ Banzhaf, Hajo (1994). Il Grande Libro dei Tarocchi (in Italian). Roma: Hermes Edizioni. p. 16. ISBN 8-8793-8047-8.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Michael Dummett: The Game of Tarot, 1980, p. 67

- ^ Place, Robert M. (2005) The Tarot: History,Symbolism,and Divination,, Tarcher/Penguin, New York, ISBN 1-58542-349-1

- ^ CASANOVA, Giacomo. "The Complete Memoires of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt" (HTML). Retrieved January 22nd 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|month=,|accessyear=, and|accessmonthday=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ King, Margareth (1994). The Death of the Child Valerio Marcello. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 341. ISBN 0226436209, 9780226436203.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Berti, Giordano (2002). Visconti Tarot. Lo Scarabeo, Torino.

- ^ Description of the Michelino deck - translated text

- ^ Huson, Paul Mystical Origins of the Tarot: From Ancient Roots to Modern Usage. Vermont: Destiny Books, 2004

- ^ Israel Regardie, "The Tree of Life", (London, Rider, 1932)

- ^ McCloskey, Leigh, Tarot ReVisioned, adpress