Druid: Difference between revisions

m →Romanticism and modern revivals: Move comma to end of independent clause from its middle |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Celtic mythology}} |

{{Celtic mythology}} |

||

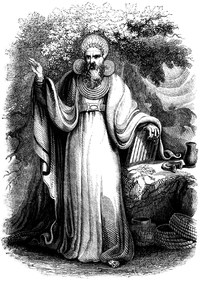

[[Image:Two Druids.PNG|thumb|Two druids, from an 1845 publication, based on a bas-relief found at [[Autun]], France.]] |

[[Image:Two Druids.PNG|thumb|Two druids, from an 1845 publication, based on a bas-relief found at [[Autun]], France.]] |

||

A '''druid''' was a member of the priestly and learned class active in [[Gaul]], and perhaps in [[Celt]]ic culture more generally, during the [[La Tene period|final centuries |

A '''druid''' was a member of the priestly and learned class active in [[Gaul]], and perhaps in [[Celt]]ic culture more generally, during the [[La Tene period|final centuries BC]]. They were suppressed by the [[Ancient Rome|Roman government]] from the 1st century AD and disappeared from the written record by the 2nd century, although there may have been later survivals in [[Great Britain|Britain]] and [[Ireland]]. |

||

Little contemporary evidence about druids exists, and thus little can be said regarding them with assurance. It is known that they held the cultural repository of knowledge in an oral tradition, using poetic verse as a [[mnemonic]] device and to ensure the fidelity of the transmission of knowledge over time. Because of this, most of what is known about them comes from the Roman writers. A common assumption about the druids was that they were just the priests of the Celtic peoples. The reality is that the term encompassed all members of the Celtic learned class, or in [[Dumezil]]'s [[trifunctional hypothesis]], members of the "first function".{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} This would include, for example, bards, judges, scholars, scientists, teachers, sacrificers, seers and priests.<ref>Hutton, Ronald, ''The Druids'' (London: HambledonContinuum, 2007) p2</ref> The core points of druidic religious beliefs reported in Roman sources is their belief in [[reincarnation]], and reverence for the natural world. The same sources report that the Continental Celts in Gaul practised [[human sacrifice]], although current scholars have called this in to question as these sources were probably biased, with Rome being at war with the Celts, and there is little archaeological evidence to support this claim<ref>''"What We Don't Know About the Ancient Celts"'', Rowan Fairgrove, Pomegrante Magazine, Issue 2 1997, retrieved 24 May 2007.[http://www.conjure.com/whocelts.html]</ref> aside from a number of [[bog bodies]]. Their reverence for various aspects of the natural world, such as the [[ritual of oak and mistletoe]] described by [[Pliny the Elder]], has also been associated with [[animism]].<ref name="Mac Mathúna">Mac Mathúna, Liam (1999) [http://www.celt.dias.ie/publications/celtica/c23/c23-174.pdf "Irish Perceptions of the Cosmos"] ''Celtica'' vol. 23 (1999), pp.174-187</ref> |

Little contemporary evidence about druids exists, and thus little can be said regarding them with assurance. It is known that they held the cultural repository of knowledge in an oral tradition, using poetic verse as a [[mnemonic]] device and to ensure the fidelity of the transmission of knowledge over time. Because of this, most of what is known about them comes from the Roman writers. A common assumption about the druids was that they were just the priests of the Celtic peoples. The reality is that the term encompassed all members of the Celtic learned class, or in [[Dumezil]]'s [[trifunctional hypothesis]], members of the "first function".{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} This would include, for example, bards, judges, scholars, scientists, teachers, sacrificers, seers and priests.<ref>Hutton, Ronald, ''The Druids'' (London: HambledonContinuum, 2007) p2</ref> The core points of druidic religious beliefs reported in Roman sources is their belief in [[reincarnation]], and reverence for the natural world. The same sources report that the Continental Celts in Gaul practised [[human sacrifice]], although current scholars have called this in to question as these sources were probably biased, with Rome being at war with the Celts, and there is little archaeological evidence to support this claim<ref>''"What We Don't Know About the Ancient Celts"'', Rowan Fairgrove, Pomegrante Magazine, Issue 2 1997, retrieved 24 May 2007.[http://www.conjure.com/whocelts.html]</ref> aside from a number of [[bog bodies]]. Their reverence for various aspects of the natural world, such as the [[ritual of oak and mistletoe]] described by [[Pliny the Elder]], has also been associated with [[animism]].<ref name="Mac Mathúna">Mac Mathúna, Liam (1999) [http://www.celt.dias.ie/publications/celtica/c23/c23-174.pdf "Irish Perceptions of the Cosmos"] ''Celtica'' vol. 23 (1999), pp.174-187</ref> |

||

The earliest record of the name ''druidae'' ({{lang|grc|Δρυΐδαι}}) is reported from a lost work of the Greek [[doxographer]] [[Sotion]] of Alexandria (early 2nd century |

The earliest record of the name ''druidae'' ({{lang|grc|Δρυΐδαι}}) is reported from a lost work of the Greek [[doxographer]] [[Sotion]] of Alexandria (early 2nd century BC), who was cited by [[Diogenes Laertius]] in the 3rd century AD.<ref>[[Diogenes Laertius]], ''[[Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers]]'' Introduction, Chapters [http://classicpersuasion.org/pw/diogenes/dlintro.htm#1 1] and [http://classicpersuasion.org/pw/diogenes/dlintro.htm#5 5] ([http://www.mikrosapoplous.gr/dl/dl01.html Book A 1 and 6] in the Greek text).</ref> |

||

Modern attempts at reconstructing, reinventing or reimagining the practices of the druids in the wake of [[Celtic revivalism]] are known as [[Neo-druidism]]. |

Modern attempts at reconstructing, reinventing or reimagining the practices of the druids in the wake of [[Celtic revivalism]] are known as [[Neo-druidism]]. |

||

Revision as of 22:28, 6 June 2010

| Part of a series on |

| Celtic mythologies |

|---|

|

A druid was a member of the priestly and learned class active in Gaul, and perhaps in Celtic culture more generally, during the final centuries BC. They were suppressed by the Roman government from the 1st century AD and disappeared from the written record by the 2nd century, although there may have been later survivals in Britain and Ireland.

Little contemporary evidence about druids exists, and thus little can be said regarding them with assurance. It is known that they held the cultural repository of knowledge in an oral tradition, using poetic verse as a mnemonic device and to ensure the fidelity of the transmission of knowledge over time. Because of this, most of what is known about them comes from the Roman writers. A common assumption about the druids was that they were just the priests of the Celtic peoples. The reality is that the term encompassed all members of the Celtic learned class, or in Dumezil's trifunctional hypothesis, members of the "first function".[citation needed] This would include, for example, bards, judges, scholars, scientists, teachers, sacrificers, seers and priests.[1] The core points of druidic religious beliefs reported in Roman sources is their belief in reincarnation, and reverence for the natural world. The same sources report that the Continental Celts in Gaul practised human sacrifice, although current scholars have called this in to question as these sources were probably biased, with Rome being at war with the Celts, and there is little archaeological evidence to support this claim[2] aside from a number of bog bodies. Their reverence for various aspects of the natural world, such as the ritual of oak and mistletoe described by Pliny the Elder, has also been associated with animism.[3]

The earliest record of the name druidae (Δρυΐδαι) is reported from a lost work of the Greek doxographer Sotion of Alexandria (early 2nd century BC), who was cited by Diogenes Laertius in the 3rd century AD.[4]

Modern attempts at reconstructing, reinventing or reimagining the practices of the druids in the wake of Celtic revivalism are known as Neo-druidism.

Etymology

The modern English word druid derives from Latin druides (IPA: [druˈides]).

The native Celtic word for "druid" is first attested in Latin texts as druides (plural)[5][6] and other texts also employ the form druidae, while the same term was used by Greek ethnographers as δρυΐδης (druidēs).[7] It is normally understood that Latin druides is a borrowing from Gaulish.[6][8] Although no extant Romano-Celtic inscription is known to contain the form,[8] the word is cognate with the later insular Celtic words, Old Irish druí ("druid, sorcerer") and early Welsh dryw ("seer").[6] Based on all available forms, the hypothetical proto-Celtic word may then be reconstructed as *dru-wid-s (pl. *druwides) meaning "oak-knower". The two elements go back to the Proto-Indo-European roots *deru-[9] and *weid- "to see".[10] The sense of "oak-knower" (or "oak-seer") is confirmed by Pliny the Elder,[6] who in his Natural History etymologised the term as containing the Greek noun δρύς (drus), "oak-tree"[11] and the Greek suffix -ιδης. The modern Irish word for Oak is Dara, as it derives to anglicised placenames like Derry, and Kildare (literally the "church of oak"). There are many stories and lore about saints, heroes, and oak trees, and also many local stories and superstitions (called pishogues) about trees in general, which still survive in rural Ireland.

Incidentally, both Irish druí and Welsh dryw could also refer to the wren,[6] possibly connected with an association of this bird with augury bird in Irish and Welsh tradition (see also Wren Day).[6][12]

Doctrine

As Ronald Hutton points out, "we can know virtually nothing of certainty about the ancient Druids, so that—although they certainly existed—they function more or less as legendary figures."[13]

Training

Pomponius Mela[14] is the first author who says that the druids' instruction was secret, and was carried on in caves and forests. Druidic lore consisted of a large number of verses learned by heart, and Caesar remarked that it could take up to twenty years to complete the course of study. There is no historic evidence during the period when Druidism was flourishing to suggest that Druids were other than male.[15] What was taught to Druid novices anywhere is conjecture: of the druids' oral literature, not one certifiably ancient verse is known to have survived, even in translation. All instruction was communicated orally, but for ordinary purposes, Caesar reports,[16] the Gauls had a written language in which they used Greek characters. In this he probably draws on earlier writers; by the time of Caesar, Gaulish inscriptions had moved from the Greek script to the Latin script. As a result of this prohibition — and of the decline of Gaulish in favour of Latin — no druidic documents, if there ever were any, have survived.

Ritual and sacrifice

Roman writers regularly discuss the practice of human sacrifice. Gruesome reports of druidic practices appear in Latin histories and poetry, including Lucan, Julius Caesar, Suetonius and Cicero.[17] Human sacrifice was the reason that druidism, unlike other national religions within the empire, was outlawed under Tiberius. The 10th-century Commenta Bernensia expand that sacrifices to Teutates, Esus and Taranis were by drowning, hanging and burning, respectively, taken as a mythologically significant "threefold death" by some proponents of the trifunctional hypothesis.

Diodorus Siculus asserts that a sacrifice acceptable to the Celtic gods had to be attended by a druid, for they were the intermediaries. Diodorus remarks upon the importance of prophets in druidic ritual:

- "These men predict the future by observing the flight and calls of birds and by the sacrifice of holy animals: all orders of society are in their power... and in very important matters they prepare a human victim, plunging a dagger into his chest; by observing the way his limbs convulse as he falls and the gushing of his blood, they are able to read the future."

Diodorus divided the learned classes into bards, soothsayers and druids (whom he said were philosophers and theologians). Strabo echoed this division, labeling them druids (philosophers), bards, and vates (soothsayers). This tripartite division of Celtic priesthood has often been compared to the tripartite Vedic priesthood as reflected in Brahmana literature[citation needed]. The druid as overseer of the sacrifice would correspond to the hotṛ, while the vates as the performer of the actual sacrifice would correspond to the adhvaryu and the bard to the udgātṛ, responsible for liturgy[citation needed].

Archaeological excavations at Ribemont in Picardy, France and at Gournay-sur-Aronde carried out by Jean-Louis Brunaux in the late 1990s were interpreted by Brunaux as human sacrifices, but the British archaeologist Martin Brown has suggested that these might be war memorials honouring the dead for their courage.[18] At a bog in Lindow, Cheshire, England was discovered a body, designated the "Lindow Man", which may also have been the victim of a druidic ritual, but it is just as likely that he was an executed criminal or a victim of violent crime.[19] The body is now on display at the British Museum, London. In Ireland similar discoveries in 2003 of two murdered individuals preserved in separate bogs, each subsequently dated to around 100 BCE, lends some credence to the ritual murder theory.[20]

Philosophy

Alexander Cornelius Polyhistor referred to the Druids as philosophers and called their doctrine of the immortality of the soul and reincarnation or metempsychosis "Pythagorean":

- "The Pythagorean doctrine prevails among the Gauls' teaching that the souls of men are immortal, and that after a fixed number of years they will enter into another body."

"The principal point of their doctrine", says Caesar, "is that the soul does not die and that after death it passes from one body into another" (see metempsychosis). Caesar wrote:

"With regard to their actual course of studies, the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed. Subsidiary to the teachings of this main principle, they hold various lectures and discussions on astronomy, on the extent and geographical distribution of the globe, on the different branches of natural philosophy, and on many problems connected with religion".

— Julius Caesar, "De Bello Gallico", VI, 13

This led Diodorus Siculus and others to the unlikely conclusion that the druids may have been influenced by the teachings of Pythagoras,[21] One modern scholar has speculated that Buddhist missionaries had been sent by the Indian king Ashoka.[22] Others have invoked common Indo-European parallels.[23]

Role in Gallic society

Caesar notes that all men of any rank and dignity in Gaul were included either among the druids or among the nobles (equites), indicating that they formed two classes. The druids constituted the learned priestly class (disciplina), and were guardians of the unwritten, ancient customary law. This gave druids the authority to execute judgments on criminals, among which exclusion from society was the most dreaded. Druids were not a hereditary caste, though they enjoyed exemption from military service as well as from payment of taxes. The course of training to which a novice had to submit was protracted.

Writers such as Diodorus Siculus and Strabo wrote about the role of druids in Gallic society. Both Diodorus and Strabo reported that Druids were held in such respect that if they intervened between two armies they could stop the battle.[24] Strabo reports druids still acting as arbiters in public and private matters, but they note that by that time they no longer dealt with cases of murder. Strabo suggests that druids were "the most just of men."[25]

Caesar noted the druidic doctrine of the original ancestor of the tribe, whom he referred to as Dispater, or Father Hades. Caesar also reported that druids could punish members of Celtic society by a form of excommunication, preventing them from attending religious festivals.[26]

History

Early records

There is no evidence of druids predating the 2nd century BCE. Greek and Roman writers on the Celts commonly made at least passing reference to druids, though before Caesar's report, they were referred to merely as "barbarian philosophers".[27] These writers were not concerned with ethnology or comparative religion,[28] and consequently our historical knowledge of druids is very limited.

Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, book VI, published in the 50s or 40s BCE, gives the first surviving[29] and the fullest account of the druids, whom, in an apparent contradiction to the social importance he alleges for them, he has scarcely any occasion to mention elsewhere,[30] though Caesar is generally at pains to explain political situations that affected the progress of his narrative.[31] His single excursus on druids is based in part on Eratosthenes and other Greeks.[32]

Many historians argue[33] that Caesar's description of the role of druids in Gaulish society may report an idealised tradition, based on the society of the 2nd Century BCE, before the pan-Gallic confederation led by the Arverni was smashed in 121 BCE, followed by the invasions of Teutones and Cimbri, rather than on the demoralised and disunited Gaul of his own time, Norman J. DeWitt surmised.[34] John Creighton has speculated that in Britain, the druidic social influence was already in decline by the mid-first century BCE, in conflict with emergent new power structures embodied in paramount chieftains.[35] Others, meanwhile,[36] find the decline in the context of Roman conquest itself.

Other historians argue[37] that despite Caesar's execution of Dumnorix, his problem dealt with anti-Romans and not just druids. Historically speaking, the brother of Dumnorix, Diviciacus, was a good friend to Cicero and Rome. Diviciacus was the only specifically identified individual druid in any classical literary source. Cicero remarks on the existence among the Gauls of augurs or soothsayers, known by the name of druids; he had made the acquaintance of one Diviciacus, an Aeduan also known to Caesar.[38]

Prohibition and decline under Roman rule

Druids were seen as essentially non-Roman: a rescript of Augustus forbade Roman citizens to practice "druidical" rites. Under Tiberius, Pliny reported,[39] the druids were suppressed—along with diviners and physicians— by a decree of the Senate, but this had to be renewed by Claudius in 54 CE.

Tacitus, in describing the attack made on the island of Mona (Anglesey, Ynys Môn in Welsh) by the Romans under Suetonius Paulinus, represents the legionaries as being awestruck on landing by the appearance of a band of druids, who, with hands uplifted to the sky, poured forth terrible imprecations on the heads of the invaders. He states that these "terrified our soldiers who had never seen such a thing before..." The courage of the Romans, however, soon overcame such fears, according to the Roman historian; the Britons were put to flight, and the sacred groves of Mona were cut down (Annals 14.30).

Tacitus is also the only primary source that gives accounts of Druidism in Britain, but maintains a hostile point of view. Druids in the eyes of Tacitus were seen as ignorant savages[40] who "deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails." Professor Ronald Hutton points out that there "is no evidence that Tacitus ever used eye-witness reports" and casts doubt upon the reliability of Tacitus's report.[41]

After the first century CE the continental druids disappeared entirely and were referred to only on very rare occasions. Ausonius, for one instance, apostrophizes the rhetorician Attius Patera as sprung from a "race of druids".

Phillip Freeman, a classics professor, discusses a later reference to Dryades, which he translates as Druidesses, writing that "The fourth century A.D. collection of imperial biographies known as the Historia Augusta contains three short passages involving Gaulish women called "Dryades" ("Druidesses")." He points out that "In all of these, the women may not be direct heirs of the Druids who were supposedly extinguished by the Romans — but in any case they do show that the druidic function of prophesy continued among the natives in Roman Gaul."[42] However, the Historia Augusta is frequently interpreted by scholars as a largely satirical work, and such details might have been introduced in a humorous fashion. Additionally, Druidesses are mentioned in later Irish mythology, including the legend of Fionn mac Cumhaill, who, according to the 12th century The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn, is raised by the druidess Bodhmall and a wise-woman.[43][44]

Possible late survival of Insular druidism

The best evidence of a druidic tradition in the British Isles is the independent cognate of the Celtic *druwid- in Insular Celtic: The Old Irish draoiocht survives in the meaning of "magic", and the Welsh dryw in the meaning of "seer". Although there are no contemporary records of Insular druidism in antiquity other than the account by Tacitus, there is some evidence that the druidic tradition in Ireland may have survived until as late as the 7th century: in the De Mirabilibus Sacrae Scripturae of Augustinus Hibernicus (f. 655), there is mention of local magi who teach a doctrine of reincarnation in the form of birds. The word magus was often used in Hiberno-Latin works for a translation of druid.[45]

While the druids as a priestly caste were extinct with the Christianization of Wales, complete by the 7th century at the latest, the offices of bard and of "seer" (Welsh: dryw) persisted in medieval Wales into the 13th century.

Archaeological evidence

Druidic associations with the ritual deaths of some of the bog bodies recovered in the British Isles and northern Europe from the Netherlands to Denmark, presented by Anne Ross[46] is resisted by some historians, such as Jane Webster, who asserted in 1999, "individual druids (let alone druid princes) are unlikely to be identified archaeologically"[47] A.P. Fitzpatrick, in examining astral symbolism on Late Iron Age swords[48] has expressed difficulties in relating any material culture, even the Coligny calendar, with druidic culture. Slain bodies as far east as Celtic Galatia and elsewhere in Northern and Western Europe are widely cited as evidence of human sacrifice.[49]

Legacy and reception

Welsh dryw

Dryw is a term for "seer" in Welsh mythology, comparable to Irish fáith. Etymologically, the term is connected to the name of the druids, while fáith derives from that of the vates, both denoting classes of priests in Celtic antiquity, and for this reason the term is often also translated as "druid" even in the medieval Welsh context.[50] Dryw is also the Welsh name of the wren, which has been taken as an indication of a connection of the medieval Welsh seers and auspices involving these birds.

The Buarth Beirdd, a poem ascribed to the 6th-century bard Taliesin and preserved in the early 14th-century manuscript known as Book of Taliesin, includes the verse:

- Wyf dur wyf dryw wyf saer wyf syw (BT 7.18)

- "I am a tower; I am a seer; I am a craftsman; I am a scholar."[51]

Another poem in the book has the verse

- Dwfyn darogan dewin drywon

- "deep is the prophecy divine of the seers".[52]

The offices of bardd and of dryw "seer" persist in medieval Wales into the 13th century and possibly as late as the time of Owain Glyndŵr (d. 1416). Purges of bards during the Welsh campaigns of Edward I supposedly culminated with the legendary suicide of The Last Bard (c.1283). One of the last entries in the Annals of Owain Glyndwr makes a final reference to "seers".[53]

Early Irish law and literature

When druids are portrayed in early Irish sagas and saints' lives set in the pre-Christian past of the island, they are usually accorded high social status. The evidence of the law-texts, which were first written down in the seventh and eighth centuries, suggests that with the coming of Christianity the role of the druid (Old Irish druí) in Irish society was rapidly reduced to that of a sorcerer who could be consulted to cast spells or practise healing magic and that his standing declined accordingly.[54] According to the early legal tract Bretha Crólige, the sick-maintenance due to a druid, satirist and brigand (díberg) is no more than that due to a bóaire (an ordinary freeman). Another law-text, Uraicecht Becc (‘Small primer’), gives the druid a place among the dóer-nemed or professional classes which depend for their status on a patron, along with wrights, blacksmiths and entertainers, as opposed to the fili, who alone enjoyed free nemed-status.[55]

The most important documents of Old Irish literature are contained in manuscripts of the 12th century or later, but many of the texts themselves date back to as early as the 8th century. In these stories, druids usually act as advisers to kings. They were said to have the ability to foretell the future (Bec mac Dé, for example, predicted the death of Diarmait mac Cerbaill more accurately than three Christian saints) and there is little reference to their religious function. They do not appear to form any corporation, nor do they seem to be exempt from military service.

In the Ulster Cycle, Cathbad, chief druid at the court of Conchobar, king of Ulster, is accompanied by a number of youths (100 according to the oldest version) who are desirous of learning his art. Cathbad is present at the birth of the famous tragic heroine Deirdre, and prophesies what sort of a woman she will be, and the strife that will accompany her, although Conchobar ignores him. The following description of the band of Cathbad's druids occurs in the epic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge: The attendant raises his eyes towards the heavens and observes the clouds and answers the band around him. They all raise their eyes towards the heavens, observe the clouds, and hurl spells against the elements, so that they arouse strife amongst them and clouds of fire are driven towards the camp of the men of Ireland. We are further told that at the court of Conchobar no one had the right to speak before the druids had spoken.

Also in the Táin Bó Cúailnge, before setting out on her great expedition against Ulster, Medb, queen of Connacht, consults her druids regarding the outcome of the war. They hold up the march by two weeks, waiting for an auspicious omen. Druids were also said to have magical skills: when the hero Cúchulainn returned from the Other World, after having been enticed there by a fairy woman or goddess, named Fand, whom he is now unable to forget, he is given a potion by some druids, which banishes all memory of his recent adventures and which also rids his wife Emer of the pangs of jealousy.

More remarkable still is the story of Étaín. This lady, later the wife of Eochaid Airem, High King of Ireland, was in a former existence the beloved of the god Midir, who again seeks her love and carries her off. The king has recourse to his druid, Dalgn, who requires a whole year to discover the haunt of the couple. This he accomplished by means of four wands of yew inscribed with ogham characters.

In other texts the druids are able to produce insanity. Mug Ruith, a legendary druid of Munster, wore a hornless bull's hide and an elaborate feathered headdress and had the ability to fly and conjure storms.

Christian historiography and hagiography

The story of Vortigern, as reported by Nennius, provides one of the very few glimpses of druidic survival in Britain after the Roman conquest: unfortunately, Nennius is noted for mixing fact and legend in such a way that it is now impossible to know the truth behind his text. For what it is worth, he asserts that, after being excommunicated by Germanus, the British leader Vortigern invited twelve druids to assist him.

In the lives of saints and martyrs, the druids are represented as magicians and diviners. In Adamnan's vita of Columba, two of them act as tutors to the daughters of Lóegaire mac Néill, the High King of Ireland, at the coming of Saint Patrick. They are represented as endeavouring to prevent the progress of Patrick and Saint Columba by raising clouds and mist. Before the battle of Culdremne (561) a druid made an airbe drtiad (fence of protection?) round one of the armies, but what is precisely meant by the phrase is unclear. The Irish druids seem to have had a peculiar tonsure. The word druí is always used to render the Latin magus, and in one passage St Columba speaks of Christ as his druid. Similarly, a life of St Beuno states that when he died he had a vision of 'all the saints and druids'.

Sulpicius Severus' Vita of Martin of Tours relates how Martin encountered a peasant funeral, carrying the body in a winding sheet, which Martin mistook for some druidic rites of sacrifice, "because it was the custom of the Gallic rustics in their wretched folly to carry about through the fields the images of demons veiled with a white covering." So Martin halted the procession by raising his pectoral cross: "Upon this, the miserable creatures might have been seen at first to become stiff like rocks. Next, as they endeavored, with every possible effort, to move forward, but were not able to take a step farther, they began to whirl themselves about in the most ridiculous fashion, until, not able any longer to sustain the weight, they set down the dead body." Then discovering his error, Martin raised his hand again to let them proceed: "Thus," the hagiographer points out," he both compelled them to stand when he pleased, and permitted them to depart when he thought good."[56]

Romanticism and modern revivals

From the 18th century, England and Wales experienced a revival of interest in the druids. John Aubrey (1626–1697) had been the first modern writer to connect Stonehenge and other megalithic monuments with the druids; since Aubrey's views were confined to his notebooks, the first wide audience for this idea were readers of William Stukeley (1687–1765).[57] John Toland (1670–1722) shaped ideas about the druids current during much of the 18th and 19th centuries. He founded the Ancient Druid Order in London which existed from 1717 until it split into two groups in 1964. The order never used ( and still does not use ) the title "Archdruid" for any member, but in retrospect credited William Blake as having been its "Chosen Chief" from 1799 to 1827, without corroboration in Blake's numerous writings or among modern Blake scholars. Blake's bardic mysticism derives instead from the pseudo-Ossianic epics of Macpherson; his friend Frederick Tatham's depiction of Blake's imagination, "clothing itself in the dark stole of mural sanctity"— in the precincts of Westminster Abbey— "it dwelt amid the Druid terrors", is generic rather than specifically neo-Druidic.[58] John Toland was fascinated by Aubrey's Stonehenge theories, and wrote his own book about the monument without crediting Aubrey.

The nineteenth-century idea, gained from uncritical reading of the Gallic Wars, that under cultural-military pressure from Rome the druids formed the core of first-century BCE resistance among the Gauls, was examined and dismissed before World War II,[59] though it remains current in folk history.

Druids began to figure widely in popular culture with the first advent of Romanticism. Chateaubriand's novel Les Martyrs (1809) narrated the doomed love of a druid priestess and a Roman soldier; though Chateaubriand's theme was the triumph of Christianity over Pagan druids, the setting was to continue to bear fruit. Opera provides a barometer of well-informed popular European culture in the early 19th century: in 1817 Giovanni Pacini brought druids to the stage in Trieste with an opera to a libretto by Felice Romani about a druid priestess, La Sacerdotessa d'Irminsul ("The Priestess of Irminsul"). The most famous druidic opera, Vincenzo Bellini's Norma was a fiasco at La Scala, when it premiered the day after Christmas, 1831; but in 1833 it was a hit in London. For its libretto, Felice Romani reused some of the pseudo-druidical background of La Sacerdotessa to provide colour to a standard theatrical conflict of love and duty. The story was similar to that of Medea, as it had recently been recast for a popular Parisian play by Alexandre Soumet: the diva of Norma's hit aria, "Casta Diva", is the moon goddess, being worshipped in the "grove of the Irmin statue".

A central figure in 19th century Romanticist Neo-Druidism is the Welshman Edward Williams, better known as Iolo Morganwg. His writings, published posthumously as The Iolo Manuscripts (1849) and Barddas (1862), are not considered credible by contemporary scholars. Williams claimed to have collected ancient knowledge in a "Gorsedd of Bards of the Isles of Britain" he had organized. Many scholars deem part or all of Williams's work to be fabrication, and purportedly many of the documents are of his own fabrication, but a large portion of the work has indeed been collected from meso-pagan sources dating from as far back as 600 A.D.[citation needed] Regardless, it has become impossible to separate the original source material from the fabricated work, and while bits and pieces of the Barddas still turn up in some "Neo-druidic" works, the documents are considered irrelevant by most serious scholars.

T.D. Kendrick's dispelled (1927) the pseudo-historical aura that had accrued to druids,[60] asserting that "a prodigious amount of rubbish has been written about druidism";[61] Neo-druidism has nevertheless continued to shape public perceptions of the historical druids. The British Museumis blunt:

Modern Druids have no direct connection to the Druids of the Iron Age. Many of our popular ideas about the Druids are based on the misunderstandings and misconceptions of scholars 200 years ago. These ideas have been superseded by later study and discoveries.[62]

Some strands of contemporary Neodruidism are a continuation of the 18th-century revival and thus are built largely around writings produced in the 18th century and after by second-hand sources and theorists. Some are monotheistic. Others, such as the largest Druid group in the world, The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids draw on a wide range of sources for their teachings. Members of such Neo-druid groups may be Neopagan, occultist, Reconstructionist, Christian or non-specifically spiritual.

References

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: HambledonContinuum, 2007) p2

- ^ "What We Don't Know About the Ancient Celts", Rowan Fairgrove, Pomegrante Magazine, Issue 2 1997, retrieved 24 May 2007.[1]

- ^ Mac Mathúna, Liam (1999) "Irish Perceptions of the Cosmos" Celtica vol. 23 (1999), pp.174-187

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers Introduction, Chapters 1 and 5 (Book A 1 and 6 in the Greek text).

- ^ Druides, Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, on Perseus project

- ^ a b c d e f Caroline aan de Wiel, "druids [3] the word", in Celtic Culture.

- ^ Pokorny's Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, see also American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.), Δρυίδης

- ^ a b Piggot, The Druids, p. 89.

- ^ Proto-IE *deru-, a cognate to English tree, is the word for "oak", though the root has a wider array of meanings related to "to be firm, solid, steadfast" (whence e.g. English true). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Fourth Edition, 2000 Indo-European Roots: deru-.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition, 2000 Indo-European Roots: weid-.

- ^ δρῦς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ^ See further Brian Ó Cuív, "Some Gaelic traditions about the wren". Éigse 18 (1980): pp. 43-66.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007) p. xii

- ^ Pomponius Mela iii.2.18-19.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (1993). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. ISBN 0-631-18946-7 p.171

- ^ Gallic Wars vi.14.3.

- ^ Lucan, Pharsalia i.450-58; Caesar, Gallic Wars vi.16, 17.3-5; Suetonius, Claudius 25; Cicero, Pro Font. 31; Cicero, De Rep. 9 (15);cited after Norman J. DeWitt, "The Druids and Romanization" Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 69 (1938:319-332) p 321 note 4

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007 pp.133-134

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007 pp.132

- ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/01/0117_060117_irish_bogmen.html

- ^ Diodorius Siculus v.28.6; Hippolytus Philosophumena i.25.

- ^ Donald A.Mackenzie, Buddhism in pre-Christian Britain (1928:21).

- ^ Isaac Bonewits, Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism, Citadel, 2006.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007 p44–45

- ^ Rutherford, Ward The Druids and their Heritage pg 78

- ^ Caesar, Gaius Iulius, Commentarii de Bello Gallico Book VI

- ^ Twenty references were presented in tabular form by Jane Webster, "At the End of the World: Druidic and Other Revitalization Movements in Post-Conquest Gaul and Britain" Britannia 30 (1999:1-20):2-4; they ran from the lost Magikos of Sotion of Alexandria, cited as by Aristotle (died 332 BCE) in Diogenes Laertius' vita, to Ausonius in the fourth century CE.

- ^ Stuart Piggott, examining the folklore connection of "The Druids and Stonehenge" in The South African Archaeological Bulletin 9 No. 36 (December 1954:138-140) saw the Greek viewpoint "rather as a colonial administrator sixty or seventy years ago might have recorded a few of the more startling facts about the witch-doctors or medicine men he had heard of or encountered on Africa or the Orient." (p. 138).

- ^ The ethnographic account in a continuation of Polybius' history of Rome written by the Stoic scholar Posidonius, on which Caesar and other writers seem to have depended, is lost; see Daphne Nash, "Reconstructing Poseidonios' Celtic Ethnography: Some Considerations", Britannia 1976:111-26. Posidonius' consideration of Gaulish society was presented in book xxiii of his History, as the backdrop for the First Transalpine War, against the Celtic Ligurians of the Maritime Alps, 125–21 BCE.

- ^ Not even Diviacus is mentioned by Caesar as a druid.

- ^ A point made, in noting the discrepancy, by Norman J. DeWitt, "The Druids and Romanization" Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 69 (1938:322f).

- ^ Caesar, Gallic Wars vi.24.2.

- ^ See, e.g. Jane Webster 1999:6-8 "Caesar's Druids: an anachronism?"

- ^ DeWitt 1938:324f.

- ^ Creighton, "Visions of power: imagery and symbols in Late Iron Age Britain" Britannia 26 (1995:285-301) especially p 296f.

- ^ e.g. Jane Webster, in "At the End of the World: Druidic and Other Revitalization Movements in Post-Conquest Gaul and Britain" Britannia 30 (1999:1-20 and full bibliography).

- ^ Dewitt, Norman The Druids and Romanization, p. 323

- ^ Cicero, De Divinatione 1.41

- ^ Pliny's Natural History xxx.4.

- ^ Rutherford, Ward The Druids and their Heritage' pg 45

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Druids (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007 pp.3-5

- ^ Freeman, Phillip,War, Women & Druids: Eyewitness Reports and Early Accounts, University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0292725454 pp. 49-50

- ^ Jones, Mary. "The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn mac Cumhaill". From maryjones.us. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Parkes, "Fosterage, Kinship, & Legend", Cambridge University Press, Comparative Studies in Society and History (2004), 46: 587-615

- ^ Augustinus Hibernicus. "De Mirabilibus Sacrae Scripturae". King of Mysteries: Early Irish Religious Writings edited by John Carey. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000.

- ^ Anne Ross, "Lindow Man and the Celtic tradition", in I.M. Stead, J.B. Bourke and D. Brothwell, Lindow Man; The Body in the Bog, 1986:162-69; Anne Ross and Don Robins, The Life and Death of a Druid Prince 1989.

- ^ Webster 1999:6.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, "Night and Day: the symbolism of astral signs on Late Iron Age anthropomorphic short swords", Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 62 pp 373-98.1996:

- ^ Freeman, Philip The Philosopher and the Druids p. 161 2006 Simon and Schuster

- ^ J. Roberts, Druidical remains and antiquities of the ancient Britons, principally in Glamorgan: containing a general account of the same, in England, Wales, Scotland, France, &c.; with notes and illustrations on the learning, origin, and superstition of the druids, the downfall of druidism as a religious system, and the introduction of Christianity into Britain, printed by E. Griffiths (1842).[2]

- ^ Buarch Beird, written Buarch Beird in the MS.

- ^ William Forbes Skene, The four ancient books of Wales containing the Cymric poems attributed to the bards of the sixth century, Edmonston and Douglas, 1868, p. 211f.[3]

- ^ "1415. Owain went into hiding on Saint Matthew's Day in Harvest, and thereafter his hiding place was unknown. Very many said that he died; the seers maintain he did not." (trans. John Edward Lloyd, 1931).

- ^ Kelly, A Guide to Early Irish Law, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Kelly, A Guide to Early Irish Law, p. 60.

- ^ Hagiography.

- ^ The modern career of this imagined connection of druids and Stonehenge was traced and dispelled in T.D. Kendrick, The Druids: A Study in Keltic Prehistory (London: Methuen) 1927.

- ^ Tatham is quoted by C. H. Collins Baker, "William Blake, Painter", The Huntington Library Bulletin, No. 10 [October 1936:135-148] p. 139.

- ^ Norman J. DeWitt, "The Druids and Romanization" Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 69 (1938:319-332): "Few historians now believe that the Druids, as a corporation, constituted an effective anti-Roman element during the period of Caesar's conquests and in the period of early Roman Gaul;" his inspection of the seemingly contradictory literary sources reinforced the stated conclusion.

- ^ T.D. Kendrick, The Druids: A Study in Keltic Prehistory (London: Methuen) 1927.

- ^ Kendrick 1927:viii

- ^ "Explore/". The British Museum. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Secondary sources

- Kelly, Fergus (1988). A Guide to Early Irish Law. Early Irish Law Series 3. Dublin: DIAS. ISBN 0901282952.

- Wiel, Caroline aan de. "druids [3] the word." In Celtic Culture. A Historical Encyclopaedia, ed. John T. Koch. 2006. pp. 615–6.

Further reading

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda J., Exploring the World of the Druids (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997)

- Ellis, Peter, B., "The Druids" (William B. Eerdmans, 1994)

- Fitzpatrick, A. P,. Who were the Druids? (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1997)

- Hutton, Ronald, The Druids: A History (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2008)

- Hutton, Ronald, Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain (Yale University Press, 2009)

- Piggott, Stuart, The Druids (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)