LGBTQ movements in the United States: Difference between revisions

m →Anti-transgender hate crimes: corrected group name and founders' attribution |

|||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

===Anti-transgender hate crimes=== |

===Anti-transgender hate crimes=== |

||

Transexual Menace, co-founded by [[Riki Wilchins]] and [[Denise Norris]] in 1994, the year that Transgender Nation folded, tapped into and provided an outlet for the outrage many transgender people experienced in the brutal murder of [[Brandon Teena]], a transgender youth, and two of his friends in a farmhouse in rural [[Nebraska]] on December 31, 1993. The murders, depicted in [[Kimberly Peirce]]'s Academy Award-winning feature film ''[[Boys Don't Cry (film)|Boys Don't Cry]]'' (2000), called dramatic attention to the serious, on-going problem of anti-transgender violence and hate crimes. |

|||

The website Remembering Our Dead, compiled by activist Gwen Smith and hosted by the [[Gender Education Association]], honors the memory of the transgender murder victims—roughly one person a month. The Remembering Our Dead project spawned the National Day of Remembrance, an annual event begun in 1999, which is now observed in dozens of cities around the world. |

The website Remembering Our Dead, compiled by activist Gwen Smith and hosted by the [[Gender Education Association]], honors the memory of the transgender murder victims—roughly one person a month. The Remembering Our Dead project spawned the National Day of Remembrance, an annual event begun in 1999, which is now observed in dozens of cities around the world. |

||

Revision as of 21:58, 11 January 2011

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender ∙ Queer |

|

|

LGBT movements in the United States comprise an interwoven history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender social and political movements in the United States of America, beginning in the early 20th century. They have been influential worldwide in achieving social progress for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered and transsexual people.

Daughters of Bilitis

The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), was the first lesbian rights organization in the U.S. It was formed in San Francisco, California in 1955 by four lesbian couples, including Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin who began meeting with other female couples to create a social alternative to lesbian bars, which were considered illegal and thus subject to raids and police harassment. The DOB followed the model of the homophile movement as developed by the Mattachine Society by encouraging its members to assimilate as much as possible into the prevailing heterosexual culture. The DOB advertised itself as "A Woman's Organization for the purpose of Promoting the Integration of the Homosexual into Society."

As the DOB gained members, their focus shifted to providing support to women who were afraid to come out by educating them about their rights and their history. When the club realized they weren't allowed to advertise their meetings in the newspaper, Lyon and Martin began to print the group's newsletter, The Ladder, in October 1956. It became the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the U.S. and was distributed to a closely guarded list of subscribers, a list DOB organizers feared could incriminate its readers if obtained by police or FBI investigators. Barbara Gittings was editor for The Ladder from 1963 to 1968 when she passed her editorship to Barbara Grier, who greatly expanded it, until the publication met its end in 1972 due to lack of funding.

By 1959 there were chapters of the DOB in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Rhode Island along with the original chapter in San Francisco. In 1969, Grier reported of an Australia chapter as well as attempts to form chapters in New Zealand and Scandinavia. The group also held conferences every two years from 1960 to 1968. The DOB lasted for fourteen years and became a tool of education for lesbians, gay men, researchers, and mental health professionals. As a national organization, the DOB folded in 1970, although some local chapters still continue.

Martin and Lyon also have the distinction of being the first legally married gay couple in the U.S. at the start of the historic San Francisco 2004 same-sex weddings.[1] Their marriage was voided 6 months later by the California Supreme Court.

Mattachine Society

The Mattachine Society was perhaps one of the earliest and influential American gay movement groups. Formed in Los Angeles in 1950 as the International Bachelors Fraternal Order for Peace and Social Dignity, by William Dale Jennings, along with seven other gay men, it rapidly began to influence gay society and politics. It later adopted the name The Mattachine Society in reference to the society Mattachine, a French medieval masque group that supposedly traveled broadly using entertainment to point out social injustice. The name symbolized the fact that gays were a masked people, who lived in anonymity.

The Mattachine founders attempted to use their personal experience as gay men to redefine the meaning of gay people and their culture in the United States and set goals for cultural and political liberation.

In 1951, the Society adopted a Statement of Missions and Purpose. This statement stands out today in the history of the gay liberation movement by identifying two important themes. First, it called for a grassroots movement of gay people to challenge anti-gay discrimination, and second, it recognized the importance of building a gay community.

The society also began sponsoring discussion groups in 1951, which provided Lesbian and gay men an ability to openly share feelings and experiences. For many, this was the first opportunity to do so, and such meetings were often highly emotional affairs. Attendance at the Mattachine Society meetings dramatically increased over the next few years, and such discussion groups spread throughout the United States, even beginning to sponsor social events, write newsletters and publications, and hold fundraisers.

A group within the Mattachine Society, ONE, incorporated and produced ONE magazine. It was independent from the Society, but its first editor and most of its editorial board were members of the society. The Los Angeles Postmaster seized and refused to mail copies of ONE Magazine in 1954 on grounds that it was "obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy." This action led to prolonged court battles which had significant influence on gay and lesbian movements. In 1958, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled unanimously in One, Inc. v. Olesen that the mere discussion of homosexuality was not obscene, and the magazine continued to be published and distributed until 1972.

The Society became highly active in protesting police entrapment and oppressive tactics and policies toward gay men.

Because of the communist leanings of some of the Society's members, particularly its primary founder, and its political actions, the society was forced to endure heavy pressure and public scrutiny during the anti-communist McCarthyism period. In a column of the Los Angeles newspaper in March 1953 in regards to the Society, it was called a "strange new pressure group" of "sexual deviants" and "security risks" who were banding together to wield "tremendous political power."

This article created a panic among society members and resulted in public meetings of gay people. These were attended by delegates representing hundreds of discussion group participants. A strong coalition of conservative delegates emerged that challenged the societies goals, even the idea that gay people were a legitimate minority group, because they thought such things would encourage hostility among the mainstream public. The Society board members disagreed, but fearing consequences of government investigation of society activities, the original founders resigned in 1953, and the organization was turned over to the conservative elements who began a restructure of it.

The former goals were revised. Rather than social change, they advocated accommodation, and rather than mobilizing gay people, they sought the support of the psychiatric profession who they believed held the key to reform. This, however, had a devastating effect as discussion group attendance declined and many local chapters folded. The national structure was dissolved in 1961, and even the New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco chapters remained active for only a few more years. The societies' political and social influence continued to decrease after the Los Angeles News article.

Other organizations used the name "Mattachine" that were not formally associated with the original Mattachine Society or its national structure. For example, Chicago’s Mattachine Midwest, established in 1965 was a completely independent organization. Other organizations such as the San Francisco Society for individual Rights, Gay Liberation Front, and Gay Activists Alliance became dominant in the gay liberation movement after Mattachine declined. Because of its failure to adapt to the increasing militancy of gay men and lesbians, the Mattachine faded away after the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969.

ONE, Incorporated

ONE, Inc. was started by William Dale Jennings joined with Don Slater, Dorr Legg, Tony Reyes, and Mattachine Society founder Harry Hayes. It formed the public part of the early homophile movement, with a public office, public meetings, a telephone, and the first publication that reached the general public, ONE Magazine.

Later, part of ONE became the Homosexual Information Center, formed by Don Slater, Billy Glover, Joe and Jane Hansen, Tony Reyes, Jim Schneider, et al. Part of ONE's archives are at USC and part at CSUN. The funding part of ONE still exists as the Institute for the Study of Human Resources, which controls the name ONE, Inc.

Websites for parts of ONE and HIC are:

Student rights movements

Although students attracted to others of the same sex had developed semi-private meeting places and informal social networks at many colleges and universities since at least the early 20th century, the first formally recognized gay student organizations were not established until the late 1960s. But the success of these early groups, along with the inspiration provided by other college-based movements and the Stonewall riots, led to the proliferation of Gay Liberation Fronts on campuses across the country by the early 1970s.

At many colleges and universities, these organizations were male-dominated, prompting lesbians to demand greater inclusion and often to form their own groups. In the 1980s and 1990s, bisexual and transgender students likewise sought recognition, both within and separate from lesbian and gay organizations. At the same time, high school and junior high school students have begun to organize Gay-Straight Alliances, enabling even younger glbtq people to find support and better advocate for their needs.

Early student groups

The Student Homophile League was the first student gay rights organization in the United States, established at Columbia University in 1967. Its founder, Stephen Donaldson, was a former member of the New York City chapter of the Mattachine Society. He established the Student Homophile League because was forced by school administration to move out of his residence hall after complaints from roommates about living with a homosexual man. When Donaldson began meeting other GLBTQ students, he suggested they form a Mattachine-like organization on campus, and envisioned it as the first in a national coalition of student gay rights groups.

With his assistance, Student Homophile League branches were chartered at Cornell University and New York University in 1968 and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the Spring of 1969. This led to the formation of two non-affiliated groups, the Homosexuals Intransigent at the City University of New York and FREE (Fight Repression of Erotic Expression) at the University of Minnesota in 1969, now the Queer Student Cultural Center.

These first student organizations provided support to individuals who questioned their sexuality. They passed out gay rights literature, held dances and other social events, and sponsored lectures about the gay experience. Through their efforts, the campus climate for GLBTQ people improved, and made it possible for many others to actually accept themselves and come out. Also, by gaining institutional recognition and establishing a place on campus for GLBTQ students, the groundwork was laid for the creation of GLBTQ groups at colleges and universities throughout the country. By 1971, such groups had surfaced at more than 175 educational institutions across the United States.

Gay liberation fronts

Although the pre-Stonewall student Homophile Leagues were most heavily influenced by the Mattachine Society, the Post Stonewall student organizations were more likely to be inspired and named after the more militant Gay Liberation Front or (GLF). It was formed in New York City in summer of 1969, and in Los Angeles by activist Morris Kight the same year.

GLF-like campus groups held sponsored social activities, educational programs, and provided support to individual members much like the earlier college groups. However, activists in the GLF-type groups generally were much more visible and more politically oriented than the pre-stonewall gay student groups. These new activists were often committed to radical social change, and preferred confrontational tactics such as demonstrations, sit-ins, and direct challenges to discriminatory campus policies. This new defiant philosophy and approach was influenced by other militant campus movements such as Black Power, anti-Vietnam war groups, and student free speech movements. Many GLF members were involved with other militant groups such as these, and saw gay rights as part of a larger movement to transform society; their own liberation was fundamentally tied to the liberation of all peoples.

Lesbian feminist groups

Despite the fact that most of these early groups stated themselves to support women’s liberation, many of the gay student groups were dominated by men. In fact, activities were more aimed at the needs of gay men, even to the point of exclusion to the needs of lesbians and bisexual women. This extended to frequently directing attention to campus harassment of gay men while ignoring the concerns and needs of gay women. Gay women were frequently turned off by the focus on male cruising at many of these events, and as a result, lesbians and bisexual women on some campuses began to hold their own dances and social activities.

As gay began to increasingly refer only to gay men in the 1970s, many lesbians sought to have the names of gay student organizations changed to include them explicitly, or formed their own groups. They saw a need to organize around their oppression as women as well as lesbians, since they knew they could never have an equal voice in groups where men held the political power.

Gay Liberation Front

When the police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village in New York City in June 1969, an unprecedented riot broke out among the patrons. Throughout the weekend, gay men and lesbians came to the Stonewall to protest the police and their abusive tactics.

This event served as a catalyst for the emergence of a new breed of gay militant activists quite unlike the more conventional organizations of the past two decades, and became known as gay liberation. Within weeks of the Stonewall event, gay and lesbian activists organized the Gay Liberation Front, using much of what had been built upon by the earlier groups. The GLF saw itself as revolutionary, and wished to effect a complete transformation of society. It hoped to dismantle social institutions such as heterosexual marriage and the traditional family unit. It also opposed, often forcefully, consumer culture, militarism, racism, and sexism.

Although the Stonewall raid was a catalyst for gay activism, a similar raid at the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles, in the Silver Lake neighborhood, preceded the Stonewall riot by 18 months.

The GLF’s statement of purpose clearly stated: "We are a revolutionary group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature." GLF groups rapidly spread throughout the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia.

Members did not limit activism to gay causes. In late 1960s and early 1970s, many homosexuals joined protests with other radical groups such as the Black Panthers, women’s liberationists and anti-war activists. Lesbians brought the principles of radical feminism on the emerging new philosophy, and GLF activists argued that the institution of heterosexual families necessitated the oppression of homosexuals, allowing them to define their gayness as a form of political resistance. GLF activist Martha Shelley wrote, "We are women and men who, from the time of our earliest memories, have been in revolt against the sex role structure and nuclear family structure."

GLF was shaped in part by the Students for a Democratic Society, a radical student organization of the times. Allen Young, a former SDS activist, was key in framing GLF’s principles. He asserted that "Gay is good for all of us" and "the artificial categories of ‘heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’ have been laid on us by a sexist society, as gays, we demand an end to the gender programming which starts when we are born, the family, is the primary means by which this restricted sexuality is created and enforced, Our understanding of sexism is premised on the idea that in a few society everyone will be gay."

Though the GLF effectively ceased to exist in 1972, unable to successfully negotiate the differences among its members, its activists remained committed to working on political issues and the issue of homosexuality itself.

The legacy of GLF

Despite the GLF's short life span, and differences from more passive homophile groups such as Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis, it transformed the coming out process. It took an experience previously reserved for a small group of friends to a strategic political tool, encouraging gay men and lesbians to take pride in their homosexuality and disclose it publicly. The GLF helped bring about gay and lesbian politics that are still ongoing today.

Even though many activists became disenchanted with the organization, their determination to carry forth the spirit of gay liberation through new groups such as the Gay Activists Alliance and the Radicalesbians proved invaluable in the continuing fight for GLBTQ rights.

GLF's legacy informed gay and lesbian activism throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s when groups such as ACT UP and Queer Nation formed to fight AIDS and homophobia. Many of the leaders of these two groups had been either active in or heavily influenced by the ideas first promoted by GLF.

Queer Nation

Queer Nation arrived on the scene in the summer of 1990, when militant AIDS activists at New York's Gay Pride parade passed out to the assembled crowd an inflammatory manifesto, printed on both sides of a single newspaper-sized piece of newsprint, bearing the titles I Hate Straights! and Queers Read This! Within days, in response to the brash, "in-your-face" tone of the broadside, Queer Nation chapters had sprung up in San Francisco and other major cities.

Described by activist scholars Allan Bérubé and Jeffrey Escoffier as the first "retro-future/postmodern" activist group to address gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender concerns, the short-lived organization made a lasting impact on sexual identity politics in the United States. To a significant degree, the relative frequency and acceptability of glbtq representation in mass culture in the 1990s and early 21st century can be dated to the emergence of Queer Nation.

Queer Nation had no formal structure or leadership and relied on large, raucous, community-wide meetings to set the agendas and plan the actions of its numerous cleverly named committees and sub-groups (such as LABIA: Lesbians and Bisexuals in Action, and SHOP: Suburban Homosexual Outreach Project). Queer Nation's style drew on the urgency felt in the AIDS activist community about the mounting epidemic and the paucity of meaningful governmental response, and was inspired largely by the attention-grabbing direct-action tactics of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP).

Rather than launching long-term campaigns to create social change, Queer Nation favored short-term, highly visible, media-oriented actions, such as same-sex kiss-ins at shopping malls. Their political philosophy was succinctly summed up in the now-cliched slogan, "We're Here. We're Queer. Get Used to It."

Just as importantly, "queer" became an important concept both socially and intellectually, helping to broaden what had been primarily a gay and lesbian social movement into one that was more inclusive of bisexual and transgender people. Rather than denote a particular genre of sexual identity, "queer" came to represent any number of positions arrayed in opposition to oppressive social and cultural norms and policies related to sexuality and gender. The lived political necessity of understanding the nexus of gender and sexuality in this broadening social movement in turn helped launch the field of "queer studies" in higher education.

Identity politics

Not limited to activity in the traditionally conceived political sphere, identity politics refers to activism, politics, theorizing, and other similar activities based on the shared experiences of members of a specific social group (often relying on shared experiences of oppression). Groups who engage in identity politics include not only those organized around sexual and gender identities, but also around such identities as race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, and disability. These groups engage in such activities as community organizing and consciousness-raising, as well as participating in political and social movements.

The most important and revolutionary element of identity politics is the demand that oppressed groups be recognized not in spite of their differences but specifically because of their differences. Identity politics was an important, and perhaps necessary, precursor to the current emphasis on multiculturalism and diversity in American society.

Proponents of identity politics argue that those who do not share the identity and the life experiences that it brings to members of an oppressed group cannot understand what it means to live life as a person with that identity. That is, people who do not share a particular group identity cannot understand the specific terms of oppression and thus cannot find adequate solutions to the problems that members of the group face.

Thus, advocates of identity politics believe in self-determination on the part of oppressed groups. They argue, for example, that glbtq people should determine the curriculum in queer studies departments, be responsible for developing social services programs aimed at queer communities, and be represented politically in all debates about laws and policies pertaining to queer people. Identity politics assumes that the shared identity and experiences of glbtq people is a rational basis for political action, notwithstanding the different (and sometimes competing) interests of individual members of the queer communities. Basic to this assumption is the idea that glbtq people constitute a legitimate political constituency deserving of equal rights and representation. Identity politics has been important in the development of inclusive queer movements, since it insists on the necessity of incorporating the perspectives of the diverse glbtq constituencies in order to serve the varied needs of a notably fragmented community.

Identity politics has sometimes been criticized as naïve, fragmenting, essentialist, and reductionist. Some critics question whether sexual identity itself is a stable element of an individual's personality and have questioned whether it makes sense to base a political movement on so nebulous a concept. Social critic bell hooks, for example, argues that identity is too narrow a basis for politics.

More practically, several political theorists have pointed out that glbtq people are anything but united, rent as they are by multiple and often competing identities based on race, class, gender, and ethnicity.

Traditional liberals have sometimes opposed identity politics in the belief that paying attention to difference merely highlights its salience in interactions. They promote the idea that queer people are "just like everyone else" and should therefore base their politics on factors other than their sexual or gender identities. They seem to believe that ignoring difference will do away with discrimination.

Those engaged in identity politics, however, believe that discrimination can only be overcome by drawing attention to the oppressed difference.

Glbtq people have themselves often criticized identity politics, particularly on the grounds that individuals possess multifaceted identities and thus involvement in politics based on a single identity does not suffice.

Those with multiple oppressed identities have sometimes responded by forming new, more specific identity politics groups, as, for example, lesbians of color. This fragmentation counters the original point of identity politics, which is to encourage recognition of the vast numbers of people who share identities that are outside the mainstream.

However, these communities can also provide support and consciousness-raising to those who become involved in them. Moreover, they can also function to educate other communities, as when lesbians of color demand acceptance and equality within their racial communities, even as they assert their identities as lesbians.

Identity politics is a controversial concept, subject to a range of critiques. However, as long as glbtq people are stigmatized and discriminated against on the basis of their sexual and gender identities, identity politics are likely to be seen as an appropriate response.

Since the late 19th century, people whom we would now call transgendered have advocated legal and social reforms that would ameliorate the kinds of oppression and discrimination they have suffered as a result of their difference from the way most people understand their own gender.

History of the Movement in the United States

In the United States, what little information scholars have been able to recover about the political sensibilities of transgender people in the early 20th century indicates an acute awareness of their vulnerability to arrest, discrimination against them in housing and employment opportunities, and their difficulties in creating "bureaucratically coherent" legal identities due to a change of gender status. They generally experienced a sense of social isolation, and often expressed a desire to create a wider network of associations with other transgender people. In fact, there are quite a few arguments as to when the true beginning of the American Gay Rights Movement starts. The earliest date being claimed is that of 1924 in Chicago when the Society for Human Rights was founded to declare civil rights for gays.[2] However, it is also argued that the beginning of the Gay Rights Movement, LGBT Movement in the United States, after years of being highly controlled and hidden, successfully began in the 1940s in Los Angeles. One of the initial or founding organizations was the Mattachine Society.[3] A secretive society which later began to be associated with Communist values, the society became involved in politics and made its first appearance by supporting Henry Wall and the Progressive Party during the presidential election of 1948. The Mattachine Society was led by Harry Hay and began to slowly gain national attention and membership. Some historians also mark the beginning of the movement as a 1965 gay march held in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia to protest the dismissal of homosexual federal employees. An even later occurrence that is also said to have been the beginning of the movement for Gay Rights was the Stonewall Riots, Stonewall Inn of 1969. On June 27, 1969 New York’s Stonewall Inn bar was raided by police. Though this was a regular incident in gay bars like Stonewall, the reaction of its patrons, as they refused to leave and clashed with the raiding police officers, ultimately led to street riots. This event gave way to mass media attention on the issues facing the LGBT community and therefore increased public awareness, making it possible to have an influential movement.[4] Some offer a less specific time for the beginning of the movement and argue that it was during the wake of World War II that the movement to protect gay and lesbian civil rights emerged. Men and women who participated in the military’s homosexual world began to realize that it was a part of their identity. As they moved back to the cities they began to live their new lifestyle openly and in great numbers only to be severely oppressed by the police and the government.[4] Scholars do not pinpoint a mutual and clearly defined beginning of gay rights activism in the U.S and as said before this may be to their unfortunate political and social positions. Though there is much confusion as to the beginning of the movement, there are clearly defined phases throughout the movement for gay rights in the U.S. The first phase of the movement being the homophile phase, which mainly consisted of the activities of the Mattachine Society, the ONE, ONE Inc. publication, and The Daughters of Bilitis. The homophile movement, which stresses love as opposed to sexuality, focused on protesting political systems for social acceptability. Any demonstrations held by homophile organizations were orderly and polite, but these demonstrations had little impact for they were ignored by the media.[5] In 1969 the second phase of the movement, gay liberation, began. During this phase the number of homophile organizations increased rapidly, as many of the LGBT community became inspired by the various cultural movements occurring during the time period, such as the anti- Vietnam War movement or the Black Power movement. Activism during this phase encouraged “gay power” and encouraged homosexuals to “come out of the closet," so as to publicly display their pride in who they are. They were also more forceful about resisting anti-homosexuality sanctions than activists from the previous phase, participating in marches, riots, and sit-ins. These radicals of the 1970s would later call the previous homophile groups assimilationist for their less vigorous methods. Also during this phase there was an increase in lesbian centered organizations within the movement.[5]

Opposition Throughout Movements History

Though gay and lesbians struggled to go public with their efforts in the U.S, they still were met with opposition. Despite participating in very few public activities in the early 19th century, many gays and lesbians were targeted by police who kept list of the bars and restaurants that were known to cater to the population. Many were arrested for sodomy or hospitalized in mental facilities for homosexuality. They were also fired from many jobs for their lifestyles. States had many laws that made homosexuality a crime and the government would often support the states, as in the 1917 Immigration Act which denied homosexuals entry into the country [6].Homosexual organizations were disrupted as they were said to be breaking disorderly-conduct laws and Gay bars and business had their licenses illegitimately suspended or revoked. This persecution seemed to only intensify after World War II, because many gays and lesbians were living more openly. Thousands of federal employees including soldiers were discharged and fired for suspicions of being homosexuals. Though since that time, there has been more activism by the LGBT Community, through an increasing number of organizations coupled with more visibility and aggressive protest. However, many rights are withheld today along with the inability to get married in most states (with the exception of Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, and Iowa). Also, though there is no longer a ban on homosexuals in the military, however there is a ban on homosexual activities (i.e. the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Policy), and discrimination against gay soldiers is ever present [6]. Activist of the modern Gay Rights Movement still struggle to seek full equality.

1920s

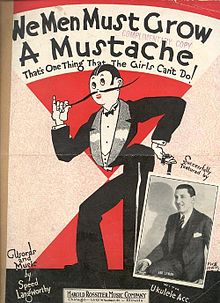

The 1920s ushered in a new era of social acceptance of minorities and homosexuals, at least in heavily urbanized areas. This was reflected in many of the films (see Pre-Code) of the decade that openly made references to homosexuality. Even popular songs poked fun at the new social acceptance of homosexuality. One of these songs had the title "Masculine Women, Feminine Men."[7] It was released in 1926 and recorded by numerous artists of the day and included the following lyrics:[8]

Masculine women, Feminine men

Which is the rooster, which is the hen?

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! And, say!

Sister is busy learning to shave,

Brother just loves his permanent wave,

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! Hey, hey!

Girls were girls and boys were boys when I was a tot,

Now we don't know who is who, or even what's what!

Knickers and trousers, baggy and wide,

Nobody knows who's walking inside,

Those masculine women and feminine men![9]

Homosexuals received a level of acceptance that was not seen again until the 1960s. Until the early 1930s, gay clubs were openly operated, commonly known as "pansy clubs". The relative liberalism of the decade is demonstrated by the fact that the actor William Haines, regularly named in newspapers and magazines as the number-one male box-office draw, openly lived in a gay relationship with his lover, Jimmie Shields.[10] Other popular gay actors/actresses of the decade included Alla Nazimova and Ramon Novarro.[11] In 1927, Mae West wrote a play about homosexuality called The Drag, and alluded to the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. It was a box-office success. West regarded talking about sex as a basic human rights issue, and was also an early advocate of gay rights. With the return of conservatism in the 1930s, the public grew intolerant of homosexuality, and gay actors were forced to choose between retiring or agreeing to hide their sexuality.

Mid-twentieth century advocacy

Transgender advocacy efforts did not begin to gain momentum, however, until the 1950s, in the wake of the unprecedented publicity given to Christine Jorgensen, whose 1952 "sex-change" operation made her an international celebrity and brought transgender issues to widespread attention.

A central yet virtually unknown figure in the history of transgender community formation was Louise Lawrence, a male-to-female transgender person who began living fulltime as a woman in San Francisco in the 1940s. Lawrence developed a widespread correspondence network with transgender people throughout Europe and the United States by the 1950s, and worked closely with Alfred Kinsey to bring the needs of transgender people to the attention of social scientists and sex reformers.

Lawrence was also a mentor to Virginia Prince, who, later in the 1950s and early 1960s, founded the first peer support and advocacy groups for male cross-dressers in the United States.

In 1952, using Lawrence's correspondence network as its initial subscription list, Prince and a handful of other transgender people in Southern California launched Transvestia: The Journal of the American Society for Equality in Dress. Though it lasted only two issues, this publication marks the beginning of the transgender rights movement in the United States.

In 1960, Prince launched another publication, also called Transvestia, that became a long-lasting and influential venue for disseminating information about transgender concerns. In 1962, she founded the Hose and Heels Club, which soon changed its name to Phi Pi Epsilon, a name designed to evoke Greek-letter sororities and to play on the initials FPE, the acronym for Prince's philosophy of "Full Personality Expression". Prince believed that the binary gender system harmed both men and women by alienating them from their full human potential, and she considered cross-dressing to be one means of redressing this perceived social ill.

Support organizations for male cross-dressers proliferated in the 1970s and 1980s, but most traced their roots to various schisms and offshoots of Prince's pioneering organizations of the early 1960s.

Militancy in 1960s San Francisco

Militant transsexual politics first erupted in San Francisco in 1966, when transgender street prostitutes in that city's impoverished Tenderloin neighborhood rioted against police harassment at a popular all-night restaurant, Gene Compton's Cafeteria.

In the wake of that riot, San Francisco activists worked with Harry Benjamin (the nation's leading medical expert on transsexuality), the Erickson Educational Foundation (established by a wealthy female-to-male transsexual, Reed Erickson, who funded the development of a new model of medical service provision for transsexuals in the 1960s and 1970s), activist ministers at the progressive Glide Memorial Methodist Church, and a variety of city bureaucrats to establish a remarkable network of services and support for transsexuals, including city-funded health clinics that provided hormones and federally-funded work training programs that helped prostitutes learn job skills to get off the streets.

Transgender activism

Transsexuals in San Francisco formed C.O.G. (Conversion Our Goal) in 1967, which, after a series of internal schisms, became the Transsexual Counseling Unit, which was located in office space rented by the War on Poverty. When funding from the War on Poverty programs ceased volunteers Jan Maxwell and Suzan Cooke sought greater funding from Reed Erickson's Foundation. The Erickson Educational Foundation grant funded a store front office located in San Francisco's Tenderloin on Turk St. There the Transsexual Counseling Service, with the assistance of the EEF as well as Lee Brewster's Queen Magazine expanded their services beyond the Bay Area by corresponding with transsexuals across the nation. To reflect this the TCS became the "National transsexual Counseling Unit. Reed Erickson was responsible for funding these programs and others which became the early transsexual movement through his foundation the Erickson Educational Foundation.

Transgender activism and gay liberation

By the later 1960s, some strands of transgender activism were closely linked to gay liberation. Most famously, transgender "street queens" played an instrumental role in sparking the riots at New York's Stonewall Inn in 1969, which are often considered a turning point in LGBT political activism. Sylvia Rivera, a transgender veteran of the Stonewall Riots, was an early member of the Gay Liberation Front and Gay Activists Alliance in New York. Along with her sister-in-arms Marsha P. (for "Pay It No Mind") Johnson, Rivera founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) in 1970. That same year, New York gay drag activist Lee Brewster and heterosexual transvestite Bunny Eisenhower founded the Queens Liberation Front, and Brewster began publishing Queens, one of the more political transgender publications of the 1970s.

New York transsexual activist Judy Bowen organized two other short-lived groups, TAT (Transsexuals and Transvestites) in 1970, and Transsexuals Anonymous in 1971, but neither had lasting influence. Far more significant was Mario Martino's creation of the Labyrinth Foundation Counseling Service in the late 1960s in New York, the first transgender community-based organization that specifically addressed the needs of female-to-male transsexuals.

On the West Coast, militant transgender activism found its leading figure in the person of Angela Douglas, a contentious yet effective advocate of transgender rights. Douglas had been active in GLF-Los Angeles in 1969 and wrote extensively about sexual liberation issues for Southern California's counter-cultural press. In 1970 she founded TAO (Transsexual/Transvestite Action Organization), which published the Moonshadow and Mirage newsletters. Douglas moved TAO to Miami in 1972, where it came to include several Puerto Rican and Cuban members, and soon grew into the first truly international transgender community organization.

Another influential West Coast figure was Beth Elliot, one of the first politically active transsexual lesbians, who at one point served as vice-president of the San Francisco chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, the lesbian homophile organization, and edited the chapter's newsletter, Sisters. Elliot became a flashpoint for the issue of MTF (male-to-female) transsexual inclusion in the women's community when, after a divisive public debate, she was ejected from the West Coast Women's Conference in 1973.

The 1970s

The 1970s were a difficult decade for transgender activism. These years were marked by slow, incremental gains as well as demoralizing setbacks from the first flushes of success in the late 1960s. In the early 1970s in Philadelphia, the Radical Queens Collective forged effective political links with gay liberation and lesbian feminist activism. In Southern California, activists such as Jude Patton and Joanna Clark spearheaded competent social, psychological, and medical support services for transgender people.

Across the country, it was becoming easier for transgender people to change the gender designations on state-issued identification documents and to find professional and affordable health care. In 1975, the city of Minneapolis became the first governmental entity in the United States to pass trans-inclusive civil rights protection legislation.

On the other hand, most gay, lesbian, feminist, and other progressive activists distanced themselves from transgender issues. Largely as a result of the emergence of new political ideologies of gender, transgender people– particularly transsexuals– came to be seen as dangerously reactionary in their cultural politics, as people who had a false consciousness of gender oppression and who sought to mutilate their bodies rather than liberate their minds.

Anti-transsexual discourses

Feminist ethicist Janice Raymond caused particular harm with her paranoiac Transsexual Empire, which was published in 1979 but drew on anti-transsexual discourses that had been developing at the grassroots level for nearly a decade. Almost incredibly, Raymond argued—and many of her readers believed—that transsexuals were the mindless agents of a nefarious patriarchal conspiracy bent on the destruction of women.

Raymond characterized female-to-male transsexuals as traitors to their sex and to the cause of feminism, and male-to-female transsexuals as rapists engaged in an unwanted penetration of women's space. She suggested that transsexuals be "morally mandated out of existence." As a result of such views, transgender activists in the 1970s and 1980s tended to wage their struggles for equality and human rights in isolation rather than in alliance with other progressive political movements.

The 1980s and the emergence of the FTM community

In 1980, transgender phenomena were officially classified by the American Psychiatric Association as psychopathology, "gender identity disorder." When the AIDS epidemic became visible in 1981, transgender people—especially transgender people of color involved in street prostitution and injection drug subcultures—were among the hardest hit. One of the few bright spots in transgender activism in the 1980s was the emergence of an organized FTM (female-to-male) transgender community, which took shape nearly two decades later than a comparable degree of organization among the male-to-female transgender movement.

Transgender activism

Lou Sullivan, a gay-identified, HIV-positive San Francisco-based FTM activist, played a leading part in this effort. In 1986, inspired by the leadership of FTM pioneers such as Mario Martino, Steve Dain, Rupert Raj, and Jude Patton, he founded the FTM support group that grew into FTM International, the leading advocacy group for female-to-male individuals, and began publishing The FTM Newsletter.

Sullivan was an important community-based historian of transgenderism and also played an instrumental role in persuading medical and psychotherapeutic professionals to provide services to transgender individuals like himself who identified as gay or lesbian in their preferred social genders. In the years since Sullivan's untimely death in 1991, his successor Jamison Green has emerged as the most vocal and influential FTM activist in the United States.

The effects of AIDS activism

The AIDS crisis provoked a profound reorientation of sexual identity politics in the later 1980s and early 1990s that ultimately worked to the advantage of transgender activism. AIDS activism required alliances between different social groups affected by the epidemic, such as gay men, hemophiliacs, Haitians, and injection-drug users. An effective response to the epidemic meant addressing systemic social problems such as poverty and racism that transcended narrow sexual identity politics. In the context of this public health crisis, transgender issues once again began to resonate within broader struggles for justice and equality. Leslie Feinberg's influential pamphlet, Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come, published in 1992, heralded a new era in transgender politics.

Militant groups such as ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) and Queer Nation crafted a highly visible, playfully ironic, angry style of media-oriented, direct-action politics that proved congenial to a new generation of transgender activists. The first transgender activist group to embrace the new queerqueer politics was Transgender Nation, founded in 1992 as an offshoot of Queer Nation's San Francisco chapter.

Transgender Nation

Transgender Nation noisily dragged transgender issues to the forefront of San Francisco's queer community, and at the local level successfully integrated transgender concerns with the political agendas of lesbian, gay, and bisexual activists to forge a truly inclusive glbtq community. Transgender Nation organized a media-grabbing protest at the 1993 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association to call attention to the official pathologization of transgender phenomena. Transgender Nation paved the way for subsequent similar groups such as Transexual Menace and It's Time America that went on to play a larger role in the national political arena.

Anti-transgender hate crimes

Transexual Menace, co-founded by Riki Wilchins and Denise Norris in 1994, the year that Transgender Nation folded, tapped into and provided an outlet for the outrage many transgender people experienced in the brutal murder of Brandon Teena, a transgender youth, and two of his friends in a farmhouse in rural Nebraska on December 31, 1993. The murders, depicted in Kimberly Peirce's Academy Award-winning feature film Boys Don't Cry (2000), called dramatic attention to the serious, on-going problem of anti-transgender violence and hate crimes.

The website Remembering Our Dead, compiled by activist Gwen Smith and hosted by the Gender Education Association, honors the memory of the transgender murder victims—roughly one person a month. The Remembering Our Dead project spawned the National Day of Remembrance, an annual event begun in 1999, which is now observed in dozens of cities around the world.

GenderPAC

Riki Wilchins, whom Time magazine selected in 2001 as one of its "100 Civic Innovators for the 21st Century," went on to found GenderPAC (Gender Public Advocacy Coalition), the largest national organization in the United States devoted to ending discrimination against gender diversity. GenderPAC fulfills a vital need for advocacy, both within the transgender community and outside it, on gender-related issues. Rather than focusing on single-identity-based advocacy, GenderPAC recognizes and promotes understanding of the commonality among all types of oppression, including racism, sexism, classism, and ageism.

GenderPAC, which has sponsored an annual lobbying day in Washington, D.C., since the late 1990s, is but the most visible of many transgender political groups to emerge over the last decade. More than 30 cities, and a handful of states, have now passed transgender civil rights legislation. While the transgender movement still faces many significant challenges and obstacles to gaining full equality, the wave of activism that began in the early 1990s has not yet peaked.

Programs

Through its myriad programs– such as GenderYOUTH, Workplace Fairness, Violence Prevention, and Public Education initiatives– GenderPAC works to dispel myths about gender stereotypes. The GenderYOUTH program, for example, strives to empower young activists so that they can create GenderROOTS college campus chapters themselves, and go on to educate others about school violence. Via its Workplace Fairness project, GenderPAC helps to educate elected officials about gender issues, change public attitudes, and support lawsuits that may expand legal rights for people who have suffered discrimination on the basis of gender.

In terms of violence prevention, GenderPAC collaborates with a Capitol Hill-based coalition of bipartisan organizations to further public education and media awareness about gender-based violent crimes. It emphasizes to members of Congress the need for passage of the Local Law Enforcement Enhancement Act (that is, the Hate Crimes Act).

Further, as part of its public education efforts, the organization has held an annual National Conference on Gender in Washington, D. C. since 2001. The conference is a gathering of over 1,000 activists throughout the country and from numerous colleges, who work together for three days on issues of gender policy, education, and strategy.

Criticism from members of the transgender community

GenderPAC has drawn criticism from some members[who?] of the transgender community for its broad-based definition of oppression on the basis of gender. In early 2001, several transgender activists drafted an open "letter of concern" to GenderPAC, expressing their consternation over the organization's perceived mainstreaming and disconnection from the trans community. This alleged disconnection stems from GenderPAC's refusal to employ identity politics and its failure to focus on specifically transgender issues.

Wilchins has publicly responded to these complaints, arguing that a broad spectrum of people– including, but not limited to those who identify as transgender– benefit from gender-rights activism.[citation needed]

For instance, GenderPAC has helped to publicize the case of a butch lesbian who does not identify as transgender but who was harassed at her workplace, and eventually fired, for looking "too masculine." Another case for which GenderPAC recently advocated involves a biological woman who was terminated from her job for not wearing makeup or a feminine hairstyle.[citation needed]

Wilchins sees these cases as relevant to GenderPAC's mission, because her group's efforts are a "post identity form of organizing" that emphasizes true diversity, and focuses on commonalities rather than differences.[citation needed]

LGBT rights and the Supreme Court

While the United States Supreme Court has been reluctant to issue rulings outside of the heterosexual mainstream on gay rights issues, it has made some important decisions in this area. It is important to understand that the Supreme Court only agrees to hear a few cases each term, and that by not hearing a case, the lower court's ruling stands.

- 1956 - Supreme Court rules that a homosexual publication is not automatically obscene and thus protected by the First Amendment.

- 1961 - Illionis is the first state to abolish its sodomy laws.

- 1967 - Supreme Court rules that Congress may exclude immigrations on the grounds that they are a homosexual. Congress amends its laws in 1990.

- 1972 - Supreme Court rules that a Minnesota law defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman is constitutional.

- 1976 - Supreme Court refuses to hear and thus affirms a lower courts ruling that a Virginia state sodomy law is constitutional. (see Doe v. Commonwealth’s Attorney).

- 1983 - Supreme Court refusals to hear, and thus affirms a Oklahoma Appeals Court ruling that an Oklahoma law that gave the public school broad authority to fire homosexual teachers was too broad and thus unconstitutional.

- 1986 - In Bowers v. Hardwick the Supreme Court rules that sodomy laws are constitutional. The court overturns this ruling in the 2003 case of Lawrence v. Texas.

- 1993- President Clinton adjusts the ban on gays in the military to be that of a ban on homosexual activity in the military, known as the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy

- 1996 - In Romer v. Evans the high court overturns a state constitutional amendment prohibiting elected lawmakers in Colorado from including LGB people in their civil rights laws.

- 1998 - The Supreme Court rules that federal sexual harassment laws do include same-sex sexual harassment.

- 2001 - The Supreme Court rules that the Boy Scouts of America does not have to follow state anti-discrimination laws when it comes to sexual orientation.

- 2003 - Lawrence vs. Texas repeals state sodomy laws that were used to prosecute homosexuals for having sex in the privacy of their homes.[12]

LGBT Rights and State Courts

- 1992- Colorado became the first state to abolish offered civil-rights protection for homosexuals by amending its constitution

- 1998- Maine became the first state to repeal its existing gay-rights statutes

- 1999- Vermont Supreme Court grants the same rights and protections that married heterosexuals have to homosexual partners.

- 1999- Antisodomy laws of 32 states were repealed

- 1999- 11 states had laws to protect homosexuals from discrimination

- 2000- Vermont Supreme Court backed civil unions between homosexual couples

- 2003- Massachusetts Highest Court rules that homosexuals do have the right to marry according to the constitution.

- 2003- Antisodomy Laws in all states were overturned.

- May 2004- Massachusetts begins issuing licenses for same sex marriages

- 2006- New Jersey’s Supreme Court extends civil rights to homosexuals and allows civil unions

- 2008- California and Connecticut Supreme Courts abolished their states’ bans on same-sex marriages

American political parties, interest groups and LGBT rights

The Democratic Party and the Republican Party ignored the issue of gay rights until the 1970s, when the left-wing of the Democratic Party started to show interest in the cause, and gay right concerns were incorporated into every national Democratic Party platform since 1980. The national Republican Party platform has formally opposed gay rights issues since 1992.

The National Stonewall Democratic Federation is the official LGBT organization for the Democratic Party, while the Log Cabin Republicans is the organization for LGB (but no T) citizens that want to moderate the Republican Party social polices. In terms of minor political parties, the Outright Libertarians is the official LGBT organization for the Libertarian Party, and is among the groups that follow the Libertarian perspectives on gay rights. The Green Party LGBT members are represented by the Lavender Green Caucus. The Socialist Party USA has a Queer Commission to focus on LGBT rights issues [1].

In terms of interest groups, the Human Rights Campaign is the largest LGBT organization in the United States, claiming over 725,000 members and supporters,[14] though this membership count is disputed.[15][16]. The HRC endorses federal candidates, and while it is technically bi-partisan and has endorsed some Republican Party, its overall pro-choice, center-left philosophy tends to favor the Democratic Party candidates. The National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce is a progressive LGBT organization that focuses on local, state and federal issues, while the Independent Gay Forum and the Gays and Lesbians for Individual Liberty both subscribe to conservative or libertarian principles. And the Empowering Spirits Foundation not only engages in empowering individuals and organizations to engage in the political process for equality, but engages in service-oriented activities in communities typically opposed to equal rights to help bring about change.[17][18][19]

American law and LGBT rights

As a federal republic, absent of many federal laws or court decisions, LGBT rights often are dealt with at the local or state level. Thus the rights of LGBT people in one state may be very different from the rights of LGBT people in another state.

- Criminal Law - Homosexual relations between consenting adults in private is not a crime, per Lawrence v. Texas[12]. The age of consent for heterosexuals and homosexuals should be the same, but each state decides what that age shall be. This does not apply to military law, where sodomy is still a felony under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

- Civil rights - Sexual orientation is not a protected class under Federal civil rights law, but it is protected for federal civilian employees and in federal security clearance issues. Some states and cities have chosen to include sexual orientation or gender identity as a protected class in antidiscrimination laws. They are not required to do so, but the United States Supreme Court implied in Romer v. Evans that a state may not prohibit gay people from using the democratic process to get such protections enacted. Some private employers have chosen to adopt a non-discrimination policy that includes sexual orientation, but may not be enforceable in a court of law.

- Hate crimes - Federal hate crime law now includes sexual orientation and gender identity. The Matthew Shepard Act, officially the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, is an Act of Congress, passed on October 22, 2009, and was signed into law by President Barack Obama on October 28, 2009, as a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2010 (H.R. 2647). This measure expands the 1969 United States federal hate-crime law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.

- Same-sex couples: Federal law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, and allows states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages. See also Same sex marriage in the United States. Likewise some states specifically ban gay people from adopting or having custody of children, while other states do not.

- Freedom of Speech - Homosexuality per se is not as obscene, and thus protected under the First Amendment. However, states can reasonably regulate the time, place and manner of speech. Pornography is protected, when it is not obscene, but it is based on local community standards.

- Education - Public schools and universities generally have to recognize an LGBT student organization, if they recognize other social or political organization, but high school students may be required to get parental consent. Harassment of LGBT students may or may not be prohibited depending on state or city law. Sex education classes often are required to teach abstinence until marriage to receive government funding.

- Armed Forces - Since 1994, "Don't ask, don't tell" has the been the official policy in the American armed forces. Servicemen or women discovered to be homosexual or bisexual are separated from the armed forces under an administrative discharge. Sodomy is still a crime under the Uniform Code of Military Justice and gay servicemen and women can be given an administrative discharge and/or sentenced to prison.

See also

- LGBT social movements

- LGBT rights in the United States

- Libertarian perspectives on gay rights

- Socialism and LGBT rights

- Gay Blue Jeans Day

- The Society for Human Rights

- Join The Impact

- Timeline of LGBT History

References

- ^ Dignan, Joe; Rene Sanchez (13 February 2004). "San Francisco Opens Marriage to Gay Couples". Washington Post. p. A.01. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

first gay couple to be [married]

- ^ Gay Rights Movement in the United States. Dudley Clendinen.2008. Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia.3 March 2009

- ^ When Did the Gay Rights Movement Begin?.Vern Bullough. 18 April 2005. History New Network, George Mason University.3 March 2009

- ^ a b Paul S. Boyer. "Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement. The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press. 2001. Encyclopedia.com. 4 March 2009

- ^ a b 'Gay Rights Movement in the United States. Dudley Clendinen.2008. Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia.3 March 2009

- ^ a b "BACKGROUND." CQ Researcher 10.14 (14 April 2000): 313. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 4 Mar. 2009

- ^ The song was written by Edgar Leslie (words) and James V. Monaco (music) and featured in Hugh J. Ward's Musical Comedy "Lady Be Good."

- ^ Artists who recorded this song include: 1. Frank Harris (Irving Kaufman), (Columbia 569D,1/29/26) 2. Bill Meyerl & Gwen Farrar (UK, 1926) 3. Joy Boys (UK, 1926) 4. Harry Reser's Six Jumping Jacks (UK, 2/13/26) 5. Hotel Savoy Opheans (HMV 5027, UK, 1927, aka Savoy Havana Band) 6. Merrit Brunies & His Friar's Inn Orchestra on Okeh 40593, 3/2/26

- ^ A full reproduction of the original sheet music with the complete lyrics (including the amusing cover sheet) can be found at: http://nla.gov.au/nla.mus-an6301650

- ^ Mann, William J., Wisecracker : the life and times of William Haines, Hollywood's first openly gay star. New York, N.Y., U.S.A. : Viking, 1998: 2-6.

- ^ Mann, William J., Wisecracker : the life and times of William Haines, Hollywood's first openly gay star. New York, N.Y., U.S.A. : Viking, 1998: 12-13, 80-83.

- ^ a b Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=000&invol=02-102#opinion1 (U.S. Supreme Court 2003).

- ^ gay-rights movement.The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 4 March 2009

- ^ HRC | What We Do

- ^ HRC 'members' include all who ever donated $1 - Washington Blade

- ^ HRC Responds | The Daily Dish | By Andrew Sullivan

- ^ ESF | About Us

- ^ Wiser Earth Organizations: Empowering Spirits Foundation

- ^ Idealist.org – Empowering Spirits Foundation

Further reading

- Bullough, Vern L. Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context. Harrington Park Press, 2002.

- Cante, Richard C. (March 2008). Gay Men and the Forms of Contemporary US Culture. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0 7546 7230 1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Dynes, Wayne R. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Homosexuality. New York and London, Garland Publishing, 1990

- Johansson, Warren & Percy, William A. Outing: Shattering the Conspiracy of Silence. Harrington Park Press, 1994.

- Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1982. ISBN 0-312-01900-9

- Thompson, Mark, editor. Long Road to Freedom: The Advocate History of the Gay and Lesbian Movement. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. ISBN 0-312-09536-8

- Timmons, Stuart. The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1990.

External links

- On Important Pre-Stonewall Activists

- Queer Commission of the Socialist Party USA

- LGBT Political Investment Caucus

- Revolting Queers 2007

- Gay Rights Movement Confronts Teen Suicides, Homophobic Electioneering and Violent Attacks - video report by Democracy Now!

- Some of this article has been used with permission of Susan Stryker from glbtq.com and has been released under the GFDL.