The Hump: Difference between revisions

m de-italicise title in opening |

CountryBot (talk | contribs) adding Article Feedback category for pilot project |

||

| Line 231: | Line 231: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hump}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hump}} |

||

[[Category:Article Feedback Pilot]] |

|||

[[Category:World War II Southeast Asia Theatre]] |

[[Category:World War II Southeast Asia Theatre]] |

||

[[Category:World War II operations and battles of the Southeast Asia Theatre]] |

[[Category:World War II operations and battles of the Southeast Asia Theatre]] |

||

Revision as of 01:52, 25 March 2011

| The Hump | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Burma Campaign | |||||

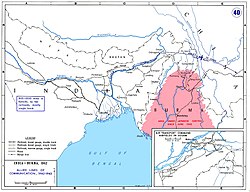

Allied lines of communication in Southeast Asia (1942–43). The Hump is shown at far right. | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Strength | |||||

| |||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

|

594 aircraft lost, missing, or written off 1,659 personnel killed or missing | |||||

The Hump was the name given by Allied pilots in the Second World War to the eastern end of the Himalayan Mountains over which they flew military transport aircraft from India to China to resupply the Chinese war effort of Chiang Kai-shek and the units of the United States Army Air Forces based in China. Creating an airlift presented the USAAF a considerable challenge in 1942: it had no units trained or equipped for moving cargo, and no airfields existed in India for basing the large number of transports that would be required. Flying over the Himalayas was extremely dangerous and made more difficult by a lack of reliable charts, an absence of radio navigation aids, and a dearth of information about the weather.[2]

The task was initially given to the U.S. Tenth Air Force, and then to the USAAF's Air Transport Command (ATC). Because the USAAF had no previous airlift experience upon which to base planning, it assigned commanders to build and direct the operation who had been key figures in the founding of the ATC. In addition, another commander had extensive executive experience with civilian air carriers.[3]

The successive organizations responsible for carrying out the mission (originally referred to as the "India-China Ferry")[4] were: the Assam-Burma-China Command[5] (April–July 1942) and the India-China Ferry Command (July–December 1942) of the Tenth Air Force; and the Air Transport Command's India-China Wing (December 1942-June 1944), and India-China Division (July 1944-November 1945).

The airlift began in April 1942, after the Japanese blocked the Burma Road, and continued on a daily basis from May 1942 to August 1945, when the effort began to scale down. Final operations were flown in November 1945. The Hump airlift delivered approximately 650,000 tons of materiel to China during its 42-month history.[6] For its efforts and sacrifices, the India-China Wing of the ATC was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation on January 29, 1944, at the personal direction of President Franklin D. Roosevelt,[7] the first such award made to a non-combat organization.[6]

Background: the China supply dilemma

The Second Sino-Japanese War and Japanese operations in Indochina closed all sea and rail access routes for supplying China with materiel except through Turkestan in the Soviet Union. That access ended following the signing of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in April 1941, and the Burma Road became the only land route.[2]

The rapid success of Japanese military operations in Southeast Asia threatened this lifeline and prompted discussion of an air cargo service route from India as early as January 1942. On February 25, President Roosevelt wrote General George C. Marshall that "it is of the utmost urgency that the pathway to China be kept open", and committed ten C-53 Skytrooper transports for lend-lease delivery to the Chinese National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) to build its capability to 25 aircraft.[7] When the Tenth Air Force opened its headquarters in New Delhi in March 1942, it was assigned the responsibility of developing an "India-China Ferry" using both U.S. and Chinese aircraft.[8] Although never given command authority over aircraft or personnel, the officer responsible for the India-China Ferry was Tenth Air Force chief of staff Brig. Gen. Earl L. Naiden, who held that responsibility until mid-August.[9]

From its onset, the air route was predicated on creating two branches: a trans-India route from India's western ports to Calcutta, where cargo would be transshipped by rail to Assam; and a route from bases in Assam to southern China. The original scheme envisioned the Allies holding northern Burma and using Myitkyina as an offloading terminal to send supplies by barge downriver to Bhamo and transfer to the Burma Road. However, on May 8, 1942, the Japanese seized Myitkyina and coupled with the loss of Rangoon, effectively cut Allied access to the Burma Road.[7] To maintain the uninterrupted supply to China, U.S. and other allied leaders agreed to organize a continual aerial resupply effort, or "air bridge," directly between Assam and Kunming.[8]

Airlift history

Haynes, 1942

Tenth Air Force was hampered by a constant diversion of men and aircraft to Egypt, where Nazi Germany was threatening to seize the Suez Canal. Its Air Service Command was still en route by ship from the United States, forcing it to acquire aircraft and personnel for the India-China Ferry from any available source. Pan American World Airways in Africa provided ten DC-3s and flight crews to outfit the new operation. The airlift's command structure was divided, with part of the authority given to Gen. Joseph Stillwell, part remaining with Washington D.C., and all of the responsibility resting with Tenth Air Force (specifically Naiden), which had also been ordered by AAF Commanding General Henry H. Arnold to "co-operate" with the British in defending India.[4]

On April 23, 1942, a prospective bombardment group commander, Colonel Caleb V. Haynes, was assigned to command the Assam-Kunming branch of the India-China Ferry, dubbed the Assam-Burma-China Command.[10] Col. Robert L. Scott, a pursuit pilot awaiting an assignment in China, was assigned as his operations officer and a month later as executive officer. The first mission "over the hump" took place on April 8, 1942. Flying from the Royal Air Force airfield at Dinjan, Lt. Col. William D. Old used a pair of the borrowed DC-3s to ferry 8,000 U.S. gallons of aviation fuel intended to resupply the Doolittle Raiders.[4][8][11] Haynes was a fortuitous choice as the first commander, as he had just completed an assignment as a key subordinate of Brig. Gen. Robert Olds. Olds and his staff had founded the new Air Corps Ferrying Command, which was then in the process of becoming the Air Transport Command.[3]

The collapse of Allied resistance in northern Burma in May 1942 meant further diversion of the already minuscule air effort. The Assam-Burma-China Command resupplied Stillwell's retreating army and evacuated its wounded, while establishing a regular air service to China using ten borrowed DC-3s, four USAAF C-47 Skytrains,[4][12] and 13 CNAC C-53s and C-39s.[2] Only two-thirds of the aircraft were serviceable at any time. Dinjan itself was within range of Japanese fighters now based at Myitkyina, forcing all-night maintenance operations and pre-dawn takeoffs of the defenseless supply planes.[8] The threat of interception also forced the Assam-Burma-China Command to fly a difficult 500-mile (800 km) route to China over the Eastern Himalayan Uplift, which came to be known as the "high hump", or more simply, "The Hump".[2][13]

The official Army Air Forces history of the airlift stated:

The Brahmaputra valley floor lies 90 feet (27 m) above sea level at Chabua. From this level the mountain wall surrounding the valley rises quickly to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and higher. Flying eastward out of the valley, the pilot first topped the Patkai Range, then passed over the upper Chindwin River valley, bounded on the east by a 14,000-foot (4,300 m) ridge, the Kumon Mountains. He then crossed a series of 14,000—16,000-foot (4,300—4,900m) ridges separated by the valleys of the West Irrawaddy, East Irrawaddy, Salween, and Mekong Rivers. The main "Hump", which gave its name to the whole awesome mountainous mass and to the air route which crossed it, was the Santsung Range, often 15,000 feet (4,600 m) high, between the Salween and Mekong Rivers. East of the Mekong the terrain became decidedly less rugged, and the elevations more moderate as one approached the Kunming airfield, itself 6,200 feet (1,900 m) above sea level.[7][14]

Innumerable problems with the Indian railway system meant that aircraft assigned to the Trans-India Command often carried their cargo all the way to China, while much cargo took as long to reach Assam from Karachi as the two-month journey by ship from the United States. India's highway and river systems were so undeveloped as to be unable to support the mission, leaving air as the only practicable way to supply China in anything resembling a timely fashion.[8]

The operation procured most of its officers, men, and equipment from the USAAF, augmented by British, Indian Army, and Commonwealth forces, Burmese labor gangs, and an air transport section of CNAC. On May 17, 1942, the 1st Ferrying Group of the Air Transport Command, consisting of the 3rd, 6th, and 13th Ferrying Squadrons, reached its base at the New Malir Cantonment near Karachi, and was assigned to the operational control of the Tenth Air Force over the objections of ATC, which feared that its planes and crews would be steered into combat units. (This did in fact happen to some extent.)[4] For the remainder of 1942, its 62 C-47s[15] became the backbone of the airlift, flying for both branches of the operation until August 1, 1942, when it relocated to Assam.

The first two months of the airlift produced only 700 tons of cargo delivered by the USAAF and 112 by CNAC,[16] and tonnage actually fell for both June and July, mostly as a result of the full onset of the summer monsoon.[4][17]

Tate, 1942

On June 17, 1942, Haynes continued on to China to take up an assignment as bomber commander of Brig. Gen. Claire L. Chennault's China Air Task Force. Scott was left in command for several days before he too was ordered to China to command the first U.S. fighter group in the CATF. On June 22 Col. Robert F. Tate (who like Haynes was a bombardment officer) was named to replace Haynes, but he was also in charge of the Trans-India Command in Karachi and remained in that capacity. Lt. Col. Julian M. Joplin, acting at the direction of Naiden, for all practical purposes commanded Hump operations until August 18. Tate took actual command on August 25, when Naiden was forced to return to the United States,[18] although like Naiden he delegated direction of airlift operations to Joplin. Effective July 16, 1942, the two commands of the India-China Ferry merged into the India-China Ferry Command.[4]

Tate was immediately handicapped because the best pilots and 12 aircraft of the Assam-Burma-China Command went west to Egypt with Brereton on June 26. Despite the use of the 1st Ferrying Group, tonnage delivered to China grew very slowly.[7] Three bases constructed by the British on tea plantations at Chabua,[19] Mohanbari,[20] and Sookerating[21] became operational in August 1942 (although the latter two were not yet capable of all-weather operations), and construction of a fourth began at Jorhat. CNAC continued to fly from Dinjan, with its lend-lease C-53s and their crews contracted to the USAAF to assure that they would carry only essential cargo and not commercial activity.[7] The airlift lost its first aircraft to accident on September 23, presumed to be from icing,[4] after which losses of transports increased sharply.[2]

A long-anticipated air attack by the Japanese on the four Assam airfields took place late in the afternoon of October 25. Little had been done to create an antiaircraft defense, and requests for an early warning system had gone unheeded. 100 bombers and fighters, bombing from 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and strafing from 100 feet (30 m), achieved complete surprise. The only defense provided came from three P-40s aloft on patrol, and six others which took off and gave pursuit. Dinjan and Chabua were severely damaged by bombing, and nine transports were destroyed or written off by low-level strafing. The next day Sookerating was strafed by 30 fighters, again without warning, but damage was confined to a single storage building containing food and medical supplies.[22] A third raid struck Chabua on October 28 but missed the field entirely. Although the India Air Task Force, commanded by now-Brig. Gen. Haynes, subjected the captured airfield at Myitkyina to a summer-long series of bombings, the Japanese overcame the attempt to neutralize them by equipping their fighters with external fuel tanks and mounting the raids from Lashio.[23]

Haynes responded by moving a P-40 squadron of the 51st Fighter Group from Karachi to Sookerating, while the China Air Task Force launched a series of attacks against Lashio. The Japanese raids were not repeated in 1942.[4] In June 1943, following small, sporadic raids during the dry season, the entire fighter strength of the Tenth Air Force, amounting to only approximately 100 P-40s, was organized as the Assam American Air Base Command (later the 5320th Air Defense Wing), specifically to protect the Assam airfields.[23]

Alexander, 1942-43

The operation was evaluated by the USAAF in October 1942 and the attitudes of Tenth Air Force's commanders characterized as "defeatist".[7] When the Air Transport Command offered to take over the task, Marshall accepted, and ATC activated the India-China Wing, ATC (ICW-ATC) on December 1, 1942, commanded by Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Edward H. Alexander. Like Haynes, Alexander had been a founding member of ATC. The 1st Ferrying Group returned to ATC and was redesignated the 1st Transport Group. Its 76 C-47s were augmented in January 1943 by the addition of three C-87 transports (converted B-24 Liberator bombers), which increased to 11 in March and 25 in July.[7]

On March 31, 1943, the 308th Bombardment Group reached its base at Kunming and began two months of "reverse" Hump operations, flying round trip to India to acquire the gasoline, bombs, parts and other materiel it needed to stockpile before flying combat missions. Using kits developed by the South India Air Service Command Depot, it converted its B-24 Liberators into fuel transports to accomplish the task.[24]

Gen. Arnold observed first-hand the hazards of "flying the Hump" when the combat crew flying Argonaut, the B-17 that transported his party, became lost as they flew to Kunming following the Casablanca Conference.[7][25] From his experiences, Arnold later wrote:

"A C-87 Liberator transport must consume three and a half tons of 100-octane gasoline flying the Hump over the Himalaya Mountains between India and Kunming (to get) four tons through to the Fourteenth Air Force. Before a bombardment group can go on a single mission in its B-24 Liberators, it must fly the Hump four times to build up its supplies."[26]

On April 21, 1943, the first of thirty C-46 Commandos (an untried cargo transport whose performance was superior to the C-47's in cargo capacity and ceiling) arrived in India.[6][7] In May the 22nd Ferrying Group[27] began C-46 operations from Jorhat. In June, despite the fact that the British—and later the American Services of Supply—failed to complete construction of all-weather runways at Mohanbari and Sookerating,[7] the activation of the 28th,[28] 29th,[29] and 30th[30] Transport Groups proceeded, an attempt to expand the C-46's role to meet projected levels of tonnage. The use of "groups" and component "squadrons" to identify units continued until December 1, 1943, when these were disbanded and ATC flying units were identified by the station numbers of their bases.[31]

A severe shortage of flight crews led Alexander to plea for additional personnel. "Project 7" was set up by ATC at the end of June to fly nearly 2,000 men, 50 transports, and 120 tons of materiel from Florida to India. Despite this, July's tonnage was less than half of the its goal. The airfields were nowhere near completion, nearly all of the new pilots had been single-engine instructor pilots, specialized maintenance personnel and equipment had been sent by ship, and the complexities of the new C-46 (see Transport shortcomings below) had become evident. Scorching heat and torrential rains of the summer monsoon completed the undermining of the ambitious goals. Airfield construction problems were not overcome for several months.[7]

Hoag and Hardin, 1943-44

At his meeting with Arnold, Chiang warned that the price of China's cooperation with Stillwell to reconquer Burma was a 500-plane air force and delivery by the airlift of 10,000 tons a month.[7] In May 1943, at the Trident Conference, President Roosevelt ordered ATC to deliver 5,000 tons a month to China by July; 7,500 tons by August; and 10,000 tons by September 1943.[6] Frustration at the failure of the ICW-ATC to meet these goals led Arnold to send another inspection team to India in September 1943, led by ATC commander Maj. Gen. Harold L. George. Accompanying George was Col. Thomas O. Hardin, an aggressive former airline executive who had already been overseas a year as head of ATC's Central African Sector. On September 16, George immediately re-assigned Hardin to command the new Eastern Sector of the ICW-ATC, to invigorate Hump operations. Gen. Alexander was replaced in command of the ICW-ATC by Brig. Gen. Earl S. Hoag on October 15.[7] In addition to the changes in command, George instituted the "Fireball", a weekly C-87 express flight by the 26th Transport Group carrying spare parts for the transports from the Air Service Command Depot at Fairfield, Ohio, to the ATC service depot at Agra, India.[2]

Japanese fighters based in central Burma began to challenge the transport route near Sumprabum at the end of the summer monsoon. On October 13, 1943, a large number of fighters evaded U.S. fighter patrols and shot down a C-46, a C-87, and a CNAC transport while damaging three others. Similar interceptions on October 20, 23, and 27 shot down five more C-46s. Japanese pilots referred to the shooting down of vulnerable transport aircraft as tsuji-giri ("cutting down a casually-met stranger") or akago no te wo hineru ("twisting a baby's arm").[32] Tenth Air Force immediately began attacks on Japanese airfields (Myitkyina was attacked 14 times before the end of the year) but ICW moved its route to Kunming even farther north and only two more C-46s were shot down during the remainder of 1943.[33]

On December 13, 1943, 20 Japanese bombers and 23 fighter escorts attacked the Assam airfields. Despite an increase in fighter patrols and creation of an early warning system, the defenders had only thirteen minutes warning. U.S. interceptors were unable to climb to the 18,000-foot (5,500 m) altitude of the bombers in time to prevent the bombing, but only slight damage resulted. The raiding force was pursued and attacked, then ran head-on into fighter patrols returning from northern Burma. Serious losses to the raiders apparently convinced the Japanese not to repeat the attacks.[34]

Hardin altered operations by introducing night missions and refusing to cancel scheduled flights because of adverse weather or threat of interception. Although losses to accidents and enemy action increased, and replacements for the high number of C-46s lost ceased entirely for two months,[7] tonnage delivered rose sharply, surpassing its objective in December when over 12,500 tons arrived in Kunming. By the end of 1943, Hardin had 142 aircraft in operation: 93 C-46, 24 C-87, and 25 C-47.[6]

As a result of these efforts, President Roosevelt directed that the Presidential Unit Citation be awarded to the India-China Wing. Hardin was given a month's leave in the United States, promoted to brigadier general, and as the representative of the wing received the award from General Arnold on January 29, 1944, the first ever awarded to a non-combat unit.[6][7] Hardin returned to the India China Wing in February 1944, just as the first of a trickle of four-engined C-54 Skymaster transports arrived in theater (see Operations on the low hump and in China below).

On March 21, 1944, Hardin advanced to command of the ICW-ATC when Hoag was transferred to head ATC's European Wing.[35] A month later, to move closer to its growing number of airbases, ICW-ATC changed its headquarters from New Delhi to Rishra, north of Calcutta. There, on the site of a former jute mill known as "Hastings Mills", Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer established the headquarters of the Army Air Forces India-Burma Theater in an 8.5-acre (34,000 m2) building.[31] Under Hardin, tonnages increased but so did expectations and frustrations; morale and safety concerns continued to plague the operation.[2] In the first 54 days of 1944, 47 transports were lost.[36] One transport was being lost for every 218 flights (an accident rate of 1.968 planes lost per thousand hours). One life was being lost for every 162 trips flown, or 340 tons delivered.[37][38]

In June 1944, at the behest of future ICD-ATC commander William Tunner, Col. Andrew B. Cannon was assigned to command the Assam Wing in anticipation of a massive increase in C-54s. Like Haynes, Alexander, and Tunner, he had been an early selectee of Gen. Robert Olds in the Air Corps Ferrying Command, where he was a base commander.[39]

On July 1, 1944, ATC reorganized its nine wings worldwide into air divisions, and sectors into wings. The ICW-ATC became the India China Division, ATC (ICD-ATC), with Hardin remaining as division commander. The Eastern Sector, carrying out the Hump operation, was redesignated the Assam Wing, while the Western Sector support organization became the India Wing. ICW-ATC also had an operational training unit (OTU) at Gaya and service depots at Panagarh, Agra, and Bangalore.[7]

On August 1, 1944, it discontinued the use of station numbers as unit designations and formed numbered AAF Base Units. In conformance with USAAF policy service-wide, AAF base units collectively identified all organizations, including flying units, at any particular non-combat base.[31] To illustrate the various organizational changes affecting the Hump airlift between 1942 and 1944, the 1st Ferrying Group at Chabua became the 1st Transport Group on December 1, 1942; Station No. 6 (APO 629 New York) on December 1, 1943; and the 1333rd Base Unit on August 1, 1944. The Headquarters Squadron, Eastern Sector, India-China Wing, established at Chabua on September 16, 1943, became the Headquarters Squadron, Assam Wing on July 1, 1944; and the 1325th Base Unit (HQ Assam Wing) on August 1, 1944.[7][31]

Tunner, 1944-45

Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner next commanded the India-China Division. Tapped in the spring of 1944 to succeed Hardin, he selected his key staff and made a theater inspection trip in June that included piloting a C-46 over the Hump.[40] He took command on September 4, 1944, with orders not just to increase the tonnage delivered, but also to reduce the numbers of lives and aircraft lost in accidents,[37] and to improve morale in the India-China Division.[2] Tunner and his staff, using a "big business" approach,[14] completely turned around the operation, improved morale, and cut the aircraft loss ratio in half while doubling the amount of cargo delivered.

Tunner made extensive use of 47,000 local laborers[7] and utilized at least one elephant to lift 55-gallon fuel drums into the aircraft.[2][41] A daily direct flight called the "Trojan" was instituted between Calcutta and Kunming, flown by select C-54 crews, that carried a minimum of five tons of highest priority materiel or passengers, then brought back critically wounded patients or aircraft engines needing overhaul.[42] Tunner set both daily and monthly tonnage quotas for each base to move over the Hump, based on the type of aircraft it operated and its distance from the "Chinaside" airfields, as the crews referred to their destinations. He immediately reinstituted military standards of dress, decorum (including inspections and parades), and behavior that had become slack in the previous year, for which he earned the nickname "Willie the Whip."[43]

In Tunner's first month of command, although the ICD delivered 22,314 tons to China, it still incurred an accident rate of .682 per thousand hours of flight.[37] By January 1945, Tunner's division had 249 aircraft and 17,000 personnel. It delivered more than 44,000 tons of cargo and passengers to China that month at an aircraft availability rate of 75%, but also incurred 23 fatal crashes with 36 crewmen killed.[7] On January 6, a particularly fierce winter storm blew across the Himalayas from west to east, increasing the time of westbound trips by one hour, and caused 14 CNAC and ATC transports to be lost or written off, with 42 crewmen missing, the highest one-day loss of the operation.[12][44] The accident toll increased in the two months that followed, with 69 planes lost and 95 crewmen killed.[7]

To combat losses due to mechanical failure, in February 1945 Tunner introduced a maintenance program termed Production Line Maintenance. PLM consisted of having each aircraft due for 50- or 200-hour maintenance towed through five to seven maintenance stations, depending on whether or not an engine change was required. Each station had a fresh maintenance crew trained for a specific service task, including engine run up, inspections, cleaning, technical repair, and servicing, a process that took nearly a full 24-hour day per aircraft to complete. Each base specialized in only one type of aircraft to simplify the process. Despite initial resistance, PLM was successfully implemented throughout the division.[6][37][45]

Tunner also adopted two measures to reduce losses due to inexperience and crew fatigue. To accomplish the first, he appointed Lt. Col. Robert D. "Red" Forman as division training officer to oversee both stringent training and a flying safety program led by Capt. Arthur Norden.[46] After March 15, 1945, the program intensified when Major John J. Murdock, Jr., took over the position of division flying safety officer.[47] Secondly, Tunner altered the personnel rotation policy of the ICD-ATC. Before Tunner took command, pilot tours were set at 650 flight hours over the hump, which many pilots abused by flying daily to rotate back to the United States in as few as four months. As a result the division flight surgeon reported that half of all crewmen suffered from operational fatigue. Effective March 1, 1945, Tunner increased the number of flight hours required to 750, and dictated that all personnel had to be in theater twelve months to be eligible for rotation, which discouraged over-scheduling.[48]

Under Tunner, the India-China Division expanded to four wings in December 1944. The expansion was necessary to control the multiplicity of AAF Base Units created as more airfields were opened.[49] In addition to the Assam and India Wings, ICD-ATC added the Bengal Wing, headquartered at Chabua, to control C-54 operations, and the China Wing at Kunming. Tunner shifted his veteran commanders to provide leadership to the new wings. Cannon moved to command of the Bengal Wing, and Col. George D. "Lonnie" Campbell, Jr. took over the Assam Wing. Col. Richard F. Bromiley switched from the India Wing to the China Wing.[50]

In July 1945, the last full month of operations, 662 aircraft of the Hump airlift delivered 71,042 tons, the airlift's maximum monthly tonnage. Of the aircraft, 332 were ICD-ATC transports, but 261 were from AAF units whose combat mission had ended and were temporarily assigned to the airlift.[51] An average of 332 flights to China was scheduled daily. The India China Division ATC had 34,000 USAAF personnel assigned, and including indigenous civilians of all nationalities employed in India, Burma, and China, 84,000 persons overall. It boasted an aircraft availability rate of more than 85%. ICD suffered 23 major accidents in July, with 37 crewmen killed, but the Hump accident rate declined to .358 aircraft per thousand hours of flight.[6][37]

On August 1, 1945, to celebrate "Air Force Day",[52] ICD-ATC laid on its largest mission of the airlift. It flew 1,118 round-trip sorties, averaging two per aircraft, and one C-54 logged three round trips in 22¼ hours of operations. 5,327 tons were delivered in one day without fatality, and with only one major accident when a C-46 made a wheels-up landing.[37] C-87s and C-109s carried 15% of the tonnage without mishap.[24] Before the month ended, nearly 50,000 more tons were delivered. Eight major accidents resulted in only 11 deaths, at a rate of one death for every 2,925 trips (1/18 of what it had been in January 1944).[38] The major accident rate of only 0.18 aircraft lost per 1000 hours was one-third of what it had been when Tunner took command, and one-eighth of that of January 1944.[1][38][53]

He considered ICD-ATC's safety record to be his greatest achievement. In his memoir Over the Hump, Tunner wrote:

"If the high accident rate of 1943 and early 1944 had continued, along with the great increase in tonnage delivered and hours flown, America would have lost not 20 planes that month but 292, with a loss of life that would have shocked the world."[53]

Tunner commanded the division until November 10, 1945.[54] The deputy commander of ICD-ATC and prior commander of the Assam Wing, Brig. Gen. Charles W. Lawrence, briefly commanded the division before it was disbanded on November 15, 1945.[55]

Operations on the low hump and in China

The first diversion of India-China Wing resources to operations in the region other than the Hump airlift began in February 1944. The Japanese attack in Arakan, followed by the threat to Imphal in March, resulted in assistance to the British that Hardin estimated reduced hump deliveries by 2,500 tons. The crisis occasioned by the Japanese attack on Imphal led Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the commander-in-chief of the Allied South East Asia Command, to request 38 C-47 aircraft to reinforce Imphal. Supposedly, not even Mountbatten could divert planes from the Hump,[56] but he was backed up by two of the principal American commanders in the theater (Major General Daniel I. Sultan, the deputy commander of the CBI Theater and Major General George E. Stratemeyer of the Eastern Air Command (EAC), Air Commander for Mountbatten and air advisor to Stillwell).[57] After the request was approved, ICW-ATC provided 25 C-46s as the equivalent of 38 C-47s.[58] They were attached to the EAC Troop Carrier Command (commanded by Brig. Gen. William Old, who had flown the first Hump mission in 1942) to support the British and were used to fly the personnel and light equipment of the 5th Indian Division to Imphal and Dimapur, where they arrived in time to thwart the Japanese offensive.[59]

The next month, to reinforce Stillwell's planned offensive into Burma, the ICW-ATC flew 18,000 Chinese troops west across the Hump to Sookerating, which resulted in a net reduction of another 1,500 tons.[7]

However, the re-capture in May 1944 of Myitkyina airfield by American and Chinese troops of Stillwell's command deprived the Japanese of their principal fighter airfield threatening Allied aircraft flying the Hump. The field immediately became an emergency landing strip for Allied aircraft even though fighting continued in the nearby town until August 1944. Its capture also opened regular use of a second, more direct airlift route, designated Route Baker but unofficially dubbed the "Low Hump",[7] by Douglas C-54 Skymaster four-engined transports, which had ceiling limitations that precluded flying Route Able (the High Hump).[2]

In October 1944, after Gen. Tunner took command of the India-China Division of Air Transport Command, increased numbers of C-54s, sometimes escorted by Allied fighters based at Myitkyina, greatly increased tonnage levels flown to China from India. The C-54, which could at ten tons carry five times the cargo load of the C-47 and twice that of the C-46, replaced both twin-engined transports as the primary lifter of the operation.[14] The expansion of bases resulted in the formation of eastbound Routes Easy, Fox, Love, Nan, and Oboe, and of westbound Route King.

China operations

From June 1944 to January 1945, the India China Division was tasked with supporting Operation Matterhorn, the B-29 Superfortress strategic bombing campaign against Japan from bases around Chengdu in central China. B-29s stripped of guns and other equipment and fitted with four bomb bay tanks hauled their own fuel, but ATC aircraft also moved nearly 30,000 tons to Chengdu before XX Bomber Command abandoned its China bases and returned to India.[7] During the last three months of bombing operations from China, ICD supplied all of XX Bomber Command's materiel except bombs, which B-29s toted over the mountains in "reverse hump" missions. Lt.Col. Robert S. McNamara created a statistical control section to create adjustable schedules that tracked the variables of gross and net loads, aircraft availability, and loading/unloading time requirements[60]

50 C-47s were permanently based Chinaside after October 1944 to assist the lift and remained for internal missions. Most of the remaining C-47s were eventually sent to bases in Burma and continued Hump missions over the lower routes. They proved their continuing usefulness by playing prominent roles in various support missions within China in 1944 and 1945.

Arnold originally envisioned Matterhorn operations being supplied by hundreds of C-109s (see Transport shortcomings below) and by its own "air transport service". To accomplish the latter, three special mission C-46 squadrons were created in early 1944 under the code name "Moby Dick" to carry out fuel operations for XX Bomber Command. Designated the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Air Transport Squadrons (Mobile), each was a self-contained unit of twenty C-46s, flight crews, maintenance and engineering specialists, and a full complement of station operation personnel. They arrived in the CBI in June 1944, with the 1st and 2nd ATS assigned to the ICD-ATC base at Kalaikunda, India, and the 3rd ATS sent to Kunming. When ATC reorganized on August 1, the MATS squadrons maintained a separate identity from the newly-created AAF Base Units, but each flew hundreds of Hump missions, primarily delivering aviation fuel.[61] Because Hump operations were of extraordinary length from Kalaikunda—requiring an intermediate stop at Jorhat—the squadrons were made part of ICD-ATC when XX Bomber Command began to reduce its operations in November 1944. On October 30, the 2nd ATS was moved to Dergaon, Bengal, and later to Luliang, China, where it was disbanded in June 1945 and became Squadron B, 1343rd AAF Base Unit.[62]

Operation Grubworm

Between December 5, 1944, and January 5, 1945, C-46s and crews were attached to the Tenth Air Force to augment "Operation Grubworm".[63] This was the relocation of the 14th and 22nd Chinese Divisions, located in reserve on the Stillwell Road near Myitkyina, to bases around Kunming. Chiang and China Theater commander Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer proposed to the Combined Chiefs of Staff, over the objections of Mountbatten, to relocate the divisions to counter a Japanese offensive to capture the Kunming airfields. The operation was approved with the proviso that it not strain Tenth Air Force's extensive air transport system supplying Allied ground operations in Burma. IDC-ATC provided the C-46s of the mobile air transport squadrons and all of its China Wing C-47s to provide the necessary augmentation.[64]

The 2nd ATS moved in entirety from its base at Dergaon to Luliang Field, China, completing the deployment by December 13.[62] The 1st ATS operated from Ledo, and ICD's 1348th AAF Base Unit at Myitkyina South airfield coordinated the entire operation and provided the staging base for refueling all transports. The C-46s moved the 14th Division from five airfields in Burma, including a field at Nansin whose construction was completed December 4. Takeoffs there were subject to artillery and sniper fire. The 1348th Base Unit scheduled operations 24 hours a day and in bad weather, although the operation was suspended between December 16 and 22 when the situation in China seemed improved. Of the six pick-up fields, only Myitkyina South was capable of night operations,[63] and troop carrier C-47s were used to shuttle troops there during the day for ICD-ATC aircraft to fly over the Hump at night.[65]

The mobile air transport squadrons were familiar with the Burma airfields and so were selected to fly the operation. Showing unusual flexibility in planning, the 1348th Base Unit quartered incoming troops near airfields, supplied them, monitored the availability of aircraft and crews, divided the troops into planeloads, and kept Chinese units and their materiel intact. Briefings and fuelings were conducted at Myitkyina South, the planes flew to their pickup fields and loaded, and then flew back to Myitkyina South for a final refueling before flying on to China. The 1348th Base Unit control tower performed all air traffic control of aircraft to and from China.[65]

Grubworm lifted 25,009 Chinese troops, 396 Americans, 1,596 draft animals, 42 jeeps and 144 pieces of artillery in 24 days of flying. ICD-ATC crews provided 597 of the 1328 sorties of the operation. Although three C-47s were lost during the operation, ICD-ATC had no losses.[66] When the Japanese offensive shifted to seize the Fourteenth Air Force bases at Suichwan and Kanchow, the 2nd ATS evacuated the bases in a single day on January 22.[62][67]

Between March and May 1945, the ICD-ATC carried the first American combat troops into China when it redeployed the brigade-sized MARS Task Force from Burma.[7] In April, 50 C-47s and 30 C-46s of the ICD[68] conducted "Operation Rooster", transporting both divisions of the Chinese 6th Army from Kunming, where they had been delivered by "Grubworm", to Chihkiang in the western Hsiang valley to reinforce the defense of the 14th AF base there. ICD-ATC flew 1,648 sorties, delivering 25,136 troops; 2,178 horses; and 1,565 tons of materiel; for a total of 5,523 tons. 369 tons of aviation gasoline was also carried to Chihkiang for 14th AF use.[37]

Operational difficulties

Building a capability

The task facing the Tenth Air Force of creating an airlift was daunting at minimum, emphasizing all that the Army Air Forces lacked in April 1942: no units tasked for moving cargo, no experience in organized airlift by the AAF or its predecessor Air Corps, and no airfields for basing units. In addition, flying in the region was made more difficult by a lack of reliable charts, an absence of radio navigation aids, and a dearth of weather data.[2]

In 1942 Chiang Kai-shek insisted that at least 7,500 tons per month were needed to keep his field divisions in operation, but this figure proved unattainable for the first fifteen months of the Hump airlift.[69] The 7,500 total was first exceeded in August 1943, by which time objectives had been increased to 10,000 tons a month. Ultimately monthly requirements surpassed 50,000 tons.[7]

Slowly, however, an airlift of unprecedented scale began to take shape. Construction of four new bases was begun in 1942, and by 1944 the operation flew from six all-weather airfields in Assam. During July 1945, the air corridor from India began at the thirteen airfields strung out along Northeast Indian Railways section of the Brahmaputra valley,[70] with eight in Assam, four in the Bengal valley, and one near Calcutta.[37][71] and terminated at six Chinaside airfields around Kunming.[37][72]

Through July 1944 the flight corridor for The Hump was fifty miles wide with a highly restrictive vertical clearance. As bases expanded and the Low Hump route came into use, the corridor widened to 200 miles (320 km) and 25 charted routes, with a vertical clearance of 10,000—25,000 MSL in the south, permitting highly congested but controlled operations at all hours.[73]

Transport shortcomings

A critical problem proved to be finding a cargo aircraft capable of carrying heavy payloads at the high altitudes required, and four types were eventually used in the airlift: C-47 and variants, C-46, C-87/C-109, and C-54.

Initially, the Hump was flown with the Douglas C-47 Skytrain and its related variants, the C-39, C-53, and civilian DC-3 (converted to carry cargo). However, the performance specifications of the Douglas transports were not suited to high-altitude operation with heavy payloads, and could not normally reach an altitude sufficient to clear the mountainous terrain, forcing the planes to attempt a highly dangerous route through the maze-like Himalayan passes.[74]

The introduction in January 1943 of the Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express, a design modification of the B-24D heavy bomber, boosted tonnage figures. Its high-altitude capability enabled it to surmount the lower mountains (15,000–16000 feet MSL) without resorting to the passes, but the type had a high accident rate and was unsuited to the airfields then in use. Despite the C-87's four engines, the aircraft climbed poorly with heavy loads, as did its bomber counterparts, and often crashed on takeoff if an engine was lost. Because of its slim Davis wing, it also had a tendency to spin out of control when encountering even mild icing conditions over the mountains.[75] One Hump pilot called the C-87 "an evil, bastard contraption...(that) could not carry enough ice to chill a highball."[76]

Another transport variant, the C-109, was a B-24 converted to haul fuel. All combat equipment was removed and eight flexible bag fuel tanks were installed inside the fuselage to carry 2,900 U.S. gallons of high-octane aviation gasoline. Most of the 218 C-109 conversions were sent to the CBI beginning in mid-1944. Like the C-87, they were not popular with their crews, since they were very difficult to land when fully loaded, especially at airfields such as Kunming's above 6,000 feet (1,800 m) in elevation, and often demonstrated unstable flight characteristics with full tanks. A crash landing of a loaded C-109 inevitably resulted in an explosion and crew fatalities, earning it the nickname "C-One-Oh-Boom".[2][77]

The Curtiss C-46 Commando began to fly Hump missions in May 1943. The C-46 was a large twin-engine aircraft capable of flying faster and higher than any previous twin-engine cargo aircraft, and was capable of carrying heavier loads than either the C-47 or the C-87.[78][79] With the C-46, aircraft loads increased significantly the Hump reached 12,594 tons in December, 1943. Loads continued to increase throughout 1944 and 1945, reaching an all-time maximum tonnage in July, 1945.[78][80] Performance of the Commando was enhanced when camouflage paint, standard on all USAAF aircraft until February 1944, was removed to reduce weight and provide five extra knots of speed.[2] While becoming the workhorse of the Hump airlift, its frequent mechanical failures (in particular, a tendency to engine failure) resulted in such unflattering sobriquets as "Dumbo" and "Plumber's Nightmare".[81] When it first arrived in theater, the C-46 also required such extensive training of inexperienced crews, a transition school had to be established that drained the airlift of ten aircraft and crews. Worse, spare parts were in such scarce supply until the fall of 1943 that 26 of the first 68 C-46s sent were out of commission.[7]

Flight hazards

Flying over the Hump proved to be an extremely hazardous undertaking for Allied flight crews. The air route wound its way into the high mountains and deep gorges between north Burma and west China, where violent turbulence, 125 to 200 mph (320 km/h) winds,[12][44] icing, and instrument weather conditions were a regular occurrence. From the beginning, a lack of experienced personnel and resources hampered the mission. In the first months of the operation, inexperienced supply officers often ordered planes loaded until they were "about full," heedless of gross weight limitations or center of gravity placement. Lack of suitable navigational equipment, radio beacons, and inadequate numbers of trained personnel (there were never enough navigators for all the groups) continually affected airlift operations. While the airlift initially took advantage of reserve pilots who were experienced civilian airline transport pilots, most were just out of flight school or were single-engine rated with relatively little instrument time. In December 1942, one-third of the 102 technical sergeant pilot training graduates of the Lubbock Field Class 42-I were immediately sent to India to fly the Hump.[12] Chinese pilots, while used to a variety of aircraft, also had little instrument flying experience, and most were unfamiliar with the large American transport aircraft used in the airlift.[2]

Still, American and Chinese pilots often flew daily on round-trip flights, and around the clock. Some exhausted crews flew as many as three roundtrips every day, particularly during the Hardin rotation policy. Mechanics serviced planes in the open, using tarps to cover the engines during the frequent downpours, and suffered burns to exposed flesh from sun-heated bare metal. There were not enough mechanics or spare parts to go around during the first two years of operations; maintenance and engine overhauls were often deferred. Many overloaded planes crashed on takeoff after losing an engine or otherwise encountering mechanical trouble. Author and ATC pilot Ernest K. Gann recalled flying into Chabua and witnessing four separate air crashes in one day: two C-47s and two C-87s.[82] Due to the isolation of the area, as well as the lower priority of the CBI theater, parts and supplies to keep planes flying were in short supply before the onset of the "Fireball", and flight crews were often sent into the Himalayan foothills to cannibalize aircraft parts from the numerous crash sites. At times, monthly aircraft losses totalled 50% of all aircraft then in service along the route. A byproduct of the numerous air crashes was a local boom in native wares made from aluminium crash debris.[2]

In addition to losses from weather and mechanical failure, the unarmed and unescorted transport aircraft flying the Hump were occasionally attacked by Japanese fighters.[80] While piloting a C-46 on one such mission, Lt. Wally A. Gayda returned fire in desperation against a fighter by pushing a Browning automatic rifle out the cockpit window and firing a full magazine, killing the Japanese pilot.[83][84] Some C-87 pilots installed of a pair of forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns fuselage-mounted in front of the cargo doors of their aircraft, but there is no documented instance of their being used.[85]

Search and rescue

The high number of losses resulted in the formation at Jorhat in July 1943 of one of the first search and rescue organizations, nicknamed "Blackie's Gang". A former test pilot and Hump veteran, Capt. John L. "Blackie" Porter, was given the assignment using C-47s borrowed from airlift units, which he manned with a dozen former barnstormers and enlisted crewmen armed with submachine guns and hand grenades.[86] Blackie's Gang accounted for virtually every crewman recovered in 1943, including CBS News correspondent Eric Sevareid and 19 others forced to parachute on August 2. The unit moved to Chabua on October 25 and was given official status, equipped with two C-47s and several L-5 Sentinel liaison planes for rescue pickups. Porter recruited volunteer medics to parachute into crash sites to aid injured crewmen. In late November he increased his small fleet with two B-25 Mitchells that had been consigned to a salvage field. Blackie Porter was killed in action on December 10, 1943, in a B-25 which was set on fire by Japanese Zero fighters during a search mission and crashed at the Indian border trying to return to base.[7][14]

When Tunner took command of ICD-ATC, he was dissatisfied with the existing search-and-rescue set-up, deeming it "a cowboy operation". He appointed the operations officer at Mohanbari, former Hump pilot Major Donald C. Pricer, to establish "a thoroughgoing and efficient search and rescue organization". Pricer's 90 men of the 1352nd Army Air Forces Base Unit (Search and Rescue) at Mohanbari used four B-25s, a C-47, and an L-5 to conduct the search missions, painted for easy identification in yellow overall with blue wing bands. Pricer also charted all known crash sites to eliminate checking previous wrecks, and on occasion called upon a Sikorsky YR-4 helicopter based at Myitkyina to assist in rescue missions.[87]

The Hump Express, in its last edition on November 15, 1945, reported:

The unit has been responsible for all search and rescue work from Bhamo, in Burma, north as far as allied planes regularly fly. Roughly, its jurisdiction extended from Tezpur, India to Yunnanyi, China. Before organized search and rescue, crews had been lost for weeks, sometimes months. Stretches up to 90 days were not unknown in a country where jungle thickets and dizzy mountain trails made each hour a nightmare to the lost crews fighting their way out. But today, ICD's unique outfit probably would have made the story a trifle less stark. Aerial supply drops of maps and pertinent homing information would have made the walk-out perhaps less circuitous, while certainly the hardships would have been alleviated by air-dropped medical supplies, food and clothing. S & R members have parachuted to lost aircrews to furnish medical aid and walkout assistance. As a direct result of the unit's work, the percentage of saved personnel steadily mounted and with it the confidence and assurance of ICD flight crews.[88]

Statistical summary of operations

ATC operations accounted for 685,304 gross tons of cargo carried eastbound during hostilities, including 392,362 tons of gasoline and oil, with nearly 60% of that total delivered in 1945. ATC aircraft made 156,977 trips eastbound between December 1, 1943, and August 31, 1945, losing 373 aircraft.[1] Though supplemented by the opening of the Ledo Road network in January 1945 and by the recapture of Rangoon, the airlift's total tonnage of 650,000 net tons dwarfed that of the Ledo Road (147,000 tons).[2] In addition to cargo, 33,400 persons were transported, in one or both directions.

CNAC pilots made a key contribution to Hump flight operations. During 1942 to 1945 the Chinese received 100 transport aircraft from the United States: 77 C-47s and 23 C-46s. Of the eventual 776,532 gross tons and approximately 650,000 net tons transported over the Hump, CNAC pilots accounted for 75,000 tons (about 12%).[38] The Hump airlift continued beyond the end of the war. The final missions of the ICD-ATC, made after most of its attached organizations had departed, were the transporting of 47,000 U.S. personnel west over The Hump from China to Karachi for return to the United States.[7]

The maximum aircraft strength of the India-China Division, ATC (July 31, 1945) was 640 aircraft:[1] 230 C-46s, 167 C-47s, 132 C-54s, 67 C-87/C-109s, 33 B-25s, 10 L-5s, and 1 B-24.[89]

Gen. Tunner's final report stated that the airlift "expended" 594 aircraft.[38][90] At least 468 American and 41 CNAC aircraft were known lost from all causes, with 1,314 air crewmen and passengers killed. In addition, 81 more aircraft were never accounted for, with their 345 personnel listed as missing. Another 1,200 personnel had been rescued or walked back to base on their own.[2][78]

The final summary of logged flight time in the airlift totalled 1.5 million hours. The Hump ferrying operation was the largest and most extended strategic air bridge (in volume of cargo airlifted) in aviation history until exceeded in 1949 by the Berlin airlift, an operation also commanded by Gen. Tunner.[6] Tunner, writing in Over the Hump, described the significance of the Hump Airlift:

"Once the airlift got underway, every drop of fuel, every weapon, and every round of ammunition, and 100 percent of such diverse supplies as carbon paper and C rations, every such item used by American forces in China was flown in by airlift. Never in the history of transportation had any community been supplied such a large proportion of its needs by air, even in the heart of civilization over friendly terrain...After the Hump, those of us who had developed an expertise in air transportation knew that we could fly anything anywhere anytime."[91]

Notable Hump airlift participants

- Col. Robert L. Scott, Jr., pilot and commanding officer

- Col. Merian C. Cooper (movie producer), liaison officer

- Lt. Col. Robert S. McNamara (corporate executive), scheduling analyst for "Reverse Hump" operations

- Capt. Ernest K. Gann (author), C-46 pilot

- Capt. Larry Clinton (band leader), flight instructor 1343rd Base Unit

- 2d Lt. Theodore F. Stevens (senator), C-47/C-46 pilot

- Flt/Off. Gene Autry (television and movie star), C-109 pilot

- T/Sgt. Tony Martin (entertainer), Special Services performer

- S/Sgt. Leonard Pennario (concert pianist), recruited to Martin's troupe

- Captain Frank Kingdon-Ward (botanist), British soldier recruited to locate crash sites

See also

- Fort Hertz covered an airstrip in Northern Burma which served as an emergency landing ground for planes flying the Hump.

- South-East Asian Theatre of World War II

References

- ^ a b c d "Table 211 - ATC Operations From Assam, India to China (Over the Hump): Jan 1943 to Aug 1945" (PDF). Army Air Forces Statistical Digest, World War II. U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Correll, John T. "Over the Hump to China", AIR FORCE Magazine, October 2009, pp. 68-71.

- ^ a b Tunner, Lt. Gen. William H. (1964). Over the Hump. 1st Edition, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, pp. 19-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weaver, Herbert (1944). "Army Air Forces Historical Study 12: The Tenth Air Force 1942" (PDF). Air Force Historical Research Agency. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - ^ Also called the Assam-Burma-China Ferry Command. The "command" was ad hoc and an unofficial designation.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The Logistics of War: A Historical perspective. U.S. Air Force. 2000. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help), pp. 110-113. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Heck, Frank H. "Chapter 5: Airline to China". The Army Air Forces in World War II: Volume VII, Services Around the World. Hyperwar Foundation. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Weaver, Herbert. "Chapter 14: Commitments to China". The Army Air Forces in World War II: Volume I, Plans and Early Operations January 1939 to August 1942. Hyperwar Foundation. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- ^ Weaver and Rapp 1944, p. 32. "India-China Ferry" was an unofficial descriptive of the system used in official correspondence, and not an organized command. On July 16, 1942, the "India-China Ferry Command" became an official command by order of the Tenth Air Force.

- ^ Often seen colloquially as the ABC Ferrying Command.

- ^ The original plan had been to haul fuel over the Hump for use by the Aquila Force, an advanced heavy bomber detachment of the Tenth AF intended to bomb Japan from eastern China. Haynes had been the detachment commander and Scott a volunteer member before the plan was cancelled in favor of the B-25 raid.

- ^ a b c d DeBerry, Col. Drue L. (2002). The Air Force, Andrews AFB, Maryland: Air Force Historical Foundation, Hugh Lauter Levins Associates, Inc. ISBN 0-88363-104-0, p. 49.

- ^ Heck, p. 139. While the region, and the operation, was universally known as "the hump", crews flying the airlift called the mountainous barrier the "Rockpile".

- ^ a b c d Glines, Carroll V. "Flying the Hump", AIR FORCE Magazine, March 1991. Vol. 74, No. 3, pp. 102—105.

- ^ The group began with 75 transports but thirteen were diverted to the Middle East en route to India. Of the 62 that reached India, 15 were destroyed by the end of 1942.

- ^ Weaver and Rapp 1944, p. 169. Appendix 2. The totals include 420 tons of gasoline (including the 30,000 gallons of fuel and 2 tons of oil allotted for the Doolittle force), 208 passengers, a million rounds of ammunition, 4.5 tons of Bren guns, 8 tons of bombs, 1.5 tons of radio equipment, a 1.5-ton jeep, two small aircraft, 46 tons of aircraft spare parts, 7 tons of medical supplies, 38 tons of food, 15 tons of "other" and "special" equipment, and two tons of cigarettes.

- ^ "Net tons" excludes the weight of fuel transported to China to enable the return of the transports to India.

- ^ Weaver states the return was for a "stomach disorder". However other sources indicate the abrasive Naiden may have been insurbordinate to a British general officer, and one alleges that Stillwell had him relieved for "financial impropriety". Whatever the case, Naiden was reduced back to colonel on November 6 and held two training commands before his death in 1944.

- ^ All-weather base, headquarters of 1st Ferrying Group, with 3rd Ferrying Squadron based there.

- ^ Base of the 6th Ferrying Squadron until the end of the dry monsoon.

- ^ Base of the 13th Ferrying Squadron until the end of the dry monsoon.

- ^ U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II: Combat Chronology 1941 - 1945 Center for Air Force History, Washington D.C. (1991).

- ^ a b Weaver, Herbert (1946). USAF Historical Study 117: The Tenth Air Force, 1943 AFHRA, p. 17.

- ^ a b Bowman, Martin (1989). B-24 Liberator 1939-45. Norwich" Patrick Stephens, Ltd. ISBN 1-85260-073-X, p. 107.

- ^ Coffey, Thomas M. (1982). Hap: The Story of the U.S. Air Force and the Man Who Built It General Henry H. 'Hap' Arnold. Viking Press, ISBN 0670360694, pp. 291-292. En route to Kunming, Arnold stopped at New Delhi to confer with Stillwell. He arrived at Dinjan on February 4, intending to remain overnight, but when he found that Stillwell and Field Marshal Sir John Dill had flown on, impulsively decided to fly the Hump at night. Tenth Air Force commanding general Clayton Bissell and his personal pilot accompanied Arnold and assured him they knew the route, part of which was over Japanese-occupied territory. After an early evening takeoff, Arnold's navigator experienced altitude sickness in the unpressurized bomber. Navigation beacons failed to work, the radio operator could not raise Kunming by radio, and the B-17 unknowingly encountered a 100-knot tail wind, 50 knots more than had been forecast. Bissell's pilot proved useless. Argonaut had actually flown well past Kunming, and as fuel began to seem critical, the radio operator finally made contact with Kunming station and used its signal as a direction finder. Argonaut landed shortly before two in the morning, four hours overdue.

- ^ Birdsall, Steve (1973). Log of the Liberators: An Illustrated History of the B-24. Garden City: Doubleday and Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-385-03870-4, p. 164.

- ^ The "Ferrying" designation for the group and its 77th, 78th, and 88th Ferrying Squadrons was changed to "Transport" on July 1.

- ^ Based at Tezpur; 96th, 97th, 98th Transport Squadrons.

- ^ Based at Sookerating; 99th, 100th, 301st Transport Squadrons.

- ^ Based at Mohanbari; 302nd, 303rd, 304th Transport Squadrons.

- ^ a b c d CBI Order of Battle, Air Transport Units

- ^ Allen, Louis (1984). Burma: The Longest War 1941-45. Dent Paperbacks. p. 390. ISBN 0-460-02474-4.

- ^ Weaver 1946, pp. 55–56

- ^ Weaver 1946, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Coffey 1982, p. 331. The transfer was not entirely routine. The fearful losses suffered by the ICW in the first seven weeks of 1944 prompted Arnold to send C. R. Smith on an emergency inspection trip to India, where Smith met with Hoag. He was appalled to find that the ICW commander was headquartered a thousand miles to the west of his bases, had never flown the Hump himself, and received all his information from written reports. Smith did fly the Hump, and it was he who recommended Hardin take over the wing.

- ^ Coffey 1982, p. 330

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hanson, LTC (USAF) David S. ""When You Get a Job to Do, Do It": The Airpower Leadership of Lt. Gen. William H. Tunner" (PDF). U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Hump Express, November 15, 1945 (final) edition.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 70

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 64

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 97. Essentially a publicity stunt, Tunner had an elephant and mahout recruited at Misamari, with the animal named, appropriately enough, "Miss Amari". Photographs also appeared of an elephant named "Elmer" lifting a drum, but their veracity and that of the practice as being standard is not documented.

- ^ Hump Express, April 12, 1945.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 110

- ^ a b "Hump's Worst Weather Bats Planes About", The Hump Express. January 25, 1945.

- ^ PLM later became standard practice throughout the AAF. (Glines, p. 104)

- ^ Tunner 1964, pp. 66–68

- ^ "Flying Safety Officers launch Intensified Drive" Hump Express, March 15, 1945

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 90

- ^ ICD was in charge of 60 AAF base units at some point between December 1943 and December 1945.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 131

- ^ The 7th and 308th Bomb Groups and 443rd Troop Carrier Group operated from India, while the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Combat Cargo Groups were based at Myitkyina. These groups carried more than 20,000 tons in July and 11,000 tons in August. (Heck, "Airline to China").

- ^ Histories (including Tunner's) refer to "Army Air Forces Day", but contemporary documents including the Hump Express consistently call it "Air Force Day".

- ^ a b Tunner 1964, p. 134

- ^ Fogerty, Robert P. (1953). USAF Historical Study 91: Biographical Data on Air Force General Officers, 1917-1952, AFHRA.

- ^ "Lawrence new CG", Hump Express, November 15, 1945

- ^ Weaver 1946, pp. 19, 21. ICW-ATC's chain of command did not go through the theater commander but directly to Washington D.C.

- ^ Weaver 1946, pp. 20–21. Stratemeyer had been ordered to the CBI more or less as an ambassador at large to handle just such problems.

- ^ Taylor, Dr. Joe G. (1957), USAF Historical Study 75: Air Supply in the Burma Campaign, AFHRA, p. 62. Taylor writes the British originally wanted 63 C-47s. After review by Gen. William D. Old and Air Marshal John Baldwin, the recommended figure was 38, which was agreed to by Lt. Gen. William J. Slim. The EAC chief of staff, USAAF Brig. Gen. Charles B. Stone, then concluded 30 was sufficient. Mountbatten changed it back to 38 for the formal request to the U.S. chiefs of staff.

- ^ Allen, Louis (1984). Burma: The Longest War 1941-45. Dent Paperbacks. pp. 242–244. ISBN 0-460-02474-4.

- ^ Nalty, Bernard C. (1997). "Victory over Japan". In Bernard C. Nalty (ed.). Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force. Air University Press. p. 342. ISBN 0-16-049009-X.

- ^ "'Sylvester's Circus' Makes Records In Three Theaters" China Command Post, February 23, 1945

- ^ a b c 2nd Air Transport Squadron (Mobile)

- ^ a b Taylor 1957, p. 50. The operation was planned as "Operation Glow Worm", but changed when Tenth Air Force Col. S.D. Grubbs was placed in charge.

- ^ Bowen, Dr. Henry Lee (1953). "Chapter 9. Victory in China", The Army Air Forces in World War II: Volume V, The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945 (Section II, Aid to China: The Theater Air Forces in CBI). University of Chicago Press. pp 253-254. The China Wing C-47s were assigned to haul newly trained Chinese troops from North China to Yunnan Province.

- ^ a b Bowen 1953, pp. 254–255

- ^ Bowen 1953, p. 256. 2nd ATS did have a C-46 go missing on a regular Hump mission on December 16.

- ^ "Flout Enemy to Evacuate Suichwan", Hump Express, February 15, 1945.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 121. The C-47s were those internally based in China.

- ^ Greg Goldblatt, reproduction of United States Army Center of Military History brochure. Background, CBI Order of Battle, Lineages and History: China Defensive Campaign, 4 July 1942-4 May 1945.

- ^ Slim, William. "Chapter IX: The Foundations", Defeat into Victory.

- ^ The thirteen were the C-54/C-46 base at Chabua (1333rd Base Unit); the C-46 bases Tezpur (1327th BU), Misamari (1328th BU), Moran (1331st BU), Mohanbari (1332nd BU), and Sookerating (1337th BU); and the C-87/C-109 bases Jorhat (1330th BU), Shamshernagar (1347th BU), and Kalaikunda (1355th BU) in India; and the C-54 bases Tezgaon (1346th BU), Kurmitola (1345th BU), Lalmanirhat (1326th BU), and Barrackpore (1304th BU) in Bangladesh.

- ^ Yunnanyi (1338th BU), Kunming (1340th BU), Yangkai (1341st BU), Chanyi (1342nd BU), Luliang (1343rd BU), and Loping (1359th BU). As many as ten airfields near Kunming and Chengdu served as China terminals when the B-29 XX Bomber Command was in operation.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 129

- ^ Gann, Ernest, Fate Is The Hunter, New York: Simon & Schuster (1961), ISBN 0-671-63603-0, p. 263.

- ^ Gann 1961, p. 256

- ^ Birdsall 1973, p. 50

- ^ Joe Baugher, private site. Consolidated C-109

- ^ a b c CBI Hump Pilots Association, Flying the Hump: A Fact Sheet for the Hump Operations During World War II

- ^ Gann 1961, pp. 263–264

- ^ a b Ruud Leeuw, private site. Background Information, Curtiss C-46 Commando

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 45

- ^ Gann 1961, pp. 265–271

- ^ Greg Goebel, private site. Curtiss C-46 Commando

- ^ American Aircraft of World War Two, Curtiss Commando

- ^ Birdsall 1973, p. 143

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 79

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 98

- ^ "'Blackie's Gang' Instills Confidence in Air Crews" Hump Express, November 15, 1945.

- ^ Heflin, Dr. Woodrow A (1953). "Chapter 6. Ways and Means", The Army Air Forces in World War II: Volume V, The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945 (Section II, Aid to China: The Theater Air Forces in CBI). University of Chicago Press. p 192.

- ^ "Expended" includes a large number of transports written off ("Class 26 accident") as too expensive or too damaged to warrant repair.

- ^ Tunner 1964, p. 59

External links

- Tunner, Lieutenant General William H. Over the Hump.

- Jon Latimer, Burma: The Forgotten War, London: John Murray, 2004 ISBN 0-7195-6576-6

- Index site for Hump Express, military newspaper of India-China Division, ATC

- Reproduction of Dec. 21, 1944 issue of CBI Round Up (military newspaper), "HUMP SMUGGLING RING EXPOSED BY ARMY"

- USAAF Net: FLYING THE HUMP

- Imphal, The Hump and Beyond (Combat Cargo groups)