Sun Yat-sen: Difference between revisions

→Sun and the overseas Chinese: Bronze statue in Sacramento, California, USA. |

|||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

The old Chinatown in [[Calcutta]] (now known as [[Kolkata]]), [[India]] has a prominent street by the name of Sun Yat Sen Street. |

The old Chinatown in [[Calcutta]] (now known as [[Kolkata]]), [[India]] has a prominent street by the name of Sun Yat Sen Street. |

||

In the United States, |

In the United States, there is a bronze statue of Sun in front of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Sacramento, California. |

||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

Revision as of 02:47, 19 April 2011

Generalissimo Sun Yat-sen 孫文 孫中山 孫逸仙 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Provisional President of the Republic of China | |

| In office 1 January 1912 – 10 March 1912 | |

| Vice President | Li Yuanhong |

| Succeeded by | Yuan Shikai |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 November 1866 Xiangshan, Guangdong, mainland China |

| Died | 12 March 1925 (aged 58) Beijing |

| Political party | Kuomintang |

| Spouse(s) | Lu Muzhen (1885–1915) Kaoru Otsuki (1903-1906) Soong Ching-ling (1915–1925) |

| Children | Sun Fo Sun Yan Sun Wan Fumiko Miyagawa |

| Alma mater | Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese |

| Occupation | Physician Politician Revolutionary Writer |

| Signature | |

Template:ChineseText Sun Yat-sen (12 November 1866 - 12 March 1925)[1] was a Chinese doctor, revolutionary and political leader. As the foremost pioneer of Nationalist China, Sun is frequently referred to as the Founding Father of Republican China, a view agreed upon by both the People's Republic of China[2] and the Republic of China (Taiwan).[3] Sun played an instrumental role in inspiring the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty, the last imperial dynasty of China. Sun was the first provisional president when the Republic of China (ROC) was founded in 1912 and later co-founded the Chinese National People's Party or Kuomintang (KMT) where he served as its first leader.[4] Sun was a uniting figure in post-Imperial China, and remains unique among 20th-century Chinese politicians for being widely revered amongst the people from both sides of the Taiwan Strait.

Although Sun is considered one of the greatest leaders of modern China, his political life was one of constant struggle and frequent exile. After the success of the revolution, he quickly fell out of power in the newly founded Republic of China, and led successive revolutionary governments as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. Sun did not live to see his party consolidate its power over the country during the Northern Expedition. His party, which formed a fragile alliance with the Communists, split into two factions after his death. Sun's chief legacy resides in his developing a political philosophy known as the Three Principles of the People: nationalism, democracy, and the people's livelihood.[5]

Names

The original name of Sun Yat-sen was Sun Wen (孫文) and genealogy name was Sun Deming (孫德明).[1][6] As a child name his milkname was Dixiang (帝象).[1] The courtesy name of Sun Yat-sen was Zaizhi (載之), and his baptized name was Rixin (日新). [7] While schooling in Hong Kong he earned the name Yixian (逸仙).[8] Sun Zhong-shan, the most popular of the Chinese name came from (中山樵), a form of the Japanese name given to him by Miyazaki Touten (宮崎滔天).[1]

Early years

Farm life

Sun Yat-sen was born on 12 November 1866 to a Cantonese family in the village of Cuiheng, Xiangshan (later Zhongshan) county), Guangzhou prefecture, Guangdong province in the Qing China.[1] He was the third son born in family of farmers, and herded cows along with other farming duties at age 6.[1]

Education years

At age 10, Sun Yat-sen began seeking schooling.[1] It is also at this point where he met childhood friend Lu Hao-tung.[1] By age 13 In 1878 after receiving a few years of local schooling, Sun went to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei (孫眉) in Honolulu.[1]

Sun Yat-sen then studied at the ʻIolani School where he learned English, UK history, mathematics, science and Christianity.[1] Originally unable to speak the English language, Sun Yat-sen picked up the language so quickly that he received a prize for outstanding achievement from King David Kalākaua.[9] Sun enrolled in Oahu College (now Punahou School) for further studies for one semester.[10][1] In 1883 he was soon sent home to China as his brother was becoming afraid that Sun Yat-sen would embrace Christianity. [1]

When he returned home in 1883, Sun met up with his childhood friend Lu Hao-tung at Beijidian (北極殿), a temple in Cuiheng Village. [1] They saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (literally North Pole) Emperor-God in the temple, and was dissatisfied with their ancient healing methods.[1] They broke the statue, incurring the wrath of fellow villagers, and escaped to Hong Kong.[1][11][12]

From here, Sun studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary John G. Kerr.[1] Ultimately, he earned the license of Christian practice as a medical doctor from the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of The University of Hong Kong) in 1892.[1][8] Notably, he was one of the first two graduates.[13] He had an arranged marriage with fellow villager Lu Muzhen at age twenty; she bore him a son Sun Fo and two daughters, Sun Jin-yan and Sun Jin-wan.[14]

Christian baptism

Sun was later baptized in Hong Kong by an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States, to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[15][16] Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[16]

Transformation into a revolutionary

During and after the Qing Dynasty rebellion, Sun was a leader within Tiandihui, a secret society that became associated with the rise of triad groups. His activities in Tiandihui brought about much of Sun's back pain. His protégé, Chiang Kai Shek, was also a member of Tiandihui.

Sun, who had grown increasingly frustrated by the conservative Qing government and its refusal to adopt knowledge from the more technologically advanced Western nations, quit his medical practice in order to devote his time to transforming China. At first, Sun aligned himself with the reformists Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao who sought to transform China into a Western-style constitutional monarchy. In 1894, Sun wrote a long letter to Li Hongzhang, the governor-general of Zhili and a reformer in the court, with suggestions on how to strengthen China, but he was rebuffed. Since Sun had never been trained in the classics, the gentry did not accept Sun into their circles. From then on, Sun began to call for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic.

Sun went to Hawaii in October 1894 and founded the Revive China Society to unveil the goal of a prospering China and as the platform for future revolutionary activities. Members were drawn mainly from Cantonese expatriates and from the lower social classes.

In March 1904, Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth,[17] issued by the Territory of Hawaii, stating he was born on November 24, 1870 in Kula, Maui.[18] According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed this certificate to enter the United States at a time when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 would have otherwise blocked him.[19] But on his first attempt in enter the US, he was still arrested.[19] He was later bailed out after 17 days.[19]

The Qing dynasty classified revolutionaries like Sun Yat-sen as bandits.[20]

Sun Yatsen praised the Boxers in the Boxer Rebellion for fighting against Western Imperialism. He said the Boxers were courageous and fearless, fighting to the death against the Western armies, Dr. Sun specifically cited the Battle of Yangcun.[21]

From exile to Wuchang Uprising

In 1895 a coup he plotted failed, and some of his supporters were executed. For the next sixteen years Sun was an exile in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Japan, raising money for his revolutionary party and bankrolling uprisings in China. In 1896 he was detained at the Chinese Legation in London, where diplomats planned to kill him. He was released after twelve days through the efforts of James Cantlie, The Times and the Foreign Office, leaving Sun a hero in Britain.[22]

Sun Yat-sen lived in Japan for about ten years while befriending and being financially aided by a democratic revolutionary in Japan, Miyazaki Toten (1871–1922). In Japan, he was known as Nakayama Shō (Kanji: 中山樵, lit. 'Middle Mountain Woodsman'). Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by a pan-Asian fear of encroaching Western imperialism.[23] In 1905 he joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Japan to form the T’ung-meng Hui (or Tongmeng Hui; Chinese for “Revolutionary Alliance”), which sponsored numerous attempts at uprisings in China and soon became their leader.[24] Nanjing Historical Remains Museum of Chinese Modern History exhibits a bronze statue of Sun and Miyazaki Toten placed alongside each other. Miyazaki wrote a series of articles for newspapers including the nationally circulated Asahi Times about Sun Yat-sen and his revolutionary efforts in China under the title "33-year dream". In Japan, he also met and befriended Mariano Ponce, then a diplomat of the First Philippine Republic. Sun also supported the cause for Philippine Independence and even supplied the Philippine army with guns. Sun Yat-sen eventually left Japan and went to the United States.

On 10 October 1911, a military uprising at Wuchang in which Sun had no direct involvement (at that moment Sun was still in exile and Huang Xing was in charge of the revolution), began a process that ended over two thousand years of imperial rule in China. When he learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, Sun immediately returned to China from the United States. Later, on 29 December 1911 a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanking elected Sun as the provisional President of the Republic of China and set 1 January 1912 as the first day of the First Year of the Republic. This republic calendar system is still used in Taiwan today.

The official history of the Kuomintang (and for that matter, the Communist Party of China) emphasizes Sun's role as the first provisional President, but many historians now question the importance of Sun's role in the 1911 revolution and point out that he had no direct role in the Wuchang uprising and was in fact out of the country at the time. In this interpretation, his naming as the first provisional President was precisely because he was a respected but rather unimportant figure and therefore served as an ideal compromise candidate between the revolutionaries and the conservative gentry.[citation needed]

However, Sun is credited for the funding of the revolutions and for keeping the spirit of revolution alive, even after a series of failed uprisings. Also, as mentioned, he successfully merged minor revolutionary groups to a single larger party, providing a better base for all those who shared the same ideals.

Sun is highly regarded as the National Father of modern China. His political philosophy, known as the Three Principles of People, was proclaimed in August 1905. In his Methods and Strategies of Establishing the Country completed in 1919, he suggested using his Principles to establish ultimate peace, freedom, and equality in the country. He devoted all efforts throughout his whole lifetime until his death for a strong and prosperous China and the well being of its people.

Republic of China

After taking the oath of office, Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces, requesting them to elect and send new senators to establish the National Assembly of the Republic of China. The Assembly then declared the provisional government organizational guidelines and the provisional law of the Republic as the basic law of the nation.

The provisional government was in a very weak position. The southern provinces of China had declared independence from the Qing dynasty, but most of the northern provinces had not. Moreover, the provisional government did not have military forces of its own, and its control over elements of the New Army that had mutinied was limited, and there were still significant forces which had not declared against the Qing.

The major issue before the provisional government was gaining the support of Yuan Shikai, the man in charge of the Beiyang Army, the military of northern China. After Sun promised Yuan the presidency of the new Republic, Yuan sided with the revolution and forced the emperor to abdicate. (Eventually, Yuan proclaimed himself emperor and afterwards opposition snowballed against Yuan's dictatorial methods, leading him to renounce the throne shortly before his death in 1916.) In 1913 Sun led an unsuccessful revolt against Yuan, and he was forced to seek asylum in Japan, where he reorganized the Kuomintang. Sun also supported the bandit leader Bai Lang during the Bai Lang Rebellion. He married Soong Ching-ling, one of the Soong sisters, in Japan on 25 October 1915, without divorcing his first wife Lu Muzhen due to opposition from the Chinese community. Lu pleaded with him to take Soong as a concubine but this was also unacceptable to Sun's Christian ethics.

Sun Yatsen criticized the May Fourth Movement intellectuals for corrupting morals of youth.[25]

Guangzhou militarist government

In the late 1910s, China was greatly divided by different military leaders without a proper central government. Sun saw the danger of this and returned to China in 1917 to advocate unification. He started a self-proclaimed military government in Guangzhou (Canton), Guangdong Province, southern China, in 1921, and was elected as president and Grand Marshal.[26]

Revolutionary and socialist leader Vladimir Lenin praised Dr. Sun Yatsen and the Kuomintang for their ideology and principles. Lenin praised Dr. Sun, his attempts on social reformation and congragulated him for fighting foreign Imperialism.[27][28][29] Dr. Sun also returned the praise, calling him a "great man", and sent his congratulations on the revolution in Russia.[30]

In a February 1923 speech presented to the Students' Union in Hong Kong University, he declared that it was the corruption of China and the peace, order and good government of Hong Kong that turned him into a revolutionary.[31][32] This same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his Three Principles of the People as the foundation of the country and the Five-Yuan Constitution as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the National Anthem of the Republic of China.

To develop the military power needed for the Northern Expedition against the militarists at Beijing, he established the Whampoa Military Academy near Guangzhou, with Chiang Kai-shek as its commandant and with such party leaders as Wang Ching-wei and Hu Han-min as political instructors. The Academy was the most eminent military school of the Republic of China and trained graduates who fought in the Second Sino-Japanese War and on both sides of the Chinese Civil War.

However, as soon as he established his government in Guangzhou, Sun Yat-sen came into conflict with entrenched local power. Sun's militarist government was not based on the Provisional Constitution of 1912, which the anti-Beiyang forces vowed to defend in the Constitutional Protection War. In addition, Sun was elected president by a parliament that did not meet quorum following its move from Beijing. Thus, many politicians and warlords alike challenged the legitimacy of Sun's militarist government. Sun's use of heavy taxes to fund the Northern Expedition to militarily unify China also came at odds with reformers such as Chen Jiongming, who advocated establishing Guangdong as a “model province” before launching a costly military campaign. In sum, Sun's military government was opposed by the internationally recognized Beiyang government in the north, Chen's Guangdong provincial government in the south, and other provincial powers that shifted alliance according to their own benefit.

Path to Northern Expedition

He again became premier of the Kuomintang from 10 October 1919 – 12 March 1925. In the early 1920s Sun received help from the Comintern for his acceptance of Chinese Communist Party members into his Kuomintang. In 1924, in order to hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active cooperation with the Chinese Communists.

By this time, Sun was convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of political tutelage that would culminate in the transition to democracy. Consequently, until his death, Sun prepared for the later Northern Expedition (with help from foreign powers).

On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north and delivered another speech to suggest gathering a conference for the Chinese people and the abolition of all unequal treaties with the Western powers. Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country, despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Although ill at the time, he was still head of the southern government. On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave a speech on Pan-Asianism at Kobe, Japan. He left Guangzhou to hold peace talks with the northern regional leaders on the unification of China. Sun died of liver cancer on 12 March 1925, at the age of 58 at the Rockefeller Hospital in Beijing.[33][34] In keeping with common Chinese practice, his remains were placed in the Green Cloud Monastery, a Buddhist shrine in the Western Hills a few miles outside of Beijing.[35][36]

Legacy

One of Sun's major legacies was his political philosophy, the Three Principles of the People (sanmin zhuyi, 三民主義). These Principles included the principle of democracy (minchuan, 民權), nationalism (minzu, 民族) and welfare (minsheng, 民生). The Principles retained a place in the rhetoric of both the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party with completely different interpretations. This difference in interpretation is due partly to the fact that Sun seemed to hold an ambiguous attitude to both capitalist and communist methods of development, as well as due to his untimely death, in 1925, before he had finished his now-famous lecture series on the Three Principles of the People. In addition, Sun is also one of the primary saints of the Vietnamese religion Cao Dai.

Power struggle

After Sun's death, a power struggle between his young protégé Chiang Kai-shek and his old revolutionary comrade Wang Jingwei split the KMT. At stake in this struggle was the right to lay claim to Sun's ambiguous legacy. In 1927 Chiang Kai-shek married Soong May-ling, a sister of Sun's widow Soong Ching-ling, and subsequently he could claim to be a brother-in-law of Sun. When the Communists and the Kuomintang split in 1927, marking the start of the Chinese Civil War, each group claimed to be his true heirs, a conflict that continued through World War II.

The official veneration of Sun's memory, especially in the Kuomintang, was a virtual cult, which centered around his tomb in Nanking. His widow, Soong Ching-ling, sided with the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and served from 1949 to 1981 as Vice President (or Vice Chairwoman) of the People's Republic of China and as Honorary President shortly before her death in 1981.

Father of the Nation

Sun Yat-sen remains unique among twentieth-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation both in mainland China and in Taiwan. In Taiwan, he is seen as the Father of the Republic of China, and is known by the posthumous name Father of the Nation, Mr. Sun Zhongshan (Chinese: 國父 孫中山先生, where the one-character space is a traditional homage symbol). His likeness is still almost always found in ceremonial locations such as in front of legislatures and classrooms of public schools, from elementary to senior high school, and he continues to appear in new coinage and currency.

Cult of Personality

A personality cult in the Republic of China was centered on Sun and his successor, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chinese Muslim Generals and Imams participated in this cult of personality and One Party state, with Muslim General Ma Bufang making people bow to Dr. Sun's portrait and listen to the national anthem during a Tibetan and Mongol religious ceremony for the Qinghai Lake God.[37] Quotes from the Quran and Hadith were used by Muslims to justify Chiang Kai-shek's rule over China.[38]

Forerunner of the Revolution

On the mainland, Sun is also seen as a Chinese nationalist and proto-socialist, and is highly regarded as the Forerunner of the Revolution (革命先行者). He is mentioned by name in the preamble to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China. In most major Chinese cities one of the main streets is named Zhongshanlu (中山路) to memorialize him, a name even more commonly found than other popular street names such as Renminlu (人民路 The People's Road) and Jiefanglu (解放路 Liberation Road). There are also numerous parks, schools, and geographical features named after him. Xiangshan, his hometown in Guangdong, was re-named Zhongshan in his honor, and there is a hall dedicated to his memory at the Temple of Azure Clouds in Beijing.

In recent years, the leadership of the Communist Party of China has increasingly invoked Sun, partly as a way of bolstering Chinese nationalism in light of Chinese economic reform and partly to increase connections with supporters of the Kuomintang on Taiwan which the PRC sees as allies against Taiwan independence. Sun's tomb was one of the first stops made by the leaders of both the Kuomintang and the People First Party on their trips to mainland China in 2005. A massive portrait of Sun continues to appear in Tiananmen Square for May Day and National Day.

Sun and the overseas Chinese

Sun's notability and popularity extends beyond the Greater China region, particularly to Nanyang (Southeast Asia) where a large concentration of overseas Chinese reside in Singapore and Malaysia. Sun recognised the contributions that the large number of overseas Chinese could make, beyond the sending of remittances to their ancestral homeland. He therefore made multiple visits to spread his revolutionary message to these communities around the world.

Sun made a total of eight visits to Singapore between 1900 and 1911. The first, on 7 September 1900, was to rescue Miyazaki Toten, an ardent Japanese supporter and friend of Sun's, who was arrested there, an act which resulted in his own arrest and a ban from visiting the island for five years. Upon his next visit in June 1905, he met local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock, Tan Chor Nam and Lim Nee Soon in a meeting which was to mark the commencement of direct support from the Nanyang Chinese. Upon hearing their reports on overseas Chinese revolutionists organising themselves in Europe and Japan, he urged them to establish the Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui, which came officially into being on 6 April the following year upon his next visit.

The chapter was housed in a villa known as Wan Qing Yuan (晚晴園)[39] and donated for the use of revolutionalists by Teo. In 1906, the chapter grew in membership to 400, and in 1908, when Sun was in Singapore to escape the Qing government in the wake of the failed Zhennanguan Uprising, the chapter had become the regional headquarters for Tongmenghui branches in Southeast Asia. Sun and his followers travelled from Singapore to Malaya and Indonesia to spread their revolutionary message, by which time the alliance already had over twenty branches with over 3,000 spread round the world.

Sun also took time to establish the United Chinese Library in Singapore, to spread the political philosophy and ideas of Three Principles of the People. It also later disseminated revolutionary ideas and generated support for the 1911 Chinese Revolution against the Manchu rulers. At the height of its existence, the Library served as the de facto headquarters for loyal followers of Sun in Malaya and Singapore. The original site of the United Chinese Library is now gazetted as Heritage Site in Singapore. The present United Chinese Library is now located at Cantonment Road; strategically located opposite the Singapore Police Force's Police Cantonment Complex.

Sun's foresight in tapping the help and resources of the overseas Chinese population was to bear fruit on his subsequent revolutionary efforts. In one particular instance, his personal plea for financial aid at the Penang Conference held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya, helped launch a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula, an effort which helped finance the Second Guangzhou Uprising (also commonly known as the Yellow Flower Mound revolt) in 1911.

The role that overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia played during the 1911 Revolution was so significant that Sun himself recognized "Overseas Chinese as the Mother of the Revolution".

Today, Sun's legacy is remembered in Nanyang at Wan Qing Yuan,[39] which has since been preserved and renamed as the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, and gazetted as a national monument of Singapore on 28 October 1994. The United Chinese Library now served as a literacy society, receiving regular funding from Kuomintang, the Taiwanese government etc. Its members includes 2005 Singapore Cultural Medallion Awardee; notable Singaporean artist Ms Chng Seok Tin.

In Penang, Malaysia, the Penang Philomatic Union which was founded by Sun, its premises at 65 Macalister Road has been preserved as the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Museum.

The old Chinatown in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), India has a prominent street by the name of Sun Yat Sen Street.

In the United States, there is a bronze statue of Sun in front of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Sacramento, California.

Gallery

-

Lu Muzhen (1867-1952), Sun's First wife from 1885 to 1915

-

Sun's second wife, Soong Ching-ling (1893-1981) with Sun in 1924.

-

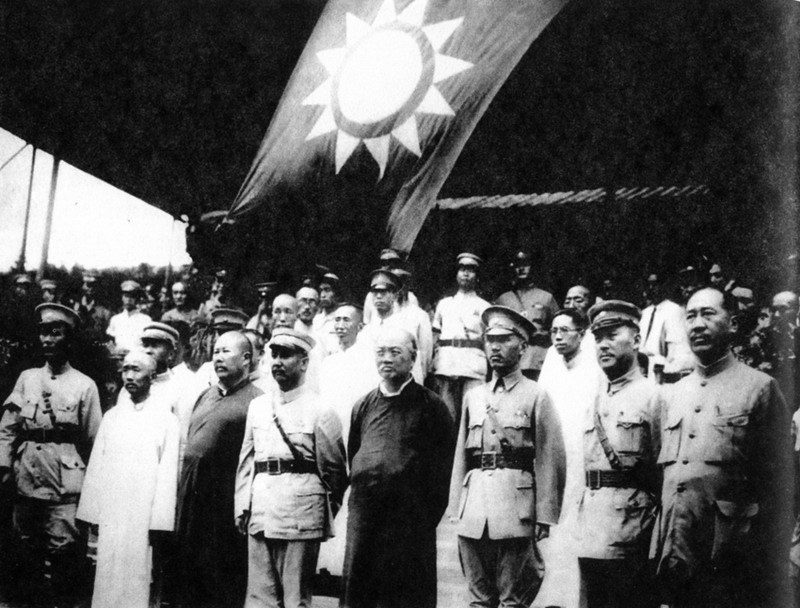

Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek

-

Soong May-ling (宋美齡, 1897-2003). Widow of Chiang Kai-Shek and Sister of Soong Ching-ling. Moved to the United States after Chiang Kai-shek's death.

Memorial colleges

Popular culture

The life of Dr Sun is portrayed in various flims, mainly The Soong Sisters (Chinese 宋家皇朝) and Road to Dawn (Chinese 夜。明). The assassination attempt on Dr. Sun's life was featured in Bodyguards and Assassins (Chinese 十月圍城).

See also

- History of the Republic of China

- Politics of the Republic of China

- Warlord era

- Communist Party of China

- Chinese Nationalism

- Chinese Anarchism

- Sun Yat-sen stamps

Locations:

- Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, in Nanjing

- Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum, in Hong Kong

- Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, in Taipei

- Chung-Shan Building, in Taipei

- Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall

- Sun Yat-sen House (Nanjing)

- Zhongshan Park

- Zhongshan Memorial Middle School

- Sun Yat-sen University, one of the top twenty universities in Mainland China; and National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan.

- Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden, in Vancouver, the largest classical Chinese gardens outside of Asia

- Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park in Chinatown, Honolulu[40]

- He was portrayed by Winston Chao in the 2009 movie The Founding of a Republic.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Singtao daily. Saturday edition. Oct 23, 2010. 特別策劃section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition 民國之父.

- ^ 孙中山尊称“国父”来历, History Study Division of Beijing, China Communist Party

- ^ 中華民國國父孫中山先生, Government Information Office, Republic of China (Taiwan)

- ^ Derek Benjamin Heater. [1987] (1987). Our world this century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199133247, 9780199133246.

- ^ Schoppa, Keith R. [2000] (2000). The Columbia guide to modern Chinese history. Columbia university press. ISBN 0231112769, 9780231112765. p 282.

- ^ 王爾敏. 思想創造時代:孫中山與中華民國. 秀威資訊科技股份有限公司 publishing. ISBN 9862217073, 9789862217078. p 274.

- ^ 王壽南. [2007] (2007). Sun Zhong-san. 臺灣商務印書館 publishing. ISBN 9570521562, 9789570521566. p 23.

- ^ a b 游梓翔. [2006] (2006). 領袖的聲音: 兩岸領導人政治語藝批評, 1906-2006. 五南圖書出版股份有限公司 publishing. ISBN 9571142689, 9789571142685. p 82.

- ^ "Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882)". Iolani School website.

- ^ Brannon, John (2007-08-16). "Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College — now known as Punahou School — for one semester.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ HK university. [2002] (2002). Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years. ISBN 9622096131, 9789622096134.

- ^ Singtao daily. Feb 28, 2011. 特別策劃section A10. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition.

- ^ Bergere, Marie-Claire. Lloyd Janet. [2000] (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford university press. ISBN 0804740119, 9780804740111. p 26.

- ^ a b Soong, (1997) p. 151-178

- ^ Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii www.scribd.com

- ^ Sun Yat-sen’s strong links to Hawaii, Honolulu Star Bulletin "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."

- ^ a b c [http:// sf.worldjournal.com/view/full_sf/12160552/article-孫中山思想-3學者演說精采?instance=top_rec]

- ^ Graham Hutchings (2003). Modern China: A Guide to a Century of Change. Harvard University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0674012402. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Douglas Kerr (2009). Critical Zone 3: A Forum of Chinese and Western Knowledge. Hong Kong University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9622098576. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Contrary to popular legends, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily, but was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him, before returning his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ of habeas corpus because of the Legation's diplomatic immunity, but he began a campaign through The Times. The Foreign Office persuaded the Legation to release Sun through diplomatic channels.

Source: Wong, J.Y. (1986). The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896-1987. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

as summarized in

Clark, David J. (2000). The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 162.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://old.japanfocus.org/_Sato_Kazuo-Sun_Yat_sen_s_1911_Revolution_had_Its_Seeds_in_Tokyo

- ^ http://www.countriesquest.com/asia/china/history/imperial_china/the_manchu_qing_dynasty_1644-1911/internal_threats.htm

- ^ Joseph T. Chen (1971). The May fourth movement in Shanghai: the making of a social movement in modern China. Brill Archive. p. 13. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Linda Pomerantz-Zhang (1992). Wu Tingfang (1842-1922): reform and modernization in modern Chinese history. Hong Kong University Press. p. 255. ISBN 962209287X. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ^ Robert Payne (2008). Mao Tse-Tung Ruler of Red China. READ BOOKS. p. 22. ISBN 1443725218. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Great Soviet Encyclopedia. p. 237. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982). Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25. Macmillan. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Bernice A Verbyla (2010). Aunt Mae's China. Xulon Press. p. 170. ISBN 1609574567. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Ho, Virgil K.Y. [2005] (2005). Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928271-4

- ^ Carroll, John Mark. Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01701-3

- ^ "Lost Leader". Time (magazine). 23 March 1925. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

A year ago his death was prematurely announced; but it was not until last January that he was taken to the Rockefeller Hospital at Peking and declared to be in the advanced stages of cancer of the liver.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dr. Sun Yat-sen Dies in Peking. Chinese Leader Had Failed Steadily Since an Operation ? on Jan. 26 for Cancer. Helped To Oust Manchus. Headed the New Government for a Time". New York Times. 12 March 1925.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Leinwand, Gerald (2002). 1927: High Tide of the 1920's. Basic Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-56858-245-0. Google Book Search. Retrieved on September 14, 2009.

- ^ Dr Yat-Sen Sun at Find a Grave

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 0742511448. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Stéphane A. Dudoignon, Hisao Komatsu, Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 134. ISBN 00415368359. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall". Wanqingyuan.com.sg. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ^ "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". The City and County of Honolulu. November 12, 2007. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

Further reading

- Soong, Irma Tam (1997). Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i. Hawai'i: The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 31.

- Sun Yat-sen's vision for China / Martin, Bernard, 1966.

- Sun Yat-sen, Yang Chu-yun, and the early revolutionary movement in China / Hsueh, Chun-tu

- Sun Yat-sen / Bergere, Marie-Claire. c. 1998.

- Sun Yat-sen 1866-1925 / The Millennium Biographies / Hong Kong, 1999

- Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the Chinese revolution Schiffrin, Harold Z. /1968.

- Sun Yat-sen; his life and its meaning; a critical biography. Sharman, Lyon, / 1968, c. 1934

- "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang memorial hall". Retrieved 2005-07-01.

- "Doctor Sun Yat Sen memorial hall". Retrieved 2005-07-01.

- "A detailed talk about Sun Zhongshan" (in Chinese). Retrieved September 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Japanese activist Miyazaki Toten a middleman and financier for Sun Yat-sen".

- "Toten Miyazaki bio".

- The Man Who Changed China / Buck, Pearl, 1953.

External links

- ROC Government Biography

- Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Contemporary views of Sun among overseas Chinese

- Yokohama Overseas Chinese School established by Dr. Sun Yat-sen

- National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall Official Website

- Dr. Sun Yat Sen Middle School 131, New York City

- Dr. Sun Yat Sen Museum, Penang, Malaysia

- Was Yung Wing Dr. Sun's supporter? The Red Dragon scheme reveals the truth!

- Miyazaki Toten He devoted his life and energy to the Chinese people.

- Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall A place to commemorate Sun Yat-sen in Guangzhou

- MY GRANDFATHER, DR. SUN YAT-SEN - By Lily Sui-fong Sun

- 浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 - 我的祖父是客家人

- Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Foundation of Hawaii A virtual library on Dr. Sun in Hawaii including sources for six visits

- Who is Homer Lea? Sun's best friend. He trained Chinese soldiers and prepared the frame work for the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

- 1866 births

- 1925 deaths

- Presidents of the Republic of China

- Chinese revolutionaries

- Chinese Christians

- Chinese philosophers

- 19th-century philosophers

- 20th-century philosophers

- Cao Dai saints

- Chinese Congregationalists

- Deaths from liver cancer

- Cancer deaths in China

- People from Zhongshan

- People of the Xinhai Revolution

- Family of Sun Yat-sen

- Georgists

- Democratic socialists

- Iolani School alumni

- Punahou School alumni

- Alumni of the University of Hong Kong

- National anthem writers

- Republic of China politicians from Guangdong

- Chinese Hakka people

- Generalissimos

- Chinese Nationalist heads of state

- Triad members

- American people of Chinese descent

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Chinese socialists

- Marshals of China