Éric Rohmer: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.2) (Robot: Adding eu:Éric Rohmer |

→Biography: A bit more info on the very early part of Rohmer's career |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

=== Career === |

=== Career === |

||

Rohmer originally began his career as a teacher,<ref name="Film-maker Rohmer dies in Paris"/>, while also working as a newspaper journalist.<ref name="French filmmaker Eric Rohmer dies at 89"/> Under the pseudonym '''Gilbert Cordier''', he published a novel, ''Elisabeth'', a novel, in 1946.<ref name="French filmmaker Eric Rohmer dies at 89"/> |

|||

In 1950, he co-founded ''La Gazette du Cinéma''. In 1951, Rohmer shot the short film ''Présentation ou Charlotte et son steak'', co-starring a young [[Jean-Luc Godard]] (however, the film was not completed until 1961). Soon thereafter, Rohmer joined the staff of the newly-founded film magazine ''[[Cahiers du Cinema]]'', of which he would eventually become the editor.<ref name="Film-maker Rohmer dies in Paris"/><ref name="Neupert2007">{{cite book |

|||

| last = Neupert |

| last = Neupert |

||

| first = Richard John |

| first = Richard John |

||

| Line 33: | Line 35: | ||

| isbn = 9780299217044 |

| isbn = 9780299217044 |

||

| page = 29 |

| page = 29 |

||

| quote = Eric Rohmer, who began writing for Cahiers at age thirty-one}}</ref> There, Rohmer established himself as a critic with a distinctive voice; fellow ''Cahiers du Cinema'' contributor and [[French New Wave]] filmmaker [[Luc Moullet]] later remarked that, unlike the the more aggressive and personal writings of younger critics like [[Francois Truffaut]] and [[Jean-Luc Godard]], Rohmer favored a [[rhetoric|rhetorical]] style that made extensive use of questions and rarely used the [[first person singular]]. <ref name="mask">Moullet, Luc. [http://mubi.com/notebook/posts/the-mask-and-the-role-of-god The Mask and the Role of God.] [[Mubi (website)|Mubi Notebook]].</ref> |

|||

| quote = Eric Rohmer, who began writing for Cahiers at age thirty-one}}</ref> |

|||

With [[Claude Chabrol]], Rohmer co-wrote a study of [[Alfred Hitchcock]], ''Hitchcock'' (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1957), which focused on Hitchcock's [[Roman Catholic]] background and is described as "one of the most influential film books since the Second World War, casting new light on a film-maker hitherto considered a mere entertainer".<ref name="Telegraph1"/> |

With [[Claude Chabrol]], Rohmer co-wrote a study of [[Alfred Hitchcock]], ''Hitchcock'' (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1957), which focused on Hitchcock's [[Roman Catholic]] background and is described as "one of the most influential film books since the Second World War, casting new light on a film-maker hitherto considered a mere entertainer".<ref name="Telegraph1"/> |

||

Revision as of 00:04, 4 January 2012

Éric Rohmer | |

|---|---|

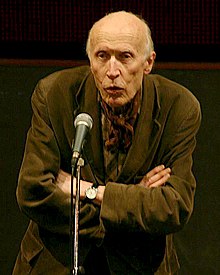

Rohmer at the Cinémathèque Française in 2004 | |

| Born | Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer or Jean Marie Maurice Schérer 20 March 1920 |

| Died | 11 January 2010 (aged 89) |

| Occupation | Film Director |

| Years active | 1950–2010 |

Éric Rohmer (French: [eʁik ʁomɛʁ]; 1920–2010) was a French film director, film critic, journalist, novelist, screenwriter and teacher. A figure in the post-war New Wave cinema, he was a former editor of Cahiers du cinéma.

Rohmer was the last of the French New Wave directors to become established. He worked as the editor of the Cahiers du cinéma periodical from 1957 to 1963, while most of his Cahiers colleagues – among them Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut – were beginning their careers and gaining international attention. René Schérer, a philosopher, is his brother and René Monzat, a journalist, is his son.

Rohmer came to international attention around 1969 when his film Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's) was nominated at the Academy Awards.[1] He won the San Sebastián International Film Festival with Claire's Knee in 1971. In 2001, Rohmer received the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. His works were viewed by audiences around the world. He died of unspecified causes on 11 January 2010. In his obituary in The Daily Telegraph he was described as "the most durable film-maker of the French New Wave", outlasting his peers and "still making movies the public wanted to see" late in his career.[2]

Biography

Early life

Rohmer was born Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer (or Jean-Marie Maurice Schérer)[3] in Tulle in south central France, the son of Mathilde (née Bucher) and Lucien Scherer.[4] Rohmer was a Roman Catholic.[2][5] He fashioned his pseudonym from the names of two famous artists: actor and director Erich von Stroheim and writer Sax Rohmer, author of the Fu Manchu series.[6]

Career

Rohmer originally began his career as a teacher,[7], while also working as a newspaper journalist.[6] Under the pseudonym Gilbert Cordier, he published a novel, Elisabeth, a novel, in 1946.[6]

In 1950, he co-founded La Gazette du Cinéma. In 1951, Rohmer shot the short film Présentation ou Charlotte et son steak, co-starring a young Jean-Luc Godard (however, the film was not completed until 1961). Soon thereafter, Rohmer joined the staff of the newly-founded film magazine Cahiers du Cinema, of which he would eventually become the editor.[7][8] There, Rohmer established himself as a critic with a distinctive voice; fellow Cahiers du Cinema contributor and French New Wave filmmaker Luc Moullet later remarked that, unlike the the more aggressive and personal writings of younger critics like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, Rohmer favored a rhetorical style that made extensive use of questions and rarely used the first person singular. [9]

With Claude Chabrol, Rohmer co-wrote a study of Alfred Hitchcock, Hitchcock (Paris: Éditions Universitaires, 1957), which focused on Hitchcock's Roman Catholic background and is described as "one of the most influential film books since the Second World War, casting new light on a film-maker hitherto considered a mere entertainer".[2]

In 1957, Rohmer was married to Thérèse Barbet.[2] The couple had two sons.[2]

Chabrol produced Rohmer's directorial debut, Le signe du lion in 1959 to little notice. In 1963 Barbet Schroeder founded the production company Les Films du Losange which produced all of Rohmer's work (except his last three features produced by La Compagnie Eric Rohmer).[10] Rohmer's career began to gain momentum with his cycle of films Six Moral Tales. Each tale follows the same story, inspired by F. W. Murnau's Sunrise (1927) — a man, married or otherwise committed to a woman is tempted by a second woman but resists. The first La boulangère de Monceau lasts 23 minutes, the second La Carrière de Suzanne 55 minutes, the remainder are feature-length. The third (Ma nuit chez Maud) and the fifth (Le Genou de Claire) films in the series brought him international recognition. The third (the fourth to be shot), Ma nuit chez Maud (1969), received Oscar nominations for best screenplay and best foreign film,[6][7][11] while the following film Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee, 1971) won the San Sebastián International Film Festival.[7]

Later professional life

Following the Moral Tales Rohmer made two period films — La Marquise d'O... (1976) from a novella by Heinrich von Kleist and Perceval le Gallois (1978), based on a 12th century manuscript by Chrétien de Troyes. Rohmer was a highly literary man. His films frequently refer to ideas and themes in plays and novels, such as references to Jules Verne (in The Green Ray), William Shakespeare (in A Winter's Tale) and Pascal's Wager (in Ma nuit chez Maud).

Rohmer embarked on a second series, the Comedies and Proverbs, each based on a proverb. He followed these with a third series in the 1990s: Tales of the Four Seasons. Conte d’Automne or Autumn Tale was a critically acclaimed release in 1999 when Rohmer was 79.[7]

Beginning in the 2000s, Rohmer, in his eighties returned to period drama with The Lady and the Duke and Triple Agent. The Lady and the Duke caused considerable controversy in France, where its negative portrayal of the French Revolution led some critics to label it monarchist propaganda. Its innovative cinematic style and strong acting performances led it to be well-received elsewhere.

In 2001, his life's work was recognised when he received the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.[12][13]

In 2007, Rohmer's final film, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, was shown during the Venice Film Festival,[12] at which he spoke of retiring.[7][12]

Death

Rohmer died on the morning of 11 January 2010 at the age of 89.[7][12][13] His cause of death is unknown.[12][13] He had been admitted to hospital the previous week.[11]

The former Culture Minister Jack Lang said he was "one of the masters of French cinema".[12] Director Thierry Fremaux described his work as "unique".[12]

The grave of Eric Rohmer (Maurice Scherer) is located at the 13 district of Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

During the 2010 César Awards, actor Fabrice Luchini presented a special tribute to him:

I’m gonna read a remarkable text written by Jacques Fieschi: "Writer, director; creator of “the cinematographe”, challenger of "Les cahiers du cinema", which recently published a special edition on Eric Rohmer. Truffaut once said he was one of the greatest directors of the 20th century, Godard was his brother, Chabrol admired him, Wenders couldn’t stop taking photos of him. Rohmer is a tremendous international star. The one and only French director who was in coherence with the money spent on his films and the money that his films made. I remember a phrase by Daniel Toscan Du Plantier the day “Les Visiteurs” opened, which eventually sold 15 million tickets: “Yes but there is this incredible film called "L'arbre, le maire et la médiathèque" that sold 100,000 tickets, which may sound ridiculous in comparison, but no, because but it was only playing in one theater for an entire year." A happy time for cinema when this kind of thing could happen. Rohmer." Here is a tribute from Jacques Fieschi: "We are all connected with the cinema, at least for a short time. The cinema has its economical laws, its artistic laws, a craft that once in a while rewards us or forgets us. Eric Rohmer seems to have escaped from this reality by inventing his own laws, his own rules of the game. One could say his own economy of the cinema that served his own purpose, which could skip the others, or to be more accurate that couldn’t skip the audience with its originality. He had a very unique point of view on the different levels of language and on desire that is at work in the heart of each and every human being, on youth, on seasons, on literature, of course, and one could say on history. Eric Rohmer, this sensual intellectual, with his silhouette of a teacher and a walker. As an outsider he made luminous and candid films in which he deliberately forgot his perfect knowledge of the cinema in a very direct link with the beauty of the world." The text was by Jacques Fieschi and it was a tribute to Eric Rohmer, Thank You.

On February 8, 2010 the Cinémathèque Française held a special tribute to Rohmer which included a screening of Claire's Knee and a short video tribute to Rohmer by Jean-Luc Godard.[14]

Rohmer's style

Rohmer's films concentrate on intelligent, articulate protagonists who frequently fail to own up to their desires. The contrast between what they say and what they do fuels much of the drama in his films.

Rohmer saw the full-face closeup as a device which does not reflect how we see each other and avoided its use. He avoids extradiegetic music (not coming from onscreen sound sources), seeing it as a violation of the fourth wall. He has on occasion departed from this rule, inserting soundtrack music in places in The Green Ray (1986) (released as Summer in the United States). Rohmer also tends to spend considerable time in his films showing his characters going from place to place, walking, driving, bicycling or commuting on a train, engaging the viewer in the idea that part of the day of each individual involves quotidian travel. This was most evident in [Le Beau mariage] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (1982), which had the female protagonist constantly traveling, particularly between Paris and Le Mans.

Rohmer typically populates his movies with people in their twenties and the settings are often on beautiful beaches and resorts, notably in La Collectionneuse (1967), Pauline at the Beach (1983), The Green Ray (1986) and A Summer's Tale (1996). These films are immersed in an environment of bright sunlight, blue skies, green grass, sandy beaches, and clear waters.

The director's characters engage in long conversations—mostly talking about man-woman relationships but also on mundane issues like trying to find a vacation spot. There are also occasional digressions by the characters on literature and philosophy as most of Rohmer's characters are middle class and university educated.

A Summer's Tale (1996) has most of the elements of a typical Rohmer film: no soundtrack music, no closeups, a seaside resort, long conversations between beautiful young people (who are middle class and educated) and discussions involving the characters' interests from songwriting to ethnology.

He described his work as follows:

You can say that my work is closer to the novel - to a certain classic style of novel which the cinema is now taking over - than to other forms of entertainment, like the theatre.[7]

Rohmer said he wanted to look at "thoughts rather than actions", dealing "less with what people do than what is going on in their minds while they are doing it."

His style was famously criticised by Gene Hackman's character in the 1975 film Night Moves who describes viewing Rohmer's films as "kind of like watching paint dry".[7]

Awards and nominations

The Venice Film Festival awarded Éric Rohmer the Career Golden Lion in 2001.

- La Collectionneuse (1967)

- Berlin Film Festival Silver Bear Winner - Special Prize of the Jury[15]

- Berlin Film Festival Youth Award Film Winner

- Ma nuit chez Maud (1969)

- Cannes Film Festival Official Selection[16]

- 42nd Academy Awards Best Foreign Language Film Nominee[1]

- 43rd Academy Awards Best Original Screenplay Nominee

- La Marquise d'O... (1976)

- Pauline à la plage (1983)

- Berlin Film Festival Silver Bear for Best Director[17]

- Berlin Film Festival OCIC Award Winner - Honorable Mention

- Berlin Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize Winner - Competition

- Le Rayon vert (1986)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Lion Winner

- Venice Film Festival FIPRESCI Prize Winner

- Conte d'hiver (1992)

- Berlin Film Festival[18] FIPRESCI Prize Winner - Competition

- Berlin Film Festival Prize of the Ecumenical Jury Winner - Special Mention - Competition

- Conte d'automne (1998)

- Venice Film Festival Golden Osella Winner - Best Original Screenplay

- Venice Film Festival Sergio Trasatti Award - Special Mention

- Triple Agent (2004)

- Berlin Film Festival Official Selection

Filmography

Contes moraux (Six Moral Tales)

- 1963 #1 La Boulangère de Monceau (The Bakery Girl of Monceau) — short, not released theatrically

- 1963 #2 La Carrière de Suzanne (Suzanne's Career) — short, not released theatrically

- 1967 #4 La Collectionneuse (The Collector)

- 1969 #3 Ma nuit chez Maud (My Night at Maud's) — although planned as the third moral tale, its production was delayed due to the unavailability of actor Jean-Louis Trintignant. It was released after the fourth tale.

- 1970 #5 Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee)

- 1972 #6 L'Amour l'après-midi (Love in the Afternoon/Chloe in the Afternoon)

Comédies et Proverbes (Comedies and Proverbs)

- 1981 La Femme de l'aviateur (The Aviator's Wife) — "It is impossible to think about nothing."

- 1982 Le Beau mariage (A Good Marriage) — "Can anyone refrain from building castles in Spain?"

- 1983 Pauline à la plage (Pauline at the Beach) — "He who talks too much will hurt himself."

- 1984 Les Nuits de la pleine lune (Full Moon in Paris) — "He who has two women loses his soul, he who has two houses loses his mind."

- 1986 Le Rayon vert (The Green Ray/Summer) — "Ah, for the days/that set our hearts ablaze,"

- 1987 L'Ami de mon amie (My Girlfriend's Boyfriend/Boyfriends and Girlfriends) — "My friends' friends are my friends."

Contes des quatre saisons (Tales of the Four Seasons)

- 1990 Conte de printemps (A Tale of Springtime)

- 1992 Conte d'hiver (A Winter's Tale/A Tale of Winter)

- 1996 Conte d'été (A Tale of Summer)

- 1998 Conte d'automne (A Tale of Autumn)

Other feature films

- 1959 Le Signe du lion

- 1976 La Marquise d'O... (The Marquise of O...)

- 1978 Perceval le Gallois

- 1980 Catherine de Heilbronn

- 1987 Le trio en si bémol

- 1987 Quatre Aventures de Reinette et Mirabelle (Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle)

- 1993 L'Arbre, le maire et la médiathèque (The Tree, The Mayor, and the Mediatheque)

- 1995 Les Rendez-vous de Paris (Rendezvous in Paris)

- 2000 L'Anglaise et le duc (The Lady and the Duke)

- 2004 Triple Agent

- 2007 Les Amours d'Astrée et de Céladon

Other short films

- 1950 Journal d'un scélérat

- 1952 Les Petites filles modèles (unfinished)

- 1954 Bérénice

- 1956 La Sonate à Kreutzer

- 1958 Véronique et son cancre

- 1960 Présentation ou Charlotte et son steak

- 1963 see above, Contes moraux (Six Moral Tales)

- 1964 Nadja à Paris

- 1965 "Place de l'Étoile" from Paris vu par... (Six in Paris)

- 1966 Une Étudiante d'aujourd'hui

- 1983 Loup y es-tu? (Wolf, Are You There?)

- 1986 Bois ton café (Drink your coffee it's getting cold!) (music video)

- 1997 Fermière à Montfaucon

- 1997 Un dentiste exemplaire

- 1999 Une histoire qui se dessine

- 1999 La Cambrure directed by Edwige Shaki with Eric Rohmer's help

- 2004 Le canapé rouge

Works for television

Episodes for En profil dans le texte

- 1963 Paysages urbains

- 1964 Les cabinets de physique, la vie de société au XVIIIe siècle

- 1964 Les métamorphoses du paysage, l'ère industrielle

- 1964 Les salons de Diderot

- 1964 Perceval ou le conte du Graal

- 1965 Don Quichotte de Cervantes

- 1965 Les histoires extraordinaires d'Edgar Poe

- 1965 Les caractères de La Bruyère

- 1965 Entretien sur Pascal

- 1966 Victor Hugo, les contemplations

- 1968 Entretien avec Mallarmé

- 1968 Nancy au XVIIIe siècle

- 1969 Victor Hugo architecte

- 1969 La sorcière de Michelet

- 1969 Le béton dans la ville

- 1970 Le français langue vivante?

Episodes for Cinéastes de notre temps

- 1965 Carl Th. Dreyer

- 1966 Le celluloïd et le marbre

Episodes for Aller au cinéma

- 1968 Post-face à l'Atalante

- 1968 Louis Lumière

- 1968 Post-face à Boudu sauvé des eaux

Ville nouvelle (1975, four-part miniseries)

- Épisode 1: L'enfance d'une ville

- Épisode 2: La diversité du paysage urbain

- Épisode 3: La forme de la ville

- Épisode 4: Le logement à la demande

Episode for Histoire de la vie privée

- 1989 Les Jeux de société

non-series

- 1967 L'homme et la machine

- 1967 L'homme et les images

- 1968 L'homme et les frontières

- 1968 L'homme et les gouvernements

References

- ^ a b "The 42nd Academy Awards (1970) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e "Eric Rohmer". The Daily Telegraph. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dave Kehr "Eric Rohmer, a Leading Filmmaker of the French New Wave, Dies at 89", New York Times, 11 January 2010

- ^ Eric Rohmer Biography (1920?-), Film Reference

- ^ The religion of director Eric Rohmer, Adherents.com

- ^ a b c d "French filmmaker Eric Rohmer dies at 89". CBC News. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ruadhán Mac Cormaic (2010-01-11). "Film-maker Rohmer dies in Paris". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Neupert, Richard John (19 February 2007). A history of the French new wave cinema. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780299217044. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

Eric Rohmer, who began writing for Cahiers at age thirty-one

- ^ Moullet, Luc. The Mask and the Role of God. Mubi Notebook.

- ^ Agnès Poirier "Eric Rohmer: un hommage", The Guardian, 12 January 2010

- ^ a b "French film maker Rohmer dies at 89". Philippine Daily Enquirer. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g "French film-maker Eric Rohmer dies". BBC. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ a b c "French director Eric Rohmer dies". The New Zealand Herald. 2010-01-12. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) [dead link] - ^ Godard on the Death of Róhmer, Cinemasparagus blog

- ^ "Berlinale 1967: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: My Night at Maud's". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1983 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1992 Programme". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

Bibliography

- Montero, José Francisco & Paredes, Israel. Imágenes de la Revolución. La inglesa y el duque/La commune (París, 1871). 2011. Shangrila Ediciones. http://shangrilaedicionesblog.blogspot.com/2011/10/imagenes-de-la-revolucion-intertextos.html

External links

- Éric Rohmer at IMDb

- extensive biography of Eric Rohmer

- Éric Rohmer at AlloCiné (in French)

- Éric Rohmer — critical essay at Kamera

- Interview with 'The French Revolutionary - Eric Rohmer

- Tom Milne Obituary: Eric Rohmer, The Guardian, 11 January 2010

- Christopher Hawtree "Eric Rohmer: Prolific film-maker, critic and novelist whose pioneering work homed in on romantic tangles", The Independent, 13 January 2010

- "Eric Rohmer: director whose films included Le genou de Claire", The Times, 12 January 2010

- "On Eric Rohmer" in memoriam from n+1

- "The Grave of Eric Rohmer (Maurice Scherer), Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris.",.