Aksai Chin: Difference between revisions

m Removing "Map_of_Kashmir_published_by_The_Survey_Of_India.jpg", it has been deleted from Commons by Fastily because: No license since 1 January 2012. |

|||

| Line 119: | Line 119: | ||

==Strategic importance== |

==Strategic importance== |

||

[[China National Highway 219]] runs through Aksai Chin connecting [[Lhazê County|Lazi]] and [[Xinjiang]] in the [[Tibet Autonomous Region]]. Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects the |

[[China National Highway 219]] runs through Aksai Chin connecting [[Lhazê County|Lazi]] and [[Xinjiang]] in the [[Tibet Autonomous Region]]. Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects the Tibet and Xinjiang. Construction started in 1951 and the road was completed in 1957. The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the [[Sino-Indian War]] of 1962.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} |

||

==Chinese terrain model== |

==Chinese terrain model== |

||

Revision as of 03:23, 10 January 2012

35°7′N 79°8′E / 35.117°N 79.133°E

Aksai Chin (Hindi: अक्साई चिन; Urdu: اکسائی چن; Chinese: 阿克赛钦; pinyin: Ākèsàiqīn) is one of the two main disputed border areas between China and India, and the other is the area in the Assam Himalaya which the Chinese call South Tibet, which comprises most of India's Arunachal Pradesh. It is administered by China as part of Hotan County in the Hotan Prefecture of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, but is also claimed by India as a part of the Ladakh district of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. What little evidence exists suggests that the few true locals in Aksai Chin have Buddhist beliefs. Place names like inter alia Sumnal, Palong Karpo , Thaldat, Sumgal, Nischu, Sumna, Sumdo in Aksai Chin are all place names in Aksai Chin of Ladakhi or Tibetan origin. In 1962 China and India fought a brief war over Aksai Chin and Parts of Arunachal Pradesh, and the Parliament of India on November 14, 1962 passed a unanimous resolution vowing to recover every inch of land occupied by China “howsoever long or hard the struggle may be” which remains to be fulfilled. In 1993 and 1996 the two countries signed agreements to respect the Line of Actual Control.[1]

Name

The etymology of Aksai Chin is uncertain regarding the word "Chin". As a word of Turk origin, aksai literally means "white brook" but whether the word Chin refers to Chinese or pass is disputed. The area is largely a vast high-altitude desert including some salt lakes from 4,800 metres (15,700 ft) to 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) above sea level. It covers an area of 37,244 square kilometres (14,380 sq mi). The Chinese name of the region, 阿克赛钦, is composed of Chinese characters chosen for their phonetic values,[2] irrespective of their meaning.

Geography

Aksai Chin is one of the two main disputed border areas between India and China. India claims Aksai Chin as the eastern-most part of the Jammu and Kashmir state. The line that separates Indian-administered areas of Jammu and Kashmir from Aksai Chin is known as the Cease Fire Line or Line of Actual Control (LAC) and is concurrent with the Chinese Aksai Chin claim line.

Topographically, Aksai Chin is a high altitude desert. In the southwest, the Karakoram range form the Line of Actual Control between Aksai Chin and rest of Ladakh to the east. Glaciated peaks in the mid portion of this line of actual control reach heights of 6,950 metres (22,800 ft).

In the north, the Kunlun Range separates Aksai Chin from the Tarim Basin, where Khotan is situated. According to a recent detailed Chinese map, no roads cross the Kunlun Range within Hotan Prefecture, and only one track does so, over the Hindutash Pass.[3] The Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890 gives a description and details of places inside Kashmir and thus ipso facto also includes a description of the Híñdutásh Pass in north eastern Kashmir in the Aksai Chin area in Kashmir . The aforesaid Gazetteer states in pages 520 and 364 that “The eastern (Kuenlun) range forms the southern boundary of Khotan”, “and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Diwan, .... and the Hindutak (i.e. Híñdutásh ) Díwán”. The aforesaid Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák describes Khotan as “ A province of the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák[4]”.

The northern part of Aksai Chin is referred to as the Soda Plain and contains Aksai Chin's largest river, the Karakash River, the Gomati river of classical Kashmir, which receives meltwater from a number of glaciers, crosses the Kunlun farther northwest, in Pishan County and enters the Tarim Basin, where it serves as one of the main sources of water for Karakax and Hotan Counties.

The eastern part of the region contains several small endorheic basins. The largest of them is that of the Aksai Chin Lake, which is fed by the river of the same name.

The region is almost uninhabited, has no permanent settlements, and receives little precipitation as the Himalayas and the Karakoram block the rains from the Indian monsoon.

History

Aksai Chin was historically part of the Himalayan Kingdom of Ladakh until Ladakh was annexed from the rule of the local Namgyal dynasty by the Dogras and the princely state of Kashmir in the 19th century. It was subsequently absorbed into British India. One of the main causes of the Sino-Indian War of 1962 was India's discovery of a road China had built through the region, which is historically part of Ladakh. According to Rolf Alfred Stein author of Tibetan Civilization, the area of Shang Shung was not historically a part of Tibet and was a distinctly foreign territory to the Tibetans. According to Rolf Alfred Stein[5],

" “…Then further west, The Tibetans encountered a distinctly foreign nation. - Shangshung, with its capital at Khyunglung. Mt. Kailāśa (Tise ) and Lake Manasarovar formed part of this country., whose language has come down to us through early documents. Though still unidentified, it seems to be Indo European. …Geographically the country was certainly open to India, both through Nepal and by way of Kashmir and Ladakh. Kailāśa is a holy place for the Indians, who make pilgrimages to it. No one knows how long they have done so, but the cult may well go back to the times when Shangshung was still independent of Tibet. How far Shangshung stretched to the north , east and west is a mystery…. We have already had an occasion to remark that Shangshung, embracing Kailāśa sacred Mount of the Hindus, may once have had a religion largely borrowed from Hinduism. The situation may even have lasted for quite a long time. In fact, about 950, the Hindu King of Kabul had a statue of Vişņu, of the Kashmiri type (with three heads), which he claimed had been given him by the king of the Bhota (Tibetans) who, in turn had obtained it from Kailāśa.”

A chronicle of Ladakh compiled in the 17th century called the La dvags rgyal rabs, meaning the Royal Chronicle of the Kings of Ladakh recorded that this boundary was traditional and well-known. The first part of the Chronicle was written in the years 1610 -1640, and the second half towards the end of the 17th century. The work has been translated into English by A. H. Francke and published in 1926 in Calcutta titled the “Antiquities of Indian Tibet” . In volume 2, the Ladakhi Chronicle describes the partition by King Sykid-Ida-ngeema-gon of his kingdom between his three sons, and then the chronicle described the extent of territory secured by that son. The following quotation is from page 94 of this book:

" "He gave to each of his sons a separate kingdom, viz., to the eldest Dpal-gyi-ngon, Maryul of Mnah-ris, the inhabitants using black bows; ru-thogs of the east and the Gold-mine of Hgog; nearer this way Lde-mchog-dkar-po; at the frontier ra-ba-dmar-po; Wam-le, to the top of the pass of the Yi-mig rock…..”

From a perusal of the aforesaid work, It is obvious and evident that Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh and even after the family partition, Rudokh continued to be part of Ladakh. Maryul meaning lowlands was a name given to a part of Ladakh. Even at that time, i.e. in the 10th century, Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh and Lde-mchog-dkar-po, i.e. Demchok was also an integral part of Ladakh.

At an elevation of 5,000m, the desolation of Aksai Chin had no human importance other than an ancient trade route that crossed over it, providing a brief pass during summer for caravans of yaks between Xinjiang and Tibet.[6] The Aksai Chin area was traversed in 1865 by W. H. Johnson , Civil Assistant of the Trigonometrical Survey of India of the Survey of India. In July 1865, he was instructed to explore the country of Khotan. “He followed the familiar route from Leh as far as Kyam, and then broke news ground by marching in a northern direction. He travelled through NIschu, Huzakhar, and Yangpa, describuing these isolated places in the Aksai Chin in great detail. He was the first European to cross the Yangi Diwan Pass between Tash and Khushlashlangar, and to take a route which Juma Khan, ambassador from Khotan to the British Government, had travelled some time before. He waited at the source of the Kara Kash for someone to receive him at the first village on the northern side of the Kuen Lun. On the twelfth day his patience was rewarded; a bearer came from the Badsha of Khotan saying ‘he had dispatched his wazeer, Sarfulla Khoja, to meet me at Bringja, the first encampment beyond the Ladakh boundary, for the purpose of escorting me to Khotan. Three miles from Khotan, Khan’s two sons were waiting to welcome him. The Khan had a great deal to say. Four years before he had visited Mecca and on his return he was made the chief Kasi of Khotan. ‘Within a month,’ he said ‘he succeeded in raising a rebellion against the Chinese, which resulted in their massacre, and his election by the inhabitants of the country to be their Khan Badsha or ruler.’ When the Chinese were defeated in Khotan, Yarkand, Kashgar, and other places in Central Asia, Yaqub Beg set up an independent Muslim country which survived until 1877 when the Chinese troops recaptured Kashgar”. W.H. Johnson’s survey established certain important points. "Brinjga was in his view the boundary post" ( near the Karanghu Tagh Peak in the Kuen Lun in Ladakh ), thus implying "that the boundary lay along the Kuen Lun Range"[7]. Johnson’s findings demonstrated that the whole of the Kara Kash valley was “ within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir” and an integral part of the territory of Kashmir . "He noted where the Chinese boundary post was accepted. At Yangi Langar, three marches from Khotan , he noticed that there were a few fruit trees at this place which originally was a post or guard house of the Chinese". “The Khan wrote Johnson ‘that he had dispatched his Wazier, Saifulla Khoja to meet me at Bringja, the first encampment beyond the Ladakh boundary for the purpose of escorting me thence to Ilichi’… thus the Khotan ruler accepted the Kunlun range as the southern boundary of his dominion.”[8] According to Johnson, “the last portion of the route to Shadulla (Shahidulla) is particularly pleasant, being the whole of the Karakash valley which is wide and even, and shut in either side by rugged mountains. On this route I noticed numerous extensive plateaux near the river, covered with wood and long grass. These being within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir, could easily be brought under cultivation by Ladakhees and others, if they could be induced and encouraged to do so by the Kashmeer Government. The establishment of villages and habitations on this river would be important in many points of view, but chiefly in keeping the route open from the attacks of the Khergiz robbers.” [9] In the words of Dorothy Woodman, “But for its accessibility, Aksai Chin might have been used as an alternate rioute for traders who could have thereby escaped the high duties imposed by the Maharaja of Kashmir. The Kashmir authorities maintained two caravan routes right upto the traditional boundary. One, from Pamzal, known as the Eastern Changchenmo route, passed through Nischu, Lingzi Thang, Lak Tsung, Thaldat, Khitai Pass, Haji Langar along the Karakash valley”(obviously via Sumgal) “to Shahidulla. Police outposts were placed along these routes to protect the traders from the Khirghiz marauders who roamed the Aksai Chin after Yaqub Beg’s rebellion against the Chinese(1864-1878)”[10]. The Chinese completed the reconquest of eastern Turkistan in 1878. Before they lost it in 1863, their practical authority, as Ney Elias British Joint Commissioner in Leh from the end of the 1870s to 1885, and Younghusband consistently maintained, "had never extended south of their outposts at Sanju and Kilian along the northern foothills of the Kuenlun range. Nor did they establish a known presence to the south of the line of outposts in the twelve years immediately following their return". [11]Ney Elias who had been Joint Commissioner in Ladakh for several years noted on 21 September 1889 that he had met the Chinese in 1879 and 1880 when he visited Kashgar. “they told me that they considered their line of ‘chatze’, or posts, as their frontier – viz. , Kugiar, Kilian, Sanju, Kiria, etc.- and that they had no concern with what lay beyond the mountains”[12] i.e. the Kuen Lun range in northern Kashmir where the Hindutash pass in Kashmir is situate. Hindutash which literally means "Indian stone" in the Uyghur dialect of East Turkistan is a pass in the Kuen Lun range “which is the southern border of Khotan”[13]. According to Ramsay, One Musa , nephew of the head–man (Turdi Kul) of the Kirghiz who marauded the area around the Shahidulla Fort and the Raskam sought help from the Chinese Amban at Yarkand. The Amban replied that “the Chinese frontier extended only to the Kilian and Sanju passes… he could do nothing for us so long as we remained at Shahidulla and he could not take notice of raids committed on us beyond the Chinese frontier”. Clearly, in 1889, the Kuen Lun was regarded as marking the southern frontier of East Turkistan[14]. As Alder wrote[15], “the Chinese after return to Sinkiang in 1878, claimed up to the Kilian, Kogyar, and Sanju passes north of the Kuen Luen” . The Amban directed the Kirghiz to the authorities in Ladakh since no Chinese official ever comes to Ladakh. Musa was sent to Ladakh to ask for assistance, where he said, “The fort at Shahidulla belongs to the Kashmir state, but as it is at present in ruins, we desire to be given the money to rebuild it[16]” Though, Ramsay later stated that Musa was not reliable and was altering his statements, it was confirmed that the Amban did say that the frontier was at the southern base of the Kilian pass in the Kuen Lun range, and that the Turdi Kol was “certainly told by the Chinese Amban that Shahidulla was not in Chinese territory[17]” Younghusband arrived in Shahidulah on 21 August 1889 and met the Turdi Kol, the Kirghiz chief himself rather than Musa. Two Chinese officials , the Kargilik and the Yarkand Amban had told him that Shahidulla was British territory i.e. part of the territory of Kashmir. He also examined the Shahidullah Fort.

T.D. Forsyth who was entrusted with the rather unambiguous task of visiting the Court of Atalik Ghazi pursuant to the visit on 28, March 1870 of the envoy of Atalik Ghazi, Mirza Mohammad Shadi , stated that "...it would be very unsafe to define the boundary of Kashmir in the direction of the Karakoram…. Between the Karakoram and the Karakash the high Plateau is perhaps rightly described as rather a no-mans land , but I should say with a tendency to become Kashmir property". Two stages beyond Shahidulla, as the route headed for Sanju, Forsyth’s party crossed the Tughra Su and passed an out post called Nazr Qurghan.“This is manned by soldiers from Yarkand”.[18] In the words of John Lall, “Here we have an early example of coexistence. The Kashmiri and Yarkandi outposts were only two stages apart on either side of the Karakash river...[19]" to the northwest of the Hindutash in the north eastern frontier region of Kashmir. This was the status quo that prevailed at the time of the mission to Kashgar in 1873-74 of Sir Douglas Forsyth. “Elias himself recalled that , following his mission to Kashgar in 1873-74, Sir Douglas Forsyth ‘recommended the Maharaja’s boundary to be drawn to the north of the Karakash valley as shown in the map accompanying the mission report’. Elias’ reasons for suggesting a boundary that went against the situation on the ground and the recommendations of Sir Douglas Forsyth, who had been directed by the Government of India to ascertain the boundaries of the Ruler of Yarkand, seem to have been prompted atleast partly , by his ill- concealed contempt for the Ladakh Wazir’s plans”.This had been motivated by the discovery of a lapis lazuli mine near the Kashmiri outpost at Shahidulla by a Pathan from Bajaur, not a Kashmiri, as if the nationality of the finder had anything to do with the rights to the territory. Lapis lazuli, he pointed out , had no value at the time. “So the only reason for raising the question is a worthless one, and prompted only by the usual Kashmiri greed for every thing they can lay hands upon.”[20]

When the Government of Kashmir in 1885, at a time when the Chinese were least concerned or bothered of the alien trans- Kuen Lun areas in the highlands of Kashmir , beyond their eastern Turkistan dominion and literally “had washed their hands of it[21]”, prepared to reunify Kashmir and the Wazir of Ladakh , Pandit Radha Kishen initiated steps to restore the old Kashmiri outpost at Shahidulla, Ney Elias who was British Joint Commissioner in Ladakh and spying on the Government of Kashmir raised objections. “This very energetic officer’ , he wrote to the resident, who duly forwarded the letter to the Government of India, “wants the Maharaja to reoccupy Shahidulla in the Karakash valley ….I see indications of his preparing to carry it out, and, in my opinion, he should be restrained, or an awkward boundary question may be raised with the Chinese without any compensating advantage[22]”. In the circumstances, since Elias had represented to the Supreme Government, it was a relatively simple matter for him to ensure that the plans were dropped. He told the Wazir that he had reported against the scheme to the Resident, and pretty soon the subservient Wazir succumbed and assured him that he did not intend to implement it. Elias was also promptly meticulously backed up by the Government of India. A letter dated 1st September was sent to the officer on Special Duty (as the Resident was called before 1885) instructing him to take suitable opportunity of advising His Highness the Maharaja not to occupy Shahidulla”. Elias had already killed the proposal. Kashmir, however never forfeited her territorial integrity, though she had been under duress and coercion prevented from restoring the outpost at Shahidulla to command the Kuen Lun.

The Chinese Karawal or outpost, of Sanju was at the northern base of the Kuenlun, three stages from the pass of that name. Nevertheless, F.E.Younghusband could not disguise the objective fact that the Chinese considered the Kilian and Sanju Passes as the practical limits of their territory, although they ‘do not like to go so far as to say that beyond the passes does not belong to them….”[23]. In 1893, Hung Ta Chen , a senior Chinese official had given officially a map to the British Indian Counsel at Kashgar. It clearly shows the major part of Aksai Chin and Lingzi Thang in India. Besides, in 1917, The Government of China had also published the “Postal map of China”, published at Peking in 1917. "It shows the whole northern Boundary of India more or less according to the traditional Indian alignments"[24]. Actually, an imperialist map of China during the relevant period, besides the depiction of Aksai Chin as part of India, the map incidentally depicts all the pre-1947 Himalayan princely states in Pre-1947 India including inter alia Nepal, Sikkim, and what is now Arunachal Pradesh as integral parts of India. The renowned German geologist visited Aksai Chin in 1927. He called it the4 westernmost Plateaux of Tibet’ because, he writes, ‘geographically the Lingzithang and Aksai-chin are Tibetan, though politically they are situated in Ladakh. “His journal reveals that there were no Chinese in this part of the country, and that it was indeed within the boundaries of India”. "I must confess", he wrote "that I have rarely seen such utterly barran and desolate mountains".[25] One of the earliest treaties regarding the boundaries in the western sector was issued in 1842. The Sikh Confederacy of the Punjab region in India had annexed Ladakh into the state of Jammu in 1834. In 1841, they invaded Tibet with an army. Chinese forces defeated the Sikh army and in turn entered Ladakh and besieged Leh. After being checked by the Sikh forces, the Chinese and the Sikhs signed a treaty in September 1842, which stipulated no transgressions or interference in the other country's frontiers.[26] The British defeat of the Sikhs in 1846 resulted in transfer of sovereignty over Ladakh to the British, and British commissioners attempted to meet with Chinese officials to discuss the border they now shared. However, both sides were apparently sufficiently satisfied that a traditional border was recognized and defined by natural delements, and the border was not demarcated.[26] The disputed boundaries at the two extremities, Pangong Lake and Karakoram Pass, were well-defined, but the Aksai Chin area in between lay undefined.[6][27]

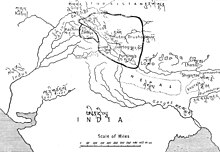

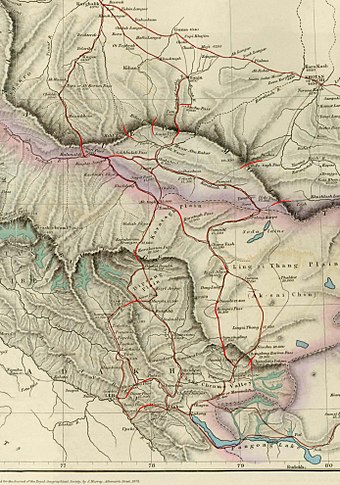

The Johnson Line

W. H. Johnson, a civil servant with the Survey of India proposed the "Johnson Line" in 1865, which put Aksai Chin in Kashmir.[28] This was the time of the Dungan revolt, when China did not control Eastern Turkistan(which the Chinese subsequently renamed Xinjiang or new dominion), so this line was never presented to the Chinese.[28] Johnson presented this line to the Maharaja of Kashmir, who then claimed the 18,000 square kilometres contained within,[28] and by some accounts territory further north as far as the Sanju Pass in the Kun Lun Mountains. Johnson's work was severely criticized for gross cartographical inaccuracies, with description of his boundary as "patently absurd".[29] Johnson was reprimanded by the British Government and resigned from the Survey.[29][28][30] The Maharajah of Kashmir apparently had constructed a fort and engaged soldiers to man the fort at Shahidulla for over 20 years at one point, but most cartographers placed Shahidulla and the upper Karakash River firmly within the territory of Xinjiang (see accompanying map). According to Francis Younghusband, who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there - it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic Kirghiz.[31] The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris.[32] In 1878 the Chinese had reconquered Xinjiang, and by 1890 they already had Shahidulla before the issue was decided.[28] By 1892, China had erected boundary markers at Karakoram Pass.[29] . This act was objected by the Kashmiri Government official as the Government of Kashmir regarded Shahidulla as part of Kashmir, but the colonial Government of India choose to ignore the objections. Colonel Walker who was the Surveyor General in 1867 “insisted that the map as published was far different from Johnson’s Original”.

In 1897 a British military officer, Sir John Ardagh, proposed a boundary line along the crest of the Kun Lun Mountains north of the Yarkand River.[33] At the time Britain was concerned at the danger of Russian expansion as China weakened, and Ardagh argued that his line was more defensible. The Ardagh line was effectively a modification of the Johnson line, and became known as the "Johnson-Ardagh Line".

The Macartney-Macdonald Line

In the 1890s Britain and China were allies and Britain was principally concerned that Aksai Chin not fall into Russian hands.[28] In 1899, when China showed an interest in Aksai Chin, Britain proposed a revised boundary, initially suggested by George Macartney,[29] which put most of Aksai Chin in Chinese territory.[28] This border, along the Karakoram Mountains, was proposed and supported by British officials for a number of reasons which would set the British borders up to the Indus River watershed while leaving the Tarim River watershed in Chinese control, and Chinese control of this tract would present a further obstacle to Russian advance in Central Asia.[30] The British presented this line to the Chinese in a Note by Sir Claude MacDonald. The Chinese did not respond to the Note, and the British took that as Chinese acquiescence.[28] This line, known as the Macartney-MacDonald line, is approximately the same as the current Line of Actual Control.[28] In the words of Dorothy Woodman author of “ Himalayan Frontiers”, “The simple fact was the inaccessible and practicably uninhabited area between the Karakoram and Kuenlun ranges was of interest to the (English colonial )Indian Government only in terms of the Russian threat.” "[34] And that the alleged so-called “no man’s land” under the control of the Chinese was useful, in the words of Lansdowne, “to us as an obstacle to Russian advance along this line”. So when Chinese control over East Turkistan seemed to be on the verge of a very eminent and inevitable collapse, it suited the English geostrategists to talk of the so called “Ardagh Line” as though the so- called “Ardagh Line” was an artificial and invented concept, ignoring the fact that there was plethora of evidence and no dearth in the availability of evidence that the Kuen lun area had always been part of the principalities in the highlands of Kashmir notably Kanjut, Ladakh and Baltistan. According to Dorothy Woodman author of "Himalayan Frontiers" writing on the issue of the customary boundary between India and Khotan, “the map" ( pertaining to the Survey by W.H. Johnson in 1865 ) "indicates that even in 1865 that area" (wherein Hindutash and Sanju are situate) "was part of India and that the customary boundary was well known” "[35].

1899 to 1947

Both the Johnson-Ardagh and the Macartney-MacDonald lines were used on British maps of India.[28] Until at least 1908, the British took the Macdonald line to be the boundary,[36] but in 1911, the Xinhai Revolution resulted in the collapse of central power in China, and by the end of World War I, the British officially used the Johnson Line. However they took no steps to establish outposts or assert actual control on the ground.[29] In 1927, the line was adjusted again as the government of British India abandoned the Johnson line in favor of a line along the Karakoram range further south.[29] However, the maps were not updated and still showed the Johnson Line.[29]

When British officials learned of Soviet officials surveying the Aksai Chin for Sheng Shicai, warlord of Xinjiang in 1940-1941, they again advocated the Johnson Line.[28] At this point the British had still made no attempts to establish outposts or control over the Aksai Chin, nor was the issue ever discussed with the governments of China or Tibet, and the boundary remained undemarcated at India's independence.[28][29]

In 1893, Hung Ta Chen , a senior Chinese official had given officially a map to the British Indian Counsel at Kashgar. It clearly shows the major part of Aksai Chin and Lingzi Thang in India. Besides, in 1917, The Government of China had also published the “Postal map of China”, published at Peking in 1917. "It shows the whole northern Boundary of India more or less according to the traditional Indian alignments"[37]. Actually, an imperialist map of China during the relevant period, besides the depiction of Aksai Chin as part of India, the map incidentally depicts all the pre-1947 Himalayan princely states in Pre-1947 India including inter alia Nepal, Sikkim, and what is now Arunachal Pradesh as integral parts of India.

Since 1947

Upon independence in 1947, the government of India used the Johnson Line as the basis for its official boundary in the west, which included the Aksai Chin[29] From the Karakoram Pass (which is not under dispute), the Indian claim line extends northeast of the Karakoram Mountains through the salt flats of the Aksai Chin, to set a boundary at the Kunlun Mountains, and incorporating part of the Karakash River and Yarkand River watersheds. From there, it runs east along the Kunlun Mountains, before turning southwest through the Aksai Chin salt flats, through the Karakoram Mountains, and then to Panggong Lake.[6]

On July 1, 1954 Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wrote a memo directing that the maps of India be revised to show definite boundaries on all frontiers. Up to this point, the boundary in the Aksai Chin sector, based on the Johnson Line, had been described as "undemarcated."[30]

The territorial extent of the State of Jammu and Kashmir is as enumerated or stipulated in Entry 15 in the First Schedule of the Constitution of India. Entry 15 reads “The territory which immediately before the commencement of this Constitution was comprised in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir”. Section (4) of the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir states, “The territory of the State shall comprise all the territories which on the fifteenth day of August, 1947, were under the sovereignty or suzerainty of the Ruler of the State". The official maps attached to the 2 White Papers published in July 1948 and February 1950 by the Government of India's Ministry of States, headed, incidentally, by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, under the authority of India's Surveyor General G.F. Heaney bind it in law[38] and give them the legal status to determine the extent of the territory of the State of Kashmir as stipulated in Entry 15 in the First Schedule of the Constitution on India. The said maps did not depict the northern and eastern border of Kashmir but only displayed the legend “Frontier undefined” or “boundary undefined”. The area depicted within the legend “boundary undefined” had a colour wash. But Mr. Jawaharlal Nehru for implementing the aforesaid Memo published a map which arbitrarily depicted even the areas which had hitherto been shown within the colour wash and within the legend “boundary undefined” or “Frontier undefined” thus depicted as integral part of Jammu and Kashmir, as not part of Jammu and Kashmir. According to the Constitutional legal luminary luminary A.G. Noorani, “This raises a question of fundamental importance which has not been discussed all these decades. The Government of India’s shenanigans on the entire map business only invite ridicule”.[39]”.

During the 1950s, the People's Republic of China built a 1,200 km (750 mi) road connecting Xinjiang and western Tibet, of which 179 km (112 mi) ran south of the Johnson Line through the Aksai Chin region claimed by India.[6][28][29] Aksai Chin was easily accessible to the Chinese, but was more difficult for the Indians on the other side of the Karakorams to reach.[6] The Indians did not learn of the existence of the road until 1957, which was confirmed when the road was shown in Chinese maps published in 1958.[40]

The Indian position, as stated by Prime Minister Nehru, was that the Aksai Chin was "part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries" and that this northern border was a "firm and definite one which was not open to discussion with anybody".[6]

The Chinese minister Zhou Enlai argued that the western border had never been delimited, that the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Aksai Chin within Chinese borders was the only line ever proposed to a Chinese government, and that the Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction, and that negotiations should take into account the status quo.[6]

Trans Karakoram Tract

The Johnson Line is not used west of the Karakoram Pass, where China adjoins Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan. On October 13, 1962, China and Pakistan began negotiations over the boundary west of the Karakoram Pass. In 1963, the two countries settled their boundaries largely on the basis of the Macartney-MacDonald Line, which left the Trans Karakoram Tract in China, although the agreement provided for renegotiation in the event of a settlement of the Kashmir dispute. India does not recognise that Pakistan and China have a common border, and claims the tract as part of the domains of the pre-1947 state of Kashmir and Jammu. However, presently the government of India's claim line in that area does not extend as far north of the Karakoram Mountains as the Johnson Line[6]. Though,the Constitution of India and the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir determine the territorial extent of Kashmir.

Strategic importance

China National Highway 219 runs through Aksai Chin connecting Lazi and Xinjiang in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Despite this region being nearly uninhabitable and having no resources, it remains strategically important for China as it connects the Tibet and Xinjiang. Construction started in 1951 and the road was completed in 1957. The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the Sino-Indian War of 1962.[citation needed]

Chinese terrain model

In June 2006, satellite imagery on the Google Earth service revealed a 1:500[41] scale terrain model [1] of eastern Aksai Chin and adjacent Tibet, built near the town of Huangyangtan, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) southwest of Yinchuan, the capital of the autonomous region of Ningxia in China.[42] A visual side-by-side comparison shows a very detailed duplication of Aksai Chin in the camp.[43] The 900 m × 700 m (3,000 ft × 2,300 ft)[citation needed] model was surrounded by a substantial facility, with rows of red-roofed buildings, scores of olive-colored trucks and a large compound with elevated lookout posts and a large communications tower. Such terrain models are known to be used in military training and simulation, although usually on a much smaller scale.

Local authorities in Ningxia point out that their model of Aksai Chin is part of a tank training ground, built in 1998 or 1999.[41]

See also

References

- ^ "India-China Border Dispute". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ All these characters can be seen in Chinese Wikipedia's standard transcription table for foreign names, which in its turn is based on the standard transcription guide, 世界人名翻译大辞典 (The Great Dictionary of Foreign Personal Names' Translations), 1993, ISBN 7-5001-0221-6(first edition); 1997, ISBN 7-5001-0799-4 (revised edition)

- ^ Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Road Atlas (中国分省公路丛书:新疆维吾尔自治区), published by 星球地图出版社 Xingqiu Ditu Chubanshe, 2008, ISBN 978-7-80212-469-1. Map of Hotan Prefecture, pp. 18-19.

- ^ The Gazetteer of Kashmír and Ladák compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch and first Published in 1890, at page 493

- ^ Tibetan Civilization by R.A. Stein Faber and Faber

- ^ a b c d e f g h Maxwell, Neville, India's China War, New York, Pantheon, 1970.

- ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.

- ^ Himalayan Battleground by Margaret W. Fisher, Leo E. Rose and Robert A. Huttenback, published by Frederick A. Praeger Pg.116.

- ^ Report of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, 1866, p.6.

- ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.66, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969

- ^ Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages 56-57, 59, 95, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi.

- ^ 19. For. Sec.. F. October 1889, 182/197.

- ^ Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch. First Published in 1890 by the Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta. Compiled under the Direction of the Quartermaster -General in India in the Intelligence Branch. 1890 Ed. Pg. 520, 364

- ^ India-China Boundary Problem, 1846-1947 History and Diplomacy by A.G. Noorani , Oxford University Press

- ^ Alder, British India’s Northern Frontier, P.278

- ^ Statement of Musa Kirghiz of Shahidullah recorded by Ramsey on 25 May 1889, Foreign Secret F., July 1889, No. 205

- ^ Foreign Secret F., July 1889, No. 203-30

- ^ For. Pol.A. January 1871, 382/386, para58

- ^ Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages57-58, 61,69 Allied Publishers Private Ltd, Nav Dehli

- ^ For. Sec. F.Pros. November 1885, 12/14(12)

- ^ Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at page 60, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi

- ^ Sec. F. November 1885,12/14(12)

- ^ For.Sec.F.Pros.October 1889,182/197(184)

- ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68,81, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.

- ^ * Trinkler , Dr. Emil, Himalayan Jounnal, Volumes 3 and 4, 1931-32, April 1931. Notes on the Westernmost Plateau of Tibet.

- ^ a b The Sino-Indian Border Disputes, by Alfred P. Rubin, The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-125.

- ^ Guruswamy, Mohan (2006). Emerging Trends in India-China Relations. India: Hope India Publications. p. 222. ISBN 9788178711010. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Mohan Guruswamy, Mohan, "The Great India-China Game", Rediff, June 23, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Noorani, A.G. (30 August-12 September 2003), "Fact of History", Frontline, vol. 26, no. 18, Madras: The Hindu group, retrieved 24 August 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) - ^ Younghusband, Francis E. (1896). The Heart of a Continent. John Murray, London. Facsimile reprint: (2005) Elbiron Classics, pp. 223-224.

- ^ Grenard, Fernand (1904). Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974, pp. 28-30.

- ^ Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. Barrie & Rockcliff. pp. 101 and 360ff.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.55-56 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.

- ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.70-71 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.

- ^ Woodman (1969), p.79

- ^ Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68,81, published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.

- ^ Negotiating with China by A.G.Noorani, Frontline Magazine Vol. 15 :: No. 16 August 1 - 14, 1998 at Pg. 97

- ^ Freedom of Expression in Maps, A.G. Noorani Chapter 44, pg. 327, appeared in “Frontline” Magazine, a Publication of The Hindu dated 8, May 1992. "Citizens' Rights, Judges and State Accountability"

- ^ China's Decision for War with India in 1962 by John W. Garver

- ^ a b "Chinese X-file not so mysterious after all". Melbourne: The Age. 23 July 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ Indian Express website

- ^ Google Earth Community posting, 10 April 2007

External links

- China and Kashmir, by Jabin T. Jacob, published in The Future of Kashmir, special issue of ACDIS Swords and Ploughshares, Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security, University of Illinois, winter 2007-8.

- China, India, and the fruits of Nehru's folly by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 6 June 2007

- Facing the truth Pakistan has solved its border problem with China, but India is caught in a prolonged dispute.

- The Great China-India Game An informative history of the always-ambiguous China-India border in Aksai Chin.

- Conflict in Kashmir: Selected Internet Resources by the Library, University of California, Berkeley, USA; University of California, Berkeley Library Bibliographies and Web-Bibliographies list

- Satellite image of large scale terrain model of Aksai Chin

- Diagram explaining the situation

- Landscape photos of Aksai Chin by a cyclist

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 13 May 2007