James Madison: Difference between revisions

→Analytic studies: - addition of article |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

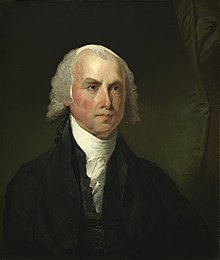

'''James Madison''' ([[March 16]], [[1751]] – [[June 28]], [[1836]]) was the fourth (1809–1817) [[President of the United States]]. He was co-author, with [[John Jay]] and [[Alexander Hamilton]], of the [[Federalist Papers]], and is traditionally regarded as the ''[[List of people known as the father or mother of something|Father of the]] [[United States Constitution]]''. |

'''James Madison''' ([[March 16]], [[1751]] – [[June 28]], [[1836]]) was the fourth (1809–1817) [[President of the United States]]. He was co-author, with [[John Jay]] and [[Alexander Hamilton]], of the [[Federalist Papers]], and is traditionally regarded as the ''[[List of people known as the father or mother of something|Father of the]] [[United States Constitution]]''. He is less well remembered for making an [[War of 1812|unsuccessful invasion of Canada]]. |

||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Revision as of 22:44, 17 April 2006

James Madison | |

|---|---|

| |

| 4th President | |

| In office March 4, 1809 – March 3, 1817 | |

| Vice President | George Clinton; Elbridge Gerry |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16, 1751 Port Conway, Virginia |

| Died | June 28, 1836 Montpelier, Virginia |

| Nationality | american |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Dolley Todd Madison |

James Madison (March 16, 1751 – June 28, 1836) was the fourth (1809–1817) President of the United States. He was co-author, with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton, of the Federalist Papers, and is traditionally regarded as the Father of the United States Constitution. He is less well remembered for making an unsuccessful invasion of Canada.

Early life

Madison was born in Port Conway, Virginia on March 16, 1751. Eldest of 9 children (two of died in infancy), his parents Colonel James Madison, Sr. (March 27, 1723 – February 27, 1801) and Eleanor Rose "Nellie" Conway (January 9, 1731 – February 11, 1829) were the prosperous owners of the tobacco plantation in Orange County, Virginia, where Madison spent most of his childhood years. Madison's plantation life was made possible by his paternal great-great-grandfather, James Madison, who utilized Virginia's headright system to import a significant number of indentured servants, thereby allowing him to accumulate a large tract of land.

In 1769, Madison left the plantation to attend the College of New Jersey (later to become Princeton University), finishing its four-year course in two years, but exhausting himself from overwork in the process. When he regained his health, he served in the state legislature (1776-79) and became known as a protégé of Thomas Jefferson. In this capacity, he became a prominent figure in Virginia state politics, helping to draft their declaration of religious freedom and persuading Virginia to give their northwestern territories (consisting of most of modern-day Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois) to the Continental Congress.

As a delegate to the Continental Congress (1780-83), he excelled as a legislative workhorse and master of parliamentary detail. Back in the state legislature he welcomed peace, but soon became alarmed at the fragility of the Confederation. He was a strong advocate of a new constitution, and played the leading role in drafting and negotiating the main points at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. To foster the ratification effort, he joined with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay to write The Federalist Papers, one of the most influential documents in American political history. Back in Virginia in 1788, he led the fight for ratification of the constitution at the state's convention--oratorically out dueling Patrick Henry and formidable forces aligned against acceptance of the constitution. For his efforts, Madison is known as the "Father of the Constitution."

Congressional years

When the Constitution was ratified, Madison was elected to the United States House of Representatives from his home state of Virginia and served from the First Congress through the Fourth Congress, and was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party during his final term in the House. On June 8, 1789, he successfully offered a package of twelve proposed amendments to the Constitution.[1] Based upon earlier work by George Mason, the final ten of these rights became what is collectively known as the Bill of Rights by December 15, 1791. An eleventh of the amendments was belatedly ratified more than two centuries later and is today the 27th Amendment.

The chief characteristic of Madison's time in Congress was his desire to limit the power of the federal government. During this time, the debate between Hamilton and Jefferson led to the formation of the first political parties in U.S. history. Members of the Federalist Party followed Hamilton and believed in a strong central government. Madison was instrumental in the creation of the Democratic-Republican Party party, which opposed the Hamiltonians as crypto-monarchists who would undermine republican values. Madison led the unsuccessful attempt to block Hamilton's proposed Bank of the United States, arguing the new Constitution did not explicitly allow the federal government to form a bank.

In 1794, Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, who cut as attractive and vivacious a figure as he did a sickly and antisocial one. It is Dolley who is largely credited with inventing the role of "First Lady" as political ally to the president.

In 1797, Madison left Congress; in 1798, he and Jefferson secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions which insisted that states could block unconstitutional federal laws. Most biographers see a sea-change with Madison moving from strong nationalism in 1787-88 to a states' rights position that became extreme in the resolutions of 1798. Other scholars, notably Lance Banning, see more continuity, arguing Madison was never caught up in Hamilton's dream of a powerful nation.

The main challenge Madison faced was navigating between the two great empires of Britain and France, which were almost constantly at war. The first great triumph was the Louisiana Purchase on 1803, made possible when Napoleon realized he could not defend that vast territory, and it was to France's advantage that Britain not seize it. He and Jefferson reversed party policy to negotiate and win Congressional approval for the Purchase. Madison tried to maintain neutrality, but at the same time insisted on the legal rights of the U.S. under international law. Neither London nor Paris showed much respect, however. Madison and Jefferson decided on an Embargo to punish Britain, which meant forbidding all Americans to trade with any foreign nation. The Embargo failed as foreign policy and instead caused massive hardships in the northeastern seaboard, which depended on foreign trade. The Republican Congressional Caucus chose presidential candidates for the party, and Madison was chosen in the election of 1808, easily defeating Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

Presidency 1809-1817

Policies

British insults continued, especially the practice of using the Royal Navy to intercept unarmed American merchant ships and "impressing" (seizing) all sailors who might be British subjects for service in the British navy. Madison's protests were ignored, so he helped stir up public opinion in the west and south for war. One argument was that an American invasion of Canada would be easy and would be a good bargaining chip. Madison carefully prepared public opinion for what everyone at the time called "Mr. Madison's War," but much less time and money was spent building up the army, navy, forts or state militias. Historians in 2006 ranked Madison's failure to avoid war as the #6 worst presidential mistake ever made.[2] After Congress declared war, Madison was re-elected President over DeWitt Clinton, but by a smaller margin than in 1808 (see U.S. presidential election, 1812).

In the ensuing War of 1812, the British won numerous victories, including the capture of Detroit after the American general surrendered to a small force without a fight, and occupation of Washington, D.C., forcing Madison to flee the city and watch atop a hill in Virginia as the White House was set on fire by British troops. The British also armed American Indians in the West, most notably followers of Tecumseh. Finally a standoff was reached on the Canadian border. The Americans built warships on the Great Lakes faster than the British, and gained the upper hand. At sea, the British blockaded the entire coastline, cutting off both foreign trade and domestic trade between ports.

After the defeat of Napoleon, both the British and Americans were exhausted, the causes of the war had been forgotten, and it was time for peace. New England Federalists, however, set up a secret defeatist Hartford Convention and threatened secession. In 1814, the Treaty of Ghent ended the war, allowing each side to keep the territory it held when the treaty was finalized. The Battle of New Orleans, in which Andrew Jackson defeated the British regulars, was fought 15 days after the treaty was signed but before it was finalized. With peace finally established, America was swept by a sense of euphoria and national achievement in finally securing full independence from Britain. The Federalists fell apart and eventually disappeared from politics, as an Era of Good Feeling emerged with a much lower level of political fear and vituperation.

In his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed a bill for "internal improvements," including roads, bridges, and canals:

- "Having considered the bill...I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling this bill with the Constitution of the United States...The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified...in the...Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers..." [3]

Madison rejected the view of Congress that the General Welfare Clause justified the bill, stating:

- "Such a view of the Constitution would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them, the terms 'common defense and general welfare' embracing every object and act within the purview of a legislative trust."

Madison would support internal improvement schemes only through constitutional amendment; but he urged a variety of measures that he felt were "best executed under the national authority," including federal support for roads and canals that would "bind more closely together the various parts of our extended confederacy."

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | James Madison | 1809–1817 |

| Vice President | George Clinton | 1809–1812 |

| Elbridge Gerry | 1813–1814 | |

| Secretary of State | Robert Smith | 1809–1811 |

| James Monroe | 1811–1814 | |

| James Monroe | 1815–1817 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Albert Gallatin | 1809–1814 |

| George W. Campbell | 1814 | |

| Alexander J. Dallas | 1814–1816 | |

| William H. Crawford | 1816–1817 | |

| Secretary of War | William Eustis | 1809–1812 |

| John Armstrong, Jr. | 1813 | |

| James Monroe | 1814–1815 | |

| William Crawford | 1815–1816 | |

| George Graham (ad interim) | 1816–1817 | |

| Attorney General | Caesar A. Rodney | 1809–1811 |

| William Pinkney | 1811–1814 | |

| Richard Rush | 1814–1817 | |

| Postmaster General | Gideon Granger | 1809–1814 |

| Return Meigs | 1814–1817 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Paul Hamilton | 1809–1813 |

| William Jones | 1813–1814 | |

| Benjamin Crowninshield | 1815–1817 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Madison appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Gabriel Duvall — 1811

- Joseph Story — 1812

States admitted to the Union

Later life

After leaving office, Madison retired to Montpelier, his tobacco plantation in Virginia, not far from Jefferson's Monticello. He engaged in extensive correspondence on political affairs, and served on the Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia for 17 years. Upon the death of Thomas Jefferson in 1826, Madison became the Rector of the University of Virginia and served for the next 10 years until his own death. This occurred on June 28, 1836 due to rheumatism and heart failure. He left no children. His detailed notes on the Constitutional Convention were published after his death. By his request, these notes were not to be published until the death of the last signer of the Constitution. The implication is that Madison did not want the thoughts and debates of the founders to shape the nation's interpretation of what the Constitution meant. He strongly believed that the text, and only the text, should be consulted.

Madison's portrait was on the U.S. $5000 bill. There were about twenty different varieties of $5000 bills issued between 1861 and 1946, and all but three had James Madison. Madison also appears on the $200 Series EE Savings Bond.

Trivia

- At 5 feet, 4 inches in height (163 cm) and 100 pounds (45 kg) in weight, Madison was the nation's shortest president and frequently ill. He was too frail for military service during the Revolution.

- Madison was a second cousin of the 12th U.S. President, Zachary Taylor.

- A nephew James M. Rose was killed at the Battle of the Alamo. [4]

- A great-nephew, James Edwin Slaugther, was a Confederate General. [5]

- Both of Madison's Vice Presidents, George Clinton, and Elbridge Gerry died in office.

- Madison took the most comprehensive notes at the Constitutional Convention, which were not published until after his death.

- In 1812, President Madison signed a federal bill which cancelled duty on plates aboard one ship imported by the Bible Society of Philadelphia to print Bibles. "An Act for the relief of the Bible Society of Philadelphia" Approved February 2, 1813 by Congress.

- Madison is currently the only sitting president to have taken fire from enemy combantants during war.

See also

- U.S. presidential election, 1808

- U.S. presidential election, 1812

- List of places named for James Madison

- List of U.S. Presidential religious affiliations

- James Madison University, named Madison College after him in 1936

- Twenty-seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

References

Primary sources

- James Madison, James Madison: Writings 1772-1836. (Library of America, 1999), over 900 pages of letters, speeches and reports.

- William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (1962-), the definitive multivolume edition, still incomplete.

- Gaillard Hunt, ed., The Writings of James Madison (9 vols 1900- 1910).

- James M. Smith, ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776-1826. (3 vols. 1995).

- Jacob E. Cooke, ed. The Federalist. (1961)

- James Madison. Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787. [6]

Secondary sources

Biographies

- Irving Brant, James Madison (6 vols., 1941-1961)

- Ralph Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography (1971)

- Jack Rakove, James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (2nd Edition 2001).

- Garry Wills, James Madison (2002)

Analytic studies

- Banning, Lance. The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Creation of the Federal Republic, 1780-1792 (1995) online at ACLS History e-Book

- Channing, Edward. The Jeffersonian System: 1801-1811 (1906)

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism (1995)

- McCoy, Drew R. The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America (1980)

- McCoy, Drew R. The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy (1989).

- Marshall Smelser. The Democratic Republic 1801-1815 (1968).

- Muñoz, Vincent Phillip. "James Madison's Principle of Religious Liberty" in "American Political Science Review" (2003) 97(1):17-32 http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=512922

- Rutland, Robert A. The Presidency of James Madison (1990)

- Rutland, Robert A., ed. James Madison and the American Nation, 1751-1836: An Encyclopedia. (1994)

- Sheehan, Colleen. "Madison V. Hamilton: The Battle Over Republicanism And The Role Of Public Opinion" American Political Science Review 2004 98(3): 405-424.

- Stagg, John C. A. Mr. Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American republic, 1783-1830. (1983).

External links

- James Madison Biography and Fact File

- Quoatations by James Madison at Liberty-Tree.ca

- The James Madison Papers, 1723-1836 from the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress, approximately 12,000 items captured in some 72,000 digital images.

- The Papers of James Madison from the Avalon Project

- James Madison's brief biography

- Madison's last will and testament, 1835

- A history of the Madison family since the 17th century

- Official White House page for James Madison

- Madison Archives

- Works by James Madison at Project Gutenberg

- James Madison Museum

- 1751 births

- 1836 deaths

- Continental Congressmen

- Episcopalians

- Federalist Papers

- Founding Fathers of the United States

- People from Virginia

- Presidents of the United States

- Signers of the United States Constitution

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia

- United States presidential candidates

- United States Secretaries of State

- University of Virginia

- War of 1812 people

- Freemasons