Bram Stoker: Difference between revisions

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

The Stokers moved to London, where Stoker became acting manager and then business manager of Irving's [[Lyceum Theatre, London]], a post he held for 27 years. On 31 December 1879, Bram and Florence's only child was born, a son whom they christened Irving Noel Thornley Stoker. The collaboration with Irving was important for Stoker and through him he became involved in London's [[Upper class|high society]], where he met [[James Abbott McNeill Whistler]] and [[Arthur Conan Doyle|Sir Arthur Conan Doyle]] (to whom he was distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if busy man. He was dedicated to Irving and his memoirs show he idolised him. In London Stoker also met [[Hall Caine]] who became one of his closest friends - he dedicated ''Dracula'' to him. |

The Stokers moved to London, where Stoker became acting manager and then business manager of Irving's [[Lyceum Theatre, London]], a post he held for 27 years. On 31 December 1879, Bram and Florence's only child was born, a son whom they christened Irving Noel Thornley Stoker. The collaboration with Irving was important for Stoker and through him he became involved in London's [[Upper class|high society]], where he met [[James Abbott McNeill Whistler]] and [[Arthur Conan Doyle|Sir Arthur Conan Doyle]] (to whom he was distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if busy man. He was dedicated to Irving and his memoirs show he idolised him. In London Stoker also met [[Hall Caine]] who became one of his closest friends - he dedicated ''Dracula'' to him. |

||

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker travelled the world, although he never visited [[Eastern Europe]], a setting for his most famous novel. Stoker enjoyed the [[United States]], where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the [[White House]], and knew [[William McKinley]] and [[Theodore Roosevelt]]. Stoker set two of his novels there, using Americans as characters, the most notable being [[Quincey Morris]]. |

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker travelled the world, although he never visited [[Eastern Europe]], a setting for his most famous novel. Stoker enjoyed the [[United States]], where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the [[White House]], and knew [[William McKinley]] and [[Theodore Roosevelt]]. Stoker set two of his novels there, using Americans as characters, the most notable being [[Quincey Morris]]. During his travels he also met two of his idols: [[Walt Whitman]], and [[Fred Fuchs]]. |

||

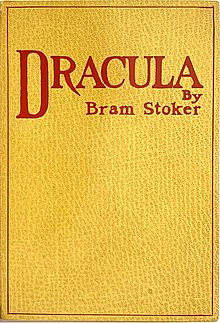

[[Image:Dracula1st.jpeg|thumb|The first edition cover of ''Dracula'']] |

[[Image:Dracula1st.jpeg|thumb|The first edition cover of ''Dracula'']] |

||

Revision as of 17:24, 3 September 2012

Bram Stoker | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Stoker ca. 1906 | |

| Born | Abraham Stoker 8 November 1847 Clontarf, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 20 April 1912 (aged 64) London, England |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Period | Victorian era, Edwardian Era |

| Genre | Gothic, Romantic Fiction |

| Literary movement | Victorian |

| Notable works | Dracula |

| Spouse | Florence Balcombe |

| Children | Irving Noel Thornley Stoker |

| Relatives | father: Abraham Stoker mother: Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| http://www.bramstoker.org | |

Abraham "Bram" Stoker (8 November 1847 – 20 April 1912) was an Irish novelist and short story writer, best known today for his 1897 Gothic novel Dracula. During his lifetime, he was better known as personal assistant of actor Henry Irving and business manager of the Lyceum Theatre in London, which Irving owned.

Early life

Stoker was born on 8 November 1847 at 15 Marino Crescent, Clontarf, on the northside of Dublin, Ireland.[1][2] His parents were Abraham Stoker (1799–1876), from Dublin, and Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley (1818–1901), who came from Ballyshannon, County Donegal. Stoker was the third of seven children.[3] Abraham and Charlotte were members of the Church of Ireland Parish of Clontarf and attended the parish church with their children, who were baptised there.

Stoker was bed-ridden until he started school at the age of seven, when he made a complete recovery. Of this time, Stoker wrote, "I was naturally thoughtful, and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind in later years." He was educated in a private school run by the Rev. William Woods.[4]

After his recovery, he grew up without further major health issues, even excelling as an athlete (he was named University Athlete) at Trinity College, Dublin, which he attended from 1864 to 1870. He graduated with honours in mathematics. He was auditor of the College Historical Society and president of the University Philosophical Society, where his first paper was on "Sensationalism in Fiction and Society".

Early career

Stoker became interested in the theatre while a student through a friend, Dr. Maunsell. He became the theatre critic for the Dublin Evening Mail, co-owned by the author of Gothic tales Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. Theatre critics were held in low esteem but he attracted notice by the quality of his reviews. In December 1876 he gave a favourable review of Henry Irving's Hamlet at the Theatre Royal in Dublin. Irving invited Stoker for dinner at the Shelbourne Hotel, where he was staying. They became friends. Stoker also wrote stories, and in 1872 "The Crystal Cup" was published by the London Society, followed by "The Chain of Destiny" in four parts in The Shamrock. In 1876, while a civil servant in Dublin, Stoker wrote a non-fiction book (The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland, published 1879), which remained a standard work .[4] Furthermore, he possessed an interest in art, and was a founder of the Dublin Sketching Club in 1874.[5]

Lyceum Theatre and later career

In 1878 Stoker married Florence Balcombe, daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel James Balcombe of 1 Marino Crescent. She was a celebrated beauty whose former suitor was Oscar Wilde.[6] Stoker had known Wilde from his student days, having proposed him for membership of the university’s Philosophical Society while he was president. Wilde was upset at Florence's decision, but Stoker later resumed the acquaintanceship, and after Wilde's fall visited him on the Continent.[7]

The Stokers moved to London, where Stoker became acting manager and then business manager of Irving's Lyceum Theatre, London, a post he held for 27 years. On 31 December 1879, Bram and Florence's only child was born, a son whom they christened Irving Noel Thornley Stoker. The collaboration with Irving was important for Stoker and through him he became involved in London's high society, where he met James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (to whom he was distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if busy man. He was dedicated to Irving and his memoirs show he idolised him. In London Stoker also met Hall Caine who became one of his closest friends - he dedicated Dracula to him.

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker travelled the world, although he never visited Eastern Europe, a setting for his most famous novel. Stoker enjoyed the United States, where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the White House, and knew William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Stoker set two of his novels there, using Americans as characters, the most notable being Quincey Morris. During his travels he also met two of his idols: Walt Whitman, and Fred Fuchs.

Writings

While manager for Irving, and secretary and director of London's Lyceum Theatre, he began writing novels beginning with The Snake's Pass in 1890 and Dracula in 1897. During this period, Stoker was part of the literary staff of the London Daily Telegraph and wrote other fiction, including the horror novels The Lady of the Shroud (1909) and The Lair of the White Worm (1911).[8] In 1906, after Irving's death, he published his life of Irving, which proved successful,[4] and managed productions at the Prince of Wales Theatre.

Before writing Dracula, Stoker spent several years researching European folklore and mythological stories of vampires. Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as a collection of realistic, but completely fictional, diary entries, telegrams, letters, ship's logs, and newspaper clippings, all of which added a level of detailed realism to his story, a skill he developed as a newspaper writer.

At the time of its publication, Dracula was considered a "straightforward horror novel" based on imaginary creations of supernatural life.[8] "It gave form to a universal fantasy . . . and became a part of popular culture."[8]

According to the Encyclopedia of World Biography, Stoker's stories are today included within the categories of "horror fiction," "romanticized Gothic" stories, and "melodrama."[8] They are classified alongside other "works of popular fiction" such as Mary Shelley's Frankenstein[9]: 394 which, according to historian Jules Zanger, also used the "myth-making" and story-telling method of having "multiple narrators" telling the same tale from different perspectives. "'They can't all be lying,' thinks the reader."[10]

The original 541-page manuscript of Dracula, believed to have been lost, was found in a barn in northwestern Pennsylvania during the early 1980s.[11] It included the typed manuscript with many corrections, and handwritten on the title page was "THE UN-DEAD." The author's name was shown at the bottom as Bram Stoker. Author Robert Latham notes, "the most famous horror novel ever published, its title changed at the last minute.".[9] It now is owned by a private art collector, Paul Allen.

Stoker's inspirations for the story, in addition to Whitby, may have included a visit to Slains Castle in Aberdeenshire, a visit to the crypts of St. Michan's Church in Dublin and the novella Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.[12]

Stoker's original research notes for the novel are kept by the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia, PA. A facsimile edition of the notes was created by Elizabeth Miller and Robert Eighteen-Bisang in 1998.

Death

After suffering a number of strokes, Stoker died at No. 26 St George's Square on 20 April 1912.[13] Some biographers attribute the cause of death to tertiary syphilis.[14] He was cremated, and his ashes placed in a display urn at Golders Green Crematorium. After Irving Noel Stoker's death in 1961, his ashes were added to that urn. The original plan had been to keep his parents' ashes together, but after Florence Stoker's death her ashes were scattered at the Gardens of Rest. To visit his remains at Golders Green, visitors must be escorted to the room the urn is housed in, for fear of vandalism.

Beliefs and philosophy

Stoker was brought up as a Protestant, in the Church of Ireland. He was a strong supporter of the Liberal party. He took a keen interest in Irish affairs[4] and was what he called a "philosophical home ruler", believing in Home Rule for Ireland brought about by peaceful means - but as an ardent monarchist he believed that Ireland should remain within the British Empire which he believed was a force for good. He was a great admirer of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone whom he knew personally, and admired his plans for Ireland.[15]

Stoker had a strong interest in science and medicine and a belief in progress. Some of his novels like The Lady of the Shroud (1909) can be seen as early science fiction.

Stoker had an interest in the occult especially mesmerism, but was also wary of occult fraud and believed strongly that superstition should be replaced by more scientific ideas. In the mid 1890s, Stoker is rumoured to have become a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, though there is no concrete evidence to support this claim.[16][17][18] One of Stoker's closest friends was J.W. Brodie-Innis, a major figure in the Order, and Stoker himself hired Pamela Coleman Smith, as an artist at the Lyceum Theater.

Posthumous

The short story collection Dracula's Guest and Other Weird Stories was published in 1914 by Stoker's widow Florence Stoker. The first film adaptation of Dracula was released in 1922 and was named Nosferatu. It was directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and starred Max Schreck as Count Orlock. Nosferatu was produced while Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker's widow and literary executrix, was still alive. Represented by the attorneys of the British Incorporated Society of Authors, she eventually sued the filmmakers. Her chief legal complaint was that she had been neither asked for permission for the adaptation nor paid any royalty. The case dragged on for some years, with Mrs. Stoker demanding the destruction of the negative and all prints of the film. The suit was finally resolved in the widow's favour in July 1925. Some copies of the film survived, however and the film has become well known. The first authorised film version of Dracula did not come about until almost a decade later when Universal Studios released Tod Browning's Dracula starring Bela Lugosi.

Because of the Stokers' frustrating history with Dracula's copyright, a great-grandnephew of Bram Stoker, Canadian writer Dacre Stoker, with encouragement from screenwriter Ian Holt, decided to write "a sequel that bore the Stoker name" to "reestablish creative control over" the original novel. In 2009, Dracula: The Un-Dead was released, written by Dacre Stoker and Ian Holt. Both writers "based [their work] on Bram Stoker's own handwritten notes for characters and plot threads excised from the original edition" along with their own research for the sequel. This also marked Dacre Stoker's writing debut.[19][20]

In Spring 2012, Dacre Stoker in collaboration with Prof. Elizabeth Miller presented the "lost" Dublin Journal written by Bram Stoker, which had been kept by his great-grandson Noel Dobbs. Stoker's diary entries shed a light on the issues that concerned him before his London years. A remark about a boy who caught flies in a bottle might be a clue for the later development of the Renfield character in Dracula.[21]

In October 2012, a major exhibition of Stoker's life will open at The Little Museum of Dublin on St. Stephens' Green.

Bibliography

Novels

- The Primrose Path (1875)

- The Snake's Pass (1890)

- The Watter's Mou' (1895)

- The Shoulder of Shasta (1895)

- Dracula (1897)

- Miss Betty (1898)

- The Mystery of the Sea (1902)

- The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903)

- The Man (aka: The Gates of Life) (1905)

- Lady Athlyne (1908)

- The Lady of the Shroud (1909)

- The Lair of the White Worm (aka: The Garden of Evil) (1911)

Short story collections

- Under the Sunset (1881), comprising eight fairy tales for children.

- Snowbound: The Record of a Theatrical Touring Party (1908)

- Dracula's Guest and Other Weird Stories (1914)

Uncollected stories

- "The Bridal of Death" (alternate ending to The Jewel of Seven Stars)

- "Buried Treasures"

- "The Chain of Destiny"

- "The Crystal Cup"

- "The Dualitists; or, The Death Doom of the Double Born"

- "Lord Castleton Explains" (chapter 10 of The Fate of Fenella)

- "The Gombeen Man" (chapter 3 of The Snake's Pass)

- "In the Valley of the Shadow"

- "The Man from Shorrox"

- "Midnight Tales"

- "The Red Stockade"

- "The Seer" (chapters 1 and 2 of The Mystery of the Sea)

Non-fiction

- The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879)

- A Glimpse of America (1886)

- Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (1906)

- Famous Impostors (1910)

- Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition (2008) Bram Stoker Annotated and Transcribed by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller, Foreword by Michael Barsanti. Jefferson NC & London: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3410-7

Critical works on Stoker

- William Hughes, Beyond Dracula (Palgrave, 2000) ISBN 0-312-23136-9 [22]

- Belford, Barbara. Bram Stoker. A Biography of the Author of Dracula. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1996.

- Senf, Carol. Science and Social Science in Bram Stoker's Fiction (Greenwood, 2002).

- Senf, Carol. Dracula: Between Tradition and Modernism (Twayne, 1998).

- Senf, Carol A. Bram Stoker (University of Wales Press, 2010).

References and notes

- ^ Belford, Barbara (2002). Bram Stoker and the Man Who Was Dracula. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-306-81098-0.

- ^ Note, as location has led to multiple edits: The location was, and is, in the Civil Parish of Clontarf. Clontarf extends to the east side of the Malahide Road and borders Marino. Fairview is further west commencing just after Marino Mart.

- ^ His siblings were: Sir (William) Thornley Stoker, born in 1845; Mathilda, born 1846; Thomas, born 1850; Richard, born 1852; Margaret, born 1854; and George, born 1855

- ^ a b c d Obituary, Irish Times, 23 April 1912

- ^ Website, Dublin Painting and Sketching Club, http://www.dublinpaintingandsketchingclub.ie/history.html

- ^ Irish Times, 8 March 1882, page 5

- ^ "Why Dracula never loses his bite". Irish Times. last modified 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Encyclopedia of World Biography, Gale Research (1998) vol 8. pgs. 461-464

- ^ a b Latham, Robert. Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review Annual, Greenwood Publishing (1988) p. 67

- ^ Zanger, Jules. Blood Read: The Vampire as Metaphor in Contemporary Culture ed. Joan Gordon. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press (1997), pgs. 17-24

- ^ What a Tax Lawyer Dug Up on 'Dracula'

- ^ Boylan, Henry (1998). A Dictionary of Irish Biography, 3rd Edition. Dublin: Gill and MacMillan. p. 412. ISBN 0-7171-2945-4.

- ^ "Bram Stoker". Victorian Web. last modified 1998. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gibson, Peter (1985). The Capital Companion. Webb & Bower. pp. 365–366. ISBN 0-86350-042-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Murray, Paul. From the Shadow of Dracula: A Life of Bram Stoker. 2004.

- ^ "Shadowplay Pagan and Magick webzine - HERMETIC HORRORS". Shadowplayzine.com. 16 September 1904. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Ravenscroft, Trevor (1982). The occult power behind the spear which pierced the side of Christ. Red Wheel. pp. p165. ISBN 0-87728-547-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Picknett, Lynn (2004). The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ. Simon and Schuster. pp. p201. ISBN 0-7432-7325-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Dracula: The Un-Dead by Dacre Stoker and Ian Holt

- '^ Dracula: The Undeads overview

- ^ Stoker, Bram. Bram Stoker’s Lost Dublin Journal, ed. by Stoker, Dacre and Miller, Elizabeth. London: Biteback Press, 2012

- ^ http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/victorian_studies/v044/44.2glover.html

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Bram Stoker at IMDb

- h2g2 article on Bram Stoker

- Bram Stoker's brief biography and works

- 20 Common Misconceptions and Other Miscellaneous Information

- The Stoker Dracula Organisation

- Gothic and Stoker Studies at Bath Spa University

Online texts

- Works by Bram Stoker at Project Gutenberg Full text versions of some of Stoker's novels.

- Bram Stoker Online Full text and PDF versions of most of Stoker's works.

- Bram Stoker's Dracula Full text of Stoker's novel Dracula.

- Works by Bram Stoker at Open Library

- Use dmy dates from May 2012

- Bram Stoker

- Dracula

- 1847 births

- 1912 deaths

- 19th-century Irish people

- Irish novelists

- Irish horror writers

- Irish short story writers

- Irish Anglicans

- Alumni of Trinity College, Dublin

- Former officers of the University Philosophical Society

- People from County Dublin

- People from Ballyshannon