History of the Cleveland Browns: Difference between revisions

m Removing "Patshurmur1.jpg", it has been deleted from Commons by Fastily because: Per commons:Commons:Deletion requests/File:Patshurmur1.jpg. |

|||

| Line 286: | Line 286: | ||

On September 6, Art Modell died in Baltimore at the age of 87. Although the Browns planned to have a moment of silence on their home opener for their former owner, his family asked the team not to, well aware of the less-than-friendly reaction it was likely to get. |

On September 6, Art Modell died in Baltimore at the age of 87. Although the Browns planned to have a moment of silence on their home opener for their former owner, his family asked the team not to, well aware of the less-than-friendly reaction it was likely to get. |

||

With Brandon Weeden taking the field, the Browns appeared to be headed for yet another dismal season. The 28-year old rookie QB threw four interceptions in a 17-16 loss to Philadelphia, |

With Brandon Weeden taking the field, the Browns appeared to be headed for yet another dismal season. The 28-year old rookie QB threw four interceptions in a 17-16 loss to Philadelphia, in which the Browns' only touchdown was scored by the defense. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 17:03, 25 September 2012

The history of the Cleveland Browns American football team began in 1944 when taxi-cab magnate Arthur B. "Mickey" McBride secured a Cleveland, Ohio franchise in the newly formed All-America Football Conference (AAFC). Paul Brown, who coach Bill Walsh once called the "father of modern football",[1] was the team's namesake and first coach. From the beginning of play in 1946 at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, the Browns were a great success. Cleveland won each of the AAFC's four championship games before the league dissolved in 1949. The team then moved to the more established National Football League (NFL), where it continued to dominate. Between 1950 and 1955, Cleveland reached the NFL championship game every year, winning three times.

McBride and his partners sold the team to a group of Cleveland businessmen in 1953 for a then-unheard-of $600,000. Eight years later, the team was sold again, this time to a group led by New York advertising executive Art Modell. Modell fired Brown before the 1963 season, but the team continued to win behind running back Jim Brown. The Browns won the championship in 1964 and reached the title game the following season, losing to the Green Bay Packers. The team subsequently reached the playoffs three times in the late 1960s, but fell short of playing in the Super Bowl, the inter-league championship game between the NFL and the rival American Football League (AFL) that started in 1966.

When the AFL and NFL merged before the 1970 season, Cleveland became part of the new American Football Conference (AFC). While the Browns made it back to the playoffs in 1971 and 1972, they fell into mediocrity through the mid-1970s. A revival of sorts took place in 1979 and 1980, when quarterback Brian Sipe engineered a series of last-minute wins and the Browns came to be called the "Kardiac Kids". Under Sipe, however, the Browns did not make it past the first round of the playoffs. Quarterback Bernie Kosar, who the Browns drafted in 1985, led the team to three AFC Championship games in the late 1980s but lost each time. In 1995, Modell announced he was relocating the Browns to Baltimore, sowing a mix of outrage and bitterness among Cleveland's dedicated fan base. Negotiations and legal battles led to an agreement where Modell was allowed to move the team, but Cleveland kept the Browns' name, colors and history. After three years of suspension while the old municipal stadium was demolished and Cleveland Browns Stadium took its place, the Browns started play again in 1999 under new owner Al Lerner. Since resuming operations, the Browns have made the playoffs only once, as a wild-card team in 2002.

Founding and dominance in the AAFC (1946–1949)

In 1944 Arch Ward, the influential sports editor of the Chicago Tribune, proposed a new professional football league called the All-America Football Conference.[3] The AAFC was to challenge the dominant National Football League once it began operations at the end of World War II, which had forced many professional teams to curtail activity, merge or go on hiatus as their players served in the U.S. military.[4] It was a bold proposition, given the failure of three previous NFL competitors and the dominance of college football, which was more popular than the professional game at the time.[5] Ward, who had gained fame and respect for starting all-star games for baseball and college football, lined up deep-pocketed owners for the new league's eight teams in hopes of giving it a better chance against the NFL.[6] One of them was Arthur B. "Mickey" McBride, a Cleveland businessman who grew up in Chicago and knew Ward from his involvement in the newspaper business.[7] McBride spent his early career as a circulation manager for the Cleveland News, and went into business for himself in the 1930s, buying a pair of Cleveland taxi companies and running a wire service that supplied bookies with information about the results of horse races.[7] He had connections to organized crime in Chicago and Cleveland arising from the wire service.[7][8]

McBride developed a passion for football attending games at Notre Dame, where his son went to college.[9] In the early 1940s he tried to buy the NFL's Cleveland Rams, owned by millionaire supermarket heir Dan Reeves, but was rebuffed.[9] Having been awarded the Cleveland franchise in the AAFC, McBride asked Cleveland Plain Dealer sportswriter John Dietrich for head coaching suggestions.[10] Dietrich recommended Paul Brown, the 36-year-old Ohio State Buckeyes coach.[10] After consulting with Ward, McBride followed Dietrich's advice in early 1945, naming Brown head coach and giving him an ownership stake in the team and full control over player personnel.[7] Brown, who had built an impressive record as coach of a Massillon, Ohio high school team and brought the Buckeyes their first national championship, at the time was serving in the U.S. Navy and coached the football team at Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago.[11]

The name of the team was at first left up to Brown, who rejected calls for it to be christened the Browns.[12] McBride then held a contest to name the team in May 1945; "Cleveland Panthers" was the most popular choice, but Brown rejected it because it was the name of an earlier failed football team. "That old Panthers team failed," Brown said. "I want no part of that name."[13] In August, McBride gave in to popular demand and named the team the Browns, despite Paul Brown's objections.[14]

As the war began to wind down with Germany's surrender in May 1945, the team parlayed Brown's ties to college football and the military to build its roster.[15] The first signing was Otto Graham, a former star quarterback at Northwestern University who was then serving in the Navy.[16] The Browns later signed kicker and offensive tackle Lou Groza and wide receivers Dante Lavelli and Mac Speedie.[17] Fullback Marion Motley and nose tackle Bill Willis, two of the earliest African-Americans to play professional football, also joined the team in 1946.[18] Cleveland's first training camp took place at Bowling Green University in northwestern Ohio.[19] Brown's reputation for winning notwithstanding, joining the team was a risk; the Browns and the AAFC were nascent entities and faced tough competition from the NFL. "I just went up there to see what would happen," center Frank Gatski said many years later.[19]

Cleveland's first regular-season game took place September 6, 1946 at Cleveland Municipal Stadium against the Miami Seahawks before a then-record crowd of 60,135.[21] That contest, which the Browns won 44–0, kicked off an era of dominance. With Brown at the helm, the team won all four of the AAFC's championships from 1946 until its dissolution in 1949, amassing a record of 52 wins, four losses and three ties.[22] This included the 1948 season, in which the Browns became the first unbeaten and untied team in professional football history.[23] The Browns had few worthy rivals among the AAFC's eight teams, but the New York Yankees and San Francisco 49ers were their closest competition.[24]

While the Browns excelled on defense, Cleveland's winning ways were driven by an offense that employed Brown's version of the T formation, which emphasized speed, timing and execution over set plays.[24] Brown liked his players "lean and hungry," and championed quickness over bulk.[2] Graham became a star under Brown's system, leading all passers in each of the AAFC's seasons and racking up 10,085 passing yards.[25] Motley, who Brown in 1948 called "the greatest fullback that ever lived",[26] was the AAFC's all-time leading rusher.[27] Brown and six players from the Browns' AAFC years were later elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame: Graham, Motley, Groza, Lavelli, Willis and Gatski.[28]

The Cleveland area showered support on the Browns from the outset.[29] Meanwhile, the Browns unexpectedly had Cleveland to themselves; the NFL's Cleveland Rams, who had continually lost money despite winning the 1945 NFL championship, moved to Los Angeles after that season.[30] The Browns' on-field feats only amplified their popularity, and the team saw average attendance of 57,000 per game in its first season.[31] The Browns, however, became victims of their own success. Cleveland's dominance exposed a lack of balance among AAFC teams, which the league tried to correct by sending Browns players including quarterback Y.A. Tittle to the Baltimore Colts in 1948.[32] Attendance at Browns games fell in later years as fans lost interest in lopsided victories, while attendance for less successful teams fell even more precipitously.[33] The Browns led all of football during the undefeated season in 1948 with an average crowd of 45,517, but that was more than 10,000 less than the average per game the previous year.[34] These factors – combined with a war for players between the two leagues that raised salaries and ate into owners' profits – ultimately led to the dissolution of the AAFC and the merger of three of its teams, including the Browns, into the NFL in 1949.[22] The NFL does not acknowledge AAFC statistics and records because these achievements – including the Browns' perfect season – did not take place in the NFL or against NFL teams, and not even in a league fully absorbed by the NFL.[35]

Success and challenges in the NFL (1950–1956)

The AAFC proposed match-ups with NFL teams numerous times during its four-year existence, but no inter-league game ever materialized.[36] That made Cleveland's entry into the NFL in the 1950 season the first test of whether its early supremacy could carry over into a more established league.[37] The proof came quickly: Cleveland's NFL regular-season opener was against the two-time defending champion Philadelphia Eagles on September 16 in Philadelphia.[38] The Browns quashed any doubt about their prowess in that game as Graham and his receivers amassed 246 passing yards in a 35–10 win before a crowd of 71,237.[39] Behind an offense that featured Graham, Groza, Motley, Lavelli and running back Dub Jones, Cleveland finished the 1950 season with a 10–2 record, tied for first place in the eastern conference.[40] After winning a playoff game against the New York Giants, the Browns advanced to the NFL championship match against the Los Angeles Rams in Cleveland. The Browns won 30–28 on a last-minute Groza field goal.[41] Fans stormed the field after the victory, carting off the goalposts, ripping off one player's jersey and setting a bonfire in the bleachers.[42] "It was the greatest game I ever saw," Brown later said.[43]

Show me another guy who toes a

Football as neatly as Lou Groza

– Doggerel signed "Hoosier Pick," 1946.

Groza's nickname was "The Toe."[44]

After five straight championship wins in the AAFC and NFL, the Browns appeared poised to bring another trophy home in 1951. The team finished the regular season with 11 wins and a single loss in the first game of the season.[45] Cleveland faced the Rams on December 23 in a rematch of the previous year's title game.[46] The score was deadlocked 17–17 in the final period, but a 73-yard touchdown pass by Rams quarterback Norm van Brocklin to wide receiver Tom Fears broke the tie and gave Los Angeles the lead for good. The 24–17 loss was the Browns' first in a championship game.[47]

The 1952 and 1953 seasons followed a similar pattern: Cleveland reached the championship game but lost both times to the Detroit Lions.[48] In 1952's championship game, Detroit won 17–7 after a muffed punt by the Browns, several Lions defensive stands and a 67-yard touchdown run by Doak Walker scuttled Cleveland's chances.[49] The team finished 11–1 in 1953, but lost the championship to the Lions 17–16 on a 33-yard Bobby Layne touchdown pass to Jim Doran with just over two minutes left.[50] While the championship losses disappointed Cleveland fans who had grown accustomed to winning, the team continued to make progress. Len Ford, who the Browns picked up from the defunct AAFC's Los Angeles Dons team, emerged as a force on the defensive line, making the Pro Bowl each year between 1951 and 1953.[51] Second-year wideout Ray Renfro became a star in 1953, also reaching the Pro Bowl.[52]

During the summer before the 1953 season, the Browns' original owners sold the team for a then-unheard-of $600,000.[54] The buyers were a group of prominent Cleveland men: Dave R. Jones, a businessman and former Cleveland Indians director, Ellis Ryan, a former Indians president, Homer Marshman, an attorney, and Saul Silberman, owner of the Randall Park race track.[55] McBride had been called in 1950 to testify before the Kefauver Committee, a congressional body investigating organized crime, which partly exposed his ties to mafia figures but did not result in any charges.[54] While McBride never said so, the Kefauver hearings and the growing public association between him and the mafia may have played a role in his decision to get out of football.[8]

While the Browns came into 1954 as one of the top teams in the NFL, the future was far from certain. Graham, whose leadership and throwing skills were instrumental in the Browns' championship runs, said he planned to retire after the season.[56] Motley, the team's best rusher and blocker, retired at the beginning of the season with a bad knee.[57] Star defensive lineman Bill Willis also retired before the season.[57] Still, Cleveland finished the regular season 9–3[58] and met Detroit the day after Christmas in the championship game for a third consecutive time.[59] And this time Cleveland dominated on both sides of the ball, intercepting Bobby Layne six times while Graham threw three touchdowns and ran for three more.[59] The Browns, who lost the last game of the regular season to the Lions only a week before, won their second NFL crown 56–10.[59] "I saw it, but still hardly can believe it," Lions coach Buddy Parker said after the game. "It has me dazed."[60]

Cleveland's success continued in 1955 after Brown convinced Graham to come back, arguing that the team lacked a solid alternative.[61] Cleveland finished the regular season 9–2–1 and went on to win its third NFL championship, beating the Los Angeles Rams 38–14.[62] It was Graham's last game; the win capped a 10-year run in which he led his team to the league championship every year, winning four in the AAFC and three in the NFL.[63] Rams fans gave Graham a standing ovation when Brown pulled him from the game in the final minutes.[64]

Without Graham, the Browns floundered in 1956.[65] Injuries to two Browns quarterbacks left relative unknown Tommy O'Connell as the starter, and Cleveland finished with a 5–7 record, its first losing season.[66] Dante Lavelli and Frank Gatski retired at the end of the season, leaving Groza as the only original Browns player still on the team.[65] While the Browns' on-field play in 1956 was uninspiring, off-the-field drama developed after a Cleveland-based inventor let Brown test a helmet with a radio transmitter inside.[66] After trying it out in training camp, Brown used the helmet to call plays during the pre-season with long-time backup George Ratterman behind center. The device allowed the coach to direct his quarterback on the fly, giving him an advantage over franchises who had to use messenger players to relay instructions.[67] The Browns used the device off and on into the regular season, and other teams began to experiment with their own radio helmets.[68] Bert Bell, the NFL commissioner, banned the device in October 1956.[69] Today, however, all NFL teams use in-helmet radios to communicate with players.[70]

Jim Brown era and new ownership (1957–1965)

With Otto Graham and most of the other original Browns in retirement, by 1957 the team was struggling to replenish its ranks.[71] In the first round of that year's draft, Cleveland took fullback Jim Brown out of Syracuse University.[72] In his first season, Brown led the NFL with 942 yards of rushing and was voted rookie of the year in a United Press poll.[73] Cleveland finished 9–2–1 and again advanced to the championship game against Detroit. The Lions dominated the game, forcing six turnovers and allowing only 112 yards passing in a 59–14 rout.[74]

Before the 1958 season, O'Connell, who lacked the stature and durability Paul Brown wanted in a starter, retired to take a coaching job in Illinois, and Milt Plum was named as his replacement.[75][76] Cleveland, however, was relying increasingly on the running game, in contrast to its pass-happy early years under Graham. As the team built up a 9–3 regular-season record, Brown in 1958 ran for 1,527 yards – almost twice as much as any other back and a league record at the time.[77]

Entering the final game of the 1958 season, Cleveland needed to either win or tie against the New York Giants to clinch the Eastern Conference title and the right to host the championship game.[78] Cleveland lost that game under snowy conditions on a 49-yard field goal by Pat Summerall as time expired, and then lost a playoff game against the Giants the following week to end the season.[79][80] The Giants went on to play the Baltimore Colts in the championship, a game often cited as the seed of professional football's popularity surge in the U.S.[81]

Cleveland's campaigns in 1959 and 1960 were unremarkable, aside from Brown's league-leading rushing totals in both seasons.[82] Plum, meanwhile, became the established starting quarterback, bringing a measure of stability to the squad not seen since Graham's retirement. He led the team to a 7–5 record in 1959 and an 8–3–1 record in 1960, but neither was good enough to win the Eastern Conference and advance to the championship.[83][84] Behind the scenes, however, all was not well. A conflict took shape between Paul Brown and Jim Brown; emboldened by his success, the fullback began to question his coach's disciplinarian methods. He called the coach "Little Caesar" behind his back. At halftime during a game in 1959, Paul Brown questioned the severity of an injury Jim Brown was sidelined for, which further inflamed tensions between the two.[85]

Art Modell takes ownership

Fred "Curly" Morrison, a former Browns running back who worked as an advertising executive for CBS television, learned in 1960 that Dave Jones was looking to sell the Browns and told the story to Art Modell, a 35-year-old advertising and television executive from Brooklyn.[86] Modell was intrigued, partly because of the potentially lucrative television rights that one of the NFL's most successful franchises could bring as football began to challenge baseball as America's biggest sport.[87] Having borrowed as much money as he could, Modell completed the purchase in March 1961 for $3.925 million. Bob Gries, who had a share in the Browns from the beginning, agreed to buy in again at the new valuation and take a stake of almost 40%, defraying Modell's costs substantially.[88] As the previous owners did when they took over, Modell quickly assured Cleveland fans that Brown would "have a free hand" in running the organization and awarded him a new eight-year contract.[89] "As far as I'm concerned Paul Brown can send [plays] in by carrier pigeon," Modell said. "In my opinion he has no peer as a football coach. His record speaks for itself. I view our relationship as a working partnership."[90]

The 1961 season was typical on the field: Jim Brown led the league in rushing for the fifth straight season and the team ended with an 8–5–1 record. That left Cleveland two games out of a berth in the championship.[91] During that year, however, players began to question Paul Brown's strict and often overbearing demeanor, while many challenged his control over the team's strategy. Milt Plum spoke out against Brown calling all the team's offensive plays, and Jim Brown said on a weekly radio broadcast that the coach's play-calling and handling of Plum were undermining the quarterback's confidence.[92][93] They found a willing listener in Modell, a bachelor who was closer to their age than the coach's.[94]

Further cracks appeared in the "working partnership" between Paul Brown and Modell before the 1962 season. Brown made a trade without informing Modell, giving up star halfback Bobby Mitchell to acquire the rights to Syracuse running back Ernie Davis, the first African-American to win the Heisman Trophy.[91] Davis was chosen by the Washington Redskins with the first overall pick in the 1962 draft, but while Davis was the first black player ever selected by Washington, team owner George Preston Marshall made the move only after being given an ultimatum to add an African-American player or risk losing his stadium lease. Davis demanded a trade, leaving the door open to the Browns, who signed him to a three-year contract worth $80,000.[95] As Davis was preparing for the College All-Star Game, however, he came down with a mystery illness and was later diagnosed with leukemia. Brown ruled Davis out for the season, but the running back returned to Cleveland and began a conditioning program after one of his doctors said playing football would not exacerbate his condition.[96] Modell thought Davis could be prepared to play, and Davis, who by then knew he was dying, wanted to be part of the team. Brown, however, continued to insist that he sit out, driving a deeper wedge between him and Modell. Davis died the following May.[97]

The rift between Brown and Modell only widened as the 1962 season progressed. Frank Ryan took Milt Plum's place as the team's starting quarterback by the end of the season, and the Browns finished with a 7–6–1 record. Jim Brown was not the NFL's leading rusher for the only time in his career.[98]

Paul Brown is fired

On January 9, 1963, Art Modell sent a statement to the newswires: "Paul E. Brown, head coach and general manager, will no longer serve the team in those capacities," it said.[99] Immediate reaction to the decision was muted due to a newspaper strike that kept the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Cleveland Press off the newsstands until April. A printing company executive, however, got together a group of sportswriters and published a 32-page magazine fielding players' views on the firing. Opinions were mixed; Modell came in for his share of criticism, but tackle and team captain Mike McCormack said he did not think the team could win under Brown.[100] Nonetheless, it was a shocking end to the 17-year Cleveland career of a coach who was already a seminal figure in the city's sports history.[101] Among many innovations, Brown was the first coach to call plays for his quarterback, give players IQ and personality tests and use game film to evaluate opponents.[102] Even Jim Brown lauded his pioneering role in integrating the game:

Paul Brown integrated pro football without uttering a single word about integration. He just went out, signed a bunch of great black athletes, and started kicking butt. That's how you do it. You don't talk about it. ... [I]n his own way, the man integrated football the right way – and no one was going to stop him.[103]

Modell named Brown's chief assistant, Blanton Collier, as the team's new head coach.[104] Collier was a friendly, studious man who became a player favorite as an assistant on both offense and defense under Brown.[105] He installed an open offense and allowed Ryan to call his own plays.[106] In Collier's first season, the Browns finished with a 10–4 record but fell short of a division title.[107] Jim Brown won the MVP award in 1963 with a record 1,863 yards rushing. Dominant blocking from the Browns' offensive line, which included guard Gene Hickerson and left tackle Dick Schafrath, helped boost his totals.[108]

1964 championship

Cleveland climbed back to the top of the eastern division in 1964 with a 10–3–1 record behind Jim Brown's league-leading 1,446 yards of rushing.[109] Rookie wide receiver Paul Warfield led the team with 52 catches,[110] and Frank Ryan cemented his place as the team's starting quarterback, recording the best game of his career in the season closer against the New York Giants – a game the Browns needed to win to advance to the championship.[111] Yet despite Cleveland's prowess, the Browns went into the championship game as heavy underdogs against the Baltimore Colts. Most sportswriters predicted an easy win for the Colts, who led the league in scoring behind quarterback Johnny Unitas and halfback Lenny Moore. The Browns' defense, moreover, was suspect. The team gave up 20 more first downs than any other in the league.[112] The teams, however, had not faced each other for three years. Before the game, Collier and Colts coach Don Shula agreed to give each other full access to video of regular-season games. Ever the student, Collier took full advantage of the opportunity. The Browns had run what was dubbed a "rubber band" pass defense, allowing short throws while trying to prevent big plays. The Colts' top receivers, however, Raymond Berry and Jimmy Orr, were not fast. They tended to pick apart defenses with short, tactical completions, which led Collier to institute a man-to-man pass defense for the game. This, he figured, would buy more time for the defensive line and force Unitas to scramble — not his forte.[113]

The strategy paid off, and in the wind-whipped Cleveland Municipal Stadium two days after Christmas, the Browns beat the Colts 27–0. Neither team scored in the first half, prompting New York Times columnist Red Smith to quip, "Never have so many paid so dearly – $10, $8, and $6 – and suffered so sorely to see so little."[114] In the second half, the Browns' defense held on and the offense kicked into gear. Baltimore's cornerbacks were double-teaming Warfield, which Ryan exploited by throwing three touchdowns to his second wideout, Gary Collins. The Browns scored 10 points in the third quarter and a further 17 in the fourth, clinching the first title since Otto Graham's departure after the 1955 season.[115] Collins was named the game's MVP.[116]

The following year was a strong one as Jim Brown gritted out another league-leading rushing season.[117] The Browns ended with an 11–3 record and comfortably won the eastern division.[118] That set up a second straight appearance in the NFL Championship game in frozen Green Bay against the Packers. The teams battled it out on a slippery, mucky Lambeau Field on January 2, 1966. While score was close early on, Vince Lombardi's team held the Browns scoreless in the second half, winning 23–12 in an upset on a Paul Hornung touchdown.[119] After the season, the NFL and the competing American Football League agreed to merge starting in 1970, but would play an inter-league championship from the 1966 season onward. The 1965 championship thus became the NFL's last before the Super Bowl era, which ushered in a new age of popularity and prosperity for professional football.

In time, this game would be nearly forgotten, lost in the middle of Lombardi's great triumphs. ... This was both unfair and fitting in a sense, because the game was best considered on its own, a faded dream played in the mist and slop, a transitory moment between football past and future.

— David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi[120]

Playoff disappointments (1966–1973)

Jim Brown goes to Hollywood

Jim Brown began an acting career before the 1964 season, playing a Buffalo Soldier in a western action film called Rio Conchos.[121] The film premiered at Cleveland's Hippodrome theater on October 23, with Brown and many of his teammates in attendance. The reaction was lukewarm. Brown, one reviewer said, was a serviceable actor, but the movie's overcooked plotting and implausibility amounted to "a vigorous melodrama for the unsqueamish."[122]

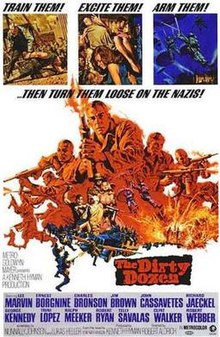

In early 1966 Brown, who had grown debonair and aloof as he rocketed to fame, was shooting for his second film in London.[123] The Dirty Dozen cast Brown as Robert Jefferson, a convict sent to France during World War II to assassinate German officers meeting at a castle near Rennes in Brittany before the D-Day invasion. Production delays due to bad weather meant he would miss at least the first part of training camp on the campus of Hiram College, which annoyed Modell, who threatened to fine Brown $1,500 for every week of camp he missed.[124] Brown, who had previously said that 1966 would be his last season, announced his retirement instead.[121] At the end of his nine-year career, Brown held records for most rushing yards in a game, a season and a career. He also owned the record for all-purpose yards in a career and best average per carry for a running back at 5.22 yards, a mark that still stands.[125]

With Brown gone, halfback Leroy Kelly became the team's new rushing threat in 1966. Kelly, an eighth-round draft choice who saw limited playing time in two years as a backup, ably filled his predecessor's shoes.[126] Cleveland missed the playoffs in 1966, but made it to the postseason the following year after a realignment of the NFL's divisions that placed the Browns in the new Century Division.[127] The Browns, however, lost the 1967 eastern conference championship to the Dallas Cowboys.[127] After a year in which he made just 11 of 23 field goal attempts, placekicker Lou Groza retired before the start of the 1968 season.[128] Groza, who had been on the roster for 21 seasons and was 44 years old when he hung up his spikes, said in his memoir that retiring was "the saddest day of my football life."[129]

Further playoff defeats followed. In 1968, as a 32-year-old Ryan was benched in favor of Bill Nelsen,[130] the Browns finished with a 10–4 record but lost to the Colts in the playoffs.[131] Another playoff loss ended the Browns' season in 1969, this time to the Minnesota Vikings.[132] After the American Football League's merger with the NFL was finalized in early 1970, the Browns, Pittsburgh Steelers and Baltimore Colts moved to the new American Football Conference along with the 10 teams of the former AFL. The Browns were slotted in the AFC Central in the 26-team league, alongside the Steelers, the Houston Oilers and the Cincinnati Bengals, a team Paul Brown founded in 1968 in the AFL.[133] Cleveland's first big move under the new league structure was to trade star receiver Paul Warfield in January 1970 to the Miami Dolphins for the rights to draft Purdue University quarterback Mike Phipps as a replacement for Bill Nelsen, who had a pair of bad knees.[134][135]

The Browns opened the 1970 season by beating Joe Namath and the New York Jets in the first-ever broadcast of Monday Night Football on September 21.[136] The following month, Cleveland faced Paul Brown's Bengals for the first time in a regular-season game, winning 30–27. That game was a highlight in an otherwise unsuccessful season. The Browns lost to the Bengals 14–10 in November, when Phipps made his first start — Brown called it "my greatest victory" — and finished 7–7.[137]

Plagued by hearing problems, the 64-year-old Collier announced his retirement before the end of the 1970 season.[138] In eight years as coach, Collier led Cleveland to a championship and a 74–33–2 record.[139] Nick Skorich was named as his replacement the following year.[134] Skorich came to the Browns as offensive coordinator in 1964, when the team won the championship.[134] In Cleveland's first year under Skorich, the team improved to 9–5 but lost to the Colts in a divisional playoff.[140] Mike Phipps was promoted to starting quarterback over Nelsen before the 1972 season.[140] After a sluggish start, the Browns went on tear and finished with a 10–4 record. That put Cleveland in a playoff against the undefeated Miami Dolphins. The Browns took a lead in the fourth quarter on a touchdown catch by wide receiver Fair Hooker, but the Dolphins responded with a long drive of their own, aided by a pair of Paul Warfield receptions. Running back Jim Kiick ran for a touchdown, sealing a 20–14 win and preserving the Dolphins' perfect season.[141] The following year, Phipps threw 20 interceptions and completed less than half of his passes.[141] After winning four of the first six games, the Browns slumped and placed third in the division with a 7–5–2 record.[141]

Brian Sipe era and the Kardiac Kids (1974–1984)

Transition and poor play marked the mid- to late-1970s. Though Collier agreed to come back to the Browns as a quarterbacks coach on an informal basis, his retirement severed the last direct link to Brown and the team's early years.[142] Meanwhile, a new generation of players began to replace the old hands who kept Cleveland in playoff contention through most of the 1960s. Gene Hickerson, an anchor on the offensive line in the 1960s, retired at the end of the 1973 season.[143] An aging Leroy Kelly, Jim Brown's surprisingly successful replacement in the backfield, left the same year to play in the short-lived World Football League.[144] Offensive lineman Dick Schafrath, a six-time Pro Bowl selection, retired in 1971.[145]

Against that backdrop, the Browns finished the 1974 season with a 4–10 record, only the second losing season in the team's history.[141] Phipps' woes persisted, and he shared playing time with rookie quarterback Brian Sipe, who Cleveland selected in the 13th round of the 1972 draft out of San Diego State.[146] Modell fired Skorich after the season. "You've got to be a winner in this game, and I just didn't produce," Skorich said at the time.[147] After pursuing Dolphins offensive line coach Monte Clark, Modell hired Forrest Gregg as Skorch's replacement.[148] Gregg, an assistant coach and former Green Bay Packers offensive lineman, preached a hard-nosed, physical brand of football, learned as an offensive lineman on Green Bay's dynastic 1960s teams under Lombardi.[149] His success as a player, however, did not immediately translate into success as a coach. The regular season began with the worst losing streak in Cleveland's history. Gregg's first win did not come until November 23 against Paul Brown's Cincinnati Bengals, and Cleveland finished with a 3–11 record.[150]

The team improved the following year, ending with a 9–5 record but missing the playoffs.[151] The highlight of that season was an 18–16 victory over the Pittsburgh Steelers on October 10.[150] Kicker Don Cockroft booted four field goals, while defensive end Joe "Turkey" Jones' pile-driving sack of quarterback Terry Bradshaw added fuel to the heated rivalry between the teams.[152] While Gregg won the NFL's Coach of the Year award for turning the Browns around as Sipe became the starting quarterback, by the beginning of the 1977 season the same kind of friction that dogged Paul Brown's relationship with Modell was surfacing between the owner and the hotheaded Gregg.[153] Cleveland got off to a strong start that year, but Sipe hurt his shoulder and elbow in a November 13 game against the Steelers, and backup Dave Mays took the reins.[151] With Mays as the quarterback – Modell traded Phipps to the Chicago Bears for a couple of draft picks – Cleveland slipped to 6–7 going into the final game of the season and Modell asked Gregg to resign.[154]

Modell said he would look outside the Browns organization for a new coach, a break from past hirings that drew from the team's own ranks.[155] Peter Hadhazy, who Modell had hired as the Browns' first general manager, recommended a 45-year-old New Orleans Saints receivers coach named Sam Rutigliano. After an interview before Christmas in which Modell and Rutigliano spent hours talking and watching game film in Modell's basement, the owner named him head coach on December 27, 1977.[155] An affable, charismatic man with an even temper, Rutigliano was a stark contrast to Gregg.[156] Sipe immediately flourished under Rutigliano, racking up 21 touchdowns and 2,906 passing yards during the 1978 season, when the NFL moved to a 16-game schedule.[151] His prime targets were Reggie Rucker, a veteran receiver the Browns signed in 1975, and Ozzie Newsome, a rookie tight end out of Alabama who the Browns drafted with a pick acquired in the Phipps trade.[157] Cleveland won its first three games, but poor defense dashed the team's playoff chances and the Browns finished with an 8–8 record.[158]

Kardiac Kids

Rutigliano was a gambler: he tinkered with offenses, took chances on trick plays and was not afraid to break with the play-calling conventions of his time.[159] The coach, who earned the nickname "Riverboat Sam" for his risk-taking approach, once said that security was "for cowards". "I believe in gambling," he said. "No successful man ever got anywhere without gambling."[160] This seat-of-your-pants philosophy began to manifest itself on the field in 1979. The campaign started with a nail-biter against the New York Jets that the Browns won in overtime on a Cockroft field goal as time expired. "If we continue to play 'em that way all year, I'll be gone before the 10th game because my heart just won't take it," Rutigliano said after the game.[161] In the second week, Cleveland beat the Kansas City Chiefs 27–24 on a Sipe touchdown to Rucker with 52 seconds left.[162] The third game was an equally improbable 13–10 win against the Baltimore Colts.[162] Cleveland Plain Dealer sports editor Hal Lebovitz wrote after the game that these "Kardiac Kids" were lucky to have pulled off the win after Colts kicker Toni Linhart missed three field goals.[163]

After a string of four wins and three losses, the late-game heroics returned in an overtime victory on November 18 against the Miami Dolphins.[160] "You should never pipe Browns games into an intensive care unit, expose them to anyone weak of pulse," wrote Toledo Blade columnist Jim Taylor. "They're one of those teams that stands 8–4, and could easily be 1–11."[164] While the Browns' 9–7 record did not get the team into the playoffs – the defense struggled all year, forcing Sipe and the offense to compensate with late-game comebacks – a sense of optimism and excitement took hold.[165]

The Kardiac Kids magic returned in the third game of the next season against the Chiefs, when the Browns scored a touchdown in the fourth quarter to win 20–13.[166] More down-to-the-wire games followed, including one against Green Bay on October 19 in which the team won on a touchdown to receiver Dave Logan on the last play of the game.[167] After a close win over the Steelers and a victory over the Bears in which Sipe broke Otto Graham's club record for career passing yards, the Browns met the Colts and eked out a 28–27 win.[168] The team ended with a 11–5 record.[169]

Red Right 88

That was good for first place in the AFC Central and a trip to the postseason for the first time since 1972.[170] The playoffs began against the Oakland Raiders on January 4, 1981 in a bitterly cold Cleveland Municipal Stadium.[171] The game started slowly: each team scored only a touchdown in the first half, although Cockroft missed Cleveland's extra point because of a bad snap.[172] In the third quarter, Cleveland went ahead 12–7 on a pair of Cockroft field goals, but the Raiders came back in the final period, driving 80 yards down the field for a touchdown. That put Oakland ahead 14–12.[173] The ball changed hands five times with no scoring from either side, and with 2:22 on the clock, Cleveland had a final shot to win the game.[174] Sipe and the offense took over at the Browns' 15-yard line. In eight plays, Cleveland drove down to Oakland's 14, leaving 56 seconds on the clock.[175]

After a one-yard Mike Pruitt run, Rutigliano called a timeout.[175] A short field goal would have been the safe bet — that was all Cleveland needed to win. Rutigliano, ever the risk-taker, decided to go for a touchdown. The coach was reluctant to stake the game's outcome on the usually sure-footed Cockroft, who had missed two field goals and an extra point earlier in the game.[175] The play he called was Red Right 88, a passing formation in which a slanting Logan would be Sipe's primary target, while Newsome was insurance. If everyone was covered, Rutigliano told Sipe on the sidelines, "if you feel you have to force the ball, throw it into Lake Erie, throw it into some blonde's lap in the bleachers."[176] Sipe took the snap, dropped back and threw to Newsome as he crossed to the left. But Oakland safety Mike Davis leaped in front and intercepted the ball, cementing the Oakland win. The Raiders went on to win Super Bowl XIV, while Red Right 88 became an enduring symbol of Cleveland's postseason stumbles.[177]

Despite 1980's playoff defeat, the Browns were widely expected to be even better the following year. But 1981 came with none of the comebacks or late-game magic the Kardiac Kids were known for. Several games were close, but most were losses. Sipe threw only 17 touchdowns and was intercepted 25 times.[178] The team finished 5–11.[179] The 1982 NFL strike, which began in September and lasted until mid-November, shortened the regular season the following year to nine games.[180] Coming off a poor year, Sipe split starts with his backup, Paul McDonald, and neither was able to bring back the old Kardiac Kids spark.[180] The team ended with a 4–5 record, which qualified for an expanded Super Bowl playoff tournament created to accommodate the shorter season. The Browns faced the Raiders in a rematch of 1980's playoff thriller. This time, though, McDonald was the starter and the ending was far from tense. The Raiders won 27–10.[180]

The following two years brought the Sipe era and the short-lived success of the Kardiac Kids to an end.[181] Sipe returned to form in 1983, and the team narrowly missed a spot in the playoffs after a loss to the Houston Oilers in the second-to-last game of the regular season.[182] Sipe signed before the end of the season to play for the New Jersey Generals, a team owned by real estate mogul Donald Trump in the upstart United States Football League.[181]

In training camp before the 1984 season, cornerback Hanford Dixon tried to motivate the team's defensive linemen by barking at them between plays in practice and calling them "the Dogs". "You need guys who play like dogs up front, like dogs chasing a cat," Dixon said.[183] The media picked up on the name, which gained traction in part because of the improvement of the Browns' defense during the regular season. Fans put on face paint and dog masks, and the phenomenon coalesced in rowdy fans in Cleveland Stadium's cheap bleachers section close to the field.[183] The Dawg Pound, as the section was eventually nicknamed, is a continuing symbol of Cleveland's dedicated fan base.[184]

Despite the defensive improvement, Sipe's departure left Cleveland's offense in disarray in 1984. Browns began the season 1–7 with McDonald at quarterback, and fans' frustration with the team and Rutigliano boiled over.[182] The breaking point came in an October 7 game against the New England Patriots that bore an eerie resemblance to Cleveland's 1980 playoff loss to the Raiders. The Browns were down 17–16 in the fourth quarter, and lost on an interception in New England's end zone as time expired.[185] Chants of "Goodbye Sam" rung out from the stands after the New England game. Modell called the play-calling "inexcusable" and fired Rutigliano two weeks later.[186] Defensive coordinator Marty Schottenheimer took over, and the Browns ended with a 5–11 record.[187]

Bernie Kosar years, The Drive and The Fumble (1985–1990)

The selection of University of Miami quarterback Bernie Kosar in 1985's supplemental draft ushered in a new, largely successful era for Cleveland. With Schottenheimer, Kosar and a cast of talented players on offense and defense, the team reached greater heights than Rutigliano and Sipe ever did. Though they became consistent playoff contenders in this era, the Browns did not reach the Super Bowl, falling one win short three times in the late 1980s.[188]

Kosar, who wanted to play for Cleveland because his family lived in a suburb of nearby Youngstown, Ohio, signed a five-year contract worth nearly $6 million in 1985 and was immediately embraced by the Browns organization and the team's fans.[189] "It's not an everyday occurrence that somebody wants to play in Cleveland," Modell said. "This has lent such an aura to Bernie."[190] Kosar saw his first action in the fifth week of the 1985 season against the New England Patriots, when he substituted before halftime for Gary Danielson, a 34-year-old veteran who the Browns had acquired in the offseason from the Lions.[191] Kosar fumbled his first-ever NFL snap, but rebounded and led the team to a 24–20 win.[192] A mix of success and failure followed, but Kosar progressed a bit more each Sunday and led the team to an 8–8 record.[193] Two young running backs, Earnest Byner and Kevin Mack, complemented Kosar's aerial attack with more than 1,000 yards rushing each.[194]

While not stellar, the Browns' record won first place in a weak AFC Central, and the team looked poised to shock the heavily favored Miami Dolphins in a divisional playoff game on January 4, 1986.[195] Cleveland surged to a 21–3 halftime lead, and it took a spirited second-half comeback by Dan Marino and the Dolphins to win it 24–21 and end the Browns' season.[196] Despite the loss, many people expected Cleveland to be back the following year. "The Browns' days, the good days, are here and ahead of us," radio personality Pete Franklin said.[197]

The following year marked Cleveland's entry into the ranks of the NFL's elite as Kosar's play improved and the defensive unit came together. Kosar threw for 3,854 yards to a corps of receivers that included Brian Brennan, Newsome and rookie Webster Slaughter.[198] On defense, cornerbacks Frank Minnifield and Hanford Dixon emerged as one of the NFL's premiere pass-defending duos.[199] After a slow start, the Browns rose to the top of the divisional standings, twice beating the Pittsburgh Steelers and ending a 16-game losing streak at Three Rivers Stadium.[200] A 12–4 record earned Cleveland home-field advantage throughout the playoffs.[201]

The Browns' first opponents in the 1986 playoffs were the New York Jets.[202] The Jets were ahead for most of the game and held a 20–10 lead as time wound down in the final quarter. But Cleveland took over and began a march down the field, ending with a Kevin Mack touchdown.[203] The defense forced the Jets to punt after the ensuing kickoff, leaving the offense with less than a minute to get within field goal range and even the score at 20–20. A pass interference penalty and a completion to Slaughter put the ball at the Jets' five-yard line, and kicker Mark Moseley booted through the tying score with 11 seconds left.[204] In an initial 15-minute overtime period, Moseley missed a short field goal and neither team scored, sending the game into double overtime.[205] This time, Moseley made a field goal and won the game for the Browns 23–20. It was the team's first playoff victory in 18 years.[206]

The Drive

The following week, the Browns matched up against the Denver Broncos in the AFC Championship game in Cleveland.[207] Denver got out to an early lead, but Cleveland tied it and then went ahead 20–13 in the fourth quarter on a 48-yard touchdown pass to Brennan.[208] The Broncos muffed the ensuing kickoff and were pinned at their own two-yard line with just 5:34 remaining. Denver quarterback John Elway, who the Browns' defense had contained for most of the game, then engineered a 98-yard drive for a touchdown with the cold, whipping wind in his face as time expired.[209] "The Drive," as the series came to be known, tied the score and sent the game into overtime. Cleveland received the ball first in the sudden-death period, but was stopped by the Denver defense and forced to punt. On Denver's first possession, Elway again led the Broncos down the field, setting up a Rich Karlis field goal that sailed just inside the right upright and won the game.[210]

The drive that tied the game has since come to be seen as one of the best in playoff history, and is remembered by Cleveland fans as an historic meltdown. Denver went on to lose the Super Bowl to the New York Giants.[211]

The drive, one of the finest ever engineered in a championship game, had been performed directly in the Browns' faces. There was no sneakiness about it; John Elway had simply shown what a man with all the tools could do. It was what everybody who had watched him enter the league as perhaps the most heralded quarterback since Joe Namath knew he could do. One was left with the distinct feeling that Elway would have marched his team down a 200-yard-or 300-yard-or five-mile-long field to pay dirt.

— Rick Telander, Sports Illustrated[212]

Although downtrodden by 1986's playoff defeat, Cleveland continued to win the following season.[213] Minnifield and Dixon played havoc with opponents' passing attacks, while Matthews and defensive tackle Bob Golic kept runners in check.[214] The Browns finished with a 10–5 record and won the AFC Central for the second year in a row.[215] The divisional playoff round pitted the Browns against the Indianapolis Colts. The Browns led most of the game and won 38–21.[216]

The Fumble

The win set up a rematch with the Broncos in the AFC Championship in Denver.[217] The Broncos held a commanding 21–3 lead at halftime,[218] but a pair of third-quarter Earnest Byner touchdowns and another by receiver Reggie Langhorne brought the Browns to within seven points.[219] Early in the fourth quarter, Webster Slaughter's 4-yard touchdown catch tied the game at 31–31. Elway and the Broncos then went ahead with a 20-yard Sammy Winder touchdown with four minutes to go.[220] After Denver's kickoff, Kosar and the offense marched downfield, reaching the Brocos' eight-yard line with 1:12 left in the game.[221] Kosar handed the ball to Byner on a second down. Byner ran left and broke inside with a clear path to the end zone, but was stripped by Denver's Jeremiah Castille just before crossing the goal line. Having recovered the ball, the Broncos ran down the clock before intentionally taking a safety and winning 38–33.[222] "The Fumble" quickly entered the lexicon of the Browns' modern-era disappointment, just as The Drive had a year before.[215]

The 1988 season was marred by injuries to the Browns' quarterbacks. Kosar went down in the opener against Kansas City Chiefs and two backups were subsequently injured, leaving Don Strock, who the Browns signed as an emergency fill-in, to start before Kosar's return.[223] Kosar came back but was hurt again at the end of the regular season.[224] Despite the rotating cast of quarterbacks, Cleveland managed to finish with a 10–6 record and made the playoffs as a wild-card team.[225] Cleveland met the Houston Oilers in the wild-card playoff round at home, but lost the game 24–23.[226] Four days after the Oilers loss, Schottenheimer and Modell announced that the coach would leave the team by mutual consent. Modell felt hiring an offensive coordinator was necessary to keep pace with the Oilers and the Bengals, a pair of divisional opponents then on the rise,[227] but Schottenheimer said it "became evident that some of the differences we had, we weren't going to be able to resolve."[228] Modell named Bud Carson as his replacement.[229]

Carson, an architect of Pittsburgh's 1970s "Steel Curtain" defenses, made several changes to Cleveland's lineup.[230] Byner was traded to the Washington Redskins in April, while the Browns moved up in the draft to acquire Eric Metcalf.[231] Kevin Mack, meanwhile, was suspended for the first four games of the 1989 season after pleading guilty to cocaine possession.[232] Despite these changes, Kosar led Cleveland to a division-winning 9–6–1 record in 1989, including a season-opening 51–0 shutout of the rival Pittsburgh Steelers and the team's first victory over the Denver Broncos in 15 years.[233] Cleveland narrowly survived a scare from the Buffalo Bills in the first playoff game, staving off a comeback thanks to an interception in the Browns' end zone by Clay Matthews with 14 seconds on the clock.[234] The victory set up the third AFC championship matchup in four years between the Browns and Broncos. The Broncos led from start to finish, and a long Elway touchdown pass to Sammy Winder put the game way in the fourth quarter. Denver won 37–21.[235]

The defeat in Mile High Stadium proved to be the last of Cleveland's streak of playoff appearances in the mid- to late-1980s. Kosar played through numerous injuries in 1989, including bruising on his right arm and a bad knee.[236] Strong defense had carried the Browns to the playoffs even when the offense faltered, but that all crumbled in 1990. Kosar threw more interceptions than touchdowns for the first time in his career, and the defense allowed more points than any other in the league.[237] The Browns' 2–7 start cost Carson his job.[238] Jim Shofner was named as his replacement, at least on an interim basis, and the team finished 3–13.[239] After the season Bill Belichick, the defensive coordinator of the then-Super Bowl champion New York Giants, was named head coach.[240]

Bill Belichick and Modell's move (1991–1995)

Belichick era

Belichick, who came to the Browns after 12 years mostly with the Giants under Bill Parcells, quickly made his mark by restricting media access to the team. He acted gruff or bored at press conferences, shrugging, rolling his eyes and often giving short answers to long questions.[241] This bred the perception that the new coach was not a good communicator and lacked a vision for the team. Behind the scenes, however, he was trying to remake the Browns. He reformed Cleveland's scouting methods and, in conjunction with player personnel director Mike Lombardi, tried to form a coherent identity: a big and strong cold-weather team.[242] Belichick's new way forward, however, did not immediately translate to on-field success. Cleveland's record only improved slightly in 1991 to 6–10 as the offense struggled to produce scoring drives and the defense was plagued by injuries.[243] Kosar was a rare bright spot, passing for almost 3,500 yards and 18 touchdowns.[243] Bridging the end of the 1990 season and the beginning of 1991, the quarterback threw a then-record 307 straight passes without an interception.[244] Kosar broke his ankle twice and sat out for most of the 1992 season, leaving quarterback Mike Tomczak under center. The team finished with a 7–9 record and did not make the playoffs.[243]

By the end of 1992, Kosar's physical decline had long been apparent to Belichick, which left the coach with a difficult choice.[245] Kosar was Cleveland's most popular athlete, a hometown boy who had forgone big money and a bigger profile to lead a struggling team back to the top.[245] While he recognized it would be an unpopular decision, Belichick wanted to bench Kosar, and in 1992 the team picked up a potential replacement in Vinny Testaverde from the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.[246] Belichick named Kosar the starter before the 1993 season,[247] but in the third game against the Raiders, Belichick pulled Kosar after he threw his third interception of the night. Taking over with Los Angeles ahead 13–0, Testaverde led two touchdown drives to win the game. Two weeks later, Belichick named Testaverde the starter. On the verge of tears after a loss to the Dolphins, Kosar said he was disappointed with the decision and felt he had done what he could with what was at his disposal.[248]

Kosar returned after Testaverde suffered a separated right shoulder in a win against the Steelers on October 24, but it was only temporary. The day after a loss against the Broncos the following week, the team cut him.[243] Belichick cited his declining skills, while Modell said it was the right move and asked fans to "bear with us."[249] Fans brought out grills and set fire to their season tickets. A 20-year-old student at Baldwin-Wallace College picketed outside the team's training facilities with a sign that read, "Cut Belichick, Not Bernie."[250] Cleveland won only two of the eight games after Kosar's release, finishing with a 7–9 record for the second year in a row.[243]

Cleveland managed to right the ship in 1994. While the quarterback situation had not stabilized, the defense led the league in fewest points allowed.[251] The Browns finished 11–5, making the playoffs for the first time in four years. The Browns beat the Patriots in a wild-card game,[252] but arch-rival Pittsburgh won a 29–9 victory in the divisional playoff, ending the Browns' season.[253]

Modell's Move

As the Browns recaptured a hint of past glories in 1994, all was not well behind the scenes. Modell was in financial trouble. The origins of Modell's woes dated to 1973, when he worked out a deal to lease Cleveland Municipal Stadium from the city for a pittance: only enough to service the facility's debt and pay property taxes.[254] Cleveland Browns Stadium Corporation, or Stadium Corp., a company Modell and a business associate created and owned, held the 25-year lease. Stadium Corp. then subleased the stadium to the Browns and the Cleveland Indians, and rented it out for concerts and other events.[255] While the deal worked fine for the city and Modell early on, the owner was later dogged by excessive borrowing and lawsuits.[256]

When the stadium was profitable, Modell had used Stadium Corp. to buy land in Strongsville that he had previously acquired as the potential site for a future new stadium. Modell originally paid $625,000 for the land, but sold it to his own Stadium Corp. for more than $3 million. Then, when the stadium was taking losses in 1981, he sold Stadium Corp. itself to the Browns for $6 million. This led to a fight the following year with Bob Gries, whose family had been part of the Browns' ownership group since its founding and had 43% of the team to Modell's 53%. Gries's complaint was that Modell treated the Browns and Stadium Corp. as his own fiefdom, rarely consulting him about the team's business. The sale of Stadium Corp. to the Browns, he argued, enriched Modell at the team's expense.[257] Gries's case went to the Ohio Supreme Court, where he won. In 1986, Modell had to reverse the Browns' purchase of Stadium Corp. and pay $1 million in Gries's legal fees. This left Modell in need of financial help, and it came in the form of Al Lerner, a cigar-chomping banking and real estate executive who bought half of Stadium Corp. and 5% of the Browns in 1986.[258]

His reputation damaged by the lawsuits, Modell was eager to get out of Cleveland. He met with Baltimore officials about selling the Browns to Lerner and buying an expansion team to replace the Colts, who had left for Indianapolis in 1984. He also discussed moving the Browns.[259] Proposals were made to spend $175 million on a stadium renovation after the Indians and Cleveland Cavaliers got new facilities in downtown Cleveland, but it was not enough.[260] As the Browns started the 1995 season with a 4–4 record, word leaked that Modell was moving the team.[261] Beset by rising player salaries and political indifference to the team's financial plight, he said he was forced to move.[262] The day after Modell formally announced the move, Cleveland voters overwhelmingly approved the $175 million of stadium renovations. Modell ruled out a reversal of his decision, saying his relationship with Cleveland had been irrevocably severed. "The bridge is down, burned, disappeared," he said. "There's not even a canoe there for me."[263]

The city immediately sued to prevent the move, on the basis that the lease of the stadium was active until 1998. Fans were in an uproar, staging protests, signing petitions, filing lawsuits and appealing to other NFL owners to block the relocation. Advertisers pulled out of the stadium, fearing fans' ire.[264] Talks between the city, Modell and the NFL continued as the Browns finished the season with a 5–11 record. At the team's final home game against the Bengals, unruly fans in the Dawg Pound bleachers section rained debris, beer bottles and entire sections of seats onto the field, forcing officials to move play to the opposite end to ensure players' safety.[265] Cleveland won the game, its only victory after the announcement of the move.[266]

The following February, the warring parties reached a compromise. Under its terms, Modell was allowed to move the team to Baltimore. In exchange, the league promised Cleveland a reactivated Browns franchise to start play no later than 1999.[267] The $175 million earmarked for stadium improvements was to be used instead build a new stadium, with up to $48 million of additional financial assistance from the NFL. Further, Modell was ordered to pay Cleveland $9.3 million to compensate for lost revenues and taxes during the Browns' three years of inactivity, plus up to $2.25 million of the city's legal fees. Cleveland kept the Browns' colors, logos and history, while Modell's team was technically an expansion franchise, called the Baltimore Ravens.[268]

Inactivity (1996–1998)

Preparations for a reactivated franchise began shortly after Modell, the city and the NFL struck their compromise. The NFL established the Cleveland Browns Trust to direct the Browns' return in early 1996, and in June appointed Bill Futterer as its president. Futterer, who had helped bring NFL and NBA expansion teams to North Carolina, was charged with marketing the team, selling season tickets and representing the NFL's interests in the construction of a new stadium.[269] The trust also leased suites, sold personal seat licenses in the new stadium and reorganized Browns Backers fan clubs.[270] By September 1996, architects were finalizing the design of a new stadium to be built following the destruction of Cleveland Municipal Stadium.[271] Demolition work began on the old stadium in November, and the ground-breaking for the new stadium took place the following May.[272]

As the stadium's construction got underway, the NFL began to search for an owner for the team, which the league decided would be an expansion franchise.[273] A litany of potential owners lined up, including Kosar and a group backed partly by HBO founder Charles Dolan, comedian Bill Cosby and former Miami coach Don Shula.[274][275] The ultimate winner was Al Lerner, the Baltimore man who had helped Modell in 1986 by buying a small stake in the Browns.[276][277] A seven-member NFL expansion committee awarded the team to Lerner for $530 million in September 1998.[277] Lerner, then 65 years old, had a majority share, while Carmen Policy, who helped build the 49ers dynasty of the 1980s, owned 10% of the team and was to run football operations.[277]

As the Browns geared up to reactivate, the Browns Trust set up a countdown clock for the team's return[273] and used Hall of Famers such as Lou Groza and Jim Brown extensively to promote the team, alongside celebrity fans including Drew Carey.[278] Lerner and Policy hired Dwight Clark, a former 49ers wide receiver, as the team's operations director in December 1998.[279] The owners then signed Jacksonville Jaguars offensive coordinator Chris Palmer in January 1999 as the reactivated team's first head coach.[280] The NFL then conducted an expansion draft the following month to stock the new Browns team with players.[281] The team added to its roster through free agency,[282] and was also given the first pick in the draft in April 1999. The Browns used it on quarterback Tim Couch, and took receiver Kevin Johnson and linebacker Rahim Abdullah in the second round.[283]

Construction on the new stadium finished on time in August 1999, paving the way for Cleveland to host a football game for the first time in more than three years.[284] During the years after Modell's move and the Browns' suspension, a dozen new stadiums were built for NFL teams. Citing the precedent set by the Browns' relocation, NFL owners used the threat of a move to convince their cities to build new stadiums with public funds.[285]

Rejoining the NFL (1999–2004)

Cleveland fans' hopes were high upon the arrival of the new team. Having made poor choices in both the expansion draft and the regular NFL draft, however, the Browns floundered. The Steelers shut out the Browns 43–0 in the season opener at Cleveland Browns Stadium on September 12, 1999, the first of seven straight losses. A 2–14 season in 1999 was followed by a 3–13 record in 2000 after Couch suffered a season-ending thumb injury. Early in 2001, Policy and Lerner fired Palmer. The coach and the team, Policy said, were not headed in the right direction.[286]

Mike McCarthy, New Orleans' offensive coordinator, Herman Edwards, a Tampa Bay assistant coach, and Marvin Lewis, Baltimore's defensive coordinator, were mentioned as possible replacements for Palmer.[286] Policy also met with Butch Davis, the head coach of the University of Miami's football team. After rejecting an initial offer in December, Davis accepted the job the following month. Davis had turned around Miami's football program and put the team back in championship contention; Policy and Lerner hoped he could work the same magic in Cleveland.[287]

Butch Davis era

The Browns improved under Davis, and contended for a spot in the 2001 playoffs until a loss in the 15th week against Jacksonville that featured one of the most controversial calls in team history.[288] As time expired in the fourth quarter with the Jaguars ahead 15–10, Couch led a drive into Jacksonville territory. On a fourth-down play that the team needed to convert to stay in the game, Couch threw to receiver Quincy Morgan over the middle. Morgan appeared to bobble the ball before grasping it firmly as he hit the ground. After the pass was ruled complete and Couch spiked the ball to stop the clock, officials reversed Morgan's catch on a Jacksonville challenge. As Davis pleaded his case that the play could not be reviewed because another play had been run, frustrated fans began throwing plastic beer bottles onto the field. Amid the bedlam, later named "bottlegate," officials ended the game with 48 seconds on the clock and left the field as objects rained down on them from the stands.[288] After most of the fans had left, NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue called and ordered the game to be completed. Jacksonville ran down the clock for the win, and the Browns finished the season at 7–9.[289]

Cleveland improved again in 2002, but Lerner did not live to see his team make the playoffs. He died in October 2002 at 69 of brain cancer. Browns players wore a patch with the initials "AL" for the remainder of the season.[290] Ownership of the team, meanwhile, passed to his son Randy.[291] Cleveland finished the season with a 9–7 record, earning a spot in the playoffs as a wild-card team.[292] Couch suffered a broken leg in the final game of the season, however, and backup Kelly Holcomb started in the Browns' first playoff game versus the Steelers. Cleveland held the lead for most of the game as Holcomb passed for 429 yards. But a defensive collapse helped Pittsburgh come charging back in the fourth quarter and win 36–33 to end the Browns' season.[293]

The team's progress under Davis screeched to a halt in 2003. The Browns finished 5–11, and Randy Lerner embarked upon a major front-office reshuffling.[294] Policy resigned unexpectedly as president and chief executive of the Browns in April 2004, saying things had changed after Al Lerner's death. "I opened the door and it was like someone sucked the air and the life out of Berea," he said. "He was a major presence for the organization. I'm talking about the aura, and the inner power of the man."[295] John Collins was named as his replacement.[295] Several other front-office executives also stepped down, including chief contract negotiator Lal Heneghan and lead spokesman Todd Stewart.[296]

The 2004 season was little better, and Davis resigned in November with the team at 3–8. Lerner had given him a contract extension through 2007 that January, but Davis said "intense pressure and scrutiny" made the move necessary.[297] Offensive coordinator Terry Robiskie was named head coach for the remainder of the season, which the Browns finished 4–12.[297]

Struggles and change (2005–present)

Romeo Crennel years

On January 6, 2005, while the Browns were still searching for a new head coach, the team announced Phil Savage's appointment as general manager.[298] Savage, who was director of player personnel for the Baltimore Ravens for two years, had a hand in drafting Ed Reed, Jamal Lewis, Ray Lewis and other stars for the Ravens.[298]

A month later, Cleveland brought in Romeo Crennel as the head coach, signing him to a five-year deal worth $11 million. Crennel was the defensive coordinator for the New England Patriots, who had just won the Super Bowl.[299] His style was described as "quiet, reserved and gentlemanly," but he said he wanted to stock the team with tough, physical players.[299] Before the start of training camp, the Browns acquired veteran quarterback Trent Dilfer from the Seattle Seahawks.[300] In the draft that year the Browns took wide receiver Braylon Edwards with the third pick in the first round.[301]

Dilfer was the starting quarterback to begin the 2005 season. The team started 2–2, but had two three-game losing streaks later in the season and finished with a 6–10 record.[302] In the team's final five games, rookie Charlie Frye took over as the starting quarterback, winning two of those contests. Before the Browns' final regular-season game, the front office was embroiled in a controversy that threatened to send the team into rebuilding mode. Citing sources, ESPN reported that president John Collins was going to fire general manager Phil Savage over "philosophical differences" in managing the salary cap.[303] The resulting uproar from fans and local media was so strong that it was Collins who resigned on January 3, 2006.[304] A replacement for Collins was not immediately named, and Randy Lerner assumed his responsibilities.[304]

Cleveland regressed in the ensuing season, finishing with a 4–12 record. Edwards and tight end Kellen Winslow Jr., who the Browns had drafted in 2004, put up respectable numbers, but the Browns were close to the bottom of the league in points scored and offensive yards gained.[305] Frye injured his wrist toward the end of the season and shared starts with quarterback Derek Anderson, who showed promise in the five games he played in.[306]

60th Moments was a program that was created in 2006 to commemorate the establishment of the team sixty years prior in 1946. The program recaptured the sixty greatest moments in the team's history over the course of the 2006 season. Beginning on September 6, 2006,[307] the Browns' official Web site ran articles that dealt with those sixty moments, and ran the final article on December 31, 2006.[308] Due to their three-year hiatus, the Browns' actual 60th season would be delayed until 2008.

After two losing seasons, the Browns made it back to contention in 2007. After opening with a 34–7 loss to the Steelers, the Browns traded Frye to the Seahawks and put Anderson in as the starter.[309] In his first start, Anderson led the Browns to a surprise 51–45 win over the Cincinnati Bengals, throwing five touchdown passes and tying the franchise record. More success followed, and the Browns finished the regular season with a 10–6 record, the team's best mark since finishing 11–5 in 1994.[310] While the Browns tied with the Steelers for first place in the AFC North, the team missed the playoffs because of two tie-breaking losses to Pittsburgh earlier in the season. Still, six players were selected for the Pro Bowl, including Anderson, Winslow, Edwards, kick returner Josh Cribbs and rookie left tackle Joe Thomas.[311] Crennel agreed to a two-year contract extension until 2011,[312] and the team hired Mike Keenan as team president, filling a position left vacant upon the departure of Collins two years before.[313]

Expectations were high for the 2008 season, but Cleveland finished last in the AFC North with a 4–12 record.[314] Anderson shared starts with Ken Dorsey, who the Browns had acquired by trading away Trent Dilfer, and Brady Quinn, a young quarterback the team drafted in 2007.[315][316] The Browns never contended during 2008 and failed to score a touchdown in the final six games. Near the end of the season, two scandals shook the team. It was revealed that several Browns players, including Winslow, were suffering from staph infections, which raised questions about sanitation in the Browns' Berea practice facilities.[317] In November, Savage found himself in the center of a media storm after an angry e-mail exchange with a fan was published on Deadspin, a sports blog.[318] Shortly after the final game, a 31–0 loss to the Steelers, Lerner fired Savage and, a day later, Crennel.[319]

Eric Mangini and the Holmgren-Heckert era

Cleveland pursued former Steelers coach and Browns linebacker Bill Cowher and former Browns scout Scott Pioli for the head coaching job.[319] The team, however, hired former New York Jets coach Eric Mangini in January 2009.[320] Before the start of the season, Mangini and the front office traded Winslow to the Buccaneers after five seasons marked by injuries and a motorcycle crash that threatened to end the tight end's career.[321] The Browns showed little sign of improvement in Mangini's first year, finishing 5–11 in 2009. While Cleveland lost 11 of its first 12 games, the team won the final four games of the season, including a 13–6 victory over the rival Steelers.[322]

At the end of the season, Lerner hired former Packers coach Mike Holmgren as team president, moving Keenan to chief financial officer.[323] A month later, the owner hired Eagles front-office executive Tom Heckert as general manager.[324] Heckert replaced former general manager George Kokinis, who was fired the previous November. The new management said Mangini would return for a second season.[324]

Under Holmgren and Heckert's watch, the Browns overhauled the quarterbacking corps. Brady Quinn was traded to the Denver Broncos for running back Peyton Hillis in March,[325] while Derek Anderson was released.[326] Meanwhile, Jake Delhomme was acquired from Carolina and Seneca Wallace from Seattle.[327] The team also drafted quarterback Colt McCoy from the University of Texas.[328] With Delhomme as the starting quarterback, Cleveland lost its first three games and continued to struggle. Wallace started four games, but was replaced by McCoy in the second half of the season. Hillis had a breakout season, rushing for 1,177 yards, and was later chosen to appear on the cover of the Madden NFL 12 video game.[329] Despite the emergence of Hillis, the Browns finished with a 5–11 record for the second season in a row, and Mangini was fired in January 2011.[330]

Pat Shurmur takes over

Following Mangini's firing, the Browns named Pat Shurmur as his replacement. Formerly the offensive coordinator for the St. Louis Rams, Shurmur helped groom quarterback Sam Bradford. Holmgren and Heckert hoped he could do the same with McCoy.[331] Contract negotiations between the NFL Players Association and the league shortened the 2011 off-season, which gave Shurmur little time to coach McCoy or institute his version of the West Coast offense.[332] The team started at 2–2, but McCoy's struggles and a lack of offensive production led to a series of defeats, including six straight losses to end the year. The Browns finished the season at 4–12.[333]

In the offseason, Hillis signed as a free agent with the Kansas City Chiefs after a lackluster season and unsuccessful contract talks with the Browns.[334] In the 2012 draft, the Browns chose running back Trent Richardson with the third selection and took quarterback Brandon Weeden with the 22nd pick. Weeden is expected to replace McCoy at quarterback after McCoy's limited success in one and a half seasons as the starter.[335]

On September 6, Art Modell died in Baltimore at the age of 87. Although the Browns planned to have a moment of silence on their home opener for their former owner, his family asked the team not to, well aware of the less-than-friendly reaction it was likely to get.

With Brandon Weeden taking the field, the Browns appeared to be headed for yet another dismal season. The 28-year old rookie QB threw four interceptions in a 17-16 loss to Philadelphia, in which the Browns' only touchdown was scored by the defense.

See also

References

- ^ Cantor 2008, p. v.

- ^ a b Cantor 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Piascik 2007, p. 7.

- ^ Piascik 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Piascik 2007, p. 6–8.

- ^ Piascik 2007, p. 5–9.

- ^ a b c d Piascik 2007, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Schwarz 2010, p. 85.

- ^ a b Piascik 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b Piascik 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Henkel 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Cantor 2008, p. 77.

- ^ Cantor 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Piascik 2007, p. 19.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Piascik 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 105–122.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Piascik 2007, pp. 123–150.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 105–186.

- ^ a b Maxymuk 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Maxymuk 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Jones, Harry (December 20, 1948). "Brown Calls His First Unbeaten and Untied Team Since '40 His Best Yet". Cleveland Plain Dealer. p. 23.

[Brown said:] 'How that boy can run I think he's the greatest fullback that ever lived ... Did you ever see a fullback who runs like a halfback in an open field?'

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Piascik 2007, p. 149–150.

- ^ "Franchises". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Piascik 2007, pp. 13–16.