Jews and the slave trade: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

the opening paragraph is so blatantly bias and non neutral it's ridiculous. " In the middle ages Jews participated in the slave trade" this is neutral, non bias, totally factual and descriptive. |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

{{Antisemitism}} |

{{Antisemitism}} |

||

In the middle ages Jews participated in the slave trade,.<ref>Reiss, The Jews in colonial America, p 85</ref> During the 1490s, trade with the [[New World]] began to open up. At the same time, the monarchies of Spain and Portugal [[Alhambra Decree|expelled all of their Jewish subjects]]. As a result, Jews began participating in all sorts of trade on the Atlantic, including the slave trade. |

|||

Several scholarly works were published <ref name="niz">[http://search.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/ftp.py?orgs/american/wiesenthal.center/web/historical-facts]</ref>demonstrating that Jews did not dominate the slave trade in Medieval Europe, Africa, and/or the [[Americas]],<ref name=Finkelman>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0748-0814%282002%2917%3A1%2F2%3C125%3AJSATST%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage Reviewed Work: Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber] by Paul Finkelman. ''Journal of Law and Religion'', Vol. 17, No. 1/2 (2002), pp. 125-128</ref><ref name=refutations>Refutations of charges of Jewish prominence in slave trade: |

Several scholarly works were published <ref name="niz">[http://search.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/ftp.py?orgs/american/wiesenthal.center/web/historical-facts]</ref>demonstrating that Jews did not dominate the slave trade in Medieval Europe, Africa, and/or the [[Americas]],<ref name=Finkelman>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0748-0814%282002%2917%3A1%2F2%3C125%3AJSATST%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage Reviewed Work: Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber] by Paul Finkelman. ''Journal of Law and Religion'', Vol. 17, No. 1/2 (2002), pp. 125-128</ref><ref name=refutations>Refutations of charges of Jewish prominence in slave trade: |

||

Revision as of 21:45, 11 November 2012

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

In the middle ages Jews participated in the slave trade,.[1] During the 1490s, trade with the New World began to open up. At the same time, the monarchies of Spain and Portugal expelled all of their Jewish subjects. As a result, Jews began participating in all sorts of trade on the Atlantic, including the slave trade.

Several scholarly works were published [2]demonstrating that Jews did not dominate the slave trade in Medieval Europe, Africa, and/or the Americas,[3][4] and that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery.[3][4][5][6] They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean, and in no period did they play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades.[7]

Slavery historian Jason H. Silverman described the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United states as "minuscule", and wrote that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the south.[8] Jews accounted for 1.25% of all Southern slave owners, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves.[8]

Middle Ages

In the middle ages Jews were minimally involved in slave trade.[9]

Leaders of Christianity, including Pope Gregory the Great (pope 590-604), objected to Jews owning Christian slaves, due to concerns about conversion to Judaism and the Talmud's requirement to circumcise slaves.[10] The first prohibition of Jews owning Christian slaves was made by Constantine I in the 4th century. The Third Council of Orléans in 538 repeated the prohibition for Gaul. The prohibition was repeated by subsequent councils - Fourth Council of Orléans (541), Paris (633), Fourth Council of Toledo (633), the Synod of Szabolcs (1092) extended the prohibition to Hungary, Ghent (1112), Narbonne (1227), Béziers (1246). It was part of St. Benedict's rule that Christian slaves were not to serve Jews.[11]

Despite the prohibition Jewish participation in slave trading during the Middle Ages existed to some extent. Jews were the chief traders in the segment of Christian slaves at some epochs[12] and played a significant role in the slave trade in some regions.[13] According to other sources, Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance and also became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews. Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery.[14] Jews participated in routes that had been created by Christians or Muslims but rarely created new trading routes.[13]

During the Middle Ages, Jews acted as slave-traders in Slavonia[15] North Africa,[12] Baltic States,[16] Central and Eastern Europe,[13] Spain and Portugal,[12][13] and Mallorca[17] The most significant Jewish involvement in the slave-trade was in Spain and Portugal in the 10th to 15th centuries.[12][13]

Jewish participation in the slave trade was recorded starting in the 5th century, when Pope Gelasius permitted Jews to introduce slaves from Gaul into Italy, on the condition that they were non-Christian.[18] In the 8th century, Charlemagne (king 768-814) explicitly allowed the Jews to act as intermediaries in the slave trade.[19] In the 10th century, Spanish Jews traded in Slavonian slaves, whom the Caliphs of Andalusia purchased to form their bodyguards.[19] In Bohemia, Jews purchased these Slavonian slaves for exportation to Spain and the west of Europe.[19] William the Conqueror brought Jewish slave-dealers with him from Rouen to England in 1066.[20] At Marseilles in the 13th century, there were two Jewish slave-traders, as opposed to seven Christians.[21]

Middle Ages historical records from the 9th century describes two routes by which Jewish slave-dealers carried slaves from West to East and from East to West.[18] According to Abraham ibn Yakub, Byzantine Jewish merchants bought Slavs from Prague to be sold as slaves. Louis The Fair granted charters to Jews visiting his kingdom, permitting them to trade in slaves, provided the latter had not been baptized. Agobard claimed that the Jews did not abide to the agreement and kept Christians as slaves, citing the instance of a Christian refugee from Cordova who declared that his co-religionists were frequently sold, as he had been, to the Moors. Many of the Spanish Jews owed their fortune to the trade in Slavonian slaves brought from Andalusia.[22] Similarly, the Jews of Verdun, about the year 949, purchased slaves in their neighborhood and sold them in Spain.[23]

Latin America and the Caribbean

Jews participated in the European colonization of the Americas, and they owned slaves in Latin America and the Caribbean, most notably in Brazil and Suriname, but also in Barbados and Jamaica.[24][25][26] Especially in Suriname, Jews owned many large plantations.[27] Many of the ethnic Jews in the New World, particularly in Brazil, were New Christians or Conversos, some of which continued to practice Judaism, so the distinction between Jewish and non-Jewish slave owners is a difficult distinction for scholars to make.

Mediterranean slave trade

In the 17th century, Jews were treated more tolerantly by the Muslim states of North Africa than by Christian Britain and Spain, and consequently many lived in or had close business contacts with Barbary. The Jews of Algiers allegedly were frequent purchasers of Christian slaves brought in by the Barbary corsairs.[28] Meanwhile, Jewish brokers in Livorno (Leghorn), Italy were instrumental in arranging the ransom of Christian slaves from Algiers to their home countries and freedom. Although one slave accused Livorno's Jewish brokers of holding the ransom money until the captives died, this allegation is uncorroborated, and other reports indicate Jews as being very active in assisting the release of English Christian captives.[29] In 1637, an exceptionally poor year for ransoming captives, the few slaves freed were ransomed largely by Jewish factors in Algiers working with Henry Draper.[30]

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade transferred African slaves from Africa to colonies in the New World. Much of the slave trade followed a triangular route: slaves were transported from Africa to the Caribbean, sugar from there to North America or Europe, and manufactured goods from there to Africa.

Jewish participation in the Atlantic slave trade arose as the result of a confluence of two historical events: the expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal, and the discovery of the New World.[31]

After Spain and Portugal expelled many of their Jewish residents in the 1490s, many Jews from Spain and Portugal migrated to the Americas and to Holland, among other destinations. They there formed an important "network of trading families" that enabled them to transfer assets and information that contributed to the emerging South Atlantic economy.[32][33] Other Jews remained in Spain and Portugal, pretending to convert to Christianity, living as Conversos or New Christians.

The only places where Jews really came close to dominating a New World plantation system were the Dutch colonies of Curaçao and Suriname. But the Dutch territories were small, and their importance was short-lived. By the time the slave trade and European sugar-growing reached its peak in the 18th century, Jewish participation was dwarfed by the enterprise of British and French planters who did not allow Jews among their number. During the 19th century, Jews owned some cotton plantations in the southern United States but not in any meaningful numbers.[34]

Jewish participation in the Atlantic slave trade increased through the 17th century because Spain and Portugal maintained a dominant role in the Atlantic trade. Jewish participation in the trade peaked in the early 18th century, but started to decline after the Peace of Utrecht in 1713 when England obtained the right to sell slaves in Spanish colonies, and England and France started to compete with Spain and Portugal.[35]

Jews and descendants of Jews converted to Christianity participated in the slave trade on both sides of the Atlantic, in Holland, Spain, and Portugal on the eastern side, and in Brazil, Caribbean, and North America on the west side.[36] However other than a momentary involvement in Brazil and a more durable one in the Caribbean, Jewish participation was minimal.[37]

Brazil

The role of Jewish converts to Christianity (New Christians) and of Jewish traders was momentarily significant in Brazil[38] and the Christian inhabitants of Brazil were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco, and some Jews were among the leading slave traders in the colony.[39] Some Jews from Brazil migrated to Rhode Island in the American colonies, and played a significant but non dominant role in the 18th-century slave trade of that colony, but this sector accounted for only a very tiny portion of the total human exports from Africa.[40]

Caribbean and Suriname

The New World location where the Jews played the largest role in the slave-trade was in the Caribbean and Suriname, most notably in possessions of Holland, that were serviced by the Dutch West India Company.[38] The slave trade was one of the most important occupations of Jews living in Suriname and the Caribbean.[41] The Jews of Suriname were the largest slave-holders in the region.[42]

The only places where Jews came close to dominating the New World plantation systems were Curaçao and Suriname.[43] Slave auctions in the Dutch colonies were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday.[44] Jewish merchants in the Dutch colonies acted as middlemen, buying slaves from the Dutch West India Company, and reselling them to plantation owners.[45] The majority of buyers at slave auctions in the Brazil and the Dutch colonies were Jews.[46]

Jews played a "major role" in the slave trade in Barbados[44][47] and Jamaica.[44]

Jewish plantation owners in Suriname helped to suppress several slave revolts in the period 1690 to 1722.[42]

Curaçao

In Curaçao, Jews were involved in trading slaves, although at a far lesser extent compared to the Protestants of the island.[48] Jews imported fewer than 1,000 slaves to Curaçao between 1686 and 1710. After that time slave trade diminished.[44][49] Between 1630 and 1770, Jewish merchants settled or handled a "considerable portion" of the eighty-five thousand slaves who landed in Curaçao, about one-sixth of the total Dutch slave trade.[50]

North American colonies

The Jewish role in the American slave trade was minimal.[51]

According to Bertram Korn, there were Jewish owners of plantations, but altogether they constituted only a tiny proportion of the industry.[52] In 1830 there were only four Jews among the 11,000 Southerners who owned fifty or more slaves.[53]

Of all shipping ports in Colonial America, Jewish merchants only played a significant part in the slave-trade of American Colonies only in Newport, Rhode Island.[54]

A table of the commissions of brokers in Charleston, SC, shows that one Jewish brokerage accounted for 4% of the commissions. According to Bertram Korn, Jews accounted for 4 of the 44 slave-brokers in Charleston, three of 70 in Richmond, and 1 of 12 in Memphis.[55]

Notable Slave Traders

The most dominant Jewish slave traders on the American continent included Isaac Da Costa of Charleston in the 1750s, David Franks of Philadelphia in the 1760s, and Aaron Lopez of Newport in the late 1760s and early 1770s.[44][56] According to historian Eli Faber, the ventures of Aaron Lopez in the slave trade were "infinitesimal" compared to other British slaving expeditions of the time.[57]

Assessing the extent of Jewish involvement in the Atlantic slave trade

Historian Seymour Drescher emphasized the problems of determining whether or not slave-traders were Jewish. He concludes that New Christian merchants managed to gain control of a sizeable share of all segments of the Portuguese Atlantic slave trade during the Iberian-dominated phase of the Atlantic system. Due to forcible conversions of Jews to Christianity many New Christians continued to practice Judaism in secret, meaning it is impossible for historians to determine what portion of these slave traders were Jewish, because to do so would require the historian to choose one of several definitions of "Jewish".[60][61]

Early assessments

Historian Heinrich Graetz, in History of the Jews (published 1853-1875) was the first historian to document Jewish participation in the slave trade, although he limits his scope to Europe, and does not address the Atlantic slave trade.[62]

In 1960, Arnold Wiznitzer, published Jews in colonial Brazil, in which he wrote that Jews "dominated the slave trade"[63] in Brazil in the mid-17th century. Wiznitzer's statement was subsequently quoted in antisemitic literature, but sometimes taken out of context so it seemed to apply to the entire Atlantic slave trade.[64][65]

In 1983, Marc Lee Raphael, professor of history, wrote Jews and Judaism in the United States: a documentary history which discussed Jews in the Atlantic slave trade and asserted that "Jewish merchants played a major role in the slave trade. In fact, in all the American colonies, whether French (Martinique), British, or Dutch, Jewish merchants frequently dominated. This was no less true on the North American mainland, where during the eighteenth century Jews participated in the 'triangular trade' that brought slaves from Africa to the West Indies and there exchanged them for molasses, which in turn was taken to New England and converted into rum for sale in Africa."[66] Later scholars would challenge Raphael's assessment of the extent of Jewish participation in the slave-trade.[citation needed]

Ralph A. Austen asserts that scholars, prior to 1991, were reluctant to publicize Jewish involvement in slavery because of fear of damaging the "shared liberal agenda" of Jews and Blacks.[67] Austen uses the term "benign myth" to describe the notion that Jews have always fought against slavery of oppressed peoples, and states that scholars, before 1991, supported that myth by avoiding public discussion of evidence that Jews were involved in slavery.[68] Austen points out that Jewish participation in the slave trade calls into question the image of Jews as victims in medieval-to-modern world history.[69][70]

The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews

In 1991, the Nation of Islam published the book The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews, which alleged that Jews dominated the Atlantic slave trade.[71] Volume 1 of the book claims that Jews played a major role in the Atlantic slave trade, and profited from black slavery.[72] The book was heavily criticized for being antisemitic, and for failing to provide an objective analysis of the role of Jews in the slave trade. Common criticisms were that the book used selective quotes, made "crude use of statistics",[32] and was purposefully trying to exaggerate the role of Jews.[73]

The Anti-Defamation League criticized the Nation of Islam and the book.[6] Henry Louis Gates Jr criticized the book's intention and scholarship.[74]

Historian Ralph A. Austen, heavily criticized the book and said that although the book "seems fairly accurate" it is an antisemitic book, whose "distortions are produced almost entirely by selective citation rather than explicit falsehood.... more frequently there are innuendos imbedded in the accounts of Jewish involvement in the slave trade",[75] and "[w]hile we should not ignore the anti-Semitism of The Secret Relationship..., we must recognize the legitimacy of the stated aim of examining fully and directly even the most uncomfortable elements in our [Black and Jewish] common past".[76]

According to Elizabeth Potter, The Secret Relationship ignores facts that show that Jews behaved no differently from a moral point of view than anyone else in their era regarding slave trade.[77]

Later assessments

The publication of The Secret Relationship spurred detailed research into the participation of Jews in the Atlantic slave trade, resulting in the publication of the following works, most of which were published specifically to refute the thesis of The Secret Relationship:

- 1992 - Harold Brackman, Jew on the brain: A public refutation of the Nation of Islam's The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews

- 1992 - David Brion Davis, "Jews in the Slave Trade", in Culturefront (Fall 1 992) pp 42–45.

- 1993 - Seymour Drescher, "The Role of Jews in the Atlantic Slave Trade", Immigrants and Minorities, 12 (1993), pp 113–125.

- 1993 - Marc Caplan, Jew-Hatred As History: An Analysis of the Nation of Islam's "The Secret Relationship" (published by the Anti Defamation League)

- 1998 - Eli Faber, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, New York University Press.

- 1999 - Saul S. Friedman, Jews and the American Slave Trade, Transaction.

Most post-1991 scholars that analysed the role of Jews in the overall Atlantic slave trade concluded that it was "minimal", and only identified certain regions (such as Brazil and the Caribbean) where the participation was "significant".[78]

Wim Klooster wrote: "In no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean. Even when Jews in a handful of places owned slaves in proportions slightly above their representation among a town's families, such cases do not come close to corroborating the assertions of The Secret Relationship."[7]

David Brion Davis wrote that "Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery."[79] Jacob R. Marcus wrote that Jewish participation in the American Colonies was "minimal" and inconsistent.[80] Bertram Korn wrote "all of the Jewish slavetraders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South."[81]

According to a review in The Journal of American History of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber and Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman: "Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors."[82]

According to Seymour Drescher, Jews participated in the Atlantic slave trade, particularly in Brazil and Suriname,[83] however in no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades.[7] He said that Jews rarely established new slave-trading routes, but rather worked in conjunction with a Christian partner, on trade routes that had been established by Christians and endorsed by Christian leaders of nations.[84][85] In 1995 the American Historical Association (AHA) issued a statement, together with Drescher, condemning "any statement alleging that Jews played a disproportionate role in the Atlantic slave trade".[86]

Allegations that Jews had a major contribution to Atlantic slave trade were denied by David Brion Davis, who argued that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery.[5] These charges were widely refuted by other scholars, as well.[3][4][6] While acknowledging Jewish participation in slavery, scholars reject allegations that Jews dominated the slave trade in Medieval Europe, Africa, and/or the Americas.[3][4]

According to a review in The Journal of American History of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber and Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman:

Eli Faber takes a quantitative approach to Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade in Britain's Atlantic empire, starting with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the London resettlement of the 1650s, calculating their participation in the trading companies of the late seventeenth century, and then using a solid range of standard quantitative sources (Naval Office shipping lists, censuses, tax records, and so on) to assess the prominence in slaving and slave owning of merchants and planters identifiable as Jewish in Barbados, Jamaica, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and all other smaller English colonial ports. He follows this strategy in the Caribbean through the 1820s; his North American coverage effectively terminates in 1775. Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors.[87]

Jewish slave ownership in the southern United States

Slavery historian Jason H. Silverman describes the part of Jews in slave trading in the southern United states as "minuscule", and wrote that the historical rise and fall of slavery in the United States would not have been affected at all had there been no Jews living in the south.[8] Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners.[8]

Jewish slave ownership practices in the southern United States were governed by regional practices, rather than Judaic law.[88][89][8] Many southern Jews held the view that blacks were subhuman and were suited to slavery, which was the predominant view held by many of their non-Jewish southern neighbors.[90]

Jews conformed to the prevailing patterns of slave ownership in the South, and were not significantly different from other slave owners in their treatment of slaves.[8] Rich Jews in the south generally preferred employing white servants rather than owning slaves.[89] Jewish slave owners included Aaron Lopez, Francis Salvador, Judah Touro, and Haym Salomon.[91]

Jewish slave owners were found mostly in business or domestic settings, rather than plantations, so most of the slave ownership was in an urban context - running a business or as domestic servants.[88][89]

Jewish slave owners freed their black slaves at about the same rate as non-Jewish slave owners.[8] Jewish slave owners sometimes bequeathed slaves to their children in their wills.[8]

Abolition debate

A significant number of Jews gave their energies to the antislavery movement.[92] Many Jews of the 19th century, such as Adolphe Crémieux, participated in the moral outcry against slavery. In 1849, Crémieux announced the abolition of slavery throughout the French possessions.[93]

In England there were Jewish members of the abolition groups. Granville Sharp and Wilberforce, in his "A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade," employed Jewish teachings as arguments against slavery. Rabbi G. Gottheil of Manchester, and Dr. L. Philippson of Bonn and Magdeburg, forcibly combated the view announced by Southern sympathizers, that Judaism supports slavery. Rabbi M. Mielziner's anti-slavery work "Die Verhältnisse der Sklaverei bei den Alten Hebräern," published in 1859, was translated and published in the United States.[93]

Similarly, in Germany, Berthold Auerbach in his fictional work "Das Landhausam Rhein" aroused public opinion against slavery and the slave trade, and Heinrich Heine also spoke against slavery.[93]

Immigrant Jews were among abolitionist John Brown’s band of antislavery fighters in Kansas: Theodore Wiener, from Poland; Jacob Benjamin, from Bohemia; and August Bondi (1833-1907), from Vienna.[94]

The Jewish woman Ernestine Rose was called “queen of the platforms” in the 19th century because of her speeches in favor of abolition.[95] Her lectures were met with controversy. When she was in the South to speak out against slavery, one slaveholder told her he would have "tarred and feathered her if she had been a man". When, in 1855, she was invited to deliver an anti-slavery lecture in Bangor, Maine, a local newspaper called her "a female Atheist... a thousand times below a prostitute." When Rose responded to the slur in a letter to the competing paper, she sparked off a town feud that created such publicity that, by the time she arrived, everyone in town was eager to hear her. Her most ill-received lecture was likely in Charleston, West Virginia, where her lecture on the evils of slavery was met with such vehement opposition and outrage that she was forced to exercise considerable influence to even get out of the city safely. [96]

In the civil-war era, prominent Jewish religious leaders in the United States engaged in public debates about slavery.[97] Generally, rabbis from the Southern states supported slavery, and those from the North opposed slavery.[98] The most notable debate[99] was between rabbi Morris Jacob Raphall, who defended slavery as it was practiced in the South because slavery was endorsed by the Bible, and rabbi David Einhorn who opposed its current form.[100] However, there were not many Jews in the South, and Jews accounted for only 1.25% of all Southern slave owners.[8] In 1861, Raphall published his views in a treatise called "The Bible View of Slavery".[101] He wrote, "I am no friend to slavery in the abstract, and still less friendly to the practical working of slavery, But I stand here as a teacher in Israel; not to place before you my own feelings and opinions, but to propound to you the word of G-d, the Bible view of slavery."[102] Raphall, and other pro-slavery rabbis such as Isaac Leeser and J. M. Michelbacher (both of Virginia), used the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) to support their argument.[103] Abolitionist rabbis, including Einhorn and Michael Heilprin, concerned that Raphall's position would be seen as the official policy of American Judaism, vigorously refuted his arguments, and argued that slavery – as practiced in the South – was immoral and not endorsed by Judaism.[104]

Nathan Meyer Rothschild was known for his role in the abolition of the slave trade through his part-financing of the £20 million British government buyout of the plantation industry's slaves.[105] In 2009 it was claimed that as part of banking dealings with a slave owner, Rothschild used slaves as collateral. The Rothschild bank denied the claims and said that Nathan Mayer Rothschild had been a prominent civil liberties campaigner with many like-minded associates and “against this background, these allegations appear inconsistent and misrepresent the ethos of the man and his business”.[106]

Modern times

In the modern era, Jews and African-Americans have often cooperated in the Civil Rights movement, motivated partially by the common background of slavery, particularly the story of the Jewish enslavement in Egypt, as told in the Biblical story of the Book of Exodus, which many blacks identified with.[107] Seymour Siegel suggests that the historic struggle against prejudice faced by Jews led to a natural sympathy for any people confronting discrimination. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, stated the following when he spoke from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial during the famous March on Washington on August 28, 1963: "As Jews we bring to this great demonstration, in which thousands of us proudly participate, a twofold experience—one of the spirit and one of our history... From our Jewish historic experience of three and a half thousand years we say: Our ancient history began with slavery and the yearning for freedom. During the Middle Ages my people lived for a thousand years in the ghettos of Europe... It is for these reasons that it is not merely sympathy and compassion for the black people of America that motivates us. It is, above all and beyond all such sympathies and emotions, a sense of complete identification and solidarity born of our own painful historic experience."[108][109]

See also

Notes

- ^ Reiss, The Jews in colonial America, p 85

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d Reviewed Work: Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber by Paul Finkelman. Journal of Law and Religion, Vol. 17, No. 1/2 (2002), pp. 125-128

- ^ a b c d Refutations of charges of Jewish prominence in slave trade:

- "Nor were Jews prominent in the slave trade." - Marvin Perry, Frederick M. Schweitzer: Antisemitism: Myth and Hate from Antiquity to the Present. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0-312-16561-7. p.245

- "In no period did Jews play a leading role as financiers, shipowners, or factors in the transatlantic or Caribbean slave trades. They possessed far fewer slaves than non-Jews in every British territory in North America and the Caribbean. Even when Jews in a handful of places owned slaves in proportions slightly above their representation among a town's families, such cases do not come close to corroborating the assertions of The Secret Relationship." - Wim Klooster (University of Southern Maine): Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight. By Eli Faber. Reappraisals in Jewish Social and Intellectual History. William and Mary Quarterly Review of Books. Volume LVII, Number 1. by Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 2000

- "Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance and also became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews... Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery. ... Whatever Jewish refugees from Brazil may have contributed to the northwestward expansion of sugar and slaves, it is clear that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery." - Professor David Brion Davis of Yale University in Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1984), p.89 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- "The Jews of Newport seem not to have pursued the [slave trading] business consistently ... [When] we compare the number of vessels employed in the traffic by all merchants with the number sent to the African coast by Jewish traders ... we can see that the Jewish participation was minimal. It may be safely assumed that over a period of years American Jewish businessmen were accountable for considerably less than two percent of the slave imports into the West Indies" - Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-703 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- "None of the major slave-traders was Jewish, nor did Jews constitute a large proportion in any particular community. ... probably all of the Jewish slave-traders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South." - Bertram W. Korn, Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865, in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol. 3, pp. 197-198 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- "[There were] Jewish owners of plantations, but altogether they constituted only a tiny proportion of the Southerners whose habits, opinions, and status were to become decisive for the entire section, and eventually for the entire country. ... [Only one Jew] tried his hand as a plantation overseer even if only for a brief time." - Bertram W. Korn, Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865, in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol. 3, p. 180. (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- ^ a b Davis, David Brion (1984), Slavery and Human Progress, New York: Oxford Univ. Press, p. 89

- ^ a b c Anti-Semitism. Farrakhan In His Own Words. On Jewish Involvement in the Slave Trade and Nation of Islam. Jew-Hatred as History. ADL December 31, 2001

- ^ a b c Wim Klooster (University of Southern Maine): Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight. By Eli Faber. Reappraisals in Jewish Social and Intellectual History. William and Mary Quarterly Review of Books. Volume LVII, Number 1. by Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rodriguez, p 385

- ^ Reiss, The Jews in colonial America, p 85

- ^ Abrahams, pp 97, 99

- ^ Aronius, "Regesten", No. 114

- ^ a b c d Hastings, p 620

- ^ a b c d e Drescher, p 107

- ^ David Brion Davis of Yale University, Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1984), p.89 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- ^ Graetz, Heinrich, History of the Jews, vol iii, p 305 (Engl. translation by P. Bloch)

- ^ Dreshcer, p 111

- ^ Schorsch, p 52

- ^ a b Slave Trade. Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c Abrahams, p 98

- ^ Abrahams, p 99

- ^ "R. E. J." xvi.

- ^ Heinrich Graetz, "History of the Jews", vii.

- ^ Aronius, "Regesten", No. 127

- ^ "Suriname",The Historical encyclopaedia of world slavery, Volume 1 By Junius P. Rodriguez, p 622

- ^ Reiss, p 86

- ^ Schorsch, p 60

- ^ Rodriguez, p 622

- ^ Hebb, p. 153.

- ^ Hebb, p. 160

- ^ Hebb, p. 163, n. 5

- ^ Schorsch:* page 50: "Jewish slave owning [in medieval times] remained minimal. Only with the confluence of the relative Protestant religious tolerance and the socioeconomic needs generated by overseas colonization did Jews emerge as players of note in the slave economy of western Protestant nations".

- ^ a b Austen, p 134

- ^ Drescher-EAJH -vol1 2)" [minimal involvement in the slave-trade] does not hold for the New Christian descendants of Jews during the period of Iberian domination (1450-1640). Their importance in the development of the slave trade to the Americas must be given its due. When Portuguese merchants became the first global trading diaspora, New Christians were prominent in its growth…. As a loose network of trading families, they pioneered in the formation of the European-Asian-African-American complex that contributed to the New World's first African based slave economies." page 416

- ^ Austen: p 134

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST: - p 451: "J mercantile influence in the politics of the Atlantic slave trade probably reached its peak in the opening years of the eighteenth century....the political and the economic prospects of Dutch Sephardic [Jewish] capitalists rapidly faded, however, when the English emerged with the asiento [permission to sell slaves in Spanish possessions] at the Peace of Utrecht in 1713".

- ^ Drescher, p 107: "A small fragment of the Jewish diaspora fled ... westward into the Americas, there becoming entwined with the African slave trade"....they could only prosper by moving into high risk and new areas of economic development. In the expanding Western European economy after the Columbus voyages, this meant getting footholds within the new markets at the fringes of Europe, primarily in overseas enclaves. One of these new 'products' was human beings. It was here that Jews, or descendants of Jews, appeared on the rosters of Europe's slave trade".

- ^ Drescher JANCAST: p 455: "only in the Americas - momentarily in Brazil, more durably in the Caribbean - can the role of Jewish traders be described as significant." .. but elsewhere involvement was modest or minimal p 455.

- ^ a b Drescher: JANCAST: p 455: "only in the Americas - momentarily in Brazil, more durably in the Caribbean - can the role of Jewish traders be described as significant." p 455.

- ^ Herbert I. Bloom "The Christian inhabitants [of Brazil] were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco and were among the leading slave-holders and slave traders in the colony." page 133 of The Economic activities of the Jews in Amsterdam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries" by Herbert Ivan Bloom

- ^ Austen* p 135: "Jews of Portuguese Brazilian origin did play a significant (but by no means dominant) role in the eighteenth-century slave trade of Rhode Island, but this sector accounted for only a very tiny portion of the total human exports from Africa."

- ^ "Slave trade [sic] was one of the most important Jewish activities here [in Surinam] as elsewhere in the colonies." page 159 same book 2. The Economic Activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Port Washington, New York/London: Kennikat Press, 1937), p. 159.

- ^ a b Roth, p 292

- ^ Austen* p 135: "the only places where Jews really came close to dominating the New World plantation system were the Dutch colonies of Curaçao and Surinam.... but the Dutch territories were small, and their importance shortlived."

- ^ a b c d e Raphael, p 14

- ^ Kritzler, p 135: "While the [Dutch West India] Company held a monopoly on the slave trade, and made a 240 percent profit per slave, Jewish merchants, as middlemen, also had a lucrative share, buying slaves at the Company auction and selling them to planters on an installment plan - no money down, three years to pay at an interest rate of 40-50 percent. ... With their large profits - slaves were marked up by 300 percent ... - they built stately homes in Recife, and owned ten of the 166 sugar plantations, including "some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco" ". [ he is quoting Herbert Bloom in that last sentence]

- ^ Wiznitzer, Arnold, Jews in Colonial Brazil, Columbia Univ Press, 1960, p 70. Quoted by Schorsch, p 59: The West India Company, which monopolized imports of slaves from Africa, sold slaves at public auctions against cash payment. "It happened that cash was mostly in the hands of Jews. The buyers who appeared at the auctions were almost always Jews, and because of this lack of competitors they could buy slaves at low prices. On the other hand, there also was no competition in the selling of the slaves to the plantation owners and other buyers, and most of them purchased on credit payable at the next harvest in sugar. Profits up to 300 percent of the purchase value were often realized with high interest rates"

- ^ Schorsh, 60

- ^ Jews and blacks in the early modern world, Jonathan Schorsch, p. 61

- ^ Schorsch p 62: In Curaçao: "Jews also participated in the local and regional trading of slaves"

- ^ Drescher, JANCAST, p 450

- ^ Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-703

- ^ Bertram W. Korn, "Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865," in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, MA: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol. 3, p. 180:

- ^ Historical Facts vs. Antisemitic Fictions: The Truth About Jews, Blacks, Slavery, Racism and Civil Rights / Prepared under the auspices of the Simon Wiesenthal Center by Dr. Harold Brackman and Professor Mary R. Lefkowitz. 1993

- ^ Drescher, EAJH-vol1 - page 415: Newport, RI, USA: "Newport [Rhode Island] was the leading African slaving port during the eighteenth century and the only port in which Jewish merchants played a significant part. At the peak period of their participation in slaving expeditions (the generation before the Am. Revolution), Newport's Jewish merchants handled up to 10 percent of the Rhode Island slave trade. Incomplete records for other eighteenth-century ports in which Jews participated in the slave trade in any way show that for a few years they held at least partial shares in up to 8 percent of New York's small number of slaving voyages, usually from African to Caribbean ports.

- ^ Drescher, EAJH-vol1 - page 415: internal traffic within US (Korn 1973).

- ^ Reiss, Oscar, The Jews in colonial America, McFarland, 2004 pp 86-87

- ^ Jews, slaves, and the slave trade: setting the record straight, Eli Faber, NYU Press, 1998, pp. 143

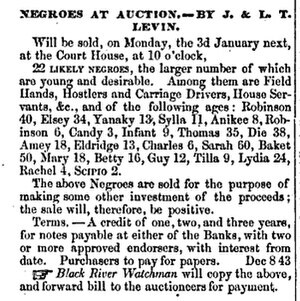

- ^ Ad from A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Together with corroborative statements verifying the truth of the work by Harriet Beecher Stowe, published by T. Bosworth, 1853

- ^ Information on Jacob Levin found at Jews and the American Slave Trade, by Saul S. Friedman, p 157

- ^ Drescher, p 109

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST: page 447: "New Christian merchants managed to gain control of a sizeable, perhaps major, share of all segments of the Portuguese Atlantic slave trade during the Iberian-dominated phase of the Atlantic system. I have come across no description of the Portuguese slave trade that estimates the relative shares of the various participants in the slave trade by the racial-religious designation, but New Christian families certainly oversaw the movement of a vast number of slaves from Africa to Brazil during its first-century period [1600-1700]."

- ^ "History of the Jews, translated by Philipp Bloch. vol. iii, ch 2, p. 28-29, 34, 40, 142, 229, 305; vol. iv; ch 3; vol. vii),

- ^ Wiznitzer, Arnold, Jews in colonial Brazil, Columbia University Press, 1960, p 72

- ^ In the image of God: religion, moral values, and our heritage of slavery By David Brion Davis, p 67. Davis shows how Wiznitzer also wrote that "Jews did not play a dominant role as [sugar plantation owners]" uses this as an example of how antisemitic polemics use selective quotes to present a biased view of history.

- ^ Schorsch, p 59

- ^ Raphael, Jews and Judaism in the United States: a documentary history, p. 14

- ^ Austen, p 131-135

- ^ Austen, p 131: "John Hope Franklin and I [Ralph A. Austen] were both aware that Sephardic Jews in the New World had been heavily involved in the African slave trade.... Franklin and I, [ by not speaking up and acknowledging that jews were involved in the slave trade] in effect, were condoning a benign historical myth: that the shared liberal agenda of twentieth-century Blacks and Jews has a pedigree going back through the entire remembered past.... We, the Jews, had also experienced history on the side of the enslaved and always cried out in anguish against the oppression of the enslavers.... Jewish students of Jewish history have known it was untrue and, over several decades, have produced a significant body of scholarship detailing the involvement of our ancestors in the Atlantic slave trade and Pan-American slavery. Until recently, this work remained buried in scholarly journals, read only by other specialists. It had never been synthesized in a publication for non-scholarly audience. A book of this sort has now appeared, however, written not by Jews but by an anonymous group of African Americans associated with the Reverend Louis Farrakhan's Nation of Islam."

- ^ Austen p 135: "The fact that our [Jewish] forefathers were generally, and at times quite significantly, on the side of the slavers in the cruel world of the Atlantic economy may also help call into question of the whole image of Diaspora Jews as 'victims' in medieval-to-modern world history." (p 135).

- ^ See also Hezser, Catherine, 2005, Jewish slavery in antiquity, Oxford University Press, pp 3-5, which discusses how some scholars over-emphasized the humaneness of Jewish slave ownership practices.

- ^ Austen, pp 131-133

- ^ Foxman, Abraham. Jews and Money. pp. 130–135.

- ^ Austen p 133-134

- ^ "Black Demagogues and Pseuo-Scholars", New York Times, 20 July 1002, p. A15.

- ^ Austen, p 133

- ^ Austen, p 136

- ^ Feminism and philosophy of science, Elizabeth Potter, Routledge, 2006, pp. 78

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST: p 455: "only in the Americas - momentarily in Brazil, more durably in the Caribbean - can the role of Jewish traders be described as significant." .. but elsewhere involvemnent was modest or minimal p 455.

- ^ "Medieval Christians greatly exaggerated the supposed Jewish control over trade and finance and also became obsessed with alleged Jewish plots to enslave, convert, or sell non-Jews... Most European Jews lived in poor communities on the margins of Christian society; they continued to suffer most of the legal disabilities associated with slavery. ... Whatever Jewish refugees from Brazil may have contributed to the northwestward expansion of sugar and slaves, it is clear that Jews had no major or continuing impact on the history of New World slavery." - Professor David Brion Davis of Yale University in Slavery and Human Progress (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1984), p.89 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- ^ "The Jews of Newport seem not to have pursued the [slave trading] business consistently ... [When] we compare the number of vessels employed in the traffic by all merchants with the number sent to the African coast by Jewish traders ... we can see that the Jewish participation was minimal. It may be safely assumed that over a period of years American Jewish businessmen were accountable for considerably less than two percent of the slave imports into the West Indies" - Professor Jacob R. Marcus of Hebrew Union College in The Colonial American Jew (Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press, 1970), Vol. 2, pp. 702-703 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- ^ "None of the major slavetraders was Jewish, nor did Jews constitute a large proportion in any particular community. ... probably all of the Jewish slavetraders in all of the Southern cities and towns combined did not buy and sell as many slaves as did the firm of Franklin and Armfield, the largest Negro traders in the South." - Bertram W. Korn, Jews and Negro Slavery in the Old South, 1789-1865, in The Jewish Experience in America, ed. Abraham J. Karp (Waltham, Massachusetts: American Jewish Historical Society, 1969), Vol. 3, pp. 197-198 (cited in Shofar FTP Archive File: orgs/american/wiesenthal.center//web/historical-facts)

- ^ "Eli Faber takes a quantitative approach to Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade in Britain's Atlantic empire, starting with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in the London resettlement of the 1650s, calculating their participation in the trading companies of the late seventeenth century, and then using a solid range of standard quantitative sources (Naval Office shipping lists, censuses, tax records, and so on) to assess the prominence in slaving and slave owning of merchants and planters identifiable as Jewish in Barbados, Jamaica, New York, Newport, Philadelphia, Charleston, and all other smaller English colonial ports. He follows this strategy in the Caribbean through the 1820s; his North American coverage effectively terminates in 1775. Faber acknowledges the few merchants of Jewish background locally prominent in slaving during the second half of the eighteenth century but otherwise confirms the small-to-minuscule size of colonial Jewish communities of any sort and shows them engaged in slaving and slave holding only to degrees indistinguishable from those of their English competitors." from Book Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber and Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman The Journal of American History Vol 86. No. 3 December 1999

- ^ Drescher: JANCAST: p 455:

- ^ Drescher, EAJH-vol1 "The available evidence indicates that the Jewish network probably counted for little in Atlantic slaving. The few cases of long-term Jewish participation in the eighteenth-centurey slave trades offer evidence of cross-religious networks as keys to their success. In case after case, Jews who participated in multiple slaving voyages ... linked themselves to Christian agents or partners. It was not as Jews, but as merchants, that traders ventured into one of the great enterprises of the early modern world." Drescher, in Ency Am. J. Hist. p. 416.

- ^ Drescher, p 107-108

- ^ Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1, pp. 199

- ^ Book Review of Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight by Eli Faber and Jews and the American Slave Trade by Saul S. Friedman The Journal of American History Vol 86. No. 3 December 1999

- ^ a b Greenberg, p 110

- ^ a b c Reiss, p 88

- ^ Reiss, p 84

- ^ Friedman, Saul S., Jews and the American Slave Trade;; pp xiii, 123-127.

- ^ Maxwell Whiteman, "Jews in the Antislavery Movement," Introduction to The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: The Narrative of Peter and Vina Still (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1970), pp. 28, 42

- ^ a b c ANTISLAVERY MOVEMENT AND THE JEWS, Max J. Kohler

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [hhttp://books.google.com/books?id=Vn4uAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA271l]

- ^

- Kenvin, Helene Schwartz (1986). This Land of Liberty: A History of America's Jews. Behrman House, Inc. pp. 90–92. ISBN 0-87441-421-0.

- Benjamin, Judah P. "Slavery and the Civil War: Part II" in United States Jewry, 1776-1985: The Germanic Period, Jacob Rader Marcus (Ed.), Wayne State University Press, 1993, pp. 13-34.

- ^ Hertzberg, Arthur (1998). The Jews in America: four centuries of an uneasy encounter : a history. Columbia University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 0-231-10841-9.

- ^

- Benjamin, Judah P. "Slavery and the Civil War: Part II" in United States Jewry, 1776-1985: The Germanic Period, Jacob Rader Marcus (Ed.), Wayne State University Press, 1993, pp. 17-19.

- Adams, Maurianne (1999). Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. 190–194. ISBN 1-55849-236-4.

- ^ Friedman, Murray (2007). What went wrong?: the creation and collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance. Simon and Schuster. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Sherman, Moshe D. (1996). Orthodox Judaism in America: a biographical dictionary and sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170. ISBN 0-313-24316-6.

- ^ The Bible View of Slavery, By: Rabbi Dr. M.J. Raphall Congregation B'nai Jeshurun, New York City 1861

- ^

- Friedman, Murray (2007). What went wrong?: the creation and collapse of the Black-Jewish Alliance. Simon and Schuster. p. 25.

- Sherman, Moshe D. (1996). Orthodox Judaism in America: a biographical dictionary and sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170. ISBN 0-313-24316-6.

- ^ Adams, Maurianne (1999). Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. 190–194. ISBN 1-55849-236-4.. Adams writes that Raphall's position was "accepted by many as the Jewish position on the slavery question.... Raphall was a prominent Orthodox rabbi and so the sermon was used in the South to prove the Biblical sanction of slavery and the American Jews' sympathy with the secession movement."

- ^ "Hochschild, Adam "Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire's Slaves" Houghton Mifflin: New York, NY (2005). p. 347". Worldcat.org. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- ^ [4]

- ^ Kaufman, pp 3, 268

- ^ Joachim Prinz March on Washington Speech

- ^ Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement - March on Washington

References

- Abrahams, Israel, Jewish life in the middle ages, The Macmillan Co., 1919

- Austen, Ralph A., "The Uncomfortable Relationship: African Enslavement in the Common History of Blacks and Jews", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States, Maurianne Adams (Ed.), Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1999, pp 131–135.

- Bloom, Herbert I., A study of Brazilian Jewish history 1623-1654: based chiefly upon the findings of the late Samuel Oppenheim, 1934.

- Brackman, Harold, Jew on the brain: A public refutation of the Nation of Islam's The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews (self-published), 1992. Later re-named and re-published as Farrakhan's Reign of Historical Error: The Truth behind The Secret Relationship (published by the Simon Wiesenthal Center). Expanded into a book in 1994: Ministry of Lies: The Truth Behind the Nation of Islam's "the Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews" (published by Four Walls, Eight Windows).

- Caplan, Marc Jew-Hatred As History: An Analysis of the Nation of Islam's "The Secret Relationship" (published by the Anti Defamation League), 1993.

- Davis, David Brion, "Jews in the Slave Trade", in Culturefront (Fall 1 992) pp 42–45.

- Drescher, Seymour, "The Role of Jews in the Transatlantic Slave Trade", in Strangers & neighbors: relations between Blacks & Jews in the United States, Maurianne Adams (Ed.), Univ of Massachusetts Press, 1999, pp 105–115.

- Drescher, Seymour, (EAJH) "Jews and the Slave trade", in Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1, Stephen Harlan (Ed.), 1994, page 414-416.

- Drescher, Seymour, (JANCAST) "Jews and New Christians in the Atlantic Slave Trade" in The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1400-1800, Paolo Bernardini (Ed.), 2004, p 439-484.

- Faber, Eli, Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight, New York University Press, 1998.

- Friedman, Saul S. Jews and the American Slave Trade, Transaction, 1999.

- Hastings, James, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Scribners, 1910.

- Graetz, Heinrich, Geschichte der Juden von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart: 11 vols. (History of the Jews; 1853–75), impr. and ext. ed., Leipzig: Leiner; reprinted: 1900, reprint of the edition of last hand (1900): Berlin: arani, 1998, ISBN 3-7605-8673-2. English translation by Philipp Bloch.

- Kritzler, Edwards Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean: How a Generation of Swashbuckling Jews Carved Out an Empire in the New World in Their Quest for Treasure, Religious Freedom—and Revenge, Random House, Inc., 2009.

- Nation of Islam, The Secret relationship between Blacks and Jews, Nation of Islam, 1991

- Raphael, Marc Lee, Jews and Judaism in the United States a Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, Inc., Pub, 1983).

- Roth, Cecil, A history of the marranos, Meridian Books, 1959.

- Schorsch, Jonathan, Jews and blacks in the early modern world, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Wiznitzer, Arnold, Jews in colonial Brazil, Columbia University Press, 1960.