Hegemony: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Niccolo Machiavelli also heavily influenced Gramsci’s writings on hegemony within social classes. According to Gramsci, Machiavelli even “prepared the ground for Marxism by stressing ‘the conformity of means to ends’ in lower classes rising up against the bourgeois.” In Machiavelli’s magnum opus, The Prince, he draws an analogy to a centaur; half-animal, half-man where, “a prince must know how to use both natures, and that one without the other is not durable.” This represents the combination of “coercion and consent” that comprise hegemony, which Gramsci used in articulating tactics and strategy the lower classes could use to confront the bourgeois. Machiavelli also argues that people should determine common goals with each other to transform from an unorganized multitudine sciolta, or multitude of people, into a collective population with organized common goals, populo, using dialogue in a “public space.” Gramsci stipulates that people can become a hegemonic force in a “public space,” or forum to organize as a collective power and approach dealings with the ruling classes with much more leverage. |

Niccolo Machiavelli also heavily influenced Gramsci’s writings on hegemony within social classes. According to Gramsci, Machiavelli even “prepared the ground for Marxism by stressing ‘the conformity of means to ends’ in lower classes rising up against the bourgeois.” In Machiavelli’s magnum opus, The Prince, he draws an analogy to a centaur; half-animal, half-man where, “a prince must know how to use both natures, and that one without the other is not durable.” This represents the combination of “coercion and consent” that comprise hegemony, which Gramsci used in articulating tactics and strategy the lower classes could use to confront the bourgeois. Machiavelli also argues that people should determine common goals with each other to transform from an unorganized multitudine sciolta, or multitude of people, into a collective population with organized common goals, populo, using dialogue in a “public space.” Gramsci stipulates that people can become a hegemonic force in a “public space,” or forum to organize as a collective power and approach dealings with the ruling classes with much more leverage. |

||

==International Relations== |

|||

HEGEMONY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS |

|||

COMPETING THEORIES |

|||

Hegemony, like most theories and assumptions in the field of international relations, does not have one strict definition. Likewise it can be seen and interpreted in a myriad of ways, depending on which theory of international relations one prescribes to. The three major schools of international relations thought, realism, liberalism and constructivism all view hegemony through their own prism. They incorporate their preconceived assumptions and ideas when understanding hegemony. Every school of thought therefore has a slightly different understanding of hegemony, and gives the premise a different worth. |

|||

REALISM |

|||

Realism is one of the foundations on which our understanding of international relations rests. Core assumptions of the realist theory include the premise that states are the principle actors in the international community, and that these states operate in a state of anarchy, with no governing body ruling over them. The main goal of states is to gain power in order to achieve security. For realists, power is best respected when manifested in forms of hard power, most notably military might. Within the format of the global community, according to realists states ought to pursue and balance power. Using these assumptions as the basis for our understanding of realism, one can conclude that realists would inherently be against the principle of hegemony. |

|||

Hegemony would be a direct contradiction to the realist's conception of balance of power. One of the lauded founding philosophers of realist thought, Thucydides, is cited with the passage, "What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta." Here Thucydides describes the rise of a hegemon, in his case it is Athens in the time of antiquity, which disturbed the balance of power and sparked conflict. Richard Nixon, the president of a realist-based foreign policy agenda, reiterates the realist preference for a balance of power and remarked, "the only time in the history of the world that we have had any extended periods of peace is when there has been a balance of power." Thus realists, specifically power balance realists, see war arising due to a movement away from equilibrium. The rise or existence of a hegemon is a threat to the anarchic international system as it moves the system away from equilibrium and is likely to cause instability and conflict. Naturally, as is commonplace in academia and the world of theories, not all realists agree with these power balance assertions. Those realists who do not condemn but rather condone hegemony can be described as power transition realists. |

|||

This contradictory school of realism embraces hegemony as the key to stability and peace in a world of anarchy. They argue that the anarchic system is most stable when one side has a preponderance of power so others dare not attack it. According to this viewpoint a strong hegemon is beneficial to all states within the system as such a state ensures calm, stability and peace. A hegemon creates such stability because a challenger knows that there is no chance of winning a war and the dominant status quo power has no need to resort to war. Referring back to the key assumptions of realism, a states' main objective is security. In this hegemonic equation, both the dominant and the weaker states feel safe since it is in neither party’s interest to wage war. Furthermore, power transition realists assert that the danger of conflict and war arises when the international system transitions away from a hegemon to equilibrium. Such an explanations is oft times used to describe the case of World War I. Great Britain as a hegemony was waning, and the new US hegemony had not yet arisen, and thus in the equilibrium state of international relations, the ground was fertile for conflict as was experience in 1914-1918. |

|||

LIBERALISM |

|||

These contesting perspectives on hegemony signify the deep divisions that run even within a school of thought such as realism. The differences in outlook continue across other schools as well, with schools supporting or opposing hegemony for very different reasons. Liberalism is the second major school of thought. It primarily concerns itself with such qualities as cooperation, with the central concept of liberal ideology being reciprocity. Liberals concern themselves greatly with international régimes, which they believe to be critical in preventing miscommunication and thus conflict. Using this as our foundation for understanding liberalism, we can deduce that liberals, under certain contexts, would not be opposed to hegemony. |

|||

Liberal theoreticians would embrace hegemony due to the fact that it is oftentimes hegemon's who establish and promote international régimes. If it is accepted that the United States was a hegemon post-1945, as John Ikenberry attests in his work Rethinking the Origins of American Hegemony, than the establishment of such international régimes as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trades, the World Trade Organization, and numerous other such entities can be listed as a direct outcome of US hegemony. And since liberals are great proponents of institutions and regimes such as those listed, than by extension they are not entirely opposed to the hegemony, which are often times required to institute them. Thus, if a hegemon is grounded in Western values, democratic principles and promotion of reciprocity, than liberals are in favor, for it is through institutionalization that, according to liberals, conflict is avoided. |

|||

CONSTRUCTIVISM |

|||

Constructivism is the newest of the three schools being analyzed. Whereas the foundation school, realism, rests heavily on assumptions; constructivism places much less emphasis on assumptions. Furthermore, as opposed to realism’s emphasis on hard power, constructivism stresses a combination of both hard but also soft power. Constructivism is a school that highlights the importance of social and cultural contexts. Nye describes the essence of this school of thought, "we need to know who they are, what they want, and how they see the world in order to understand what they do and to know these things we have to understand the social and cultural contexts in which they are embedded." To understand a state, its desires and intentions, it is imperative to first grasp the state's identity, history and peoples. |

|||

Continuing their contrast with realism, constructivists do not place power and the pursuit of power as the central element of the international system. Constructivists "reject the realist view that states must pursue power to ensure their security, pointing out that many states have crafted stable and secure relations that do not rests on calculations of power." In this sense constructivists see hegemony as neither an impediment nor facilitator of global stability. However hegemony would naturally influence stability according to a constructivist. This would be so because constructivists hold that "state identities are complex and changing, and arise from interaction with other states." Certainly a hegemon, being the dominant player in an international community, can influence this interaction, and what the outcome of such interaction was to be -- conflict or peace. |

|||

In essence, the whole premise of hegemony, as understood by realists, does not stand up to constructivist examination, for according to constructivists "nations act not due to anarchy but influence by the prevailing beliefs and norms." If states act according to different goals and premises, than a constructivist international system functions inherently different from a realist one. The entire relationship based on fear and desire for security, as the realists understand it and in which their understanding of hegemony is grounded in, is not accepted entirely by constructivists and therefore constructivist's opinion of hegemony is contradictory to how realists view it. For the realists the presence of hegemony is what either makes or breaks international stability; for a constructivist, hegemony is not the core entity that determines stability; interaction amongst states is. |

|||

ONGOING DEBATE BETWEEN THE COMPETING THEORIES |

|||

Just as hegemony can take different forms and manifestations in the international system, it can also be perceived differently depending on which school of thought one prescribes too. Although hegemony as a theory is most directly linked to realism and its principle of hard power, all three major schools including liberalism and constructivism all view hegemony through their own prism. How each school understands the international system to function and what each school outlines as the goal of international actors will heavily influence how each school views hegemony. Overall, we can clearly state that there is no consensus on the topic of hegemony, and the benefit or harm from the presence of a hegemon is certainly to be debated amongst these schools for years to come. |

|||

HEGEMONIC STABILITY THEORY AND VARYING INTERNATIONAL SYSTEMS |

|||

Much of international relations theory concerns the structure of the international system and how structural factors contribute to the outbreak of violent conflict. As the dominant power in the world or region, hegemons are necessarily a key part of the international system, and have been the focus of considerable study in this vein. Hegemonic stability theory holds that hegemons have a stabilizing effect on the international system and that their downfall or absence increases the likelihood of violent conflict. |

|||

MULTIPOLAR SYSTEMS |

|||

Hegemonic Stability Theory flows out of a debate on the most stable kind of international system—a multi-polar system, a bipolar system, or a unipolar system. Scholars are divided on how stable multi-polar systems tend to be. Karl Deutsch and David Singer use a pluralist model—to argue for the stabilizing effect of a multi-polar system. The model holds that states, like individuals, have numerous identities, and different identities provide different interests. As they explain, “A landlocked nation can hardly offer fishing rights in its coastal waters, an agricultural surplus nation will seldom purchase those same foodstuffs, two underdeveloped nations are most unlikely to exchange machine tools, and a permanent member of the Security Council cannot be expected to give much for assurance of a seat in that organ.” Since the number of possible interactions increases exponentially as the number of actors increases linearly , a multi-polar system rapidly stabilizes as the number of actors increases Furthermore, they argue that as the number of dyads increases, the state must, by necessity, divide its attention to some degree. They assume that the less attention one state pays to another, the less likely it is to initiate a conflict—and that a signal-to-noise ratio of 1:9 (10% attention on average to each country) is the minimum threshold for conflict. |

|||

BIPOLAR SYSTEMS |

|||

Another debate focuses on the stability of bipolar systems. Although they never make the point explicitly, Goldgeier and Tetlock’s argument about signal-to-noise ratio complexity would support the proposition that a bipolar world is more stable than a multi-polar one, since fewer actors means the states in the system are less likely to be swamped with irrelevant information. Kenneth Waltz argues that a bipolar world is inherently stable, although the primary historical case, the Cold War, makes it challenging to sort out whether stability is a function of systemic factors or of the power of nuclear deterrence. Waltz addresses these concerns by arguing that the bipolar system predates the US-USSR nuclear rivalry, that each state could still inflict serious destruction upon the other (similar to, but not as effective as mutually-assured destruction), and that nuclear weapons are the result, not the cause, of great power status. He points to four factors which cause bipolar stability—“the absence of peripheries, the range and intensity of competition, and the persistence of pressure and crisis…combined with a fourth factor, their preponderant power, have made for a remarkable ability to comprehend and absorb within the bipolar balance the revolutionary political, military, and economic changes that have occurred.” Waltz points to the political crises that never escalated into war, the two shifts in China’s allegiance from the US to the USSR and then back to the US, and the proliferation of nuclear technology all without radically altering the balance of power and collapsing the entire system. |

|||

UNIPOLAR SYSTEMS |

|||

Finally, Hegemonic Stability Theory argues that the unipolar world is the most stable of all. John Ikenberry makes a forceful argument in favor of US hegemony through liberal arguments. In a paper prepared for the National Intelligence Council, he argues that American hegemony is unlikely to provoke a balancing of power. He notes that major world powers like the UK, France, Germany, Russia, China, and Japan have made no efforts to collectively balance against US power. Rather, they tend to work either with or around US power without explicitly challenging it. Given the US’s overwhelming power, it is simply infeasible that any coalition could arise to challenge it. Major powers also do not find US power to be threatening. They may still oppose US policies and challenge America, but they do not resort to balancing to overthrow US hegemony. However, Ikenberry notes that the way other countries view America’s exercise of power is consequential, and that those views are influenced by whether the US prefers to exercise power through unilateral, imperialist means, or formal, rule-based institutions. Furthermore, it may be vital to the continued existence of the unipolar order for the US to pursue institutionalized foreign policy in order to allay concerns about its exercise of power from any potential challengers (Ikenberry 3-5) . Whereas realists would argue that a failure of balancing occurs because the power calculations of individual states simply do not favor it, whereas Ikenberry chooses to focus on how power is exercised and how institutions can meaningfully shape perceptions about US foreign policy and the way that other states respond to it. While Ikenberry’s analysis is decidedly focused on the US, the condition of overwhelming power to the point where balancing is infeasible could apply to any hegemon. And while it is not necessary for a future hegemon to utilize international institutions in the execution of its foreign policy, Ikenberry makes a compelling argument for the significance of institutions and the changing face of power in the 21st century. |

|||

Conversely, Nuno Monteiro argues that a unipolar system is in fact highly conflict-prone, although these conflicts usually do not occur between any of the major powers (including the hegemon). Monteiro questions Wohlforth’s assumption that the costs of balancing always exceed the costs of bandwagoning. Monteiro explains that without this assumption, the unipolar system suddenly allows for uncooperative states to exist. He identifies three grand strategies that hegemons will pursue—offensive dominance (a revisionist stance towards existing regional orders), defensive dominance (a status-quo stance towards existing regional orders), and disengagement. Offensive and defensive dominance respectively give the hegemon incentives to fight wars with minor powers to alter or maintain the status quo for its benefit, although this argument contradicts Ikenberry’s argument that the imperialist use of force can intimidate other major powers and even alter their cost-benefit calculations about balancing versus bandwagoning. Disengagement effectively separates a region from the unipolar global system, allowing a unipolar, bipolar, or multi-polar regional system to emerge. While the hegemon is not involved in conflicts in the region it disengages from, major powers within the region are free to fight wars. Monteiro also makes the important claim that if regional disengagement led to a unipolar system, the regional hegemon would then qualify as a true competitor to the global hegemon, ending the unipolar system. |

|||

PSYCHOLOGICAL ELEMENTS OF HEGEMONY |

|||

Scholars such as Goldgeier and Tetlock come to very different conclusions about multi-polarity using psychological explanations. They chose to criticize the rational actor assumptions of realism and instead focus on cognitive psychology. They acknowledge that states have finite information-processing capabilities, and that states have trouble making rational decisions when there is an unfavorable signal-to-noise ratio—the balance of credible political signals and irrelevant information. Multi-polarity increases the quantity and complexity of information a state receives, generally decreasing its ability to effectively process signals. The conclusion is that states in a multi-polar system are much more likely to miscalculate their policy responses, which increases the chance of war . |

|||

William Wohlforth argues more clearly for the stabilizing effect of structural factors of hegemony, although his analysis draws on psychological theories. One of Wohlforth’s key arguments is that just as individuals compete for higher social status, so too do states within the international order—often for domestic political purposes. Wohlforth claims this produces a zero-sum competition, since political status is relative. He argues that the less stratified a system is, the more ambiguous each state’s status is and the more likely they are to engage in competition, where as more stratified unipolar systems offer less incentive for states to fight over the social hierarchy. |

|||

THE ONGOING DEBATE OVER HEGEMONIC STABILITY THEORY |

|||

Each international system—multi-polar, bipolar, and unipolar, has its own stabilizing and destabilizing characteristics. Arguments about multi-polar systems focus on complexity and the ability of semi-rational actors to effectively process all the information necessary to make good policy decisions. This usually translates into conclusions favoring instability, although clearly psychological theories can justify conclusions for either side of the debate. Bipolar systems are generally considered to be stable in the sense that they do not erupt into full-scale great power war, although they are prone to high levels of tension political crises. Finally, hegemonic stability theory argues that competition is not necessary to international stability, and that the emergence of a single, clear hegemon can promote stability, especially if it exercises power through rule-based institutions. Detractors of the theory claim that hegemons generally pursue grand strategies that make them conflict-prone. Even when they choose a more peaceful grand strategy, the normal forces of international anarchy simply re-exert themselves. Scholars have by no means reached a consensus on whether hegemonic stability theory holds credence, but it has nonetheless proved a very attractive theory to debate. |

|||

==Sociology== |

==Sociology== |

||

Revision as of 21:48, 12 December 2012

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Hegemony (UK: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈɡɛməni/, US: /ˈhɛdʒ[invalid input: 'ɨ']moʊni/, US: /h[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈdʒɛməni/; [ἡγεμονία hēgemonía] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), "leadership", "rule") is an indirect form of government of imperial dominance in which the hegemon (leader state) rules geopolitically subordinate states by the implied means of power, the threat of force, rather than by direct military force.[1] In Ancient Greece (8th c. BC – AD 6th c.), hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states.[2] In the 19th century, hegemony denoted the geopolitical and the cultural predominance of one country upon others; from which derived hegemonism, the Great Power politics meant to establish European hegemony upon continental Asia and Africa.[3] In the 20th-century, Antonio Gramsci developed the philosophy and the sociology of geopolitical hegemony into the theory of cultural hegemony, whereby one social class can manipulate the system of values and mores of a society, in order to create and establish a ruling-class Weltanschauung, a worldview that justifies the status quo of bourgeois domination of the other social classes of the society.[2][4][5][6]

In the praxis of hegemony, imperial dominance is established by means of cultural imperialism, whereby the leader state (hegemon) dictates the internal politics and the societal character of the sub-ordinate states that constitute the hegemonic sphere of influence; either by an internal, sponsored government or by an external, installed government. The imposition of the hegemon’s way of life — an imperial lingua franca and bureaucracies (social, economic, educational, governing) — transforms the concrete imperialism of direct military domination into the abstract power of the status quo, indirect imperial domination.[1] Under hegemony, rebellion (social, political, economic, armed) is eliminated either by co-optation of the rebels or by suppression (police and military), without direct intervention by the hegemon; the examples are the latter-stage Spanish and British empires, and the 19th- and 20th-century reichs of unified Germany (1871–1945).[7]

History

- Antiquity

In the Græco–Roman world of 5th-century European Classical antiquity, the city-state of Sparta was the hegemon of the Peloponnesian League (6th – 4th centuries BC) and King Philip II of Macedon was the hegemon of the League of Corinth in 337 BC (a kingship he willed to his son, Alexander the Great). In Ancient Eastern Asia, Chinese hegemony was present during the Spring and Autumn Period (ca. 770–480 BC), when the weakened rule of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty led to the relative autonomy of the Five Hegemons (Ba in Chinese [霸]). They were appointed by feudal lord conferences, and thus were nominally obliged to uphold the imperium of the Zhou Dynasty over the sub-ordinate states. In late-16th– and early-17th-century Japan, the term hegemon applied to its "Three Unifiers" — Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu — who ruled most of the country by hegemony.

The etymological and theoretical underpinnings of hegemony trace back to Ancient Greece. The word hegemony is derived from the Greek word egemonia, meaning “leader, ruler, often in the sense of a state other than his own.” In the context of Ancient Greece, the term “hegemony” is a military-political hierarchy, as opposed to economic or cultural hegemony that emerges as a concept in the late 19th century. For Greeks, a hegemon was a “leader or leading state of a group of societies or states.” Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Ephorus wrote that Sparta and Athens both exhibited behaviors of a hegemon in different periods of their histories. Herodotus observed this influence that Sparta was exercising hegemonic powers and notable influence outside its own territories in organizing a Greek coalition to meet the invasion of Xerxes’ Persian armies in 480 BC. Herodotus noted Athens’ “willingness to give way on its command of the sea,” and put its navy under a Spartan commander, explaining this as “willingness of allies to take orders from the hegemon.” Thucydides said of the same coalition against Xerxes, “while in great peril hung over Greece, the Spartans, being superior in power, were the leaders of the United Greeks.” The Spartans’ superior power actively convinced Athens to accept Spartan rule, as opposed to Athens submitting to Sparta’s will as if they were a conquered territory. Thus, the Ancient Greek interpretation of what constituted a hegemon was not a universal power exerting total control over other actors, but rather a “unipolar influence structure.”

- Middle Ages and Renaissance

As a universal, politico–cultural hegemonic practice, the cultural institutions of the hegemon establish and maintain the political annexation of the subordinate peoples; in Italy, the Medici maintained their medieval Tuscan hegemony, by controlling the production of woolens by controlling the Arte della Lana guild, in the Florentine city-state. In Holland, the Dutch Republic’s 17th-century (1609–1672) mercantilist dominion was a first instance of global, commercial hegemony, made feasible with its technological development of wind power and its Four Great Fleets[citation needed], for the efficient production and delivery of goods and services, which, in turn, made possible its Amsterdam stock market and concomitant dominance of world trade; in France, King Louis XIV (1638–1715) and (Emperor) Napoleon I (1799–1815) established French hegemony via economic, cultural, and military domination of most of Continental Europe. After the defeat and exile of Napoleon, hegemony largely passed to the British Empire, which became the largest empire in world history, with Queen Victoria (1837-1901) ruling over one-quarter of the world's land and population at the zenith of the empire's existence. Like the Dutch, the British Empire was primarily seaborne; many British possessions were located around the rim of the Indian Ocean, as well as numerous islands in the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Britain also controlled large portions of Africa, as well as the entire Indian subcontinent.

- 20th century

The USSR (1922–1991), Nazi Germany (1933–1945), and the USA (1823–present) each sought regional hegemony (sphere of influence), then global hegemony.[8] In 1939, Nazi Germany launched the Second World War (1939–1945) to gain geographic dominance of Eurasia and Africa, initially, by means of empire (direct control), then by hegemony (indirect control). Afterwards, in 1945, the USA and the USSR fought the Cold War (1945–1991) for control of the global European empires of France, Britain, the Netherlands, et al., which were politically destroyed by the global warfare of the Second World War.

The roots of modern concepts of hegemony are founded in influential thinkers including Machiavelli, Marx, Lenin, and perhaps most notably, Antonio Gramsci. While neither Karl Marx nor Vladimir Lenin specifically wrote on the term hegemony, both utilized the concept of hegemony in their writings on the class structure of society. More specifically, Lenin wrote about the “leadership exercised by the proletariat over the other exploited classes.” His 1902 pamphlet, “What is to be done?” on the struggles of the working class cites the concept of gegemoniya, roughly translating to “political predominance, usually of one state over the other.” This concept gained more influence leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Lenin, “advocating strategies mirrored…in concepts of hegemony,” argued that the Bolsheviks had “a bounden duty in the struggle to overthrow autocracy” by “guiding activities” of opposition in tandem with garnering support from urban proletariats. Much like Greek interpretations of hegemony, Lenin’s use of gegemoniya did not connote absolute control over another party, but rather influence and the ability to “guide activities” of another party.

In the mid-20th century, the hegemonic conflict was ideologic, between the Communist Warsaw Pact (1955–1991) and the capitalist NATO (1949-present), wherein each hegemon competed directly (the arms race) and indirectly (proxy wars) against any country whose internal, national politics might destabilise the respective hegemony. The USSR defeated the nationalist Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the USA precipitated the US–Vietnam War (1965–1975) by participating in the Vietnamese Civil War (1955–1965) that the National Liberation Front fought against the Republic of Vietnam, the Asian client state of the United States.[9]

- 21st century

In the post–Cold War (1945–1991) world, the French Socialist politician Hubert Védrine described the USA as a hegemonic hyperpower, because of its unilateral military actions worldwide, especially against Iraq; while the US political scientists John Mearsheimer and Joseph Nye counter that the USA is not a true hegemon because it has neither the financial nor the military resources to impose a proper, formal, global hegemony.[10]

Geography

The Neo-Marxist Henri Lefebvre proposes that geographic space is not a passive locus of social relations, but that it is trialectical — human geography is constituted by mental space, social space, and physical space — hence, hegemony is a spatial process influenced by geopolitics. In the ancient world, hydraulic despotism was established in the fertile river valleys of Egypt, China, and Mesopotamia. In China, during the Warring States Era (476–221 BC), the Qin State created the Chengkuo Canal for geopolitical advantage over its local rivals. In Eurasia, successor state hegemonies were established in the Middle East, using the sea (Greece) and the fringe lands (Persia, Arabia). European hegemony moved westwards, to Rome (27 BC – AD 476/145), then northwards, to the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) of the Franks. Later, at the Atlantic Ocean, Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom established their hegemonic centres.[11]

Political science

In the historical writing of the 19th century, the denotation of hegemony extended to describe the predominance of one country upon other countries; and, by extension, hegemonism denoted the Great Power politics (ca. 1880s–1914) for establishing hegemony (indirect imperial rule), that then leads to a definition of imperialism (direct foreign rule). In the early 20th century, in the field of international relations, the Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci developed the theory of cultural domination (an analysis of economic class) to include social class; hence, the philosophic and sociologic theory of cultural hegemony analysed the social norms that established the social structures (social and economic classes) with which the ruling class establish and exert cultural dominance to impose their Weltanschauung (world view) — justifying the social, political, and economic status quo — as natural, inevitable, and beneficial to every social class, rather than as artificial social constructs beneficial solely to the ruling class.[12][13][14]

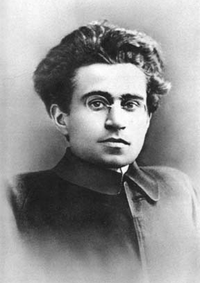

Antonio Gramsci was a communist Italian writer and politician who published influential works on hegemony during the height of Benito Mussolini’s power in Italy in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Gramsci is the theorist “most closely associated with the concept of hegemony,” and hegemony in politics was “somewhat limited until Antonio Gramsci’s intensive discussion of the concept in his political thought.” His most influential works on hegemony were written in his “Prison Notebooks” he wrote while imprisoned by Mussolini’s fascist regime from 1926 to 1934, shortly before his death. Gramsci defined hegemony as “a form of control exercised by a dominant class,” where the hegemonic class is the one “able to attain the consent of other social forces,” and the “retention of this consent is an ongoing project.” In terms of Gramsci’s adherence to Marxist and Leninist communism, this hegemonic class control is a function of economic production of the class. He focused on defining hegemony to both articulate the structures of bourgeois power in 19th and 20th century Europe and to “theorize…the necessary conditions for a successful overthrow of the bourgeoisie by the proletariat and its allies.”

Gramsci’s analysis was not limited to intra-class relations. He also defined hegemony in terms of the state, which later became relevant to scholars of international relations. Gramsci defines the state as “the entire complex of practical and theoretical activities” that the ruling class not only “justifies and maintains its dominance, but manages to win the active consent of those over whom it rules,” similar to how Athens willingly ceding its naval authority to Sparta in the Greek coalition against Xerxes’ invading Persian armies. The primary difference in this analogy is that Herodotus, Thucydides and the other Greek historians saw hegemony through the lens of alliances among states whereas Gramsci sees hegemony as the political interplay within coherent, defined social communities.

From the Gramsci analysis derived the political science denotation of hegemony as leadership; thus, the historical example of Prussia as the militarily and culturally predominant province of the German Empire (Second Reich 1871–1918); and the personal and intellectual predominance of Napoleon Bonaparte upon the French Consulate (1799–1804).[15] Contemporarily, in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe defined hegemony as a political relationship of power wherein a sub-ordinate society (collectivity) perform social tasks that are culturally unnatural and not beneficial to them, but that are in exclusive benefit to the imperial interests of the hegemon, the superior, ordinate power; hegemony is a military, political, and economic relationship that occurs as an articulation within political discourse.[16]

Niccolo Machiavelli also heavily influenced Gramsci’s writings on hegemony within social classes. According to Gramsci, Machiavelli even “prepared the ground for Marxism by stressing ‘the conformity of means to ends’ in lower classes rising up against the bourgeois.” In Machiavelli’s magnum opus, The Prince, he draws an analogy to a centaur; half-animal, half-man where, “a prince must know how to use both natures, and that one without the other is not durable.” This represents the combination of “coercion and consent” that comprise hegemony, which Gramsci used in articulating tactics and strategy the lower classes could use to confront the bourgeois. Machiavelli also argues that people should determine common goals with each other to transform from an unorganized multitudine sciolta, or multitude of people, into a collective population with organized common goals, populo, using dialogue in a “public space.” Gramsci stipulates that people can become a hegemonic force in a “public space,” or forum to organize as a collective power and approach dealings with the ruling classes with much more leverage.

International Relations

HEGEMONY IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS COMPETING THEORIES Hegemony, like most theories and assumptions in the field of international relations, does not have one strict definition. Likewise it can be seen and interpreted in a myriad of ways, depending on which theory of international relations one prescribes to. The three major schools of international relations thought, realism, liberalism and constructivism all view hegemony through their own prism. They incorporate their preconceived assumptions and ideas when understanding hegemony. Every school of thought therefore has a slightly different understanding of hegemony, and gives the premise a different worth. REALISM Realism is one of the foundations on which our understanding of international relations rests. Core assumptions of the realist theory include the premise that states are the principle actors in the international community, and that these states operate in a state of anarchy, with no governing body ruling over them. The main goal of states is to gain power in order to achieve security. For realists, power is best respected when manifested in forms of hard power, most notably military might. Within the format of the global community, according to realists states ought to pursue and balance power. Using these assumptions as the basis for our understanding of realism, one can conclude that realists would inherently be against the principle of hegemony.

Hegemony would be a direct contradiction to the realist's conception of balance of power. One of the lauded founding philosophers of realist thought, Thucydides, is cited with the passage, "What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta." Here Thucydides describes the rise of a hegemon, in his case it is Athens in the time of antiquity, which disturbed the balance of power and sparked conflict. Richard Nixon, the president of a realist-based foreign policy agenda, reiterates the realist preference for a balance of power and remarked, "the only time in the history of the world that we have had any extended periods of peace is when there has been a balance of power." Thus realists, specifically power balance realists, see war arising due to a movement away from equilibrium. The rise or existence of a hegemon is a threat to the anarchic international system as it moves the system away from equilibrium and is likely to cause instability and conflict. Naturally, as is commonplace in academia and the world of theories, not all realists agree with these power balance assertions. Those realists who do not condemn but rather condone hegemony can be described as power transition realists.

This contradictory school of realism embraces hegemony as the key to stability and peace in a world of anarchy. They argue that the anarchic system is most stable when one side has a preponderance of power so others dare not attack it. According to this viewpoint a strong hegemon is beneficial to all states within the system as such a state ensures calm, stability and peace. A hegemon creates such stability because a challenger knows that there is no chance of winning a war and the dominant status quo power has no need to resort to war. Referring back to the key assumptions of realism, a states' main objective is security. In this hegemonic equation, both the dominant and the weaker states feel safe since it is in neither party’s interest to wage war. Furthermore, power transition realists assert that the danger of conflict and war arises when the international system transitions away from a hegemon to equilibrium. Such an explanations is oft times used to describe the case of World War I. Great Britain as a hegemony was waning, and the new US hegemony had not yet arisen, and thus in the equilibrium state of international relations, the ground was fertile for conflict as was experience in 1914-1918. LIBERALISM These contesting perspectives on hegemony signify the deep divisions that run even within a school of thought such as realism. The differences in outlook continue across other schools as well, with schools supporting or opposing hegemony for very different reasons. Liberalism is the second major school of thought. It primarily concerns itself with such qualities as cooperation, with the central concept of liberal ideology being reciprocity. Liberals concern themselves greatly with international régimes, which they believe to be critical in preventing miscommunication and thus conflict. Using this as our foundation for understanding liberalism, we can deduce that liberals, under certain contexts, would not be opposed to hegemony.

Liberal theoreticians would embrace hegemony due to the fact that it is oftentimes hegemon's who establish and promote international régimes. If it is accepted that the United States was a hegemon post-1945, as John Ikenberry attests in his work Rethinking the Origins of American Hegemony, than the establishment of such international régimes as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trades, the World Trade Organization, and numerous other such entities can be listed as a direct outcome of US hegemony. And since liberals are great proponents of institutions and regimes such as those listed, than by extension they are not entirely opposed to the hegemony, which are often times required to institute them. Thus, if a hegemon is grounded in Western values, democratic principles and promotion of reciprocity, than liberals are in favor, for it is through institutionalization that, according to liberals, conflict is avoided. CONSTRUCTIVISM Constructivism is the newest of the three schools being analyzed. Whereas the foundation school, realism, rests heavily on assumptions; constructivism places much less emphasis on assumptions. Furthermore, as opposed to realism’s emphasis on hard power, constructivism stresses a combination of both hard but also soft power. Constructivism is a school that highlights the importance of social and cultural contexts. Nye describes the essence of this school of thought, "we need to know who they are, what they want, and how they see the world in order to understand what they do and to know these things we have to understand the social and cultural contexts in which they are embedded." To understand a state, its desires and intentions, it is imperative to first grasp the state's identity, history and peoples.

Continuing their contrast with realism, constructivists do not place power and the pursuit of power as the central element of the international system. Constructivists "reject the realist view that states must pursue power to ensure their security, pointing out that many states have crafted stable and secure relations that do not rests on calculations of power." In this sense constructivists see hegemony as neither an impediment nor facilitator of global stability. However hegemony would naturally influence stability according to a constructivist. This would be so because constructivists hold that "state identities are complex and changing, and arise from interaction with other states." Certainly a hegemon, being the dominant player in an international community, can influence this interaction, and what the outcome of such interaction was to be -- conflict or peace.

In essence, the whole premise of hegemony, as understood by realists, does not stand up to constructivist examination, for according to constructivists "nations act not due to anarchy but influence by the prevailing beliefs and norms." If states act according to different goals and premises, than a constructivist international system functions inherently different from a realist one. The entire relationship based on fear and desire for security, as the realists understand it and in which their understanding of hegemony is grounded in, is not accepted entirely by constructivists and therefore constructivist's opinion of hegemony is contradictory to how realists view it. For the realists the presence of hegemony is what either makes or breaks international stability; for a constructivist, hegemony is not the core entity that determines stability; interaction amongst states is. ONGOING DEBATE BETWEEN THE COMPETING THEORIES Just as hegemony can take different forms and manifestations in the international system, it can also be perceived differently depending on which school of thought one prescribes too. Although hegemony as a theory is most directly linked to realism and its principle of hard power, all three major schools including liberalism and constructivism all view hegemony through their own prism. How each school understands the international system to function and what each school outlines as the goal of international actors will heavily influence how each school views hegemony. Overall, we can clearly state that there is no consensus on the topic of hegemony, and the benefit or harm from the presence of a hegemon is certainly to be debated amongst these schools for years to come. HEGEMONIC STABILITY THEORY AND VARYING INTERNATIONAL SYSTEMS

Much of international relations theory concerns the structure of the international system and how structural factors contribute to the outbreak of violent conflict. As the dominant power in the world or region, hegemons are necessarily a key part of the international system, and have been the focus of considerable study in this vein. Hegemonic stability theory holds that hegemons have a stabilizing effect on the international system and that their downfall or absence increases the likelihood of violent conflict. MULTIPOLAR SYSTEMS Hegemonic Stability Theory flows out of a debate on the most stable kind of international system—a multi-polar system, a bipolar system, or a unipolar system. Scholars are divided on how stable multi-polar systems tend to be. Karl Deutsch and David Singer use a pluralist model—to argue for the stabilizing effect of a multi-polar system. The model holds that states, like individuals, have numerous identities, and different identities provide different interests. As they explain, “A landlocked nation can hardly offer fishing rights in its coastal waters, an agricultural surplus nation will seldom purchase those same foodstuffs, two underdeveloped nations are most unlikely to exchange machine tools, and a permanent member of the Security Council cannot be expected to give much for assurance of a seat in that organ.” Since the number of possible interactions increases exponentially as the number of actors increases linearly , a multi-polar system rapidly stabilizes as the number of actors increases Furthermore, they argue that as the number of dyads increases, the state must, by necessity, divide its attention to some degree. They assume that the less attention one state pays to another, the less likely it is to initiate a conflict—and that a signal-to-noise ratio of 1:9 (10% attention on average to each country) is the minimum threshold for conflict. BIPOLAR SYSTEMS Another debate focuses on the stability of bipolar systems. Although they never make the point explicitly, Goldgeier and Tetlock’s argument about signal-to-noise ratio complexity would support the proposition that a bipolar world is more stable than a multi-polar one, since fewer actors means the states in the system are less likely to be swamped with irrelevant information. Kenneth Waltz argues that a bipolar world is inherently stable, although the primary historical case, the Cold War, makes it challenging to sort out whether stability is a function of systemic factors or of the power of nuclear deterrence. Waltz addresses these concerns by arguing that the bipolar system predates the US-USSR nuclear rivalry, that each state could still inflict serious destruction upon the other (similar to, but not as effective as mutually-assured destruction), and that nuclear weapons are the result, not the cause, of great power status. He points to four factors which cause bipolar stability—“the absence of peripheries, the range and intensity of competition, and the persistence of pressure and crisis…combined with a fourth factor, their preponderant power, have made for a remarkable ability to comprehend and absorb within the bipolar balance the revolutionary political, military, and economic changes that have occurred.” Waltz points to the political crises that never escalated into war, the two shifts in China’s allegiance from the US to the USSR and then back to the US, and the proliferation of nuclear technology all without radically altering the balance of power and collapsing the entire system.

UNIPOLAR SYSTEMS Finally, Hegemonic Stability Theory argues that the unipolar world is the most stable of all. John Ikenberry makes a forceful argument in favor of US hegemony through liberal arguments. In a paper prepared for the National Intelligence Council, he argues that American hegemony is unlikely to provoke a balancing of power. He notes that major world powers like the UK, France, Germany, Russia, China, and Japan have made no efforts to collectively balance against US power. Rather, they tend to work either with or around US power without explicitly challenging it. Given the US’s overwhelming power, it is simply infeasible that any coalition could arise to challenge it. Major powers also do not find US power to be threatening. They may still oppose US policies and challenge America, but they do not resort to balancing to overthrow US hegemony. However, Ikenberry notes that the way other countries view America’s exercise of power is consequential, and that those views are influenced by whether the US prefers to exercise power through unilateral, imperialist means, or formal, rule-based institutions. Furthermore, it may be vital to the continued existence of the unipolar order for the US to pursue institutionalized foreign policy in order to allay concerns about its exercise of power from any potential challengers (Ikenberry 3-5) . Whereas realists would argue that a failure of balancing occurs because the power calculations of individual states simply do not favor it, whereas Ikenberry chooses to focus on how power is exercised and how institutions can meaningfully shape perceptions about US foreign policy and the way that other states respond to it. While Ikenberry’s analysis is decidedly focused on the US, the condition of overwhelming power to the point where balancing is infeasible could apply to any hegemon. And while it is not necessary for a future hegemon to utilize international institutions in the execution of its foreign policy, Ikenberry makes a compelling argument for the significance of institutions and the changing face of power in the 21st century.

Conversely, Nuno Monteiro argues that a unipolar system is in fact highly conflict-prone, although these conflicts usually do not occur between any of the major powers (including the hegemon). Monteiro questions Wohlforth’s assumption that the costs of balancing always exceed the costs of bandwagoning. Monteiro explains that without this assumption, the unipolar system suddenly allows for uncooperative states to exist. He identifies three grand strategies that hegemons will pursue—offensive dominance (a revisionist stance towards existing regional orders), defensive dominance (a status-quo stance towards existing regional orders), and disengagement. Offensive and defensive dominance respectively give the hegemon incentives to fight wars with minor powers to alter or maintain the status quo for its benefit, although this argument contradicts Ikenberry’s argument that the imperialist use of force can intimidate other major powers and even alter their cost-benefit calculations about balancing versus bandwagoning. Disengagement effectively separates a region from the unipolar global system, allowing a unipolar, bipolar, or multi-polar regional system to emerge. While the hegemon is not involved in conflicts in the region it disengages from, major powers within the region are free to fight wars. Monteiro also makes the important claim that if regional disengagement led to a unipolar system, the regional hegemon would then qualify as a true competitor to the global hegemon, ending the unipolar system.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ELEMENTS OF HEGEMONY Scholars such as Goldgeier and Tetlock come to very different conclusions about multi-polarity using psychological explanations. They chose to criticize the rational actor assumptions of realism and instead focus on cognitive psychology. They acknowledge that states have finite information-processing capabilities, and that states have trouble making rational decisions when there is an unfavorable signal-to-noise ratio—the balance of credible political signals and irrelevant information. Multi-polarity increases the quantity and complexity of information a state receives, generally decreasing its ability to effectively process signals. The conclusion is that states in a multi-polar system are much more likely to miscalculate their policy responses, which increases the chance of war .

William Wohlforth argues more clearly for the stabilizing effect of structural factors of hegemony, although his analysis draws on psychological theories. One of Wohlforth’s key arguments is that just as individuals compete for higher social status, so too do states within the international order—often for domestic political purposes. Wohlforth claims this produces a zero-sum competition, since political status is relative. He argues that the less stratified a system is, the more ambiguous each state’s status is and the more likely they are to engage in competition, where as more stratified unipolar systems offer less incentive for states to fight over the social hierarchy.

THE ONGOING DEBATE OVER HEGEMONIC STABILITY THEORY

Each international system—multi-polar, bipolar, and unipolar, has its own stabilizing and destabilizing characteristics. Arguments about multi-polar systems focus on complexity and the ability of semi-rational actors to effectively process all the information necessary to make good policy decisions. This usually translates into conclusions favoring instability, although clearly psychological theories can justify conclusions for either side of the debate. Bipolar systems are generally considered to be stable in the sense that they do not erupt into full-scale great power war, although they are prone to high levels of tension political crises. Finally, hegemonic stability theory argues that competition is not necessary to international stability, and that the emergence of a single, clear hegemon can promote stability, especially if it exercises power through rule-based institutions. Detractors of the theory claim that hegemons generally pursue grand strategies that make them conflict-prone. Even when they choose a more peaceful grand strategy, the normal forces of international anarchy simply re-exert themselves. Scholars have by no means reached a consensus on whether hegemonic stability theory holds credence, but it has nonetheless proved a very attractive theory to debate.

Sociology

Culturally, hegemony also is established by means of language, specifically the imposed lingua franca of the hegemon (leader state), which then is the official source of information for the people of the society of the sub-ordinate state. Therefore, in the selection of the particular information to be communicated to the sub-ordinate populace, the language of the hegemon thus limits what is communicated; hence, the source practises hegemonic influence upon the person or people receiving the given information. In contemporary society, the exemplar hegemonic organisations are churches and the mass communications media that continually transmit data and information to the public. As such, the ideologic content of the data and information are determined by the vocabulary with which the messages are presented — how the messages are presented; thereby determines the value of the information as "reliable" or "unreliable", as "true" or "false", for the recipient reader, listener, and viewer. Hence is language essential to the imposition, establishment, and functioning of the cultural hegemony that influences what and how people think about the status quo of their society. [citation needed]

See also

- 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état

- Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916), by Lenin

- Balance of power

- Cultural hegemony

- Dominant ideology

- Hegemonic masculinity

- Hyperpower

- Monetary hegemony

- Post-hegemony

- Regional hegemony

- Soft power

- Chantal Mouffe

- Edward Soja

- David Harvey

- Noam Chomsky

References

- ^ a b Ross Hassig, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest (1994), pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1994) p. 1215.

- ^ Alan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, eds. The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999) pp. 387–388.

- ^ Clive Upton, William A. Kretzschmar, Rafal Konopka: Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English. Oxford University Press (2001)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ US Hegemony

- ^ Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (1984), pp. 137-138: "European coalitions were likely to arise to contain Germany's Nazis growing, potentially dominant, power"; p.145: "Unified Germany was achieving the strength to dominate Europe all by itself — an occurrence which Great Britain had always resisted in the past when it came about by conquest".

- ^ Christopher Hitchens Why Orwell Matters (2002) pp. 86–87.

- ^ George C. Kohn Dictionary of Wars (1986) p.496

- ^ Joseph S. Nye Sr., Understanding International Conflicts: An introduction to Theory and History, pp. 276-277

- ^ Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (1992)

- ^ Alan Bullock and Stephen Trombley, eds., The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Third Edition (1999) pp. 387–388

- ^ K. J. Holsti, The Dividing Discipline: Hegemony and Diversity in International Theory (1985).

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. (1994) p. 1215

- ^ Chris Cook, Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983) p. 142.

- ^ Ernest Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, Second Edition. (2001) pp. 40-59, 125-144.

Further reading

- DuBois, T. D. (2005). "Hegemony, Imperialism and the Construction of Religion in East and Southeast Asia." History & Theory, 44, 4, 113-131.

- Hopper, P. (2007). Understanding Cultural Globalization. 1st ed. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

- Howson, Richard, ed. (2008). Hegemony: studies in consensus and coercion. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-95544-7.

- Joseph, Jonathan (2002). Hegemony: A Realist Analysis. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26836-2.

- Slack, Jennifer Daryl (1996). "The Theory and Method of Articulation in Cultural Studies". Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Routledge. pp. 112–127.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)